7

Practical completion, completion and post-completion

Practical completion

7.1 The decision to certify practical completion is one of the most important that the contract administrator makes during the whole project as it triggers many contractual consequences that are important to both the client and the contractor. The period leading up to practical completion can be difficult and stressful. Sometimes this may be due to an (erroneous) belief by the contractor that the word ‘practical’ indicates that something that is 90 per cent finished, or could be occupied, has reached practical completion. At other times there may be pressure from a client who is very anxious to occupy the building, and who may not appreciate how much work is still needed to correct what might appear to minor matters. However, in the RIBA Building Contracts (unlike many other contracts), a clear definition of practical completion is given. Clause 9.10 states:

7.2 In addition, if optional clause 23 of CBC is selected, the contractor must have provided copies of all collateral warranties/third-party rights agreements required before practical completion can be certified (cl. 23.2).

7.3 It is suggested that ‘no aspect of the Works or Section of the Works shall be outstanding’ includes aspects of quality, as well as quantity, therefore if the quality of work is unsatisfactory, practical completion as defined has not been reached. This interpretation has been supported by the courts, for example in the well-known case of H W Nevill (Sunblest) Ltd v William Press & Son Ltd. If the client nevertheless wishes to occupy the building with minor work outstanding, then a special arrangement will need to be made, as discussed below (see para. 7.9).

H W Nevill (Sunblest) Ltd v William Press & Son Ltd (1981) 20 BLR 78

Here William Press entered into a contract with Sunblest to carry out foundations, groundworks and drainage for a new bakery on a JCT63 contract. A practical completion certificate was issued, and new contractors commenced a separate contract to construct the bakery. A certificate of making good defects and a final certificate were then issued for the first contract, following which it was discovered that the drains and the hardstanding were defective. William Press returned to the site and remedied the defects, but the second contract was delayed by four weeks and Sunblest suffered losses as a result. It commenced proceedings, claiming that William Press was in breach of contract and in its defence William Press argued that the plaintiff was precluded from bringing the claim by the conclusive effect of the final certificate. Judge Newey decided that the final certificate did not act as a bar to claims for consequential loss. In reaching this decision he considered the meaning and effect of the certificate of practical completion and stated (at page 87): ‘I think that the word “practically” in clause 15(1) gave the architect a discretion to certify that William Press had fulfilled its obligation under clause 21(1) where very minor de-minimis work had not been carried out, but that if there were any patent defects in what William Press had done then the architect could not have issued a certificate of practical completion.’

7.4 It is open to the parties to set out their own particular requirements for practical completion, including the standard expected and the means for establishing if it has been reached (cl. 9.10.1). The parties might consider, for example, requiring that mechanical services are properly commissioned, that any performance in use criteria are tested and checked (e.g. airtightness and acoustic requirements), that an operations manual is handed over and the client trained in operation of the building. Any of these would, of course, have to have been made clear in the tender documents.

7.5 The contractor is required to notify the contract administrator when it thinks that practical completion of the works, or a section, has been achieved (cl. 9.11). If the contract administrator agrees, it will issue a certificate of practical completion of the works or section as appropriate (cl. 9.11.1).

7.6 If the contract administrator does not agree, unlike in the 2014 edition, there is no requirement to inform the contractor of this. Although it may nevertheless be sensible to let the contractor know that one or more of the conditions in clause 9.10 has not yet been met, it is important to note that the contract administrator is not required to give reasons for this decision, and there is certainly no obligation to produce a ‘snagging list’. It is common practice for the contract administrator to issue such a list but, unless it has entered into special terms of appointment with the client, there is no need for it to do so. Not only is it very time-consuming and resource-hungry, it is effectively taking on the contractor’s quality assurance duties, which could ultimately lead to a confusion as to roles and responsibilities. If the contract administrator is concerned about particular defects, there is no harm in informing the contractor, provided it is made clear that these are just examples of some of the shortfalls on the project and that they are not intended to be a comprehensive list.

