3

The first 5 bricks

I was 11 years old when I tried to make my first pavlova (a meringue‐based dessert that's iconic in New Zealand and Australia). It's considered an easy dessert to make: you just need five ingredients, and the recipe I used suggested only 1 out of 5 stars for difficulty.

Surely, I could do this.

Part of the recipe included separating the egg whites from the egg yolks. I must admit I've never been the most meticulous person — I'm okay with letting a few things slide — so I separated the egg whites without putting much attention into it, not really caring that there were traces of yolk in the whites. After all, what's a few drops of the wrong ingredient going to do?

I was so excited to finally pull my crispy white pavlova out of the oven, and instead was dismayed to see a gooey yellow mixture that had bubbled out of the cake tin and onto the floor of the oven. I was both hungry and heartbroken. I didn't initially understand how it could all have gone so wrong. After all, it was just egg yolk! How could it affect the baking like this?

I was so scared by my mistake I never made pavlova again. That moment taught me a valuable lesson. Even for the simplest tasks, carelessness and a lack of preparation can turn your work into custard.

Or in my case, something that resembled custard.

The world of investing is no different, but let's switch metaphors here. It's important to have our foundations of personal finance established before we begin our journey to wealth. Then, brick by brick, we build on what ends up becoming the foundation of generational wealth that we and our future generations can reap the rewards from and build on further.

I'll be the first to admit that, in a world where everything can feel instantaneous, growing wealth slowly can sound painful. It's like wanting to start a sprint now but knowing you need to first hit the gym and build up your cardio. The excited part of you wants the results now, but the wise part of you knows you need to get the foundations sorted first.

Laying your financial foundations: the first 5 bricks

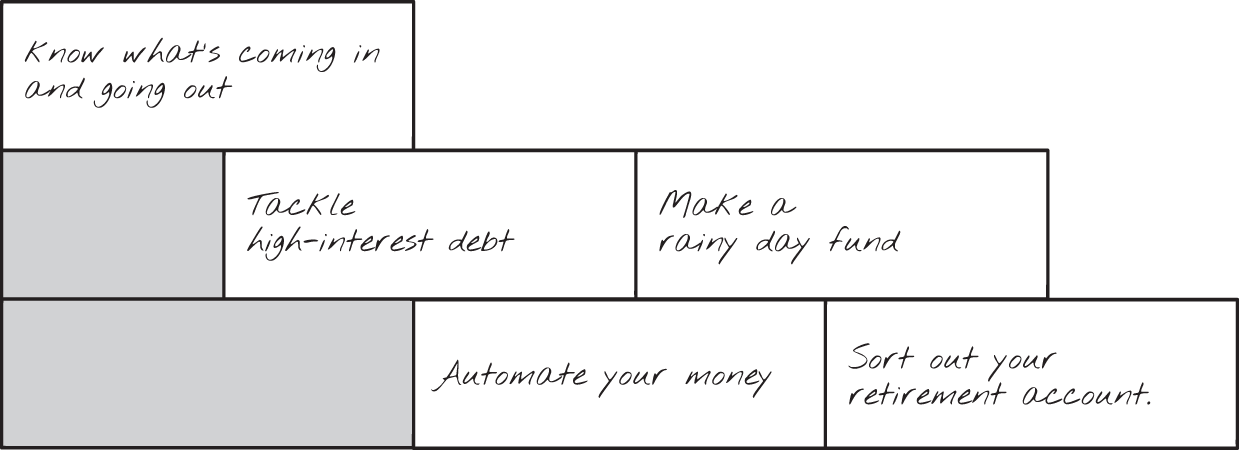

Before we begin investing, there are five personal finance concepts to tackle (the bricks in your foundation — see figure 3.1) so that you begin on the right foot. It's an important part of your overall financial wellness and you'll be thankful that you had this part sorted out before you bought your very first stock or fund. So, to lay your financial foundations, you should:

- know what's coming in and going out

- tackle high‐interest debt

- automate your money

- make a rainy day fund

- sort out your retirement account.

Figure 3.1: the 5 bricks

Brick #1: Know what's coming in and going out

The first thing to do before you begin your investing journey is to have a very clear understanding of how much money is coming in and out of your life. Some people call it checking your cash flow, or budgeting. Either way it's important to be crystal clear about your money. One of the most common habits of financially successful people is tracking their personal finance and understanding exactly how much they spend and make in a week.

