Chapter 2. Superior Searching

Searching the Web is like panning for gold. There’s a lot of dirt out there, and you need the right tools to get at the shiny nuggets. The previous chapter provided the sieve. But to become a real search jockey, you need tweezers. And forceps. And maybe a staple gun.

It may help to think of every search as a problem, and to bear in mind that different problems require different solutions. “How do I find out which Web sites link to mine?” needs a different approach than “I want to find sites about Miss Piggy—but only those in Urdu.”

This chapter sets you up with an array of techniques that you can use to run different kinds of searches or get more specific results from any search. Because Google’s preference settings can affect all of your results big time, this chapter covers them, too.

Have It Your Way: Setting Preferences

Software programs almost always let you change some settings, like the way Microsoft Word lets you choose the standard font or turn spell checking on and off. Google lets you set some preferences, too. Unlike Word and other programs that hang out on your hard drive, Google remembers your settings with a cookie, a tiny file that a Web site can place on your computer and communicate with.

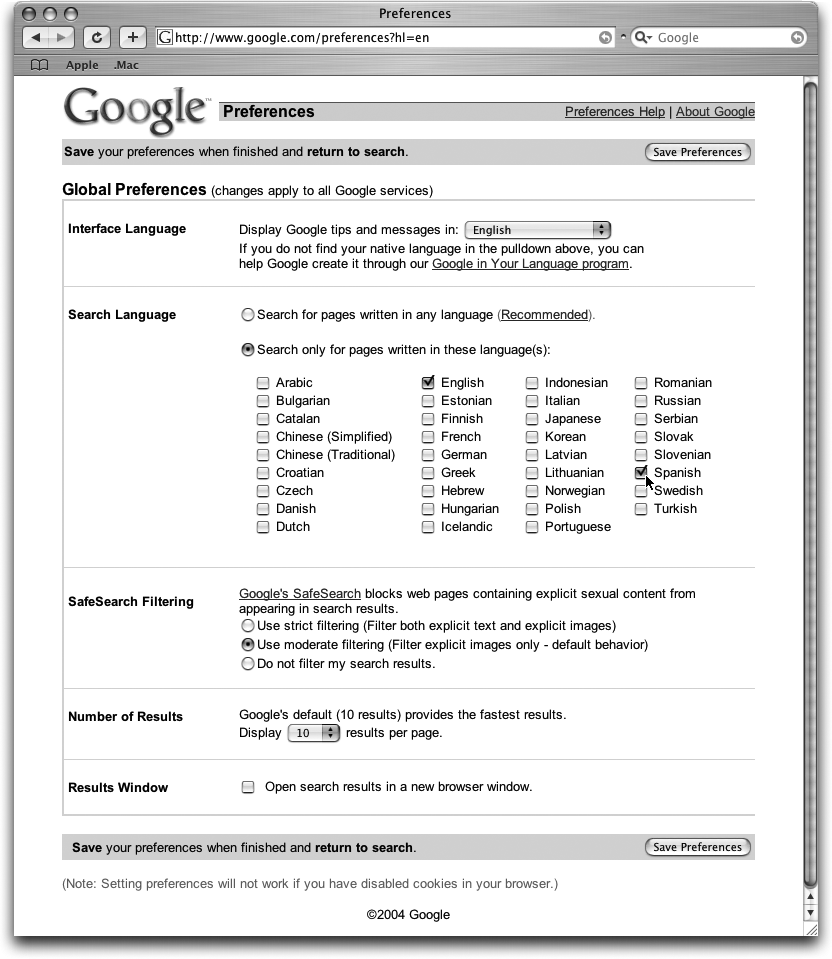

You can reach Google’s settings page by clicking Preferences on the home page or at the top of any results page. Figure 2-1 shows the Preferences page, from which Google lets you control five settings: interface language, search language, filtering, number of results, and which window the results appear in. You have to click Save Preferences to activate the new settings.

Tip

If you change your settings and return to Google only to find they didn’t take, your browser could be set to reject cookies. Check your browser’s security or privacy settings. In Internet Explorer, for example, choose Tools → Options and then click the Privacy tab. You can move the slider to change the intensity with which the program blocks cookies (anything below the highest setting works for Google). Or you can click Edit to specify a Web site from which you want to allow cookies—in this case, www.google.com.

Interface Language

The interface language controls the language Google uses to display tips and messages. Google sets itself to use English, but you can change it to anything from Afrikaans to Zulu. If you want to add some zing to your Google experience, try Bork, bork, bork! (the Swedish Chef), Elmer Fudd, or Hacker. For the less adventurous, Google provides Tamil and Scots Gaelic.

Search Language

The search language is different from the interface language. Instead of affecting the way Google talks to you, the Search Language limits your results to pages that are written in the language you specify. Google assumes you want sites in any language, but if you’d prefer sites only in Finnish and Catalan, this is the place to say so. Just click the blank box next to a language.

The tricky part is that this setting really, really limits your results. Unless you know for certain that you always want to search in one language, you’re probably better off using Google’s Language Tools (Section 2.4) to fine-tune individual searches.

SafeSearch Filtering

It’s no secret that the Web is home to a lot of explicit text and pictures. If you want your search results to avoid some or possibly all of that material, you can filter it out with SafeSearch, which has three modes:

Moderate filtering usually works fine for most casual Web surfers. Because Google tries to give you the most relevant pages first, a search for breast cancer or impotence is unlikely to yield inappropriately salacious results in the first few thousand listings when you’ve got moderate filtering on. But occasionally, moderate filtering can cause you to miss something important. If you don’t mind surprises every now and then, turn the filtering off. Those of you who want particularly spicy content, or none at all, know who you are.

Number of Results

Google is set to display 10 results per page. Studies have shown that most people never click past the first page of results on any search site. You can increase your changes of finding your Holy Grail if Google shows you more results at once: just change the setting to 20 results per page.

Results Window

Unless you tell it otherwise, Google displays your results pages in the same browser window where you ran your search. So when you click a link on the results page, Google replaces your results list with the page you’ve decided to explore. But when you turn on “Open search results in a new browser window,” Google leaves your results page intact and starts up a new window in your browser when you click a result. (After it’s opened the second window, Google doesn’t keep opening new windows when you click results links; it just switches what you see in the second one.)

Note

If you’re using a browser with tabs (Section 6.2.2.2), this setting may make your search results open in a new tab, rather than a new window altogether.

Google comes with this setting turned off, but it’s a great one to turn on, as it lets you use one window to view the Web pages you’ve found and the other to keep track of your results. If you often explore more than one result, or if you find yourself clicking deep into sites or following links to new pages, this setting can save you a lot of hassle getting back to your results. (If your computer is getting geriatric and struggles to keep open a lot of windows, then leave this setting off.)

Advanced Search

On every Web page it tracks, Google records a handful of things, including the URL, body text, links to other pages, files in particular formats, and other goodies (Chapter 1). A simple Google search tells you when those things exist on the pages in your results. But if you want to restrict your search using those nit-picking criteria—to find only PowerPoint presentations for the terms you’re using, for example—you may feel lost.

