Now What?

by Joan C. Williams and Suzanne Lebsock

FAREWELL TO THE WORLD where men can treat the workplace like a frat house or a pornography shoot. Since Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein was accused of sexual misconduct in early October, similar allegations have been made about nearly 100 other powerful people. They all are names you probably recognize, in fields including media, technology, hospitality, politics, and entertainment. It’s a watershed moment for workplace equality and safety; 87% of Americans now favor zero tolerance of sexual harassment.

Not only is this better for women, but it’s better for most men. A workplace culture in which sexual harassment is rampant is often one that also shames men who refuse to participate. These men-who-don’t-fit, like the mistreated women, face choices about whether and how to intervene without endangering their careers.

Still, it’s unnerving for many men to see the numbers of those toppled by accusations grow ever higher. The recent summary dismissals of high-powered executives and celebrities have triggered worries that any man might be accused and ruined. Half of men (49%) say the recent furor has made them think again about their own behavior around women. Men wonder whether yesterday’s sophomoric idiocy is today’s career wrecker.

This is not a fight between men and women, however. One of the journalists to break the Weinstein story was Ronan Farrow, son of Mia Farrow and Woody Allen. Yes, that Woody Allen—the one who married his longtime girlfriend’s daughter and is alleged to have sexually abused another daughter. “Sexual assault was an issue that had touched my family,” said Farrow, who noted that this experience was instrumental in driving his reporting.

To repeat: This is not a fight between men and women. It’s a fight over whether a small subgroup of predatory men should be allowed to interfere with people’s ability to show up and do what they signed up for: work.

Several changes in the past decade have brought us to this startling moment. Some were technological: The internet enables women to go public with accusations, bypassing the gatekeepers who traditionally buried their stories. Other changes were cultural: A centuries-old stereotype—the Vengeful Lying Slut—was drained of its power by feminists who coined the term “slut shaming” and reverse-shamed those who did it. Just as important, women have made enough inroads into positions of power in the press, corporations, Congress, and Hollywood that they no longer have to play along with the boys’ club; instead they can, say, lead the charge to force Al Franken’s resignation or break the story on Harvey Weinstein.

The result of all these changes is what social scientists call a norms cascade: a series of long-term trends that produce a sudden shift in social mores. There’s no going back. The work environment now is much different from what it was a year ago. To put things plainly, if you sexually harass or assault a colleague, employee, boss, or business contact today, your job will be at risk.

How the #MeToo Movement Changes Work

As commonplace as these dismissals have come to seem, we know that we are only beginning to scratch the surface of the harassment culture. In “You Can’t Change What You Can’t See: Interrupting Racial & Gender Bias in the Legal Profession,” a forthcoming study of lawyers conducted by the Center for WorkLife Law (which Joan directs) for the American Bar Association, researchers found sexual harassment to be pervasive. Eighty-two percent of women and 74% of men reported hearing sexist comments at work. Twenty-eight percent of women and 8% of men reported unwanted sexual or romantic attention or touching at work. Seven percent of women and less than 1% of men reported being bribed or threatened with workplace consequences if they did not engage in sexual behavior. Fourteen percent of women and 5% of men said that they had lost work opportunities because of sexual harassment, which was also associated with delays in promotions, reduced access to high-profile assignments and sponsorship, bias against parents, and higher intent to leave. The three most acute types of harassment (excluding sexist remarks) were associated with reductions in income, demotions, loss of clients and office space, and removal from important committees.

These patterns hold true beyond the legal profession. According to a recent study by researchers at Oklahoma State University, the University of Minnesota, and the University of Maine, women who were sexually harassed were 6.5 times as likely to change jobs as women who weren’t. “I quit, and I didn’t have a job. That’s it. I’m outta here. I’ll eat rice and live in the dark if I have to,” remarked one woman in the study.

Low-wage women, who often live paycheck to paycheck, and women who are working in the U.S. illegally are the most vulnerable. A survey of nearly 500 Chicago hotel housekeepers revealed that 49% had encountered a guest who had exposed himself. Janitors who work the graveyard shift and farmworkers have had trouble defending themselves against predatory supervisors. And restaurant workers experience it from three directions. A 2014 report aptly titled “The Glass Floor,” which shares the findings of a survey of 688 restaurant workers from 39 states, reveals that nearly 80% of the female workers had been harassed by colleagues. Nearly 80% had been harassed by customers, and 67% had been harassed by managers—52% of them on a weekly basis. Workers found customer harassment especially vexing because they were loath to lose crucial income from tips. Small wonder that almost 37% of sexual harassment complaints filed by women with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in 2011 came from the restaurant industry.

The stories finally becoming public further highlight how sexual harassment subverts women’s careers: Ashley Judd and Mira Sorvino found acting jobs harder to get after they rebuffed the voracious Weinstein. After Gretchen Carlson complained of a hostile work environment, she was assigned fewer hard-hitting interviews on Fox & Friends and, according to her legal complaint, was cut from her weekly appearances on the highly rated “Culture Warrior” segment of The O’Reilly Factor. Because word got out that Ninth Circuit judge Alex Kozinski sexually harassed clerks, many women did not apply for a clerkship at that court, which positions young lawyers to get clerkships at the U.S. Supreme Court—the biggest plum in the legal basket. When the ambitious congressional staffer Lauren Greene complained of sexual harassment by her boss, Representative Blake Farenthold, her career in politics evaporated. Today she works as a part-time assistant to a home builder.

