Individual Employee Incentive Plans

Learning Objective 1

Discuss the main incentives for individual employees.

Frederick Taylor popularized financial incentives—financial rewards paid to workers whose production exceeds some predetermined standard—in the late 1800s. As a supervisor at the Midvale Steel Company, Taylor was concerned with what he called “systematic soldiering”—the tendency of employees to produce at the minimum acceptable level. Some workers then had the energy to run home and work on their houses after a 12-hour day. Taylor knew that if he could harness this energy at work, Midvale would be much more productive. Productivity “is the ratio of outputs (goods and services) divided by the inputs (resources such as labor and capital).” 1 In pursuing higher productivity, Taylor turned to devising improved financial incentives.

Today’s employers use many incentives. All incentive plans are pay-for-performance plans because they tie workers’ pay to performance. 2 Variable pay usually means incentive plans that tie a group’s pay to company profitability (although some experts use variable pay to include incentive plans for individual employees); 3 profit-sharing plans are one example.

Individual Incentive Plans: Piecework Plans

Piecework is the oldest and most popular individual incentive plan. Here you pay the worker a sum (called a piece rate) for each unit he or she produces. (Of course, the worker must make at least the minimum wage, so the plan should guarantee at least that.) The crucial issue is the production standard. Industrial engineers often set this—for instance, in terms of a standard number of units per hour. But in practice, most employers set the piece rates more informally.

Straight piecework entails a strict proportionality between results and rewards regardless of output. The standard hour plan allows for sharing exceptional productivity gains between employer and worker; here the worker receives extra income (such as more per piece) for some above-normal production. 4

Incentives and the Law

There are legal considerations with piecework and other incentive plans. For example, under the Fair Labor Standards Act, if the incentive is in the form of a prize or cash award, the employer generally must include the value of that award when calculating the worker’s overtime pay for that pay period. 5 Suppose an employee who earns $10 per hour for 40 hours also got an incentive payment of $60 last week. Then his actual hourly pay last week was $460/40 or $11.50 per hour. If so, the employee would have to be paid one-and-one-half times $11.50 (not times $10) for any overtime hours worked.

Certain bonuses are excludable from overtime pay calculations. For example, discretionary Christmas and gift bonuses that are not based on hours worked, or are so substantial that employees don’t consider them a part of their wages, do not have to be included.

Merit Pay as an Incentive

Merit pay, or a merit raise, is any salary increase the firm awards to an individual employee based on his or her individual performance. It is different from a bonus in that it usually becomes part of the employee’s base salary, whereas a bonus is a one-time payment. The term merit pay is more often used for white-collar employees, particularly professional, office, and clerical employees.

Merit pay is the subject of much debate. Advocates argue that just awarding pay raises across the board (without regard to individual merit) may actually detract from performance, by showing employees they’ll be rewarded regardless of their performance. Detractors argue, for instance, that because many appraisals are unfair, so too is the merit pay you base them on. 6 Merit plan effectiveness depends on differentiating among employees. Base pay increases by U.S. employers for their highest-ranked employees recently were 5.6%, compared with only 0.6% for the lowest-rated employees. 7

One version ties merit awards to both individual and organizational performance. In Table 11.1, an outstanding performer would receive 70% of his or her maximum lump-sum award even if the organization’s performance were marginal. However, employees with marginal or unacceptable performance would get no lump-sum awards even when the firm’s performance was outstanding.

Table 11.1 Merit Award Determination Matrix (an Example)

The Employee’s Performance Rating |

The Company’s Performance |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Outstanding |

Excellent |

Good |

Marginal |

Unacceptable |

|

Outstanding |

1.00 |

0.90 |

0.80 |

0.70 |

0.00 |

Excellent |

0.90 |

0.80 |

0.70 |

0.60 |

0.00 |

Good |

0.80 |

0.70 |

0.60 |

0.50 |

0.00 |

Marginal |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

Unacceptable |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

Note: To determine the dollar value of each employee’s award: (1) multiply the employee’s annual, straight-time wage or salary as of June 30 times his or her maximum incentive award (as determined by management or the board—such as, “10% of each employee’s pay”) and (2) multiply the resultant product by the appropriate percentage figure from this table. For example, if an employee had an annual salary of $40,000 on June 30 and a maximum incentive award of 7%, and if her performance and the organization’s performance were both “excellent,” the employee’s award would be |

|||||

Incentives for Professional Employees

Professional employees are those whose work involves the application of learned knowledge to the solution of the employer’s problems, such as lawyers and engineers.