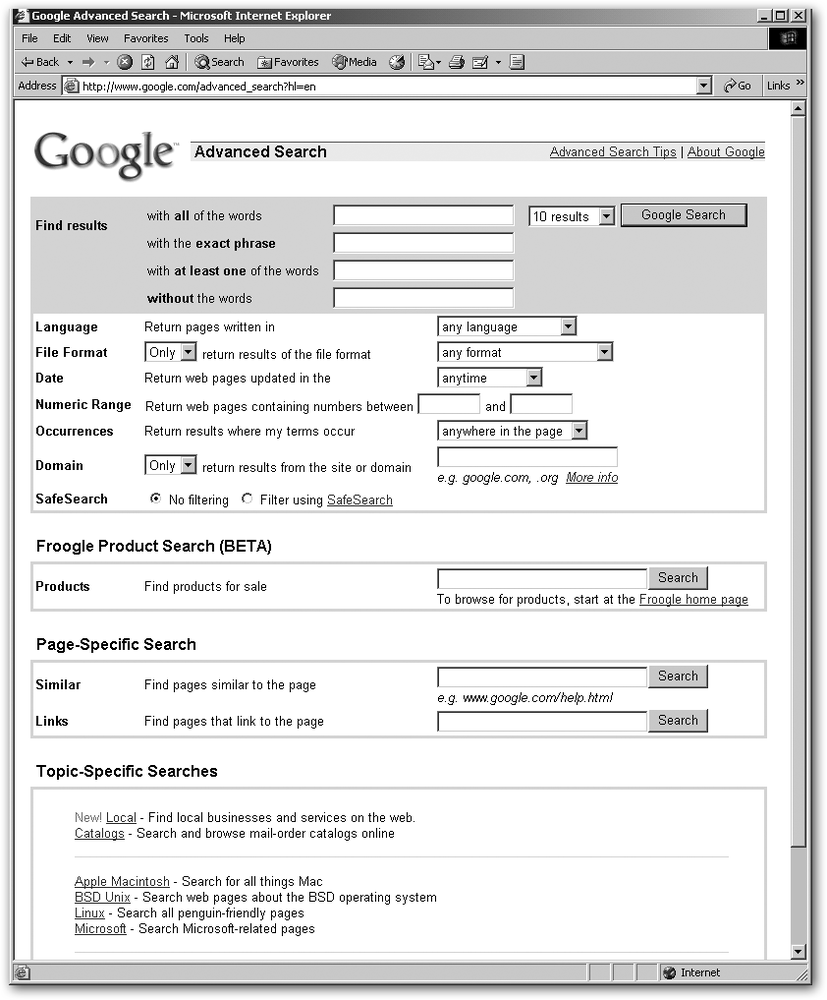

Google’s Advanced Search page can help you sort things out. You can get to it by clicking the Advanced Search link on Google’s home page or at the top of any results page. Figure 2-2 shows the straightforward form.

Refining Your Search

Advanced Search can be a quick way to build a complex query. It’s particularly handy when you want to run a multipart search—like one that looks for either Ren or Stimpy, but returns only results that are also in PDF format.

Tip

Occasionally, multipart queries from Google’s Advanced Search page simply don’t work. If that happens to you, consider using special Google syntax (described in detail in Section 2.6), which is sometimes more flexible. For example, the keyword define, followed by a colon and another word (as in, define:vintner) tells Google to search for a definition of the second word (in this case, vintner). Other syntax features let you restrict your search by file type, language, and so on.

Query words

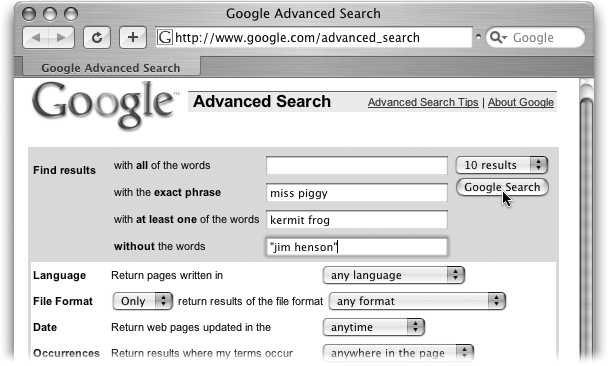

At the top of the page, in the shaded gray section labeled “Find results,” Google gives you four choices for how you would like it to treat your search terms. In order from top to bottom, these mimic the results you can get by using the operators AND, quote marks, OR, and the minus sign. The helpful thing here is that you can use these puppies in combination—which is nice when you want to do something like search for two phrases simultaneously, or search for one and exclude the other. Figure 2-3 shows one possibility.

Language

The language menu lets you specify whether you want your results to include pages written in any language, or just one particular language.

Tip

The language tools explained in Section 2.4 give you a lot more control over this feature.

File Format

The cool thing about the File Format option is that not only can you search for specific file types, like Word or PowerPoint documents, but you can exclude them, too. If you’re looking for an example of a table of contents in any format other than PDF, this is the place to let Google know.

On the other hand, this Advanced Search feature lets you specify only PDF, Postscript, Word, Excel, PowerPoint, and Rich Text Format. It doesn’t let you choose from the many other file types Google indexes. For those, you have to use the filetype syntax, described in Section 2.6.9.

Date

The Date option lets you limit your search results to pages that Google has recorded in the last three months, six months, or year. This search has nothing to do with the date a page was created, but rather when Google indexed it. (For an explanation of Google’s indexing process, see Section 8.3.) If you created a page on March 15 but Google didn’t record it until August 29, for example, it shows up in a date search for August 29.

Note

Google rerecords pages regularly—usually every few weeks. But if a page’s content doesn’t change from one recording to the next, Google doesn’t update the index date.

So what’s the use of this feature? Google indexes the Web regularly enough that specifying a range can help filter out irrelevant results. If you’re wondering what Lance Armstrong has been up to since the Tour de France, try searching for pages indexed in the last month (or however long it’s been since the Tour).

To zoom in on any date range beyond the last three months, six months, or year, see the box in Section 2.6.9.

Specifying where on a page to search

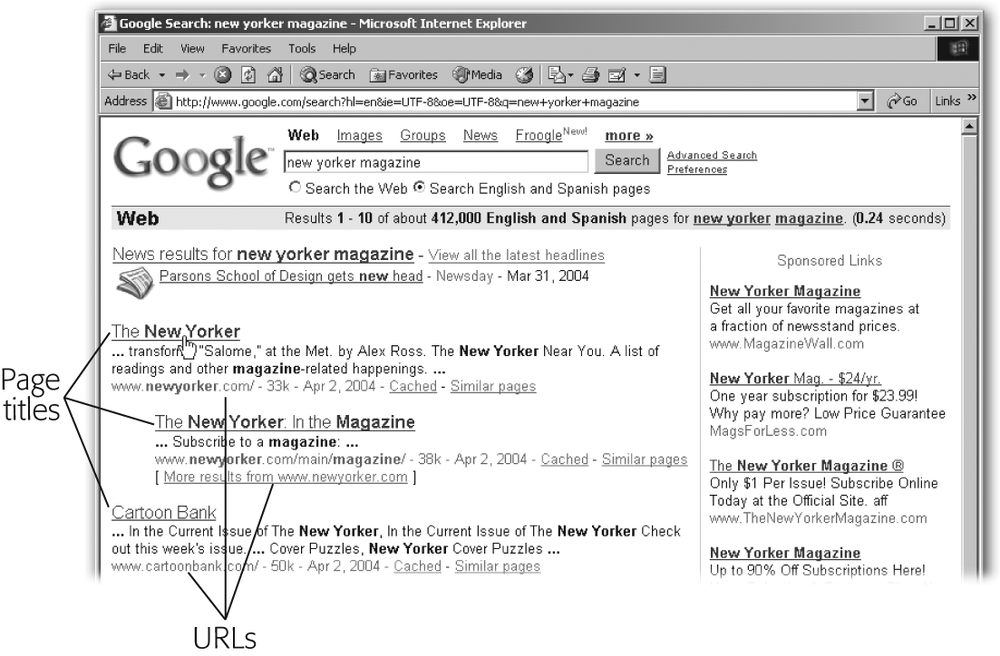

Google keeps track of text in the body of a page, in the URL, in the links to other pages, and in the page’s title (which is different from the URL). The Occurrences pop-up menu lets you tell Google when you’re looking for results from only one of those places. Here’s when you may want to use them:

In the title. A Web page’s URL isn’t the same thing as its title. A URL is an address that your computer can read, and sometimes you can read, too (for example, www.npr.org). But often, URLs are super-long and contain a slew of characters and symbols that make no sense unless you’re a droid. In those cases, it’s useful when a page has a separate, readable title that a Webmaster has written to help you understand what’s on that page. The first line of a Google result is usually a page’s title, for example, as Figure 2-4 illustrates.

