Appendix Essay

The Remembered Fieldwork Sites:

Impressions and Images

Since this book is constructed to delineate the dynamisms of a “system” spanning multiple countries, it does not contain much material to bring to the reader a flavor of the research sites and a sense of “being there” as most ethnographies do. For the same reason, my informants’ experiences are fragmented in different chapters to serve my thematically organized argument. To compensate for this, I attempt in the appendix essay to provide a thumbnail sketch of the typical settings—as I felt and remember them—in which I interacted with my respondents. The biographical index following this describes the life stories of my Indian informants; most of this information is not included in the chapters. For those with whom I am still in touch, the information is updated to mid-2005.

Sydney

Following what I learned from numerous anthropological studies on immigrants, I identified the Indian grocery store as a strategic “node” of the “diasporic space”—my initial research focus. Tambi, a Tamil in his forties running a large grocery in Ashfield, was thus fortunate enough to become one of my first informants. Tambi urged me to learn Tamil and asked why I had not studied IT, which, he said, had now lifted the Indian civilization to a new height. Tambi had another good reason to think highly of IT. His grocery neighbored the body shop Advance Technology Institute; students of IT training courses came down to his shop to buy snacks during breaks, and workers shopped there on their way home in the evening. In May 2001, when Tambi’s wife was ill and the family could not come to the shop every day, he hired two part-time shop assistants—both benched IT professionals from Advance Technology.

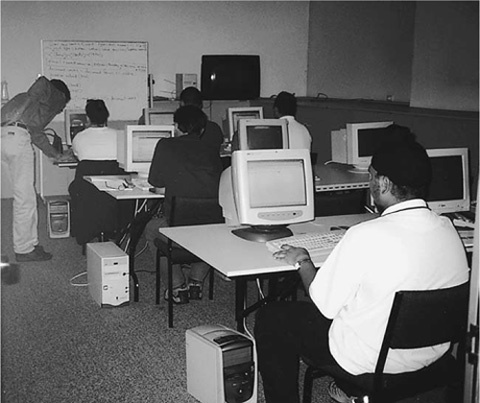

FIGURE 3. By Indians and for Indians: An IT Training Class Provided by a Body Shop in Sydney (December 2001)

I did not study either Tamil or IT, but I visited IT training classes and weekend Indian language schools frequently. The latter, originally identified as another strategic node of the diasporic space, turned out to be an important venue for establishing contacts with body-shop operators. Running weekend Telugu or Tamil schools for children was a key activity of the associations dominated by body-shop operators and other middle-aged immigrants, and chatting while waiting for the kids was the main means through which IT professionals caught up with one another. Body-shop operators who were active members in the associations took charge of the running of the class in turn, brought in tea, coffee, and biscuits to share. Their job here was, as they often said, “to serve the community.”

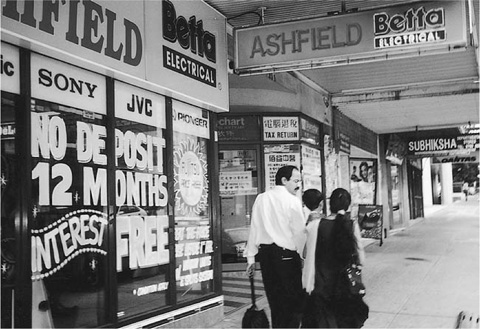

FIGURE 4. A Street in Ashfield (February 2001)

Sydney does not have clear concentrations of Telugu IT professionals, body shops, or even Indian populations in general. I did my fieldwork mainly in three dispersed areas: the central business districts in downtown and north Sydney where I lunched with IT workers or waited for them after work; the central west part where I lived with Uday and others; and the far west of Sydney. Ashfield in the central west was a favorite place for young Indian IT workers to hang around due to its convenient transport, Asian-style food courts, and, good for Tambi, Indian groceries; and many recent arrivals on 457 visas jointly rented flats in the area. Strathfield, a posh suburb in the central west, was called Strathpura (“pura” means “town” in Hindi) in the 1970s and 1980s in the Indian community because of the large number of Indian residents, particularly physicians, there. By the time of my fieldwork, about one hundred Indian families had houses in Strathfield proper, much fewer than in other suburbs. The periphery of Strathfield close to the railway station where Uday and I lived looks completely different, and the house rent was much lower. Uday never visited any Indian family in Strathpura and always asked me what the houses looked like after I returned from interviews. Finally, many body-shop operators bought or built houses for their own use, or rented flats to sublet to workers in far west Sydney (including the suburbs of Liverpool, Blacktown, and Parramatta) where real estate price is low. Quite a few body-shop offices were also located there due to the low rent.