Making incentive pay decisions for professional employees is challenging. For one thing, firms usually pay professionals well anyway. For another, they’re already driven to produce high-caliber work.

However, it is unrealistic to assume that people like Google engineers work only for professional gratification. So, for example, Google pays higher incentives to engineers working on important projects. 8 And of course, such professionals also receive potentially millionaire-making stock option grants.

Dual-career ladders are another way to manage professionals’ pay. At many employers, a bigger salary requires rerouting from engineering to management, but not all professionals want this. Therefore, many employers have one path for managers and another for technical experts, allowing the latter to earn higher pay without switching to management. 9

Nonfinancial and Recognition-Based Awards

As mentioned in Chapter 10, employers often supplement financial incentives with various nonfinancial and recognition-based awards. The term recognition program usually refers to formal programs, such as employee-of-the-month programs. Social recognition program generally refers to informal manager–employee exchanges such as praise, approval, or expressions of appreciation for a job well done. Performance feedback means providing quantitative or qualitative information on task performance so as to change or maintain performance; showing workers a graph of how their performance is trending is an example. 10

Making incentive pay decisions for professional employees is challenging. For one thing, firms usually pay professionals well anyway. For another, they’re already driven to produce high-caliber work.

Source: Hero Images/Getty Images.

Trends Shaping HR: Digital and Social Media 11

Recognition Apps

Employers are bulking up their recognition programs with digital support. For example, Intuit shifted its employee recognition, years of service, patent awards, and wellness awards programs to Globoforce, an online awards vendor. This “allowed us to build efficiencies and improved effectiveness” into the programs, says Intuit’s vice president of performance, rewards, and workplace. 12 Apps also enable employees to praise each other. 13 For example, one lets employees “give recognition by picking out a badge and typing in a quick note to thank the people who matter most . . . .” 14 Others let users post the positive feedback they receive to their LinkedIn profiles.

One survey of 235 managers found that the most-used rewards to motivate employees (top–down, from most used to least) were: 15

Employee recognition

Gift certificates

Special events

Cash rewards

Merchandise incentives

E-mail/print communications

Training programs

Work/life benefits

Variable pay

Group travel

Individual travel

Sweepstakes

The HR Tools feature elaborates.

HR Tools for Line Managers and Small Businesses: Goals and Recognition

The individual line manager should not rely just on the employer’s financial incentive plans for motivating subordinates; there are simply too many opportunities to motivate employees every day to let those opportunities pass. What to do?

First, the best option for motivating an employee is also the simplest—make sure the employee has a doable goal and that he or she agrees with it. It makes little sense to try to motivate employees with financial incentives if they don’t know their goals or don’t agree with them.

Second, recognizing an employee’s contribution is a powerful motivation tool. Studies show that recognition has a positive impact on performance, either alone or in combination with financial rewards. For example, in one study, combining financial rewards with recognition produced a 30% performance improvement in service firms, almost twice the effect of using each reward alone.

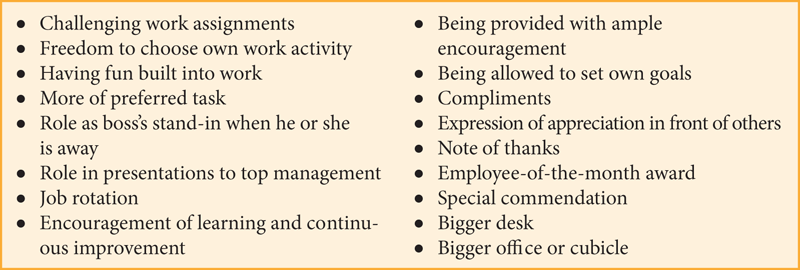

Third, use social recognition (such as compliments) as positive reinforcement on a day-to-day basis. Figure 11.1 presents a list. 16

Figure 11.1 Social Recogniti on and Related Positive Reinforcement Managers Can Use

Source: Bob Nelson, 1001 Ways to Reward Employees, New York: Workman Pub., 1994, p. 19; Sunny C. L. Fong and Margaret A. Shaffer, “The Dimensionality and Determinants of Pay Satisfaction: A Cross-Cultural Investigation of a Group Incentive Plan,” International Journal of Human Resource Management, 14, no. 4, June 2003, p. 559.

