4

Cash Receipt Schemes and Other Asset Misappropriations

The Fraud Tree, as shown on page 8, was developed as a classification system to identify occupational frauds and abuses by the methods used to commit them. By categorizing schemes into different classifications, antifraud professionals can identify common methods used by perpetrators and typical vulnerabilities in victim organizations that allow these schemes to succeed.

In this chapter, the authors will examine the theft of cash as it enters the business, as well as the theft of noncash assets. Those modules, along with the learning objectives, include the following:

- Module 1 examines cash skimming, whereby the fraudster absconds with cash as it enters the business and before it is entered into the company’s books. The objective is for the reader to be able to describe cash skimming, as well as discuss how cash sales skimming is committed and concealed.

- Module 2 reviews accounts receivable skimming. This fraud scheme is more complicated because cash is usually received in the form of checks. Further, because the organization has a receivable on the books, concealment is more complicated. The goal in this module is for the reader to identify antifraud measures regarding receivables, and apply them to specific case scenarios.

- Module 3 takes a look at cash larceny; this scheme is often thought of as a pure cash grab. However, concealment of the cash theft is an integral part of the fraud scheme. The goal here is for the reader to describe the activities and concealment efforts associated with cash larceny.

- Module 4 reviews noncash asset misappropriation schemes, including asset misuse, unconcealed larceny, asset requisitions and transfers, purchasing and receiving schemes and fraudulent shipments. The take-away from module 4 will be the reader’s ability to adjust the application of antifraud methodology to case issues when cash is not the target of the fraudster’s efforts.

- Module 5 offers a deeper look at inventory issues. Inventory is a significant asset, and noncash asset misappropriation schemes often result in inventory shrinkage that exceeds normal levels associated with breakage, third-party theft, and other typical causes of inventory shortages. The important goal here is for the reader to recognize that inventory shrinkage should be considered as a possible red flag of fraud.

- Module 6 looks more carefully at fraudulent documentation used to conceal noncash misappropriation of assets. The objective is for the reader to recognize concealment efforts that utilize fraudulent support and consider data analytic tools and techniques to detect suspicious anomalies.

Module 1: Skimming Schemes—Cash

Skimming is the theft of cash from a victim entity prior to entry in an accounting system. Because the cash is stolen before it has been recorded in the victim company’s books, skimming schemes are known as “off-book” frauds, and, because the missing money is never recorded, skimming schemes leave no direct audit trail. Consequently, it may be difficult to detect that the money has been stolen. This is the principal advantage to the fraudster of a skimming scheme.

Skimming can occur at any point where funds enter a business; so almost anyone, who receives cash or a cash equivalent—checks, money orders, bank checks—in a business, may be in a position to skim money. This includes salespeople, tellers, wait staff, and others who receive cash directly from customers. In addition, employees whose duties include receiving and logging payments made by customers through the mail may perpetrate skimming schemes. These employees are able to slip checks out of the incoming mail for their own use, rather than posting the checks to the proper revenue or customer accounts. Those who deal directly with customers, or who handle customer payments, are obviously the most likely candidates to skim funds.

How might a person steal checks payable to his employer? Let’s assume that Office Supplies Inc., LLC. is his employer’s company name.

- Step 1: The fraud perpetrator files documents with the Secretary of State’s office to create a new company called OSI, LLC, an abbreviation for Office Supplies Inc., LLC.

- Step 2: Armed with the Secretary of State documents for the new company, the perpetrator can apply for a federal tax identification number.

- Step 3: With both the Secretary of State papers and the federal tax identification number, the perpetrator can now open a bank account for OSI, LLC.

- Step 4: Perpetrating the fraud: When checks arrive made out to Office Supplies Inc., LLC, the perpetrator skims the occasional check and deposits it into OSI, LLC’s bank account. It’s not uncommon for companies such as Office Supplies Incorporated, to have a corporate entity with a different name. Once this pattern has been established with the bank, the fraud can progress.

- Step 5: Concealing the fraud: The perpetrator manages the accounts receivable from Office Supplies Inc., LLC associated with the missing checks through techniques outlined later in this chapter.

Skimming schemes often follow the basic pattern as shown in Figure 4-1: An employee steals incoming funds before they are recorded in the victim organization’s books. Within this broad category, skimming schemes can be subdivided based on whether they target sales or receivables. The character of the incoming funds has an effect on how the frauds are concealed, and concealment is crucial to occupational fraud schemes.

FIGURE 4-1 Unrecorded sale

Sales Skimming

The most basic skimming scheme occurs when an employee makes a sale of goods or services to a customer, collects the customer’s payment at the point of sale, but makes no record of the transaction. The employee pockets the money received from the customer, instead of turning it over to his employer.

In order to discuss sales skimming schemes more completely, let us consider one of the simplest and most common sales transactions, a sale of goods at the cash register.

In a normal sale transaction, a customer purchases an item—such as a pair of shoes—and an employee enters the sale into the cash register. The register tape reflects that the sale has been made and shows that a certain amount of cash (the purchase price of the item) should have been placed in the register. By comparing the register tape to the amount of money on hand, differences in the amounts may indicate thefts. For instance, if $500 in sales is recorded on a particular register, but only $400 cash related to those sales is counted in the register, reasons for the discrepancy of $100 must be provided (this example assumes a zero beginning cash balance).

When an employee skims money by making off-book sales of merchandise, however, the theft cannot be detected by comparing the register tape to the cash drawer because the sale was never recorded on the register. Return to the example in the preceding paragraph.

Assume a fraudster wants to steal $100, and there are $500 of sales at that employee’s cash register throughout the course of the day. Also assume one sale involves a $100 pair of shoes. When the $100 sale is made, the employee does not record the transaction on his register. The customer pays $100 and takes the shoes home, but instead of placing $100 in the cash drawer, the employee pockets it. Because the employee did not record the sale, at the end of the day, the register tape reflects only $400 in sales. There will be $400 in the register ($500 in total sales minus the $100 that the employee stole), so the register tape and cash on hand amounts match. By not recording the sale, the employee was able to steal money without the missing funds raising any red flags.

A typical control is for retailers to require that customers must receive a receipt. A sign behind the counter of a fast food restaurant informed customers that they would receive a free meal if they alerted the manager that they did not receive a sales receipt. This was more than the company’s attempt to offer good service, it was also an antifraud tool to prevent cash skimming.

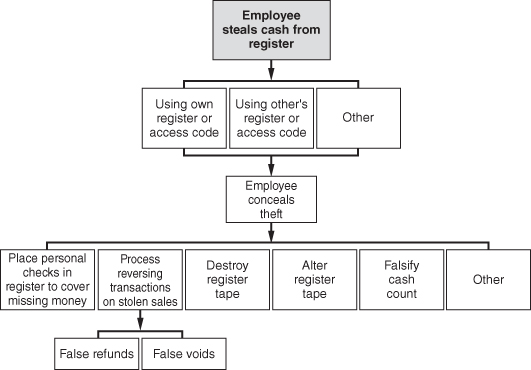

Cash Register Manipulation

One of the most difficult parts of a skimming scheme at the cash register is the overt act of taking the money. If the employee takes the customer’s money and puts it in his pocket without entering the transaction on the register, the customer may suspect that something is wrong and report the conduct to another employee or a manager. It is also possible that a manager, a fellow employee, or a surveillance camera will spot the illegal conduct.

