KNOWLEDGE

In Halls

In many of its guises, graphic design has only intermittently been the subject of exhibits or on display in the permanent collections of museums around the world, but as the profession’s fame grows and the value of its historic artifacts comes to light, more and more contemporary art museums are displaying posters, logos, packages, and brochures with the same reverence and care afforded to other artists. Through retrospectives of individual designers or themed exhibitions, museums offer the pleasure of seeing original pieces of work more typically experienced at small sizes in books and catalogs. Equally encouraging are the growing acquisitions of design work these museums make, to be preserved and handled with white gloves.

Preserving graphic design is a fraction of the concern at larger museums, so the importance of smaller archives and study centers strongly focused on graphic design is paramount to maintaining physical samples of graphic design, which is fleeting by nature. Housed within universities, design schools, and museums, such archives offer researchers and curious designers the rare opportunity to leaf through 40-year-old annual reports and centuries-old type specimens, or to stand next to 6-foot-tall posters.

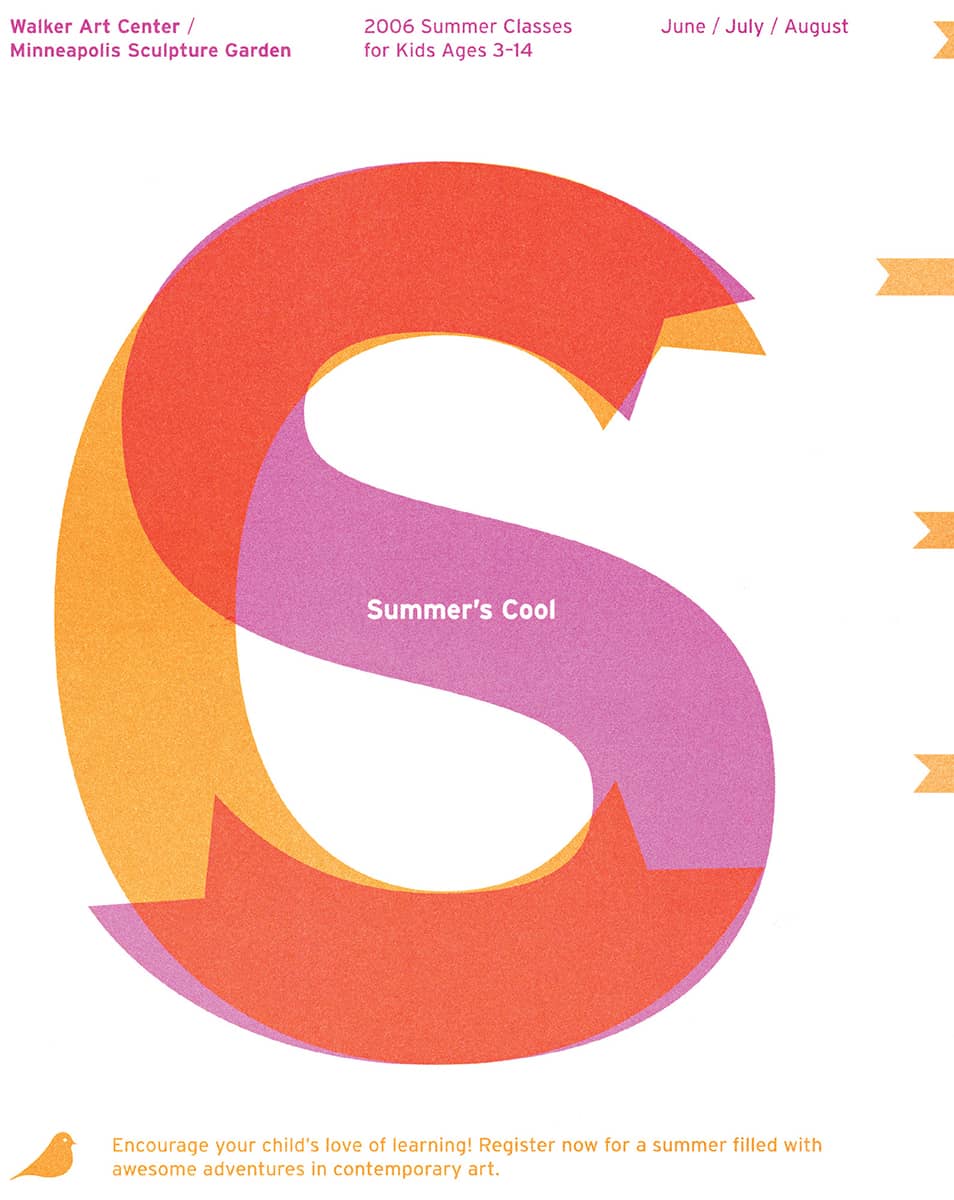

Detail of 2006 SUMMER CLASSES BROCHURE FOR THE WALKER ART CENTER, MINNEAPOLIS SCULPTURE GARDEN / Walker Art Center: design, Scott Ponik / USA, 2006

Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum

As the only museum in the United States completely devoted to historic and contemporary design, the Cooper-Hewitt, founded in 1897, is one of the industry’s most ardent champions, presenting the importance of design to a wide public. Its ambitious National Design Triennial series, started in 2000, is paramount in weaving the different manifestations of design. The annual National Design Awards, launched in 1997 to celebrate the best practitioners in a variety of creative fields, have attracted a healthy dose of media attention. With Ellen Lupton › 240 as curator of contemporary design since 1992, the museum has produced tightly focused exhibitions on graphic design, like The Avant-Garde Letterhead (1996), Mixing Messages: Graphic Design in Contemporary Culture (1996–1997), and Graphic Design in the Mechanical Age (1999), among others. A visit just to experience contemporary design in the historic Andrew Carnegie Mansion in New York is well worth the price of admission.

Walker Art Center

Minneapolis’ Walker Art Center, founded in 1927, offers a rich array of experiences in the form of exhibitions, lectures, performances, and workshops, and has long been associated with graphic design; Design Quarterly, published from 1946 to 1993, regularly featured the work of graphic designers; Insights, an ongoing lecture series in collaboration with the Minnesota chapter of the AIGA › 244, has been running since 1986; a landmark exhibit curated by Mildred Friedman in 1989, Graphic Design in America: A Visual Language History, further cemented its consideration for the profession; and, perhaps most notably, its in-house design group has produced all the catalogs, exhibit graphics, collateral, and identity components of the organization under the guidance of design directors Mildred Friedman (1979–1990), Laurie Haycock Makela (1991–1996), Matt Eller (1996–1998), and Andrew Blauvelt (1998–present), garnering acclaim and building goodwill with the industry.

New York Museum of Modern Art

The New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), founded in 1929, is known for its impressive permanent art collection, certainly with good reason, and while product design is a more common sight, graphic design has briefly seeped onto its walls. Most recently, it has been entwined in the elaborate and comprehensive SAFE: Design Takes on Risk (2005–2006) and Design and the Elastic Mind (2008) exhibitions curated by Paola Antonelli, the museum’s senior curator in the department of architecture and design. Past exhibitions include The Graphic Designs of Herbert Matter (1991), Typography and the Poster (1995), Stenberg Brothers: Constructing a Revolution in Soviet Design (1997), The Russian Avant-Garde Book, 1910–1934 (2002), and Fifty Years of Helvetica (2008). MoMA has also acquired the work of Irma Boom › 193, Massimo Vignelli › 160, and Willi Kunz › 257, as well as a set of lead Helvetica › 373 Bold 36-point type from 1956.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

With a versatile mix of media making up the exhibits at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), it is exalting that graphic design has continually been included in the rotation. Drawing from its permanent collection of architecture and design, SFMOMA regularly features the work of West Coast designers like Rebeca Méndez, AdamsMorioka, Jennifer Morla, Jennifer Sterling, Martin Venezky, and Lorraine Wild. In 1999 it presented Tiborcity: Design and Undesign by Tibor Kalman, 1979–1999; it has displayed editorial work from the pages of Emigre › 100 and Wired magazines, and Belles Lettres: The Art of Typography, was shown in 2004.

Victoria and Albert Museum

Somewhere within the more than 500,000 square feet of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), founded in 1852, and amid its voluminous collections and exhibitions of paintings, ceramics, sculpture, textiles, and furniture, glimpses of graphic design shine brightly. Aside from its iconic logo, designed by Alan Fletcher in 1988, V&A has wooed the industry with exhibitions like Brand.New (2000–2001), Paper Movies: Graphic Design and Photography at Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue , 1934–1963 (2007), and the momentous Modernism: Designing a New World, 1914–1939 (2006) and China Design Now (2008). To coincide with the Beijing Summer Olympic Games in 2008, the V&A organized A Century of Olympic Posters, which will go on tour until the 2012 games in London.

