The focus of this chapter is on differences of opinion. Where the future is concerned there are no right or wrong answers. What there are, are choices; only hindsight will prove any choice to be a good one or a poor one. The advice in this chapter will help you to join in the key conversations that always accompany controversial change and decision making within your organisation; it will do so in a way that ensures your voice is heard and you are not marginalised.

WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT?

In the workplace, organisational politics are a fact of life. Organisations, being made up of people, are essentially political institutions. All business professionals need to be adept at dealing with political situations, but some are better at it than others.

Unfortunately, there is, however, no single formula for success. Politics are often messy, ambiguous and unpredictable; and to top it all, being right is not enough. Outcomes in the political arena depend upon the subtle interactions and interplays between people. Each situation will be different and unique, and what proves successful in one situation may prove disastrous in the next. In essence, organisational politics are an art, rather than a science!

Political acumen is a key skill for anyone wanting to ‘get things done’, to have influence over others, to invoke change, to make an impact and to build and maintain their reputation.

Organisational politics are often construed as being destructive, time wasting or unethical. Ask anyone what words and phrases spring to mind when you mention the words ‘organisational politics’ and, 9 times out of 10, you will get responses such as:

• doing deals;

• scoring points;

• personal agendas;

• getting one over on one’s colleagues;

• secrecy and subterfuge;

• mafioso tactics;

• win–lose situations.

Organisational politics are, however, simply the result of differing opinions, values, standpoints, perceptions and so on. As such, they can be dealt with either positively or negatively. On the positive side, organisational politics are about:

• influence;

• collaboration;

• building relationships;

• openness and honesty;

• being streetwise;

• win–win situations.

![]()

Participating in organisational politics is not an option, but how you choose to participate is. The choice is yours, either positively or negatively, and the outcomes are of your own making.

Researchers Baddeley and James studied leaders who had attained long-term political success within their organisation.1 The leaders attributed their success to the following two key dimensions:

• acting from an informed and knowledgeable position that demonstrates:

![]() an understanding of the decision-making processes of your organisation;

an understanding of the decision-making processes of your organisation;

![]() an awareness of the overt and covert agendas of the key decision makers;

an awareness of the overt and covert agendas of the key decision makers;

![]() an innate understanding of who has the power and what gives them that power;

an innate understanding of who has the power and what gives them that power;

![]() a willingness to go that extra mile to help others even if it is not part of your job description;

a willingness to go that extra mile to help others even if it is not part of your job description;

![]() an understanding of the style and culture of your organisation;

an understanding of the style and culture of your organisation;

![]() a sense of the meaning of ‘politics’ in the context of your organisation;

a sense of the meaning of ‘politics’ in the context of your organisation;

• acting with integrity as defined by the following principles:

![]() avoiding playing psychological games with people;

avoiding playing psychological games with people;

![]() accepting yourself and others as human beings who all have their associated strengths, weaknesses, peculiarities, quirks and imperfections;

accepting yourself and others as human beings who all have their associated strengths, weaknesses, peculiarities, quirks and imperfections;

![]() seeking to find win–win strategies in situations of difficulty or conflict.

seeking to find win–win strategies in situations of difficulty or conflict.

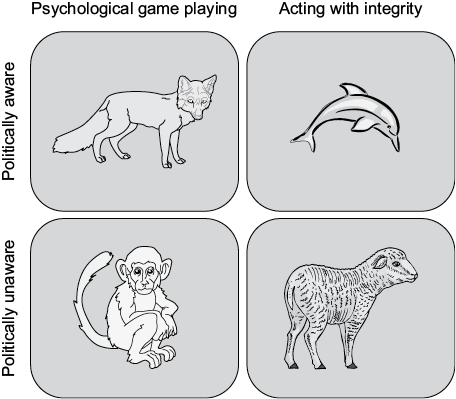

The model in Figure 4.1 utilises these two dimensions and is adapted from the work of Baddeley and James. Each quadrant of the model is illustrated with an animal analogy to create a political zoo. The innocent sheep acts with integrity, but has no clue about what is going on in the organisational sense. The clever fox knows precisely what is going on, but uses this knowledge to exploit the weaknesses of others. The inept baboon neither acts with integrity nor knows what is going on. The wise dolphin possesses both understanding and integrity and hence represents our icon of political success. The behaviour of the four animals is described below in greater detail.

Figure 4.1 Political zoo2

The sheep sees the world through simplistic eyes. Sheep believe you are right if you are in a position of authority. They do what they are told, stick to the rules, are too busy to network and don’t know how to build coalitions and alliances. They act with integrity, but are street-naïve.

The fox knows exactly what is going on, but uses this knowledge to exploit the weaknesses in others. Foxes are self-centred but with a charming veneer. They are manipulative and like games involving winners and losers, and love leading lambs to the slaughterhouse.