Figure 2-4. Titles and URLs usually say different things, though sometimes a URL is the title for a page. When you click a title, it takes you to the page for the URL listed.A word that’s mentioned in the title of a page is more likely to indicate what’s on that page than a word that shows up randomly in the text. For example, a page called “File sharing for fun and profit” is more likely to explain how to go about file sharing than a page that simply mentions the topic as part of a side discussion. Use this feature, therefore, to get a smaller, more focused list of results.

In the text. Asking Google to ignore titles, URLs, and links is useful when you want to search for keywords or phrases that are likely to show up all over the place. For example, if you want only sites that discuss those bumpkins known as yahoos, and you don’t want pages from Yahoo.com or links to that site, use this feature to help filter out references to the Web site.

In the URL. Want to find out how many sites have already used the word “sneaker” in their URLs? Here’s the place to check. Happily, this feature doesn’t limit you to simple Web addresses, like www.sneaker-nation.com; it also gives you back more complex results, like www.cynosure.com.au/isp/sneaker.

Note

Searching for a term within a URL yields only results with whole words. In the example above, Google would give you back www.sneaker-fetish.com or www.sneaker.fetish.com, but not www.sneakerfetish.com.

In the links. This feature simply searches for the text in hyperlinks that connect pages. It’s useful in two situations. First, if you want to find out what pages have links to a certain person, phrase, or site, the “in links to the page” option can give you a rough idea.

Note

The text of a link may have nothing to do with the page it links to. Most commonly, you see sentences like, “To read about Barry Bonds, click here.” If “here” is the text for the link, your search for Barry Bonds isn’t going to bring up this page; only a search for here would do it—but since tons of Web sites use the word “here” in their links, you’re very unlikely to find what you want that way.

Second, the links search can help you find a person’s email address because on most Web pages, an email address is a link. If the person’s name is part of the email address, or if the page says something like, “For more information, email Brad Pitt,” you’re in business.

Domain

The Domain feature lets you restrict your search to a single site or to a domain (like .edu or .com). The site restriction is useful when you want to look up specific keywords on a site that has no search function (or that has a lousy one). It’s also good for a site whose search function is seriously annoying—maybe it displays results confusingly, or it doesn’t let you use the OR operator. And sometimes a Google site search turns up goodies you simply can’t seem to reach through a regular on-site search. To see the difference, try running a query with NYTimes.com as the site, and then try the same search terms using the New York Times’ own search feature.

Note

The site search doesn’t search related Web sites. For example, if you want to search all of Google’s sites, restricting your query to Google.com means you’ll miss anything in www.answers.google.com, http://labs.google.com, and so on. To make sure you hit those sites, too, try searching for Google in the URL, described above.

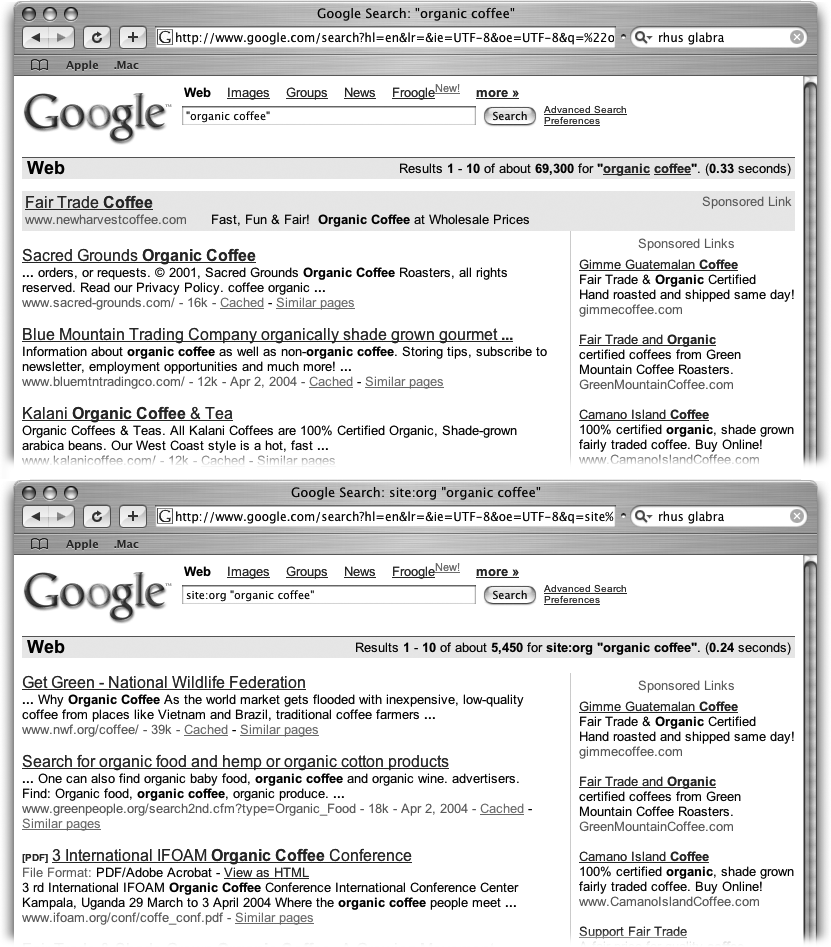

Limiting your search results to a particular domain can help, for example, sift out sites that want to sell you things. Figure 2-5 shows you what a difference it can make to limit your results to the .org domain—thus filtering out the common .coms and other flotsam.

The domain option also lets you rule out a particular site or domain—handy if your results are overwhelmed by one site that you know doesn’t contain the info you want.

SafeSearch

As described in the discussion of preferences in Section 2.1.2, SafeSearch lets you filter out offensive content. If you normally keep it turned on, but you want it off for a single search that may suffer from filtering (like bra sizes), you can make the change here.

Page-Specific Search

Google lets you run two special searches for any particular page.

Similar

When you type a URL in the “Similar” box, Google searches for pages in that general category. For example, the pages related to www.nascar.com are parts of sites like NFL.com, MLB.com, NBA.com, ESPN.com, PGA.com, and so on.

Note

The Similar feature runs the same search as the “Similar pages” link that shows up in a Google result (see Section 1.4.1.8).

Links

If you have a Web site, you could spend fully half your waking hours wondering who has linked to your pages. Just type in a URL here, and Google spits out a list of pages linked to it. (Obviously, this works even if the URL isn’t for your own site.)

Topic-Specific Searches

Your first two choices here, Google Print and Google Scholar, take you to the search pages for those specialized Google searches, described in Section 3.5 and Section 3.5.1, respectively.

Below that are links for a few broad categories in which Google has already done a little filtering for you. These topic-specific searches are all just common subsets of the Google database and help keep your searches focused. From Apple Macintosh to the U.S. Government, the topics are self-explanatory. The link for Universities takes you to a page with a handy alphabetical listing of school sites Google has recorded.