Consequences of practical completion

7.7 The consequences of practical completion are as follows:

- half the withheld retention is released (cl. 9.11.2);

- liquidated damages will cease (cl. 10.1);

- the defects fixing period commences (cl. 10.2);

- the contractor remedies defects notified during the defects fixing period (cl. 10.3).

7.8 These consequences are important and therefore the contract administrator should take great care to ensure the defined level of completeness has been reached before certifying practical completion. Issuing the certificate with work outstanding places considerable additional risk on the client: the key areas being that there is no longer the sanction of liquidated damages to encourage the contractor to finish promptly, and the client holds only half the retention sum as security against any hidden defects. In addition, matters such as insurance of the works and health and safety will need to be resolved, and there are practical issues to do with managing the programming and payment for the outstanding work. The contracts have no provisions to cover these aspects as they assume that the work will be finished, with the exception of defects that appear during the defects fixing period.

Use/occupation before practical completion

7.9 If the works have not reached practical completion, but the client wishes to use them, the contracts contain a provision that may be of help to the client. This allows the client to request to ‘take over’ any part or parts of the works or a section of the works before the contract administrator certifies practical completion (cl. 9.12). The contractor must grant permission, but only if the use does not interfere with the carrying out of the works. Practical completion is not certified, but the contract administrator must issue a notice ‘clearly identifying the part(s) taken over and the date of takeover, as well as any outstanding work and arrangements for access by the Contractor’ (cl. 9.13.1).

7.10 In addition, the following consequences apply:

- 9.13.2 Practical Completion will be deemed to have taken place on the date of takeover for the relevant part(s)

- 9.13.3 the Defects Fixing Period for that part(s) shall start from that date

- 9.13.4 in respect of the Contract Price for that part of the Works, the Contractor is entitled to half the amount currently retained in accordance with clause 7.15.

The contract does not specifically state what will happen to the liquidated damages payable, if the completion date is not met for the remainder of the works. In view of clause 9.13.2, the likely intention was that these would be reduced, and the normal method is to do this in proportion to the value of the work taken into over. However it would be sensible to agree this prior to the part being occupied.

7.11 There can be situations where the client is anxious to occupy part or possibly the whole of the works before any parts are sufficiently complete to be taken over under clause 9.12. Rather than viewing the work as having reached practical completion when it has not, it would be better if the parties make an ad hoc agreement as to what the arrangement will be. A suggestion was put forward in the ‘Practice’ section of the RIBA Journal (February 1992), which has frequently proved useful in practice: in return for being allowed to occupy the premises, the client agrees not to claim liquidated damages during the period of occupation. Practical completion obviously cannot be certified, and the defects fixing period will not commence, nor will there be any release of retention money, until the work is complete. Health and safety will need to be given careful consideration, and matters of insuring the works will need to be settled with the insurers.

7.12 Because such an arrangement would be outside the terms of the contract, it should be covered by a properly drafted agreement that is signed by both parties. (The cases of Skanska v Anglo-Amsterdam Corporation and Impresa Castelli SpA v Cola Holdings Ltd illustrate the importance of drafting a clear agreement.) It may also be sensible to agree that, in the event that the contractor still fails to achieve practical completion by the end of an agreed period, liquidated damages would begin to run again, possibly at a reduced rate. In most circumstances this arrangement would be of benefit to both parties, and is certainly preferable to issuing a heavily qualified takeover notice, or a certificate of practical completion, listing numerous incomplete items of work.

