2

THINK CHINA AND INDIA, NOT CHINA OR INDIA

When someone brings China and India together, it will be a big story.1

—Shiv Nadar, chairman and CEO, HCL Technologies

Surprising as it may seem, far too many companies still spend considerable time and energy debating whether to focus on China or India. The question is certainly important enough that in their popular series in BusinessWeek, Jack Welch and Suzy Welch devoted an entire column to the topic “choosing China or India.”2

Our central thesis in this chapter is that for most Fortune 1000 companies, the time for this debate is over. The right question to ask is how best to pursue both China and India rather than which one. A company can derive several benefits from an integrated China+India strategy. It can capture the scale benefits from going after two (rather than just one) of the largest and fastest-growing markets in the world. It can leverage the complementary strengths of both countries. It can transfer learnings from one market to the other, thereby accelerating the pace of success in both. And it can use presence in both countries to reduce the level of overall risk associated with operating in just one of them. In short, a smart company can use a China+India strategy to align itself with the rapidly growing economic integration between the two countries.

China and India: Cousins, Not Twins

We begin with an overview of the major similarities and differences between China and India.

Vast Sizes and Populations

At 9.6 million square kilometers, China's surface area is virtually identical to that of the United States. At 3.3 million square kilometers, India is a smaller country. Nonetheless, it is still almost as large as the twenty-seven-country European Union (EU), which has a surface area of just over 4 million square kilometers. In terms of population, China at 1.3 billion and India at 1.1 billion are less far apart. Also, both are much larger than either the United States (299 million people) or the EU (493 million people). In essence, both China and India are continents. These numbers also tell us that despite their large surface areas, China and India have very high population densities: China (135 people per square kilometer) and India (333 people per square kilometer) versus the United States (31 people per square kilometer) and the EU (123 people per square kilometer). Not surprisingly, China and India already account for four of the ten largest megacities in the world.

I = C – 12: Rapid Economic Growth and China's Twelve-Year Lead

As the two fastest-growing economies in the world, China and India are growing rapidly in absolute as well as relative terms. However, China's rapid growth started several years earlier than India's. And even today, China continues to grow somewhat faster than India. In 1980, China and India had roughly the same, albeit very low, per capita incomes. Since then, China's economy has grown to become almost three times as large as that of India. Deng Xiao Ping kick-started the economic revolution in China around 1979. In contrast, India started on the path of domestic liberalization and global integration in 1991, fully twelve years later. That twelve-year gap remains alive and well today. According to our analysis, the simple equation I = C – 12 captures a vast proportion of the economic differences between India and China today.

Most of the key economic indicators for India in 2006–2007 look strikingly similar to the figures for China in 1994–1995. Similarly, projecting ahead, if you take India's GDP for 2007 and compound it at an 8 percent annual growth rate, it turns out that India's GDP in 2020 should be the same as China's GDP in 2007. Might India be ready to host the summer Olympics in 2020 in as impressive a fashion as China did in 2008? We deem such a scenario highly likely.

India's Demographic Dividend

The median age of India's population is 24.3 years as compared with 32.6 years for China. Because of the one-child policy, China's population is not only eight years older than that of India, it is also aging faster. As a result, China's dependency ratio is on the rise, whereas that of India is declining. Given this demographic dividend, most analysts expect that from around 2020 onward, India's economic growth is likely to exceed that of China.3 Looking at the inevitable aging of the population, a common refrain among China's policymakers is, "China must get rich before it gets old."

Manufacturing Sector

In 2006, manufacturing accounted for 47 percent of China's GDP but only 28 percent of India's. Taking into account China's much higher GDP, this implies that China's manufacturing sector ($1.2 trillion in 2006) is five times as large as that of India ($251 billion in 2006). China's lead over India in the manufacturing sector is formidable. It rests on several sources of comparative advantage: larger scale at the plant level, greater experience, significantly better infrastructure, and more compliant labor. China has been a manufacturing and export powerhouse since the early 1990s. The manufacturing revolution in India, now in full swing, started only around 2005.