A point often overlooked is that some sexual harassment victims are men. Men filed nearly 17% of sexual harassment complaints with the EEOC in 2016. Some men are harassed by women, but many are harassed by other men, some straight, some gay. A roustabout on an oil platform was harassed by coworkers on his eight-man crew, the U.S. Supreme Court found in 1998; the coworkers were offended by what they perceived as his insufficient machismo. Recently the Metropolitan Opera suspended longtime conductor James Levine after several men accused him of masturbation-heavy abuse that took place from the late 1960s to the 1980s, when his victims were 16 to 20 years old.

Such behavior is no longer seen as a “tsking” matter. Historically, it has been hard to win a sexual harassment suit, but rapidly shifting public perceptions may change that. Seventy-eight percent of women say they are more likely to speak out now if they are treated unfairly because of their gender. About the same percentage of men (77%) say they are now more likely to speak out if they see a woman being treated unfairly. It’s a new day for a simple reason: Women are being believed.

Everything Is Changing

The strongest indicator that we’re experiencing a norms cascade came when Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell stood up for the women—four of them at the time—who had come forward with revelations about senatorial candidate Roy Moore.

“I believe the women,” McConnell said.

The statement stands in stark contrast to Anita Hill’s treatment in 1991, when she testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee that Clarence Thomas, then a nominee to the Supreme Court, had sexually harassed her. Senators subjected her to a humiliating inquisition, watched by a rapt national television audience. Another former employee was waiting in the wings to describe how Thomas had sexually harassed her, too. But she was never called to testify. Instead, Hill withstood the all-male committee’s bullying alone. After the hearings, opposition to Hill made her life at the University of Oklahoma so difficult that she left her tenured position—an object lesson on the risks facing anyone who dared to raise a charge of sexual harassment.

A recent poll by NPR dramatizes the sudden shift: 66% of Americans think that women who reported sexual harassment were generally ignored five years ago. Only 26% think that women are ignored today. When did we begin believing the women? What changed? And what are the implications for men?

We can trace the disbelief of—or at best, disregard for—women to the old stereotype we mentioned earlier, the one that holds women to be fundamentally irrational, vengeful, deceitful, and rampantly sexual.

An ancient version of this stereotype appears in Genesis, in which Eve commits the first sin and then drags Adam and the rest of humanity down with her for all time. Through the ages in Judeo-Christian tradition, authors expounded upon feminine evil. Among the most vivid prose stylists were two German friars, who in 1486 produced the classic book of witch lore The Malleus Maleficarum (or The Hammer of Witches). “What else is woman but a foe to friendship, an unescapable punishment, a necessary evil, a natural temptation, a desirable calamity, a domestic danger, a delectable detriment, an evil of nature, painted with fair colours!” they wrote. More to the point for us, perhaps, is their claim that a woman “is a liar by nature.”

Although by the 19th century more-positive images of women arose, the stereotype of the Vengeful Lying Slut was too useful to die. It was imposed on entire classes of women, notably African-American women, as scholars have amply documented, and on working-class women pressured into sex by bosses. It was used to ostracize and humiliate high schoolers who found themselves suddenly disparaged as “easy.” Whenever men, and sometimes boys, exploited women—or often girls—the stereotype of the Vengeful Lying Slut supplied the words to justify their behavior: She wanted it/asked for it/had it coming.

The stereotype alas persists. It underlies men’s fears that they, too, will be brought down by false allegations. Some men have become so frightened that they now refuse to meet (or to eat with) a female colleague alone. When Roy Moore was accused of sexual assault, his campaign said he was the victim of a “witch hunt.” That response is a telling and time-honored way of discrediting victims.

The #MeToo and Time’s Up movements show that women can no longer be silenced by threats of slut shaming. When a manager at Google told one of the female engineers who worked there, “It’s taking all my self-control not to grab your ass right now,” she tweeted it out to the world. In the first 24 hours after actress Alyssa Milano suggested that victims of harassment reply “me too” to a tweet in October, 12 million women made #MeToo posts on Facebook. Instead of distancing themselves from those challenging sexual harassment, as might have happened in the past, actors and actresses wore black to the 2018 Golden Globes to signal their solidarity.

Translating outrage into action, however, requires moving beyond hashtags toward new norms of workplace conduct. It’s a precarious moment, and a lot could go wrong. Just think what might have happened if the Washington Post, with admirable rigor, had not uncovered the truth when a woman approached it with a dramatic but false accusation against Roy Moore. Her purpose? To snooker the Post into publishing a bogus story and to thereby cast doubt on all mainstream media reporting the claims against Moore. But so far so good, with early signs that workplaces are indeed changing.

Firing Is the New Settlement

In the past companies often quietly paid to settle sexual harassment complaints against high-powered miscreants and tried to limit the damage through nondisclosure agreements. Incidents at Fox gave rise to at least seven settlements (some against Fox, some against individuals at Fox). Weinstein reportedly paid out eight. Despite getting large payouts, the plaintiffs were the ones who were forced to leave their companies, and many suffered career interruptions.