Skanska Construction (Regions) Ltd v Anglo-Amsterdam Corporation Ltd (2002) 84 Con LR 100

Anglo-Amsterdam Corporation (AA) engaged Skanksa Construction (Skanska) to construct a purpose-built office facility under a JCT81 With Contractor’s Design form of contract. Clause 16 had been amended to state that practical completion would not be certified unless the certifier was satisfied that any unfinished works were ‘very minimal and of a minor nature and not fundamental to the beneficial occupation of the building’. Clause 17 of the form stated that practical completion would be deemed to have occurred on the date that the employer took possession of ‘any part or parts of the Works’. AA wrote to Skanska confirming that the proposed tenant for the building would commence fitting out works on the completion date. However, the air-conditioning system was not functioning and Skanska had failed to produce operating and maintenance manuals. Following this date the tenant took over responsibility for security and insurance, and Skanska was allowed access to complete outstanding work. AA alleged that Skanska was late in the completion of the works and applied liquidated damages at the rate of £20,000 per week for a period of approximately nine weeks. Skanska argued that the building had achieved practical completion on time or that, alternatively, partial possession of the works had taken place and that, consequently, its liability to pay liquidated damages had ceased under clause 17.

The case went to arbitration and Skanska appealed. The court was unhappy with the decision and found that clause 17.1 could also operate when possession had been taken of all parts of the works and was not limited to possession of only part or some parts of the works. Accordingly, it found that partial possession of the entirety of the works had, in fact, been taken some two months earlier than the date of practical completion, when AA agreed to the tenant commencing fit-out works. Consequently, even though significant works remained outstanding, Skanska was entitled to repayment of the liquidated damages that had already been deducted by AA.

Impresa Castelli SpA v Cola Holdings Ltd (2002) CLJ 45

Impresa agreed to build a large four-star hotel for Cola Holdings Ltd (Cola), using the JCT Standard Form of Building Contract With Contractor’s Design, 1981 edition. The contract provided that the works would be completed within 19 months from the date of possession. As the work progressed, it became clear that the completion date of February 1999 was not going to be met, and the parties agreed a new date for completion in May 1999 (with the bedrooms being made available to Cola in March) and a new liquidated damages provision of £10,000 per day, as opposed to the original rate of £5000. Once the agreement was in place, further difficulties with progress were encountered, which meant that the May 1999 completion date was also unachievable. The parties entered into a second variation agreement, which recorded that access for Cola would be allowed to parts of the hotel to enable it to be fully operational by September 1999, despite certain works not being complete (including the air conditioning). In September 1999, parts of the hotel were handed over, but Cola claimed that such parts were not properly completed. A third variation agreement was put in place with a new date for practical completion and for the imposition of liquidated damages. Disputes arose and, among other matters, Cola claimed for an entitlement for liquidated damages. Impresa argued that it had achieved partial possession of the greater part of the works, therefore a reduced rate of liquidated damages per day was due. The court found that, although each variation agreement could have used the words ‘partial possession’, they had in fact instead used the word ‘access’. The court had to consider whether partial possession had occurred under clause 17.1 of the contract, which provides for deemed practical completion when partial possession is taken, or whether Cola’s presence was merely ‘use or occupation’ under clause 23.3.2 of the contract. The court could find nothing in the variation agreements to suggest that partial possession had occurred. It therefore ruled that what had occurred related to use and occupation, as referred to in clause 23.3.2 of the contract, and that the agreed liquidated damages provision was therefore enforceable.

Non-completion

7.13 If the contractor fails to achieve practical completion of the works by the date for completion, the client may deduct liquidated damages at the agreed rate (cl. 10.1). There is no need for the contract administrator to have issued any non-completion certificate, although it would normally write to the client advising it of the position.

The defects fixing period

7.14 The contractor is required to ‘remedy all defects associated with the Works notified to them during the Defects Fixing Period’ (cl. 10.3). The period begins at practical completion and lasts for the length of time entered in the Contract Details (cl. 10.2, item M). The notes to item M indicate that the minimum period is 3 months, however, 12 months (12 months is commonly used so that any mechanical services such as heating systems can be run through four seasons). A shorter period might be acceptable for very small projects.