To conceal theft, an employee might ring a “no sale” or other noncash transaction on the register. The fraudulent transaction is entered so that it looks like a sale is being recorded when in fact the employee is stealing the customer’s payment. To the casual observer, it appears as though the sale is being properly recorded.

In other cases, employees rigged their cash registers so that sales are not printed on the register tapes. With modern cash registers, this is difficult to do. As the authors stated, the amount of cash on hand in a register may be compared to the amount showing on the register tape to detect employee theft. It is therefore not important to the fraudster what is keyed into the register, but rather what shows on the tape. If employees can rig their register so that sales do not print, they can enter a sale that they intend to skim yet ensure that the sale never appears on the books. Anyone observing the employee sees the sale entered, and the cash drawer open, yet the register tape does not reflect the transaction. How is this accomplished?

Consider a service station employee who hid stolen gasoline sales by simply lifting the ribbon from the printer. He then collected and pocketed the sales that were not recorded on the register tape. The fraudster then rolled back the tape to the point where the next transaction should appear and replaced the ribbon. The next transaction was printed without leaving any blank space on the tape, apparently leaving no trace of the fraud. However, the fraudster had overlooked that the transactions on his register were prenumbered. Even though he was careful to replace the register tape, he failed to realize that he was creating a break in the sequence of transactions. For instance, if the perpetrator skimmed sale #155, the register tape would show only transactions #153, #154, #156, #157, and so on. The missing transaction numbers that were omitted because the ribbon was lifted when the sales took place raised a red flag.

Special circumstances can lead to more creative methods for skimming at the register.

In another situation, a movie theater manager figured out a way around the theater’s automatic ticket dispenser. In order to reduce payroll hours, this manager sometimes worked as a cashier, selling tickets. He made sure, at these times, that there was no one checking patrons’ tickets outside the theaters. When a sale was made, the ticket dispenser fed out the appropriate number of tickets, but the manager withheld tickets from some patrons and allowed them to enter the theater without them. When the next customer made a purchase, the manager sold her one of the excess tickets, instead of using the automatic dispenser. Thus, portions of the ticket sales were not recorded. At the end of the night, there was a surplus of cash, which the manager removed and kept for himself. Although the actual loss was impossible to measure, it was estimated that this manager stole over $30,000 from his employer.

After-Hours Sales

Another way to skim unrecorded sales is to conduct sales during nonbusiness hours. For instance, some employees have been caught running their employers’ stores on weekends or after hours without the knowledge of the owners. They were able to pocket the proceeds of these sales because the owners had no idea that their stores were even open. One manager of a retail facility in an unusual fraud case went to work two hours early every day, opening his store at 8:00 a.m. instead of 10:00 a.m., and pocketed all the sales made during these two hours. Talk about dedication! He rang up sales on the register as if it were business as usual, but then he removed the register tape and all the cash that he had accumulated. The manager then started from scratch at 10:00, as if the store were just opening. The tape was destroyed, so there was no record of the before-hours revenue. One might be thinking that off-book sales create not only a cash shortage but an inventory shortage as well—true! But, inventory shrinkage can be the result of damaged goods not removed from the inventory system, inventory lost in shipping but not properly accounted for, theft by nonemployees, and other reasons. That said, unusual amounts of inventory shrinkage may be a symptom of fraud.

Skimming by Off-Site Employees

Although we have discussed skimming in the context of cash register transactions, skimming does not have to occur at a register or even involve hard currency. Employees who work at remote locations or without close supervision perpetrate some of the most costly skimming schemes. This can include independent salespeople who operate off-site and employees who work at branches, satellite, and international offices. These employees may have a high level of autonomy in their jobs, which often translates into inadequate levels of supervision and, in turn, to fraud.

Several cases involved the skimming of sales by off-site employees. Some of the best examples of this type of fraud occur in the apartment rental industry, where apartment managers handle the day-to-day operations without much oversight. A common scheme, as evidenced by a bookkeeper in one fraud, is for the perpetrator to identify the tenants who pay in currency and remove them from the books. This causes a particular apartment to appear as vacant on the records, although, in fact, it is occupied. Once the currency-paying tenants are removed from the records, the manager can skim their rental payments. As long as no one physically checks the apartment, the fraudster can continue skimming indefinitely.

Another rental skimming scheme occurs when apartments are rented, but no lease is signed. On the books, the apartment still appears to be vacant, even though there are rent-paying tenants on the premises. The fraudster can then steal the rent payments, which are not missed. Sometimes the employees in these schemes work in conjunction with the renters and give a “special rate” to these people. In return, the renters’ payments are made directly to the employee, and any complaints or maintenance requests are directed only to that employee, so that the renters’ presence remains concealed.

Instead of skimming rent, the property manager in another case skimmed payments made by tenants for application fees and late fees. Revenue sources such as these are less predictable than rental payments, and their absence are, therefore, harder to detect. The central office knew when rent was due and how many apartments were occupied, but it had no controls in place to track the number of people who filled out rental applications or how many tenants paid their rent a day or two late. Stealing only these nickel-and-dime payments, the property manager in this case was able to make off with approximately $10,000 of her employer’s money.

A similar revenue source that is unpredictable and therefore difficult to account for is parking lot collection revenue. In one example, a parking lot attendant skimmed approximately $20,000 from his employer, simply by not preparing tickets for customers who entered the lot. He would take the customers’ money and wave them into the lot, but because no receipts were prepared by the fraudster, there was no way for the victim company to compare tickets sold to actual customers at this remote location. Revenue sources that are hard to monitor and predict, such as late fees and parking fees in the preceding examples, are prime targets for skimming schemes.

Another off-site person in a position to skim sales is the independent salesperson. A prime example is the insurance agent who sells policies but does not file them with the carrier. In one example, the owner of an independent insurance company discovered a theft when his most valued and trusted agent called in sick; during the employee’s absence, a potential out-of-state “customer” called the insurance company’s office. The issue: the company did not offer insurance in that market nor was it licensed to sell insurance in that state. Most customers try not to file a claim on a policy, especially early in the term, for fear that their premium will rise. Knowing this, the fraudster agent maintained all documentation on the policies, instead of submitting them to the carrier. The agent then collected and kept the policy payments, because the carrier did not know the policy existed. Customers continued to make their payments, thinking they were insured. When a customer eventually filed a claim, the agent backdated the fake policy, submitted it to the carrier, and then filed the claim so that the fraud remained undetected. If the company had instituted a simple internal control—the requirement for policyholders to contact the company directly with any claims—the fraud may have been discovered.

Poor Collection Procedures

Poor collection and recording procedures can make it easy for an employee to skim sales or receivables. In one case, a governmental authority that dealt with public housing was victimized because it failed to itemize daily receipts. This agency received payments from several public housing tenants, but, at the end of the day, money received from tenants was listed as a whole. Receipt numbers were not used to itemize the payments made by tenants, so there was no way to identify the source and amounts of tenant payments. Consequently, the employee in charge of collecting rent from tenants was able to skim a portion of their payments. She ultimately failed to record receipt of more than $10,000.