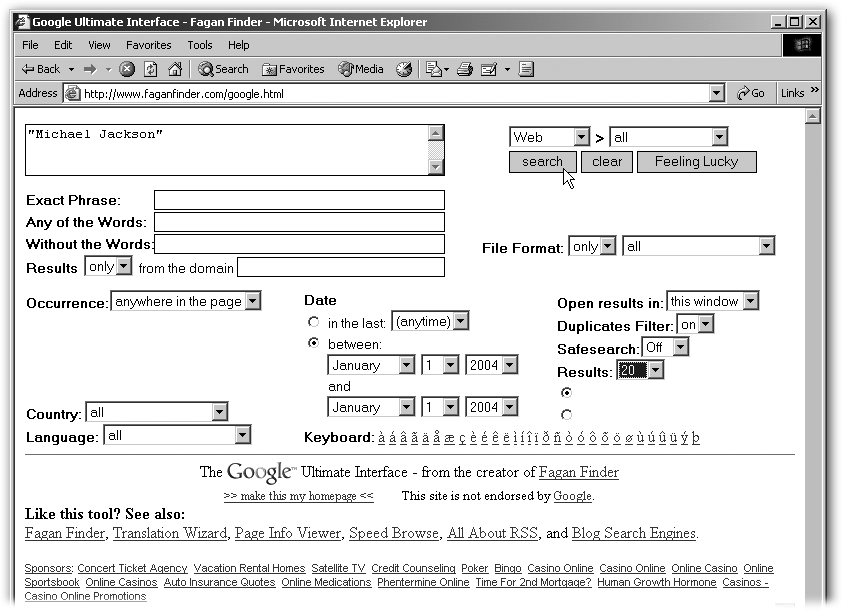

Advanced Search on Steroids

Google provides a useful advanced search form, but you can also run more specific searches from Fagan Finder, a site that has no official relationship with Google (Figure 2-6). It works best from Internet Explorer (www.faganfinder.com/google.html), but an alternate version that works with other browsers is well worth a try, too (www.faganfinder.com/google2.html).

Fagan Finder has all the choices you can specify on Google’s advanced search page—things like the type of file you want to find and the domain you’d like to restrict your search to. But unlike Google, Fagan Finder has put several other variables on the same page, letting you run a highly specialized search without using syntax or multiple searches. The extra choices include:

A menu that lets you specify the type of Google search you want to run (it’s above the Search button). For example, you can search Google’s Directory, Groups, Images, News, Catalogs, Froogle, or a few other oddball Google types (the Alternate option lets you run your query on other search sites, like Yahoo). What makes Fagan Finder’s system notable is that one page lets you run an advanced search in any of these special collections; on Google’s site, each special collection has its own advanced search page, forcing you to recreate your search if you want to check in on several areas. And Google’s advanced search pages don’t include as many detailed choices as Fagan Finder’s.

A menu that lets you specify subsets of the Google search you want to run (it’s above the Feeling Lucky button). For example, if you’re searching the Web, you can choose to run your query through Google’s keyboard shortcut page (choose “all-shortcuts”) so you can navigate your results without a mouse. Or you can choose to search just Google’s own site (handy if you’re looking for help on a particular feature), or a bunch of other narrow slices of the Web. For each type of Google search, the subsets change (the Directory search, for instance, lists the categories you’d find on Google’s main directory page), but note that not all searches have subsets (News, for instance, has none).

The country from which you’d like your results to hail.

A specific date or date range for your results. Google lets you give a general range, like “past three months.” Like Google’s date feature (on the Advanced Search form), this option searches for pages that Google indexed or re-indexed within the period you specify.

Special characters, handy for quests in languages other than English. When you click a letter on the Fagan Finder page, it appears in the general search box.

The ability to turn off the duplicates filter. You may have noticed that from time to time when you run a search in Google, your list of results is rather small, but Google inserts a message at the bottom that says something like, “In order to show you the most relevant results, we have omitted some entries very similar to the 5 already displayed. If you like, you can repeat the search with the omitted results included.” Google gives you this option because it automatically represses sites it thinks may be duplicates. Fagan Finder lets you run a search with this filter turned off from the start, which is useful if you frequently click to see the omitted results message in Google.

A choice to open results in the same window you’re already in or in a new window. Google lets you set this option on its preferences page (as explained in Section 2.1).

Note

The Fagan Finder Google page has an I’m Feeling Lucky button. Mostly, you don’t need this for advanced searches, but if you make Fagan Finder your home page, it’s nice to have the Lucky choice available.

Fagan Finder has a mess of non-Google features worth exploring, too. Head over to the home page, www.faganfinder.com, for a full menu of search tools.

Searching by Language and Country

Google’s Language Tools are a collection of features that let you fiddle with the language and location of your search. For example, you can limit an individual search to pages written in a particular language or pages from a country you specify. You can also translate text you type or entire Web pages. And you can try out a new interface language or run a search from a Google site in another country.

To find these features, click Language Tools on Google’s home page or any results page, or point your browser to www.google.com/language_tools. Here are the tools and what you can do with them:

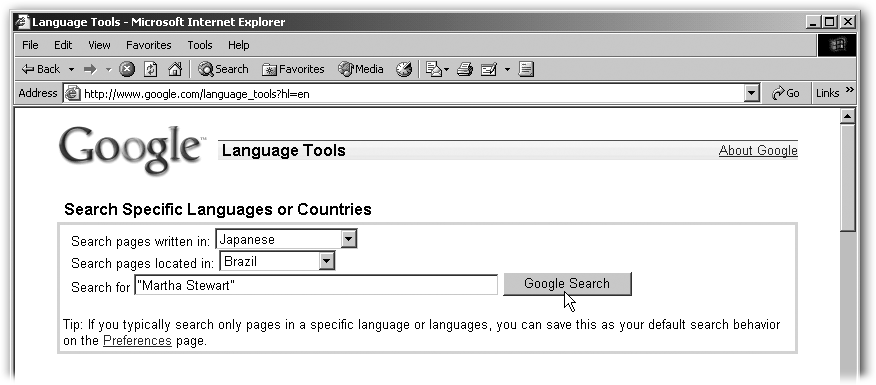

Search Specific Languages or Countries. This feature, shown in Figure 2-7, lets you narrow a search to pages written only in a certain language, with or without limiting it to pages from one country. If you’re looking to learn what Korean students at Bulgarian universities have to say about American pop stars, this is the tool to use.

Note

This feature is like any advanced search on Google: it works for just one search. If you always want to search for pages written in a language other than English, change your Google preference settings, as described in Section 2.1.

Figure 2-7. Use the menus to change either or both choices, type in your search terms, and then press Enter. When Google says, “pages located in,” it means a page whose URL specifies a country, like www.amazon.fr, Amazon’s site in France. You can find a list of URLs by country at the bottom of the Language Tools page (see the chart called “Visit Google’s Site in Your Local Domain”).Translate. You can type in a single word or lots of text into the “Translate text” box. Use the menu to choose the languages you’re translating from and to, and then press Translate to have Google display your results in a box like the one in Figure 2-8. Alternatively, you can type a URL into the blank box below “Translate a web page,” choose the languages you’re translating from and to, and then press Translate to have Google show the original Web page with its text in the new language.

Tip

If you run a regular Google search and your results include pages in languages Google can translate, it provides a “Translate this page” link next to the title of any page it can convert for you.

Google’s translation feature, like nearly all computerized translation tools, is pretty crude. After all, a machine doesn’t know that when you want to translate an Italian newspaper page about New York Mets catcher Mike Piazza, you’re not actually looking for a story about Mike Public Square. And grammar can take a hit, too. A recent page from a German site on Michael Jackson comes out like this: “In order to become fair the music-historical value of the sieved child of the family Joseph Jackson, one can either good chronologically precious metal honors list or the absolute high point of its work with a superlative on the point bring: Thriller.” As it turns out, ABC may not be easy as 1, 2, 3.

