KNOWLEDGE

In Classrooms

While students can and should make use of the very best of the higher education available to them, it is difficult to deny that some educational institutions consistently deliver results by offering access to an effective faculty roster and facilities as well as by continually producing graduates brimming with professional preparation. And just as graphic design can manifest in an infinite number of ways—as opposed to, say, accounting, where there is a right or wrong answer—an education in graphic design is as varied and peculiar, with each program taking on the personalities and beliefs of its directors and faculty, giving students ample choice among the theories and methodologies that will best help them develop their own.

BV (BEAULIEU VINEYARD) WINE / Jin Young Lee; instructors, Bryony Gomez-Palacio, Armin Vit / USA, 2007

Basel School of Design

In 1942, Emil Ruder was hired by the Allgemeine Gewerbeschule (General Vocational School) to teach typography to typesetting and printer apprentices, and in 1946 Armin Hofmann › 152 joined the faculty to help establish the graphic design program, the Schule für Gestaltung Basel (Basel School of Design), that would become influential for students like Steff Geissbuhler › 157, Karl Gerstner, Hans-Rudolf Lutz, Yves Zimmerman, and numerous other designers. Hofmann’s approach—a foundation in the basics as explored through exercises of “repetition, intensification, contrast, and dispersion”—was documented in Graphic Design Manual: Principles and Practice, published in 1965, and many of those exercises can now be found in numerous schools.

In 1968, after more than a decade of Ruder conducting informal postgraduate study in typography with two or three students a year, the Advanced Class of Graphic Design (Weiterbildungsklasse für Graphik) was established as an official international graduate design program with seven new students. It introduced Wolfgang Weingart › 178, a former student, as one of the teachers, who took the program into new directions as he questioned established typography practice and the rules that governed it. His effervescent approach to teaching typography attracted a new generation of designers like Americans Dan Friedman and April Greiman › 179, who imported this typographic impetus. In 2000, a split left two Basel schools of design, one now affiliated with the University of Applied Sciences Northwestern Switzerland as an accredited program, the other remaining a vocation school. This vocational school has also hosted the Basics in Design and Typography summer program since 2005, with Weingart as one of the teachers and the intention of keeping the legacy of the Weiterbildungsklasse alive.

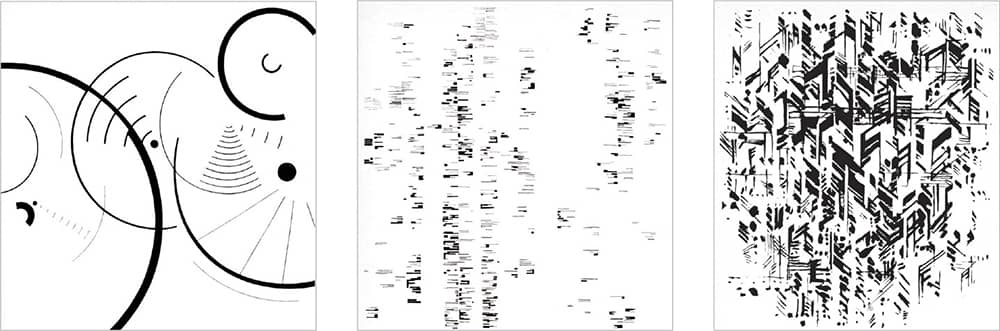

BLACK AND WHITE EXERCISES EXPRESSING A SERIES OF THEMES: BICYCLE TRAFFIC, BIRCH TREES, MUSIC / Steff Geissbuhler; instructors, Armin Hofmann, Verlag Arthur, Niggli AG / Switzerland, 1958–1964

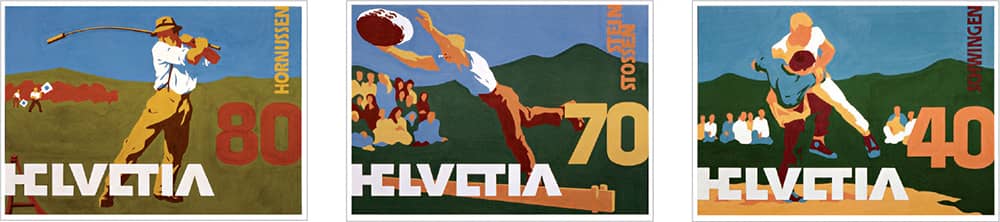

POSTAGE STAMPS HIGHLIGHTING THE SWISS FOLK SPORTS OF HORNUSSEN (A LOOSE CROSS BETWEEN GOLF AND BASEBALL), STEINSTOSSEN (STONETHROW), AND SCHWINGEN (FOLK WRESTLING) / Joachim Müller-Lancé; instructor, Max Schmid / Switzerland, 1982–1986

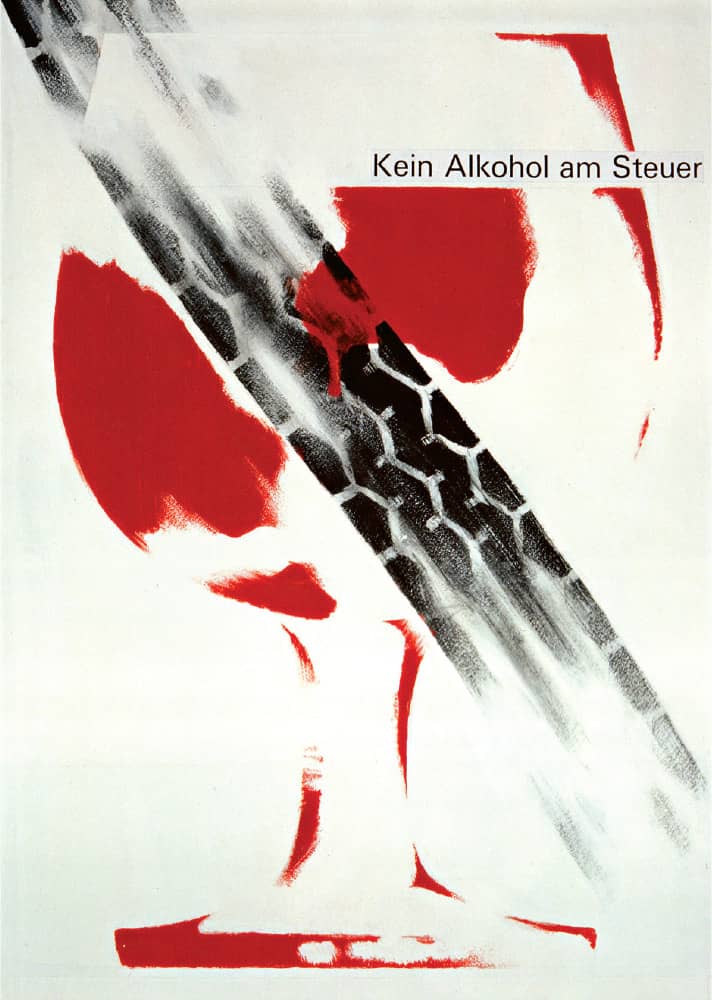

NO ALCOHOL AT THE WHEEL POSTER FOR THE CITY OF BASEL / Joachim Müller-Lancé; instructor, Armin Hofmann / Switzerland, 1982–1986

RHYTHM IN JAZZ AND IN NEW WAVE WORDMARK / Joachim Müller-Lancé; instructor, Christian Mengelt / Switzerland, 1982–1986

