10

Making Decisions

Our final tool to help us get things done focuses on decision-making, not least because so many people are appalling decision-makers. Certainly, I was a terrible decision-maker and still have my battles in this respect, usually because I struggle to remove the emotions from my evaluations. Too often, I'm so concerned about my fragile self-esteem I cannot make cool judgements based on my long-term objectives.

No less disabling, I can almost instantly regret any decision. If the positives from any choice loomed large prior to the decisions; once made, it's purely the negatives that come into view. And this can lead to regret and what I call ‘mental paralleling’ in which I fantasize about the perfect and glorious alternative existence I could be enjoying if only I'd made the other choice.

Decisions made at four levels

Mental paralleling is wasteful and exhausting, although I'm right about one thing: good decision-making is an absolutely vital requirement, and one we must understand on our journey towards strong productivity.

In Wharton on Making Decisions (2001) – a series of articles by professors of that famed business school, presented by Stephen J. Hoch and Howard C. Kunreuther – the claim is that decisions are made at four levels: individual (often emotionally driven); as a manager of others (often more formulaic); in negotiation (based on either co-operative or conflictual interactions); and societal (which may be based on principles or values).

Of course, this suggests our primary decision-making level – the personal – is the most emotional and therefore least logical. One of the articles – by Mary Frances Luce, John W. Payne and James Bettman (called ‘The Emotional Nature of Decision Trade-Offs’) – focuses on this conundrum, claiming that most people seek ‘normative’ (or ‘ideal’) judgements based on what they consider appropriate criteria, although this is usually corrupted by the desire to minimize negative emotions. And this may lead to decision-making based on avoiding difficult emotions, rather than seeking the ideal solution.

They offer the example of ‘downsizing’ a department, with the decisions on who to keep based, not on job skills or future needs, but on the family situations of those affected.

‘As the stakes of a decision increase, the desire to find the best normative solution may coexist with the desire to manage or minimize one's negative emotions’, they write.

Such concerns can lead to procrastination, with difficult decisions parked or kicked along the timeline as a form of avoidance. Yet if we can recognize upfront the influence our emotions play – and treat them as just one (though legitimate) factor in the decision – we can avoid them being so disabling, they claim. In the downsizing example this could include job skills, costs, other needs and – yes – the personal consequences for those involved. So emotions are given a legitimate but not dominant place in the process.

Adding to the difficulties here, however, is the issue of ‘confirmation bias’. This means we give more weight to information that confirms our current views – including to emotions such as desire, dislike or fear – which may lead to decisions based purely on prejudice rather than reasoning.

Getting beyond confirmation bias is difficult, although Wharton suggests we focus on our long-term goals and use those as our benchmarks when trying to overcome the barrier of our own emotions or prejudices. In fact, by developing a strong bias towards our long-term objectives, we're recruiting the potential distortions of ‘confirmation bias’ to our needs.

Risk, benefits and costs

Meanwhile, Wharton's business school rival Harvard takes a more pragmatic approach – as offered in Decision Making, the 2006 Harvard Business Essentials guide.

‘In many respects a business [or individual's progress] is a series of decisions linked by implementation and other activities’, it states, before adding that decisions are an inevitable trade-off between the potential ‘risks, benefits and costs’ of any decision.

So how do we make the trade-off? Like Wharton, they recommend that we extrapolate the decision in this case into all three components. Yet this will only help once we can successfully weight the importance of each – a personal concern that brings in Napoleon Hill's notions of desire and faith, as well as worries regarding fears and prejudices.

Weighting dilemmas aside (see below), Harvard asks us to follow a logical process when making decisions.

We must:

Decision trees

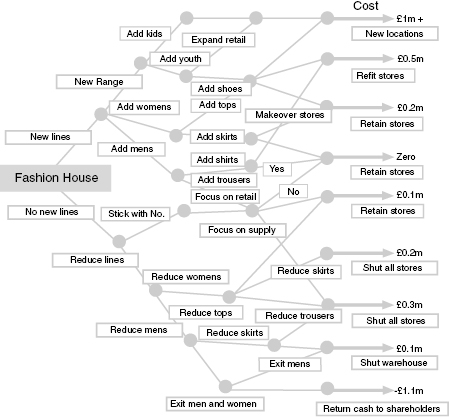

Using a ‘decision tree’ may help. This is similar to a mind map, although (usually) runs left to right. Unsurprisingly, decision trees look like trees, although ones lying on their side – making my preferred metaphor (perhaps due to my childhood fantasies) railway branch lines diverging away from a city-centre terminal. Immediately out of the station will be the key choice or dilemma – a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ dichotomy perhaps (or more likely a comparison between two alternatives) – with further alternatives branching out as we head for the suburbs.