Services Sector

In 2006, services accounted for 41 percent of China's GDP but 55 percent of India's. In particular, India is far ahead of China in software services as well as most other types of services that can be delivered remotely by information technology. Examples of the latter range from low-end commodity services (such as call centers) to high-end knowledge-intensive services (such as software development, chip design, market research, marketing analytics, legal research, securities analysis, drug discovery services, and so forth). India's lead over China in these types of IT-enabled services rests on several sources of comparative advantage: native fluency in the English language, economies of scale, over twenty years of experience in serving global customers, incorporation of Toyota-like process discipline and rigor into the creation and delivery of services, and deep domain knowledge of key customer industries. Including foreign multinationals such as IBM and Accenture, almost ten IT services companies have an India-based professional staff numbering over fifty thousand each. In contrast, in China, the largest IT services company has a staff of only around ten thousand.

Infrastructure

China's physical infrastructure (such as highways and paved roads, rail lines devoted to goods transport, seaports, and airports) is significantly more developed than India's.4 This is due in part to more effective policymaking and implementation in China and in part to the fact that China started to invest heavily in infrastructure in the mid-1990s, something that India is beginning to do only now. Between 1998 and 2005, China spent 8.2 percent of GDP on hard infrastructure as contrasted with India's 4 percent. Indian policymakers appear to have finally realized the huge constraints that weak infrastructure puts on the development of the country's manufacturing sector and exports. Working on a strategy of public-private partnership, a new five-year plan that commenced in 2007 is intended to double annual investments in infrastructure.

Foreign Direct Investment

Over the past ten years, China has attracted about ten times as much foreign direct investment (FDI) as has India.5 The following are some of the major reasons for this difference: until recently, major tax breaks given by the Chinese government to foreign-invested enterprises,6 the attraction of a larger domestic market within China, much better infrastructure, and more compliant labor. In 2005, China attracted a net inflow of over $75 billion in FDI as compared with only $6.6 billion for India. However, the pace of FDI inflow into India has started to gather steam. Inbound FDI in India was about $16 billion in 2006 and about $25 billion in 2007; the projected figures for 2008 are $40 billion.

Energy Scarcity

As large, rapidly growing economies, China and India share the same challenges with respect to energy shortages. In 2006, China consumed 7.4 million barrels of oil per day and imported about 50 percent of it. India consumed 2.6 million barrels per day, with imports supplying almost 69 percent of this need.7 Over the coming decade, the situation is likely to get worse. Governments, companies, and people in both countries are responding to this situation in roughly similar ways. Both governments are on an active hunt to secure access to energy resources outside their borders, especially in Africa. At the same time, both societies have dramatically increased their reliance on renewable (nonfossil) energy sources such as wind, solar, and nuclear. In 2007, China and India were already among the world's top four countries in terms of installed wind power capacity. Excluding electricity and heat trade, China and India already derive 15 and 40 percent, respectively, of their energy from renewables, as compared with less than 5 percent for the United States. Also, China and India generate only 2.3 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, of their electricity from nuclear power. Compare these figures with those for the United States (19.4 percent), Japan (30 percent), Germany (31.8 percent), and France (78.1 percent). It is clear that China and India will have to dramatically increase their reliance on nuclear power over the next two decades.

Environmental Degradation

China and India also share similar environmental challenges, for example, emissions of carbon dioxide. In 2005, China and India were among the five largest emitters of energy-related carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, the other three being the United States, Russia, and Japan. Yet on a per capita basis, China's emissions at 3.92 tons per capita and India's at 1.09 tons per capita were a small fraction of the figures for the United States (19.4 tons per capita) and Japan (9.4 tons per capita).8 Herein lies the challenge for both China and India as well as the developed countries. Since carbon dioxide emissions affect all of humanity and global warming has reached alarming proportions, it is unimaginable that China and India can continue to focus solely on per capita figures. At the same time, it also is unthinkable that they will forgo future economic growth for the sake of the environment. Such a situation offers both enormous challenges as well as opportunities: challenges for the governments in terms of how to come to an agreement regarding cuts in emissions that would be fair to all parties, rich as well as poor, and opportunities for corporations that see the writing on the wall and go full blast to make their products and services radically more efficient on both fronts: energy use and environmental impact.