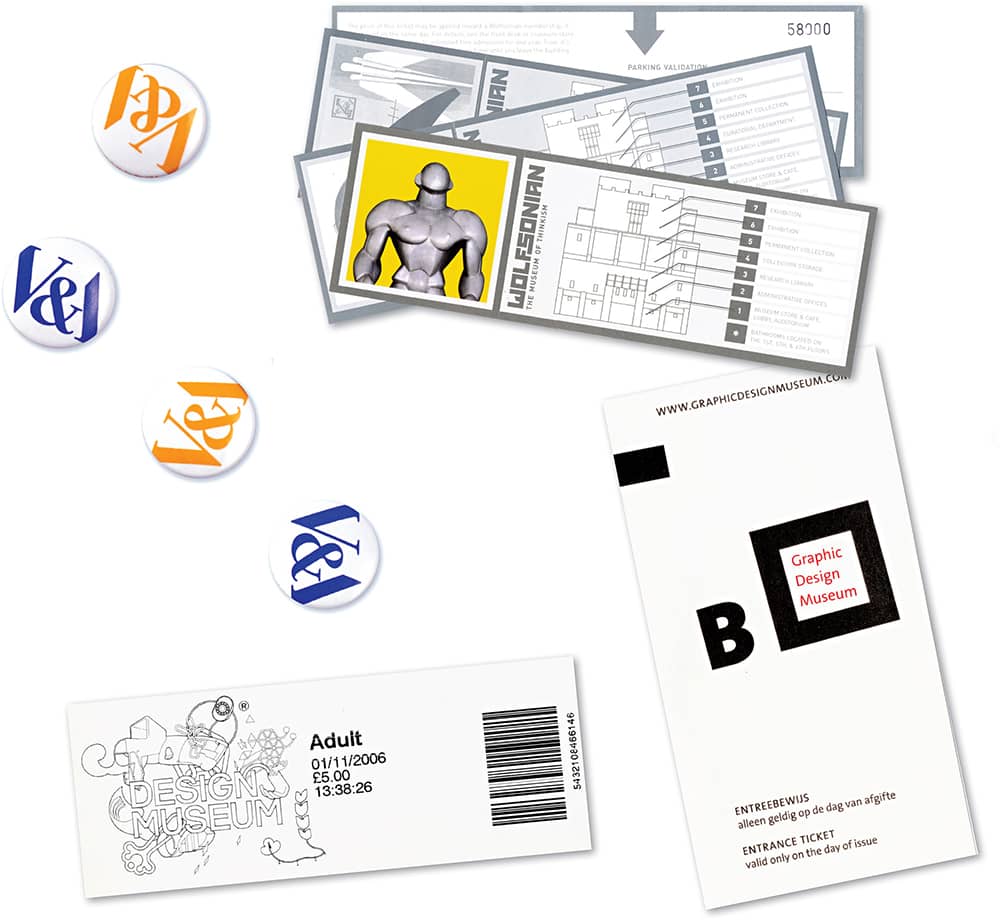

Design Museum

Before the Design Museum opened its halls in a renovated 1940s banana warehouse in 1989, it had a previous iteration as the Boilerhouse, a gallery located in the basement of the Victoria and Albert Museum, established by Terence Conran and directed by Stephen Bayley. Both incarnations aimed to bring attention to the practice of design. In its brief history, the museum has already experienced its share of controversy as resignations and inside spats have become public—and not worth relating here—oddly distracting from the content it offers. For graphic designers, the tenure of director Alice Rawsthorn › 241 (2001–2006) may be the most fruitful, as she fostered exhibitions on Peter Saville › 180, Saul Bass › 158, and Alan Fletcher; recent exhibitions on Robert Brownjohn › 155, Jonathan Barnbrook, and Helvetica › 373 have fared substantially well. Since 2003, the museum has bestowed a £25,000 prize to a Designer of the Year, an initiative that regularly ends in controversy.