Understated Sales

The prior cases dealt with purely off-book sales. Understated sales work differently, in that the transaction is posted to the books, but for a lower amount than the perpetrator collected from the customer (see Figure 4-2). For example, an employee wrote receipts to customers for their purchases, but she removed the carbon-paper backing on the receipts so that they did not produce a company copy. The employee then used a pencil to prepare company copies that showed lower purchase prices. For example, if the customer had paid $100, the company copy might reflect a payment of $80. The employee skimmed the difference between the actual amount of revenue and the amount reflected on the fraudulent receipt. This can also be accomplished at the register when the fraudster underrings a sale, by entering a sale total that is lower than the amount actually paid by the customer. The employee skims the difference between the actual purchase price of the item and the sales figure recorded on the register. In some cases, rather than reduce the price of an item, an employee might record the sale of fewer items. If 100 units are sold, a fraudster might only record the sale of 50 units and skim the excess cash. The successful concealment of this type of fraud necessitates that the customer would not be given a receipt.

FIGURE 4-2 Understated sales

Check-for-Currency Substitutions

Another common skimming scheme is to take unrecorded checks that the perpetrator has stolen and substitute them for receipted currency. This type of scheme is especially common when the fraudster has access to incoming funds from an unusual source, such as refunds or rebates that are not expected by the victim organization. The benefit of substituting checks for cash, from the fraudster’s perspective, is that stolen checks payable to the victim organization may be difficult to convert. They also leave an audit trail showing where the stolen check was deposited. Currency, on the other hand, disappears into the economy once it has been spent.

An example of a check-for-currency substitution was found in a fraud where an employee responsible for receipting ticket and fine payments on behalf of a municipality abused her position and stole incoming revenues for nearly two years. When this individual received payments in cash, she issued receipts, but, when checks were received, she did not. The check payments were therefore unrecorded revenues—ripe for skimming. These unrecorded checks were then placed in the days’ receipts, and an equal amount of cash was removed. The receipts matched the amount of money on hand, except that payments in currency had been replaced with checks.

Theft in the Mailroom—Incoming Checks

Another common form of skimming occurs in the mailroom, where employees charged with opening the daily mail simply take incoming checks instead of processing them. The stolen payments are not posted to the customer accounts, and, from the victim organization’s perspective, it is as if the check had never arrived (see Figure 4-3). When the task of receiving and recording incoming payments is left to a single person, it is all too easy for that employee to slip an occasional check into his or her pocket.

FIGURE 4-3 Theft of incoming checks

An example of a check theft scheme is where a mailroom employee stole over $2 million in government checks arriving through the mail. This employee simply identified and removed envelopes delivered from a government agency that was known to send checks to the company. Using a group of accomplices, acting under the names of fictitious persons and companies, this individual was able to launder the checks and divide the proceeds with his cronies.

Mixed Systems and System Interfaces

Many readers might be thinking that many of the schemes and their descriptions suggest manual systems. In a computerized world, are these schemes really possible? The short answer is yes. The more complicated response is that yes, computers systems are everywhere. At the same time, most organizations consist of “mixed use” systems—some aspects are computerized, while others are transacted the old-fashioned way. A thorough and thoughtful review of organization systems will likely reveal a complicated variety of manual and electronic systems. The manual systems are at risk for exploitation as described in this text, while the computerized transactions require adjustments in order for the scheme to succeed in both the act and the concealment. Frequently, those adjustments are reasonable in appearance but costly in losses to the company. Interfaces between manual and computer systems create new opportunities to help fraudsters facilitate and conceal their bad acts. That is why antifraud professionals are always looking for unusual transactions, patterns, and changes in patterns. These anomalies are often just the tip of the iceberg. Interestingly, discussions with auditors suggest that some of their biggest risks arise not from highly computerized systems but rather from complicated interfaces between electronic and manual systems.

Preventing and Detecting Sales Skimming

Perhaps the key to preventing skimming is to maintain a viable oversight presence at any point where cash enters an organization. Recall that the second leg of Cressey’s fraud triangle involved a perceived opportunity to commit the fraud and get away with it. When an organization establishes effective oversight, it diminishes the perception among employees that they would be able to steal without getting caught.

It is important to have a visible management presence at all cash entry points, including cash registers and the mailroom. That doesn’t mean that a manager must hover over cashiers and mailroom clerks at all times—too much oversight can have a negative effect on employees, causing them to feel mistrusted or resentful of management. But managers should routinely check cash entry points—not just for signs of fraud, but also to ensure proper customer service, monitor productivity, and so forth.

Organizations do not have to rely solely on management to oversee cash collections. In retail organizations that utilize several cash registers, the registers are frequently placed in one “cluster” area, rather than spread throughout the store. A reason for this is so that cashiers are working in full view of other employees, as well as customers, and this serves to deter skimming.

Instead of a physical management presence, video cameras can be installed at cash entry points to serve essentially the same purpose. The principal benefit of video cameras is not just that the cameras might detect theft, but that their use might also deter employees from attempting to steal. Incidentally, a 24-hour video monitoring system may prevent off-hours sales.

Customers can also be utilized in the monitoring function by serving to inform a manager when not getting a receipt at the time of purchase, as explained earlier in this chapter. The purpose of these programs is to force employees to ring up sales, thereby making it more difficult to commit an unrecorded sales scheme. In addition, customer complaints and tips are a frequent source of detection for all types of occupational fraud, including skimming. Calls from customers for whom there is no record, for example, are a clear red flag of fraud. Customer complaints should be received and investigated by employees who are independent of the sales staff.

All cash registers should record the log-in and log-out time of each user. This simple measure makes it easy to detect off-hours sales by comparing log-in times to the organization’s hours of operation. In addition, if a theft occurs, the user log is helpful to identify the potential culprit.

Off-site sales personnel should also be required to maintain activity logs to account for all sales visits and other business-related activities. These logs should include information such as the customer’s name, address, and phone number; the date and time of the meeting; and the result of the meeting (e.g., was a sale made?). Employees independent of the sales function can spot-check the veracity of the entries by making “customer satisfaction calls,” in which the customer is asked to verify the information recorded in the activity log.

In addition to monitoring, organizations can take other steps to reduce employees’ perceived opportunity to steal. For example, it is advisable, particularly in busy retail establishments, to maintain a secure area where cashiers are required to store coats, hats, purses, and so on. The idea is to eliminate potential hiding places for stolen money.

In the mailroom, employees who open incoming mail should do so in a clear, open area that is free from blind spots. Preferably, to deter thefts, there should be a supervisory presence or video monitoring in place when mail is opened. At least two employees should be involved with opening the organization’s mail and logging incoming payments, so that one is not able to steal incoming checks without the other noticing.

Big Data and Data Analytics

Whether the organization has one register or thousands, most are now electronically connected to a computer system that records not only traditional transaction information but also includes date and time stamps, ISPs and other information. While not conclusive in terms of fraud detection, data analytics and big data techniques can be used to highlight anomalous transaction activity across time, by location, by employee, by terminal, etc. As an example, some “voided” transactions are expected as transactions are occasionally recorded in error. However, data analysis can point antifraud and forensic accounting professionals in the direction of those most likely perpetrating a skimming scheme when “error correction efforts” do not align with similar patterns of prior activities. Once suspected, electronic evidence is isolated using big data and data analytics tools, supplemental evidence gathered from a deeper examination of the details can be accumulated to conclusively prove whether the anomalies are part of a fraud scheme or are explainable based on the totality of the evidence.

Module 2: Skimming Schemes—Receivables

As outlined in “Fraud Casebook: Lessons from the Bad Side of Business,” Chapter 56 (Wiley, 2007), the auditor “became concerned about unusual reconciliation items between the accounts receivable detailed list of balances due and the general ledger, reconciling items without support. The audit senior shared her concerns with the company’s controller, who spent a long, late evening examining accounts receivable records. The accounts receivable posting process had not been followed recently and the accounts receivable clerk had fudged the accounts receivable reconciliation. The controller concluded his evening by preparing a formal reprimand to present to accounts receivable clerk for ‘not following policy and procedure,’ including improper posting of deposits and failure to clear invoices per the customer remittance.”

