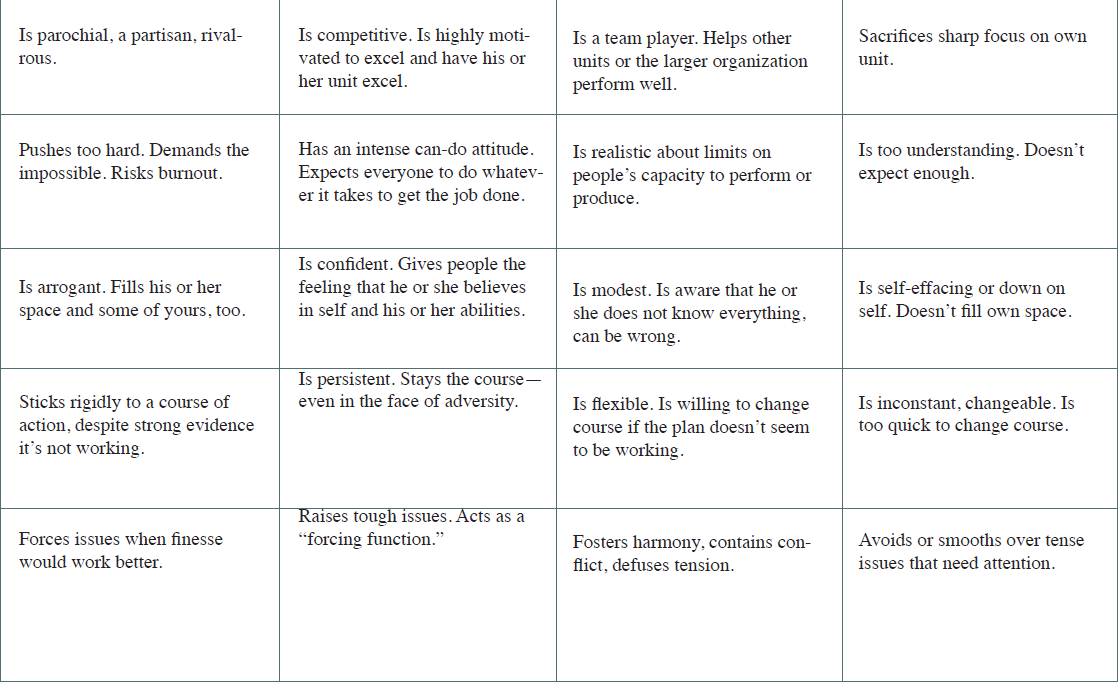

Development Needs as Lack of Versatility

If we accept the premise that each side of the forceful-enabling polarity is a virtue, then we have a way of understanding how senior managers develop performance problems. They do so by taking one of the two approaches to an extreme (Table 2, pp. 14-15). It occurred to me in working with an executive a couple of years ago that he, like so many of his peers, was, as the saying goes, a force to be reckoned with. And how did he get into trouble? By being too much of a force. The same thing applies to the enabling side. As one senior leader said in reference to a talented, highly effective, but distinctly unversatile executive who reports to him, “There is nothing in the world that is purely good.”

In my work I often hear people say, “That’s a weakness tied to a strength,” meaning that the weakness is actually a byproduct of something the individual does well. Let’s see how this applies to a series of specific pairs of forceful-enabling behaviors.