Wolfsonian–Florida International University

Originally founded in 1986 to exhibit and document the decorative and propaganda arts collection of Mitchell Wolfson Jr., the Wolfsonian became a part of Florida International University (FIU) in 1997 when Wolfson donated the collection and its historic Miami Beach building, a now-renovated seven-story, 56,000-square-foot museum. The Wolfsonian-FIU is home to an enviable collection of twentieth-century political propaganda, including prints, posters, drawings, and books from Germany, Italy, and the United States, as well was material from the United Kingdom, Spain, Russia, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary. Other collections that may cause designers to salivate are holdings of posters, catalogs, and other ephemera from the transportation and travel industry—ocean liners, airplanes, zeppelins, and trains—and from the World Fairs and Expositions. In 2008, the museum presented Thoughts on Democracy, an exhibition that showcased the work of 60 designers who reinterpreted Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms posters.

Graphic Design Museum

Iconic urban design hubs like New York, San Francisco, London, and The Hague lack one thing that Breda, a small city of approximately 200,000 in the south of the Netherlands, has: a museum devoted solely to graphic design. Opened in 2008, the Graphic Design Museum, Beyerd Breda, is the first of its kind, as much for its content and focus as for its approach to providing exhibitions and resources targeted toward adults, kids, and an in-between category simply labeled “young.” One of the main attractions upon its inauguration was the retrospective show 100 Years of Graphic Design in The Netherlands. Fingers crossed, this museum will have many imitators.