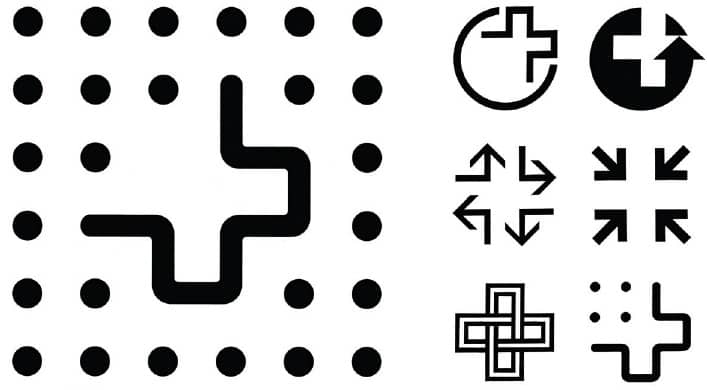

SWISS SOCIETY FOR INTER-REGIONAL COOPERATION LOGO / Joachim Müller-Lancé; instructor, Armin Hofmann / Switzerland, 1982–1986

Yale School of Art

As a book designer and avid typographer, Alvin Eisenman was offered a position with Yale University Press and a supplemental teaching position at the university’s art school, leading to the establishment of the first graduate studies program in graphic design (graphic arts, as it was first called) in the United States in 1950 in New Haven, Connecticut. Under Eisenman, who held the position of program director until 1990, the graduate program attracted some of the leading practitioners of the time, including Armin Hofmann (who taught there for 30 years and helped established strong ties with the Basel School of Design › 128), Alexey Brodovitch › 143, Alvin Lustig › 144, Herbert Matter, Bradbury Thompson, and, of course, Paul Rand › 159, who started as a visiting critic in 1956 but soon after became a faculty member and stayed until 1993.

While the program had just a handful of full-time faculty members, its affluent influx of visiting designers and critics enrich the student experience and is a model that continues today. In 1990, Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, a 1964 graduate of the program, was appointed Eisenman’s successor—with an unfortunate dose of controversy, as Rand and other members resigned in disapproval of the decision. She has fostered a new generation of visiting designers and critics including Michael Bierut › 203, Matthew Carter › 221, Jessica Helfand, Allen Hori, and Scott Stowell, as well as foreigners like Irma Boom › 193, Armand Mevis, and Linda van Deursen. With an inquisitive approach fostered by de Bretteville, students explore topics of personal interest, and their ideas become part of the work—indeed a harsh distancing from the modernist and functional underpinnings of the previous generation. Regardless of era, Yale’s graduate program prepares its students to excel in the changing climate of graphic design.

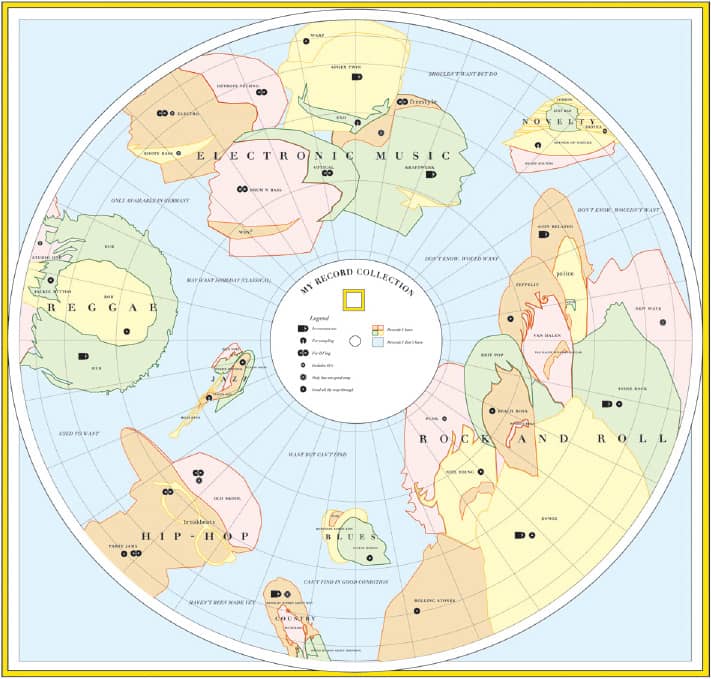

RECORD COLLECTION MAPPING / Dmitri Siegel; instructor; Barbara Glauber / USA, 2002

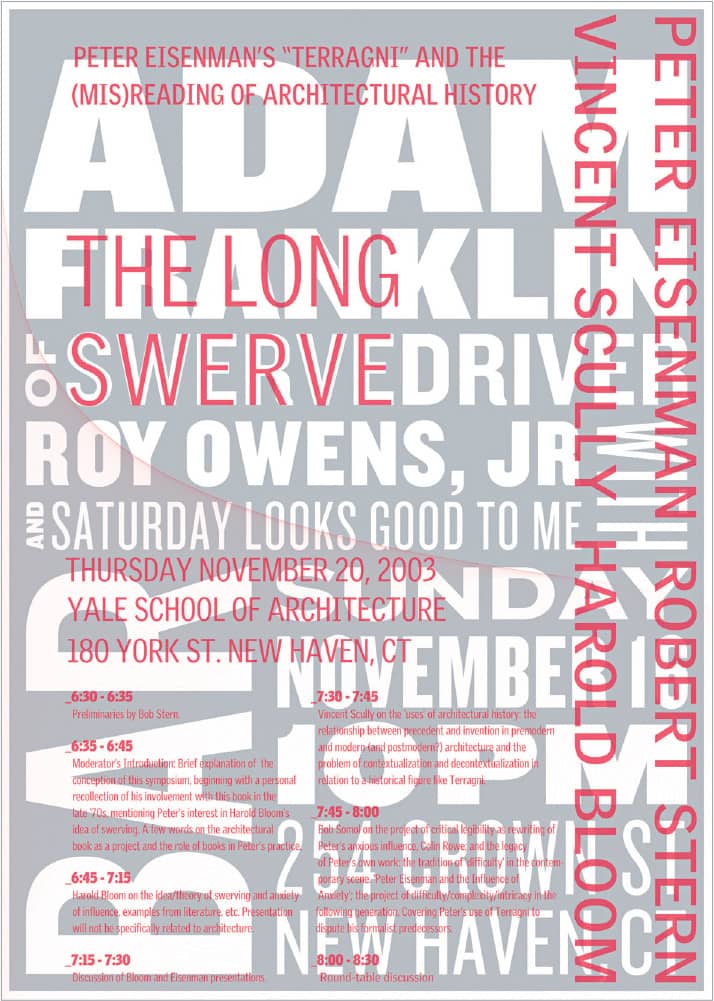

YALE UNIVERSITY AND SWERVEDRIVER BAND SIMULTANEOUS EVENT POSTER / Dmitri Siegel; instructor; Armand Mevis / USA, 2002