Quiet settlements are now becoming harder to justify. The unceremonious firings and forced resignations of famous men demonstrate that companies are moving away from that strategy. Settlements will likely continue in some circumstances, such as a first offense involving mild or ambiguous behavior or a situation that is consensual but violates company standards. But long strings of settlements in egregious cases will increasingly be seen as a breach of the directors’ duty to the company. Boards of directors have never tolerated financial fraud and violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, and they are likely to adopt the same standards for harassment—firing without severance pay.

It’s important to recognize that most of the firings have occurred at companies with sophisticated legal and HR departments, on the advice of counsel and with the involvement of senior management or the board or both. We should not assume that they are disclosing all the evidence they have. Companies have a strong motive not to release such evidence, lest the former employee use it as ammunition in a defamation or wrongful discharge suit. That’s what companies do when they sack someone for cause, and that’s what they are doing here.

Some worry that people will be fired too quickly and without due process. One point that’s often overlooked: Due process isn’t required of private employers, only public ones. What people are trying to insist on, quite properly, are fair procedures that uncover the truth. Companies should follow the same procedures they use when an employee has been accused of any type of serious misconduct. Typically, the employee is placed on leave while an investigation is performed. In most cases, although not all, that’s what has been happening with sexual harassment cases.

Credibility assessments are, of course, important. Women are human beings, and sometimes human beings—male and female—lie. That’s why we need to apply the standard methods we always use to assess credibility. Those methods are flawed, but they are all we have; if they will do for every other context, they will do for sexual harassment, too.

As we enter this new era, here’s a comforting thought from someone who has spent his life thinking about how to ferret out the truth, the prominent evidence scholar Roger Park (a colleague of Joan’s). His observation about sexual harassment is this: “Men have a motive to do it and lie, whereas women don’t have a motivation to lie, considering what an ordeal it is.” Making even true allegations of sexual harassment has historically been a poor career move.

That provides some assurance that reports of harassment are truthful. So do large numbers of people with similar stories. At least 42 women have come forward with allegations against Weinstein, and at least 10 against Ken Friedman, the New York restaurateur. At least a dozen people have made accusations against Kevin Spacey. Those numbers lend credibility to the allegations.

Employers who want to set up processes for handling harassment can begin with the standard sexual harassment policies. The Society for Human Resources has one; others are free online. Organizational training should spell out what’s acceptable, which will vary from company to company. Some companies may want to add detail in light of recent events. Surprising as it sounds, some people seem to need a heads-up that porn, kissing, back rubs, and nudity are not appropriate at work.

How can this be? Here’s a clue. At a dinner Judge Kozinski held with law clerks, he steered the conversation to the “voluptuous” breasts of a topless woman in a film, according to someone present. When one woman at the dinner reacted negatively, Kozinski responded that, well, he was a man.

Some men have an urgent need to preserve sexual harassment as a prerogative because, they feel, their manliness is at stake. But theirs is just one definition of manliness—a toxic and outdated one. It’s time to move on.

The Workplace Today

Virtually all women and most men are now aligned against that toxic brand of masculinity. No one is asking men to stop being men or for people to stop being sexual beings. What’s happened is that a small group of men are being required to abandon the stereotype that “real men” need to be unrelentingly sexual without regard to context or consent.

The not-unreasonable assumption is that work relationships should be about work. Some organizations have no-dating policies for that reason. If yours doesn’t, remember that you must not take a relationship with a colleague in a romantic or sexual direction if doing so is unwelcome. Whether you can ask a colleague out is the source of much anxiety, especially in all-consuming work environments where people date coworkers because they spend so much time on the job that there’s little opportunity to meet anyone else.

The only way to safely tell what someone else wants is to ask that person. Some men seem to have trouble discerning whether a woman is interested; Charlie Rose and Glenn Thrush said that they thought their feelings were reciprocated when women who received their overtures say they were not. This is not an unsolvable problem. If she’s a work colleague and you’d like her to be something more, here’s what to do: Imagine telling a woman who’s been your friend forever that you’d like to take the relationship in a different direction. Ask in a way that gives her a chance to say that she prefers to remain a friend. No harm, no foul. What if your work colleague says no when she really means yes? Well, then, she’s got to live with that. Let her. Let her change her mind if she wants to.

We all know that deals and crucial networking happen over lunch, dinner, and drinks. Socializing in this manner is fine. But if you do socialize with work colleagues, you need to realize that you can’t behave inappropriately. Roy Price resigned from his job as head of Amazon Studios after Isa Hackett, an Amazon producer, publicly accused him of repeatedly propositioning her in a cab on the way to a work party, telling her, “You’ll love my dick,” and later at the gathering whispering “anal sex” loudly in her ear in the presence of others. Hollywood commentator Nellie Andreeva noted that in a post-Weinstein world Price’s behavior would have hurt Amazon’s ability to attract female showrunners and actors. He would have been “completely ostracized,” an anonymous source told Andreeva.

