“A Players” or “A Positions”?

The Strategic Logic of Workforce Management.

by Mark A. Huselid, Richard W. Beatty, and Brian E. Becker

A GREAT WORKFORCE IS made up of great people. What could be more intuitively obvious? Is it any wonder, then, that so many companies have devoted so much energy in recent years to identifying, developing, and retaining what have come to be known as “A players”? Firms like GE, IBM, and Microsoft all have well-developed systems for managing and motivating their high-performance and high-potential employees—and for getting rid of their mediocre ones. Management thinkers have widely endorsed this approach: Larry Bossidy, in the best-selling book Execution, for example, calls this sort of differentiation among employees “the mother’s milk of building a performance culture.”

But focusing exclusively on A players puts, well, the horse before the cart. High performers aren’t going to add much value to an organization if they’re smoothly and rapidly pulling carts that aren’t going to market. They’re going to be effective only when they’re harnessed to the right cart—that is, engaged in work that’s essential to company strategy. This, too, may seem obvious. But it’s surprising how few companies systematically identify their strategically important A positions—and then focus on the A players who should fill them. Even fewer companies manage their A positions in such a way that the A players are able to deliver the A performance needed in these crucial roles.

While conventional wisdom might argue that the firms with the most talent win, we believe that, given the financial and managerial resources needed to attract, select, develop, and retain high performers, companies simply can’t afford to have A players in all positions. Rather, we believe that the firms with the right talent win. Businesses need to adopt a portfolio approach to workforce management, placing the very best employees in strategic positions, good performers in support positions, and eliminating nonperforming employees and jobs that don’t add value.

We offer here a method for doing just that, drawing on the experience of several companies that are successfully adopting this approach to workforce management, some of which we have worked with in our research or as consultants. One thing to keep in mind: Effective management of your A positions requires intelligent management of your B and C positions, as well.

Identifying Your A Positions

People traditionally have assessed the relative value of jobs in an organization in one of two ways. Human resource professionals typically focus on the level of skill, effort, and responsibility a job entails, together with working conditions. From this point of view, the most important positions are those held by the most highly skilled, hardest-working employees, exercising the most responsibility and operating in the most challenging environments.

Economists, by contrast, generally believe that people’s wages reflect the value they create for the company and the relative scarcity of their skills in the labor market. Thus, the most important jobs are those held by the most highly paid employees. The trouble with both of these approaches is that they merely identify which jobs the company is currently treating as most important, not the ones that actually are. To do that, one must not work backward from organization charts or compensation systems but forward from strategy.

That’s why we believe the two defining characteristics of an A position are first, as you might expect, its disproportionate importance to a company’s ability to execute some part of its strategy and second—and this is not nearly as obvious—the wide variability in the quality of the work displayed among the employees in the position.

Plainly, then, to determine a position’s strategic significance, you must be clear about your company’s strategy: Do you compete on the basis of price? On quality? Through mass customization? Then you need to identify your strategic capabilities—the technologies, information, and skills required to create the intended competitive advantage. Walmart’s low-cost strategy, for instance, requires state-of-the-art logistics, information systems, and a relentless managerial focus on efficiency and cost reduction. Finally, you must ask: What jobs are critical to employing those capabilities in the execution of the strategy?

Such positions are as variable as the strategies they promote. Consider the retailers Nordstrom and Costco. Both rely on customer satisfaction to drive growth and shareholder value, but what different forms that satisfaction takes: At Nordstrom it involves personalized service and advice, whereas at Costco low prices and product availability are key. So the jobs critical to creating strategic advantage at the two companies will be different. Frontline sales associates are vital to Nordstrom but hardly to be found at Costco, where purchasing managers are absolutely central to success.

The point is, there are no inherently strategic positions. Furthermore, they’re relatively rare—less than 20% of the workforce—and are likely to be scattered around the organization. They could include the biochemist in R&D or the field sales representative in marketing.

So far, our argument is straightforward. But why would variability in the performance of the people currently in a job be so important? Because, as in other portfolios, variation in job performance represents upside potential—raising the average performance of individuals in these critical roles will pay huge dividends in corporate value. Furthermore, if that variance exists across companies, it may also be a source of competitive advantage for a particular firm, making the position strategically important.