7.15 It is suggested that although clause 10.3 suggests that the contractor is only obliged to correct notified defects, the obligation is wider than this. As part of its general duty to complete the works satisfactorily, the contractor would be obliged to ascertain whether any defects have appeared, and to correct any work that was defective. The notification process allows for the architect to raise matters of concern, and for arrangements to be made for access that suit all parties, but if the contractor is aware of any matters not notified it should alert the contract administrator so that they can be dealt with. There is no express requirement for the contract administrator to prepare a schedule of defects at the end of the defects fixing period, as there is in some of the other standard contracts (e.g. IC16, cl. 2.30). However, the contract administrator is required to issue a notice to the contractor requiring it to remedy any defect which it fails to fix (cl. 10.5). If the contractor does not comply with the notice promptly, the client may engage others to rectify the problem, and all costs are the responsibility of the contractor (cl. 10.6). This right would only arise if the correct procedures are followed; if the client, for example, refuses to allow the contractor reasonable access for inspecting and undertaking work, this might result in the client being unable to claim the costs of remedying the defects by others (Pearce and High Ltd v John P Baxter and Mrs A S Baxter).

Pearce and High Ltd v John P Baxter and Mrs A S Baxter [1999] BLR 101 (CA)

The Baxters employed Pearce and High on MW80 to carry out certain works at their home in Farringdon. Following practical completion, the architect issued interim certificate no. 5, which the employer did not pay. The contractor commenced proceedings in Oxford County Court, claiming payment of that certificate and additional sums. The employer in its defence and counterclaim relied on various defects in the work that had been carried out. Although the defects liability period had by that time expired, neither the architect nor the employer had notified the contractor of the defects. The Recorder held that clause 2.5 was a condition precedent to the recovery of damages by the employer, and further stated that it was a condition precedent that the building owner had notified the contractor of patent defects within the defects liability period. The employer appealed and the appeal was allowed. Lord Justice Evans stated that there were no clear express provisions within the contract which prevented the employer bringing a claim for defective work, regardless of whether notification had been given. He went on to state, however, that the contractor would not be liable for the full cost to the employer of remedying the defects, if the contractor had been effectively denied the right to return and remedy the defects itself.

7.16 In practice, correction of defects is normally left until the end of the defects fixing period, as it is usually more convenient for both parties if all the work is done together. However, sometimes a defect can cause considerable problems to the client, in which case the contractor should take steps as soon as it is aware of the matter. In either case, if the contractor fails to deal with any defect satisfactorily, the contract administrator should issue a clause 10.5 notice, in order to trigger the client’s right to engage others if necessary. After the end of the defects fixing period, when the contract administrator is satisfied that all defects are remedied, the contract administrator is required to notify the parties accordingly (cl. 10.4).

Payments following practical completion

7.17 Following practical completion, in the absence of any limiting provision it appears as if the payment dates, and therefore certification, continue at monthly intervals (cl. 7.1). With respect to milestone payments, or the single payment on practical completion, as clause 18.1 states that ‘the part of item K of the Contract Details regarding payment certificate frequency shall not apply’, there would be no further certificates until the final payment, unless the parties agree otherwise.

