Chapter 17

Connecting the Solutions to the Budget Request Line Items

In This Chapter

![]() Orienting yourself to the basic budget components

Orienting yourself to the basic budget components

![]() Understanding matching funds

Understanding matching funds

![]() Calculating your budget with ethics in mind

Calculating your budget with ethics in mind

![]() Showing expenses for multiple years

Showing expenses for multiple years

![]() Opting to use a fiscal sponsor

Opting to use a fiscal sponsor

Many grant applicants create the budget section first, but it’s actually one of the last sections you should tackle. After all, you can’t develop an accurate budget for your grant request until you know all the costs involved in the funded project’s implementation. Where do these cost clues come from? The program design narrative (which I fill you in on in Chapter 15).

This chapter walks you through the budget preparation process for grant applications. It also tells you what the funder’s expectations are when it comes to reading (or scrutinizing) your budget section.

Breaking Down the Basic Budget Sections

Most of the terms associated with the budget section of grant applications and cooperative agreements are everyday terms — no big deal. But when you thoroughly understand each section of the budget, you transform from the “I’m not so sure” grant writer to the “I know how to do this” grant writer who’s ready to tackle the backside of the grant writing mountain. As you start the final climb down, don’t forget your enthusiasm (and don’t forget to breathe)!

Your budget section contains two main parts, allocation and budget detail narrative:

- Allocation: The dollar amount you assign to each line item. The budget summary is the short listing of each line-item expense category and the sum total for the category. At the bottom of it are the total expenses for all the line items listed in the summary. When a funder asks for a budget summary, it wants to see only a graphic table (created by you) or a completed short form (provided by the funder) with your main budget line-item categories and the total amounts for each category. Funders usually don’t want to see narrative detail within a budget summary.

For example, if you’re requesting funding for a staff position only, the two columns in your graphic table are Line Item (left-hand column) and Cost (right-hand column). The first line item is Personnel, and the second line item is Fringe Benefits. These two line items are flush left in the left-hand column. The total project budget, also flush left in the last row of the right-hand column, is the sum of these Personnel and Fringe Benefits columns.

- Budget detail narrative: Funders require a detailed written explanation or narrative of how you plan to spend their monies if they choose to fund your project. So they typically request your budget detail narrative (also referred to as your budget justification or just budget narrative). In the budget detail narrative, you explain and justify the assumptions or calculations you used to arrive at the figures in your budget summary. The budget detail narrative section isn’t the place to spring surprises on the funder. You should have already discussed anything that shows up here in the program design section of the grant application (see Chapter 15 for guidance on crafting an award-winning program design section). Of course, always read the funder’s guidelines and explanations for what should be included in each line-item explanation.

The organization I write about in the later budget detail narrative example (and that I use throughout this section) is a unit of municipal government — the City of Oz — that has existed since the late 1800s. The city needs additional money to create an energy-efficiency initiative that will save on utility expenses at city hall.

Personnel

The personnel portion of the budget summary and budget detail narrative is where you indicate the costs of project staff and fringe benefits that will be paid from the grant funds and from your other resources. If your organization plans to assign existing staff to the grant-funded project but not draw the staff salaries from the grant monies, you need to create an in-kind contribution column to show the funder how you plan to support the costs of the project’s personnel.

Funding for your project’s personnel will either be requested from the funding agency or come as a cash match from your organization (the grant applicant):

- Cash match refers to paid human resources or paid ongoing expenses for your organization allocated to the grant-funded program but not paid with monies from the grant funder. A cash match for personnel means that your organization isn’t planning to request the salary and fringe benefit expenses from the funder; your organization’s operating budget will continue to pay for these expenses.

- In-kind contributions refers to the donation or allocation of equipment, materials, and labor allocated to the grant-funded program but not requested from the funder. (I discuss in-kind contributions in more detail in “In-kind contributions (soft cash match)” later in this chapter.)

- Requested refers to the funds you need to obtain from outside your organization — from the funding agency.