Sales positions, fundamental to the success of many a company’s strategy, are a good case in point: A salesperson whose performance is in the 85th percentile of a company’s sales staff frequently generates five to 10 times the revenue of someone in the 50th percentile. But we’re not just talking about greater or lesser value creation—we’re also talking about the potential for value creation versus value destruction. The Gallup organization, for instance, surveyed 45,000 customers of a company known for customer service to evaluate its 4,600 customer service representatives. The reps’ performance ranged widely: The top quartile of workers had a positive effect on 61% of the customers they talked to, the second quartile had a positive effect on only 40%, the third quartile had a positive effect on just 27%—and the bottom quartile actually had, as a group, a negative effect on customers. These people—at the not insignificant cost to the company of roughly $40 million a year (assuming average total compensation of $35,000 per person)—were collectively destroying value by alienating customers and, presumably, driving many of them away.

Although the $40 million in wasted resources is jaw-dropping, the real significance of this situation is the huge difference that replacing or improving the performance of the subpar reps would make. If managers focused disproportionately on this position, whether through intensive training or more careful screening of the people hired for it, company performance would improve tremendously.

The strategic job that doesn’t display a great deal of variability in performance is relatively rare, even for those considered entry-level. That’s because performance in these jobs involves more than proficiency in carrying out a task. Consider the job of cashier. The generic mechanics aren’t difficult. But if the position is part of a retail strategy emphasizing the customers’ buying experience, the job will certainly involve more than scanning products and collecting money with a friendly smile. Cashiers might, for example, be required to take a look at what a customer is buying and then suggest other products that the person might want to consider on a return visit. In such cases, there is likely to be a wide range in people’s performance.

Some jobs may exhibit high levels of variability (the sales staff on the floor at a big-box store like Costco, for example) but have little strategic impact (because, as we have noted, Costco’s strategy does not depend on sales staff to ensure customer satisfaction). Neither dramatically improving the overall level of performance in these jobs nor narrowing the variance would present an opportunity for improving competitive advantage.

Alternatively, some jobs may be potentially important strategically but currently represent little opportunity for competitive advantage since everyone’s performance is already at a high level. That may either be because of the standardized nature of the job or because a company or industry has, through training or careful hiring, reduced the variability and increased the mean performance of workers to a point where further investment isn’t merited. A pilot, for example, is a key contributor to most airlines’ strategic goal of safety, but owing to regular training throughout pilots’ careers and government regulations, most pilots perform well. Although there definitely is a strategic downside if the performance of some pilots were to fall into the unsafe category, improving pilot performance in the area of safety is unlikely and, even if marginal gains are possible, unlikely to provide an opportunity for competitive advantage.