You can still compliment your colleagues. But there’s a big difference between “I like that dress” and “You look hot in that dress.” What if she really does look hot? Remember, she signed up to be your colleague, not your girlfriend. Treat her like a colleague unless by mutual consent, you change your relationship.

Don’t let the pendulum swing too far the other way and bizarrely avoid women completely. That’s unnecessary, unfair, and illegal: It deprives women of opportunities simply because they are women. You cannot refuse to have closed-door meetings with women unless you refuse to have closed-door meetings with men. Otherwise women will be denied access to all the sensitive information that’s shared only behind closed doors, and that’s a violation of federal law.

Moving forward, male allies will continue to play an important role in fighting harassment: If you see something, say something. It does take courage, but you can use a light touch. If you’re standing around with a bunch of guys and a female colleague walks by, only to have someone say, “Wow, she’s hot,” you can say simply: “I don’t think of her that way. I think of her as a colleague, and that’s the way I suspect she’d like to be thought of.”

Clear takeaways emerge for women, too. If a coworker tries to take a work relationship in a sexual direction, tell him clearly if that’s unwelcome. If you face sexual joking that’s making you uncomfortable, say, “This is making me uncomfortable” and expect it to stop. If you want to shame or jolly someone out of misbehavior while preserving your business relationships, consult Joan’s What Works for Women at Work. Here’s an approach that worked for one woman whose colleague proposed an affair: “I know your wife. She’s my friend. You’re married. There is just no way I would ever consider that. So let’s not go there again.”

But it’s our final piece of advice that signals the tectonic shift: If you are being sexually harassed, report it. We’re not sure if we would have advised that, in such a blanket and unnuanced way, even a year ago.

What we’re seeing today is not the end of sex, or of seduction, or of la différence. What we’re seeing is the demise of a work culture where women must submit to being treated, insistently and incessantly, as sexual opportunities. Most people, when they go to work, want to work. And now they can.

How Do Your Workers Feel About Harassment? Ask Them

by Andrea S. Kramer and Alton B. Harris

If your business is serious about eliminating the risk of sexual harassment—and it should be—you need to approach the problem comprehensively. This means recognizing that sexual harassment is part of a continuum of interconnected behaviors that range from gender bias to incivility to legally actionable assault. All these kinds of misconduct should be addressed collectively, because sexual harassment is far more likely in organizations that experience offenses on the “less severe” end of the spectrum than in those that don’t.

There’s no one-size-fits-all program for eliminating inappropriate gender-related behaviors; the best programs specifically address the characteristics of each workplace’s culture. The vital first step, then, is to get an accurate picture of yours. How? Ask your employees directly. Do they see disparities in career opportunities? Are colleagues or supervisors rude to each other? Is there inappropriate sexual conduct? Do employees feel uncomfortable or unsafe at work?

The best way to find all this out is with a carefully designed employee survey. In this article we’ll offer some key principles for fashioning one, along with a model survey that you can adapt (which incorporates some of the recommendations the EEOC made for surveys in its 2017 proposed enforcement guidance on harassment). Our advice is based on insights we developed while working with major business organizations and conducting several hundred gender-focused workshops and moderated conversations around the United States.

Though we think a workplace climate survey can be immensely valuable, we caution that managers and leaders should proceed only if they’re fully committed to thoroughly and quickly addressing inappropriate behavior in their organizations. Once the surveys are undertaken, they’ll create expectations of remedial action. They might also attract unwanted publicity or be used against the company in future litigation. Those risks, however, are substantially outweighed by the opportunity to develop a work environment that’s free of sexual misconduct, gender bias, and incivility.

Step 1: Communicate with Employees

Inform your employees that you’re undertaking an effort to understand how fair, courteous, and safe their workplace is. The goal is to encourage engaged and completely candid answers to the survey. For that reason, it should be anonymous and administered by a third party, not your HR department. Employees won’t have faith that their answers are confidential if the survey is conducted in-house, and if you don’t offer true anonymity, their responses are less likely to be honest.

It’s crucial for employees to believe that management considers an unbiased and harassment-free workplace a priority and is sincere in its commitment to that objective. That will happen only if senior management openly endorses the initiative, communicates the importance of supporting it to the entire management team, and periodically speaks to all employees about it.

Employees also need to believe that the end result will be better policies for everyone. This last point can’t be emphasized too strongly. If the steps you take to combat inappropriate gender-related behaviors are seen solely as efforts to “protect” women because of their vulnerability, the initiative will backfire.

The first organization-wide letter to employees might begin with a statement like this:

We are gathering information on a confidential basis to better understand our business’s workplace climate. Our goal is to ensure that all employees receive equal opportunities, respect, and resources in a workplace that is free of incivility and does not tolerate inappropriate sexual conduct.

The survey that you’ll receive shortly is the first step toward achieving that objective.

We have hired a third-party administrator to conduct the survey on a strictly anonymous basis. Your answers and identity will be carefully protected from disclosure.

The administrator will contact you separately and detail its procedures for preserving anonymity.

The survey you’ll receive is divided into four parts: gender bias, incivility, inappropriate sexual conduct, and overall workplace climate. All four areas are important, so please be as candid as possible in giving your views.