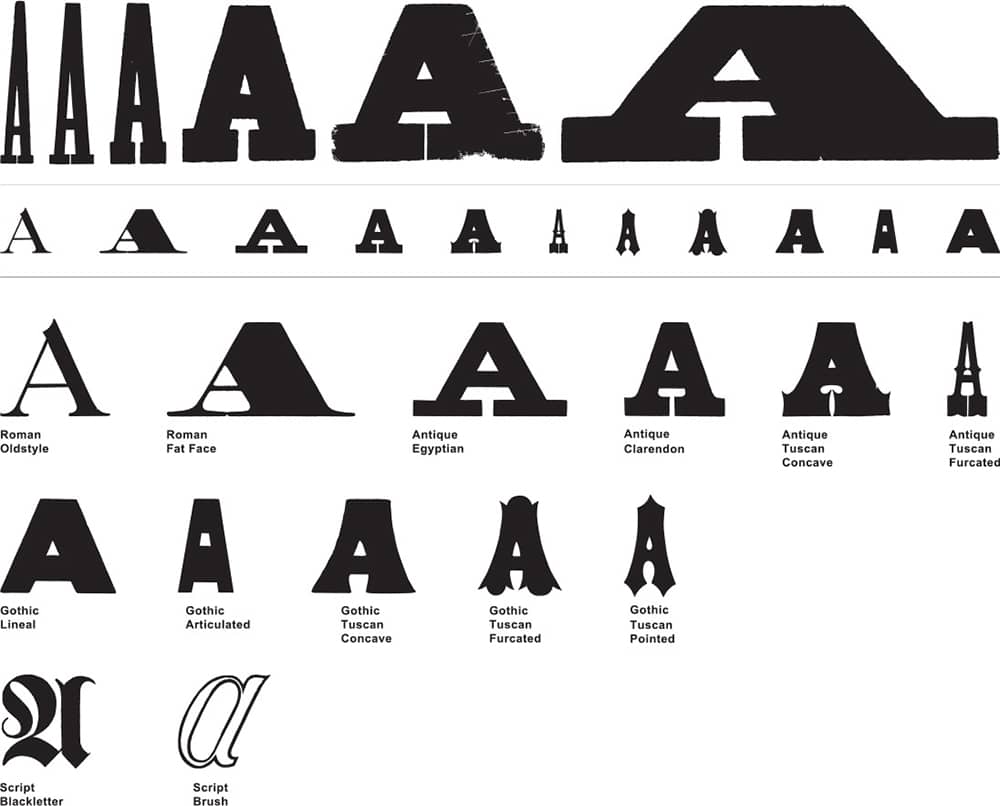

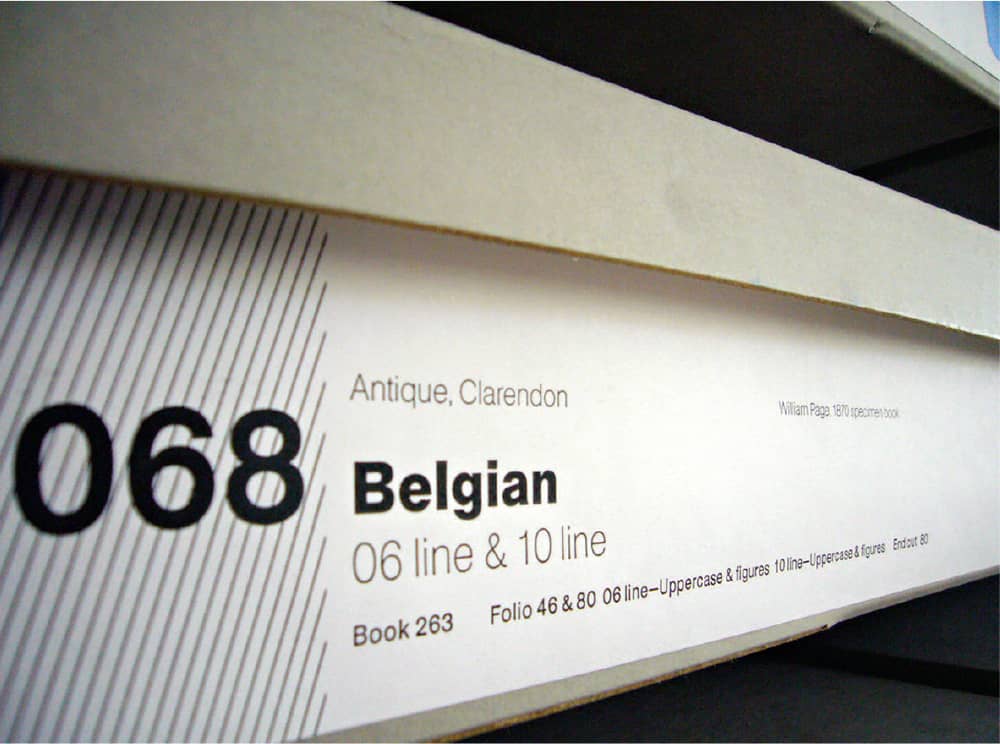

St Bride Library

Opened in 1895, the St Bride Library in London specializes in printing and its supporting specialties of typography, calligraphy, photography, book binding, and printmaking, among dozens of others. With approximately 50,000 books, 3,500 periodicals, catalogs and directories, a collection of metal and wood type from the seventeenth to the twentieth century, and special collections holding the work of W.A. Dwiggins › 141, Eric Gill, and Beatrice Warde, the St Bride Library is, literally, a treasure trove.

AIGA Design Archives

If browsing lauded graphic design through a web-based Flash interface › 116 does not satisfy a designer’s curiosity, a visit to the AIGA Design Archives, housed since 2006 in the Daniel Libeskind-designed Denver Art Museum, probably will. The archive holds the winning selections from the AIGA’s national design competitions since 1980. In 2007, Darrin Alfred was assigned as the AIGA Assistant Curator for Graphic Design, overlooking the collection as well as managing additional acquisitions like the 875 psychedelic rock posters and 20 works by Art Chantry › 184 it acquired in 2008.