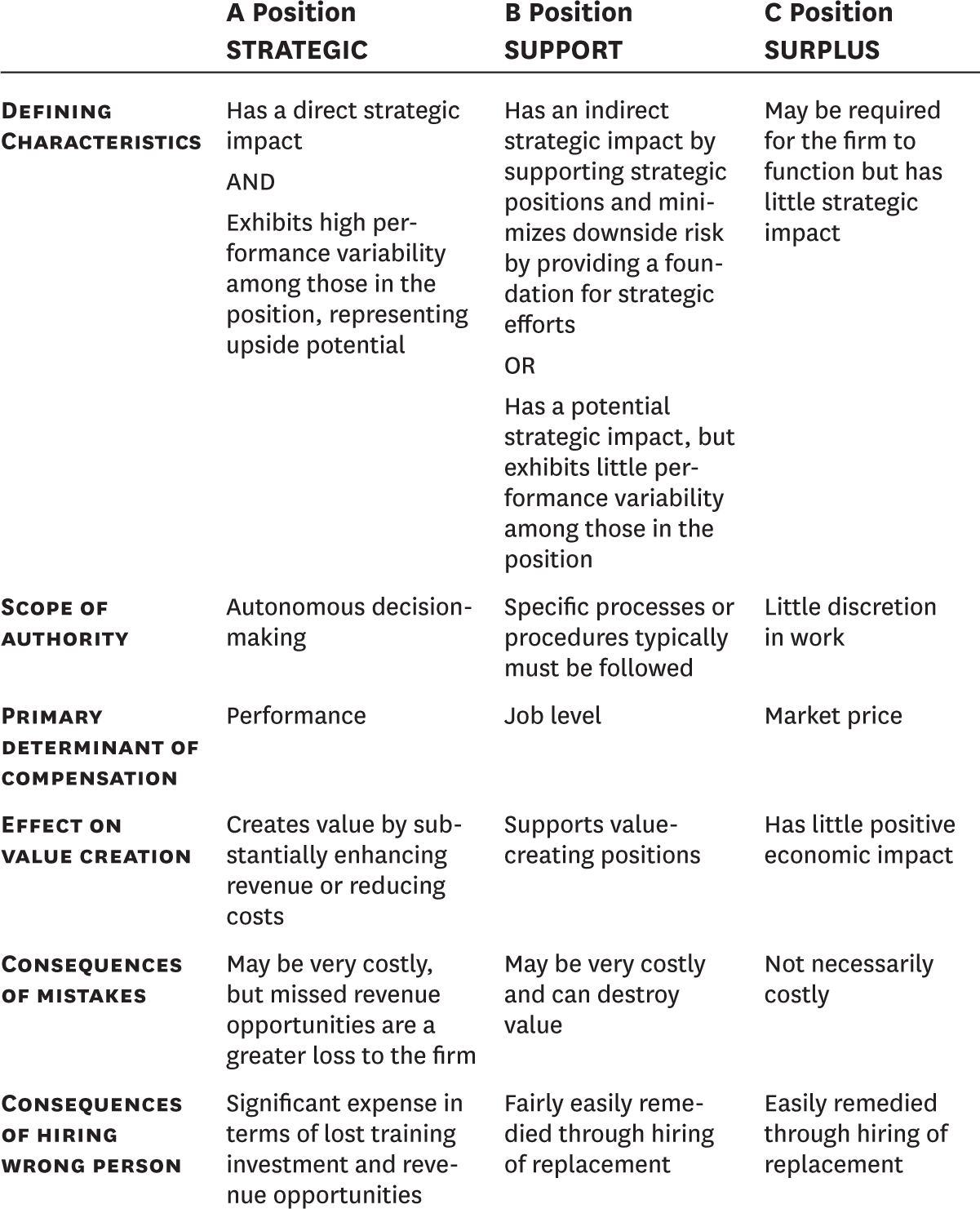

So a job must meet the dual criteria of strategic impact and performance variability if it is to qualify as an A position. From these two defining characteristics flow a number of others—for example, a position’s potential to substantially increase revenue or reduce costs—that mark an A position and distinguish it from B and C positions. B positions are those that are either indirectly strategic through their support of A positions or are potentially strategic but currently exhibit little performance variability and therefore offer little opportunity for competitive advantage. Although B positions are unlikely to create value, they are often important in maintaining it. C positions are those that play no role in furthering a company’s strategy, have little effect on the creation or maintenance of value—and may, in fact, not be needed at all. (For a comparison of some attributes of these three types of positions, see the exhibit “Which jobs make the most difference?”)

Which jobs make the most difference?

An A position is defined primarily by its impact on strategy and by the range in the performance level of the people in the position. From these two characteristics flow a number of other attributes that distinguish A positions from B and C jobs.

It’s important to emphasize that A positions have nothing to do with a firm’s hierarchy—which is the criterion executive teams so often use to identify their organizations’ critical and opportunity-rich roles. As natural as it may be for you, as a senior executive, to view your own job as among a select group of vital positions in the company, resist this temptation. As we saw in the case of the cashier, A positions can be found throughout an organization and may be relatively simple jobs that nonetheless need to be performed creatively and in ways that fit and further a company’s unique strategy.

