15

Consulting, Litigation Support, and Expert Witnessing: Damages, Valuations, and Other Engagements

The modules, along with the learning objectives for this chapter include:

- Module 1 provides an overview of the types of engagements typically found in forensic accounting, as well as guidance on issues encountered in consulting, litigation support, and expert witness engagements. Module 1 has one overarching objective: To introduce the reader to the various types of forensic accounting engagements and the resources available to assist the professional in this area.

- Module 2 dives deeper into commercial damages, which typically require consideration of lost profits, as well as incremental revenues and expenses associated with generating lost profits. Two detailed examples are provided to help readers apply the concepts to hypothetical case facts. The goal of Module 2 is for readers to be able to articulate the essentials of commercial damages examinations, as well as apply those concepts to evidentiary material.

- Module 3 examines valuations. Valuations are used in a large number of engagement scenarios including commercial litigation. While valuation engagements focus on an examination of the underlying data and the application of appropriate interest rates, premiums and discounts, estimates of value can become complex. The learning outcomes for Module 3 include the ability to identify common techniques associated with valuations and apply those to case facts and circumstances.

- Module 4 considers losses associated with personal injury, wrongful death, and survival actions, sometimes referred to as forensic economics. Through discussion materials as well as a case example, Module 4 will walk readers through the various steps associated with the estimation of lost compensation, benefits, pensions, and household services. The objective of Module 4 is for the reader to be able to examine evidence associated with forensic economics cases and apply the appropriate techniques to simulated case data.

Module 1: Consulting, Litigation Support, and Expert Witnessing

Professional Standards and Guidance

The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) created the “Forensic and Valuation Services” (FVS) Section. This section, in concert with the efforts of the greater AICPA organization, has created several practice aids, special reports, and other publications to support the certified public accountants’ efforts with regard to litigation support and valuation engagements. However, the AICPA makes clear that a “practice aid” does not establish standards, preferred practices, methods, or approaches, nor is it to be used as a substitute for professional judgment. Other approaches, methodologies, procedures, and presentations may be appropriate in a particular matter because of the widely varying nature of the litigation services, as well as specific or unique facts about each client and engagement. Professionals involved in litigation support services are encouraged to consult with counsel about laws and local court requirements that may affect the general guidance contained in the practice aids.

As of this writing, AICPA special reports, practice aids, and other publications that address the concerns, issues, methodologies, and other aspects of litigation support, forensic accounting services, and valuations include the following:

- A CPA’s Guide to Family Law Services

- Assets Acquired to Be Used in Research and Development Activities

- Attaining Reasonable Certainty in Economic Damages Calculations

- Forensic and Valuation Services Practice Management Toolkit

- Business Valuations for Estate and Gift Tax Purposes

- Calculating Intellectual Property Infringement Damages

- Discount Rates, Risk, and Uncertainty in Economic Damages

- Engagement Letters for Litigation Services

- Forensic Accounting—Fraud Investigations

- Forensic and Valuation Services: Calculating Lost Profits

- Forensic and Valuation Services: Engagement Letters

- Forensic & Valuation Services: Related Standards

- FVS (Forensic and Valuation Services) Consulting Digest

- FVS (Forensic and Valuation Services) Eye On Fraud

- Introduction to Civil Litigation

- Measuring Damages Involving Individuals

- Mergers and Acquisitions Disputes

- Providing Bankruptcy and Reorganization Services, Volume 1—Litigation and Dispute Resolution in Bankruptcy

- Providing Bankruptcy and Reorganization Services, Volume 2—Valuation in Bankruptcy

- Serving as an Expert Witness or Consultant

- Testing Goodwill for Impairment

- Valuation of Privately-Held-Company Equity Securities Issued as Compensation

- VS (Valuation Services) Section 100 Toolkit

In the area of fraud examination, the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) offers the Fraud Examiners Manual, a virtual encyclopedia of information that addresses four major topics:

- Financial Transactions and Fraud Schemes

- Law

- Investigation

- Fraud Prevention and Deterrence

Further, the ACFE publishes Fraud Magazine and a wide range of antifraud resources that can be useful to the antifraud professional.

In the area of valuations, in addition to efforts by the AICPA, the National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA) provides textbook-like materials for education and training as well as courses and an examination that supports their Certified Valuation Analysts (CVA) credential.

The Journal of Forensic Economics, as well as several books on “forensic economics,” provide useful information on personal injury and wrongful death claims that often require the valuation of lost wages, fringe benefits, household services, and other losses.

Although these publications and their content are categorized as nonauthoritative, they provide useful information to practicing professionals. As fledgling fraud examiners and forensic accountants continue to develop their knowledge, skills, and abilities, these and other publications can be included in the professionals’ libraries and maintained among their important resources.

Engagement Issues and Professional Responsibility

Fraud examination, forensic accounting, and litigation support activities can expose the traditional professional to more risk than consulting engagements and, possibly, to more liability than traditional auditors. For example, professionals may be asked to evaluate business practices and transaction activities and are normally engaged by one side or the other—looking for “defense” of their client’s choices, decisions, and judgments while taking a critical view of the other side’s similar actions.

Professionals and their firms’ names may appear in the media and may even be accused of using less than professional approaches, turning a “blind eye” to their clients’ practices and activities; ignoring or not giving proper disclosure to important assumptions that constitute part of the engagement; as well as other professional shortcomings. Prior to entering into any litigation support, forensic accounting, or fraud examination activity, professionals are encouraged to consider the implications to their business reputation, professional stature, and possibly threats or personal harm or injury that may be attributable to their participation in the disputed issues. As with all engagements, professionals need to ensure that they currently have or can obtain the necessary skills, training, experience, and other resources required to participate in the resolution of the issues at hand.

An engagement letter is recommended for such work. If a written engagement letter is not provided, the scope of the engagement and other relevant information may be obtained as part of an oral arrangement. If the engagement is agreed upon through verbal discussions, the practicing professional should clearly note the discussion in memo format, paying particular attention to the wording used by the client or the client’s attorney.

The written engagement letter should describe the nature and extent of professional services to be provided. If the practicing professional is generating the engagement letter, the specialist should outline the degree of responsibility assumed and any limitations on liability. Importantly, any verbal or written understandings should not describe the expected outcomes of the work to be performed, make any guarantees regarding expected findings or results, and should not commit the practicing professional in any way to a particular position, opinion, or any aspect of the case that is grounded in judgment. That is the responsibility of the judge, jury, or other trier-of-fact. The engagement letter should make clear that the procedures and analyses to be performed in connection with the engagement do not constitute an audit, review, or attestation engagement as described in authoritative literature promulgated by the AICPA or PCAOB. It should also indicate that the engagement constitutes consulting services and is subject to applicable standards.

Practicing professionals, because of the nature of their independence and objectivity, generally, should not accept contingent fee arrangements. Instead, compensation should be based on hours worked and time spent on the engagements. The practicing professional may seek to obtain a retainer in advance. This simply helps ensure that the client has the ability to pay for the services rendered. If not paid in a timely manner, he or she may seek to suspend the engagement until money has been collected. Further, the professional may withhold the sharing of work product until the fees have been paid. But unpaid fees provide an opportunity for the opposite side and its counsel to attack the professional’s independence, judgment, and credibility. Opposing counsel may suggest that the arrangement is of a contingent fee engagement and that fees only be paid upon a favorable resolution for the client, even if this is untrue.