Health and Primary Education

China ranks ahead of India in health and primary education. The 2006–2007 Global Competitiveness Report by the World Economic Forum ranks China at number 55 and India at number 93 (out of a total of 125 countries) on measures of health and primary education. According to the World Bank's data for 2005, life expectancy at birth in China was 71.8 years versus that for India at 63.5 years. The estimated adult literacy rate in China is 91 percent, whereas that in India is 61 percent.

Innovation Drivers

The 2006–2007 Global Competitiveness Report ranks India ahead of China in higher education and training (number 49 versus number 77). Historically, India has placed much greater emphasis on tertiary education, whereas China's emphasis has been much stronger on primary and secondary education. However, recent policy changes in both countries are leading toward a convergence over the next twenty years. The Global Competitiveness Report also ranks India ahead of China in technological readiness (number 55 versus number 75), business sophistication (number 25 versus number 65), innovation (number 26 versus number 46), and company operations and strategy (number 25 versus number 69). Unlike China's economic isolation between 1949 and 1979, India's economy always remained integrated with the global economy. Thus, Indian managers have had much longer exposure to Western management thought. Also, India started establishing elite business schools in the 1960s, a process that China did not embark on until the late 1990s.

Political Institutions

It is no secret that China and India differ greatly in the structure of their political institutions. China's is a command-and-control economy. Senior political leaders are appointed by the Communist Party of China, and the media are expected to help implement national policies. In contrast, India is a free-wheeling democracy modeled after that of the United Kingdom. Political leaders are elected by the citizens, and the media remain free from government censorship. It is important to note, however, that China's political system is far from monolithic. It is already the reality today, and will become increasingly so in the coming years, that different ministries and bureaus within China may have serious policy disagreements with each other. Similarly, policy disagreements (if not officially, then in terms of de facto implementation) are becoming increasingly common between the central government and those at the provincial and local levels.

Social Culture

But for differences in language and food, most Indians would feel quite at home within a Chinese family and vice versa. In both cultures, caring for the family (in particular, children) is paramount. Both societies place equally high value on education and saving for the future. They are also like-minded on the importance of face, that is, respecting the dignity of others—in particular peers, superiors, and elders. Thus, in both cultures, people feel equally uncomfortable in saying “no” outright. Notwithstanding these enormous similarities, the Chinese and Indian cultures do differ in at least one important respect. Given the centrality of religious beliefs in India, its culture is far more spiritual than that of China. Given the lack (or weakness) of religious beliefs in China, its culture is far more pragmatic than that of India.

Summing up, we see the Chinese and Indian societies and economies as akin to cousins rather than either twins or total strangers. Although there are important differences, the similarities between the two are also large.

Growing Economic Integration Between China and India

But for a brief border war in 1962 and the subsequent tensions that keep rearing periodically, China and India have enjoyed a mutually harmonious relationship going back at least two thousand years. The ties that brought China and India together were religious and intellectual, as well as economic. As illustrative examples, consider the following. Buddhism was founded in India around the fifth century B.C.E. and then made its way into China. In the eighth century, an Indian scientist was appointed by China as the president of its Board of Astronomy. And the famous fifteenth-century Chinese admiral Zheng He (who reportedly had a more impressive fleet than that of Christopher Columbus) visited India often and played an important role in expanding trade links between the two countries.

In modern times, the period from 1949 to 2000 could be seen as the dark ages, an era of almost complete economic isolation between the two countries. Bilateral trade and investment came to a halt and was essentially insignificant. The current decade, however, has seen a near-complete transformation of the economic relationship between China and India. The primary driver of this transformation has been the fact that starting in the 1990s, both countries have become increasingly outward looking in their economic policies and thus embraced a deepening of their economy's integration with the rest of the world. Importantly too, both China and India are now fellow members of the World Trade Organization.

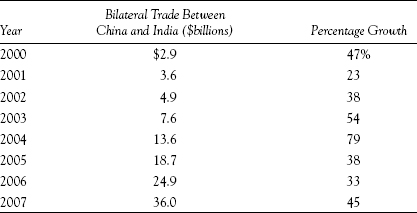

Table 2.1 tracks the growth of China-India bilateral trade since 2000. It is clear that the economies of China and India are becoming rapidly intertwined. In the current decade, trade between the two countries has grown twice as fast (about 50 percent annually) as each country's trade with the rest of the world (about 23 to 24 percent annually).