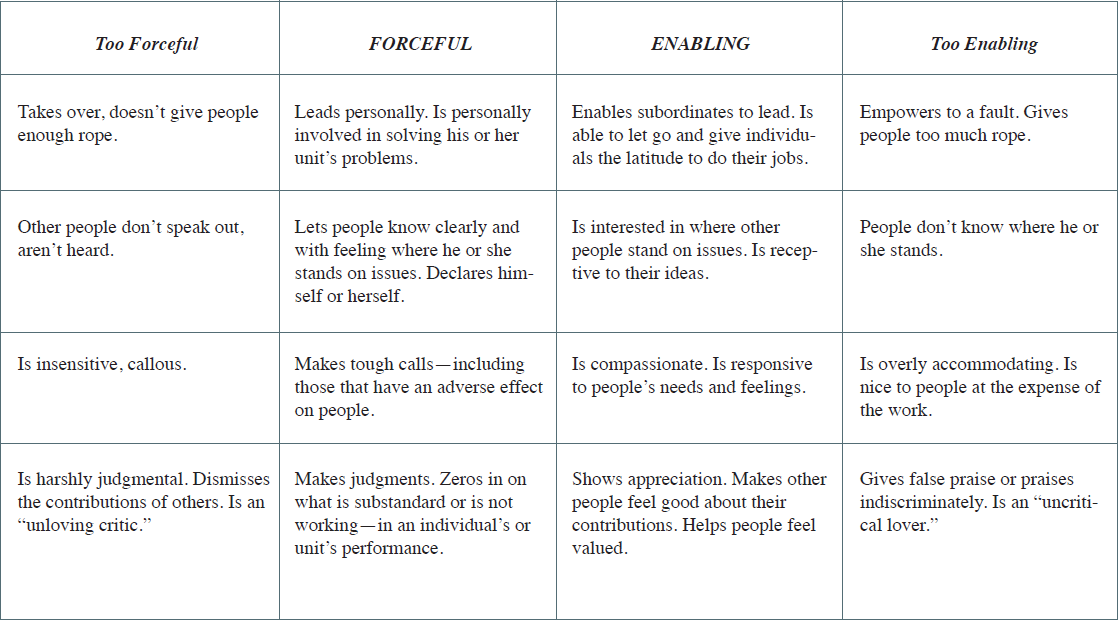

Getting involved personally versus granting autonomy. It is important, on the forceful side, that senior leaders, at least on certain high-priority issues in their units, assert themselves personally and get directly involved in resolving those issues. Leaders must be capable of taking full control and leading personally. On the enabling side, executives must empower their subordinates, must make it possible for them to lead, and must give them the autonomy they want and need to do their jobs. Is one of these functions more important than the other? Doubtful. Both are needed.

If leading personally and getting personally involved in solving a unit’s problems is a virtue, it is also true that doing that to an extreme, taking over completely and depriving subordinates of autonomy, is a vice. Conversely, if affording subordinates sufficient latitude is a virtue, then it is also true that overdoing that, giving people too much autonomy, is a vice. What is interesting is that leaders who excel at taking charge tend not to do as well at letting go, and vice versa.

Declaring oneself versus hearing from other people. On the forceful side, leaders need to let people know clearly and with feeling where they stand. They must declare themselves. On the enabling side, leaders need to take a genuine interest in where other people stand on issues. Leaders must be receptive to the ideas of others in order to benefit from those ideas.

Either of these taken to an extreme creates problems. As important as declaring oneself can be, the leader should not deprive other people of the chance to speak on issues. On the other hand, although it is necessary to take a genuine interest in where other people stand on issues, the leader must let others know where he or she stands. Leaders who know their own minds and speak out easily tend to have trouble being receptive and solicitous of other people’s thoughts, and vice versa.

Making tough calls versus being sensitive to people’s needs. Another familiar pairing, which Morgan McCall, Michael Lombardo, and Ann Morrison (1988, p. 144) identified as a tension needing management, is the need to be tough versus compassionate. On the one hand, leaders are called upon to make tough calls—for example, laying people off or killing a long-term project that is unlikely to pay off. Tough is defined as making decisions that run counter to the needs of the people involved, that take away something, that hurt people. Making tough calls requires a resolve. On the other hand, leaders need to be compassionate, meaning they must be responsive to the plight of individuals—to a crisis in a subordinate’s life or to the stresses and strains that occur on the job.

Table 2

Forceful Leadership and Enabling Leadership: Virtues and Vices

If making tough calls, even when they have an adverse effect on people, is a virtue, then taking that to an extreme, where the leader becomes callous and insensitive to people’s needs, is a vice. In the same way, compassion becomes a vice if being accommodating to people takes precedence over the work. Executives with a proven ability to take tough action—in turnaround situations, for example—often lack sensitivity, and those executives who have ample “people-sensitivity” tend to have trouble being tough—for example, in removing poor performers.