The baboon is not tuned into the grapevine. Baboons’ reception of outside signals is blocked and they therefore end up conspiring with the powerless. They are emotionally illiterate, seeing things in black and white and not recognising when they are fighting a losing battle. They play games with people, but don’t understand why they keep losing.

The dolphin takes account of other people personally. Dolphins are excellent listeners and aware of others’ viewpoints. They are non-defensive, open, and share information. They use creativity and imagination to engineer win–win situations. They act from both an informed and an ethical standpoint; they are both streetwise and virtuous.

![]()

What characterises dolphins is calmness in a storm, a certainty about their own destiny and a thirst to learn from others. They may be busy, but not stressed or pressured; and they can always find the time to work alongside colleagues or help others out. People have respect for them as model human beings first, and for their competence in their professional capacity second.

PRACTICAL ADVICE

You will inevitably behave as each of the four animals from time to time; however, it is your default position or your prime behaviour that counts. The aim of this book is to help you move to the top of the model; left or right is, however, your choice. We sincerely hope, though, that your aim would be to become a ‘dolphin’. Here are a few examples of how the four animals would behave in various situations:

• When in situations of conflict

![]() The dolphin asks, ‘How can we work together to solve this one?’

The dolphin asks, ‘How can we work together to solve this one?’

![]() The fox asserts, ‘I am not prepared to change my position.’

The fox asserts, ‘I am not prepared to change my position.’

![]() The baboon declares, ‘I can’t agree and would prefer not to discuss it anyway.’

The baboon declares, ‘I can’t agree and would prefer not to discuss it anyway.’

![]() The sheep mutters, ‘I concede the point and will accept whatever you say.’

The sheep mutters, ‘I concede the point and will accept whatever you say.’

• When responding to or giving orders

![]() The dolphin looks for opportunities to go beyond the call of duty, to extend their sphere of influence and to develop the potential in others.

The dolphin looks for opportunities to go beyond the call of duty, to extend their sphere of influence and to develop the potential in others.

![]() The fox demands, ‘Do as you are told – it’s my way or the highway.’

The fox demands, ‘Do as you are told – it’s my way or the highway.’

![]() The baboon protests, ‘That’s outside my brief – I won’t do it.’

The baboon protests, ‘That’s outside my brief – I won’t do it.’

![]() The sheep says meekly, ‘I will do as you say.’

The sheep says meekly, ‘I will do as you say.’

• When communicating with others

![]() The dolphin actively listens, is open and shares information.

The dolphin actively listens, is open and shares information.

![]() The fox is dismissive of alternative viewpoints, looks for a fight and believes that information is power.

The fox is dismissive of alternative viewpoints, looks for a fight and believes that information is power.

![]() The baboon whinges and moans to others who are equally powerless.

The baboon whinges and moans to others who are equally powerless.

![]() The sheep keeps its head down and keeps quiet about anything potentially controversial.

The sheep keeps its head down and keeps quiet about anything potentially controversial.

• When considering the phrase ‘organisational politics’

![]() The dolphin believes that organisational politics are a fact of life and are about influence, collaboration and achieving win–win outcomes.

The dolphin believes that organisational politics are a fact of life and are about influence, collaboration and achieving win–win outcomes.

![]() The fox believes that organisational politics are a sport. They are about winners and losers and about coming out on top; they involve manipulation and exploitation to achieve one’s own ends.

The fox believes that organisational politics are a sport. They are about winners and losers and about coming out on top; they involve manipulation and exploitation to achieve one’s own ends.

![]() The baboon believes that organisational politics are a game, but doesn’t understand why it keeps losing.

The baboon believes that organisational politics are a game, but doesn’t understand why it keeps losing.

![]() The sheep believes that it does not enter into the game of organisational politics – it is just everyone else!

The sheep believes that it does not enter into the game of organisational politics – it is just everyone else!

Consider your own behaviour: which of the political animals best represents your behaviour today within your current role and which do you aspire to become? If ‘dolphinism’ is your aim, the five single most important things you can do are as follows:

• Develop your network – build positive relationships with anyone and everyone; create allies and advocates, build coalitions and alliances. Use your network to find out what is going on, to learn, to acquire those nuggets of wisdom and to tap into the organisational grapevine.

• Be someone that can be trusted – always do what you say you will do; never give people false hopes. Do not give empty promises because it is the easiest thing to do, and genuinely mean what you say. Remember, when it comes to trust, actions speak louder than words.

• Be generous – give a little of yourself to others, whether that is your time, your expertise, your knowledge, your help or your support, without expecting anything in return. Look for the positive in others, assume they have good intentions and stay curious to find out what these are even when they are not obvious or the person is behaving negatively. Be prepared to forgive and offer people a face-saving route if they need to change their minds or behave differently.