I recommend using FTE (which stands for Full Time Equivalent) throughout your budget forms. FTE is based on a full-time work schedule of 35 to 40 hours per week, depending on how an organization defines full time.For the following budget detail narrative example, I use 40 hours per week for a full-time employee: A 1.0 FTE is 40 hours per week; a 0.75 FTE is 30 hours per week; a 0.5 FTE is 20 hours per week; and a 0.25 FTE is 10 hours per week.

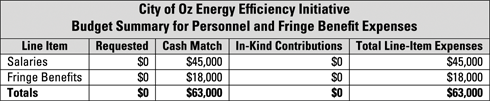

Following is an example of the personnel budget detail narrative from the City of Oz’s grant application:

- Personnel Budget Detail Narrative

- Personnel: One 0.5 FTE facilities manager will be assigned to the grant management duties and project oversight tasks. The operation manager’s full-time salary is $90,000 annually. 0.5 FTE equals $45,000.

- Total Personnel Expenses: $45,000

- Cash Match: $45,000

- In-Kind Contributions: $0

- Requested: $0

- Fringe Benefits Budget Detail Narrative

- Fringe benefits are calculated at 40 percent of total salaries; fringe benefits include medical, dental, vision, short-term disability, worker’s compensation insurance, unemployment insurance, and employer’s FICA match for each salaried position.

- Total Fringe Benefit Expenses: $45,000 × 40 percent equals $18,000

- Cash Match: $0

- In-Kind Contributions: $0

- Requested: $0

Illustration by Ryan Sneed

Figure 17-1: The personnel section of a budget summary.

Travel

If you plan to reimburse project personnel for local travel, traditionally referred to as mileage reimbursement, include this expense in the travel line item of the budget summary and in the budget detail narrative. Be sure to use the current Internal Revenue Service mileage reimbursement rate in your calculations. Also, if you plan to send project personnel to out-of-town or out-of-state training or conferences during the course of the project, you need to ask for nonlocal travel expenses.

Your travel explanation in the budget detail narrative needs to include the number of trips planned and the number of persons for each trip as well as the conference or training program name, location, purpose, and cost. Don’t forget to include the cost of lodging, meals, transportation to the events, and ground travel.

When reviewing the budget-related portions of the grant guidelines, you’re likely to come across the term per diem. In this context, per diem refers to the daily allowance your organization gives employees to spend on meals and incidentals during their travel. Federal grant applications may have per diem limits, such as $105 per day.

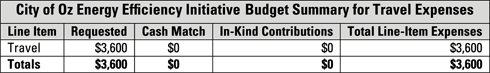

Here’s a portion of the travel budget detail narrative from the City of Oz’s grant application. Notice that the purpose of the travel is clearly explained for the funder. The funds requested are clearly not for “luxurious” travel amenities:

- Travel Budget Detail Narrative

- Travel (Out of State): Grant funding will enable our facilities manager to travel to six metropolitan southwest cities to meet with their facility environment directors and financial staff to determine the most cost-effective fiscal and management process to start this initiative. The following cities will be polled for their processes: Phoenix and Tucson (AZ), Albuquerque and Las Cruces (NM), Salt Lake City (UT), and Palm Springs (CA). Airfare from OZ (commuter airport) to each city is $600 (coach fare) times six flights. Each trip will be a one-day turnaround site visit. No money for meals or ground transportation will be needed.

- Total Travel Expenses: $3,600

- Cash Match: $0

- In-Kind Contributions: $0

- Requested: $3,600

Figure 17-2 shows you one way of graphically presenting the budget information for the City of Oz Project example.

Illustration by Ryan Sneed

Figure 17-2: The travel section of a budget summary.

Equipment

The equipment line item of the budget summary and budget detail narrative is where you ask for grant monies to purchase a major piece of equipment, such as a computer, printer, or other critically needed operational equipment.

You can use government funds to purchase equipment when current equipment either doesn’t exist or is unable to perform the necessary tasks required by the grant. Equipment purchased with government grant funds must be used 100 percent of the time for the grant-funded project.