Table 2.1 Growth of China-India Trade

Source: Abstracted from data obtained by the authors from the Ministry of Commerce, People's Republic of China.

Few people outside China and India are aware that by the end of 2007, China had become India's number one trading partner. From China's side, India is now one of its top ten trading partners. Also, China's trade with India is growing far more rapidly than its trade with the other nine. Thus, India is rapidly becoming an increasingly important trading partner for China too.

Our computations indicate that after adjusting for partner GDP (bilateral trade divided by the trading partner's GDP), India's trade with China is greater than that with Japan, the United States, or the entire world. After similar adjustments, China's trade with India is only slightly below that with Japan, the United States, or the entire world.

Even if the growth rate in India-China trade slows to 25 percent annually from the current rate of about 50 percent, bilateral trade between them will be almost $75 billion in 2010 and $225 billion in 2015—as large as China-U.S. trade just three years ago. These are very large numbers. Political and business leaders need to start getting ready now for this radically different world.

Trade is only one of the two major economic ties that bind nations. The other is investment. We predict that the investment links between India and China are likely to grow even faster than trade links. This would be an important development because investment links imply much deeper integration than trade links. At present, investment links between the two countries are relatively modest. Haier in home appliances, Huawei in telecommunications equipment, and Lenovo in PCs have a significant presence in India. Similarly, some Indian companies such as Bharat Forge in auto components, Suzlon in wind turbines, and Tata Consulting and Infosys in IT services are building a presence in China. These types of greenfield investments will continue to grow. However, the quantum leap will happen as some of the bigger companies from India and China acquire third-country companies that already have a large presence in the other country.

Consider, for example, Tata Motors's recent acquisition of Jaguar and Land Rover from Ford Motor Company. Given Jaguar and Land Rover's positions in the Chinese market, Tata Motors now finds itself with almost $2 billion in revenues from China. This is a large number and will have a significant impact on the centrality that Tata Motors accords to the Chinese market. Also, given Tata Group's trend-setter status in India, its strategic moves and mindset shifts are likely to have spillover effects on the rest of Indian industry.

Obviously it is hard to predict who will buy whom over the coming years. However, it is certain that over the next five to ten years, the world will see a growing number of foreign acquisitions by Indian and Chinese companies. As these acquisitions materialize, it is inevitable that investment linkages between India and China will grow rapidly.

To sum up, the rapid and multifaceted growth in economic integration between India and China will have profound implications for political and business leaders. The world is watching the rise of China and India with fascination. However, most people do not realize that the implications of tighter economic links between the two could be even more profound.

We now discuss the details of how a combined China+India strategy can benefit multinational enterprises with a presence in both countries.

Strategic Implication 1: Leverage the Scale of Both China and India

The first major benefit from a combined China+India strategy is that the company can capture the compelling growth opportunities, as well as the associated scale efficiencies, offered by a committed pursuit of the markets in both countries.

Consider the case of the PC industry. Worldwide PC shipments grew about 12 percent from 239 million units in 2006 to 268 million units in 2007. At a growth rate of about 5 percent, the U.S. market is largely mature. The biggest growth opportunities lie in China and India, where PC shipments are growing at over 20 percent annually. It appears quite likely that China will emerge as the world's largest PC market by around 2013 and India the second largest by around 2020. Stephen J. Felice, Dell's senior vice president for Asia-Pacific, has observed: "India is Dell's largest-growing country in the world … [with] 50% to 70% year-on-year growth in the foreseeable future."9 As the major PC vendors (HP, Dell, Acer, and Lenovo) look at these trends, it is clear that none of them can hope to remain (or emerge) the global leader without a committed pursuit of PC buyers in both China and India.