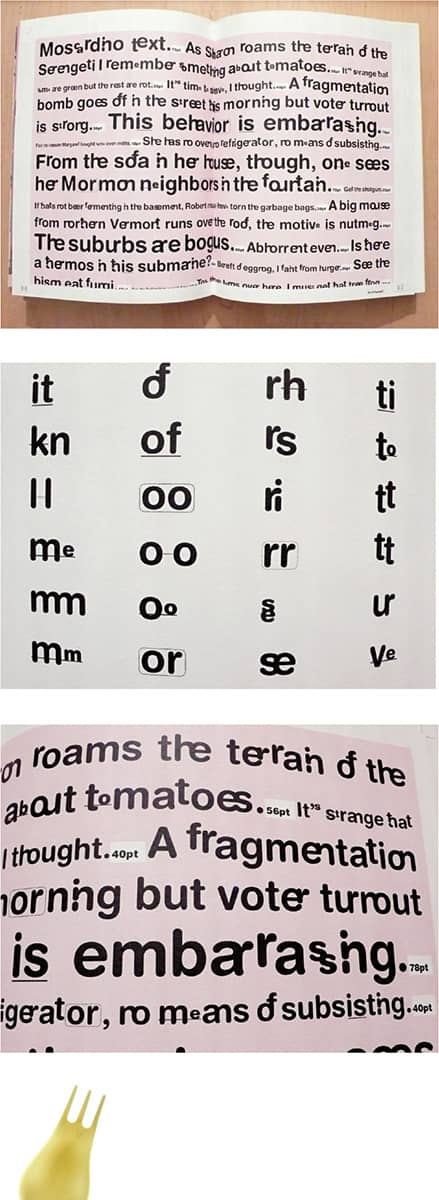

INSPIRED BY AN ITALIAN SPORK AND BASED ON HELVETICA ROUNDED, THE MOSCARDINO TYPEFACE EXPLORES LIGATURES WELL BEYOND THE EXPECTED / Tracy Jenkins; instructors, Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, Susan Sellers / USA, 2003

Cranbrook Academy of Art

No classes. No teachers. No projects. This is the modus operandi of the graduate program in two-dimensional design at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, where students define their own projects, rely on each other for critiques, and work with an artist-in-residence and visiting designers to realize their self-directed projects. This model and the resulting work of the graphic design students since the 1980s has long attracted the attention, both positive and negative, of the industry. In 1971, Michael and Katherine McCoy › 185 were hired to run a joint two-dimensional/three-dimensional program; their teaching drew from their experience in Swiss design and modernism.

However, in the late 1970s, the notions of postmodernism and the vernacular in architecture started to seep in as influenced by Robert Venturi, and, during the 1980s, the critical theory and the writings of Roland Barthes and Jacques Derrida. These led to the exploration of deconstruction and poststructuralist ideas through design strategies by students like Andrew Blauvelt, Ed Fella › 185, Jeffery Keedy, and Allen Hori. Much of the work was largely bulked as a postmodernism aesthetic without further consideration; nonetheless, there is a fluctuating yet discernable texture to its students’ work.

In 1995, two Cranbrook graduates, P. Scott and Laurie Haycock Makela, were appointed designers-in-residence after the McCoys. They continued the legacy of exploration, now accentuated by digital design online and motion graphics, and infused an energy all their own, attracting designers from around the world. Unfortunately, their time at the academy was cut short by Scott’s death in 1999, although Laurie continued until 2001. Elliot Earls, another graduate, then took on the position, leading the exploration in a field where boundaries in media and disciplines are easier to cross. Then again, that has never been a limitation.

Above and right TO THE LOSS OF OUR PRINCESS, THESIS PROJECT / Cinderella’s tombstone, handlettered and built with precision-machined resin / Catelijne van Middelkoop / USA, 2001–2002 / Photos: Ryan Pescatore Frisk

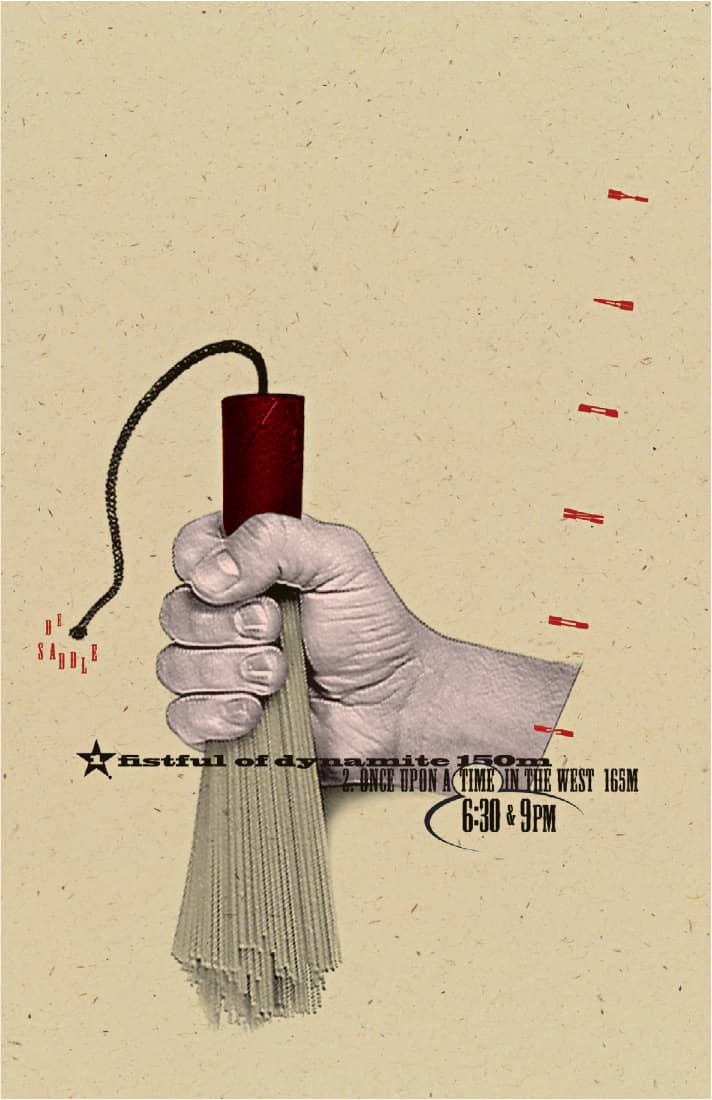

CRANBROOK’S SPAGHETTI WESTERN STUDENT FILM SERIES POSTER / Doug Bartow; instructor, Katherine McCoy / USA, 1994

HEY DUTCHIE! TYPE SPECIMEN POSTER / Catelijne van Middelkoop / USA, 2001–2002

EYECANDY POSTER / Doug Bartow; instructor, Katherine McCoy / USA, 1995

California Institute of the Arts

With degrees from Cranbrook Academy of Art › 130 in 1975 and the Yale graduate program › 129 in graphic design in 1982, a brief stint at Vignelli Associates › 160, a teaching position at the University of Houston’s architecture and graphic design departments, and a burgeoning interest in design history and education, Lorraine Wild brought a comprehensive background to renew the graphic design program at California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) in Valencia when she was appointed its director in 1985. Soon after, Cranbrook graduates Jeffery Keedy and Ed Fella › 185 joined the faculty, bringing their exploratory outlook into a structured program informed by history and theory. CalArts has benefited over the years by a faculty made up, in part, by active practitioners—as graphic designers, writers, curators—like Caryn Aono, Anne Burdick, Geoff Kaplan (a Cranbrook graduate), Michael Worthington, and Louise Sandhaus and Gail Swanlund, who have both also acted as program directors.

CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF THE ARTS GRAPHIC DESIGN DEPARTMENT END-OF-YEAR SHOW / Ryan Corey, Lucas Quigley; instructor, Gail Swanlund / USA, 2005

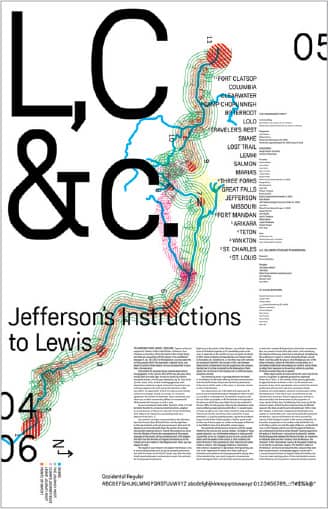

OCCIDENTAL TYPEFACE SPECIMEN POSTER / Ryan Corey; instructor, Greg Lindy / USA, 2005

A WORK OF SOME AESTHETIC AND SPIRITUAL VALUE POSTER / Ryan Corey; instructor, Gail Swanlund / USA, 2005

.1–10 TYPOGRAPHIC HIERARCHY PROJECT: ZAHA HADID LISTENS TO THE MAGNETIC FIELDS / Ian Lynam; instructor, Jeffery Keedy / USA, 2003

ARTIST LECTURE, YEHUDIT SASPORTAS POSTER SET / Ian Lynam; instructor, Ed Fella / USA, 2004

Cooper Union

The Cooper Union School of Art is one of the three schools that make up the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, New York’s prestigious institution that admits a select group of undergraduates and offers them a full-tuition scholarship for their four-year stay. The rigorous admission process includes an ever-changing “home test” that tasks applicants on a variety of exercises, ensures the seriousness of the candidates, and gives the school the honor of having one of the lowest acceptance rates in the nation. So it must come as no surprise that Cooper Union has proven a fertile ground for the industry. Some of its most iconic practitioners have graduated from its halls, including the founding members of Push Pin Studios › 168 Seymour Chwast, Reynold Ruffins, Edward Sorel, and Milton Glaser, as well as Herb Lubalin › 167, Lou Dorfsman › 173, Ellen Lupton › 240, Abbott Miller, and Stephen Doyle, among others.

SEE EMILY ROZ HERB LUBALIN STUDY CENTER EXHIBITION AT THE COOPER UNION SCHOOL OF ART / Seth Labenz and Roy Rub; instructor, Mike Essl / USA, 2006

TICKET TO DESIGN PRELIMINARY BUSINESS CARDS FOR SETH LABENZ AND ROY RUB / Seth Labenz, Roy Rub; instructor, Mike Essl / USA, 2006

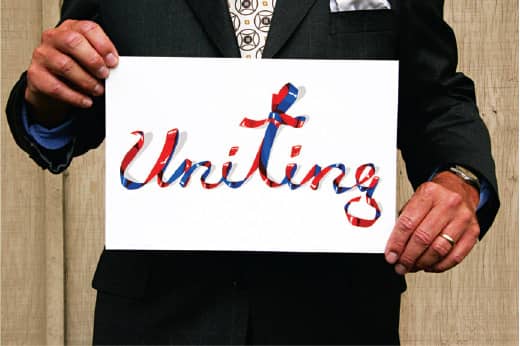

UNITING, GIFT RECEIVED BY EVERY MEMBER OF THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS IN SUPPORT OF THE UNITING AMERICAN FAMILIES ACT [S.1278] / Seth Labenz, Roy Rub; instructor, Stefan Sagmeister / USA, 2006

