1

Introduction

1.1 In November 2014 the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) launched two new building contracts: The RIBA Concise Building Contract 2014 and the RIBA Domestic Building Contract 2014. These are not the first contracts to be published by the RIBA. In fact, the very first UK standard form of building contract was published by the RIBA jointly with the Institute of Builders and the National Federation of Building Trades Employers of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in 1902 (and cost one shilling!). In 1931 the Joint Contracts Tribunal (JCT) was formed, and the drafting and publishing of the contract became a pan-industry project. It continued to be called the RIBA Standard Conditions of Contract until 1963, when it was republished as the JCT Standard Form of Building Contract.

1.2 The JCT now publishes an extensive suite of contracts. However, the RIBA identified a need, through feedback from its members, for short, easy-to-read and flexible contracts that would be suitable for less straightforward projects than those catered for by the JCT Home Owner contracts and that could be used on domestic and commercial works. It has therefore published two new forms, designed for use in conjunction with RIBA’s architect/consultant appointment agreements, the RIBA Domestic Project Agreement 2010 (2012 revision) and the RIBA Concise Agreement 2010 (2012 revision).1

Features of the RIBA Building Contracts

1.3 According to its guidance notes, the RIBA Concise Building Contract 2014 (CBC) is intended for use on ‘all types of simple commercial building work’. It can be used in both the private and public sectors, as it incudes optional provisions dealing with official secrets, transparency, discrimination and bribery as normally required by public sector clients (item BB and clause A9). The RIBA Domestic Building Contract 2014 (DBC), as its name suggests, is intended for domestic work, including renovations, extensions, maintenance and new buildings. Its guidance notes state that this is limited to ‘work done to the Customer’s home’, i.e. to contracts that fall under the ‘residential occupier exception’ in the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996, as amended by Part 8 of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009 (hereafter referred to as the Housing Grants Act) (see para. 1.14). DBC is endorsed by the HomeOwners Alliance.

1.4 Both contracts are available in hard copy and electronic formats, and can be purchased from: www.ribacontracts.com.

1.5 Key features of the RIBA Building Contracts are:

- collaboration provisions: advance warnings, joint resolution of delay, proposals for improvements and costs savings;

- management provisions: pre-start meeting (both contracts), progress meetings (CBC only);

- flexible payment options;

- provision for contractor design, with a ‘fit for purpose’ liability option;

- optional provisions for a contractor programme, with penalties for non-provision;

- optional provisions for client-selected suppliers and subcontractors;

- mechanisms for dealing with changes to the project which allow for agreement and include specified timescales;

- option for commencement and completion in stages;

- terms compliant with the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999 for consumer clients;

- guidance notes on use and completion are included.

1.6 All of these features are discussed at various points throughout this Guide.

Suitability for different procurement routes

1.7 Both of the RIBA Building Contracts are suitable for projects that are procured on what is normally referred to as a ‘traditional’ procurement route, i.e. one where the client engages at least one, and possibly several, firms of consultants to prepare a design and complete full technical documentation before the project is tendered to contractors. With traditional procurement, it is common that some parts of the design are completed by the contractor or by specialist subcontractors (this version is sometimes referred to as ‘traditional plus contractor design’). The RIBA Building Contracts would be suitable in this situation, with either the main contractor or a subcontractor (client selected, if required) undertaking the design. Traditional procurement is widely used – it was applied in around 76 per cent of projects undertaken in the UK in 2010, which accounted for 41 per cent of the total value (RICS and Davis Langdon, 2012).

1.8 The RIBA Building Contracts are not intended for use in design and build procurement, i.e. where the contractor is responsible for both the design and the construction of the project. It would be possible to adapt them for this use, but there would still be a need for a contract document giving full details of the design requirements, and for an appointed contract administrator (not usual in design and build contracts). In addition, all the provisions relating to design would require amendment, and more detailed provisions regarding submission and approval of the developing design would have to be added.