Employees should also be told that only the third-party administrator will see the raw survey results and that it will provide an analysis of those results to management. Once management receives that report, employees should be advised of the nature of and timetable for next steps.

We suggest that you emphasize that because the survey is anonymous, your organization cannot investigate or remedy specific claims raised by respondents—unless the incidents are separately reported in accordance with existing company procedures. Urge your employees to use those procedures if appropriate.

Step 2: Draw Up Your Survey

Whether you start with the assessment that we provide in this article or create your own questions, you should tailor your survey to your organization’s culture and climate. Keep in mind the following:

Avoid questions that could be used—or thought to be used—to identify participants, such as those about title, age, tenure with the company, responsibilities, and workplace location.

Don’t ask about marital or domestic status, sexual preference, children, or prior involvement in sexual misconduct investigations or proceedings. An inappropriate question in a job interview is equally inappropriate in a workplace climate survey.

Keep the survey on point. Resist the temptation to use it as an opportunity to ask employees more broadly about their experiences, expectations, and future plans.

Make the survey short and unambiguous. It should take no more than 10 minutes to finish. You may use true/false, multiple choice, or open-ended questions, but in our experience, the most useful approach is to incorporate a scale. Develop a series of statements that participants will be asked to indicate their degree of agreement with, using a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). With statements that are intended to examine the frequency of specific behaviors, use a scale of 1 (very frequently) to 4 (never).

Step 3: Evaluate

A workplace climate survey needs no statistical evaluation beyond a simple tabulation. You’re just attempting to determine whether some of your employees believe there are gender-related problems in your work environment and what those problems are.

Bear in mind that the survey is not an end in itself; it’s a tool to identify whether you need new policies, practices, and procedures to eliminate inappropriate behavior and protect your employees against sexual harassment. Your results may indicate additional steps are necessary. You might need to assemble focus groups, conduct personal interviews, or host roundtable discussions. Since your goal is to ensure you have a welcoming, supportive, and productive workplace, the real work begins once you have a clear picture of your business’s actual climate. Below is a template you can use when constructing your survey:

Model Workplace Climate Survey

Complete the following survey about your experience at XYZ Company, without referring to experiences at any prior organizations. The value of this survey depends directly on getting an accurate view of our workplace culture, so please answer all questions as honestly as possible.

1. Which of the following describes your gender?

Male

Female

Prefer to self-describe (specify)

Prefer not to say

Gender Bias

2. I feel valued by the organization.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

3. I believe my opportunities for career success are negatively affected by my gender.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

4. The people I work with treat me with respect and appreciation.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

5. My views are encouraged and welcomed by my supervisors and senior leaders without regard to my gender.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

6. Career-enhancing assignments and opportunities are disproportionately given to men.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

Civility

7. My coworkers are courteous and friendly.

8. I’m aware of unpleasant and negative gossip in the workplace.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

9. I’m aware of abusive, disrespectful, or hostile treatment of employees.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

10. I’m aware of bullying behavior in the workplace.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

11. There are adverse consequences for senior leaders who are abusive, disrespectful, or hostile.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

12. I have been criticized for my personal communication style or appearance.

(1) Very frequently

(2) Somewhat frequently

(3) Not at all frequently

(4) Never

13. All individuals are valued here.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

Inappropriate Sexual Conduct

14. I have experienced or witnessed unwanted physical conduct in the workplace or by coworkers away from the workplace.

(1) Very frequently

(2) Somewhat frequently

(3) Not at all frequently

(4) Never

15. I have witnessed or heard of offensive or inappropriate sexual jokes, innuendoes, banter, or comments in our workplace.

(1) Very frequently

(2) Somewhat frequently

(3) Not at all frequently

(4) Never

16. I have witnessed or heard of the electronic transmission of sexually explicit materials or comments by coworkers.

(1) Very frequently

(2) Somewhat frequently

(3) Not at all frequently

(4) Never

17. I have received sexually inappropriate phone calls, text messages, or social media attention from a coworker.

(1) Very frequently

(2) Somewhat frequently

(3) Not at all frequently

(4) Never

18. I have been asked or have witnessed inappropriate questions of a sexual nature.

(1) Very frequently

(2) Somewhat frequently

(3) Not at all frequently

(4) Never

19. I have been the subject of conduct that I consider to be sexual harassment.

20. Managers here tolerate or turn a blind eye to inappropriate sexual conduct.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

21. I feel unsafe at work because of inappropriate sexual conduct by some individuals.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

22. I’ve seen career opportunities be favorably allocated on the basis of existing or expected sexual interactions.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

23. I would be comfortable reporting inappropriate sexual conduct by a coworker.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

24. I would be comfortable reporting inappropriate sexual conduct by a supervisor.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

Overall Workplace Climate

25. My productivity has been affected by inappropriate gender-related behavior in the workplace.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

26. I have considered leaving my job because of inappropriate gender-related behavior in the workplace.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

27. Star performers are held to the same standards as other employees with respect to inappropriate gender-related behavior.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

28. I have experienced or witnessed inappropriate gender-related behavior by third parties (such as customers, vendors, and suppliers) associated with our organization.