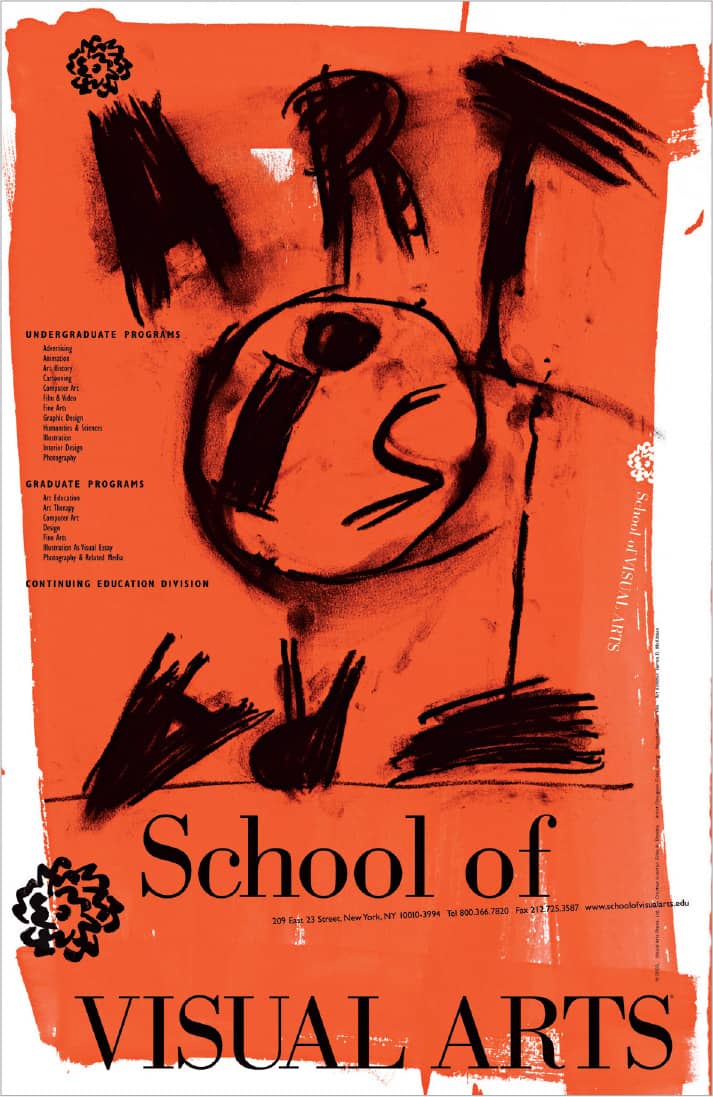

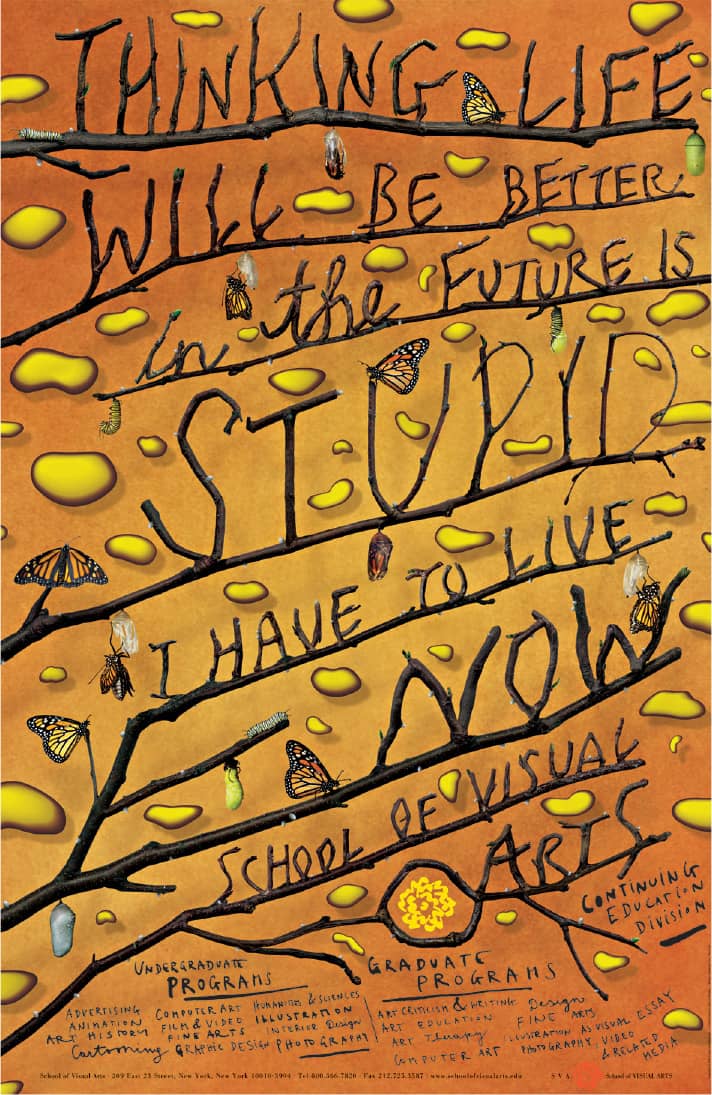

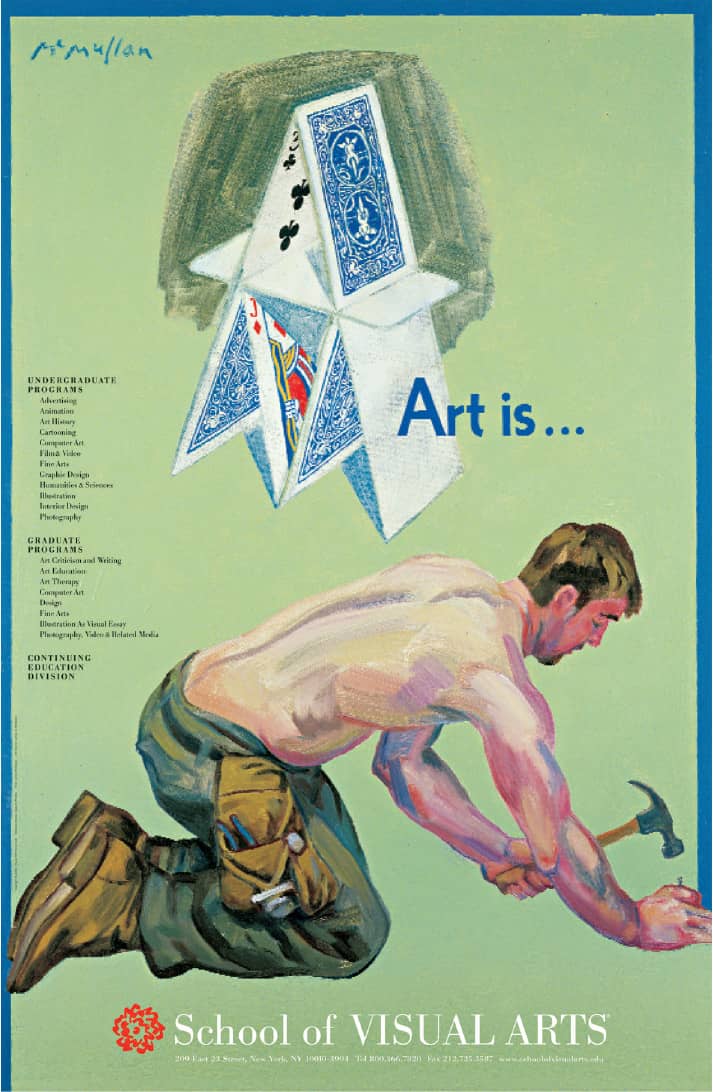

School of Visual Arts

Co-founded in 1947 as the Cartoonists and Illustrators School by Burne Hogarth and Silas H. Rhodes, the School of Visual Arts (as it was later renamed in 1955) was, from the beginning, set up so its faculty would be comprised solely of professional, working designers. Hogarth left in 1970, but Rhodes stayed involved with the school—as its president for six years in the 1970s, as a chairman of the board, and as a creative director of both the Visual Arts Press Ltd. and the numerous recruitment posters deployed in the city’s subway system for 55 years (see right)—until his death in 2007. The majority of the school’s 3,000-plus undergraduate students are enrolled in the graphic design program, where they are taught by more than 100 professional designers including Paula Scher › 182, Carin Goldberg, James Victore, Paul Sahre, Louise Fili › 197, and Debbie Millman.

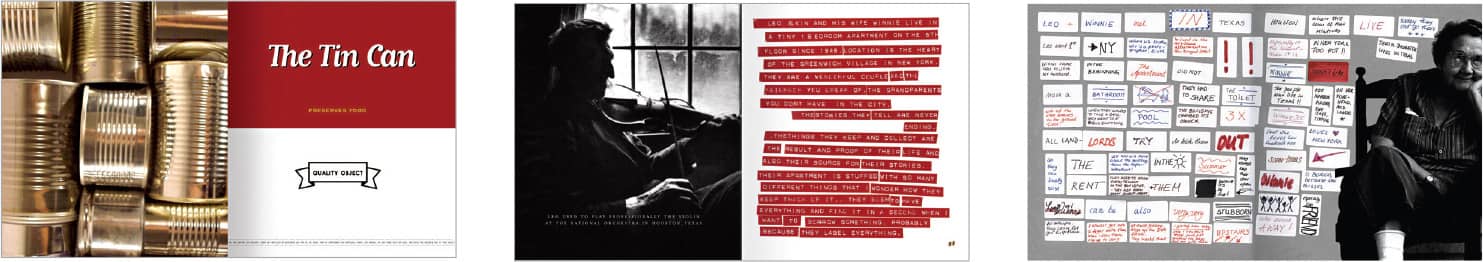

QUALITY MAGAZINE / Julia Hoffmann; instructor, Carin Goldberg / USA, 2001–2002

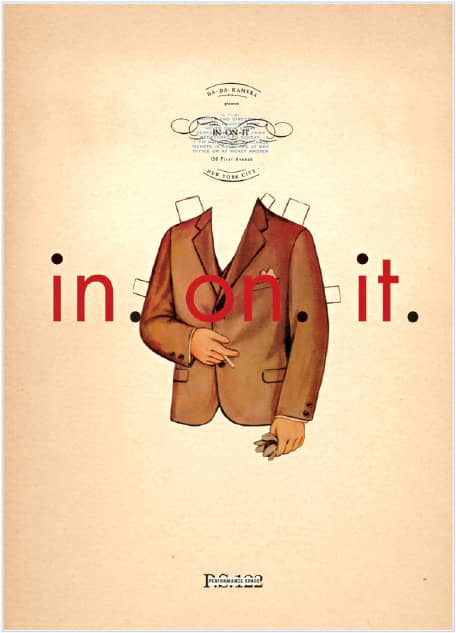

IN ON IT POSTER FOR P.S. 122 / Julia Hoffmann; instructor, Carin Goldberg / USA, 2001–2002

CAFÉ PARCO BRANDING / Jin Young Lee; instructors, Bryony Gomez-Palacio, Armin Vit / USA, 2007

School of Visual Arts MFA Designer as Author

In 1997, the Designer as Author graduate program from the School of Visual Arts was co-founded by Steven Heller › 238 and Lita Talarico, both of whom still co-chair the program. As in the undergraduate program, professional designers and writers—like Brian Collins › 204, Milton Glaser › 170, Stefan Sagmeister › 202, and Véronique Vienne—make up the faculty that gathers in the evenings with the dozen or more students to develop a viable concept through any means necessary and take it to a point where it could be commercially produced and marketed or publicly accessible. Because of this focused premise, many of the program’s students have the ability to make an instant impact with consumer-ready projects, like Deborah Adler’s ClearRX › 318 package for Target and Jennifer Panepinto’s beautiful Mesü porcelain bowls for food measuring.