Kuala Lumpur

I had one of the most striking encounters during my fieldwork in the Kuala Lumpur airport on my way from Sydney to Hyderabad. A young Telugu IT worker, being told that transiting passengers could stay in Malaysia without visas for seventy-two hours, had flown in with a return ticket from Melbourne, hoping to zoom around and get a job in Kuala Lumpur within this time. It was only at the immigration checkpoint, where we were both queuing, that he found out that the seventy-two-hour-stay only applied to passengers heading for a third country; he could not even leave the airport and had to take the very next flight back to Melbourne, where he had been benched for the previous four months. With all seriousness, he asked me whether I could “get a break” for him in China.

This unlucky Telugu was one of the many Indian IT workers coming to Malaysia to look for jobs, mostly on business or social-visit visas; and there were so many such that they had become a special target of local police for demanding bribes in Kuala Lumpur. A friend of Rejeshekhar (whom I contacted through the Internet from Sydney) told us of how he was stopped by a policeman on the street who asked for his passport and work-permit card; when he said he did not have the documents with him, the policeman asked: “Are you here on business visa?” He said yes, and the policeman shouted immediately: “You are working here, right?!” The friend insisted that he was not (the business visa does not allow the holder to be employed in Malaysia), and the policeman asked him to “walk with” him—implying that he was in custody. The friend stopped the “walk” with a payment of MYR 600 after some bargaining. He cried for two days—he had worked for only less than two months and was now deprived of all his savings.

While IT workers from India were busy hunting for jobs, the Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC), the third biggest national political party, was also preoccupied with IT, but for a very different reason. Since no election was scheduled in 2001, the party identified Tamil Internet 2001—an international conference to promote Tamil Internet and Tamil computing—as a priority for that year. In conjunction with the conference, MIC planned a nationwide Net for Life campaign to help the Indian community in Malaysia equipped with IT, and an international exhibition DuniaWeb 2001 to showcase Internet technologies, products, and services from Malaysia, Singapore, the Indian subcontinent, and other regions. One of the key sponsors of Tamil Internet 2001, a large IT company with the Multimedia Super Corridor status, had over 80 per cent of its workforce from India (interviews with three MIC cadres, June 2 and 3, 2001).

FIGURE 5. A Bedroom Shared by Four Telugu IT Workers in Palm Court (June 2001)

Hyderabad

Upon arrival in Hyderabad, I was immediately advised to visit Aditya Enclave on Ameerpet Road, a residential complex built in 1993 but basically occupied by small IT consultancies by 1998. When I was taking photos of the numerous banners of advertisements for software programs, training courses, and job placements covering the building, I was stopped by a security guard in uniform and escorted to a telephone shop to see the owner—who was also the president of the Enclave Residents Association. Intervention by a security guard of this kind is very rare in Hyderabad. It transpired that the IT consultancies in the complex had set up the association to supervise cleaning and security staff—concern about security seemed to be an indispensable part of the portfolio of IT companies worldwide even before September 11, 2001. After a brief investigation of me, the president told his story. The president, an electrician, bought a shop space on the ground floor in Block B of the Enclave in 1993 to run his electronic contract business. In 1996, with the advent of IT consultancies and IT people to the Enclave, he converted the shop to a telephone booth cum Internet café. At the same time, he bought another shop across the road (outside of the Enclave) to provide services of photocopying, graphic design, and printing, almost exclusively catering to the needs of IT consultancies and training institutes to inundate passengers and students with brochures and handouts. The Enclave has thirty-two shop spaces in each block, and many of them had changed from clinics, pharmacies, groceries, and clothing stalls to businesses related to IT or emigration, such as photo shops for passport shots and bookshops selling maps.