1.9 The contracts are also not intended to be used with management contracting or construction management arrangements (where the project is tendered as a series of packages to separate firms, with work progressing on a rolling programme basis after the first package is let). Management procurement arrangements are normally used on very large projects; however, on a smaller scale, clients who wish to manage projects themselves sometimes adopt a similar system and engage a number of separate companies (often referred to as ‘separate trades’). The RIBA Building Contracts might be suitable for some of the larger work packages, but thought should be given as to how all the separate contracts are to be co-ordinated. This is not an easy task, and the apparent savings achieved by cutting out the main contractor’s markup may be more than offset by the amount of time the client has to spend managing the process, or by the additional fees charged by consultants if they undertake this role.

1.10 However, within the traditional plus contractor design route, the RIBA Building Contracts would be suitable for a wide range of projects, from very small-scale alterations and refurbishment works, to moderately sized projects relating to existing or new buildings. As mentioned above, CBC’s guidance notes refer to ‘simple’ work, and generally it is the level of complexity, rather than the value, that should be the key determinant in the choice of contract.

1.11 Although the RIBA Building Contracts have many useful features (see para. 1.5), which mean they are flexible, some of the provisions lack the detail to be found in larger contracts. Examples are those relating to design submission and approval procedures and insurance clauses. Other provisions commonly found in larger contracts are not included, such as fluctuations clauses and contractor bonds – if these are required then other standard contracts should be considered.

Differences between the concise and domestic contracts

1.12 The key difference between the two contracts is that, as noted above, CBC complies with the Housing Grants Act, whereas DBC does not. This results in significant differences in the payment and dispute resolution terms (see paras. 1.14–1.19). In addition, each version contains some features that are not included in the other.