The importance of leadership in the Indian market appears particularly crucial for Lenovo, the dominant player in China (35 percent market share in 2007) but relatively weak globally (7.5 percent market share in 2007). Among the major markets outside China, India is not only the fastest growing but, as a relatively young market, also the most fluid in terms of Lenovo's (or any of the other big players') ability to shift market shares. In the United States and Europe, which are more established and relatively more mature, it is a much tougher challenge for Lenovo to steal market share from the larger incumbents. Not surprisingly, Lenovo sees India as a major plank in its strategy for global dominance. In one of its key moves, on January 1, 2006, the company restructured its global operations from four regions to five. Prior to the restructuring, the four regions were the Americas; Europe, Middle East, and Africa; Asia-Pacific excluding China; and China. After the restructuring, India was carved out of Asia-Pacific to be managed as a region in its own right.10

A combined China+India market strategy becomes even more important when major elements of the cost structure are subject to significant economies of scale and the profit margins are likely to be razor thin. This is increasingly the case for ultra-low-cost products targeted at the middle- and low-income segments of emerging markets. Take the case of the EC280, a new desktop Dell introduced in March 2007 for first-time buyers in emerging markets.11 EC280 is a compact machine that occupies one-eighth the space of a regular desktop. It uses a low-end Intel microprocessor and comes loaded with Microsoft Windows. In 2007, the starting retail price for the complete machine including monitor was about $335. If you consider the fact that novice buyers would be buying this desktop from a retail store rather than online (thus necessitating a margin for the retailer), it is clear that the profit margins for Dell on this machine must be very slim. Such a product strategy can be economically viable only if Dell can leverage sales of this machine not only across the vast market in China but also that in India, as well as other major emerging markets such as Brazil.

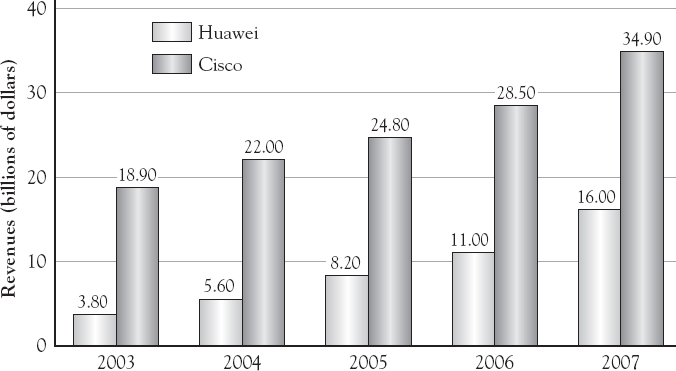

The global battle between Cisco Systems and Huawei Technologies also provides an interesting example of the criticality of pursuing a combined China+India market strategy. Headquartered in China, Huawei is one of Cisco's toughest challengers on the global stage (see Figure 2.1 for a comparison of the revenue figures for Cisco and Huawei over the last five years).

Figure 2.1 Revenues for Cisco and Huawei, 2003–2007 (billions of dollars)

Huawei's competitive advantage rests heavily on cost leadership and derives primarily from the fact that the bulk of its R&D and manufacturing operations are based in China. Huawei's cost competitiveness has made it particularly attractive to customers in emerging markets. In fact, in 2007, Huawei derived 72 percent of its revenues from markets outside China, largely in emerging economies. According to media reports, as well as our own interviews with telecom operators in India, Huawei has publicly stated that one of its strategic goals is to become India's number one supplier of telecom infrastructure equipment.12 The implications for Cisco are clear: it must regard Huawei as a serious competitor and build a counter-strategy that rests on at least three legs: ongoing sustenance of technological advantage over Huawei, a drastic reduction in cost structure to reduce or eliminate Huawei's cost advantage, and an attack on Huawei in both of its key strategic markets: China and India.

Strategic Implication 2: Leverage the Complementary Strengths of China and India

While Chinese and Indian economies will exhibit a remarkable degree of convergence over the next twenty years, in the near term, they offer complementary strengths that a smart global company can profitably exploit. China is much stronger than India in physical infrastructure and manufacturing efficiency. India is much stronger than China in software development, IT-enabled services, and many types of analytical and knowledge-intensive tasks such as legal research, finance and accounting, and advertising.

