CHAPTER 3

We can choose what we value

The hierarchy of values.

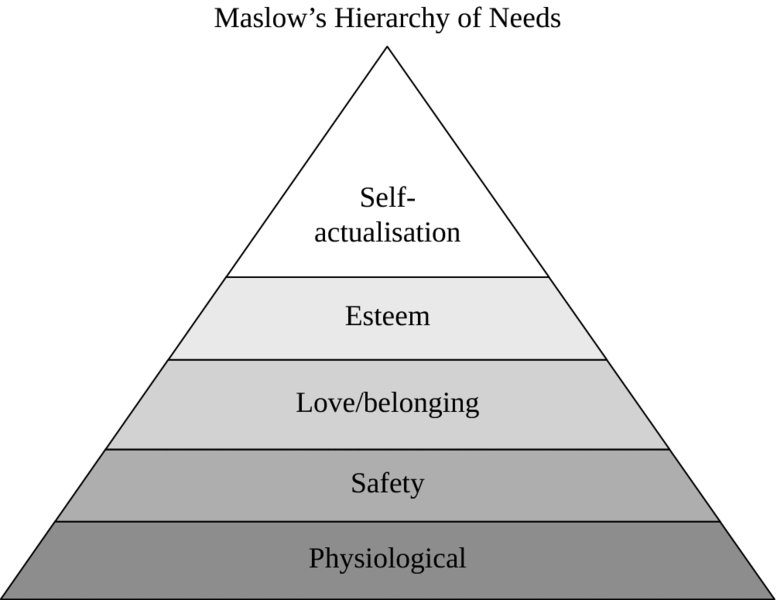

In 1943 a psychologist by the name of Abraham Maslow, in a paper titled ‘A Theory of Human Motivation’, proposed his famous hierarchy of needs pyramid, which is still quite well known today. He asked the questions, What motivates people? What makes people value what they do? What drives humans to value things like security, comfort, belonging, status, esteem or freedom? Maslow believed that people were motivated by what they valued at any one time, and proposed that what they valued in turn depended on what needs they had already met. Maslow split our needs into a series of levels that transition from what he called ‘lower order’ needs to ‘higher order’ needs. According to Maslow, a person has to satisfy basic physiological needs such as the need for food and water or sleep before they can value or be motivated to pursue other things. Once fed and rested, he said, we tend to value safety, security, employment and health. Then, if those needs are met, we can start to care about our position in the group: valuing love and belonging, seeking out friendships and connections. Only after meeting those needs do we start to value meeting higher level needs, such as self-esteem and confidence, and further self-actualisation, including creativity, spontaneity, problem solving and so on. So is what we value determined for us by our environment? By needs we have or haven’t met? Do we need to ensure that physical needs such as satiation, safety and security are met before we can hope to reach for something more? There was some precedent for what Maslow was proposing in works by earlier thinkers. The French philosopher Michel de Montaigne lived in the 16th century. While Montaigne’s father was a soldier, his great-grandfather, Ramon Felipe Eyquem, had made the family fortune as a herring merchant and as a result Montaigne grew up with the finest education available in the classics. But where the early Greek and Roman thinkers — who gave us the scientific method — praised the human ability to think rationally to overcome our circumstances, Montaigne disagreed. He placed an unusual focus on the human body and its effect on our supposed rational minds. Montaigne reminded us that we are all animals, and that it is pretty hard to think lofty thoughts when your stomach is empty, or your bladder is full (giving Maslow a precedent for his ideas about the primacy of lower order needs). The observation that family wealth often lasts only three generations seems to support Maslow’s hierarchy too. In chapter 2 we saw that those wealthy immigrant parents who perhaps were very focused on safety and security — to the point where they never felt they could accumulate enough — often encouraged their kids to value different things from what they did. But could the environment they provide be responsible for the change in values from one generation to the next? The wealthy parents raised children who never knew the hardships of their parents and had every material need taken care of. Perhaps being freed from the need to worry about survival or security would cause them to seek out status — a higher need in Maslow’s pyramid — thereby preserving the family’s wealth; but rather than growing it, they become more concerned with legitimising it. The children of a family that got rich in the plumbing business may go on to become doctors. In turn, their children — born with both security and status needs met — focus instead on pleasure or self-actualisation, and the wealth of the family and how it was created is forgotten. So are we trapped, only being able to value higher needs in life after all our basic needs are met? Fortunately not. Testing the hierarchy The rigidity of Maslow’s hierarchy was broken in what is possibly the cutest and saddest psychology experiment to date. Psychologists Harry and Margaret Harlow set out to investigate attachment theory, which asks: What makes an infant attach to its mother? Is it the need for food, a basic biological need or something else? They used orphaned infant monkeys who had been separated from their mothers at birth to test this. These sad little monkeys were given a choice: would they rather go to a surrogate dummy ‘mother’ that was shaped out of chicken wire, but had a bottle of milk attached to her, or would they choose a second surrogate mother that, instead of being made of cold chicken wire, was made out of cloth and fur, but had no milk to offer? The baby monkeys chose the ‘mother’ that was made out of fur — despite her lack of milk, and despite their hunger. Their hunger for comfort and love overrode their desire for basic sustenance. Subconscious needs higher up Maslow’s