The next morning, the accounts receivable clerk stopped reporting to work and the examination became more urgent. Months of work revealed the following major anomalies:

- No apparent follow-up with customers regarding unpaid invoices.

- Deposits from one customer were posted to another.

- Payments posted to “balances” instead of clearing specific invoices as paid.

- Payments applied to the oldest open invoices instead of those listed on the check remittance.

- In a few instances, credit memos were posted to write off unpaid invoices.

- No apparent follow-up when customers claimed inappropriate discounts.

The company had an excellent review process in place; every Monday morning, the accounts receivable subledger was reviewed in detail by the VP of sales, the controller, and, most weeks, the owner. In this control environment, how did accounts receivable balances not balloon and the accounts receivable aging not reveal unpaid old invoices?

The answer to that question is relatively simple.

As described in the Fraud Casebook, a lack of supervision provided an environment that allowed the accounts receivable clerk to operate unimpeded. The accounts receivable clerk was a quiet and shy person much more comfortable working with the company’s books and records than spending time on the phone contacting customers. So instead of tracking down unpaid invoices, the clerk spent time using the accounts receivable system’s debit and credit memos. Every Friday afternoon, in preparation for Monday’s customer service meeting, the accounts receivable clerk would write off all of the old unpaid invoices. It was this “cleaned up” version of the accounts receivable subledger that was presented to and reviewed by company leadership. Then, on Monday afternoon, the accounts receivable clerk spent time reversing all of the credit memos with debit memos. A detailed review of the debit and credit memos posted to the system during the examination revealed a clear and distinct pattern.

A customer-by-customer reconciliation process took almost four months and revealed a staggering $2 million in unexpected, unpaid, older accounts receivable balances. The investigation revealed that the accounts receivable clerk had stolen no checks or money; however, in an effort to keep his job the clerk had cost his company millions in uncollectible accounts receivable losses. In addition, the reconstruction process cost another $125,000.

Despite this gloom, all was not lost. The company had an all-risk property insurance policy that included a rider for accounts receivable, one that specifically included fraud losses (typically the only way that fraud is covered by insurance). Ultimately, the insurance carrier reimbursed the company for the reconstruction costs and covered a portion of the accounts receivable losses, leaving the company with a $1 million loss, which was greater than a year’s profit, even in the best of times.

Skimming receivables requires more effort than skimming sales. Consequently, they are more complicated to perpetrate and conceal. Incoming receivables payments are expected, so the victim organization is likely to notice if these payments are not received and posted to the accounting system. As receivables become past due, most organizations send notices of nonpayment to its customers. Customers generally complain when they receive a second bill for a payment they have already made. In addition, the customer’s cashed check serves as evidence that the payment was made. When fraudsters attempt to skim receivables, they usually use one of the following techniques to conceal the thefts:

- Lapping

- Force balancing

- Stolen statements

- Fraudulent write-offs or discounts

- Debiting the wrong account

- Document destruction

Lapping

Lapping customer payments is one of the most common methods of concealing receivables skimming. Lapping is the crediting of one account through the abstraction of money from another account. It is the fraudster’s version of “robbing Peter to pay Paul.” Suppose a company has three customers, A, B, and C. When A’s payment is received, the fraudster takes it for himself instead of posting it to A’s account. Customer A expects that his account will be credited with the payment he has made, but this payment has actually been stolen. When A’s next statement arrives, he sees that his check was not applied to his account, and he complains. To avoid this, some action must be taken to make it appear that the payment was posted.

When B’s check arrives, the fraudster takes this money and posts it to A’s account. Payments now appear to be up-to-date on A’s account, but B’s account is short. When C’s payment is received, the perpetrator applies it to B’s account. This process continues indefinitely until one of three things happens: (1) someone discovers the scheme, (2) restitution is made to the accounts, or (3) some concealing entry is made to adjust the accounts receivable balances.

It should be noted that, although more commonly used to conceal skimmed receivables, lapping could also be used to disguise the skimming of sales. In one actual situation, a store manager stole daily receipts and replaced them with the following day’s incoming cash. She progressively delayed making the company’s bank deposits, as more and more money was taken. Each time a day’s receipts were stolen, it took an extra day of collections to cover the missing money. Eventually, the banking irregularities became so great that an investigation was commenced. It was discovered that the manager had stolen nearly $30,000 and concealed the theft by lapping her store’s sales.

A Ponzi scheme, such as the one Bernard Madoff perpetrated, contains the essential elements of lapping in that money from new investors was used to pay off what was “owed” to earlier investors.

Because lapping schemes can become very intricate, fraudsters sometimes keep a second set of books on hand, detailing the true nature of the payments received. In many skimming cases, a search of the fraudster’s work area reveals a set of records tracking the actual payments made and how they have been misapplied to conceal the theft. It may seem odd for someone to keep on hand records of his or her illegal activity, but many lapping schemes become complicated, as more and more payments are misapplied. The second set of records helps the perpetrator keep track of what funds he or she has stolen and what accounts need to be credited to conceal the fraud. Uncovering these records, if they exist, greatly aids the investigation of a lapping scheme.

Force Balancing

Among the most dangerous receivables skimming schemes are those where the perpetrator is in charge of collecting and posting payments. If a fraudster has a hand in both ends of the receipting process, he or she can falsify records to conceal the theft of receivables payments. For example, the fraudster might post an incoming payment to a customer’s receivables account, even though the payment is never deposited. This keeps the receivable from aging, but it creates an imbalance in the cash account. The perpetrator hides the imbalance by forcing the total on the cash account, overstating it to match the total postings to accounts receivable.

Stolen Statements

Another method used by employees to conceal the misapplication of customer payments is the theft or alteration of account statements. If a customer’s payments are stolen and not posted, his or her account becomes delinquent. When this happens, the customer should receive late notices or statements showing that the account is past due. The purpose of altering customers’ statements is to keep them from complaining about the misapplication of their payments.

To keep customers unaware about the true status of their accounts, some fraudsters intercept their account statements or late notices. This might be accomplished, for instance, by changing the customer’s address in the billing system. The statements are sent directly to the employee’s home or to an address where he or she can retrieve them. In other cases, the address is changed so that the statement is undeliverable, which causes the statements to be returned to the fraudster’s desk. In either situation, once the employee has access to the statements, he or she can do one of two things. The first option is to throw the statements away. This is not particularly effective, especially if customers ever request information on their accounts after not having received a statement.

Therefore, the fraudster may instead choose to alter the statements or to produce counterfeit statements to make it appear that the customers’ payments have been properly posted. The fraudster then sends these fake statements to the customers. The false statements lead the customers to believe that their accounts are up-to-date and thus keep them from complaining about stolen payments.

Fraudulent Write-Offs or Discounts

Intercepting the customers’ statements keeps them in the dark as to the status of their accounts, but the problem still remains that as long as the customers’ payments are being skimmed, their accounts are slipping further and further past due. The fraudster must find some way to bring the accounts back up-to-date in order to conceal his or her crime. As we have discussed, lapping is one way to keep accounts current as the employee skims from them. Another way is to write off the customers’ accounts fraudulently. For example, an employee skimmed cash collections and wrote off the related receivables as “bad debts.” Similarly, in another case, a billing manager was authorized to write off certain patient balances as hardship allowances. This employee accepted payments from patients and then instructed billing personnel to write off the balance in question. The payments were never posted, because the billing manager intercepted them. She covered approximately $30,000 in stolen funds by using her authority to write off patients’ account balances.