Here’s an example of the equipment budget detail narrative for the City of Oz Project:

- Equipment Budget Detail Narrative

- Equipment: The City of Oz will purchase heating and cooling leak-detection equipment. This equipment is highly specialized and comes with user training. The facility manager’s staff will use the equipment in teams to check for heating and cooling leaks throughout city hall.

- Total Equipment Expenses: $80,000

- Cash Match: $0

- In-Kind Contributions: $0

- Requested: $80,000

Figure 17-3 shows you how to graphically represent your equipment expenses in an equipment budget summary. The table contains information from the City of Oz Project.

Illustration by Ryan Sneed

Figure 17-3: The equipment section of a budget summary.

Supplies

The materials and supplies needed for the daily implementation of the project go on the supplies line of the budget summary and in the budget detail narrative. Examples include office supplies, program supplies, maintenance supplies, training supplies, operational supplies, and so forth.

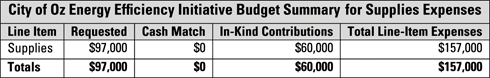

The following is an example of the supplies budget detail narrative for the City of Oz Project:

- Supplies Budget Detail Narrative

- Supplies: Grant funds will purchase weather stripping, sealant, plastic sheeting, and other energy-saving supplies for all city hall windows and doors. City hall has 130 windows and 16 doors. The anticipated cost of these supplies is $97,000. The city has an additional $60,000 worth of these types of supplies already in inventory and will use these items first before initiating a purchase.

- Total Supplies Expenses: $157,000

- Cash Match: $0

- In-Kind Contributions: $60,000

- Requested: $97,000

Figure 17-4 shows a budget summary for the City of Oz Project. It shows the funds needed from the grantor or funding agency, the cash match (which is $0), in-kind contributions (which are $60,000 for this example because the city has supplies on hand), and the total line item for supplies.

Illustration by Ryan Sneed

Figure 17-4: The supplies section of a budget summary.

Contractual

The contractual line of the budget summary and budget detail narrative is where you list the money needed to hire anyone for the project who isn’t a member of the staff (staff expenses are listed under the personnel section of the budget that I cover earlier in this chapter). For example, you may plan to hire a construction contractor to build or renovate a room or building; an evaluation specialist to work on that portion of the application; or a trainer to work with your staff, clients, or board members.

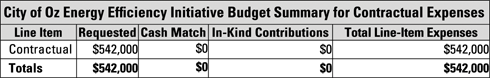

Here’s an example of the contractual budget detail narrative for the City of Oz Project:

- Contractual Budget Detail Narrative

- Contractual: The City of Oz will create a “request for bid” document to identify a solar energy vendor. The city council has requested that 100% of city hall be heated and cooled with solar panels. The city has collected several estimates for this work. The most cost-effective bid specifications are $542,000 for 50 panels. This price includes installation and a 10-year warranty with guaranteed replacement at no additional charge to the city.

- Total Contractual Expenses: $542,000

- Cash Match: $0

- In-Kind Contributions: $0

- Requested: $542,000

To see a contractual budget summary for the City of Oz Project, check out Figure 17-5.

Illustration by Ryan Sneed

Figure 17-5: The contractual line of a budget summary.

Construction

When you write a grant that’s exclusively seeking funds for construction (also known as building funds), you don’t need to bother with a budget summary and a budget detail narrative. Just insert a copy of the bid, which is the written document submitted to you by the construction company that lists all the costs involved in the project. Shortcuts are nice!

Other

You may need to include this section in your budget summary and in the budget detail narrative if you have items that don’t fit into any of the other categories. List items by major type and show, in the budget detail narrative, how you arrived at the total sum requested. Typical expenses that fall under the Other category are as follows:

- Internet

- Janitorial services

- Rent

- Reproduction (printing)

- Security services

- Stipends or honorariums for speakers or special project participants

- Telephone

- Utilities

- Vehicles

- Volunteers (check out the nearby sidebar for help calculating the value of volunteer hours)

For the City of Oz Project, there are no additional expenses for the Other line item.