Figure 2-8. After you’ve translated something, you can search for the translated text simply by clicking Google Search on the translation-results page.Still, the translation tool can be helpful. It can give you the gist of a page in another language, and it can usually give you reasonable interpretations of single words or phrases.

Tip

If Google’s translation tool doesn’t include the language you need, try http://babblefish.com/babblefish/language.htm.

Use the Google Interface in Your Language. Like Google’s preferences page, this tool lets you pick the language in which Google displays buttons, messages, and links (it has nothing to do with the language of pages on the Web). If you pick an interface language here, however, it lasts only for the current browser session—a good way to check out the different options. For a permanent change, select your interface language from your preferences page.

Note

If you don’t see your favorite lingo on the list of interface languages, you can volunteer to translate for Google. Check out https://services.google.com/tc/Welcome.html for details.

Visit Google’s Site in Your Local Domain. Google runs sites that are primarily for searching pages whose URLs specify a country, like www.yahoo.co.jp, Yahoo’s site for Japan, and for searching sites in a country’s local language. This feature is helpful if you’re going to, say, Bilbao, and you want to find only Spanish pages about the Guggenheim Museum there.

Like the interface tool, this domain choice lasts only as long as the current browser session. If you close the browser and then reopen it, you’re back to your earlier settings. To make a permanent domain change, you must install the Google toolbar if you haven’t already done so (Section 6.1). Then click Options to open the Toolbar Options dialog box, and at the top of the Options tab, choose your domain from the menu labeled “Use Google site.”

Searching by Town

Being able to limit a search to sites from a particular country can help you filter out a lot of noise. But Google actually lets you limit searches to pages about a particular U.S. town—which is a total godsend. Whether you’re looking for a neighborhood magician to perform at your cat’s birthday party or for a bed-and-breakfast that takes pets in a town six states away, Google Local can be your online Yellow Pages.

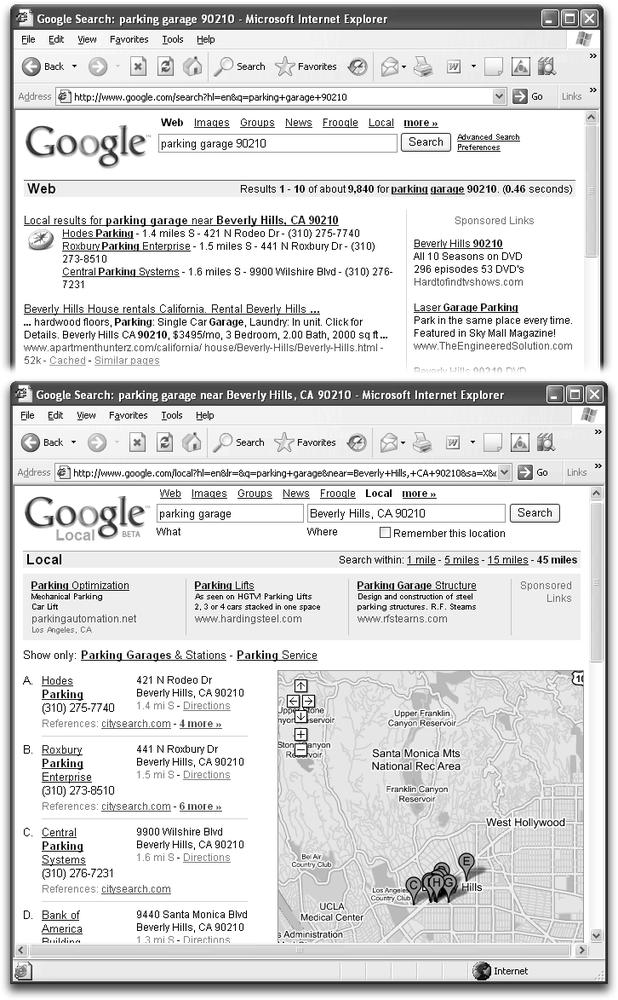

In fact, Google Local is a hybrid of the Google index and standard phonebook data. When you include in your search an address with city and state or Zip code, Google cross-checks its index against various online Yellow Pages, giving you a batch of results from your specified area only. But because it incorporates its own relevance rankings, Google sometimes lists a place 10 miles away from you before a place only 2 miles away.

Still, it’s a super-handy search tool, and you can use it to search for general things (Italian restaurants in Boise, ID) or a specific business (Fiesta Market in Sebastopol, CA).

You can run a Google Local search two ways:

From the regular search box. Just type in your search terms plus city and state or Zip code. At the top of your search results, Google includes a few local links, signaled by a compass icon (Figure 2-9, top). If you click through those results, you’ll wind up on a page that looks like the one shown at bottom in Figure 2-9.

Note

If your business is listed incorrectly or is missing altogether, shoot off a note to [email protected] and give them the proper info.

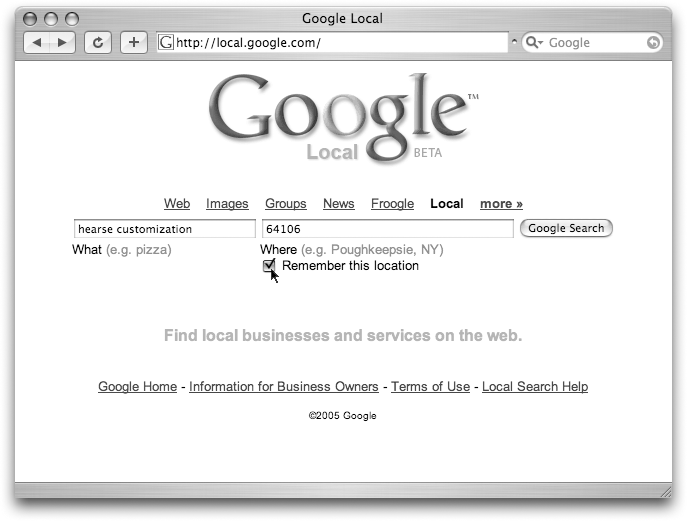

From the Google Local page at http://local.google.com/ . This page (Figure 2-10) is a handy way to use Google Local. When you run a search here, you get a full page of results listings, like the ones shown at bottom in Figure 2-9.

Thanks to Google’s mapping prowess (described in detail in Section 3.3), your Google Local search results now arrive with an interactive map pinpointing the geographical locations of the listed businesses.

Tip

If you want to get all aerial about it, there’s also a link in the upper-right corner of the window to see a satellite photo of the location.

You can scroll through the map to see the surrounding area, either by clicking the arrows or dragging the map. You can also change the map’s scale (use the + and–buttons), or click View Larger Map to open a much larger, more detailed map in its own window.

Google labels each company with a letter, which corresponds to a marker on the map. If you click a marker, a balloon pops up giving you the exact street address and a link to get directions to and from the location. In the upper-right corner of the window, there are even links for searching other distances (one mile, five miles, and so on); click one, and Google gives you new listings that fall within that area.

Tip

The business listings also include a link for directions, but if you click it, you get directions from the center of the town where the business is—not very helpful. Instead, click the marker on the map, and in the balloon that opens, use the direction links to specify where you’re coming from. (To learn more about getting directions from Google, see Section 3.3.2.)

When you click through a company name, you get a new version of the location map with the address marker, along with more information, like which credit cards the business accepts, reference URLs for other Web pages mentioning the company, and links to the sites where Google gleaned all that info. Some business listings, especially those for restaurants, even include reviews that Google has collected from other sites. These reviews are color-coded: a green square is positive, yellow is a neutral opinion, and red means somebody is expressing a less than glowing critique of the establishment.

If you want to fine-tune your search, at the top of the Local results pages, Google gives you search boxes to change the business (What) or location (Where). Just under that, if you turn on the checkbox next to “Remember this location”, Google keeps that location in the Where box every time you open Google Local. To make that behavior stop, just remove the checkmark.