Talk About It – 1

If your professor has chosen to assign this, go to www.pearson.com/mylab/management to discuss the following question. You have decided to verify that recognition does in fact improve performance. To that end, you will use an honest observation to praise someone’s performance today. What was the effect of your experiment?

Job Design

Job design (which we discussed more fully in Chapter 4) can affect employee motivation and retention. A study concluded that job design is a primary driver of employee engagement. A study by Towers Watson concluded that challenging work ranked as the seventh most important driver for attracting employees. 17 Job design is thus a useful part of an employer’s total rewards program.

The HR in Practice feature illustrates how employers combine incentives to boost profits.

HR in Practice Using Financial and Nonfinancial Incentives in a Fast-Food Chain

Researchers studied the impact of financial and nonfinancial incentives on performance in 21 stores of a Midwest fast-food franchise. 18 Each store had about 25 workers and two managers. The researchers trained the managers to identify measurable employee behaviors that were currently deficient but that could influence store performance. Example behaviors included “keeping both hands moving at the drive-through window” and “repeating the customer’s order back to him or her.” 19 Then the researchers instituted financial and nonfinancial incentive plans to incentivize these behaviors. They measured store performance in terms of gross profitability (revenue minus expenses), drive-through time, and employee turnover.

Financial Incentives

Some employees in some of the stores received financial incentives for exhibiting the desired behaviors. The financial incentives consisted of lump-sum bonuses in the workers’ paychecks. For example, if the manager observed a work team exhibiting up to 50 behaviors (such as “working during idle time”) during the observation period, he or she added $25 to the paychecks of all store employees that period; 50 to 100 behaviors added $50 per paycheck, and more than 100 behaviors added $75 per paycheck. Payouts eventually rose over time as the employees learned to enact the behaviors they were to exhibit.

Nonfinancial Incentives

The researchers trained the managers in some stores to use nonfinancial incentives such as feedback and recognition. For example, for performance feedback, managers maintained charts showing the drive-through times at the end of each day. They placed the charts by the time clocks. Thus, these store employees could keep track of their store’s performance on measures like drive-through times. The researchers also trained managers to administer recognition to employees. For instance, “I noticed that today the drive-through times were really good.” 20

Results

The programs were both successful. Both the financial and nonfinancial incentives improved employee and store performance. 21 For example, store profits rose 30% for those units where managers used financial rewards. Store profits rose 36% for those units where managers used nonfinancial rewards. During the same nine-month period, drive-through times decreased 19% for the financial incentives group, and 25% for the nonfinancial incentives groups. Turnover improved 13% for the financial incentives group and 10% for the nonfinancial incentives group.

Implications for managers include:

The employee or employees must have specific challenging goals. 22

The link between the effort and getting the incentive should be clear.

Make sure that motivation (rather than, say, poor employee selection) is impeding the behaviors you want to incentivize.

Employees must have the skills and training to do the job.

Employers should support the incentive plan with performance feedback, so employees continuously see how they are doing.

The manager should gather evidence on the effects of the incentive plan over time; make sure it’s indeed influencing performance as you intended. 23

Combine financial with nonfinancial incentives such as recognition.

Talk About It – 2

If your professor has chosen to assign this, go to www.pearson.com/mylab/management to discuss the following question. Lisa and Paul (from the chapter opener) have asked you to design an incentive plan for Mal. How would you apply what you learned in this feature to do so?

Incentives for Salespeople

Sales compensation plans may focus on salary, commissions, or some combination. 24

Salary Plan

Some firms pay salespeople fixed salaries (perhaps with occasional incentives in the form of bonuses, sales contest prizes, and the like). 25 Straight salaries make sense when the main task involves prospecting (finding new clients) or account servicing (such as participating in trade shows). A Buick–GMC dealership in Lincolnton, North Carolina, offers straight salary as an option to salespeople who sell an average of at least eight vehicles a month (plus a small “retention bonus” per car sold). 26

The straight salary approach also makes it easier to switch territories or to reassign salespeople, and it can foster sales staff loyalty. The main disadvantage is that it may not motivate high performers. 27

Commission Plan

Straight commission plans pay salespeople only for results. Such plans tend to attract high-performing salespeople who see that effort produces rewards. Sales costs are proportionate to sales rather than fixed, and the company’s fixed sales costs are thus lower. It’s a plan that’s easy to understand and compute. Alternatives include quota bonuses (for meeting particular quotas), straight commissions, management by objectives programs (pay is based on specific metrics), and ranking programs (these reward high achievers but pay little or no bonuses to the lowest-performing salespeople). 28

However, problems abound. For example, in poorly designed plans, salespeople may focus on making the sale and neglect duties such as pushing hard-to-sell items. 29 Also, in most firms, a significant portion of the sales in one year reflects a “carryover” (sales that would repeat even without any efforts by the sales force) from the prior year. Why pay the sales force a commission on all the current year’s sales if some of those sales aren’t “new” sales from the current year? 30 The following feature presents practical guidelines.