Making critical judgments versus showing appreciation. Although the capacity to make judgments and identify deficiencies in an individual’s or unit’s performance is a great asset, doing that exclusively becomes a liability. A critical approach can degenerate into one that is harshly judgmental and even dismissive of the contributions of others. Likewise, if a capacity to show appreciation for a job well done is an asset, then showering praise on people indiscriminately and even falsely is certainly a liability. Executives who possess a well-developed critical faculty are not usually known for praising people, and executives who are more appreciative and positively reinforcing may have a hard time criticizing a subordinate’s performance directly.

Having a can-do attitude versus accepting limits. On the forceful side, there is no doubt that an intense can-do attitude is indispensable to executives if they are to inspire others to high performance. The risk is that this attitude will be pushed to the point where the leader perpetually demands too much, pushes others too hard, and runs the risk of burnout. On the enabling side, leaders need to be realistic about the limits on human performance and endurance so that the organization can preserve its most precious asset, its capability. Yet the understanding leader runs the risk of settling for too little. Leaders who are admirably attentive to their subordinates’ need for balance in their lives, and who are careful about not intruding on family time, sometimes unduly limit the accomplishments of their organizations.

Conveying confidence versus showing modesty, humility. We certainly want our senior leaders to be confident; their faith in themselves can rub off on the rest of the organization. Taken too far, however, confidence becomes arrogance, which only gets in the way. On the other hand, a certain modesty in senior leaders is disarming, especially when it is accompanied by high achievement. Yet, when taken too far, that otherwise desirable quality becomes self-doubt that can have a depressive effect on others. One senior executive I know of had a habit of blurting out his worries to large groups of employees, who had trouble putting such confessional statements into perspective.

These several pairs constitute only a sample of the managerial behaviors that can be seen in terms of forceful and enabling. In addition to playing out in relationships with subordiantes and with peers, the forceful-enabling distinction can also apply to relationships with superiors. A leader who is upwardly forceful is able to disagree with, or push back on, superiors. In the extreme case, however, the subordinate challenges the superior about virtually everything and becomes difficult to manage. Conversely, a leader who is upwardly enabling is responsive to the requests or initiatives of superiors but in extreme cases lacks the ability to speak out when required.

Lopsidedness or Restricted Movement

In general, for any given pair of opposing characteristics such as those described above, there is a tendency for executives to be strong on one side, and liable to take that to an extreme, while at the same time being relatively weak on the other side. Thus, we have a situation, which I refer to as lopsided,1 where one side is overweighted and the other side is underweighted. A lopsided manager places greater weight or emphasis on one side of the forceful-enabling polarity and less weight on the other.

This typically describes a development need. In these terms development is defined as moving toward a weighting that is more even. An important lesson here is that the two sides are intimately bound up, so that to become less extreme on the overweighted side virtually requires that the individual place more weight on the other side. And, conversely, for an individual to address a development need consisting of an underdeveloped aspect virtually requires that some weight be taken off the opposing side.

Managers are usually evaluated against lists of criteria. Sometimes it’s a company-generated list of leadership attributes, and sometimes it’s a 360-degree instrument developed by outside specialists. (For samples of lists from the academic world and the corporate world, see the Appendix.)

In order to emphasize versatility, it can be useful to think about leadership attributes as pairs of opposites. The typical, unpaired list does not do as good a job of bringing out the need for versatility. The two dimensions tough and compassionate or their equivalent, for example, make it onto many lists of managerial characteristics. If we juxtapose the two, because managers are often high on one and low and the other—very tough and not very compassionate, or the reverse—we can easily see the relationship between the two attributes. In addition to how one does on each characteristic, a manager can be evaluated on how he or she does on the pair.

Another way to think about the need for versatility is in terms of freedom of movement. From this perspective, lack of versatility is restricted range of movement. Managers who lack versatility can’t turn as freely to one side as to the other. To repeat the analogy of the swivel chair, they can turn one way but their movement in the other direction is restricted. As a result these managers not only spend less time looking toward the restricted direction, they spend more time in the area where they can move freely. Also, by looking primarily one way, they may leave themselves exposed on the other side and run the risk of being blindsided.