ABYSSINIAN BAPTIST CHURCH OF HARLEM IDENTITY, COLLATERAL, AND ADVERTISING / thesis project turned reality and further aided by the Sappi Ideas That Matter Grant / Bobby C. Martin Jr.; thesis advisor, Paula Scher; instructors, Steven Heller, Brian Collins, Dorothy Globus, Martin Kace / USA, 2003

THE AMAZING PROJECT, WHERE AMAZING PEOPLE DO AMAZING THINGS TO CHANGE THE WORLD / Randy J. Hunt; thesis consulting, Brian Collins, Gail Anderson; thesis adviser, Mark Randall / USA, 2006 / Photo: Adam Krause

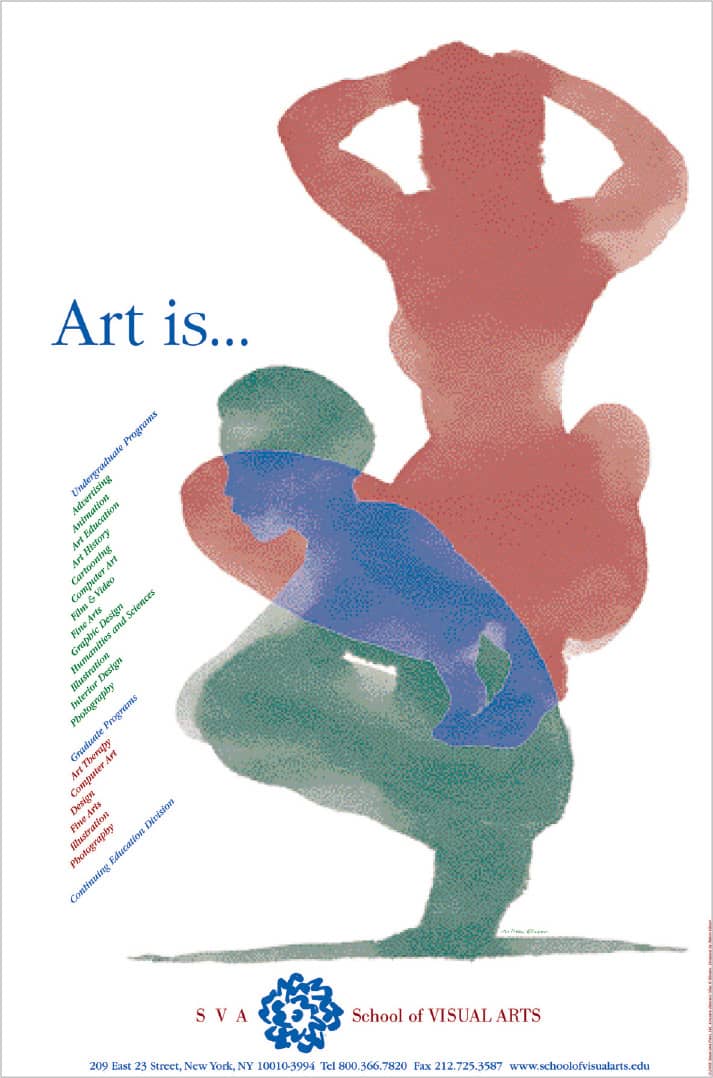

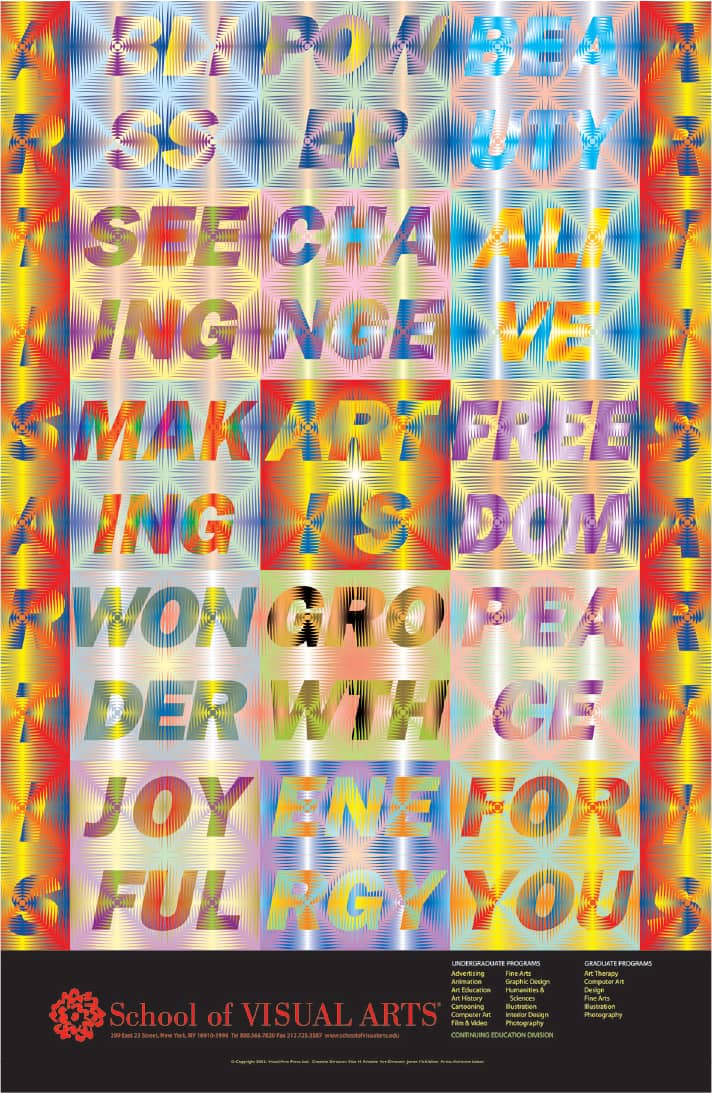

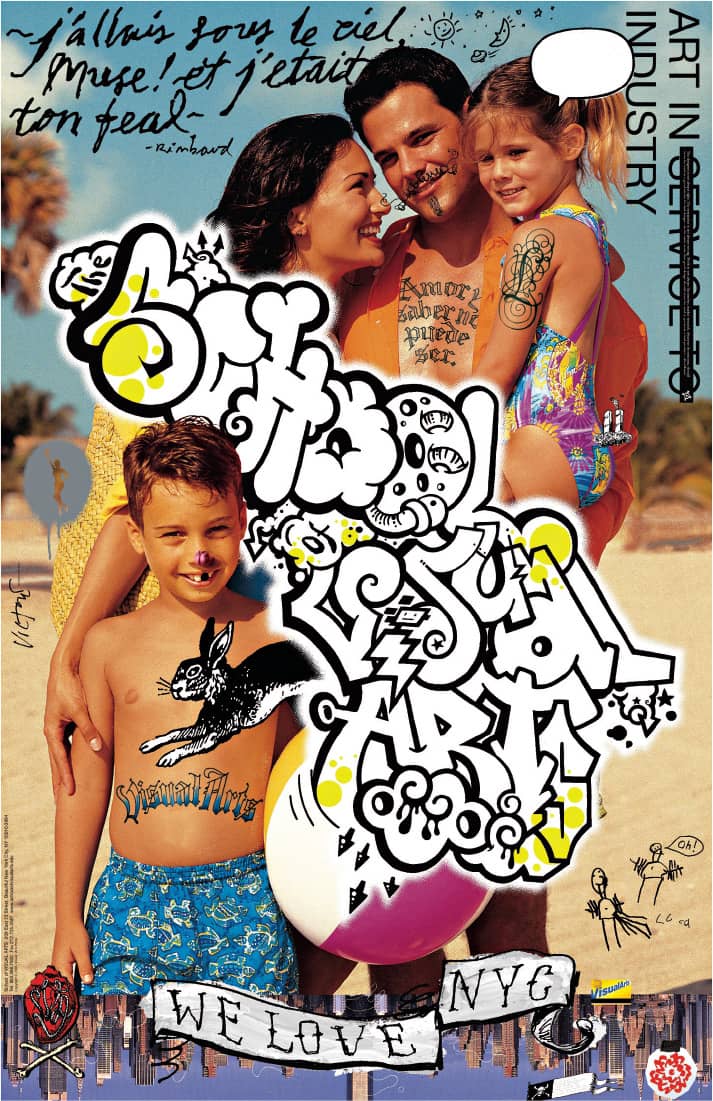

School of Visual Arts Subway Posters

Art direction, Silas H. Rhodes; design, Milton Glaser / USA, 2000

Art direction, Silas H. Rhodes; design, Adrienne Leban / USA, 2002

Art direction, Silas H. Rhodes; design, James Victore / USA, 2003

Art direction, Silas H. Rhodes; design, Frank Young / USA, 2003

Art direction, Silas H. Rhodes; design, Stefan Sagmeister / USA, 2004

Art direction, Silas H. Rhodes; design, James McMullan / USA, 2004

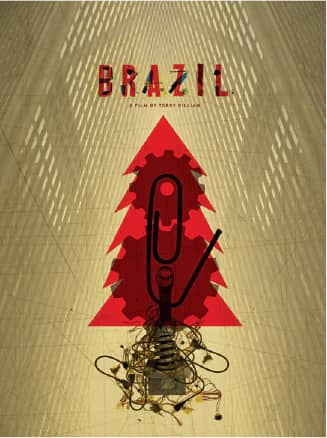

Rhode Island School of Design

BRAZIL FILM POSTER / Kai Salmela; instructor, Dietmar Winkler / USA, 2006

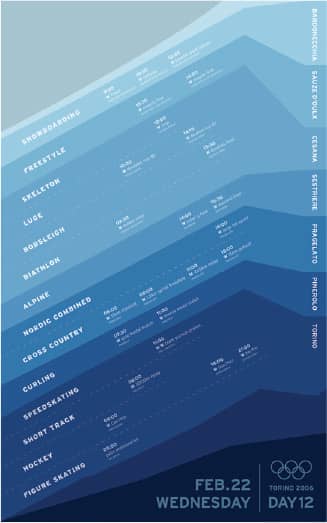

TORINO SUMMER OLYMPIC GAMES SCHEDULE POSTER / Kai Salmela; instructor, Doug Scott / USA, 2007

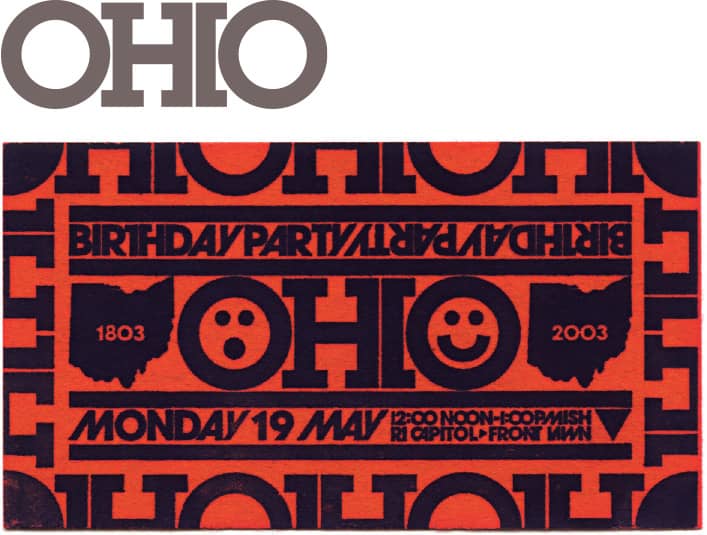