A big pharmaceutical firm, for instance, trying to pinpoint the jobs that have a high impact on the company’s success, identifies several A positions. Because its ability to test the safety and efficacy of its products is a required strategic capability, the head of clinical trials, as well as a number of positions in the regulatory affairs office, are deemed critical. But some top jobs in the company hierarchy, including the director of manufacturing and the corporate treasurer, are not. Although people in these jobs are highly compensated, make important decisions, and play key roles in maintaining the company’s value, they don’t create value through the firm’s business model. Consequently, the company chooses not to make the substantial investments (in, say, succession planning) in these positions that it does for more strategic jobs.

A positions also aren’t defined by how hard they are to fill, even though many managers mistakenly equate workforce scarcity with workforce value. A tough job to fill may not have that high potential to increase a firm’s value. At a high-tech manufacturing company, for example, a quality assurance manager plays a crucial role in making certain that the products meet customers’ expectations. The job requires skills that may be difficult to find. But, like the airline pilots, the position’s impact on company success is asymmetrical. The downside may indeed be substantial: Quality that falls below Six Sigma levels will certainly destroy value for the company. But the upside is limited: A manager able to achieve a Nine Sigma defect rate won’t add much value because the difference between Six Sigma and Nine Sigma won’t be great enough to translate into any major value creation opportunity (although the difference between Two- and Three-Sigma defect rates may well be). Thus, while such a position could be hard to fill, it doesn’t fit the definition of an A position.

Managing Your A Positions

Having identified your A positions, you’ll need to manage them—both individually and as part of a portfolio of A, B, and C positions—so that they and the people in them in fact further your organization’s strategic objectives.

A first and crucial step is to explain to your workforce clearly and explicitly the reasons that different jobs and people need to be treated differently. Pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline is identifying those positions, at both the corporate and business-unit levels, that are critical to the company’s success in a rapidly changing competitive environment. As part of that initiative, the company developed a statement of its workforce philosophy and management guidelines. One of these explicitly addresses “workforce differentiation” and reads, in part: “It is essential that we have key talent in critical positions and that the careers of these individuals are managed centrally.”

But communication is just the beginning. A positions also require a disproportionate level of investment. The performance of people in these roles needs to be evaluated in detail, these individuals must be actively developed, and they need to be generously compensated. Also, a pipeline must be created to ensure that their successors are among the best people available. IBM is a company making aggressive investments on each of these four fronts.

In recent years, IBM has worked to develop what it calls an “on-demand workforce,” made up of people who can quickly put together or become part of a package of hardware, software, and consulting services that will meet the specific needs of an individual customer. As part of this effort, IBM has sought to attract and retain certain individuals with what it terms the “hot skills” customers want in such bundled offerings.

In the past year or so, the company has also focused on identifying its A positions. The roster of such positions clearly will change as IBM’s business does. But some, such as the country general manager, are likely to retain their disproportionate value. Other strategic roles include midlevel manager positions, dubbed “deal makers,” responsible for the central strategic task of pulling together, from both inside and outside the company, the diverse set of products, software, and expertise that a particular client will find attractive.

Evaluation

Because of their importance, IBM’s key positions are filled with top-notch people: Obviously, putting A players in these A positions helps to ensure A performance. But IBM goes further, taking steps to hold its A players to high standards through an explicit process—determining the factors that differentiate high and low performance in each position and then measuring people against those criteria. The company last year developed a series of 10 leadership attributes—such as the abilities to form partnerships with clients and to take strategic risks—each of which is measured on a four-point scale delineated with clear behavioral benchmarks. Individuals assess themselves on these attributes and are also assessed by others, using 360-degree feedback.

Development

Such detailed evaluation isn’t very valuable unless it’s backed up by a robust professional development system. Drawing on the strengths and weaknesses revealed in their evaluations and with the help of tools available on the company’s intranet, people in IBM’s A positions are required to put together a development program for themselves in each of the 10 leadership areas.

This is only one of numerous development opportunities offered to people in A positions. In fact, more than $450 million of the $750 million that IBM spends annually on employee development is targeted at either fostering hot skills (both today’s and those expected to be tomorrow’s) or the development of people in key positions. A senior-level executive devotes all of his time to programs designed to develop the executive capabilities of people in these jobs.