FIGURE 6. The Façade of Aditya Enclave on Ameerpet Road, Hyderabad (July 2001)

The colonialization of the Enclave by IT consultancies ballooned the resale price of a flat from INR 8 lakhs in 1993 to INR 14 –15 lakhs by the late 1990s, and the monthly rent from INR 4 –5,000 for 1,000 square feet to INR 8–10,000 over the same period. The global market slowdown—about five IT companies in Block B closed down in the first half of 2001—however, did not bring down the price at all because the slowdown also forced many companies to move from more expensive areas, such as the Begampet district, to the Enclave. More Internet cafés were also set up catering to the needs of unemployed IT people when some IT training courses and consultancies died out. Encouraged by the price hike, the developer of the Enclave invested in 2001 in two more residential complexes in the same area targeting NRIs. The inflation of the real-estate price in Hyderabad was however only moderate compared to that of Bangalore: a few non-IT residents from Bangalore complained to me that the city had become so expensive because of the IT industry that they had to either move into IT or move out of the city!

FIGURE 7. Cyber Tower, the Main Building of HITEC City (August 2001)

FIGURE 8. A Typical House in Jubilee Hills (August 2001)

Aditya Enclave has its main entrances at Satyam Camine Talaies Road off Ameerpet Road, a narrow street about eighty feet long hosting twelve big training institutes in 2001—one of them had 450 students every day. The large crowd brought about vibrant businesses. A couple of studentrecruitment agents for overseas universities (particularly for those in Australia and New Zealand), for example, moved in from elsewhere, as one agent owner explained: the unemployed IT “floating people” in the area provided ideal potential clients. Indeed, many long-term potential emigrants went abroad as students after failing to find jobs both in India and overseas. I also ran into a neatly dressed young man busy with market research for his business plan of delivering services to the families left behind in Hyderabad by IT NRIs for a charge of USD 25 a month—a price decided “scientifically” based on his interviews with potential IT NRIs. He had no doubt about the prospect of the plan—by buying his services, he reckoned, the overseas IT son could show both social status and filial piety to the extended family—and the idea would be worth millions of dollars if he had access to VCs (venture capitalists) in the United States. Ameerpet was not all about business and IT though; there were also corners of romance. I was asked by a couple of male students to approach female classmates, and a female teacher on one occasion, to pull strings on their behalf.

FIGURE 9. Visu Consultancy in Bhimavaram (August 2001)

The “real” IT place in Hyderabad, however, as most of my informants contended, is the HITEC City in Madhapur district. Standing for Hyderabad Information Technology and Engineering Consultancy City, HITEC City is the largest IT industry park in India, offering “world class state-of-the-art IT infrastructure,” as described in numerous official and corporate documents. A showcase of “Cyberabad,” HITEC City was even touted as a tourist site in official brochures of Hyderabad and Andhra Pradesh. Adjunct to HITEC City is Jubilee Hills, a suburb chock full of Southern California–style mansions, many belonging to successful IT people.

Rural Andhra

My field research itinerary almost exactly reversed the typical journey of a Telugu IT professional: starting from Sydney, transiting in Kuala Lumpur, and then Hyderabad, before the final leg in villages in coastal Andhra. The sense of “reversal” came to me particularly strongly when I passed auto-rickshaws ferrying two or three schoolchildren, in most cases boys, on my way to villages. They were usually from upper-middle-class families and were commuting to their private schools in town from home villages. While education at government village schools (panchayat union elementary school) is free, private schools in town cost approximately INR 500 per month, and private intermediate colleges (ages eleven to twelve) INR 25,000 per year (including expenses). The singular attraction of private schools is that the courses are taught in English—instruction in government schools is in Telugu. Coastal Andhra, as one informant put it, is “education rich.” Bhimavaram, a town with a population just over 140,000, had about twenty private schools. Some villages, such as Peuugonda (about twenty-two kilometers away from Tanuku town), have their own colleges. According to a lecturer at the locally prestigious West Godavari Bhimavaram College, the education quality of colleges in the coastal districts was no lower than in Hyderabad, and people moved to the capital mainly for the lifestyle and to go abroad.