• Listen and learn – actively listen to others, focus on what they are saying rather than thinking about what you are going to say next. Accept what they say without judgement or criticism, try to put yourself in their shoes and view the situation from their perspective – you may learn something that surprises you. Remember that perception is reality in the eye of the beholder.

• Look for the win–win – if you want somebody to do something for you, always consider why they should do it: the ‘What’s in it for them?’ question. Think about why you do things that others have asked of you, or why you haven’t, as the case may be. It may be because you like the person, because it is an interesting task or because it will enhance your skills or reputation. It could be to gain ‘brownie’ points, because you owe someone, or to build trust or of course for many, many more reasons. People are far more likely to do something that you want them to do if there is something in it for them. Learn people’s motivators and tap into them; this way you will engage both hearts and minds.

![]()

Tom, an interim manager, had been brought in to help with the merging of two IT functions with dissimilar remuneration and benefit packages. Tom took the mantle of handling all the negotiations with representatives from both IT functions and also senior management. Through his openness and honesty, he struck an ‘affordable’ deal whereby everyone would receive some of the basic benefits straight away, for example free lunches, whilst remuneration packages would be slowly adjusted over a five-year period. He subsequently won the trust and support of everyone concerned. The departmental representatives ended up being the ones who outlined the deal and the process to their own colleagues.

Of all the animals, the fox is the one that is instantly recognisable and by far the most difficult to deal with, hence we will now focus on foxes.

Dealing with the foxes of the world

Foxes are self-centred, and senior ones are also invariably egotistical too whilst the more junior ones may be narcissistic. Your tactics for handling such individuals may include:

• Make them feel good about themselves:

![]() Help them to develop their skills and to shine at something.

Help them to develop their skills and to shine at something.

![]() Build on their suggestions – use the words ‘yes and …’ to steer them, rather than ‘yes, but …’.

Build on their suggestions – use the words ‘yes and …’ to steer them, rather than ‘yes, but …’.

![]() Help them to think through the consequences of their actions by using coaching-style questioning techniques.

Help them to think through the consequences of their actions by using coaching-style questioning techniques.

![]() Offer them the ‘limelight’.

Offer them the ‘limelight’.

![]() Massage their ego and praise their intellect.

Massage their ego and praise their intellect.

![]() Get them to talk about themselves – remember this is most people’s favourite subject. This will also have the added benefit of allowing you to get to know your ‘enemy’.

Get them to talk about themselves – remember this is most people’s favourite subject. This will also have the added benefit of allowing you to get to know your ‘enemy’.

• Make them feel comfortable about you:

![]() Help them to understand you – your values and drivers.

Help them to understand you – your values and drivers.

![]() Be truthful and transparent.

Be truthful and transparent.

• Don’t give them any ammunition:

![]() Be firm and strong.

Be firm and strong.

![]() Don’t be sloppy or slapdash.

Don’t be sloppy or slapdash.

![]() Keep your cool.

Keep your cool.

![]() Cultivate your friends – there is safety in numbers.

Cultivate your friends – there is safety in numbers.

![]() Cultivate allies – this will limit the fox’s sphere of influence.

Cultivate allies – this will limit the fox’s sphere of influence.

![]() Keep positive about yourself and maintain your values.

Keep positive about yourself and maintain your values.

![]()

Remember, always consider why anyone should do something for you: what’s in it for them?

The following mini case illustrates how a relatively junior IT manager successfully dealt with a fox and prevented a flawed change initiative from having a detrimental impact on his organisation.

![]()

A medium-sized financial services company had just implemented a new Customer Relationship Management (CRM) system; however, it had not delivered the anticipated business benefit. Indeed, in some quarters it had started to receive considerable criticism; most notably from the Banking Director, who claimed that productivity in his department had gone down since the implementation of the new system. The reason for this is that the new CRM system, being so much richer in (unused) functionality, takes 10 screens of form filling compared to the old system which used two. In addition, the new CRM system screens contain a significant number of redundant fields. So laborious is the form-filling process that staff are now writing details onto pieces of paper as they talk to customers, for fear that customers will get tired of waiting; they then enter the data after the customer has been dealt with. This is clearly not welcome to the Banking Director.

The new CRM system had cost some £20 million to implement and the Chief Information Officer (CIO) was keen to demonstrate a return on his investment. The CIO was considering his options, which were:

• To do nothing; the system was working and supporting the business need – why not put it down to experience?

• To spread the use of the system into the growing European operation – £20 million spread over the UK and the six continental European countries would soften the impact of the costs considerably.

• To spend more money and sort out the user interface issues – rationalising the number of screens and removing the redundant fields.

• To try to pass some of the blame onto the business for failing to adapt their processes to fit in with the new system.