Rob Roy Kelly American Wood Type Collection

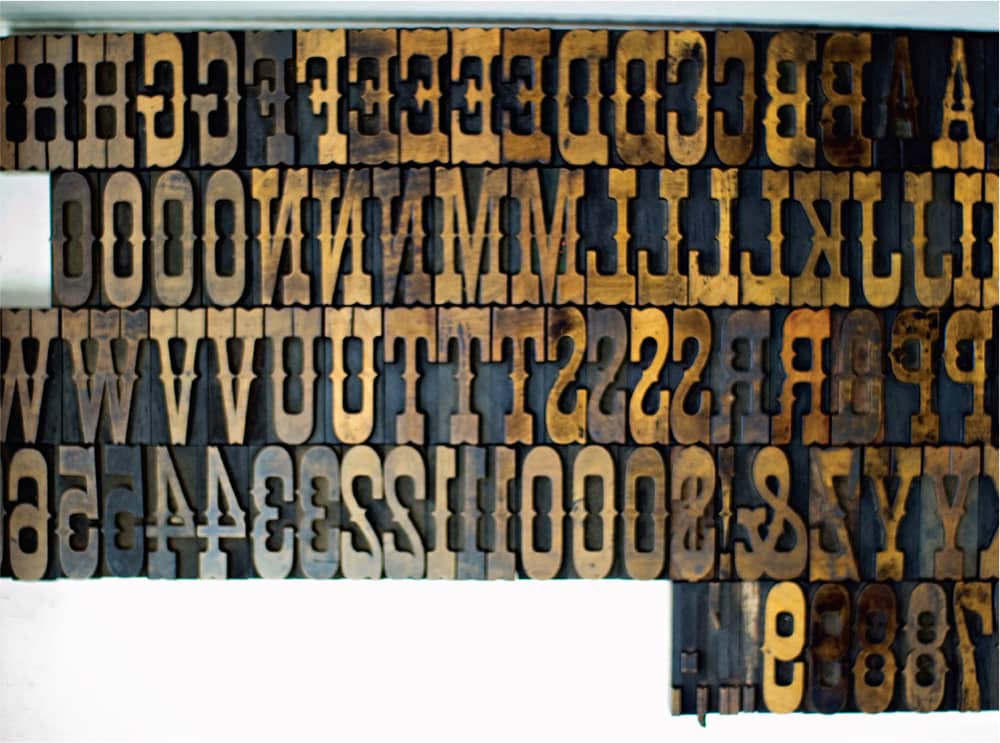

For his seminal publication, American Wood Types 1828–1900, Volume One › 72, Rob Roy Kelly amassed a large collection of wood type that, as it became hard to manage, he sold to MoMA’s › 121 head librarian, Dr. Bernard Karpel, in the 1960s. In turn, Karpel sold it to the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin (UT) within six months. The collection languished there until 1991, when the Center was about to toss it as it reorganized its space but instead contacted the university’s art department to see if anyone would be interested, and professor Gloria Lee adopted it. In 2004, as part of his tenure research at UT, David Shields unofficially took over the collection and started to work with students to unpack the 40 boxes and explore their contents. By printing and digitizing the entire collection, they arrived at 135 type families (close to 170 unique typefaces), many of which had not been published in Kelly’s book—and, most promising, Shields encourages visitors to come in and use the type, as it was meant to be.

Herb Lubalin Study Center

Established within the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art › 131 in 1985—curated by Ellen Lupton › 240 until 1992, and now headed by Mike Essl and Emily Roz—the Herb Lubalin Study Center of Design and Typography contains a vast collection of work from the twentieth century. Its most significant collection is a comprehensive archive of the logo, editorial, and packaging work, along with hordes of sketches, of Herb Lubalin › 167, a Cooper Union alumnus. Smaller collections of Lou Dorfsman › 173, Herbert Bayer, Bradbury Thompson, Alvin Lustig › 144, and Alexey Brodovitch › 143, as well periodicals and posters, complement the archives.

Type Directors Club Library

The library of New York’s Type Directors Club (TDC) › 247 is replete with type specimens, foundry catalogs, broadsides, and calligraphic works. A rare item in the Type Directors Club collection is a 15-minute videotape culled from reels of the great American type designer Frederic W. Goudy.

Analysis of the American Wood Type Collection showing the range of the styles and the different widths found

Graphic Design Archives at Rochester Institute of Technology

Established by R. Roger Remington under the administrative care of the broader Cary Graphic Arts Collection at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT), the Graphic Design Archives focus on the work of American graphic designers working from the 1920s to the 1950s, including Saul Bass, Lester Beall, Alexey Brodovitch, Tom Carnese, William Golden, Rob Roy Kelly, Alvin Lustig, Cipe Pineles, Ladislav Sutnar, and Bradbury Thompson. Complementing the design artifacts are sketches, correspondence, and other materials that help paint a broader picture of each designer.

The Doris and Henry Dreyfuss Study Center Library and Archive

On the third floor of New York’s Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum › 120 is a 70,000-volume array of books, periodicals, catalogs, and trade literature dating from the fifteenth through the twentieth centuries, including work from graphic designers like Ladislav Sutnar › 150 and Paula Scher › 182 and the design firm M&Co. › 183. For those looking for more depth, a collection of 750 pop-up and movable books is also available.

Archival boxes used to store each font individually

Arts of the Book Collection at Yale

As part of the Yale University Library system, the Arts of the Book Collection contains close to one million bookplates, a large collection of design ephemera, advertising cards, and volvelles (graphic wheels), among other material. It also provides access to the masters theses of graphic design program students since 1952. Parallel to a donation from Marion Rand of her late husband’s work to the Department of Manuscripts and Archives in the Sterling Memorial Library, the Arts of the Book Collection holds around 200 books from Paul Rand’s › 159 personal library.