Why? Well, if you can't track something you can't improve on it. Investors in training know it's hard to work out if we're getting better or worse with our money if we don't have metrics to compare it to. It doesn't mean tracking everything on a four‐tab Excel spreadsheet, but it does mean knowing exactly how much you make and spend monthly. If I asked you what those two numbers were, would you be able to tell me?

I could suggest printing out your bank statement for last month and highlighting in one colour all the income that's come through, and then in another colour highlighting all your expenses, but that's painful. No‐one wants to do that.

Instead, I recommend doing this: get an app that tracks your spending, or even just a notebook where you can jot things down and take note of your spending and income for a week. Ideally it would be great to do this for a month, but even a week is a start.

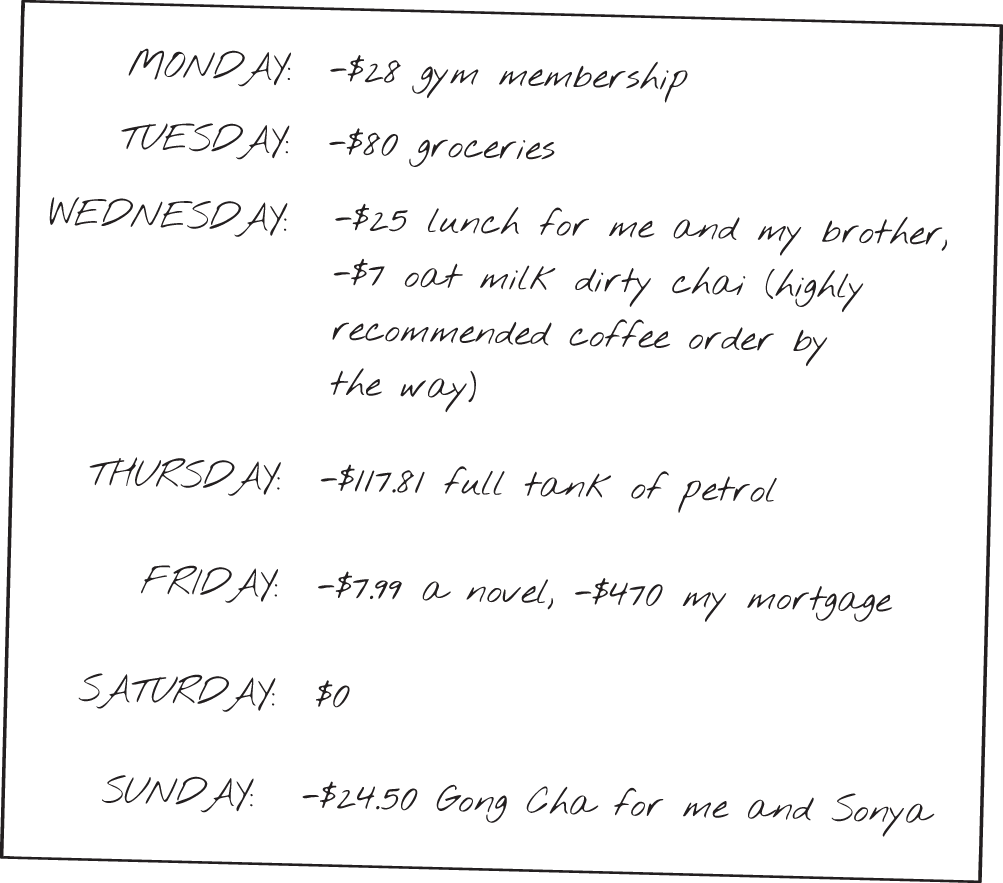

Most people know what they earn as most of us get a regular income, but not a lot of us know how much we spend. To show that the task of tracking your spending isn't that difficult, I challenged myself to note them down this week as well.

By knowing exactly what is coming in and going out, you get a better idea of what you can do with your money. For example, you may realise you spend a lot of money on things you don't actually enjoy. You may even realise that you're paying for a monthly subscription that you forgot to cancel. By knowing your cash flow, you can then get a better idea of how much you are able to cut out and rearrange, and therefore what you're left with to save and invest.

I find this to be a much better approach to money than trying to work out how much is left at the end of the week and investing that. It's so much more powerful to say that you have a set percentage per month that you put away into your investing portfolio. This gives you a much clearer idea of what you can invest after you account for everything else.