The CIO in this case was a foxy character with an eye on promotion. His first reaction was to take option 4 but this was soon discounted as unrealistic. Therefore, option 2 became the CIO’s favoured route forward.

However, a relatively junior IT manager involved in the project challenged the CIO’s rationale. He followed the CIO to the coffee machine one day and started asking questions about the project; general ones to start – ‘What are your views on the new CRM system?’ – and then more specific questions, such as: ‘How do you believe we can improve our return on investment?’; ‘How much resistance do you perceive from the Europeans?’ (who didn’t want the new CRM and who could become powerful antagonists); and, ‘Could there be a better way of achieving value from the CRM?’

By asking such questions he helped the CIO to think through the consequences of his actions: that the CRM system was a solution looking for a problem, and that trying to force the Europeans to have something they didn’t want could backfire terribly and make the problem even worse. These factors would ultimately have a negative impact on the CIO’s own reputation.

Again through questioning, the junior manager then helped the CIO to come up with an alternative solution that was both a win for the company and a win for the CIO. They redeveloped the front end of the CRM system and packaged it up for sale elsewhere within the group – the Hong Kong office got something it desperately needed, the European operation was not forced to have something it did not want and the UK IT department became a profit centre. All these factors enhanced the reputation of the CIO.

Baboons can be dealt with in a similar way to foxes but they will be easier to negotiate with or neutralise – they have a tendency to ‘dig their own graves’.

Sheep are well meaning so can become targets for exploitation; you may therefore need to boost their self-confidence and protect them from the foxes of the world.

THINGS FOR YOU TO WORK ON NOW

Below are some questions that will help you build a picture of how tuned in you are to the way in which you behave and how your actions may be perceived and interpreted by your work colleagues.

![]()

KEY QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELF

• Within my current role, which of the political ‘animals’ do I believe I now behave most like, and which do I aspire to become?

• Do I always fulfil my promises; do my deeds always match my words?

• How extensive is my network and how much effort do I dedicate towards extending it?

• How aware am I of what goes on in the broader organisational context?

• How attuned am I to my organisation’s grapevine – am I the first or the last to find out what is afoot?

• How attuned am I to the personal agendas of my key stakeholders? Do I understand why they make the decisions that they do?

• Do I actively listen to others without judging?

• Do I openly share information?

• Do I do things for others without expecting anything in return?

Reflect on your answers to these questions and pick one aspect to work on over the next few weeks. To make this real, you need to think about your approach within the context of a real organisational situation within which there are winners and losers and actions are contested.

Below are some suggestions about things you can work on that will help you to better understand where you currently sit in the political zoo and how you can transition towards a set of political behaviours that help you influence situations in a positive way.

![]()

MINI EXERCISES YOU CAN TRY IMMEDIATELY

• Next time you are just about to agree to do something, reflect for a moment. Do you really intend to do it, are you totally committed, would you move heaven and earth to deliver? If you cannot answer yes to these questions, think again before you commit. Always doing what you say is habit-forming, too.

• Next time you ask someone to do something for you, think about what’s in it for them: why would they commit to doing it? Think about what you could offer them or how you could make it more appealing.

• Next time you wish to challenge someone’s thinking replace the word ‘but’ with an ‘and’.

• When a colleague makes a decision that you do not agree with, try to figure out their motives or rationale – ask them why they made the decision and what they are hoping to achieve. Try to get to the crux of the matter. You may well change your own view or help them to change theirs.

If you are inspired to find out more about any of the themes covered in this chapter we suggest that you start by reviewing the resources listed below.

![]()

FURTHER FOOD FOR THE CURIOUS

• Baddeley, S. and James, K. (1987) ‘Owl, fox, donkey, sheep: political skills for managers’. Management Education and Development, 18 (1). 3–19.

![]() A short, but truly inspirational, paper. The ideas presented are just as relevant today as they were at the time of publication.

A short, but truly inspirational, paper. The ideas presented are just as relevant today as they were at the time of publication.

• Chatham, R. (2015) The Art of IT Management. Swindon: BCS.

![]() Contains a lot of practical tools and techniques that will help you on your route to ‘dolphinism’. It also covers underpinning competencies such as coaching skills and developing your emotional intelligence.

Contains a lot of practical tools and techniques that will help you on your route to ‘dolphinism’. It also covers underpinning competencies such as coaching skills and developing your emotional intelligence.

1 Baddeley, S. and James, K. (1987) ‘Owl, fox, donkey, sheep: political skills for managers’. Management Education and Development, 18 (1). 3–19.

2 The political zoo is an adaptation of the model developed by Simon Baddeley and Kim James (1987) in ‘Owl, fox, donkey, sheep: political skills for managers’. Management Education and Development, 18 (1). 3–19.