Whether we think of lack of versatility as lopsideness or as restricted range of movement, the important point is that performance problems show up in two ways: Managers don’t merely underdo one of the approaches; they overdo the other.

Let’s look at how this plays out on the job. What follows are two case studies, each based on the experience of several executives I have studied. A caution: Most executives are not as extreme as those in these cases.

Case of Overly Forceful, Not Enabling Enough

Let’s call the first executive Glen Herroh. In his early forties, he had already reached a high position with his company because of the strength of his obvious talent and impressive business accomplishments. Glen’s leadership was distinguished most of all by his personal efficacy and power. He had developed his innate intellectual gifts to a high degree. He was intensely, even fiercely, task-oriented, the sort of leader who would lock on an objective and not back off until that objective was achieved, however many months or years later, however many obstacles. Glen took great personal satisfaction in using his talents—in studying a complex business situation and coming up with a stretch objective, in leading a discussion of an operating problem, in using the questioning, Socratic method to test the logic of a direct report.

Glen fairly reveled in his efficacy and operated from the “hero model” (Hitt, 1988). Such leaders derive great satisfaction from personally saving the day and prevailing against heavy odds. Glen once explained to me that “self-actualization comes from the impossible dream achieved.”

Without revealing the exact details of Glen’s upbringing, let us simply say that he was born into difficult circumstances in which he felt wronged. It could have been race, religion, or ethnic background. It could also have been the way he was treated by his parents. Some individuals succumb to adversity. Glen reacted by making it his lifelong ambition to prevail in this world. Although his ambition lapsed for several years starting in junior high school, and it was only after he almost flunked out of college that he “snapped out of it,” Glen used his sense of being “one-down” to fuel his rise. Note that, although this is characteristic of several senior people I have worked with, this is not the only childhood antecedent of forceful leadership.

A major criticism of Glen, despite his talents and accomplishments, was that he did not make the best use of the talents and contributions of other people. As smart and quick-witted as he was, he was impatient with people who didn’t “get it” right away. In fact, he was capable from time to time of being abusive, if anything important went wrong or a subordinate failed to do something the way Glen thought it should be done. His preference for Socratic discussions in the round followed the “hub and spoke” model. Most of the action and interaction occurred between him and one or another of his subordinates, and comparatively little interaction took place among subordinates. In other words, the “rim of the wheel” was underdeveloped. In general, he did a lot of the talking in conversations and meetings and, therefore, made it difficult for other people to contribute. One of his people offered this analogy:

Being in a meeting with you is like playing Jeopardy. I’ve got my finger on the buzzer, but you always hit the buzzer first. So I never get to feel smart. If I had another second or two, I’d come up with the right answer, but I never get the chance. We all know that you’re smarter than us, but that doesn’t need to be proven. If you let people have a chance, the organization could develop more confidence.

A co-worker used this imagery to capture the connection between Glen’s considerable talent and his limitation in taking full advantage of the talents of others:

Glen is extraordinarily capable—talented to the max. But he could do less and be more effective if he would let those that he works with work with him. [Note the use of the word let, meaning “enable.”] He is a shining star. He’s a nova. But there are some other stars in the galaxy that he could work with in a really nice harmony.

The extent to which Glen Herroh was heavily weighted on the forceful side and underweighted on the enabling side was clearly manifested on the Executive Roles Questionnaire that I have developed with some colleagues. Twelve of Glen’s co-workers rated him on the several dimensions of forceful leadership listed in Table 1. (These ratings are not composite but are the actual results of one of the eight executives on whom this case is based.) On all but one of the forceful dimensions he was rated as being too forceful. On all but two of the enabling dimensions he was rated as not being enabling enough. To see most clearly the seesaw effect, I did a simple count of the number of times his co-workers rated him too forceful or not forceful enough and too enabling or not enabling enough. As Table 3 shows, his total score on too forceful was 46; on not forceful enough, 2. His total score on not enabling enough was 65; on too enabling, 0.