Value‐based spending

Another benefit of doing this at the start is it encourages what we call value‐based spending. It's like a budget, but rather than focusing on what you can't spend and cutting everything down to the bare bones, you get to allocate money towards the things that are important to you. This could be $300 towards skincare every year or $1000 towards travel. I've never been a fan of cutting down spending to the point where you cannot even enjoy the simple pleasures of a $5 latte.

With value‐based spending you get to allocate your money towards the two or three things that are important to you and forget the rest. For you, that might be holiday travel or getting manicures. For someone else it might be splurging on higher quality clothing that makes them feel good. The point is that there is no guilt or shame associated with spending money, and instead you're empowered by spending money in alignment with your goals and values.

This form of cash flow management is also something that you're more likely to stick to in the long term. At the end of the day, it's better to be spending in a way that is aligned with your values instead of trying to stick with a harsh budget and giving up every few days. It's not about trying to deprive yourself of the few sparks of joy you get throughout the week; it's about finding a balance in your spending and saving habits so that both parts of you are fulfilled.

There is no joy in living a life where you deprive yourself of every small joy just to serve future you.

Future you needs to be taken care of, but we can take care of them while also allowing ourselves to enjoy the moment and live in the present. Investors in training understand that when it comes to their money habits, it's all about preservation over deprivation.

So how do you do it? Once you have an idea of how much you make and what you spend on a weekly and monthly basis, it's time to examine if this aligns with your value‐based spending. Note down how much you spend on your needs, as well as your wants, in alignment with your goals.

If at this point you realise your values and spending aren't in alignment, it's time to sit down and allocate where you want to spend your money so things do start to align. Some people like to use images of things like buckets or hats. Some people like percentages. I just like to use numbers. It does the job. See table 3.1. Take out a pen and jot down roughly how much you make a month and how you’d like to split that across your wants and needs. It’ll take you four minutes at most, I promise.

Table 3.1: income allocation

| Income (monthly) | $ |

|---|---|

| Home and utilities | |

| groceries | $ |

| mortgage | $ |

| rates | $ |

| home maintenance | $ |

| internet/phone | $ |

| electricity | $ |

| water | $ |

| Insurance & finance | |

| savings | $ |

| investments | $ |

| car insurance | $ |

| home & contents | $ |

| life insurance | $ |

| health insurance | $ |

| loan/credit card repayments | $ |

| pet insurance | $ |

| income protection | $ |

| Personal & entertainment | |

| eating out | $ |

| clothing & shoes | $ |

| grooming (hair, beauty, skincare) | $ |

| gym/sports | $ |

| app subscriptions (e.g. Headspace) | $ |

| music/TV subscriptions | $ |

| holidays | $ |

| gifts/donations | $ |

| Transport | |

| public transportation fare/taxi costs | $ |

| petrol | $ |

| parking | $ |

| repairs/maintenance | $ |

| car insurance/registration | $ |

| other | $ |

| Children and/or dependents | |

| babysitting/childcare | $ |

| schooling & activities | $ |

| pet care & vet bills | $ |

| child support payments | $ |

| parental retirement aid/health (e.g. giving your parents money every month to help with their living expenses) | $ |

| Health | |

| doctor appointments | $ |

| vitamins | $ |

| medication | $ |

| sanitary products | $ |

| other | $ |

I don't quite believe in asking people to put 30 per cent into one category or 20 per cent in another. Value‐based spending means you get to decide what you do with the money you get in your account every week. You may decide to put 50 per cent into your living costs because you prefer to live in a more expensive city to be close to family — that doesn't mean you should be made to feel guilty for not keeping living expenses ‘under 30 per cent’. It's all about aligning what's on this paper with what you value in your life.

Once you get a clear picture on that you'll know exactly what you have left to allocate to investing. Someone may say ‘This leaves me with $50 left over at the end of the week, but I value holidays so I'm okay with putting $40 of that money into a savings account towards my travel fund, and putting $10 to investing.' That is fine.

You are allowed to decide that travelling means more to you than investing. We are not all the same people, and we have different life experiences and desires. It's just important to note that we can't have it all at the same time; if we want to grow our wealth faster, it's about deciding what our values are and shifting our spending and saving habits to reflect that. One person is going to feel more fulfilled by being wealthy in experiences over money. It’s too personal to generalise and shame each other on our money habits.

By having a clearer idea of where your money is going, you get to control it rather than having it control you.