(1) Very frequently

(2) Somewhat frequently

(3) Not at all frequently

(4) Never

29. The organization’s policies and processes with respect to prohibiting and reporting inappropriate gender-related behavior are easy to understand and follow.

(1) Strongly disagree

(2) Disagree

(3) Slightly disagree

(4) Neither agree nor disagree, or have no opinion

(5) Slightly agree

(6) Agree

(7) Strongly agree

Who’s Harassed, and How?

by Heather McLaughlin

Imagine 100 young women. How many do you think will be sexually harassed by the age of 31?

Don’t think just of the cases you’ve heard about in the news. Yes, the allegations about Harvey Weinstein, Roger Ailes, Charlie Rose, Matt Lauer, and many other famous and powerful men are disturbing, but the wave of revelations that followed are just as important. Thousands more women have broken their silence and publicly shared their #MeToo stories. It’s now clear that sexual harassment is experienced by police officers, construction workers, accountants, kindergarten teachers, and workers in every occupation and industry around the world.

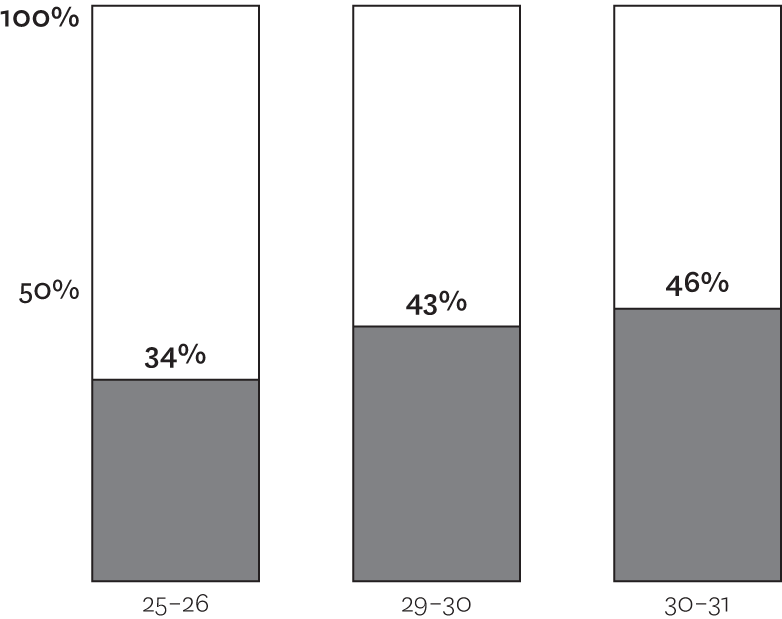

So, again, how many of those 100 women will be sexually harassed by age 31? At least 46%.

Is that figure surprising? Higher than you thought? Lower? One of the pernicious aspects of harassment is the difficulty of knowing precisely what’s going on, how much it’s going on, and who’s doing it. I suspect the number is actually higher than this because of the nature of data collection and the fact that harassment is highly underreported, as I’ll explore in this article. But data sets on it do exist. And the data we have puts the number at 46%.

That figure and the statistics in the following charts come from the Youth Development Study, which surveyed more than 1,000 individuals—both men and women—from St. Paul, Minnesota, from their freshman year in high school until their late thirties. Questions about sexual harassment were included in the surveys that participants took three times: when they were age 25 to 26, age 29 to 30, and age 30 to 31. The effort was the most comprehensive examination of workplace sexual harassment ever done in a longitudinal study, despite its geographic confines. Here are some of its findings:

Prevalence of Harassment

By their mid-twenties, one in three women had been sexually harassed, and as they grew older, that figure progressively rose, to nearly one in two. The latter two surveys asked just whether the women had experienced sexual harassment within the past year. I can safely project that if the data covered all the years in the women’s late twenties or their entire lifetimes, the rate would be higher still.

Percentage of women who have experienced sexual harassment

At three different ages

Note: Estimates include only women who responded to all three waves of data collection.