So, if our central dilemma is, say, ‘shall we launch a new product?’ the first two lines out may simply say ‘yes’ and ‘no’ with branch lines from ‘yes’ saying (perhaps if we're a clothes retailer) ‘shirts’ or ‘skirts’, with branch lines from ‘no’ perhaps saying ‘reduce number of lines’ or ‘retain current number of lines’ – and so on. The result should be a diagram that lines up a series of alternative outcomes that, while complex-looking, can be readily understood, even if we've yet to decide the basis for making a decision.

Figure 4 A decision tree showing the options available to a fashion house

In fact, nearly all textbook examples result in a monetary list on the right-hand end of the diagram, or some other empirical (i.e. measurable) outcome. These figures are usually no more than guesses and may not even be the most useful criteria for making a decision, which takes us right back to ‘establishing the context’ of what we're trying to decide.

Avoiding ‘rule of thumb’ thinking

Yet difficulties remain. The confirmation bias mentioned above is what's known as a ‘heuristic’ or ‘rule of thumb’. Nearly everyone employs these when making decisions, often with disastrous consequences, says Harvard professor Max H. Bazerman.

Writing in Judgement in Managerial Decision Making (2005), Bazerman calls this ‘System 1 thinking’, which is intuitive, immediate and emotional, and therefore worth avoiding.

Other common heuristics include:

Certainly, heuristics are deeply ingrained decision-making habits that can lead to a lifetime of flawed decisions, states Bazerman. Yet they're not our only decision-making challenge. Another is the ‘non-rational escalation of commitment’, which may encourage us to continue investing in something that's not working out – say a failing subordinate – in the hope that the new investment will prevent the original investment from being wasted.

This is what's termed ‘throwing good money after bad’: something we may also do with other resources, such as time, effort or even love. Yet the previous investment, says Bazerman, was a ‘sunk cost’ and should therefore no longer figure in our decision-making.

The weighting dilemma

Both Wharton and Harvard focus on organizations, or at least on teams, which means they quickly lose resonance for individuals – perhaps as we stare out of the kitchen window on the horns of a dilemma. Indeed, much of the analysis is aimed at eradicating ‘groupthink’ – the creation of potentially false consent due to the conscious or unconscious avoidance of team conflict. Certainly, one has only to think of the oppressive groupthink that led to Japan's decision to attack Pearl Harbour in 1941 to realize the potential consequences in this respect. Yet it's hardly our most pressing concern as an individual trying to make decisions while alone.

And, for individuals, it's often the ‘weighting’ dilemma that weighs most heavily upon us: how do we turn off our fears or other emotions in order to judge correctly the importance of one element in comparison with another?

The great man Mackenzie may have the answer. In The Time Trap, he spends many pages focused on turning our overarching goals into parcelled-up objectives that require prioritizing for execution. Such a logical process helps get us beyond the brink of a decision because it offers compelling criteria for both evaluation and action. Is this the required next step – a question that should help circumnavigate those potentially emotional concerns?

That said, Mackenzie offers further help by invoking Pareto's 80/20 law as a device for weighting the components of a decision. Vilfredo Pareto was a nineteenth century Italian thinker who demonstrated that, by 1893, 80 percent of Europe's wealth was in the hands of 20 percent of the population – a major improvement in social mobility, in fact, as prior to industrialization wealth was far more intensely concentrated. Yet Pareto's law is now most often associated with the assumption that 20 percent of our tasks or effort yield 80 percent of the results (which is how Mackenzie employs it).

To me, this is a fantastically enlightening concept, not least because it offers us a benchmark for the weighting of decision-making criteria. Given that most decisions are, in reality, a series of choices regarding the application of resources, we can now evaluate them by seeking the 20 percent of resource application likely to yield 80 percent of the desired result.

Of course, we need to factor in risk: the likelihood that we'll achieve such a result (it may require a lot more than 20 percent and achieve well below 80 percent). But even here we now have a strong benchmark: our guess at the probabilities of meeting Pareto's 80/20 rule.

In fact, entrepreneur Richard Koch was so taken by 80/20 thinking that he wrote a series of books imploring us to convert our entire lives into 80/20 judgements. Koch's claim is that this is a universal law: ‘All human history, all progress in civilization, involves getting more with less,’ he writes in Living the 80/20 Way (2005), adding that the law applies to all animals, groups and individuals.

Does the decision you make give you not only a better solution, but an easier one, he asks? Because unless it's both it's unlikely to lead to sustainable improvements.

Of course, life's not so simple. Other responsibilities crowd in on us constantly, although Pareto's law can help us decide between equal alternatives by calculating which one is the slow-and-reluctant donkey, and which one the seemingly effortless Porsche.