Your spending habits are not an easy thing to face, but you're better off in the long term to have laid down this brick. Well done.

Brick #2: Tackle high‐interest debt

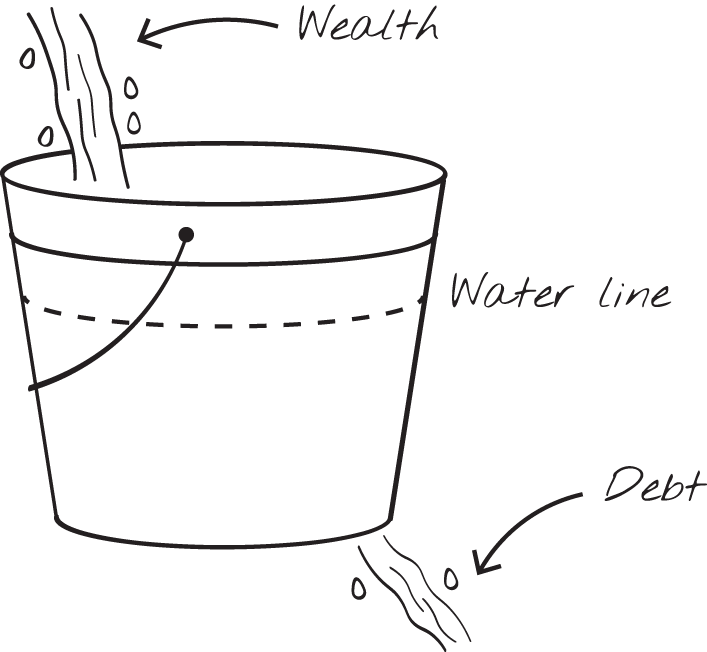

Trying to invest while having high‐interest debt is like trying to fill a bucket with a hole in it. No matter how much water you put in, whether it be from a glass or water directly from a hose, you will never be able to fill the bucket until you block the hole that's draining your wealth … I mean water. See figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2: high‐interest debt drains your bucket

High‐interest debt is the hole in your bucket. Let me explain with numbers. If you invest and get a nice 10 per cent return every year but you have a car loan or high‐interest credit card debt of the same amount that is taking 15 per cent per annum, you're not making money — in fact you're still losing 5 per cent. In simple terms, if you have $100 a month to either invest or pay off high‐interest debt, you're going one step ahead but two steps back by investing it. Getting rid of high‐interest debt is an important part of your financial wellness journey and another strong brick in your foundation.

Now, you may be wondering what kinds of debt you should be getting rid of before you invest, and what debt doesn't matter too much.

In countries such as New Zealand, student loans are usually 0 per cent interest, so it does not make sense to pay this off before you begin investing. In fact, when debt has a 0 per cent interest it almost makes sense to pay it off as slowly as possible, as $50 000 today will be worth less in five to 10 years' time due to inflation.

In some countries or with private universities, student loan debt can range from 3 to 14 per cent, and the loans themselves can be as high as six figures. Interest on credit card debt is on average around 14.5 per cent, and mortgages average around 3 to 6 per cent. So which ones do you pay off?

There is no magic number that determines what ‘high interest’ is, but I like to say that anything over 7 per cent should be paid off sooner rather than later. Why? Because the stock market usually returns 7 to 9 per cent annually, so having debt at or over 7 per cent begins to eat away at your gains. It's just like pouring water into that bucket with the hole at the bottom.

If you have debt, let's list them out:

- Student loan debt $______ at ____ per cent

- Credit card debt $______ at ____ per cent(Look, if you need multiple lines for this one, I am not judging.)

- Personal loan debt (e.g. car) $______ at ____ per cent

- Mortgage debt $______ at ____ per cent.

If any of these interest rates are higher than 7 per cent, it's worth your time focusing your attention on paying them off as soon as possible — in most circumstances, you'll feel better about investing once you have all the high‐interest debt paid off. If the interest rate is under 7 per cent it doesn't mean you cannot invest until the debt is paid off — if that were the case, no one with a mortgage would ever enter the stock market.

To get rid of your high‐interest debt, you might be able to start by consolidating or refinancing your debt. This means merging several debts into one and ideally getting a better interest rate to attack them faster. You can achieve this by contacting your bank or credit union or speaking with a financial adviser.