Tip

Looking for a lift? Google RideFinder (http://labs.google.com/ridefinder) helps you hail a taxi, shuttle, or limousine in more than a dozen U.S. cities by displaying vehicle locations (and telephone numbers) in real time on an interactive map. The service works with Internet Explorer for Windows, plus the Firefox, Netscape, and Mozilla browsers for Linux, Mac, and Windows systems but doesn’t yet track that sometimes-elusive automotive creature: the Manhattan yellow cab.

Getting Fancy with Syntax

When you type in a query, you can add words known by the geek term syntax, also called operators, that tell Google something specific about the search you want to conduct. For example, the operator inurl tells Google to look just in URLs for your search terms. Operators are great for honing results, easy as pie, and are the primary uncharted territory of the Google Underusers Club. In some cases, syntax replicates the results you can get via Google’s Advanced Search page, but it’s often more specific, and it almost always saves you some clicking around.

To use any syntax, simply type the operator and a colon before each of your terms, and don’t put spaces before or after the colon. For example, a search using the operator inurl (described in Section 2.6.4) should look like this:

inurl:whammy

or:

inurl:"double whammy"

or:

inurl:double inurl:whammy

Note

URLs never contain any spaces, like the one between “double” and “whammy,” so if your query is inurl:"double whammy”, Google automatically searches for variations like double-whammy; double.whammy; and double,whammy—all of which are perfectly kosher in URLese.

If you type in a space before or after the colon, though, Google can’t read your query.

Searching Titles

As explained in the Advanced Search section earlier in this chapter, titles are different from URLs, and they’re handy to search when you want pages that really focus on your topic. To search titles, use the operator intitle, like this:

intitle:file intitle:sharing

or:

intitle:"file sharing"

The first example finds titles that contain both of your words. The second example finds titles that contain the exact phrase “file sharing.”

A variation of this syntax, allintitle, finds pages that have all your keywords or phrases in the title, in any order. For example:

allintitle:file sharing

finds titles that contain both file and sharing, without your having to put an operator before each word (as in intitle:file intitle:sharing).

Searching Text

The intext operator searches only the body text of Web pages, ignoring links, URLs, and titles. Use this syntax when you want to find a word that may crop up in zillions of URLs or links, like this:

intext:amazon

or:

intext:amazon.com

Its cousin, allintext, works similarly to allintitle, but it, too, has unpleasant issues when mixed with other syntax.

Searching Anchors

Link anchor is HTMLese for the words and pictures on a Web page that serve as links to another page. Mostly, a link anchor is just what you think of as a link (a blue, underlined word or phrase that describes a related, linked page), but a lot of times an anchor turns up as a button or icon or image.

Note

The term “anchor” is confusing because anchors don’t usually refer to both a starting-off point and a destination. But that’s HTML terminology for you.

The inanchor operator searches for text in link anchors. It’s a nifty way to get an idea of which or how many pages link to a person, place, or thing. And sometimes, it can help you find a person’s email address, because most Web pages consider email addresses as links. Use it like this:

inanchor:"Charles Mingus fans" inanchor:"Richard Stallman"

Unsurprisingly, Google also has an allinachor option. (The keywords you specify for allinanchor must all appear in a link anchor in order to show up in your results.)

Searching Within Sites and Domains

Like the Domain feature on the Advanced Search page, the site operator lets you specify a site or domain you want to search. It makes a quick and handy search function for sites that don’t have a search feature.

Unlike the previous operators, the site syntax has two parts. First, you have to attach a site name or domain name to site: And second, you have to include the keywords or phrases you want to search for. Here are a couple of examples:

site:nba.com "larry bird" magic site:gov "agricultural subsidies"

Tip

You don’t have to include http:// or www in the site name. Also, you don’t have to put it in quotes.

You can also use site to exclude a particular Web site from your search. For example, if you want to look for sites about books, but you don’t want to wade through zillions of results from Amazon, this query:

books -site:amazon.com

does the trick. Mostly. It doesn’t block Amazon’s international partners, like Amazon.co.uk, because that’s not the site you specified. To nix all instances of Amazon in a URL, use the inurl operator, described below.

Searching URLs

The inurl operator searches solely URLs for your query words. No body text. No titles. Just URLs. Unlike the site operator, inurl doesn’t require additional query words: inurl:"great pumpkin” is perfectly acceptable. (Remember, a URL can’t contain any spaces, like the one between “great” and “pumpkin,” but if your query includes an exact phrase that has spaces, Google automatically searches for variations that work in URLs, like great.pumpkin and great-pumpkin.)

Inurl is also handy when you want to exclude a site from your search. For example, this search:

books -inurl:amazon

lets you find pages that sell or discuss books, but it blocks any site with Amazon in its URL, which includes the giant retailer and its international partners.

Allinurl is a variation that finds all your keywords, but it doesn’t mix well with some other special syntax.

Who Links to Whom?

Want to find out which sites link to your Web site, or to Friendster.com, or to a particular page on Friendster? The link operator is for you (it does the same thing as the Links feature on the Advanced Search page [Section 2.2]). If you type in link:friendster.com, Google spits out a list of pages linked to Friendster.com.

Caching Up

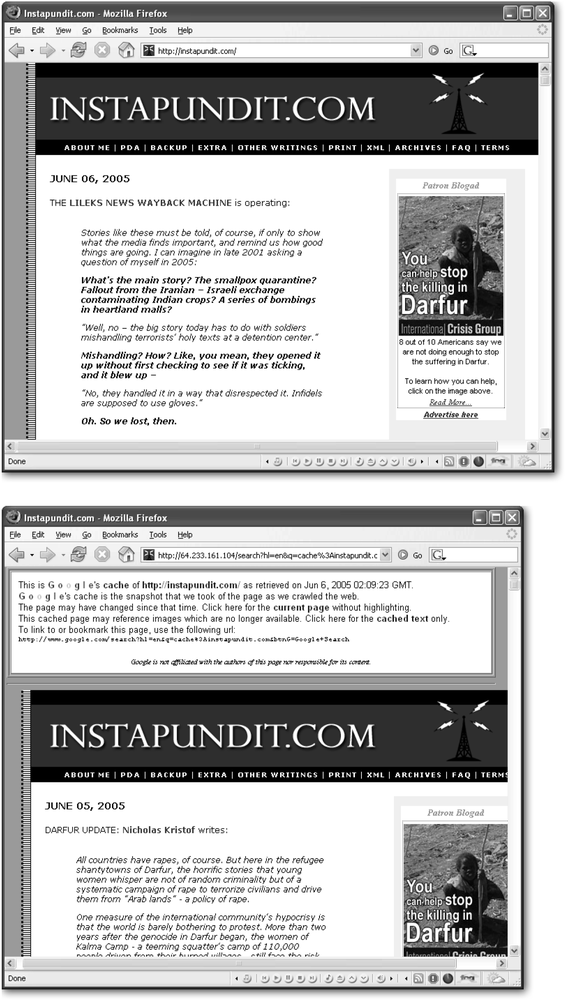

Google keeps a copy of each page as it records it (called a cache), discussed in detail in Section 1.4.1.4. The cache operator lets you view Google’s last cached copy of a page, even if the page has moved from its original URL or changed radically. Thus, this query:

cache:espn.com

gets you the ESPN home page on the last day Google checked it. Figure 2-11 compares a Google cache to a current site.

Tip

If your own site changes regularly, you can use the cache operator to find out the last time Google recorded it.

The cache operator does pretty much the same thing as clicking one of the Cached links on a Google results page, except that using the cache syntax doesn’t highlight your search terms on the cached page. Also, the cache syntax works only with top-level domain names (like giants.com), not with subdirectories (like giants.com/tickets).