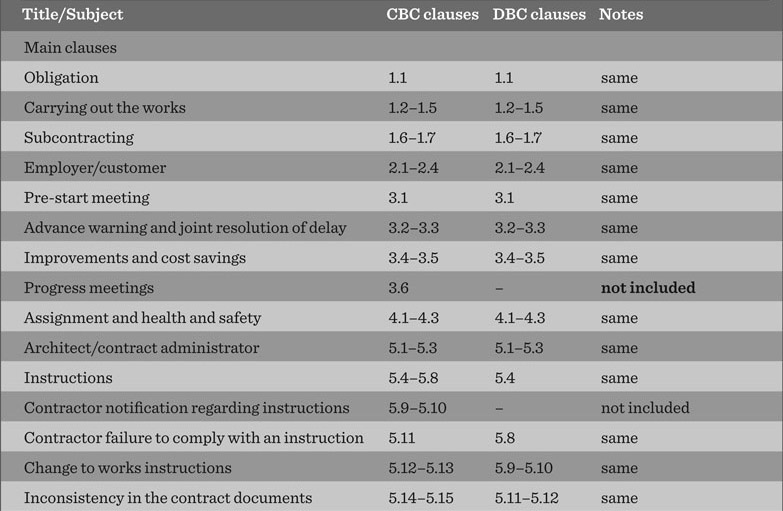

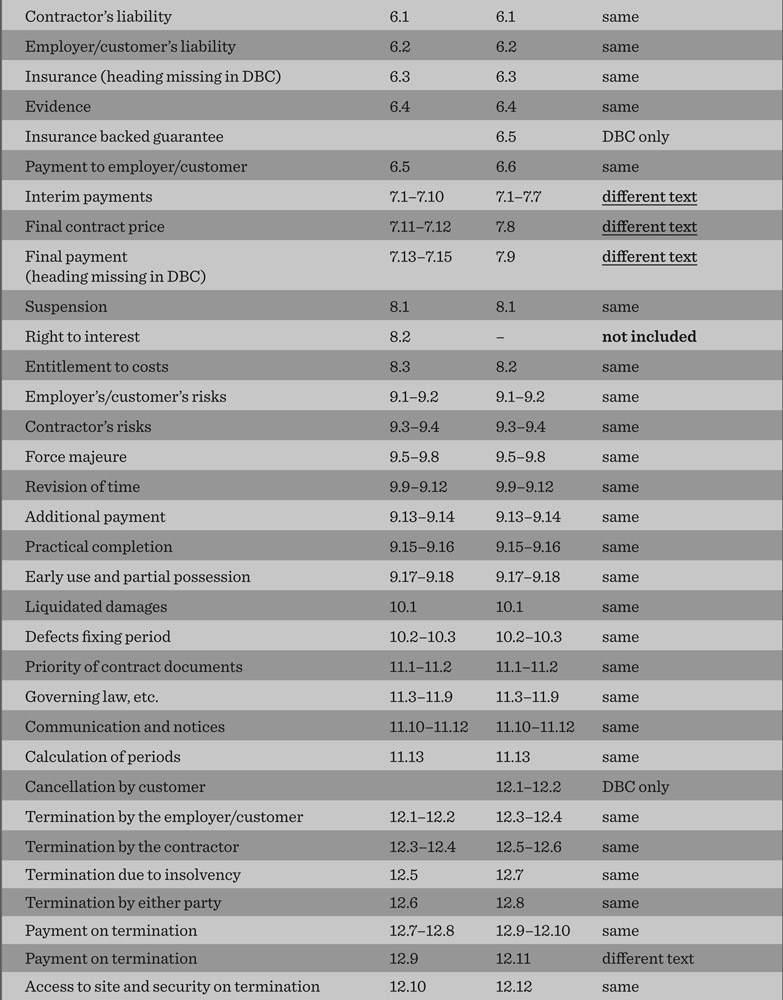

1.13 A full comparison of the differences between the two versions is set out in Table 1.1. The key differences in this list are set in bold, with those relating to the Housing Grants Act underlined.

Compliance with the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (as amended)

1.14 The Housing Grants Act applies to most construction contracts.2 It requires that construction contracts include specific terms relating to adjudication and payment:

- the right to stage payments;

- the right to notice of the amount to be paid;

- the right to suspend work for non-payment;

- the right to take any dispute arising out of the contract to adjudication.

1.15 If the parties fail to include these provisions in their contract, the Act will imply terms to provide these rights (section 114) by means of the Scheme for Construction Contracts (England and Wales) Regulations 1998.

1.16 However, there is an important exception; it does not apply to projects where one of the parties is a ‘residential occupier’. The residential occupier exception applies to projects for which the primary purpose is beneficial use by the client as a residence (section 106). This would include buildings that the client is occupying or intending to occupy as its main residence, and might also include a second home if the client is the main user and there is no intention to use it as a holiday let (Westfields v Lewis). However, work to buildings in the grounds of a residence that will not be lived in by the customer, or work to divide a property into flats where only one flat will be retained by the customer, will not fall under the exception. Similarly, work on other residential properties, for example for landlords, local authorities or housing associations, will usually be covered by the Act.

1.17 CBC 2014 contains provisions that comply with the Housing Grants Act and can therefore be used on any project, including those to which the Act applies, whereas DBC 2014 can only be used for ‘residential occupier’ projects.

1.18 The effect of this is that the payment terms differ considerably between the concise and the domestic versions. In brief, CBC sets up ‘Due Dates’, allows the contractor to apply for payment not later than ten days before each due date, requires the contract administrator to certify payment within five days of the due date, and requires the employer to pay within 14 days after the due date. If the employer wishes to pay less than the amount certified, it must issue a ‘Pay Less Notice’ not later than five days before the final date for payment. In DBC, however, the procedure is much simpler; there are no due dates, the contract administrator issues certificates at monthly intervals, the contractor then issues an invoice to the customer, and the customer pays with 14 days of receipt of the invoice. If the customer decides to make a deduction, it explains the reason for the deduction at the time of making the payment (these provisions are explained in full in Chapter 6).

1.19 As CBC’s additional terms introduce considerable complications, it would be unwise to use CBC on projects with a residential occupier, who may find the provisions onerous; the guidance notes emphasise that it ‘is not suitable for non-commercial work’. As well as the practicality of operating the provisions, there is also a risk that some of the terms may be caught by the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999 if not individually negotiated with the client prior to entering into the contract (see para. 1.25).

Other differences between the contracts

1.20 Compliance with the Housing Grants Act is obviously a key difference between the contracts, however there are other important differences. For example, DBC has an option whereby the customer may elect to act as contract administrator (cl A6). It also allows for the customer to require an insurance backed guarantee covering the contract price (cl 6.5), or a new building warranty (cl A7, see para. 2.21). Although insurance backed guarantees are normally used in domestic projects, they can be provided for commercial work. If an employer using the CBC requires one, a new clause will need to be introduced to the contract.