Fraud examination, litigation support, and forensic accounting activities can be staffed like any other engagement. Assistants and other professionals may be used to accomplish duties such as clerical tasks and sophisticated analyses; to conduct and document interviews; and to gather, compile, and analyze important books and records—financial, nonfinancial, and qualitative. However, the engaged professional is responsible for supervising the work performed by others, properly training assistants, and, ultimately, taking responsibility for all conclusions, judgments, decisions, and opinions.

Thus, although testifying professionals need not complete the work themselves, they are expected to be able to describe the nature, extent, and timing of all work performed. They must also be able to defend their conclusions, the outcomes, and their professional opinions. Given the adversarial nature of fraud examination, litigation support, and forensic accounting engagements, practicing professionals should expect their work product to be scrutinized closely, and they should be prepared to describe and defend all choices made.

Like the fraud examiner, the testifying expert should have no opinion concerning the ultimate outcome of the litigation. For practical reasons, the practicing professional is not an attorney, so he or she may not entirely understand or contemplate subtle nuances of the law. Similarly, forensic professionals may be working directly, indirectly, or tangentially with other experts whose areas of expertise may be unfamiliar to them. Thus, forensic accountants need to be careful of their reliance on the work of others. From a more professional perspective, the ultimate decision maker is the trier-of-fact—the judge, jury, or other person or body, saddled with the responsibility for deciding the case based on its merits from the evidence offered. The fraud examiner can have no opinion about the guilt or innocence of alleged fraudsters. Similarly, the fraud examiner or forensic accountant should have no opinion concerning the ultimate outcome of the dispute. This position is consistent with practitioners remaining unbiased and performing their work with impartiality. Thus, they do not act as advocates for a client or their allegations, assertions, or positions in a dispute.

Professional standards for expert witnessing do not require independence, as described in the AICPA, ACFE, NACVA, or other similar codes of conduct. However, depending on the nature of potential conflicts of interest and other issues of independence, opposing counsel may raise concerns over this to question a practicing professional’s credibility and objectivity. Further, although professional standards may not require independence, laws and regulations, such as the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002, may preclude some CPAs from performing litigation support and other similar consulting services under certain circumstances. General standards require professional competence, due professional care, proper engagement planning and supervision, and the collection and analysis of sufficient relevant data to support (provide a reasonable basis for) the conclusions and opinions offered.

Types of Consulting and Litigation Support Activities

Fraud examiners and forensic accountants can be engaged as consultants and experts to provide a wide array of services. First, not every engagement is related to litigation. But fraud examination and forensic accounting professionals get involved in many different aspects of issues that may someday be the subject of litigation. First, fraud examination is a methodology for resolving fraud allegations—from inception to disposition, including obtaining evidence, interviewing, writing reports, and testifying. However, fraud examiners, as designated by the ACFE, also assist in fraud prevention, deterrence, detection, investigation, and remediation. Thus they may be engaged to consult regarding indications or allegations of fraud, but also in any number of other areas. Similarly, CPAs may provide consulting services that are concerned with fraud but are not necessarily fraud examination services, auditing, or litigation support services. These might include the following1:

- Assessing the risk of fraud, noncompliance and illegal acts

- Evaluating the adequacy of internal control systems

- Substantive testing of transactions during an examination or a general consulting engagement

- Designing and implementing internal control policies and procedures

- Proactive fraud auditing when fraud is not suspected

- Preparing company codes of business ethics and conduct

- Consulting about employee bonding

- Developing corporate compliance programs

In litigation advisory services, accountants use their knowledge, skills, abilities, experience, training, and education to support legal actions; such activities are normally carried out by forensic accountants and fraud examiners acting as consultants, expert witnesses, masters, and special masters. Even though forensic accountants may provide litigation support services in criminal cases, the majority of them are in the area of civil litigation.2

Experts and expert witnesses are professionals who have been offered as such by parties to the litigation. However, the ultimate decision to qualify a witness as an expert is at the judge’s discretion, and the jury is the ultimate arbiter of credibility. Experts in the litigation advisory services context are expected to provide testimony, before a trier-of-fact, that includes their findings, conclusions, and opinions. Testimony may be provided in any number of venues, including federal, state, or local courts, depositions, regulatory hearings, arbitration, and mediation. Generally, the entire work product of the designated expert is discoverable by the other party. Work product includes not only the expert’s report and main analyses but also all notes, work papers, evidentiary materials collected as part of the case, supporting analyses, research, documents, and data reviewed or relied upon by the expert as part of their engagement. Drafts of reports, handwritten notes, and marginalia are all considered part of the expert witnesses’ work product. Thus, experts need to maintain careful vigilance over all aspects of their work and the impact that it can have on the parties to the litigation. That said, because the professional is not an advocate for one side or the other, the notes, marginalia, and draft reports should not typically be risky; however, they can give insight into how the professional developed conclusions and opinions, uncover any bias in performing the work and other procedures, and shed light on preliminary, but ultimately discarded, theories of the case that opposing counsel may find valuable to their side of the case.

Tools and Techniques: General Discussion

The term forensic is generally defined as used in or suitable to courts of law or public debate. When applied to fraud examination or forensic accounting, forensic has evolved to include procedures to gather evidence systematically, using investigative techniques such that the results derived from the procedures can be presented in a court of law or similar setting (arbitration, mediation, regulatory hearing, or other setting) where disputes are heard and resolved. Some of the various professional environments applicable to forensic engagements and fraud examination specifically associated with financial issues and disputes include accounting as well as the following:

- Auditing

- Fraud examination

- Law

- Sociology

- Psychology

- Criminal justice

- Intelligence

- Cyber security

- Computer forensics

- Computer data extraction and analysis, data mining, big data, data analytics

- Forensic sciences

In addition, most engagements are grounded in a specific industry, competitive environment, and/or business operational settings. Thus, the typical fraud examination, forensic accounting, or litigation support engagement usually requires the development of at least some knowledge of the business models, operational procedures, and other aspects unique to the organization and industry under examination. The purpose of the engagement is to utilize the various methodologies appropriate to the issue at hand, combined with research and investigative skills, to collect, analyze, and evaluate evidence and then to interpret it and communicate the outcomes. Not all engagements in this area constitute litigation support, because, as a practical matter, most engagements do not result in courtroom testimony. Nevertheless, all engagements require investigative tools and techniques to develop the most accurate and supportable conclusions and opinions. Therefore, the examination needs to be organized and structured to assist in the evaluation and interpretation of the evidence.

AICPA Practice Aid 07-1 describes seven forensic investigative techniques and compares and contrasts them with similar evidence gathering activities of auditors:

Public Document Reviews and Background Investigations

Public records include information about individuals, businesses, and organizations concerning the entity itself, as well as its owners, executives, managers, employees, related parties, and competitors. They may include real and personal property records, corporate and partnership records, criminal and civil litigation records, stock trading activities for public companies by executives, officers, board members, and managers, inheritance information, birth records, press releases, news reports, and other matters. Records may be evaluated as evidence in a case in many areas, such as opportunity, pressure, or motivation and rationalization, as well as evidence of the elements of fraud: the act, the concealment, or the conversion.

Keep in mind that the elements of fraud and the fraud triangle are often as valuable in litigation support activities as they are in fraud examinations. Although directly applicable to fraud examination, in litigation support engagements, evidence of opportunity, pressure, and incentives and rationalizations may be important in understanding the actions and motivations of the plaintiffs and defendants. Further, the act, concealment, and conversion provide a powerful investigative basis for evaluating the participation, intention and actions of a party to litigation.