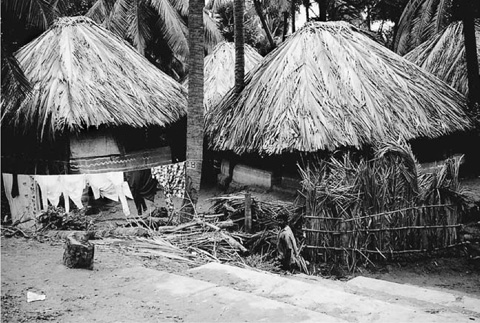

FIGURE 10. Kachcha Houses (Mud Huts) in a So-called Low-Caste Area in a West Godavari Village (August 2001)

But the chances of going abroad directly from coastal districts were in fact higher than people usually thought, as pointed out by Vasan, the twenty-six-year-old owner and operator of the Bhimavaram franchise of Visu Consultancy, a large training institute cum IT consultancy headquartered in Hyderabad. Vasan’s key business was coaching for Toefl (the Test of English as a Foreign Language) and GRE examinations, but the consultancy also provided IT training and had recently started body shopping by linking with agents in Hyderabad. Quite different from what I assumed, often it was Vasan who provided the leads for overseas jobs—capitalizing on his connections with a large number of IT professionals overseas originated from Bhimavaram—and his Hyderabad associates handled the paperwork. In two cases his Hyderabad associates even placed workers in the United States through his connections!

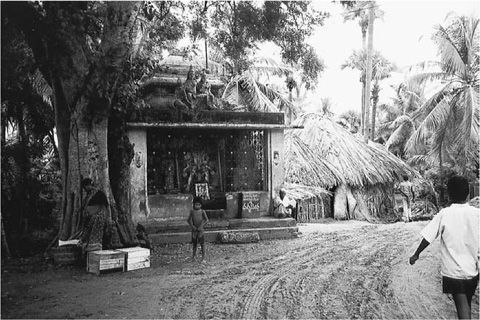

FIGURE 11. A Corner of a Village (August 2001)

How Vasan had set up the franchise provided another example of how my journey reversed that of the IT people’s. Vasan’s parents in a village near Bhimavaram had been farming a 54-acre prawn tank, (a man-made pond [often raised from the ground] for prawns), including 4 acres of their own and 50 leased at a rent of INR 20,000 per acre per year. They had to borrow money from private lenders at the interest rate of 24 percent per year—a common practice for farmers in this region since they did not have enough security to take bank loans, and big landowners hardly invested in agribusiness. Partly due to the lack of capital, the family, like other farmers, could not sustain the quality of prawns (which were mainly exported to the United States and Japan), and consequently the price dropped from INR 460 per kilogram in 2000 to INR 240 in June 2001. Losing confidence in agribusiness, the family decided to follow the global trend to IT, and invested INR 5 lakhs to set up the consultancy.

In Tanuku and Bhimavaram I made a few friends quickly, mainly students of local colleges, and I followed them to their home villages. Mahathi, one of them and a second year undergraduate student in English, looked reluctant when I suggested a cup of tea when passing a small tea house at the junction of his home village and the main road. His reluctance made sense only when I learned, later, that Mahathi and his fellow caste members, of the so-called low categories, were not supposed to enter the tea house and could drink outside only. The village is divided into three or four streets with completely different houses and facilities and with clearcut boundaries between: good streets for the so-called high caste, and bad for the so-called low ones.

In a marketplace in Tanuku, I ran into a former member of the Communist Party of India (Marxist). After learning that I was from China, he ordered his nephew, a shopkeeper, to sell me the cotton kurta that I liked at the price he’d purchased it at. He also gave me the contact information for one of his comrades, a retired school principal now residing in a village close to Tanuku. After a long talk about political philosophy, world affairs, and the complex relations within the communist movements in India, the former principal dispatched his granddaughter, Rani, a master’s student in chemistry, to show me the village. Rani took up the assignment happily but when we walked into a different street, her steps became stiff, her face red, and her head bowed: the street was suddenly full of widened eyes. Rani told me that as a Kamma woman (Kammas had been the dominant group in the Communist Party of India in Andhra Pradesh, particularly in the later Communist Party of India (Marxist), and communism in Andhra was thus once dubbed Kammanism), she was not supposed to walk in low-caste streets since it would pollute her. Although for brave young people like her, walking through was no longer an absolute taboo, changing residence across streets is still unthinkable. Low-caste families with professionals or well-off emigrants could not move to high-caste streets with better infrastructures, and thus migrating to towns and cities became a more feasible option.