Daterange

The daterange operator lets you search for pages that Google indexed during a specific time frame. Like the Date option on the Advanced Search page (Section 2.2), this operator has nothing to do with the date a page was created, but rather when Google recorded it.

So seeing as Google’s Advanced Search page lets you narrow down results, why bother with daterange? Because the Advanced Search lets you limit your results only to the last three months, six months, or year. The daterange operator is a lot more powerful, letting you specify a single day for which you’d like results, or a date before or after which you’d like results (for example, you can search for “terrorism” before and after September 11, 2001).

In fact, daterange can be useful in a few other situations:

Stale results. If you tend to run searches that pull up a lot of old, useless pages, you can use daterange to ensure freshness.

Too much current news. For your doctoral dissertation on weight lifting and masculinity, you want to find some older writings on Arnold Schwarzenegger, but your results are all gummed up with news about the governator. Use daterange to filter out the recent news.

Finding trends. You can use daterange to see how results for a particular query have changed over time. Comparing the number of results for "mad cow" in 1995 to the number in 2005, for example, could make for illuminating study. Plus, the content of certain queries can change over time. What would Google give you if you searched for "Tom Cruise" in 1999 vs. today?

In theory, daterange is easy to use. You just type daterange:startdate-enddate keywords. You have to specify a start date and end date; if you want only one day, use the same date for start and end. In practice, daterange is a power user’s operator because the dates must be in the Julian date form, a continuous count of days since noon on January 1, 4713 BC. In the Julian scheme, July 8, 2002 is 2452463.5.

Though it may seem ridiculous to base an electronic search on a dating system that started thousands of years ago, computers like Julian dates because each is just one number, regardless of leap years, days in a month, and other things that confuse machines. People, on the other hand, tend to take to the Julian calendar like ducks to molasses.

Fortunately, you can easily convert dates from Gregorian (the calendar you’re familiar with) to Julian, and vice versa, at several Web sites. Just run a Google search for "julian date" to get a current list of converters. Even better, you can use the Fagan Finder Google interface at www.faganfinder.com/google.html to specify dates using pop-up menus with Gregorian dates. (For more info about Fagan Finder, see Section 2.2.1.7.)

Note

Google doesn’t officially sanction daterange searches. So if you get funky results, you can’t complain.

You can use daterange in combo with most of Google’s special operators, except the link syntax. Also, the stocks and phonebook operators described in Chapter 1 in Section 1.6.4 and Section 1.6.3, respectively, don’t fly with daterange.

Searching by File Type

The filetype operator searches for file name extensions, like .doc or .pdf. Unlike the similar feature on Google’s Advanced Search page, filetype lets you specify HTML pages (and those encoded as htm, which may give you different results). Geeks can also use filetype to search for page generators—like asp, php, and cgi—little programs that render Web pages suitable for your browser.

You use filetype with keywords or phrases, like this:

"chocolate soymilk ingredients" filetype:ppt

or this:

tofu filetype:xls

to get PowerPoint slides on chocolate soy milk ingredients or Excel spreadsheets on tofu, respectively.

Searching for Related Content

The related operator performs the same search as the “Similar pages” link that appears in a Google result (Section 1.4.1.8). It’s a good way to find pages in a category, rather than with your particular keywords. For example, related:"sesame street" brings up a list of pages on children’s TV shows, while a straight search for "sesame street" yields a lot of sites selling Cookie Monster merchandise.

Synonyms

If your keywords describe a concept, you may want your results to include synonyms for your query. For example, if you’re looking for technical help, it’s useful to automatically include synonyms for “help”—like “support” and “customer service”—without having to type them all in.

The ~ symbol tells Google to look for synonyms. You can find this squiggle near the top of your keyboard, on the key to the left of the number 1 (type it by pressing Shift+'). Use it like this:

~help "Microsoft Word"

to get a list of pages with tips on using the popular word processing program.

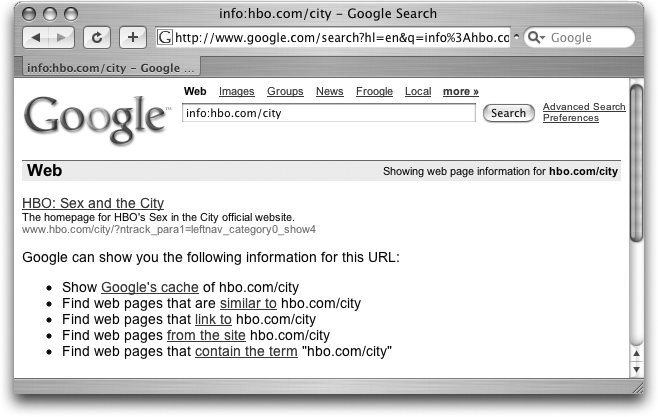

Most of the Kit and Caboodle

The info operator provides you with a tidy summary of the details Google can give you about a URL—including links to that page’s cache, similar pages, linked pages, and pages containing the words in your search. Figure 2-12 shows you what to expect.

Mixing Syntax

As noted above, some syntax operators work only on their own, while some play well with others. For the many you can combine, cleverly splicing them together can narrow your search results in the most satisfying manner. Although you’ll probably have to experiment a lot to find out what works for your searches, the tips below can help, too.

Tip

If you find Google’s syntax confusing to combine at first, stick with the Advanced Search page for now. Then, after performing an advanced search, take a look at the search box on your results pages, where Google has converted your query into syntax. This trick can help you learn which operators do what.

How Not to Mix Syntax

The most important rules to keep in mind are those dictating which syntax not to mix. For starters, a few operators don’t get along with any of the others: allinurl, allintitle, allintext, allinanchor, and link. In addition, there are a few general principles of mixology described below.

Canceling yourself out

Basic safety tip: Don’t mix operators that cancel each other out. For example:

site:bluefly.com –inurl:bluefly

tells Google that you want all your results to come from bluefly.com, but that the results shouldn’t include the word “bluefly” in the URLs. As you’d expect, this search yields exactly zero results.

Doubling up

You can also run into trouble by doubling up a single operator. This query:

"trading spaces" site:com site:edu

might look like you’re asking Google to give you results from either .com or .edu sites, but in fact, you’re telling it that your results should come from sites that are simultaneously part of both domains. Unfortunately, there’s no such thing as a URL like www.google.com.edu.

To get what you want, try this:

"trading spaces" (site:edu OR site:com)

Getting carried away

If you want to run a very narrow search, something like:

intitle:curtains site:ebay.com inurl:funkyfresh

you’re likely to get nothing in return. Instead, start with a broader search, like this:

intitle:curtains site:ebay.com

and then narrow it down by searching within your results (Section 1.2.3).

How to Mix Syntax Correctly

Some syntax combinations work very well. Here’s an example to get you started: intitle and site. If you want to get a sense of the forms available from the United States Department of Agriculture, for example, you could run this search:

intitle:form site:usda.gov

If you want to narrow that down, you can add a keyword, too, like this:

cattle intitle:form site:usda.gov

Tip

You can put keywords at the beginning or the end of your query, but it’s easier to keep track of them if you put them first.

Remember that the site operator lets you specify subdomains (like maps.google.com), so if you want to know what kind of forms the National Agricultural Library has on tap, you could run a search like this:

intitle:form site:nal.usda.gov

Another classic combo is intext along with inurl, described in Section 2.6.4.

Anatomy of a Google URL

As you’ve probably noticed, URLs are often long, complicated, and weird. You certainly don’t have to become an expert in what goes into those addresses. Indeed, millions of people live happy lives never wondering why some URLs are eighteen characters and some are longer than Beowulf.