Although most litigation stops short of fraud, the allegations made by one party against the other often mirror the issues associated with fraud allegations brought to fraud examination engagements. For example, a litigant involved in unethical and possibly fraudulent activities often attempts to conceal those nefarious or less desirable aspects of their actions. Evidence of activities to hide the questionable transactions and the underlying motivations of the litigants can be used to help judges and juries understand the intent behind those actions. Similarly, showing how the litigants benefited from their actions (conversion)—possibly at the expense of the other party—can help judges and juries understand the motives of litigants.

Although auditors rely heavily on documentation that supports transactions generated in the normal course of business, they typically do not often search public records. Auditors rely on documentation provided by clients, such as invoices, bank records, bank statements, etc. Some of those may be generated internally by the client; other documents may be solicited and obtained from third parties. The auditors tend to evaluate such records at face value. For example, an auditor often uses an invoice package to ensure that the transaction is properly reflected in the books and records of the client. Fraud examiners and forensic accountants often use public records to verify the existence of a vendor business—the vendor’s ownership, the vendor’s address and phone number—for comparison of similar phone numbers or addresses with those of employees. The fraud examiner or forensic accountant may go so far as to call the vendor to verify the contents and details of the invoice, to ensure the invoice’s authenticity and that the goods and services described therein agree with the books and records of the vendor, and that no other terms (e.g., off-invoice side agreements) or conditions are involved. Fraud examiners and forensic accountants may even visit the vendor locations to authenticate the books and records of the transactions of the company under examination.

Interviews of Knowledgeable Persons

The purpose of an interview is to gather testimonial evidence. Interviews are not normally conducted under oath, so they do not carry the same weight as testimony but are invaluable tools used by the fraud examiner and forensic accountant for gathering information. As discussed in a prior chapter, interviews have different goals, objectives, tools, and techniques than those of admission-seeking interrogations. Interviews are normally performed throughout the engagement to develop background information about the organization, the witnesses, and potential targets, as well as to help identify books, records, documentation, and other information that may be useful. In a litigation support context, the interview may be in the form of a deposition (under oath), and the counsel for whom the professional is working asks the questions.

In litigation-type engagements, forensic accountants and fraud examiners acting as consultants and experts generally do not conduct interrogations in order to obtain admissions of guilt. Such activities are better left to the attorneys involved in the case, because these involve specialized tools and techniques, and the admissibility of the outcomes often hinge upon following proper procedures to ensure that the rights of individuals have not been violated. For example, the person being interrogated may have the right to have his or her attorney present—a legal issue. Thus, fraud examiners and forensic accountants simply gather information from interviews with witnesses and potential targets.

Auditors interact verbally with clients through inquiry; in fact, these are extensive and an integral part of the audit process. They gather information about procedures, policies, and processes, as well as explanations for red flags, anomalies, client positions, and other client decisions. Audit personnel may inquire about unexpected account balance fluctuations, unanticipated results of transaction testing, the general condition of the business, changes to the client’s business model, internal control issues, standard operating procedures, and other matters deemed necessary by the audit team.

Further, all members of the audit team are expected to make inquiries of management, including the audit staff, senior accountants, managers, and partners. These outcomes may be documented as audit evidence or may be the launching point for further analytical procedures, substantive testing, or other work considered necessary. Traditionally, auditors have not been trained in interviewing and interrogation. In contrast, forensic accountants and fraud examiners, generally, have training in assessing both verbal and nonverbal responses and interviewee reactions that may lead the interviewer to conclude the possibility of deceptive or dishonest responses to the questions.

Confidential Sources of Information and Evidence

In some situations, witnesses may be willing to share their knowledge only under the condition that their identities remain confidential. Optimally, each organization has an anonymous tip hotline where employees, vendors, managers, suppliers, customers, and other stakeholders can provide information without divulging who they are. The challenge is that allegations need to be detailed enough so that their reliability may be judged in an efficient and nonintrusive manner. At least one organization dropped its use of the anonymous tip hotline for external stakeholders because the tips received were usually unsubstantiated personal vendettas rather than communication of important information. The “hidden motive” of the confidential source is a genuine risk to an examination, and all tips received anonymously should be carefully evaluated before concluding that the allegations are justified. Individuals with whom the alleged perpetrator had a previous relationship—former spouses, business partners, employees, neighbors, and friends—may have a hidden motive. The key is to be able to gather enough information from the confidential source, so that claims can be checked for authenticity, without creating undue suspicion on a potentially innocent person. In some cases, even though the tip may have been made anonymously, the provider may be discovered via a variety of issues, such as the type of information provided or where it was derived. Thus, in some cases, the anonymity of the tip provider may not be able to be protected.

Rather than use confidential sources, auditors tend to complete their work out in the open. However, generally accepted auditing standards require that auditors not only gather information from the company being audited but also collect evidence from third parties, usually in the form of confirmations. Auditors typically confirm transaction details, account balances, terms, and conditions of sales, as well as the existence of information not previously outlined in the documentation between the parties. A third party may be unwilling to sign a confirmation stating that “all terms and conditions are described in the confirmation” and that “no other terms and conditions exist” related to the transaction or account balance. Such a refusal should be a significant red flag.

In either case, the auditor, fraud examiner, or forensic accountant has a responsibility to assess the relevance and reliability of the information, whether received from third parties or confidential sources. The auditing or litigation support professional should look to other facts that either support or refute the information provided by individuals or outside entities. Such an approach allows the professional to either corroborate the claims made or disprove them because they do not appear to be supported by a preponderance of the evidence.

Laboratory Analysis of Physical and Electronic Evidence

Forensic accountants and fraud examiners tend to be suspicious about much of the information and data received. For example, in some cases, documents are not only subjected to confirmation with external transaction participants but also subjected to fingerprint analysis and procedures for forgery and/or fictitious or altered documents. Computer forensic specialists have the ability to image hard drives, search for hidden or deleted files and e-mail, as well as search the hard drive contents for various terms, conditions, numerical values, etc. Computer tools can also analyze multiple transactions to draw meaning, extract descriptive statistics, and examine manual and electronic (automatic) journal entries.

Observation is an integral part of all audits. Auditors observe the taking of physical inventories, recount inventories, recalculate account balances, and apply other procedures consistent with the objectives of observation and review of physical audit evidence. Although auditors generally consider that various types of audit evidence may be created or altered to support transactions and account balances, they tend to react more to aberrations, anomalies, and other issues that come to their attention. Although auditors should rely on their professional skepticism to guide their judgments regarding the authenticity of documentary and other evidence, they typically do not have training and experience to evaluate intentionally altered and manufactured documents. On the other hand, forensic accountants and fraud examiners tend to be more proactive in their search for evidence that corroborates or disputes the information and are more skeptical than auditors—almost always requiring some form of corroboration from multiple sources.

Forensic professionals understand that skilled fraudsters often manipulate the data provided by altering documents or limiting the amount and timing of data made available to the opposing side. Thus, forensic accountants and fraud examiners are more apt to rely on nonfinancial data as a corroboratory technique for evaluating data captured in the financial books and records. They also use data extraction and analysis techniques (e.g., data mining), big data, and forensic analytics to identify meaningful patterns, missing information, unusual items, and evidence of collusion and/or management override of the system of internal controls and procedures.