OHIO BICENTENNIAL CELEBRATION IDENTITY / Joe Marianek; instructors, Douglass Scott, Lucinda Hitchcock / USA, 2003

RISD STICKER 2003 YEARBOOK / Joe Marianek, Adriana Deléo, Wyeth Hansen, Ryan Waller, Lily Williams; instructors, Douglass Scott, Lucinda Hitchcock / USA, 2003

Maryland Institute College of Art

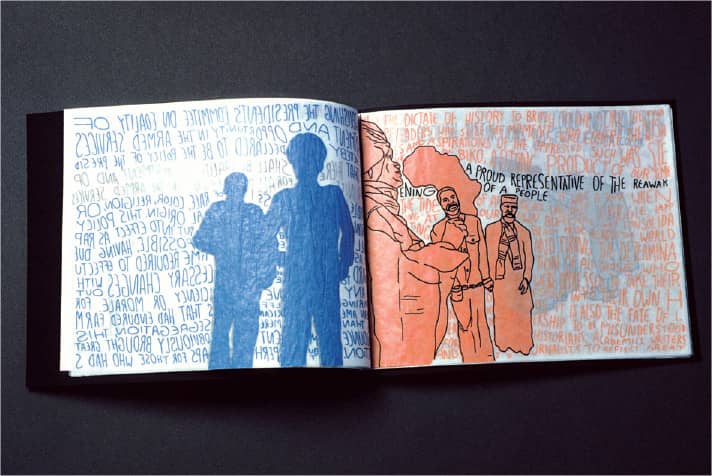

BLACKS IN WAX ARTIST BOOK / Silkscreened on transparent wax-like paper / Bruce Willen; instructor; Jennifer Cole Philips / USA, 2001

WHOLESOME FOODS PACKAGING / Bruce Willen; instructor; Jennifer Cole Philips / USA, 2001

SMALL ROAR GRADUATE THESIS PROJECT / Upon the birth of their daughter, Mike and Stephanie Weikert opened for business / Mike Weikert / USA, 2005

Portfolio Center

DECECCO REBRANDING AND PACKAGING / Sam Potts; instructor, George Gall / USA, 2000 / Photo: Lisa Devlin

EXODUS, PROMOTIONAL PIECE FOR ADOBE’S JOANNA / Sam Potts; instructor, Hank Richardson / USA, 1999 / Photo: Lisa Devlin

CAUSE + EFFECT SELF-CURATED EXHIBITION CATALOG / Sam Potts; instructor, Melissa Kuperminc / USA, 2000 / Photo: Lisa Devlin

IMPACT CHAIR, REFLECTING A PERSONAL EXPERIENCE FROM 9/11 / Dave Werner; instructor, Hank Richardson / USA, 2006

MONDAVI WINE PACKAGING / Dave Werner; instructor, Hank Richardson / USA, 2006

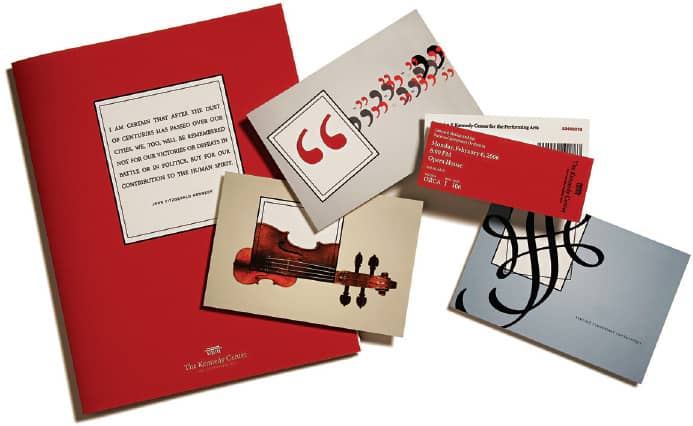

KENNEDY CENTER PROMOTIONAL SUITE / Dave Werner; instructor, Nicole Riekki / USA, 2006