1.21 There are also several provisions in CBC that are not included in DBC, such as the requirements to hold progress meetings and for the contractor to submit an updated programme in advance of the meeting. This omission seems a great pity, as both features, particularly the regular programme updates, are useful on any type of project. It may be that the drafters felt this would overcomplicate a domestic project, but as such projects can be significant in size and complexity, and as these features are not to be found in JCT contracts, it may be an opportunity lost.

1.22 CBC includes optional clauses that provide for advance payment, for the employer to provide evidence of ability to pay the contract price, and for the right to interest on unpaid amounts. These are also omitted from DBC, which seems logical in a domestic context (especially the latter, as the Late Payment of Commercial Debts (Interest) Act 1998 would not apply to domestic contracts). CBC also includes an optional clause dealing with collateral warranties and third party rights (see para. 2.28). These are usually provided to future purchasers or tenants, or to funders. DBC does not provide for collateral warranties as such warranties do not normally arise in a domestic context. In the unlikely event that the customer’s bank requires a warranty, then an additional provision would need to be introduced.

Use of CBC by a ‘consumer’

1.23 The law affords special protection to persons who enter into a contract as a ‘consumer’, through what is referred to collectively as consumer protection legislation.

1.24 It is important to note that the definitions of ‘residential occupier’ and ‘consumer’ are not the same. The usual definition of consumer in relevant legislation is a person who is acting ‘for purposes which are outside his trade, business or profession’. This could include, for example, a wealthy business tycoon who is developing a country estate with several large residences for members of his family; in other words, it is not confined to small projects, or to those undertaking work on their own home, or to residential occupiers. Therefore, although a residential occupier will always be a consumer (i.e. the customer in DBC will be a consumer), there may also be situations where a consumer is not a residential occupier, in which case CBC would be the appropriate choice.

1.25 A key piece of legislation affecting consumers is the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999. Essentially, these provide that terms that significantly affect the balance of rights between the parties, and which are not individually negotiated, may be deemed unfair and therefore void.

Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999

These Regulations only apply to terms in contracts between a seller of goods or supplier of goods and services and a consumer, and only where the terms have not been individually negotiated (this would generally include all standard contracts). A consumer is defined as a person who, in making a contract, is acting ‘for purposes which are outside his trade, business or profession’ (section 3(1)). An ‘unfair term’ is any term that causes a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights to the detriment of the consumer, and the regulations state that any such term will not be binding on the consumer. An indicative list of terms is given in Schedule 2 to the regulations and includes, for example, any term ‘excluding or hindering the consumer’s right to take legal action or exercise any other legal remedy, particularly by requiring the consumer to take disputes exclusively to arbitration’.

1.26 Both of the RIBA Building Contracts have been drafted with the intention that they should be fair. The language is certainly clear and should be relatively easy for a lay client to understand. Nevertheless, it is always wise for an architect advising a customer on procurement matters to go through the terms with any client, ideally before the project is sent out to tender, and certainly before the tender is accepted and the contract formed. They should also ensure that all terms are explained carefully to ‘consumer’ clients, in order that they can be considered to have been individually negotiated. It is important, for example, that if the arbitration option is selected, or if any other amendments are made which could be seen as limiting the client’s rights, these have been explained and discussed. It would also be important that, where CBC is being used with a consumer, the payment provisions are explained, as some of these provisions may be considered onerous.

1.27 Similarly, DBC includes the right of the customer to cancel the contract within 14 days of signing it (cl 12.1), something required by the Consumer Contracts (Information, Cancellation and Additional Charges) Regulations 2013. This right is not included in CBC. Where CBC is being used with a consumer, it might be wise to add this provision, or to make it clear that the employer would have this right in any event under the Regulations.

1.28 Finally, those dealing with consumers should look out for an important change in consumer protection legislation: the Consumer Rights Act 2015 has recently been passed by Parliament, although at the time of writing, the date of coming into force is not yet known. It will replace much of the existing law on consumer protection.