Physical and Electronic Surveillance

Law enforcement professionals engaged in white-collar crime investigations often conduct physical and electronic surveillance. Physical and video surveillance is permitted, but electronic audio evidence (capturing spoken words) requires court permission. The legal standard is the “reasonable expectation of privacy.” When in a public place, persons do not have that expectation, but when engaging in telephone conversations, they do. Forensic accountants and fraud examiners do not usually conduct physical, video, or electronic surveillance unless they have the training and experience required to protect them from physical harm and to capture evidence in a competent manner so it is likely to be admissible in court. Although fraud examiners and forensic accountants may not conduct this type of work, it is common for them to receive results from law enforcement professionals or licensed private investigators. They then incorporate the results of these reports as evidence into their fraud examination, litigation support, or forensic accounting engagement.

Auditors seldom use physical, video, and electronic surveillance as a means of developing audit evidence. Generally, notwithstanding physical inventory and fixed assets observations, auditors rely on the books, records, and documents of the auditees, confirmations and other interactions with third parties, and inquiries of management and other personnel. If audit engagement evidence suggests that nefarious activities are taking place, the auditor normally assumes that the predication threshold has been met and calls in other professionals, who are more qualified to use physical, video, and electronic surveillance to develop the appropriate evidence.

Undercover Operations

Undercover operations are another tool used primarily by law enforcement and sometimes by private investigators. The goal is that, by putting professionals in close proximity to alleged perpetrators, evidence that is not contained in documents and in other forms can be collected and preserved for use in the larger examination. The outcomes may lead to the location of important books and records, the identification of previously unknown business partners, bank accounts, assets, and information that may be useful to further an examination. Generally, neither the forensic accountant nor the fraud examiner has the knowledge, skills, or abilities to develop this type of evidence but may rely on the work of other professionals and incorporate their findings and results into their forensic or fraud examination. This type of technique requires the trust of the alleged perpetrator, which requires time to develop. Thus, undercover operations generally take a lot of time and require a lot of patience, as well as financial resources. The physical safety of the undercover personnel is also an important consideration. Normally, auditors do not have procedures analogous to undercover operations.

Analysis of Financial Transactions, Financial Performance, Financial Condition and Relevant Non-Financial Evidence

Forensic accountants and fraud examiners rely heavily on their analysis of numerical data and relationships in many forms and contexts, the effect on related account balances, and the presentation of such in the financial statements and related notes. What typically separates antifraud and forensic accounting professionals from auditors is their enhanced knowledge of fraud schemes, red flags, and relevant tools and techniques associated with a particular engagement. Fraud and forensic professionals also need to have a greater understanding of the probability of any particular unusual behavior occurring and its relative magnitude, given the surrounding facts, circumstances, type of business, the business model, geographic locale, and types of customers, vendors, suppliers, and employees. Armed with the knowledge of the type of schemes that are likely, the red flags such a scheme would generate, the most common attempts at concealment, and the need for conversion (benefit) from the activity, fraud examiners, or forensic accountants can target their interviews and other procedures in a manner that is likely to yield the best information in the most efficient and effective manner. Thus, the fraud or forensic professional uses a targeted approach whether the engagement is centered on proactive fraud auditing or reactions to fraud allegations or suspicions.

Although litigation support activities may not have risen to the point where one side or the other is claiming fraud, the very nature of the adversarial action suggests that at least one side, if not both, have acted in bad faith. These individuals may be separated into two categories: predators or accidental (situational) fraudsters. Predators usually have little concern for ethical conduct and tend to be more interested in their own benefit. The accidental or situational defendant in a lawsuit generally starts off with good intentions but, for various reasons, becomes less concerned about being ethical as time passes. Both types, even in a civil litigation context, face fraud triangle-type issues: pressures (incentives), opportunity, and rationalization. Most investigations of bad acts are centered on the act, the concealment of that act, and the conversion or benefit arising therefrom. Fraud examiners and forensic accountants understand these issues from the outset and orient their work to answer the questions who, what, when, where, how, and why in the context of the fraud triangle and the elements of fraud centered on the issues associated with the bad act.

The analysis of financial transactions and financial statements—vertical, horizontal, and ratio analysis—is central to the traditional audit. Auditors trace individual transactions through the books and records to their presentation and disclosure in the financial statements. They examine the accounts, transactions, and balances for management’s financial statement assertions—existence, valuation, completeness, rights and obligations, and presentation and disclosure. Auditors also incorporate financial, nonfinancial, and qualitative data into their audit work.

The primary difference between antifraud professionals and auditors is the relative degree of evidentiary support. Auditors are expected to maintain a degree of professional skepticism; however, they may consider evidence at face value. Generally, antifraud professionals require more extensive levels of corroboration, evaluated with close attention to reliability and validity, concepts covered previously in this book. It’s also common for forensic and antifraud professionals to attempt to triangulate—identify as many sources of evidence for examination and consider that evidence from many perspectives.

Fraud examiners and forensic accountants are more aware of the issues associated with concealment and thus often require additional evidence to be convinced about the existence, timing, and nature of a transaction, account balance, or amount presented and disclosed in the financial records. Auditors also work within the confines of “fairly presented” and “not materially misstated.” These characterizations limit the work of the auditor to those observed anomalies, red flags, and audit issues that are likely to have a material effect on the financial statements such that the financial statements may not be fairly presented.

Forensic accountants and fraud examiners are generally more concerned that an anomaly or two may actually just be the tip of the proverbial iceberg, and they are not likely to be satisfied until that anomaly has been considered from every angle and exhaustively examined. Auditors, on the other hand, generally, will not pursue those issues that are unlikely to be material, beyond putting specific anomalies to rest.

Tools and Techniques Discussed in Prior Chapters

The forensic accountant’s engagement, as outlined in this chapter, arises from a civil litigation claim, a valuation that needs to be developed, an employment (personal injury or wrongful death) issue, or some other issue that can make efficient and effective use of the professional’s skillset. Similar to fraud examinations, forensic accounting engagements are an iterative processes. First, an issue, an assertion, or numerous issues and assertions are observed or presented by a party to a dispute. Given a commitment to evidence-based decision making, the professional starts by an initial examination of those claims in the context of whatever preliminary evidence is available. Based on the initial review, a detailed listing of desired evidence is developed either independently, with the client or with an attorney. Armed with additional evidence, the professional digs deeper.

Examinations, in essence, are where evidence intersects with the tool and techniques of the antifraud and forensic accounting profession. During any given examination, the professional will select those tools and techniques he or she believes will be most applicable, accurate, and effective to resolve the allegations, assertions, and issues. These tools and techniques also are used to develop analyses and amounts to a reasonable degree of scientific certainty. From an examination perspective, tools and techniques discussed in prior chapters, related to targeted risk assessment, fraud detection, and the basics of forensic accounting and fraud examination are also important in the examination process. As such, the information described in prior chapters may be relevant to the material discussed in this chapter. In that regard, we offer the following chart that reviews common examination tools and techniques with a reference to their coverage in prior chapters and suggest that readers revisit that material because each may play a critical role in an examination, even though the technique is not discussed extensively in this chapter.

| FAFE Tool/Technique | Chapter |

| Analysis of cash flows and transactions | 7, 9 |

| Analysis of competing hypotheses (fraud theory approach) | 1, 9 |

| Analysis of nonaccounting and nonfinancial numbers and metrics | 1, 3, 7, 8, 9 |

| Analysis of related parties | 7 |

| Big data and data analytics | 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 |

| Consideration of analytical and accounting anomalies | 8, 14 |

| Consideration of red flags | 1, 2, 7, 8, 9, 14 |

| Consideration of the fraud triangle | 2 |

| Documents, including invoices, bank and credit card statements, investment statements, contracts | 9 |

| Email, textual analytics, social media | 9 |

| Financial statements, tax returns, indirect and ratio analysis | 3, 7, 9 |

| Internal controls, the control environment, and opportunity | 1, 8 |

| Interviewing for information and admissions | 1, 3, 10 |

| Moving money, money laundering, offshore accounts | 12 |

| Other tools and techniques | 9 |

| Use of graphical tools for analysis and communication | 1, 11 |

| Use of information technology and digital devices | 11, 13 |

These tools and techniques discussed in prior chapters, in the right circumstances, will be applied to evidence potentially associated with civil litigation, cases centered on operational and financial performance, valuation, and employment losses. Space limitations prevent repetitive coverage of material covered in other sections of this book.