China's advantage over India in most areas of manufacturing is well known. As we noted earlier, China's manufacturing sector is currently five times as large as that of India. Thus, in many industries, Chinese manufacturers have a significant scale advantage over their Indian counterparts. In the manufacturing sector, they also enjoy other advantages, such as a significantly better logistics infrastructure (roads, railways, and ports), significantly greater experience at responding effectively and efficiently to the needs of foreign customers, and a more compliant labor force. It should be noted that as of late 2007 and early 2008, labor costs, especially in southern China, were on a steep climb due to a combination of tougher labor laws and an appreciating currency. Notwithstanding these developments, in most industries, China's manufacturing sector remains (and, for several years, is likely to remain) well ahead of India's.

In reverse, India's lead over China in IT services is equally well known. India's IT services sector is more than five times as large as that of China. Also, paralleling China's comparative advantage in manufacturing, India's lead in IT services rests on multiple factors: a very strong export orientation, extensive experience at remote delivery of IT services to global clients, highly developed process rigor, in-depth knowledge of specific industries, and fluency in the English language.

IBM Corporation provides a near-perfect example of how to leverage the complementary manufacturing versus IT services capabilities of China and India. IBM has built its largest procurement center outside the United States in Shenzhen, China. Sourcing from Asian (primarily China-based) suppliers accounts for about 30 percent of the company's $40 billion annual procurement budget. On October 1, 2006, IBM even relocated its chief procurement officer, John Paterson, to China. As Paterson noted in his letter to the company's suppliers, "This [move] places us closer to the core of the technology supply chain which is important, not only for IBM's own internal needs, but increasingly for the needs of external clients whose supply chains we are managing via our Procurement services offering. As IBM's business offerings continue to grow, we must develop a deeper supply chain in the region to provide services and human resource skills to clients both within Asia and around the world."13

In contrast to IBM's heavy reliance on China for hardware procurement, the company has made India the global center for the delivery of IT services. At the end of 2007, IBM employed over seventy thousand IT professionals in India—about 20 percent of its global workforce and four times its staff size in China. The vast majority of the India-based staff was being deployed to serve the needs of IBM's global clients. In short, IBM Corporation had made China one of its most important global hubs for hardware procurement and India one of its most important global hubs for the delivery of IT services.

The complementary strengths of China and India extend beyond manufacturing and IT services. China's chemical industry (particularly specialty chemicals) is significantly more advanced than India's. Also, certain types of pharmaceutical raw materials are available more abundantly and at lower cost in China than in India. Thus, many Indian pharmaceutical companies rely on China as one of their primary suppliers of pharmaceutical ingredients.

In turn, India is emerging as an important source of specialized talent (finance, accounting, and global marketing) for many Chinese companies as well as the Chinese units of major multinationals. To quote Andrew Tsui, chairman of southern China for Korn/Ferry International, an executive search firm, "Through the MNC executive circuit, Indian executives have good exposure to modern management principles, are exposed to the challenges of emerging markets and can communicate well in English."14 Shenzhen-headquartered Huawei Technologies is one example of a Chinese company that has begun to use Indian executives to crack open English-speaking markets.

Another nontraditional area where India is emerging as a complement to China is the country's highly developed skills in creating ads for diverse markets. Paralleling similar moves by other global agencies, in mid-2007, Interpublic Group PLC announced the launch of a twenty-four-hour production studio in India whose creative staff would work alongside colleagues in New York and London to create ads for global accounts. The roots of India's comparative advantage in advertising lie in the country's individualism (which fosters creativity) and the world's highest degree of linguistic and religious diversity (which fosters skills at creating ads that can work across diverse languages, religions, and cultures with minimal adaptation). In a telling example of a Chinese company that is keenly aware of the complementary strengths of China and India, Lenovo centralized its global advertising activities to a hub in Bangalore in mid-2007. The new hub is responsible for the creation of Lenovo's ads for the entire global market (with the notable exception of China). While Lenovo will leverage India's strengths for global advertising, it will continue to leverage China's strengths for low-cost manufacturing.