Final contract price and payment

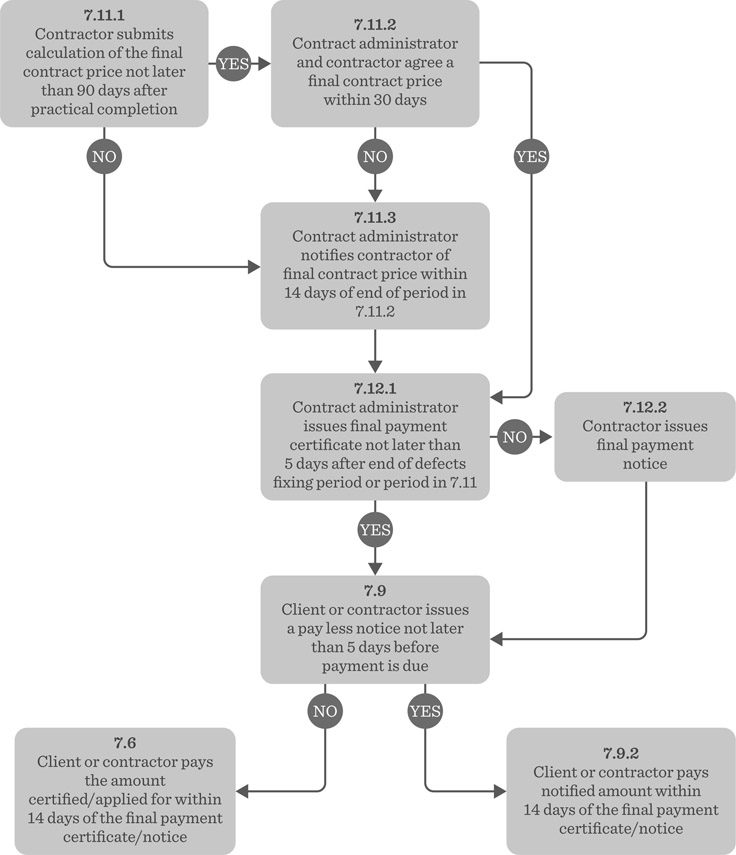

7.18 Most contracts contain provisions for dealing with the final assessment of the contract price. Clause 7.11.1 requires the contractor to submit its calculation, along with the relevant supporting documentation, to the contract administrator within 90 days of practical completion (note that in the 2014 version the equivalent clause stated within 90 days of the defects fixing period, which must have been an error).

7.19 The contract then requires the contract administrator and the contractor to endeavour to reach agreement on the final amount within 30 days of the submission (cl. 7.11.2). If they are unable to reach agreement, or the contractor fails to submit a calculation, the contract administrator is required to calculate the ‘final Contract Price’ and notify it to the contractor not later than ‘14 days after the 30 day period referred to in clause 7.11.2’ (cl. 7.11.3).

Figure 7.1 Final certificate

7.20 The final contract price is said to be ‘subject to resolution of any defects arising during the Defects Fixing Period’ (cl. 7.11.4). The contract does not explain what this means but, considered in practical terms, at the time the notification is given the full extent of defects may not be known. The time limits are well within the defects fixing period – in fact, there is nothing to prevent the contractor submitting its assessment immediately after practical completion, in which case either agreement will be reached within 30 days or a notification must be sent within a further 14 days – just six weeks into a defects fixing period that could last six months or a year – at a point when work that appears to be sound may contain many latent defects. Any amount agreed or notified, even if referred to as the final contract price, cannot be binding, but must be based on the assumption that work that appears to be compliant is in fact complaint, and adjusted following the end of the defects fixing period. The contract does not explain how that adjustment would be assessed, but if no agreement is reached, the contract administer should issue a revised notification of the final contract price promptly.

7.21 Clause 7.12 states: ‘No later than 5 days after the end of the Defects Fixing Period or, where applicable, the period set out in clause 7.11, whichever is the later … the Architect/Contract Administrator shall issue a final Payment Certificate (see Figure 7.1) which complies with the requirements of clause 7.5 representing the amount due for final payment’ (cl. 7.12.1). If the contract administrator fails to issue the certificate, the contractor may issue a final payment notice (cl. 7.12.2). The certificate or payment notice should be calculated on the same basis as that for interim payments.

7.22 The client or contractor is required to pay the amount shown on the final payment certificate or notice. The ‘payment due date’ is the date of the certificate or notice, whichever is applicable (cl. 7.13) and, under clause 7.7, the final date for payment will be 14 days from the due date. The requirement to pay is, as with interim certificates, subject to the right to issue a pay less notice

Conclusiveness

7.23 Unlike in other contracts, it should be noted that no payment certificates are stated to be conclusive evidence that any matters or duties under the contract have been finally discharged, which means that even after the final payment certificate is issued, it is possible for either party to raise a claim for breach of contract. Having said that, it should be noted that if a matter is raised that could have been raised under the currency of the contract, and there is no good reason why the contractual mechanisms were not used to resolve it at that time, then it is unlikely that the claim would be successful.