Instead of writing off accounts as bad debts, some employees cover their skimming by posting entries to contra revenue accounts, such as “discounts and allowances.” If, for instance, an employee intercepts a $1,000 payment, he or she might create a $1,000 “discount” on the account to compensate for the missing money. Providing customers with false discounts is a common technique to conceal a fraudulent skimming scheme.

Debiting the Wrong Account

Fraudsters also debit existing or fictitious accounts receivable in order to conceal skimmed cash. As an example, an office manager in a health-care facility took payments from patients for herself. To conceal her activity, the office manager added the amounts taken to the accounts of other patients that she knew would soon be written off as uncollectable. The employees who use this method generally add the skimmed balances to accounts that are either very large or are aging and about to be written off. Increases in the balances of these accounts are not as noticeable as in other accounts. In this case, once the old accounts were written off, the stolen funds were written off along with them.

Rather than existing accounts, some fraudsters set up completely fictitious accounts and debit them for the cost of skimmed receivables. The employees then simply wait for the fictitious receivables to age and be written off, knowing that they are uncollectible. In the meantime, they carry the cost of a skimming scheme where it is not detected.

Destroying or Altering Records of the Transaction

Finally, when all else fails, a perpetrator may simply destroy an organization’s accounting records in order to cover his or her tracks. For instance, we have already discussed the need for a salesperson to destroy the store’s copy of a receipt in order for the sale to go undetected. Similarly, cash register tapes may be destroyed to hide an off-book sale. In one situation, two management-level employees skimmed approximately $250,000 from their company over a four-year period. These employees tampered with cash register tapes that reflected transactions in which sales revenues had been skimmed. The perpetrators either destroyed entire register tapes or cut off large portions where the fraudulent transactions were recorded. In some circumstances, the employees then fabricated new tapes to match the cash on hand and make their registers appear to balance.

Discarding transaction records is often a last-ditch method for a fraudster to escape detection; the fact that records have been destroyed may itself signal that fraud has occurred. Nevertheless, without the records, it can be very difficult to reconstruct the missing transactions and prove that someone actually skimmed money. Furthermore, it may be difficult to prove who was involved in the scheme.

Preventing and Detecting Receivables Skimming

Receivables skimming schemes typically succeed when there is a breakdown in an organization’s controls, particularly when one individual has too much control over the process of receiving and recording customer payments, posting cash receipts, or issuing customer credits. If the accounting duties associated with accounts receivable are properly separated, so that there are independent checks of all transactions, skimming of these payments is very difficult to commit and very easy to detect. For example, when force balancing is used to conceal skimming of receivables, it causes a shortage in the organization’s cash account, because incoming payments are not deposited. By simply reconciling its bank statement regularly and thoroughly, an organization ought to be able to catch this type of fraud. Similarly, when an individual skims receivables but continues to post the payments to customer accounts, postings to accounts receivable exceeds what is reflected in the daily deposit. If an organization assigns an employee to verify independently that deposits match accounts receivable postings, this type of scheme ought to be quickly detected, or, more likely, it is not attempted at all. It is also a good idea to have that employee spot-check deposits to accounts receivable, to ensure that payments are being applied to the proper accounts. If a check was received by customer A, but the payment was posted to customer B’s account, this indicates a lapping scheme.

As discussed earlier, lapping schemes can become very complicated, and they may require the perpetrator to spend long hours at work, trying to shift funds around in order to conceal the crime. Ironically, it is actually very common in these cases for the perpetrator to develop a reputation as a model employee, because of all the overtime that he or she puts in at the office. After the frauds come to light, the employers frequently express shock—not only because they were defrauded, but also because they had considered the perpetrator to be one of their best employees. The point is that a lapping scheme can only succeed through the constant vigilance of the perpetrator. Because of this fact, many organizations mandate that their employees take a vacation every year or regularly rotate job duties among employees. Both of these tactics can be successful in uncovering lapping schemes, because they effectively take control of the books out of the perpetrator’s hands for a period of time, and, when this happens, the lapping scheme quickly becomes apparent.

It is also important to mandate supervisory approval for write-offs or discounts to accounts receivable. As we have seen, fraudulent write-offs and discounts are a common means by which the skimming of receivables is concealed; they enable the fraudster to wipe the stolen funds off the books. However, if the person who receives and records customer payments has no authority to make these adjustments, the perceived opportunity to commit the crime is severely diminished. Consistent with this concern, all journal entries should be scrutinized for proper supporting documentation, reviews, and approvals.

Although strong internal controls are a valuable preventative tool, the fact remains that fraud can and does continue to occur, regardless of the existence of controls designed to prevent it. Organizations must also be able to detect fraud once it has occurred. Some detection methods are very simple. For example, fraudsters sometimes conceal the theft of receivables by making alterations or corrections to books and records. Physical alterations to financial records, such as erasures or cross-outs, are often a sign of fraud, as are irregular entries to miscellaneous accounts. Audit staff should be trained to investigate these red flags.

It is also important for organizations to search out proactively the accounting clues that point to fraud. This can be tedious, time-consuming work, but computerized audit tools allow organizations to automate many of these tests and greatly aid in the process of searching out fraudulent conduct.

The key to using automated tests successfully is in designing them to highlight the red flags that are typically associated with a particular scheme. For example, we have seen that fraudsters often conceal the skimming of receivables by writing off the amount of funds they have stolen from the targeted account. To detect this kind of activity, organizations can run reports summarizing the number of discounts, adjustments, returns, write-offs, and so on that have been generated by location, department, or employee. Unusually high levels may be associated with skimming schemes and could warrant further investigation. Because some fraudsters conceal their skimming by debiting accounts that are aging or that typically have very little activity, it may also be helpful to run reports looking for unusual activity in otherwise dormant accounts.

Trend analysis on aging of customer accounts can likewise be used to highlight a skimming scheme. A significant rise in the number or size of overdue accounts could be a result of an employee who has stolen customer payments without ever posting them, thereby causing the accounts to run past due. If skimming is suspected, an employee who is independent of the accounts receivable function should confirm overdue balances with customers.

There are several big data/data analytic audit tests that can be used to help detect various forms of occupational fraud. In each chapter of this book where fraud schemes are examined, we provide a set of proactive data analytic audit tests that are tailored to that particular category of fraud. These tests were developed and accumulated by Richard Lanza, working through the Institute of Internal Auditors Research Foundation.