Behaviors Endured

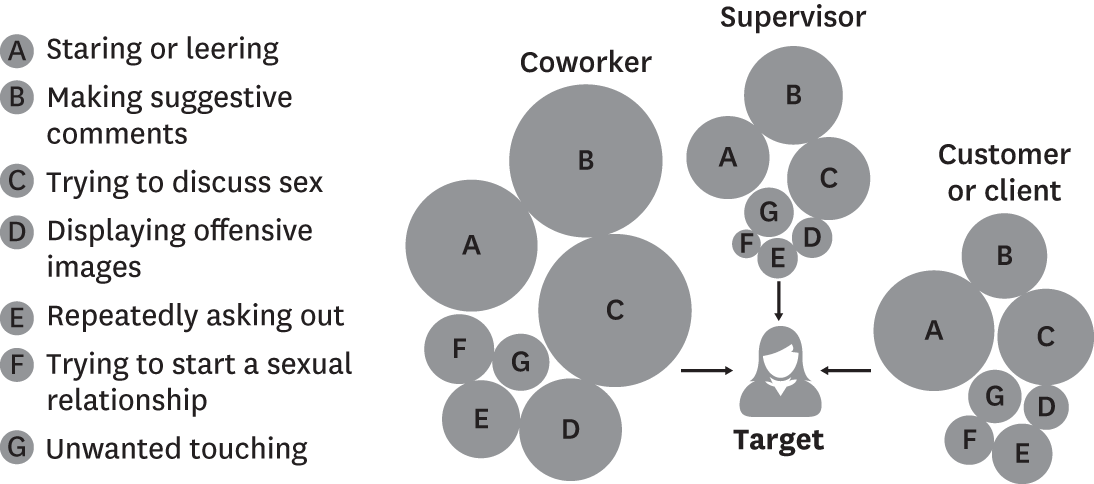

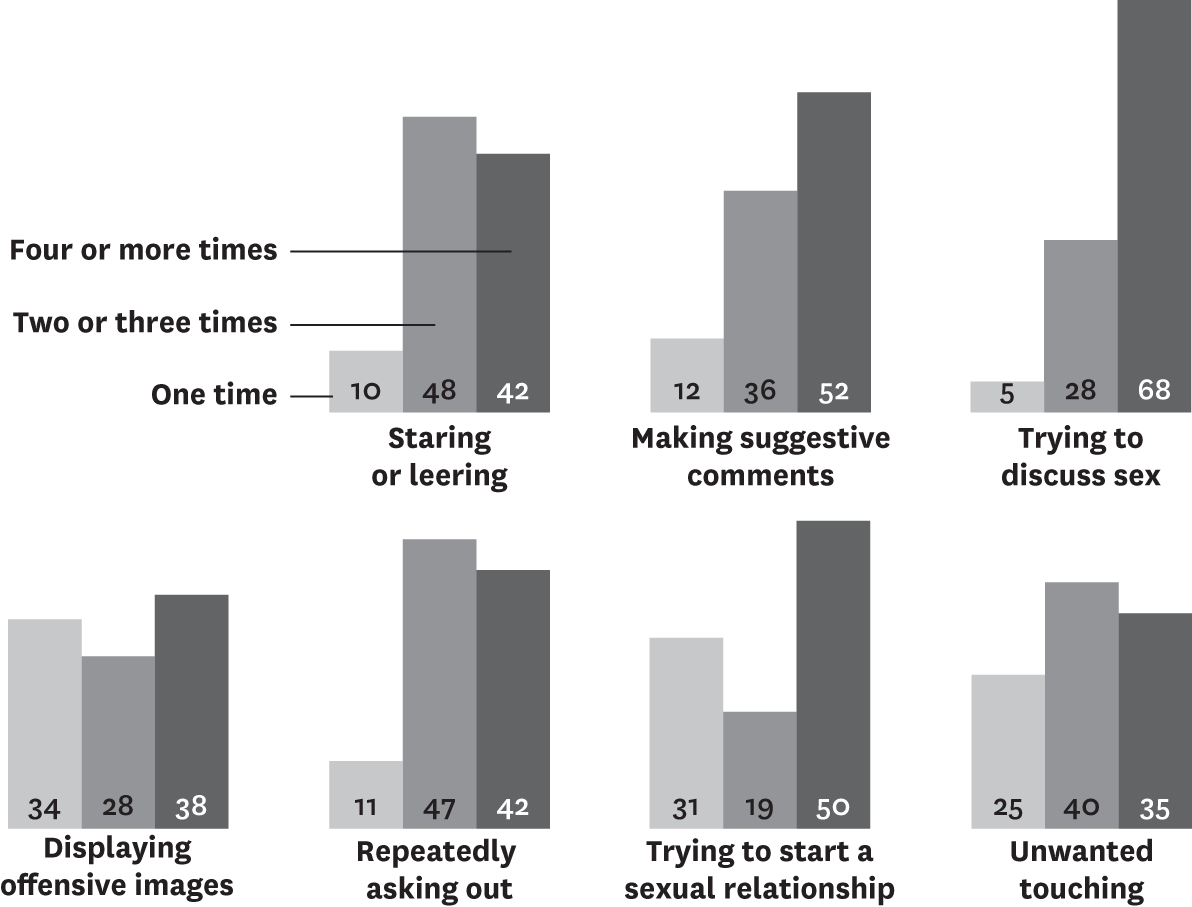

When respondents were 30 to 31 years old, they were asked if they had experienced one or more harassing behaviors in the past year. More than one-third of women said they had. The more severe a behavior was, the less frequent it tended to be; leering was more common, for instance, than unwanted touching. But the numbers on all types of behaviors were astonishingly high for a one-year period.

Percentage of women experiencing one or more harassing behaviors within a single year

Percentage of women experiencing harassing behaviors

Power Dynamics

The typical harassment scenario we see in the news involves a clear organizational power dynamic: boss and subordinate. So it may surprise some people to learn that most harassment involves a lateral relationship: a coworker who doesn’t officially have power over the target. Harassment is still a crime rooted in power, but it’s important to look at lateral dynamics to understand who’s harassing women woman and how.

Harassers’ work relationship to targets

Of the nearly 400 harassers reported by women in one analysis, coworkers were responsible for three times more reported incidents than supervisors.

Frequency of types of harassment

Note: Respondents could report more than one harasser.