Table 3

Glen Herroh’s Leadership (on the Executive Roles Questionnaire)

Enabling |

Forceful |

|

Too much |

0 |

46 |

Too little |

65 |

2 |

Case of Overly Enabling, Not Forceful Enough

One of the things that impressed people the most about the executive I will call Bill Borden was how well he listened. He was truly receptive to other people’s ideas. He wasn’t just interested; he was understanding. He had a capacity for putting himself in the place of others. He did more than just take in what people said; he generally let them run with their ideas and act on them without him looking over their shoulders. Bill was a constructive, considerate person. He treated people well. All in all, he was a distinctly positive people leader, a classic enabling executive who listened, empowered, encouraged, recognized, and coached. He had a lot of ego, but it did not get in the way. He prided himself on being a team player who took his place as the head of his organization but also joined the team he led. He had been successful in a series of challenging jobs, and this was in no small measure because his enabling style had won him enthusiastic followers. Because of his admirable personal qualities, which included a high level of integrity and a strong sense of fair play, he was widely trusted and popular. Many people felt good about Bill Borden as a person.

His performance problems were a function of taking some of these strengths to an extreme. He was criticized for “empowering to a fault,” meaning that he turned over too much responsibility and was not enough of a force himself. This was clearly apparent on the Executive Roles Questionnaire, where all eight respondents indicated that he was not personally involved enough in solving his unit’s problems; four of the eight indicated that he enabled his subordinates too much.

In giving his people plenty of responsibility, Bill did not demand enough of them, did not clearly express his expectations, and did not express his dissatisfaction strongly enough when they failed to meet his expectations. He was understanding to the point of being too understanding, too tolerant. As a colleague told him in one of the discussions that followed a feedback session:

You choose to live with situations that aren’t working, and you’re tolerant of people who are terrible! You could fight for people who would do a better job and who would make your life better. You let X choose between two jobs when you know that he would do better in one of those jobs.

Bill had trouble imagining putting his foot down in such a case. Why? “Fear of offending,” Bill said.

He was also criticized for not being decisive enough when it came to making the tough calls. This is where his popularity, or more accurately his need to be popular, hurt him. On the Executive Roles Questionnaire, six of eight co-workers rated him as not decisive enough.

A related fault, especially in the eyes of top management, was that he did not drive change as hard as he should. Several members of the top group worried that his sense of urgency needed to be stronger. One top executive complained that he was “too reasonable.” Overall, they were not sure he was sufficiently tough to make the dramatic changes his unit required. On the Executive Roles Questionnaire, seven of eight people reported he did not make enough tough calls; six of eight said that he was too concerned with fostering harmony.

The last major concern was that his people did not know clearly enough where he stood strategically. Of course his unit had a strategy, at least for the near to midterm, but it seemed to his team that the strategy was essentially a group product and that they did not really know what Bill believed. The strategy was, in a sense, a coauthored document. It was as if his voice were lost, or at least muted, in his collective process of leadership. This showed up clearly on the Executive Roles Questionnaire; all eight co-workers indicated that he didn’t declare himself enough, and four of eight indicated that he was too receptive to other people’s ideas.

In summary, Bill Borden was a clear case of an overly enabling leader. Summing across the nine dimensions of forceful leadership on the Executive Roles Questionnaire, you find that his score on too little was 49 and on too much was 3. Across the nine dimensions of enabling leadership, his score was 7 on too little and 29 on too much (Table 4).

Table 4

Bill Borden’s Leadership (on the Executive Roles Questionnaire)

Enabling |

Forceful |

|

Too much |

29 |

3 |

Too little |

7 |

49 |

A clue about what went into creating this lopsided pattern came from information we gathered about Bill’s childhood. He received very strong messages from his parents to be a winner but to stay humble: “Don’t win at someone’s expense,” “Don’t run up the score,” “Be a good sport,” “Play by the rules,” “It’s the team that wins,” “Help your teammates out,” “It’s not important to be the star.” These parental restraints probably account for some of his reluctance to act forcefully and the inhibition he felt on his power.

1 Originally the word lopsided applied to ships. A lopsided ship leans toward starboard or port because it is heavier on one side.