Building Your Management Skills: How to Build an Effective Sales Incentive Plan

How do managers actually design sales incentive plans? The bottom line is that most companies pay salespeople a combination of salary and commissions, with (on average) an incentive mix of about 70% base salary/30% incentive. This cushions the salesperson’s downside risk (of earning nothing), while limiting the risk that the commissions could get out of hand from the firm’s point of view. 31

But getting the best performance from the sales force involves more than the right commissions/sales mix. To maximize the salesperson’s efforts, keep the following guidelines in mind: 32

Salespeople in high-performing companies receive 38% of their total cash compensation in the form of sales incentive pay (compared with 27% at low-performing companies).

Salespeople in high-performing companies are twice as likely to receive stock, stock options, or other equity pay as their counterparts at low-performing companies (36% versus 18%).

Salespeople in high-performing companies spend 264 more hours per year on high-value sales activities (e.g., prospecting, making sales presentations, and closing) than salespeople at low-performing companies.

Salespeople in high-performing companies spend 40% more time each year with their best potential customers—qualified leads and prospects they know—than salespeople at low-performing companies.

Salespeople in high-performing companies spend nearly 25% less time on administration (such as filling out sales forms), allowing them to allocate more time to core sales activities, such as prospecting leads and closing sales.

Incentives’ Unintended Consequences

Wells Fargo and Co. provided a textbook example of ill-designed incentive plans. Its incentive plan drove retail bank employees to hit high sales goals. For example, it required retail bank employees to sell eight banking products per customer. 33 An annual report mentions “cross sell” 20 times; the company calls its retail bank branches “stores.” 34 Wells employees opened accounts for customers without the customer’s permission. At ethics workshops, Wells employees were told not to create fake bank accounts without clients’ knowledge. But the employees knew they had to meet their sales goals, so they did it anyway. 35 Fines, lawsuits, and the CEO’s exit were the results.

Trends Shaping HR: Digital and Social Media

Tracking Sales Commissions

Many employers use enterprise incentive management (EIM) software to track and control sales commissions. 36 For example, Oracle Sales Cloud EIM enables management to easily create scorecard metrics such as number of prospecting calls and sales contracts, and to monitor these in real time on the system’s dashboards. 37 Users can also gamify the sales incentive process with Oracle Sales Cloud, by creating rewards such as points or badges based on each salesperson’s performance.

Incentives for Managers and Executives

An executive’s reward package elements—base salary, short- and long-term incentives, and perks—should align with each other and with the company’s strategic aims. The employer should first ask, “What is our strategy and what are our strategic goals?” Then decide what long-term behaviors (boosting sales, cutting costs, and so on) the executives must exhibit to achieve the firm’s strategic goals. Then shape each component of the executive compensation package (base salary, short- and long-term incentives, and perks) and group them into a balanced plan that makes sense in terms of motivating the executive to achieve these aims. The rule is this: each pay component should help focus the manager’s attention on the behaviors required to achieve the company’s strategic goals. 38 Using multiple, strategy-based performance criteria is best. These include financial performance, number of strategic goals met, performance assessment by the board, employee productivity measures, and employee morale surveys.

One expert estimates that the typical CEO’s salary accounts for about one-fifth of his or her pay. A bonus based on explicit performance standards accounts for another fifth, and long-term incentive awards such as stock options and long-term performance plans account for the remaining three-fifths. 39

Sarbanes-Oxley

Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 to inject more responsibility into executives’ and board members’ decisions. It makes them personally liable for violating their fiduciary responsibilities to their shareholders. The act also requires CEOs and CFOs of a public company to repay any bonuses, incentives, or equity-based compensation received from the company during the 12-month period following the issuance of a financial statement that the company must restate due to material noncompliance stemming from misconduct. 40

Short-Term Managerial Incentives and the Annual Bonus

Employers are shifting from long-term incentives to put more emphasis on short-term performance and incentives. 41 Most firms have annual bonus plans for motivating managers’ short-term performance. Such short-term incentives can easily produce plus or minus adjustments of 25% or more to total pay. Four factors influence one’s bonus: eligibility, fund size, individual performance, and formula.