Distinguishing between direct and indirect costs

Direct costs are expenses for most of the services and products mentioned in the previous sections — everything from the budget categories you’ve already listed.

Indirect costs — often called overhead — cover services and products essential to your overall organization that are consumed in some small degree by the project. Some indirect costs include things such as the telephone bill, rent payments, maintenance costs, and insurance premiums.

Indirect costs are usually calculated as a percentage of total direct costs. They can range from as little as 5 percent for a small nonprofit organization to as much as 66 percent for a major university. Your agency may already have an approved indirect cost rate from a state or federal agency, in which case the information is probably on file in the business manager’s office. If your agency’s business manager doesn’t have that information, contact the U.S. Office of Management and Budget or your state’s fiscal agency. (Note that to recover indirect costs related to federal awards, you likely have to negotiate an indirect cost rate, or ICR, with the federal agency providing the majority of the funding. When this ICR is approved, it’s referred to as a negotiated indirect cost rate agreement or NICRA.)

I’ve actually written federal grant applications with 50 percent indirect cost rates built in. This scenario means that if the application is funded and the direct costs total $500,000, another $250,000 gets tacked on for indirect costs. (Those are your taxes at work!) Additionally, many government grants limit or cap the indirect rate that can be charged for the project. Make sure to read the budget guidance carefully so that you adhere to any restrictions.

The following is an example of an indirect costs narrative. Note that the $86,712 requested for indirect costs covers project-related expenses for existing window and door energy-efficiency-related maintenance and repairs, utilities, office space for the facilities staff, and custodial costs:

The City of Oz has been approved for an indirect cost rate of 12 percent by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget. This approval was granted in 2010 when we applied for and received our first U.S. Department of Energy grant to study the use of a wind-driven energy system. Indirect charges are calculated for the total government funds requested or $722,600 – $542,000 [contractual expenses] = $180,600 × 12 percent, or $21,672.

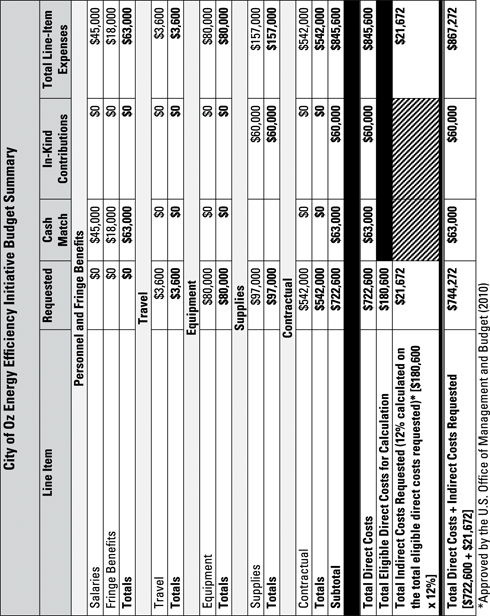

Entire budget summary

Total Direct Costs (Federal Request): $722,600

Total Eligible Indirect Costs: $21,672

Total Federal Request: $744,272

Cash Match: $63,000

In-Kind Contributions: $60,000

Total Project Budget: $867,272

Figure 17-6 shows you how the entire budget summary for the City of Oz Project example looks when it’s pulled together.

Illustration by Ryan Sneed

Figure 17-6: The City of Oz Project’s entire budget summary.

Uncovering Matching Funds

If you’re applying for consideration with a funder that requires matching funds, then this is the section for you. Push your fears aside and rev your engine, because finding matching funds is about to become a lot easier. First of all, read the grant application instructions regarding matching funds. Ask yourself how this funder defines matching funds. Can the match be an in-kind contribution, also referred to as soft cash, or are you required to identify actual cash (called a hard match) for the match?

In my travels across the country, I’m amazed at the feedback I get about how difficult it is for grant applicants to come up with required matching amounts in order to qualify for some state and federal grants. I’ve put together the following information to assist you in finding those much-sought-after matching funds.

- The first column is for the specific line-item categories.

- The second column is for the amount of grant or contract funds requested.

- The third column is for the cash match.