Snowballs and avalanches

If you're more of a DIY person, one way to tackle debt is the snowball method. List all your debt from the smallest amount owing to the largest, then tackle the smallest debts first, working your way up to the largest one. For example, if Ha‐eun had $2000 credit card debt on one card, $5000 on another and a $13 000 car loan, she'd pay them off in this exact order. This helps to build momentum and is often a good place to start for those who may feel overwhelmed.

Why you'd want to use the snowball method:

- It gives you motivation over every ‘small win’.

- Your first debt is paid off sooner.

Another way is the avalanche method, where you tackle the debt with the highest interest rate and then work your way down. In this case Ha‐eun would first pay down the loan with the highest interest rate, then the one with the second highest interest rate, and so on. This is a great method for when interest rates are higher, which can grow the debt out of control much faster.

Why you'd use the debt avalanche method:

- If interest rates are high, it stops the debt from growing quickly.

Invest or pay off that mortgage?

A common question I get is how to deal with having a mortgage and wanting to invest. Are you meant to pay off your mortgage first and then invest, or should you do both simultaneously? The short answer is either works.

The long answer is that it depends on the interest rate of the mortgage, how many years are left on the loan, and your personal preferences. Let's imagine you had a $500 000 mortgage with a 5 per cent interest rate for 30 years.

If you had a spare $1000 a month, you could top up your mortgage monthly, which would save you 12 years and eight months off your mortgage and save $212 381 in interest payments. That's a significant chunk of money and time.

Now if you invested $1000 a month for 18 years instead of putting it into your mortgage, with a conservative annual return of 6 per cent, you'd have $380 959 in your investing portfolio, which makes investing a better option than paying off the mortgage. But you'd still have 12 extra years to pay off your mortgage, and as rates change this could eat into your gains.

As a result, one could work just as well as the other depending on your personal circumstances. It's important to note that if you went the investment route, you'd also be taking on the risk of assuming the stock market would perform well over the 18 years, which, while likely, is not guaranteed.

In some countries, interest rates for your mortgage get updated on a regular basis while others can offer the same flat rate for 30 years (US, I'm looking at you). When your interest rates can change, so can your goals. You may decide to not focus on paying off your mortgage fast one year, but change your mind when you refix your new rate.

Some people (like my parents) don't like having debt over their heads and want to get rid of their mortgage as soon as possible. Some people (like me) are okay with a mortgage and instead pay the minimum, putting the rest into the stock market. Both these systems work for the people involved.

There are some situations where, regardless of money, you might prefer to pay off your mortgage first, e.g. if you're closer to retirement and don't want to have those repayments affecting your cash flow. Or wanting to free up your monthly income. At the end of the day, it's about finding what works for you.

Brick #3: Automate your money

I love automation. I love technology. It's arguably one of the best things to have happened to someone lazy like me. One of my older colleagues used to call us the button generation — where everything can happen at the click of a button, from food being delivered to our homes to ordering a taxi. I'll take it.

Our money can be automated too, and it's great. It takes away the stress of having one extra thing to do in your life, especially on days when you feel overwhelmed and have so much on your plate already. Sonya, my best friend and podcast co‐host, likes to keep money and investing as simple as possible — after all, if it's already a bit of a difficult concept to learn about, we don't want to make it even harder to do.

Once you decide that you want to invest and you have a good understanding of your cash flow, it's time to open an extra online bank account. You want to set up an automation so that every time you get paid, $X goes into this account. This is your investing account: it's where your investing money sits until you put it into your brokerage account.

For example, say you get paid $900 every week. After accounting for all your needs and wants and your savings, you have $50 left.

You'll have $50 automatically transferred every week into your investing account, and then have the money from there transferred every fortnight or month into your brokerage account to invest.

‘Why not invest weekly?’ you might ask. Good question.

Many brokers have fees associated, and while we get into fees in a lot more depth in chapter 5, for now let's say that if you're investing with a small amount, like $50 a week, you're better off saving that and investing $100 a fortnight or $200 a month to mitigate the fees. As you can tell, this rule doesn't apply as much if you're investing with a lot more money.

So rather than getting paid, spending what we want and then saving or investing what's left over, we flip the order, putting aside a part of our pay cheque for our future self every time we get paid. It's the definition of paying yourself first. Sonya calls it a form of self‐respect and I fully agree. Future you will thank you for it.