pyramid were being valued despite lower level objective physiological needs not being met. Although Maslow’s pyramid has remained popular, he formed his hierarchy of needs long before we really started thinking evolutionarily about our psychology. Later researchers have pointed out that we don’t stick to a strict progression from one level to another, although it can sometimes seem like we do. Despite all our supposed progress, we as a society are still focused on security. All it takes is a little fearmongering and we seem to be easily convinced to give up our freedoms in the name of a little more security. It’s clear that we don’t adhere to a strict hierarchical progression when meeting other needs as well. The middle of Maslow’s pyramid concerns the need for connection, attention and belonging. Social networks like Facebook are making it easier than ever before to connect with other people, so in theory we should all be free from these particular needs, able to pursue needs at a higher level. Yet Facebook, YouTube and Twitter — which should be meeting our needs for connection, approval and attention — only seem to be inflaming them. We seem more desperate for attention than ever before! But that’s the good news. We don’t have to wait until every lower need is met before we reach for higher levels, meaning we can unlock the creative energy that can produce the abundance that enriches us all. We know that we can choose to value or pursue higher level needs before meeting every lower level need. And yet the advice we are still being given hasn’t changed: if you want to get financially free, don’t focus on the higher level need for freedom or self-actualisation. First you must get secure. Spending your life pursuing security in the hope of winding up with freedom is insane. Matthew Klan People have speculated before that if we could just tip Maslow’s pyramid upside down — if we could start by valuing the things on the higher levels of his pyramid — then we could meet lower level needs simultaneously … What should you choose to value more if you want to become rich? Maslow may have been a little off in his understanding of what motivates us, but he got a lot of people thinking about the order or hierarchy of what we value. And that’s a good thing because while we may not have a hierarchy of needs, we do have what I call a hierarchy of values. What do I mean by ‘hierarchy of values’? Simply that our values compete with each other. At any one time, one thing you value will take precedence over another. In the conscious mind, the difficulty we have in holding two competing ideas at once is called cognitive dissonance. Not many people can handle it. The subconscious mind is even more primitive. It’s impossible to be elated and depressed at the same time. You can be one, then the other. But you can’t be both simultaneously. It’s the same with subconscious desires. One desire will take precedence. You can value freedom, then security; or security, then freedom, for example. So your values compete with each other and form a hierarchy, but the order is not set because you can choose what you value most. And although what you value can be influenced by your parents or by your upbringing, there are many other things that can influence what you value too. Your environment, heredity, the personality you are born with, how you earn money and the stage of life you are at can all influence what you value most at any one time. In fact, it’s this last point that I find particularly sad about the post-GFC economy. A whole generation of kids who are finding it so hard to enter the job market are missing out on a critical time in their lives. Most people don’t tend to value one particular thing their whole lives — at different stages we value different things — but the one time in most people’s lives when they really do value freedom, however briefly, is when they reach their late teens and have the urge to be free, to get away from their parents and start a new life. Instead, we have a generation now that quite rationally are staying in the family home, sometimes for years, and possibly missing the one time in their lives where it is easiest to strike out on their own, take risks and be free. So, despite all these outside influences that shape what we value, and the fact that most people will change to an extent what they value most over time, some people do seem to develop one particular value that they hold dear throughout their lives. What can they teach us about becoming rich? A Quick Recap You can’t value two things simultaneously. At any one time one value will take precedence over others, but your hierarchy of values can change. You can choose what to value.

Turning the pyramid on its head

Hierarchy of values