Frequency

Sexual harassment at work is far from an isolated experience. The regularity of these incidents makes it evident that a larger culture of harassment exists; it’s not just a few bad apples who are abusing their power. The data from the survey of respondents at age 30 to 31 shows that more targets endured multiple instances of harassing behaviors than experienced a single incident. This was true across every type of harassment.

Most harassing behaviors occur multiple times per year

Percentage of harassed women who said they experienced the behaviors:

Percentage of harassed women experiencing behavior

Note: May not add up to 100% because of rounding.

Underreporting

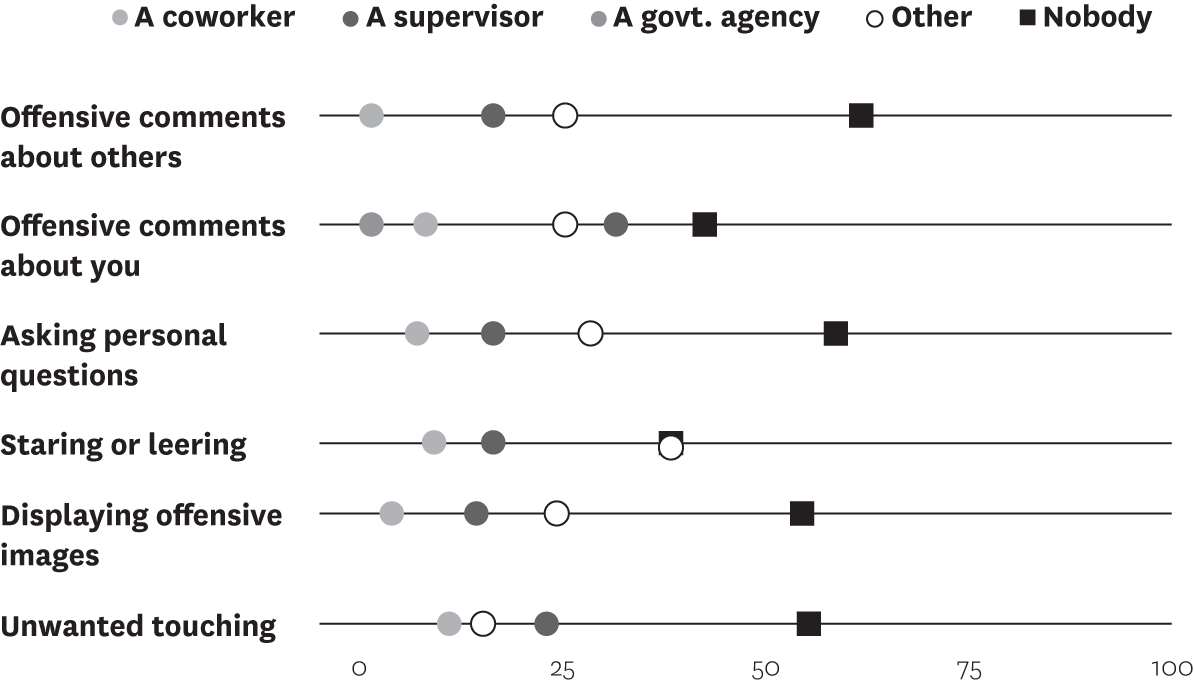

Some people have expressed skepticism about the recent wave of harassment claims, questioning why women didn’t come forward sooner. But the data—in this case from the survey taken when respondents were 29 to 30—supports the assertion that many are harassed but few report it.

If targets told anyone at all, they tended to confide in a colleague or friend rather than someone in a position to address the problem.

(Note that the list of harassing behaviors differs slightly here because of survey design changes in the year this was asked.)

Who is notified of harassment

Percentage of harassed women who informed:

Note: Respondents could report harassment to more than one person/agency.

The many reasons that harassment goes unreported have been deeply explored. But one surprising reason may be that targets do not recognize some experiences as harassment, despite disliking them. A surprisingly low percentage of people who said they’d endured harassing behaviors at age 30 to 31 perceived them to be actual harassment.

Gender differences in experiences of sexual harassment

Percentage of people who experienced one or more sexually harassing behaviors: 36%

Even those who experienced repeated harassment often downplayed the seriousness or inappropriateness of some interactions. The numbers indicate that this may be especially true for men. At the same time, women often experience behaviors like catcalling and other inappropriate comments and gestures in settings besides work, which may account for why many don’t label them an illegal form of discrimination when they occur on the job. Perhaps more would now, in this particular cultural moment, but that is a question researchers have yet to answer. While it seems as if attitudes about what constitutes harassment and cultural acceptance of speaking out about it are changing, we won’t know for sure if this is a permanent shift until several more years of data are collected.

It will be crucial to build on this data with follow-up questions in upcoming surveys to see if the dynamic shifts. If this extraordinary moment actually ushers in a new cultural norm and systemic changes, there should be a dramatic drop in the number of cases that go unreported and a significant rise in the percentage of people characterizing the behavior they endure as harassment. Organizations must change, as the costs of sexual harassment are high to both targets and their employers. Time magazine named the silence breakers the 2017 Person of the Year. Perhaps 2018 will be dedicated to the change makers.

Originally published in January 2018. Reprint BG1801