Royal College of Art

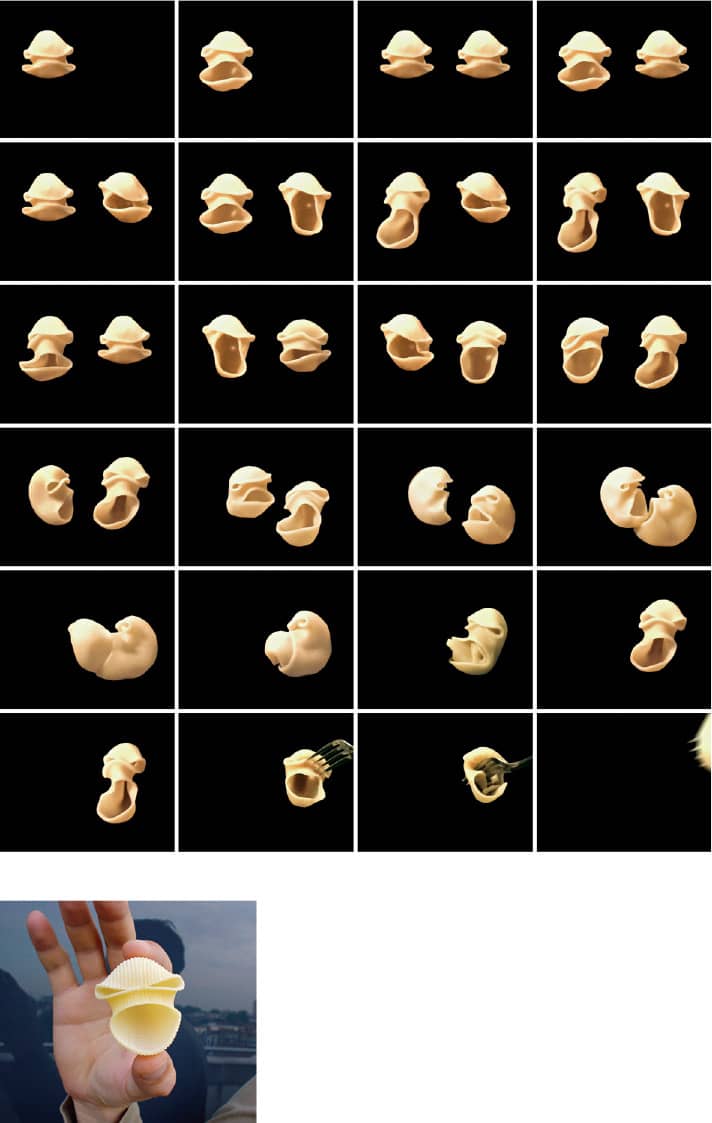

EAT OR BE EATEN SINGING PASTA ANIMATION / Tomi Vollauschek / UK, 2000

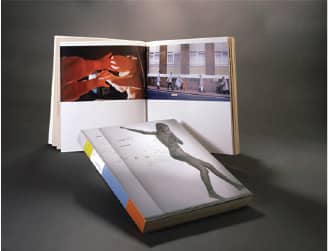

TRANS-FORM MAGAZINE / FL@33: Agathe Jacquillat, Tomi Vollauschek; advisors, Gert Dumbar, Russell Warren-Fisher / UK, 2001

Central Saint Martins College of Art & Design

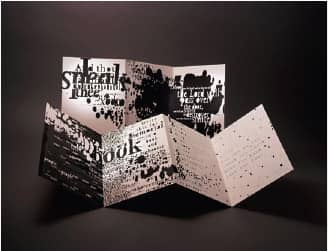

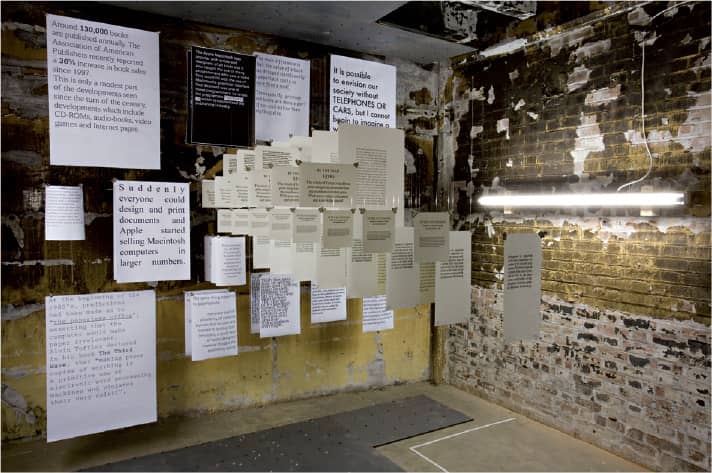

THE EVOLUTION OF PRINT, AN INSTALLATION SHOWCASING THE EXPLOSION OF KNOWLEDGE FROM THE START OF LETTERPRESS TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY / Diego Ulrich; instructor, Max Ackermann / USA, 2008

THREE-DIMENSIONAL AILERON TYPEFACE FOR USE IN OPEN SPACES / Diego Ulrich; instructor, Max Ackermann / USA, 2008

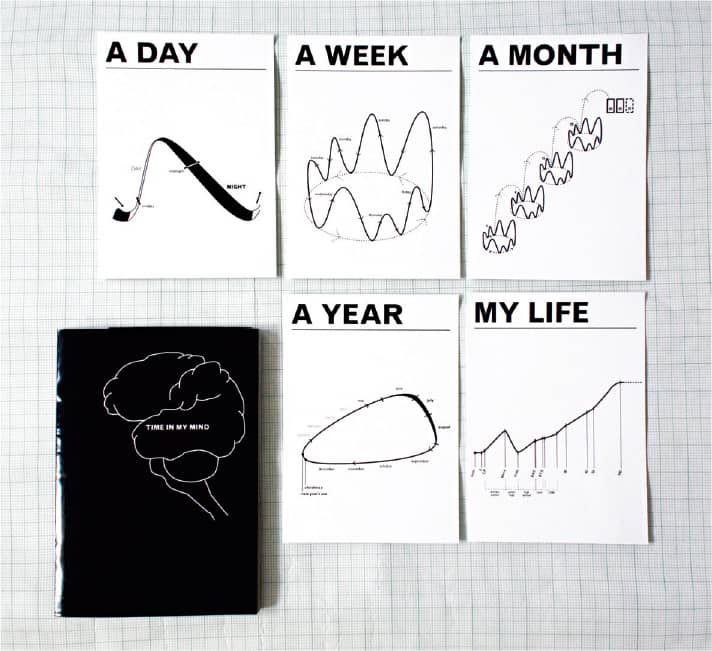

INFORMATION GRAPHICS ON THE REPRESENTATION OF TIME AS IT IS FELT / Clara Brizard; instructor, Sara De Bondt / UK, 2008

BEYOND MY WINDOW, DIE FENSTER SERIES OF DIE-CUT AND SCREENPRINTED POSTERS / Clara Brizard; instructor, Sara De Bondt / UK, 2008

University of Reading, MA in Typeface Design

MAIOLA / Released by FontFont in 2005 / Veronika Burian; instructors, Gerry Leonidas, Gerard Unger / USA, 2003

ARRIVAL TYPE FAMILY FOR UNIVERSITY OF READING / Released in 2005 / Keith Chi-hang Tam; instructors, Gerry Leonidas, Gerard Unger / UK 2001–2002