- The fourth column is for the in-kind contributions. If you have no in-kind funds, mark the amount as $0.

- The fifth column is for the total of columns one through four.

This setup is what I use in the budget table figures throughout the chapter.

In-kind contributions (soft cash match)

The in-kind part of the budget summary and budget detail narrative is where you list the value of human and material resources your organization will make available to the grant-funded project (meaning you aren’t asking the funder for all the resources needed to implement the project).

When a grant application requires matching funds, every dollar requested from the funding source must be matched with a specified percent of your own monies. The funder’s guidelines tell you whether the match is 10, 20, 50, or 100 percent or higher. Some funders require a 3:1 or 4:1 match, meaning if you request $100,000, you must come up with matching funds in the amounts of $300,000 and $400,000, respectively.

- Construction: Eligible construction is any aspect of infrastructure work that will be donated by trade professionals or volunteers.

- Contractual: Eligible sources are contracted consultants who will lend their expertise and time to the project after it’s funded but whose expenses may not be requested from the grant-funder.

- Equipment: Eligible equipment must be existing and you must document fair market value for each item.

- Indirect charges: Eligible indirect charges can be a line-item request in the grant budget; however, if you’re struggling to identify matching funds, use indirect charges as a matching contribution to be absorbed by your project.

Indirect charges range from 5 percent to 66 percent of the budget subtotal and are allowable in federal grant applications only. In some rare instances, foundations permit indirect charges as well, but they usually set a percentage cap, such as 10 percent of the total budget. Make sure you know and follow each specific funder’s directions for how to include and calculate indirect charges.

- Miscellaneous: Other eligible sources include utilities and telephone expenses related to implementing the project but that aren’t allowable line items in the funding request; printing, copying, postage, and evaluation expenses not included in contractual or supplies; and any other costs your project will incur that haven’t been requested from the funder.

- Supplies: Eligible supplies must be on hand from existing inventory.

- Travel expenses: Eligible travel must be grant-related for key or ancillary personnel, and money for the expenses can’t be requested from the grant funder.

Cash match (money on hand allocated for cash matching funds)

Inventory your cash on hand and work with your finance person or business manager to determine how much of the cash on hand can be used as cash match for the project, if funded. Remember that your cash match must be connected to grant-funded activities and related expenses:

- Equipment: Equipment purchased by your organization with its own money that’s connected to the grant-funded project.

- Fringe benefits: Eligible fringe benefits for administrative, clerical, contracted, and facilities personnel are prorated based on the actual amount of time these staff members will contribute to funder-supported activities. Your organization pays these benefits.

- Personnel: Personnel who will provide direct or indirect services for the grant-funded activities but who won’t be charged to the project’s budget expenditures as a line-item request to the funder. So, on a prorated basis, administrative, clerical, contracted, and facilities personnel (including custodial staff) can all be used as cash match line items. Salary for these personal must be paid by your organization in order to count as cash match.

- Supplies: Supplies purchased by your organization with its own money and connected to the grant-funded project.

- Travel: Travel that your organization will pay for from its own funds connected to the grant-funded project.

- A specialized allocation (when your chief financial officer transfers cash from the general operating funds account into a specially allocated account to be used for cash matching funds).

- Other state or federal grant funds. You can’t use existing federal grant funds to match new/incoming federal grant funds; check with the funding agency for specific restrictions on matching funds.

- Private sector grants for portions of the project.

- Your general operating funds (unrestricted monies to pay the day-to-day operating expenses of your organization).

Generating the Numbers Ethically

Completing a project budget can be an individual effort or a team effort. Either way you go about it, however, developing thorough and accurate project budgets to present to funders involves more than just putting numbers down in a line and adding them together. Many factors affect how much you ask for in grant funding.

Gathering accurate cost figures

Not sure what kind of budget numbers to put down? Can’t figure out how much you’ll have to pay a program director? Unclear how much you’ll have to spend on a copy machine? I have an easy solution: Use your telephone. Call the United Way in your area, for example, to find out its salary ranges for program directors, program coordinators, clerical support, accounting clerks, and other staff positions. Call vendors for specification sheets on equipment. It’s amazing how quickly you can find answers by asking people in the know!