Big Data and Data Analytic Techniques for Detecting Skimming

| Title | Category | Description | Data file(s) |

| Summarize net sales by employee and extract top ten employees with low sales. | All | Employees with lower sales may be a suspect. This test may also prove more valuable when executed over a trend in time. |

|

| Summarize by location discounts, returns, inventory adjustments, accounts receivable write-offs, and voids charged. | All | Locations with high adjustments may signal actions to hide skimming schemes. |

|

| Summarize by employee discounts, returns, inventory adjustments, accounts receivable write-offs, and voids charged. | All | Employees with high adjustments may signal actions to hide skimming schemes. |

|

| List top 100 employees by dollar size (one for discounts, one for refunds, one for inventory adjustments, one for accounts receivable write-offs, and one for sale voids). | All | Employees with high adjustments may signal actions to hide skimming schemes. |

|

| List top 100 employees who have been on the top 100 list for three months (one for discounts, one for refunds, one for inventory adjustments, one for accounts receivable write-offs, and one for sale voids). | All | Employees with high adjustments may signal actions to hide skimming schemes. |

|

| List top ten locations that have been on the top ten list for three months (one for discounts, one for refunds, one for inventory adjustments, one for accounts receivable write-offs, and one for sale voids). | All | Locations with high adjustments may signal actions to hide skimming schemes. |

|

| Compute standard deviation for each employee for the last three months, and list those employees that provided three times the standard deviation in the current month (one for discounts, one for refunds, one for inventory adjustments, one for accounts receivable write-offs, and one for sale voids). | All | Employees with high adjustments may signal actions to hide skimming schemes. |

|

| Compare adjustments to inventory to the void/refund transactions summarized by employee. | All | First, a summary of adjustments by inventory number (SKU number) and employee is completed, which is then compared to credit adjustments (to decrease inappropriately inventory that was supposedly returned) by inventory number. |

|

| Summarize user access for the sales, accounts receivable, inventory, and general ledger systems for segregation of duties reviews. | All | User access to systems may identify segregation of duties issues. For example, if an employee can make changes to the accounts receivable system and then post other concealment entries in the general ledger, such nonsegregation of duties would allow an employee to hide his or her actions. User access should be reviewed from the perspective of adjustments within the application and adjustments to the data themselves. |

|

| Summarize user access for the sales, accounts receivable, inventory, and general ledger systems in nonbusiness hours. | All | Many times, concealment adjustments are made in nonbusiness hours. User access should be reviewed from the perspective of adjustments within the application and adjustments to the data themselves. |

|

| Compute the percentage of assigned to unassigned time for employees. | All | Service employees that have a high majority of unassigned time may be charging the customer and pocketing the proceeds. |

|

| Review telephone logs for calls during nonbusiness hours. | All | Service employees that are completing transactions during nonbusiness hours probably use company lines to effectuate their services. |

|

| Extract sales with over X percent discount and summarize by employee. | Understated sales | Employees with high discount adjustments may signal actions to hide understated sales schemes. |

|

| Extract invoices with partial payments. | Understated and refunds & other | Employees who are using lapping to hide their skimming scheme may find it difficult to apply a payment from one customer to another customer’s invoices in a fully reconciled fashion. |

|

| Join the customer statement report file to accounts receivable and review for balance differences. | Understated and refunds & other | Through the matching of the customer statement report file (file that is used to print customer statements) and the open invoices to that customer, any improper changes to customer statements to mask skimming schemes are detected. |

|

| Extract customer open invoice balances that are in a credit position. | Understated and refunds & other | Customers with a credit position account may be due to improper credit entries posted to the customer account to hide cash skimming. |

|

| Extract customers with no telephone or tax ID number. | Understated and refunds & other | Customers without this information may have been created for use in posting improper entries to hide a skimming scheme. |

|

| Identify customers added during the period under review. | Understated and refunds & other | The issuers of new customer additions should be reviewed, using this report to determine whether an employee is using phony customer accounts as part of a lapping scheme by crediting their account for cash misappropriation. |

|

| Match the customer master file to the employee master file on various key fields. | Understated and refunds & other | Compare telephone number, address, tax ID numbers, numbers in the address, PO box, and zip code in customer file to employee file, especially those employees working in the accounts receivable department. Questionable customer accounts should be reviewed, using this report to determine whether an employee is using phony customer accounts as part of a lapping scheme by crediting their account for cash misappropriation. |

|

Module 3: Cash Larceny Schemes

According to FoxNews.com (September 13, 2011), California Senator Diane Feinstein claimed that her campaigns cash had been looted by a Democratic treasurer who she likened to Bernie Madoff.1 Feinstein’s campaign blamed Kinde Durkee, who managed the senator’s finances for years along with the accounts of several other top California politicians. The article stated that Durkee had authority over more than 400 bank accounts, including political campaigns. Senator Feinstein’s office said the senator was “wiped out” along with the other lawmakers. According to the article, Durke committed the following acts to take the cash and conceal her activities:

- Comingled clients’ funds, making it difficult to understand whose money went where

- Routinely placed substantial sums of money into her company accounts, or channeled to other campaigns, apparently when suspicions were raised about missing money

- Falsely reported account balances

- Used an elaborate shell game to shift money out of state

Federal prosecutors and others believe that Durkee siphoned the cash to pay credit cards, a mortgage, business bills, and an array of debts from shopping at Costco to her mother’s care at an assisted-living facility. Durkee was arrested and hit with fraud charges when U.S. Rep. Susan Davis, also of California, asserted that her campaign was robbed of about $250,000.

In the occupational fraud setting, a cash larceny may be defined as the intentional taking away of an employer’s cash (the term cash includes both currency and checks) without the consent and against the will of the employer.

Cash receipts schemes are what we typically think of as the outright stealing of cash. The perpetrator does not rely on the submission of phony documents or the forging of signatures; he or she simply grabs the cash and takes it. The cash receipts schemes fall into two categories: skimming, which we have already discussed, and cash larcenies. Remember that skimming was defined as the theft of off-book funds. Cash larceny schemes, on the other hand, involve the theft of money that has already appeared on a victim company’s books.

A cash larceny scheme can take place in any circumstance in which an employee has access to cash. Every company must deal with the receipt, deposit, and distribution of cash (if not, it certainly will not be a very long-lived company!), so every company is potentially vulnerable to this form of fraud. Although the circumstances in which an employee might steal cash are nearly limitless, most larceny schemes involve the theft of cash:

- At the point of sale

- From incoming receivables

- From the victim organization’s bank deposits

Larceny at the Point of Sale

A large percentage of the cash larceny schemes occur at the point of sale, and for good reason—that’s where the money is. The cash register (or similar cash collection points, such as cash drawers, church collection baskets, or cash boxes) is usually the most common point of access to ready cash for employees, so it is understandable that larceny schemes frequently occur there. Furthermore, there is often a great deal of activity at the point of sale—particularly in retail organizations—with multiple transactions requiring the handling of cash by employees. This activity can serve as a cover for the theft of cash. In a flurry of activity, with cash being passed back and forth between customer and employee, a fraudster is more likely to be able to slip currency out of the cash drawer and into his or her pocket without getting caught.

This is the most straightforward scheme: the fraudster opens up the register and removes currency (see Figure 4-4). It might be done as a sale is being conducted to make the theft appear to be part of the transaction, or perhaps when no one is around to notice the perpetrator digging into the cash drawer. For instance, a teller simply signed onto a cash register, rang a “no sale,” and took currency from the drawer. Over a period of time, the teller took approximately $6,000 through this simple method.

FIGURE 4-4 Cash larceny from the register

Recall that the benefit of a skimming scheme is that the transaction is unrecorded, and the stolen funds are never entered on company books. Employees who are skimming either underring the register transaction so that a portion of the sale is unrecorded or they completely omit the sale by failing to enter it at all on their register. This makes the skimming scheme difficult to detect, because the register tape does not reflect the presence of the funds that have been taken. In a larceny scheme, on the other hand, the funds that the perpetrator steals are already reflected on the register tape. As a result, an imbalance results between the register tape and the cash drawer. This imbalance should be a signal that alerts a victim organization to the theft.