Eligibility

Employers traditionally based annual bonus eligibility on job level/title, base salary, and/or officer status. Some simply based eligibility on job level or job title, or salary. 42 Recently, however, more employers are offering executives as well as employees below the executive level single annual incentive plans “in which both executives and other employees participate.” 43

Fund Size

How does one determine how big the annual bonus fund should be? Most employers (33% in a recent survey) traditionally use the Sum of Targets approach. 44 Specifically, they estimate the likely bonus for each eligible (“target”) employee and total these up to arrive at the bonus pool’s size.

However, more employers (32%) are funding the short-term bonus fund based on financial results. For example, if profits were $200,000, the management bonus fund might be 20% of $200,000, or $40,000. Most employers use more than one financial measure, with sales, earnings per share, and cash flow the most popular. 45

Individual Performance and Formula

Deciding the actual individual award involves rating the person’s performance and then applying a predetermined bonus formula. Most often, the employer sets a target bonus (as well as maximum bonus, perhaps double the target bonus) for each eligible position. The actual award the manager gets then reflects his or her performance. Other firms tie short-term bonuses to both organizational and individual performance. Thus, a manager might be eligible for an individual performance bonus of up to $10,000, but receive only $2,000 at the end of the year, based on his or her individual performance. But the person might also receive a second bonus of $3,000, based on the firm’s profits for the year. One drawback here is that marginal performers still get bonuses. One way to avoid this is to make the bonus a product of both individual and corporate performance. For example (see Table 11.2), multiply the target bonus by 1.00, 0.80, or zero, depending on the person’s performance (and assuming excellent company performance). Then managers whose performance is poor receive no bonus.

Table 11.2 Multiplier Approach to Determining Annual Bonus

Individual Performance (Based on Appraisal, ) |

Company Performance (Based on Sales Targets, ) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Excellent |

Good |

Fair |

Poor |

|

Excellent |

1.00 |

0.90 |

0.80 |

0.70 |

Good |

0.80 |

0.70 |

0.60 |

0.50 |

Fair |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Poor |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Note: To determine the dollar amount of a manager’s award, multiply the maximum possible (target) bonus by the appropriate factor in the matrix. |

||||

Executives’ Strategic Long-Term Incentives

The employer wants to avoid managers boosting short-term profits by, for instance, delaying required maintenance. They therefore use long-term incentives to inject a long-term perspective into executives’ decisions. Popular long-term incentives include cash, stock options, stock, stock appreciation rights, and phantom stock. PepsiCo’s CEO was paid $26.4 million for 2015, including a base salary of $1.6 million, stock awards of $6.25 million and a performance-based cash bonus of $13.9 million, a $4.26 million adjustment to her pension, plus perks such as air travel. 46

Stock Options

A stock option is the right to purchase a specific number of shares of company stock at a specific price during a specific period. The executive thus hopes to profit by exercising his or her option in the future but at today’s price. This assumes the stock will go up. 47 When stock markets dropped, many employers, including Intel and Google, modified option plans to increase the likely payout. 48

The main problem with stock options is that they often reward even managers who have lackluster performance. A study of CEOs of Standard & Poor’s 1,500 companies found that 57% received pay increases although company performance didn’t improve. 49 Options may also encourage executives to take perilous risks in pursuit of higher (at least short-term) profits. 50

Other Stock Plans

The trend is toward tying rewards more explicitly to performance. For example, instead of stock options, more firms grant various types of performance shares such as performance-contingent restricted stock; the executive receives his or her shares only if he or she meets the preset performance targets. 51 With restricted stock plans, the firm usually awards rights to the shares without cost to the executive but the employee is restricted from acquiring (and selling) the shares for, say, five years. The employer’s aim is to retain the employee’s services during that time. 52

Stock appreciation rights (SARs) permit the recipient to exercise the stock option (by buying the stock) or to take any appreciation in the stock price in cash, stock, or some combination of these. Under phantom stock plans, executives receive not shares but “units” that are similar to shares of company stock. Then at some future time, they receive value (usually in cash) equal to the appreciation of the “phantom” stock they own. 53 Companies also provide incentives to persuade executives not to leave the firm. Golden parachutes are extraordinary payments companies make to executives in connection with a change in ownership or control of a company. For example, a company’s golden parachute clause might state that, with a change in ownership of the firm, the executive would receive a one-time payment of $2 million. 54