Strategic Implication 3: Transfer Learning from One Market to the Other

The combination of enormous similarities yet important differences between China and India offers considerable opportunities for multinational corporations with operations in both countries to transfer learning from one to the other. Were the two markets to be radically different, there would be severe limits on the relevance or the transferability of ideas across them. And were the two to be virtually identical, there would be little to learn from each other. Thus, the similarity-difference ratio between China and India provides major opportunities for multinational corporations to benefit from the mutual transfer of lessons from their operations in the two countries. Such knowledge transfer can benefit companies by reducing the likelihood of costly errors and accelerating the ramp-up to successful operations.

Business and political leaders in both countries are well aware of the potential for mutual learning. Consider, for example, the following excerpt from an article titled, "Dalian: China's Bangalore," in China International Business:

In terms of software exports, Dalian places third among Chinese cities, behind Shanghai and Beijing. But significantly, it is the city currently placing the most emphasis on software, with the aim of making it Dalian's central industry. The local government, citing the example of Bangalore, known as the Silicon Valley of India, is doing its best to promote the development of the industry…. "Developing the software industry is the best choice for us,' says Xia Deren, who has been mayor of Dalian since 2003.15

Look now at the following observation by Anand G. Mahindra, CEO of India's $6 billion revenue Mahindra Group:

China is the best thing that happened to India. Now we can say to the politicians, “Look, this is our competition, this is what they're doing. Why aren't we?” It's something to whip up our competitiveness. China is the benchmark…. For a country that invented yoga, the science of stretching, we just didn't stretch ourselves.16

A combined China+India strategy can provide a company opportunities for knowledge sharing in virtually all elements of the value chain. We identify two of the most important areas.

First, we look at market development and go-to-market strategies. The fact that China's economy is twelve to fifteen years ahead of India's provides many companies with a significant opportunity to leverage the lessons from China to fine-tune their strategies for the Indian market at a faster pace. China's PC industry, for example, is almost four times as large as India's. Aside from size, however, the Chinese and Indian markets share many common features: extremely rapid growth, large proportions of first-time buyers, the need to reach customers not just in tier 1 markets but also tiers 2 to 4 and even smaller markets, the importance of selling through the retail channel, very low buying power, low penetration of credit cards, and a need for local language software.

Although the two markets are not identical, many important features of business models can be shared across both markets, and Lenovo is attempting to do so in a systematic way. William J. Amelio, Lenovo's president and chief executive, had this to say:

One of the first things we [did] was to say, let's figure what the essence is of the China model and then can we employ it somewhere else? India was a great first choice. Essentially we had a 167-page manifesto. We had the team figure out how to distil that down to five salient points that we could then implement in any country. And then we put together a Swat team that understood the essence of that and was able to go into the country and implement. We've been highly successful in India.17

The PC industry is just one of hundreds of business areas where companies can transfer lessons from China to India (and vice versa) in order to reduce the time needed to hone their strategies for both markets.

The second important area is frugal designs for products, services, and solutions. China and India are unique among the major economies in that they are both rich and poor at the same time. Both have market sizes that are almost as large as, and growing faster than, the rich countries of western Europe. Both also have rapidly growing numbers of very affluent people. Importantly, however, the vast majority of the population in both countries is extremely poor by Western standards. Per capita income in China is one-twentieth and in India one-fortieth of that in the United States.

Thus, unless a company sells high-end niche products such as Louis Vuitton bags or Porsche cars, it has little choice but to invent products, services, and solutions that can be sold at ultralow prices while still yielding satisfactory profit margins. There is no need for a company to engage in such frugal innovation separately for China and India. A frugal design that works in one market should generally need only minor adaptations for the other. FonePlus, a prototype product developed by Microsoft China in mid-2007, is a cell phone with a built-in Windows operating system that, when connected to a TV and keyboard, can morph into a low-end computer. Microsoft views FonePlus as a multicountry product that could have as big a market in India as in China.18

The notion of frugal designs that will work across both China and India can be generalized to include products and services that are frugal in terms of raw material use and impact on the external environment. Given their rapid growth rates and vast populations, China and India have already emerged as two of the biggest contributors to the scarcity of virtually all commodities (including crude oil) as well as degradation of the environment. Admittedly, on a per capita basis, oil consumption in China and India is a small fraction of that in the developed countries. However, given the large populations, the absolute numbers become very large. The same is true for carbon dioxide emissions from China and India: they are small in per capita terms but huge in absolute terms.