Brick #4: Make a rainy day fund

Before we begin investing it's important to have a three‐month emergency fund kept in a high‐yield savings account. This should cover three months of your living expenses; some people like to be able to cover up to six months of expenses, and I've even met people who keep up to 12 months of living expenses. How many months you have saved up will depend on your risk tolerance and what kind of work you do. For example, freelancers may save up more due to the nature of their job, while a doctor or nurse may not be too concerned about job shortages. It's important to have a savings account for emergencies only.

You can decide what emergencies mean for you (in addition to the obvious, such as sickness or loss of employment). For me it's things like:

- dental work

- private healthcare costs

- car breakdowns

- insurance excess on something stolen.

For me it doesn't include things like:

- fines or parking tickets

- unexpected travel

- upgrading (flights, tickets, etc.) last minute.

Having an emergency fund has been life‐changing for me. It's allowed me to have a level of peace in my life that I have not had before. It's a great way to make sure that I am always looked after and always have access to money. If I need to leave a situation that does not serve me, I don't have to rely on someone else to help me out.

I recommend opening up another bank account to keep this emergency fund in, preferably a high‐yield savings account that you have easy access to. Some people ask if they should invest this money; the answer is no.

Investors in training understand this isn't money you're trying to make money off; it's money that you're keeping aside but can access instantly. When you invest this kind of money in the stock market, you need to wait for it to liquidate before you can use it, and in the short term this may fluctuate, thus not giving you the full amount of money you need. It's tempting to put your emergency fund into the stock market, but that's greed taking over rationality.

Another benefit of having an emergency fund is so you don't draw down your stocks every time there is an emergency. An investing portfolio shouldn't be treated like another bank account you can pull money from every time you want to make a purchase. By pulling out your money, not only do you trigger fees, but also taxes and the opportunity cost of compound interest.

You don't want to have to sell your stocks every time there is an emergency. By having an account dedicated to emergencies, you're taking care of yourself financially. Save yourself up an emergency fund before you begin investing.

Brick #5: Sort out your retirement account

You may be in the US or UK, in India or New Zealand — wherever in the world you're reading this from, it is almost guaranteed that your employer has a government‐issued retirement scheme where your employer matches your contributions (or at least some part of your contributions).

In simple terms, if you sacrifice 3 per cent of your salary to your retirement account, your employer puts the same amount again into that account. That is a 100 per cent return on your money. It is unlikely the stock market or cryptocurrency could ever guarantee a 100 per cent return on investment (ROI).

You may be wondering what the point of this is. The government in your country understands the importance of you having a nest egg for retirement. They don't want you to be without money when you reach 65, so they will ask employers to match your contributions as a way of encouraging you to save.

People often ask how much of their income they should contribute, as most countries offer a range from 3 per cent to even 8 per cent or more. The answer is simple: contribute the minimum amount for maximum employer contribution. If your employer only gives up to 6 per cent, you only match 6 per cent. Otherwise, anything extra you add gets locked into the retirement fund.

The next step is finding out what retirement fund you've been set up with. For most of us this is usually set at a basic balanced fund. Some governments will go out of their way to choose this for you, keeping you in the most conservative fund just in case. However, a balanced or conservative fund isn't always the best fund for you.

If this is a retirement account, usually you don't need this money any time soon, so you may want to choose a growth account, or if you'd prefer less risk, then a balanced account might be a better option. The third option is for those who aren't comfortable with much risk and therefore are okay with less reward. This is when a conservative account comes in.

You may question why you should invest into these accounts when you can just invest that money in the stock market, right? It's that 100 per cent ROI that is important. Also, this money is usually inaccessible until you're 65, or at least until you have a life‐altering situation where you need money to get you through an illness. In some countries you can also pull this money out to buy your first home. The benefit of having this fund is that it acts as a literal barrier between us and our money. Sometimes it's a good thing to not have access to it and to let it compound over time until we need it.

Research which retirement option to go with, as there are so many out there. In some countries like New Zealand where it's not compulsory (unlike Australia), you may find that you're not investing into one at all, or that the one you're in isn’t aligned with the amount of risk you're comfortable with.

***

Congratulations! You now have your first 5 bricks laid out. These are going to be the foundation of your financial future. When it comes to investing in the stock market, investors in training know the importance of having these foundations rock solid before they begin. It's tempting to invest before ticking these off, but I highly recommend you take one evening this week to tick these off — you can get it done in two uninterrupted hours. Investing is a marathon, and if it's an activity you're going to do for the rest of your life, it pays to set it up right before you begin.