Module 2: Commercial Damages

Commercial damages provide a challenge to the forensic accountant because the cases vary considerably. The tools and techniques that work in one case may not work in another. More diverse than the tools and techniques are the fact patterns, circumstances, available evidence, and types of issues that require resolution in the underlying dispute. In addition, the types of businesses and organizations and their related industries vary from one case to the next.

In each litigation support engagement, the forensic accountant must quickly get up to speed on key aspects of the business model, the industry, competition, operational performance, and financial profitability. Furthermore, the number of issues in dispute and the complexity of the case drive the amount of work required.

The ability to estimate damages is both an art and a science. The science comes from the understanding and appropriate use of proper accounting methods (i.e., generally accepted accounting principles or “GAAP”). The art comes from knowing how the accounting, financial, and nonfinancial information is used to create the required components of the damages estimate. The science is driven by the nature of the asserted damages, the complexity of the case, the underlying type of liability claimed, and other aspects. In some instances, the availability of data helps determine the types of analyses required. Critical thinking skills are as important in litigation support engagements as they are in detecting and investigating allegations of fraud.

At a basic level, the plaintiff and the defendant tell two different stories and have differing explanations for what happened (who, what, when, where, how, and why), using similar facts that have been entered into evidence. As such, some of the damage calculations are, at least, partially affected by the diverse perspectives. The forensic accountant as an independent, objective professional must examine the differing storylines and compare each side’s position to the evidence. Upon examination of the evidence, one or more stories, or critical aspects of the stories, generally will fail to be supported by the evidence. As such, a forensic accountant may find herself examining individual aspects or various assertions offered by the parties as a foundation for her opinion related to the overall damage claims. Often the evidence is in the form of deposition testimony of the fact witnesses and the professional opinions of other experts. Important to the forensic accountant’s case are the various elements of financial evidence gathered, usually by subpoenas traded by the opposing parties, but which also may be collected independently from publicly available sources, such as banks, independent appraisers, the Secretary of State’s office, etc.

In most damage and valuation litigation engagements, the forensic accountant is hired by one side or the other—the plaintiff or the defendant. The plaintiff usually seeks large damage awards, whereas the defendant generally tries to minimize any amounts associated with liability. Forensic professionals should be independent, objective, and unbiased and, as such, must prepare a defensible damage estimate. In most cases, attorneys prefer to know the estimated damages, even if that estimate is bad news for their client. Accurate, timely, and professional advice helps the attorney to formulate effective strategies for pursuing the case, including negotiated settlement, arbitration, mediation, or civil trial. Furthermore, recognizing that their reputation in the professional community is a valuable asset, no case is worth jeopardizing the professionals’ integrity.

Legal Framework for Damages

Generally, to successfully pursue a claim for legal damages, the allegedly injured party must prove two points:

- Liability: That the other party was responsible for all or part of the damages claimed

- Damages: That the injured party suffered certain losses as the result of the actions or lack of actions of the offending party

To prove that damages were sustained, the injured party also needs to prove three additional elements. First, that the accused party was the direct or proximate cause of the damages, by either causing or contributing to them as a result of their conduct. Second, the amount must be calculable to a reasonable degree of certainty. Third, the accused parties should have been reasonably able to foresee that damages were likely to accrue as a result of their conduct. Note that such conduct may include action or inaction either may lead to large damage awards.

Generally, damages result from a tort or breach of contract. With a tort, the action itself leads to direct harm. In breach of contract, the relationship between the parties was previously defined in an agreement, and the courts are asked to interpret that contract. Some cases involve millions of dollars and may hinge on a single word or phrase found within a contract of hundreds of pages. Some clauses that seem clear at the inception of a contract are later interpreted differently by the parties. In those cases where the parties cannot reach agreement, the courts are asked to settle the matter. Further, no contract can anticipate every contingency. Those aspects of the relationship between the parties that are not specified in the contract are subject to negotiation; if the parties cannot negotiate a reasonable basis for moving forward, they may choose to litigate the matter and let the courts decide.

Torts, on the other hand, occur when a party has been injured, even though the parties to the suit do not have a contractual relationship. Torts may include theft, fraud, infringement of trademarks, copyrights, trade secrets or other intellectual property, professional malpractice, defamation, or negligence.

Causality is central to the issue of damages. Even if the damages sustained by a plaintiff are substantial but the impact of the defendant’s actions cannot clearly and conclusively be associated with them, the plaintiff may not prevail in the action. The plaintiff’s goal is to connect the plaintiff’s conduct with the damages sustained. Plaintiffs may use graphics, such as timelines, or statistical methods to demonstrate the alleged causality between the defendant’s conduct and their harm.

Types of Commercial Damages

Successful plaintiffs may be awarded different types of damages:

- Compensatory

- Economic loss or restitution

- Lost wages

- Incremental or incidental expenses

- Lost profits

- Lost value

- Reliance

- Punitive

- Special

Compensatory damages are those amounts designed to compensate the injured party for some specific loss. Economic loss or restitution damages compensate for a specific loss and recognize that the damages carry into future periods. Reliance damages put the injured parties back where they would have been if the cause of action had not happened. Punitive damages are monetary awards that have the intention of punishing the defendant sufficiently to act as a financial deterrent, to discourage similar actions in the future. Finally, courts may award special damages to plaintiff or defendants.

The Loss Period

One of the first steps in measuring commercial damages is determining the loss period. For a breach of contract claim, it is generally the remaining term of the contract. However, exceptions are sometimes warranted. In some cases, a period other than the contract term is more appropriate:

- If the contract term is very long, courts may be reluctant to enforce it because of issues of uncertainty, especially in industries where contracts are altered prior to the completion of the full term.

- In other cases, the damages may extend beyond the contract term because the parties have a history of extending or renewing prior contracts.

Thus, although the contract period may appear to be the logical choice, the facts and circumstances may indicate that a different measurement period is more appropriate.

The measurement period for commercial damages related to torts can be more difficult because, unlike breach of contract claims, a preliminary starting point is not available. With torts, the loss period starts when the tort begins and ends when business returns to normal—either when revenues rebound or expenses decline to appropriate levels. The damage period for a tort can be considered closed, open, or infinite. It can be infinite when the damaged company has effectively been put out of business. In such cases, business operations and performance obviously can never return to normal. A closed period, on the other hand, is when there is a loss in sales or additional expenses during a time frame that can be reasonably defined, which has ended prior to the calculation of damages. An open period of damages indicates that, at the time of the forensic work, the damage period still exists and is expected to continue into the future.