It seems unlikely that either China or India will abandon rapid economic growth for the sake of the broader humanity. At the same time, it also is impossible to imagine how they can continue to suck in ever larger quantities of raw materials and spew out ever larger quantities of harmful emissions. The solution to this dilemma must (and will) lie in new products and services that are designed to be ultraefficient in terms of raw material use and impact on the external environment and yet extremely cheap in terms of total cost. An example is the MAC 400, an electrocardiogram unit being developed by GE at the John F. Welch Technology Centre in Bangalore. This machine is smaller than an average laptop, works on battery power, and can be handled by a medical representative rather than a doctor.19 The market for this machine should be as large in China as in India, not to speak of other emerging markets such as Brazil and Indonesia.

Strategic Implication 4: Leverage Dual Presence to Reduce Risks

The fourth major benefit that a combined China+India strategy can yield pertains to the potential for risk reduction offered by dual presence. The opportunities for risk reduction exist in at least three areas.

First, dual presence can reduce exposure to political risk. Given rapid changes in their economies, governments in both China and India are still trying to figure out whether and how to differentiate between domestic and foreign enterprises and what types of policies to adopt for each category of firms. Also, as illustrated by China's new enterprise income tax law (which became effective on January 1, 2008, and eliminates the tax advantages that foreign enterprises had historically enjoyed over domestic ones) and a new antimonopoly law (which became effective on August 1, 2008, and may put new restrictions on acquisitions within China by foreign firms), future changes in public policy need not necessarily favor foreign enterprises. In the case of India, policy uncertainties also derive from the fact that the government is often ruled by a coalition of widely disparate partners and that the incumbents almost always lose in the next election. A multinational enterprise with a dual presence in both China and India is likely to be exposed to a lower level of total risk as compared to one with presence in just China or just India.

Second, dual presence can reduce exposure to economic risks such as currency fluctuations and shifting labor costs. Over the twelve months from early 2007 to early 2008, manufacturing costs in southern China (especially in labor-intensive industries such as shoes) increased by as much as 40 percent due to a variety of factors: a rapid increase in the cost of raw materials and energy; a new labor law that protects workers' rights more stringently than before; growing economic opportunities in central and western China, which have made migrant workers less willing to move to the coast; elimination of preferential tax policies for foreign companies; and a growing national emphasis on cleaner industries. Thus, increasing numbers of companies with manufacturing presence on China's east coast have begun to explore relocating to inland China or India and Vietnam. A recent study by the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai noted that over half of foreign manufacturers in China believe that the mainland is beginning to lose its manufacturing advantage over India and Vietnam.20

Finally, dual presence in China and India can reduce a company's exposure to intellectual property risk. A way to realize this benefit is by disaggregating and distributing core R&D and core component production across China and India as well as other countries. Consider the case of a European manufacturer that sells machinery to construction contractors. Burned by the experience of seeing its former Chinese partner produce copycat versions of an earlier model, this company has consolidated the production of some subsystems in India and others in China, while keeping assembly operations localized within each country. Such an approach permits the company to benefit from the low manufacturing costs in each country. At the same time, it reduces the extent to which the totality of the company's design blueprints and manufacturing processes are exposed to local partners or job-hopping local employees.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding a certain degree of economic rivalry and unresolved political tensions between China and India (as between China and Japan, and China and the United States), we deem it inevitable that economic ties between the two countries will continue to grow and become increasingly significant in absolute terms. By 2025, it is highly probable that China-India economic ties (through trade, investments, and technology linkages) may be among the five to ten most important bilateral relationships in the world. The rising dragons and tigers from China and India will be one set of beneficiaries from this trend. However, to the extent that multinational enterprises from outside China and India (such as Cisco, GE, IBM, or Nokia) are likely to be less directly affected by the occasional political tensions between the two countries, the potential benefits from a combined China+India strategy are likely to be even greater for these third-country multinationals.