But after you’ve run a Google search, the URL in your browser bar contains some characters that you can change on the fly to refine a quest without taking a long trip to the Advanced Search page. Plus, once you can read URLese, you can fiddle with URLs to produce results you can’t get any other way.

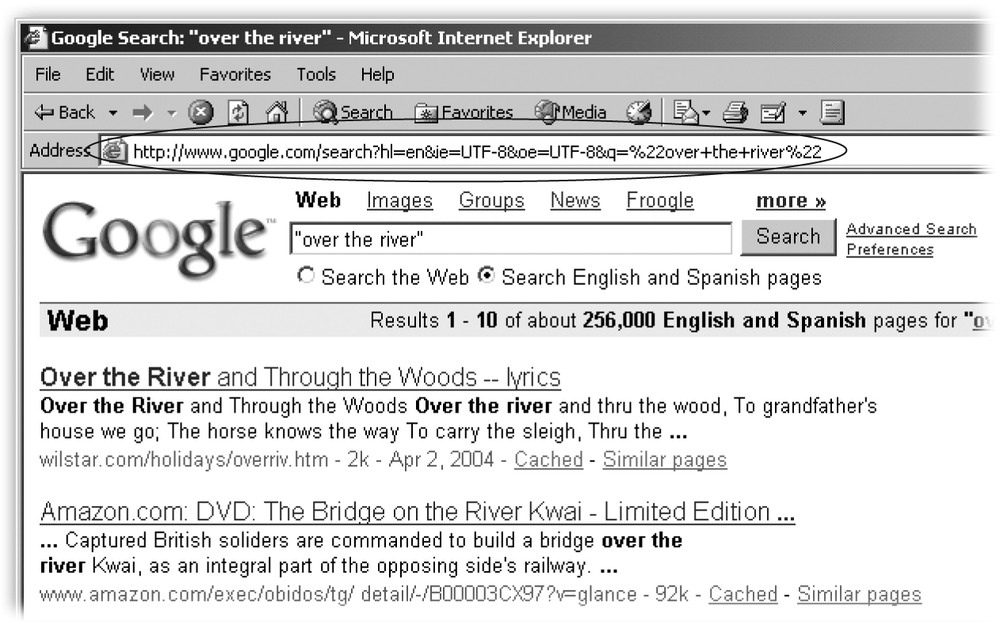

The URL for a Google results page can vary depending on the preferences you’ve set, but mostly, they look similar (see Section 2.1 for more on preferences). Say you run a search for the phrase "over the river“; your results URL should look something like Figure 2-13.

Changing the Number of Results

In the middle of a Google results URL, you can sometimes find num=, which tells you the number of search results Google gives you per page of results. You can temporarily change the number of results to anything from 1 to 100 simply by altering the number in the URL and then pressing Enter. Most of the time, search results are easiest to read when you’ve got 10, 20, or 30 per page (Section 2.1.2). But this trick is a quick way to amp up the number of results on a page for the rare times when you want to review a lot of them at once or compare results 1 and 100 on one page.

Tip

If you don’t see num= in your URL, you can click the end of the URL in your browser’s address bar, add an ampersand (&) and then type in num=whatever. For example, to set the number of results to 50 per page, add &num=50. (Actually, this works even if you can already see the num= setting in your URL, because Google reads URLs from right to left.)

As long as you have the same browser window open, Google keeps your number of results at the new setting. However, Google doesn’t remember the change after you’ve closed the browser; to make the change permanent, see Section 2.1.2.

Changing the Interface Language

In addition to a setting for the number of results, the URL contains a setting for the interface language—that is, the language Google uses on things like buttons and instructions. The setting’s prefix is hl=, followed by a language code. For example, English is denoted thus:

hl=en

Like the number of results, you can alter the URL for a temporary change of interface language. This is most useful when you find yourself in front of a computer that’s set to a language you don’t know—a common problem for exchange students and diplomats. If the language is something other than English but you want English, just change the code to en.

Here’s a list of the codes for the other languages Google knows:

|

Afrikaans. af |

Filipino. tl |

Kyrgyz. ky |

|

Albanian. sq |

Finnish. fi |

Laothian. lo |

|

Amharic. am |

French. fr |

Latin. la |

|

Arabic. ar |

Frisian. fy |

Latvian. lv |

|

Armenian. hy |

Galician. gl |

Lithuanian. lt |

|

Azerbaijani. az |

Georgian. ka |

Macedonian. mk |

|

Basque. eu |

German. de |

Malay. ms |

|

Belarusian. be |

Greek. el |

Malayalam. ml |

|

Bengali. bn |

Guarani. gn |

Maltese. mt |

|

Bihari. bh |

Gujarati. gu |

Marathi. mr |

|

Bork, bork, bork! (Swedish Chef). xx-bork |

Hacker. xx-hacker |

Mongolian. mn |

|

Bosnian. bs |

Hebrew. iw |

Nepali. ne |

|

Breton. br |

Hindi. hi |

Norwegian. no |

|

Bulgarian. bg |

Hungarian. hu |

Norwegian (Nynorsk). nn |

|

Catalan. ca |

Icelandic. is |

Occitan. oc |

|

Chinese (Simplified). zh-CN |

Indonesian. id |

Oriya. or |

|

Chinese (Traditional). zh-TW |

Interlingua. ia |

Persian. fa |

|

Croatian. hr |

Irish. ga |

Pig Latin. xx-piglatin |

|

Czech. cs |

Italian. it |

Polish. pl |

|

Danish. de |

Japanese. ja |

Portuguese (Brazil). pt-BR |

|

Dutch. nl |

Javanese. jw |

Portuguese (Portugal). pt-PT |

|

Elmer Fudd. xx-elmer |

Kannada. kn |

Punjabi. pa |

|

Esperanto. eo |

Klingon. xx-klingon |

Romanian. ro |

|

Estonian. et |

Korean. ko |

Romansh. rm |

|

Faroese. Fo |

Kurdish. ku |

Russian. ru |

|

Scots Gaelic. gd |

Sundanese. su |

Twi. tw |

|

Serbian. sr |

Swahili. sw |

Uighur. ug |

|

Serbo-Croatian. sh |

Swedish. sv |

Ukrainian. uk |

|

Sestho. st |

Tagalog. tl |

Urdu. ur |

|

Sindi. sd |

Tamil. ta |

Uzbek. uz |

|

Sinhalese. si |

Telugu. te |

Vietnamese. vi |

|

Slovak. sk |

Thai. th |

Welsh. cy |

|

Slovenian. sl |

Tigrinya. ti |

Xhosa. Xh |

|

Somali. so |

Turkish. tr |

Yiddish. yi |

|

Spanish. es |

Turkmen. tk |

Zulu. zu |

Two More URL Tricks

By now you’ve probably noticed that you can temporarily change Google’s behavior by placing an ampersand at the end of the results URL and then adding a modifier, which is simply a term or code that alters your results slighly. Here are two more handy modifiers.

Fresh results. By adding &as_qdr=m#, you can alter the maximum age of the results, in months. Just change the # symbol to anything between 1 and 12.

Google’s Advanced Search page lets you say you’d like results that have been updated anytime, within the past three or six months, or year. Yet this trick is an excellent way of narrowing down results to only the freshest pages, and it’s very handy when you’re looking for a page that you’re sure has been changed recently.

Unsafe searching. The SafeSearch filter tells Google to remove potentially offensive links from your results (for more on the filter, see Section 2.1.2). The problem is, sometimes the filter gets carried away and removes things you need (for example, you’re searching for information on sex education, and Google hides some important sites). Or maybe what you want is XXX sites. To make sure the filter is off, add this to the end of your URL: &safe=off. To make sure it’s on, add &safe=on.