Economic Framework for Damages

Commercial damages do not occur in a vacuum. The amount of loss may be affected by the general economy, the conditions of the industry, the damaged entity’s competitive environment, and other specific issues. In some cases, the damage assessment may be restricted to the organization without detailed, formal evaluation given to the economy, industry, and competition because their impact is judged negligible. Therefore, even if not formally documented, this may be an inherent assumption behind the work of the antifraud professional or forensic accountant.

The impact of the overall economy on the entity under study and on the particular types and amounts of damages being sought is the first step in documenting losses as a result of commercial liability—tort or breach of contract. The global and national economies are cyclical, usually either expanding or contracting. For the United States, one of the most prominent indicators of the national economy is the gross domestic product (GDP). The more GDP generated, the better the economy is. Although very large firms are often affected by global or national economic trends, smaller firms can also be affected by regional economic conditions. If need be, economic performance can be further localized by evaluating a state, city, county, town, or even, in some cases, at the neighborhood level. Although data on the global, national, and, in some cases, the regional economy tend to be gathered with regularity and made available to the public, economic indicators by state, city, county, town, or neighborhood vary considerably by the amount of data available and how long it takes to have these data collected, summarized, analyzed, and released to the public. Nevertheless, the fraud examiner and forensic accountant should give consideration to the appropriate economic conditions and available data as a starting point for any damage analysis.

Once the appropriate overall economic data have been identified, and the impact, if any, on the damage claim has been assessed, the next level of consideration is the industry—the number of organizations that offer similar products or services and possibly compete with one another for customers and market share. An industry assessment is based on the number of competitors, the degree of concentration, and the extent of vertical integration. Competition, combined with the overall economic conditions, often explains at least some portion of the organization’s performance and, thus, may be an integral part of the damages analysis. When the overall industry is growing and performing well, the average organization tends to perform in a similar manner. The condition of the industry and its growth can be assessed on numerous levels—sales and revenues, shipments to customers, employment levels, and other financial and nonfinancial dimensions.

The U.S. Department of Commerce tracks numerous statistics based on SIC (standard industrial classification) code. Further, companies such as First Research, Moody’s, Value-Line, and others provide periodic industrial performance metrics. Like the overall economic data, the applicability of the industry data to a firm-specific damage claim cannot be arbitrarily assumed. The firm subject to damages analysis may be on the fringes of the industry and have very little in common with it. At the other end of the spectrum, the industry may have few participants, and the company under study may be the largest participant and overall driver of industry performance. Thus, even though the company and industry data are highly correlated, industry analysis may yield little value.

Notwithstanding the appropriate means by which industry data should be incorporated into damage analysis, the industry should be examined for the damage period or left out for appropriate reasons. Related to the overall industry, when appropriate, the performance of the entity under study to its key competitors may be an important part. The damaged organization can be compared along the dimensions of economies of scale—critical supplier and customer relations, technological advantages and shortcomings, life cycle of the company and its products—that help the fraud examiner or forensic accountant to understand the organization’s situation.

Once the economic and industry data have been gathered and evaluated for applicability and assessed for impact on firm performance, the next step is to compare them to those of the firm under consideration. As a starting point, financial statement data should be gathered, including balance sheets to assess financial condition; income statements to assess operational performance; and cash flow statements to determine the sources and uses of cash; and the ability of the company to generate cash flows from operations, invest in the future of the organization, and examine choices for financing (obtaining debt and equity capitals and paying returns on that capital in the form of dividends and principal repayments).

Optimally, the financial statements should be collected on a monthly basis, but, in many cases, quarterly and annual financial data will suffice. In addition to financial statements, another important source can be tax returns. They not only show the taxable income and other information provided to the Internal Revenue Service, but the return also has an annual balance sheet and a reconciliation of book to tax income. Another important source of data to assess commercial damage amounts is subsidiary, regional, divisional, product line, and other financial statement data breakdowns. In many cases, the alleged liability (the cause of the damages) affects only a portion of the business, and such internal breakdowns allow for a more fine-tuned analysis and estimation of damages.

Finally, nonfinancial data are often very important for developing and evaluating the reasonableness of damage claims. Although it is not always available, the ability to break the financial statement numbers into prices and quantities can be valuable. In some cases, nonfinancial data (volumes or quantities) may allow the data to be broken into prices and quantities. Then, each element can be considered independently and in concert with an effort to develop and evaluate damages.

Other important considerations can be the historical performance and financial conditions; rates of growth (historical and projected); sales data; and sales by product-line, key customers, regions, and divisions. Fraud and forensic accounting professionals understand that, for financial statements, the account balances and the accounting for specific transactions and groups of transactions—such as accounts receivable—are often affected by the numerous discretionary choices made by accountants or management. Executives and managers make choices about the applicability of specific, generally accepted accounting principles; the discretionary aspects of applying them; the necessity of using estimated and other judgments to determine the amounts reflected in the books and records; and the impact of unusual, one-time (nonrecurring) transactions.

These discretionary aspects are available so that financial managers and executives can make choices that best reflect the overall economic performance of the business. These can also be used for less than desirable goals, such as managing earnings and hitting one-time performance goals and objectives. Unfortunately, they also may present the opportunity for collusion and management override of internal controls—to record fictitious journal entries; develop unsupportable accounting judgments and estimates; and record unusual, one-time events that do not reflect the economics of the underlying transactions. Such manipulations may be systemic and embedded in the processes that have an impact on regularly recorded transaction amounts.

Using the financial and nonfinancial data collected, one of the most common firm-specific assessments is ratio analysis. Ratios may be categorized as liquidity, profitability, efficiency, or capital structure ratios. The categories, specified in AICPA Practice Aid 06-3, Analyzing Financial Ratios, include the following:

- Liquidity ratios

- Current ratio

- Quick ratio

- Working capital

- Inventory to working capital

- Current assets turnover

- Inventory to current liabilities

- Profitability ratios

- Gross profit percentages

- Operating profit percentages

- Net income before taxes (NIBT) percentage

- Net income after taxes (NIAT) percentage

- Return on equity

- Return on assets

- Efficiency ratios

- Accounts receivable turnover

- Accounts receivable collection period

- Inventory turnover

- Inventory to days in inventory

- Operating cycle

- Accounts payable turnover

- Accounts payable days outstanding

- Asset turnover

- Net revenue to working capital turnover

- Net fixed assets to stockholder’s equity

- Capital structure ratios

- Debt to equity

- Current debt to equity

- Operating funds to current portion of long-term debt

- Times interest earned

- Long-term debt to equity

In addition, the growth in sales and revenues, accounts receivable, inventory, and accounts payable should approximately align with one another. If not, one should investigate the reasons.

Finally, an assessment of cash flows can also be useful. First, operating cash flows should be positive (i.e., meaning that the company is generating cash flows from operations). Maybe more importantly, cash flows from operations should generally be greater than operating income because of the add-back of depreciation and other noncash expenses to income (assuming that the indirect method is used to create the statement of cash flows). Normally, cash flows from investing transactions should be negative, indicating that the company is investing in its future. Whether these dollars have been targeted to the appropriate long-term assets is a qualitative assessment that must be made. But it does not negate the expectation that investing cash flows be negative (for companies in growth and development stages).