The actual method for taking money at the point of sale—opening a cash drawer and removing currency—rarely varies. But the methods used by fraudsters to avoid getting caught are what distinguish larceny schemes. Oddly, in many cases, the perpetrator has no concealment plan for avoiding detection. A large part of fraud is rationalizing; fraudsters convince themselves that they are somehow entitled to what they are taking or that what they are doing is not actually a crime. Cash larceny schemes frequently begin when perpetrators convince themselves that they are only “borrowing” the funds to cover a temporary monetary need. These people might carry the missing cash in their registers for several days, deluding themselves in the belief that they will one day repay the funds and hoping that their employers will not perform a surprise cash count until the missing money is replaced.

Employees who do nothing to camouflage their crimes are easily caught (if someone is paying attention); more dangerous are those who take active steps to hide their misdeeds. In the cash larceny schemes reviewed, there were several methods used to conceal larceny that occurred at the point of sale:

- Thefts from other registers

- Death by a thousand cuts

- Reversing transactions

- Altering cash counts or register tapes

- Destroying register tapes

Thefts from Other Registers

One basic way for an employee to disguise the fact that he or she is stealing currency is to take money from someone else’s cash register. In some retail organizations, employees are assigned to certain registers. Alternatively, one register is used and each employee has an access code. When cash is missing from a cashier’s register, the most likely suspect for the theft is obviously that cashier. Therefore, by stealing from another employee’s register, or by using someone else’s access code, the fraudster makes sure that another employee will be the prime suspect in the theft. In the prior case, the employee who stole money did so by waiting until another teller was on break and then logging onto that teller’s register, ringing a “no sale,” and taking the cash. The resulting cash shortage, therefore, appeared in the register of an honest employee, deflecting attention from the true thief. In another case, a cash office manager stole over $8,000, in part by taking money from cash registers and making it appear that the cashiers were stealing.

Death by a Thousand Cuts

A very unsophisticated way to avoid detection is to steal currency in very small amounts over an extended period of time. This is the “death by a thousand cuts” larceny scheme: $15 here, $20 there, and, slowly, the culprit bleeds his or her company. Because the missing amounts are small, the shortages may be credited to errors rather than theft. Typically, the fraudulent employees become dependent on the extra money that they are pilfering, and their thefts increase in scale or become more frequent, which causes the scheme to be uncovered. Most retail organizations track overages or shortages by employee, making this method largely ineffectual.

Reversing Transactions

Another way to conceal cash larceny is to use reversing transactions, such as false voids or refunds, which cause the register tape to reconcile to the amount of cash on hand after the theft. By processing fraudulent reversing transactions, an employee can reduce the amount of cash reflected on the register tape. For instance, a cashier received payments from a customer and recorded the transactions on her system. She later stole those payments and then destroyed the company’s receipts that reflected the transactions. To complete the cover-up, the cashier went back and voided the transactions, which she had entered when the payments were received. The reversing entries brought the receipt totals into balance with the cash on hand. (These schemes are discussed in more detail in Chapter 5.)

Altering Cash Counts or Cash Register Tapes

A cash register is balanced by comparing the transactions on the register tape with the amount of cash on hand. Starting at a known balance, sales, returns, and other register transactions are added to or subtracted from the balance to arrive at a total for the period in question. The actual cash is then counted, and the two totals are compared. If the register tape shows that there should be more cash in the register than is present, it may be because of larceny. To conceal cash larceny, some fraudsters alter the cash counts from their registers to match the total receipts reflected on their register tape. For example, if an employee processes $1,000 worth of transactions on a register and then steals $300, there is only $700 left in the cash drawer. The employee can falsify the cash count by recording that $1,000 is on hand, so that the cash count balances to the register tape. This type of scheme occurred in one case when a fraudster not only discarded register tapes to conceal her thefts but also erased and rewrote cash counts for the registers from which she pilfered. The new totals on the cash count envelopes were overstated by the amount of money she had stolen, reflecting the actual receipts for the period and balancing with the cash register tapes. Under the victim company’s controls, this employee was not supposed to have access to cash. Ironically, coworkers praised her dedication for helping them count cash when it was not one of her official duties.

Instead of altering cash counts, some employees manually alter the register tape from their cash registers. Again, the purpose of this activity is to force a balance between the cash on hand and the record of cash received. In one fraud, for instance, a department manager altered and destroyed cash register tapes to help conceal a fraud scheme that had gone on for four years.

Destroying Register Tapes

If the fraudster cannot make the cash and the tape balance, the next best thing is to prevent others from computing the totals and discovering the imbalance. Employees who are stealing at the point of sale sometimes destroy detail tapes that might implicate them in a crime.

Preventing and Detecting Cash Larceny at the Point of Sale

Most cash larceny schemes only succeed because of a lack of internal controls. In order to prevent this form of fraud, organizations should enforce separation of duties in the cash receipts process and make sure there are independent checks over the receipting and recording of incoming cash.

When cash is received over the counter, the employee conducting the transaction should record each transaction. The transaction is generally recorded on a cash register or on a prenumbered receipt form. At the end of the business day, each salesperson should count the cash in his or her cash drawer and record the amount on a memorandum form.

Another employee then removes the register tape or other records of the transactions. This employee also counts the cash to make sure the total agrees with the salesperson’s count and with the register tape. By having an independent employee verify the cash count in each register or cash box at the end of each shift, an organization reduces the possibility of long-term losses resulting from cash theft. Cash larceny through the falsification of cash counts can be prevented by this control, and suspicions of fraud are immediately raised if sales records have been purposely destroyed.

Once the second employee has determined that the totals for the register tape and cash on hand reconcile, the cash should be taken directly to the cashier’s office. The register tape, memorandum form, and any other pertinent records of the day’s transactions are sent to the accounting department, where the totals are entered in the cash receipts journal.

Obviously, to detect cash larceny at the point of sale, the first key is to look for discrepancies between sales records and cash on hand. Large differences normally draw attention, but those who reconcile the two figures should also be alert to a high frequency of small-dollar occurrences. Fraudsters sometimes steal small amounts, hoping that they will not be noticed or will be too small to review. A pattern of small shortages may indicate the presence of this type of scheme.

Organizations should also periodically run reports showing the number of discounts, returns, adjustments, write-offs, and other concealing transactions issued by employee, department, and/or location. These transactions may be used to conceal cash larceny. Similarly, all journal entries to cash accounts could be scrutinized because these are often used to hide missing cash.

Larceny of Receivables

Not all cash larceny schemes occur at the point of sale. As discussed earlier, employees frequently steal incoming customer payments on accounts receivable. Generally, these schemes involve skimming—the perpetrator steals the payment but never records it. In some cases, however, the theft occurs after the payment has been recorded, which means it is classified as cash larceny. For example, an employee posted all records of customer payments to date but stole the money received. In a four-month period, this employee took over $200,000 in incoming payments. Consequently, the cash account was significantly out of balance, which led to discovery of the fraud. This case illustrates the central weakness of cash larceny schemes—the resulting imbalances in company accounts. In order for an employee to succeed at a cash larceny scheme, he or she must be able to hide the imbalances caused by the fraud. Larceny of receivables is generally concealed through one of the following three methods:

- Force balancing

- Reversing entries

- Destruction of records

Force Balancing

Those fraudsters who have total control of a company’s accounting system can overcome the problem of out-of-balance accounts. In another example, an employee stole customer payments and posted them to the accounts receivable journal in the same manner as the fraudster discussed in the prior case. As in the previous case, this employee’s fraud resulted in an imbalance in the victim company’s cash account. The difference between the two frauds is that the perpetrator in the first case had control over the company’s deposits and all its ledgers. She was therefore able to conceal her crime by force balancing: making unsupported entries in the company’s books that produced a fictitious balance between receipts and ledgers. This case illustrates how poor separation of duties can allow the perpetuation of a fraud that is ordinarily easy to detect.