Consumer Rights Act 2015

The Act aims to summarise in one place the obligations of traders in relation to consumers for most types of contract, together with consumers’ rights against traders. It includes provisions covering unfair terms that are similar to those discussed above. It also includes additional protection for the consumer. A key clause in the Act is as follows:

The key point to note is that the consumer may rely on anything spoken or written to it as if it were a term of the contract, which would include any statements made about the cost, timescale, accommodation, specification and performance of a finished building or the services to be provided. This would mean that any additional undertakings given by the contractor, for example during the tender period, would effectively become part of the contract between the parties. Other provisions in the Act that are of relevance are the right to a price reduction (section 56) or to require repeat performance (section 55) if the consumer is unhappy with the work that has been carried out.

Comparison with other contracts

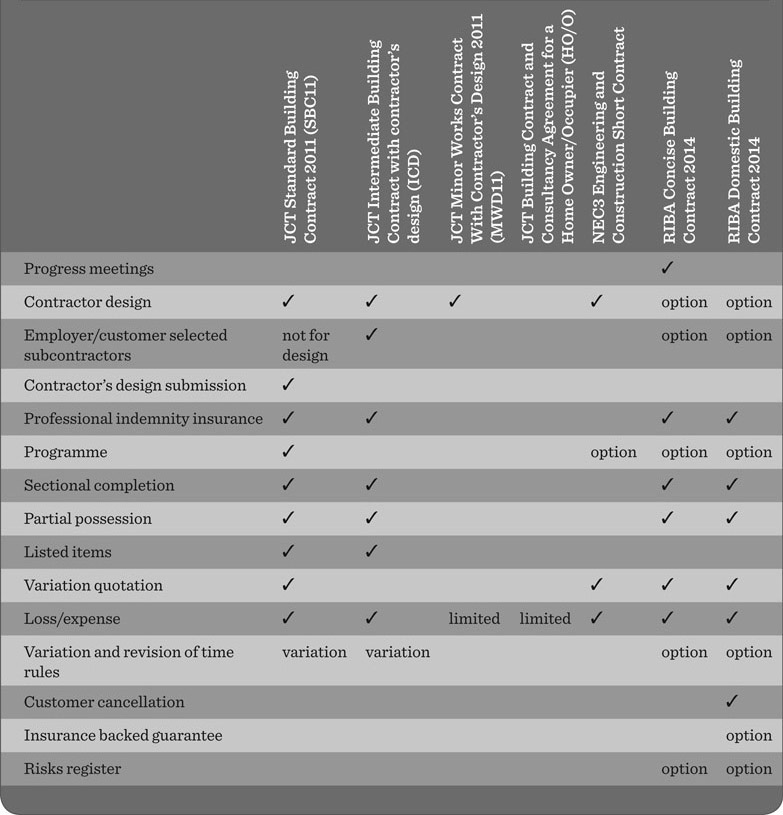

1.29 The RIBA Building Contracts are significantly different to others that are currently available. One obvious feature is their length; they are shorter than most other contracts available for the intended scale of work, with the exception of the JCT Home Owner contracts (HO/O), and possibly the NEC3 Engineering and Construction Short Contract (NEC3) (with which they are comparable in length). However, they offer considerably more features, including a large number of optional clauses, than are available in competing contracts (the NEC3 Short Contract does not have the optional clauses that are contained in the full version). In fact, the RIBA contracts even offer some features that are not available in much larger contracts, as can be seen in Table 1.2.

1.30 In summary, the new RIBA Building Contracts offer attractive alternatives to existing contracts in that they are relatively short and easy to read, and yet contain a range of innovative features not found in other contracts. This will make them appealing both to architects and their clients and to contractors.

1.31 One of the drawbacks of new contracts is that, unlike longstanding ones, they are not tried and tested. Their practical application has not been put to the test, and the exact meanings of clauses have not been established in the courts. Some assurances can, however, be given regarding the RIBA Building Contracts. Drafts of the contracts were subject to extensive comments by potential users, by experts and by lawyers, and the contracts are written in plain English so that the intended meaning is generally clear. It is possible in some instances to use analogy with equivalent clauses in other contracts, where the meaning and effect have been discussed in court cases, as a means of interpreting the provisions of the new contracts. A comparative method has therefore been used throughout this Guide, both as a means of explaining key provisions to readers who might be more familiar with other contracts, and to justify comments and interpretation of various provisions.