The Internet has a wealth of information on nonprofit organizations, including salary surveys. Run a quick Internet search, using your favorite search engine, for nonprofit salary surveys.

Including all possible program income

If you anticipate having any program income at all, you must list a projected amount at the end of your budget summary table and subtract it from the total project costs; doing so means you need less money in grant funds. Examples of possible program income include the following:

- Interest: You may earn interest on endowment funds you’re allowed to use annually to assist with program costs.

- Membership or program fees: A public library has late fees that add to its overall program income, for example. Likewise, a program may charge participants a small fee to enroll in program classes or services.

- Special events revenue: You may be planning to hold a fundraising auction or raffle to collect additional monies for field trips, equipment, or other items or activities in the project’s design.

- Ticket sales for planned events: You may work within a performing arts organization that puts on three plays at the local community theater, and patrons purchase tickets to see your troupe perform.

- Tuition: You may receive payment or reimbursement from a state or local agency for aiding a specific population. Your grant request may be for monies to develop additional programs, but you must account for the monies you already take in.

Managing expenditures to the penny

Asking for too much isn’t looked upon favorably by any funding source. In fact, giving leftover money back at the end of the grant period may mean you can’t go back to that funder, ever. No funder wants money back. Why? The funder has already worked the grant award or allocation into its annual giving budgets. Returned money is a hassle, from accounting to reallocation, if the funder has a specific amount of grant funds it awards annually.

To top it off, giving grant award money back may send one or more of these signals to funders:

- Your organization (the grant applicant) didn’t submit an accurate budget request — you overshot some of the line items and now you have more money than you know what to do with!

- You aren’t creative enough to find a way to use the leftover monies in your project to better serve the target population.

- You failed to carry out all the proposed activities and had leftover monies.

Meet with your board of directors or project advisory council to brainstorm how you can (legally) spend the monies on project-related needs.

Projecting Multiyear Costs

When you’re planning to construct a building or purchase specific items of equipment, engineers or vendors can usually give you bids that are very close to the actual cost of the construction or equipment you’ll need. However, when you’re seeking funding for personnel or line items with prices that fluctuate, take care to account for inflation when preparing your budget.

Here’s how to create an award-winning multiyear budget summary table:

- Column 1: Type your line-item categories (listed at the beginning of this chapter).

- Column 2: Type your Year 1 in-kind contributions by category.

- Column 3: Type your Year 1 cash contributions by category.

- Column 4: Type your Year 1 amounts requested from the funder by category.

- Column 5: Type your Year 2 in-kind contributions by category.

- Column 6: Type your Year 2 cash contributions by category.

- Column 7: Type your Year 2 amounts requested from the funder by category.

Continue this sequence for all remaining years in your multiyear budget support request. Only run your total at the bottom of each column, vertically. Don’t run horizontal totals (at the end of rows); it’s too confusing for the funder to nail down the actual costs and requests for any specific year. Use an Internet search engine to find examples of multiple year budgets.

Building Credibility When You’re a New Nonprofit

If your organization is a new nonprofit, you can increase your chances of winning a grant award by applying through a fiscal sponsor. A fiscal sponsor is usually a veteran agency with a long and successful track record in winning and managing grants; of course, the sponsor must have 501(c)(3) nonprofit status awarded by the IRS.

The role of a fiscal sponsor is to act as an umbrella organization for newer nonprofit organizations that have little or no experience in winning and managing grant awards. Your new organization is the grant applicant, and the established agency is the fiscal sponsor. It acts as the fiduciary (financial) agent for your grant monies. In other words, your fiscal sponsor is responsible for depositing the monies in a separate account and for creating procedures for your organization to access the grant monies.