Reversing Entries

In circumstances in which payments are stolen but nonetheless posted to the cash receipts journal, reversing entries can be used to balance the victim company’s accounts. For instance, an office manager stole approximately $75,000 in customer payments from her employer. Her method, in a number of these instances, was to post the payment to the customer’s account and then later reverse the entry on the books with unauthorized adjustments such as “courtesy discounts.”

Destruction of Records

A less elegant way to hide a crime is simply to destroy all records that might prove that the perpetrator has been stealing. Destroying records en masse does not prevent the victim company from realizing that it is being robbed, but it may help conceal the identity of the thief. A controller in one fraud used this “slash-and-burn” concealment strategy. The controller, who had complete control over the books of her employer, stole approximately $100,000. When it became evident that her superiors were suspicious of her activities, the perpetrator entered her office one night after work, stole all the cash on hand, destroyed all records, including her personnel file, and left town.

Cash Larceny from the Deposit

At some point in every revenue-generating business, someone must physically take the company’s currency and checks to the bank. This person or persons, literally holding the bag, has an opportunity to take a portion of the money prior to depositing it into the company’s accounts.

Typically, when a company receives cash, someone is assigned to tabulate the receipts, list the form of payment (currency or check), and prepare a deposit slip for the bank. Then another employee, preferably one who was not involved in the preparation of the deposit slip, takes the cash and deposits it in the bank. The person who made out the deposit generally retains one copy of the slip. This copy is matched to a receipted copy of the slip stamped by the bank when the deposit is made.

This procedure is designed to prevent theft of funds from the deposit, but thefts still occur, often because the process is not adhered to (see Figure 4-5). For instance, an employee in a small company was responsible for preparing and making the deposits, recording the deposits in the company’s books, and reconciling the bank statements. This employee took several thousand dollars from the company deposits and concealed it by making false entries in the books that corresponded to falsely prepared deposit slips.

FIGURE 4-5 Cash larceny from a deposit

Similarly, in a retail store where cash registers were not used, sales were recorded on prenumbered invoices. The controller of this organization was responsible for collecting cash receipts and making the bank deposits. This controller was also the only person who reconciled the totals on the prenumbered receipts to the bank deposit. Therefore, he was able to steal a portion of the deposit with the knowledge that the discrepancy between the deposit and the day’s receipts would not be detected.

Another oversight in procedure is failure to reconcile the bank copy of the deposit slip with the office copy. When persons making the deposit know that their company does not reconcile the two deposit slips, they can steal cash from the deposit on the way to the bank and alter the deposit slip so that it reflects a lesser amount. In some cases, sales records are also altered to match the diminished deposit.

When cash is stolen from the deposit, the receipted deposit slip is, of course, out of balance with the company’s copy of the deposit slip (unless the perpetrator also prepared the deposit). To correct this problem, some fraudsters alter the bank copy of the deposit slip after it has been validated. This brings the two copies back into balance. For example, an employee altered twenty-four deposit slips and validated bank receipts in the course of a year to conceal the theft of over $15,000. These documents were altered, with correction fluid or ballpoint pen, to match the company’s cash reports. Of course, cash having been stolen, the company’s book balance does not match its actual bank balance. If another employee regularly balances the checking account, this type of theft should be easily detected.

Another mistake that can be made in the deposit function, one that is a departure from common sense, is entrusting the deposit to the wrong person. For instance, a bookkeeper who had been employed for only one month was put in charge of making the deposit. She promptly diverted the funds to her own use. This is not to say that all new employees are untrustworthy, but it is advisable to have some sense of a person’s character before handing that person a bag full of money.

Still another common sense issue is the handling of the deposit on the way to the bank. Once prepared, the deposit should be immediately put in a safe place until it is taken to the bank. In a few of the cases we studied, the deposit was carelessly left unattended. In another fraud, for example, a part-time employee learned that it was the bookkeeper’s habit to leave the bank bag in her desk overnight before taking it to the bank the following morning. For approximately six months, this employee pilfered checks from the deposit and got away with it. He was able to endorse the checks at a local establishment, without using his own signature, in the name of the victim company. The owner of the check-cashing institution did not question the fact that this individual was cashing company checks; as a pastor of a sizable church in the community, the fraudster’s integrity was thought to be above reproach.

As with other cash larceny schemes, stealing from the company deposit can be rather difficult to conceal. In most cases, these schemes are successful for a long term only when the person who counts the cash also makes the deposit. In any other circumstance, the success of the scheme depends primarily on the inattentiveness of those charged with preparing and reconciling the deposit.

Deposit Lapping

One method that, in some cases, is successfully used to evade detection is lapping—when an employee steals a deposit on the first day and then replaces it with a deposit from day two. Day two’s deposit is replaced with one from day three and so on. The perpetrator is always one day behind, but, as long as no one demands an up-to-the-minute reconciliation of the deposits to the bank statement and if the size of the deposits does not drop precipitously, he or she may be able to avoid detection for some time. For example, a company officer stole cash receipts from the company deposit and withheld the deposit for awhile. Eventually, the deposit was made, and the missing cash was replaced with a check received at a later date.

Deposits in Transit

A final concealment strategy with stolen deposits is to carry the missing money as deposits in transit. In one instance, an employee was responsible for receiving collections, issuing receipts, posting transactions, reconciling accounts, and making deposits. Such a lack of separation of duties leaves a company extremely vulnerable to fraud. This employee took over $20,000 in collections from her employer over a five-month period. To hide her theft, the perpetrator carried the missing money as deposits in transit, meaning that the missing money would appear on the next month’s bank statement. Of course, it never did. The balance was carried for several months as a “deposit in transit,” until an auditor recognized the discrepancy and put a halt to the fraud.

Preventing and Detecting Cash Larceny from the Deposit

The most important factor in preventing cash larceny from the deposit is separating duties. Calculating daily receipts, preparing the deposit, delivering the deposit to the bank, and verifying the receipted deposit slip are duties that should be performed independently of one another. As long as this separation is maintained, shortages in the deposit should be quickly detected.

All incoming revenues should be delivered to a centralized department, where an itemized deposit slip is prepared, listing each individual check or money order, along with currency receipts. Itemizing the deposit slip is a key antifraud control. It enables the organization to track specific payments to the deposit and may help detect larceny, as well as lapping schemes and other forms of receivables skimming. It is very important that the person who prepares the deposit slip be separated from the duty of receiving and logging incoming payments, so that he or she can act as an independent check on these functions. Before it is sent to the bank, the deposit slip should be matched to the remittance list to ensure that all payments are accounted for.

Typically, the cashier delivers the deposit to the bank, and a cash-receipts clerk posts the total amount of receipts in the cash receipts journal. In some cases, the cashier does the posting, and a separate individual delivers the deposit. In either case, the duties of posting cash receipts and delivering the deposit should be separated. If a single person performs both functions, that individual can falsify the deposit slip and/or cash receipts postings to conceal larceny from the deposit.