Finally, financing cash flows can have either a positive or negative sign. Financing cash flows being positive suggests that equity and/or debt investors believe in the future of the company, and it also may indicate that the company will be expanding. Likewise, negative financing cash flows can be associated with dividend payments and debt repayments. Qualitative assessments are required to determine whether the financing cash flows reflect preliminary signs of positive or deteriorating financial condition. Each of these assessments can be compared to industry norms, those of key competitors, and those of the organization over time.

Quantifying Lost Revenues and Increased Expenses

The accepted concept for measuring lost revenues, excess expenses, and/or lost profits is to project these incremental changes over a loss period. Essentially, the lost revenues are those that the damaged entity could have expected except for the actions of the adversarial party. Similarly, incremental expenses are those additional expenses incurred as a result of the actions of the adversarial party. A number of methods can be used to develop incremental lost sales or excess expenses; some of those are discussed in the following paragraphs. Notwithstanding the choice of methodology, the forensic accountant has two competing goals: a high degree of accuracy and simplicity.

The value of simplicity is that proving the foundations for the claim is relatively straightforward and it is likely that the other side—the judge and the jury—will be able to understand the method and calculations. However, a risk in using simplified methods is that they may be subject to attack, because they may oversimplify the estimate of damages and, thus, not meet the threshold of being provable with a reasonable degree of scientific certainty. More sophisticated methodologies may be more complete and accurate, but they risk being complicated and difficult to communicate or for the untrained to understand.

Even if the trier-of-fact or other parties understand the methodologies and their inherent subtleties, they may not give the method the credibility it deserves, which could affect the outcome of the court action. The forensic accountant is left with the goal of trying to measure the damages in the most accurate, yet simple method, recognizing the threshold of a reasonable degree of scientific certainty.

Some of the decisions that need to be made include:

- The base amount of revenues or expenses, usually based on historical experience or reliable projections

- The choice of revenue or expense growth rates, recognizing that influences outside the control of the company (e.g., inflation, seasonality, prior forecasting accuracy for the industry, competition, or the organization under examination) have at least some impact on expected rates over time

- Whether historical rates of growth are applicable to the damage period

- Whether relatively straightforward calculations (using a spreadsheet tool, such as Excel) are reasonable or whether more sophisticated methods, such as regression, statistical, or econometric methods, are better suited.

Regardless of what choices are made, every method and calculation inherently incorporates certain assumptions and relies on the judgment of the professional. Ultimately, the decisions need to be described and outlined in oral or written reports and defended during a deposition or in court. As such, the professionals need to ask themselves: “Do the outcomes make sense?” Sometimes, damage estimates appear perfectly reasonable and defensible on the surface, but, when examined more closely, they do not hold up under detailed scrutiny of the evidence.

For example, consider the damage claim where a supplier—one of many, to a reseller—makes a damage claim that asserts they were not given credit for units supplied by them to the reseller, and the undercredited units total more than the company sold in its entirely. The damage claim makes no sense, because it claims more units than the company sold, not recognizing that the allegedly damaged supplier provided no more than 5% of the total units available for sale. When carefully examined, the damage claim fails in light of a complete examination of the evidence; even though a forensic professional may have used sound methods and seemingly reasonable assumptions but failed to take a step back to look at the bigger picture from different angles and perspectives. With revenues, the forensic accountant must consider whether the organization has the infrastructure (operating capacity, fixed assets in place, a competent work force, intellectual horsepower, etc.) to meet the demands of the customers. If additional investment in infrastructure is required, incremental costs need to be deducted from projected lost sales.

Nonfinancial information, data obtained from independent third parties, evidence from nonaccounting, operational systems can all be informative in estimating lost sales, incremental expenses, and lost profits. These sources often provide relevant quantities or volume of activities, the “q” in the price times quantities calculation. Prices, while inherently financial, also permit the calculation of quantities or volume associated with revenue or expense amounts. Like other aspects of forensic accounting and fraud examination, a more granular examination of quantities and prices may permit a more thorough analysis of the revenue and expense amounts. The information regarding prices and quantities during the relevant period needs to be established to be credible. For example, invigilation considers activity before, during, and after an alleged act. The correlation between quantities and/or prices needs to be established for the “before” and “after” periods in order to have relevance for the “during” period. That said, nonfinancial evidence can be valuable and integral when using the following methods.

Some of the methods that can be used to develop estimates of lost sales, incremental expenses, and lost profits include:

The Before and After Method

This compares sales and expenses before the actions or inactions of the adversarial party to those same financial statement line items after the action or inaction of the defendant. The method assumes that the actions or inactions of the opposing party had a direct impact on these line items and that, “but for” those, the results before would have been achievable. Because this method considers the historical amounts in the books and records as a basis for estimating lost sales or incremental expenses, it is not subject to as much dispute as some other methods. That said, fraud examiners or forensic accountants should consider other factors that could have effects on the “after” performance of the entity. At a minimum, professionals need to be able to defend their theory.

The Benchmark (“Yardstick”) Method

This method assumes that some data exist that can be used to demonstrate how the revenues, expenses, and/or profits related to the liability claim for the loss period would have performed “but for” the actions, or lack thereof, of the adversarial party. According to AICPA Practice Aid 06-4, “Calculating Lost Profits,” typical benchmarks may include the following:

- The performance of the plaintiff at different locations

- The plaintiff’s actual experience, versus budgeted results from prior periods

- The actual experience of a similar business unaffected by the defendant’s actions

- Comparable experience and projections by nonparties

- Industry averages

- Prelitigation projections

- Profits realized by the defendant as a result of his or her actions related to the disputed revenues or incremental expenses. (An alternative way of looking at this is that the defendant, assuming a guilty verdict, may be required to disgorge wrongly obtained profits.)

Determining Lost Profits

Although the liability claim alleged by the plaintiff against the defendant is often centered on lost revenues and/or incremental expenses, the actual amount of damages is a function of lost profits. Thus, any incremental lost revenues or incurred expenses require additional evaluation that considers the impact on “bottom-line” net income or some appropriate derivation (e.g., cash flows) for at least a couple of reasons. First, from a practical perspective, in order to generate incremental revenues, most companies incur at least some incremental expenses. In order for the best estimate to be developed, incremental costs, expenses, and infrastructure (capacity) need to be subtracted from the incremental revenues. Second, the damaged party has a duty to mitigate its damages. As such, this obligation may result in incremental revenues from other sources, for example. Conversely, the generation of other sources of revenue or reduction of some expenses might mitigate losses.

For example, assume that a farmer loses a contract to provide corn to a distributor, and, as a result of market oversupply, no other distributors are willing to buy corn from the farmer. Assume also that the field is in a condition to grow a substitute crop—such as soybeans. As such, the farmer is obligated to do so, even if the soybean contract is less profitable than that for corn. In this circumstance, the best estimate of damages assumes lost profits related to the loss of corn sales, reduced by the benefits of reasonable steps (e.g., the planting of soybeans) to mitigate the losses, whether or not such steps were actually taken.

One might assume that gross profit is a good starting point for determining incremental profits. However, the portion of gross profit attributed to the cost of goods sold may include some fixed costs, particularly if the damaged party is a manufacturer, and the assumption that all cost of goods sold is a variable (incremental) cost may be erroneous. Further, in addition to variable/incremental costs incorporated in gross profit, other expenses related to selling and distributing may also be incremental.