Why would you use a fiscal sponsor instead of applying directly for grant funds yourself? Because some foundations and corporate givers don’t award grant monies to nonprofit organizations that haven’t completed the IRS advanced ruling period — typically a 36-month time frame during which the IRS is monitoring your nonprofit-related activities and finances to make sure you’re fulfilling the mission, purpose, and activities stated on your nonprofit status application (Form 1023). No funder wants to award substantial grant monies (more than $10,000) to a nonprofit in the advanced ruling period. Note: Government agencies don’t have advanced ruling period–related requirements.

When selecting a fiscal sponsor, do the following:

- Find a well-established nonprofit organization with a successful track record in financial management.

- Ask your local banker to make a recommendation for a suitable fiscal sponsor.

- Look for community-based foundations set up to act as umbrella management structures for new and struggling nonprofit organizations.

- Choose a sponsor you’re on good terms with and one you have open lines of communication with. Otherwise, your grant monies may be slow in trickling down.

When it comes to your relationship with your fiscal sponsor, keep the following points in mind:

- The fiscal sponsor is responsible if your organization mismanages the money.

- The fiscal sponsor is responsible if the fiscal sponsor mismanages the money.

- If an audit for financial expenditures is in order, the funding source can audit the fiscal sponsor, and the fiscal sponsor can audit your organization.

Sometimes a fiscal sponsor wants you to include expenses for accounting services or grant management in the Other section of your budget summary and in the budget detail narrative. This practice is acceptable to funding sources.

The following is an example introduction of an organization that plans to use a fiscal sponsor:

The Ready for the World Future Forward Initiative (RWFFI) will use the Entertainment Industry Foundation as its fiscal sponsor. Although our organization is a recognized nonprofit organization in the state of Wonderland and approved by the IRS for nonprofit tax-exempt status, the RWFFI has never managed a grant in excess of $1,000,000. Our board’s executive committee has met with the financial manager at the Entertainment Industry Foundation and has obtained a written fiscal agent agreement. For this request, the grant applicant is RWFFI; however, the fiscal agent will be the Entertainment Industry Foundation. We have attached a profile of the foundation as well as its signed fiscal agent agreement. IRS letters of nonprofit determination for both organizations are attached.

Your budget is connected directly to your project’s measurable objectives and implementation activities. And in order to achieve the measurable objectives, a series of implementation activities or process objectives must occur. The line items in your budget are the costs of carrying out the activities that lead to the achievement of your objectives; these costs can include salaries, fringe benefits, travel, equipment, and supplies. Translation: Dollars are linked to activities and their resulting costs.

Your budget is connected directly to your project’s measurable objectives and implementation activities. And in order to achieve the measurable objectives, a series of implementation activities or process objectives must occur. The line items in your budget are the costs of carrying out the activities that lead to the achievement of your objectives; these costs can include salaries, fringe benefits, travel, equipment, and supplies. Translation: Dollars are linked to activities and their resulting costs. Don’t forget to keep a copy of your proposal documents for your own files! For anytime access, I moved all my grant-related backup files from my computer’s hard drive to cloud-based storage.

Don’t forget to keep a copy of your proposal documents for your own files! For anytime access, I moved all my grant-related backup files from my computer’s hard drive to cloud-based storage. I want to emphasize that you shouldn’t include cash-match or in-kind dollar amounts in the Requested line item of the budget summary or in the Requested line-item detail narrative. Your cash-match and in-kind items should appear in a separate column. Figure

I want to emphasize that you shouldn’t include cash-match or in-kind dollar amounts in the Requested line item of the budget summary or in the Requested line-item detail narrative. Your cash-match and in-kind items should appear in a separate column. Figure  If you apply for a government grant and your organization has an indirect cost rate of 20 percent, you can choose not to ask for the entire 20 percent from the funding agency. Instead, because you want to look good and capable of managing a grant, you can ask for 10 percent from the funding agency and make up the other 10 percent as an in-kind contribution. (See the later section “

If you apply for a government grant and your organization has an indirect cost rate of 20 percent, you can choose not to ask for the entire 20 percent from the funding agency. Instead, because you want to look good and capable of managing a grant, you can ask for 10 percent from the funding agency and make up the other 10 percent as an in-kind contribution. (See the later section “ Visit

Visit