For example, many companies generate incremental sales through advertising and marketing campaigns. Likewise, salespersons often receive commissions based on actual sales and hitting various levels of sales volume. Other costs, such as incremental labor, shipping, administration, and miscellaneous expenses, may be incurred to generate the incremental sales. There may also be cases where incremental revenues have zero associated incremental costs. An example of this is where the company was not given proper credit for sales by a distributor, but the company had, in fact, provided those incremental goods and services and thus had incurred incremental costs. In such a case, the damage claim is the amount of sales that were not credited to the plaintiff and excludes associated variable costs.

The definition of lost profits needs to be explored as well. Most commercial damage claims assume lost profits—incremental revenues less incremental expenses—and other costs required to generate the lost sales. However, AICPA Practice Aid No. 7, “Litigation Services,” indicates that losses can be characterized using a number of metrics, including lost profits, lost value, lost cash flows, net revenue, and incremental costs. The forensic accountant needs to evaluate which of these metrics or some other is best suited to measure the damages applicable to the case, facts, and circumstances at hand.

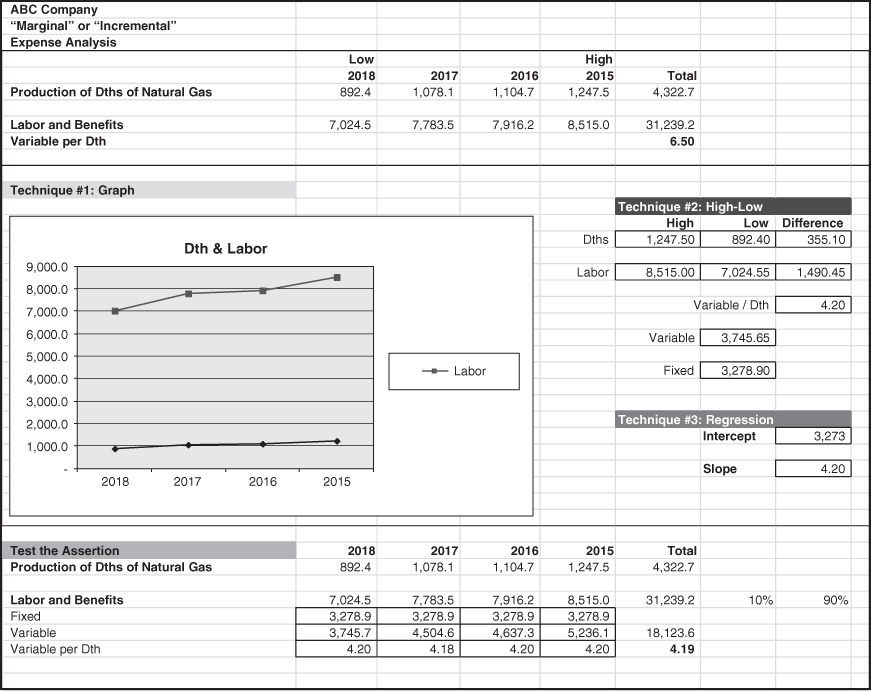

Determining Incremental Costs

Although incremental revenues can be determined using the methodologies discussed previously, properly isolating incremental costs and expenses can be trickier. Incremental costs are defined as those incurred as a result of the plaintiff’s action or inaction that would otherwise not be incurred (a type of damages) and those additional costs required in order to realize the projections of incremental lost revenues. First, as discussed previously, incremental costs associated with revenues may include infrastructure requirements, in order for the plaintiff to have the capacity necessary. Thus, some incremental costs are not those normally considered expenses associated with GAAP. Second, as a starting point, in order to isolate incremental expenses, the antifraud professional or forensic accountant needs to be able to identify the type of cost.

At the most basic level, cost behavior can be described as fixed or variable. Fixed costs are those that do not change with the level of output (e.g., sales). In contrast, variable costs are those that move directly with output, such as sales. A few concepts need to be further discussed. First, when analyzing fixed costs, many make the mistake of assuming that fixed costs exist at zero output. The assumption is that, when the producing unit is completely inactive or shut down, fixed costs exist. Although that assessment of fixed costs is valid, most organizations do not operate at zero output levels. More organizations operate in some range of volume called the “relevant range.”

Cost behavior should not be evaluated at zero production levels unless the levels are part of the relevant range. Zero production levels may be appropriate if one organization, the plaintiff, was put out of business by the defendant. In such a case, the relevant range may be zero units. However, assuming that the company produced 100,000 units but expected to produce (and sell) 110,000 units “but for” the actions of the defendant, the relevant range may be between 100,000 and 110,000 units. It is the behavior of costs in this range, fixed and variable, that are appropriate for analytical purposes.

Further, some costs exhibit semi-fixed, semi-variable, or mixed behavior. Take for example the output of one unit of labor (e.g., one incremental employee or one shift of workers). That unit has an ability or potential to produce some level of output, such as 20,000 tons of coal per day. If this unit is currently producing only 7,500 tons, the cost is fixed until the unit produces an incremental 12,500 tons per day. Once the incremental output reaches 20,000 tons of coal per day, in order to reach beyond those 20,000 units, incremental costs must be incurred. Those costs could include overtime, additional labor, or more shifts. Thus, for example, if the relevant range for consideration in a damage claim is 5,000 to 30,000 incremental units, this cost behaves in a semi-variable manner—because the relevant range spans the range where incremental costs are required = 20,000 unit. The cost is fixed for some time (up to 30,000 units); once the output unit crosses the threshold of 30,000 units/day, the variable nature of the cost kicks in, and additional expense must be incurred.

A second example is related to computer servers. Each can house and process only so much data for any given period of time. Until the computer server reaches capacity, no incremental costs are required, and the cost is fixed. However, once it reaches capacity, another computer server must be added, and the cost becomes variable or incremental and relevant to the damage estimate. In a similar manner, the computer server might require periodic software patches, maintenance, and updates. These aspects are variable. Unfortunately, in the world in which we operate, most costs tend to be mixed, semi-variable, or semi-fixed; thus, careful analysis of cost behavior is required.

The fixed and variable nature of cost behavior may also change with time; a cost that is initially fixed may become variable, and vice versa. For example, an organization may own computer equipment for some time and then switch to a leasing arrangement where the costs are associated directly with volume of use. Thus, the forensic accountant needs to analyze costs carefully in his or her effort to identify incremental increases.

Other concerns that must be considered include the following:

- Allocated costs. Not all costs can be directly associated with the activities that drive it. Other costs, such as administration and management, are often indirectly associated with units of output. In many cases, to derive a sense of profitability by product, by product line, by segment, by division, etc., the organization allocates those costs not specifically identifiable with the units of output. These must be carefully analyzed to ensure that the basis is reasonable and defendable and that the true incremental costs have been isolated and allocated. Costs at the unit level can easily be evaluated as to their incremental nature, but those occurring at the batch level, production level, facility level, or back-office administrative level are far more difficult to isolate.

- Accounting estimates. A significant number of GAAP expenses require estimates. Examples include bad debts, warranty costs, returns, and allowances, etc. In addition, at period end, in order to determine profitability, accountants attempt to get revenues in the appropriate period based on the revenue recognition principle, and they try to match expenses against revenues using the matching principle. Getting revenues and expenses in the right period also requires assumptions and estimates by the accountant. These judgments can have a significant impact on incremental revenue and expense calculation and should be carefully studied.

The methods for determining cost behavior include the following:

- Account analysis

- High to low method

- Graphics

- Statistical (regression, survey, and sampling)

- Engineering