Compensation

IBM supports this disproportionate investment in development with an even more disproportionate compensation system. Traditionally at IBM, even employees with low performance ratings had received regular salary increases and bonuses. Today, annual salary increases go to only about half the workforce, and the best-performing employees get raises roughly three times as high as those received by the simply strong performers.

Succession

Perhaps most important, IBM has worked to formalize succession planning and to build bench strength for each of its key positions, in part by investing heavily in feeder jobs for those roles. People in these feeder positions are regularly assessed to determine if they are “ready now,” “one job away,” or “two jobs away” from promotion into the strategically important roles. “Pass-through” jobs, in which people can develop needed skills, are identified and filled with candidates for the key strategic positions. For example, the position of regional sales manager is an important pass-through job on the way to becoming a country general manager. In this way, IBM ensures that its A people will in fact be ready to fill its top positions.

Managing Your Portfolio of Positions

Intelligently managing your A positions can’t be done in isolation. You also need strategies for managing your B and C positions and an understanding of how all three strategies work together. We find it ironic that managers who embrace a portfolio approach in other areas of the business can be slow to apply this type of thinking to their workforce. All too frequently, for example, companies invest in their best and worst employees in equal measure. The unhappy result is often the departure of A players, discouraged by their treatment, and the retention of C players.

To say that you need to disproportionately invest in your A positions and players doesn’t mean that you ignore the rest of your workforce. B positions are important either as support for A positions (as IBM’s feeder positions are) or because of any potentially large downside implications of their roles (as with the airline pilots). Put another way, although you aren’t likely to win with your B positions, you can certainly lose with them.

As for those nonstrategic C positions, you may conclude after careful analysis that, just as you need to weed out C players over time, you may need to weed out your C positions, by outsourcing or even eliminating the work.

Roche is one firm that is placing more emphasis on the strategic value of positions themselves. Over the past few years, the pharmaceutical company has been looking at different positions to determine which are necessary for maintaining competitive advantage. Regardless of how well a person performs in a role, if that position is no longer of strategic value, the job is eliminated. For example, Roche looked at the strategic value provided by data services in a recent project and as a result decided which positions needed to be added, which needed to change (or be moved)—and which, such as data center services (DCS) engineer, needed to be eliminated. In a similar manner, another pharmaceutical firm, Wyeth Consumer Healthcare, following a strategic decision to focus on large customers, eliminated what had been a strategic position for the company—middle-market account manager—as well as staff that supported the people in this position.

The ultimate aim is to manage your portfolio of positions so that the right people are in the right jobs, paying particular attention to your A positions. First, using performance criteria developed for determining who your A, B, and C players are, calculate the percentage of each currently in A positions. Then act quickly to get C players out of A positions, replace them with A players, and work to help B players in A positions become A players. GlaxoSmithKline currently is engaged in an initiative to push both line managers and HR staff to ensure that only top-tier employees (as determined by their performance evaluations) are in the company’s identified key positions.

Making Tough Choices

Despite the obvious importance of developing high-performing employees and supporting the jobs that contribute most to company success, firms that routinely make difficult decisions about R&D, advertising, and manufacturing strategies rarely show the same discipline when it comes to their most valuable asset: the workforce. In fact, in our long experience, we’ve found that firms with the most highly differentiated R&D, product, and marketing strategies often have the most generic or undifferentiated workforce strategies. When a manager at one of these companies does make a tough choice in this area, the decision often relates to the costs rather than the value of the workforce. (The sidebar “Are we differentiating enough?” can help you determine whether you are making the distinctions likely to create workforce value.)

It would be nice to live in a world where we didn’t have to make hard decisions about the workforce, but we don’t. Strategy is about making choices, and correctly assessing employees and roles are two of the most important. For us, the essence of the issue is the distinction between equality and equity. Over the years, HR practices have evolved in a way that increasingly favors equal treatment of most employees within a given job. But today’s competitive environment requires a shift from treating everyone the same to treating everyone according to his or her contribution.

We understand that this approach may not be for everyone, that increasing distinctions between employees and among jobs runs counter to some companies’ cultures. There is, however, a psychological as well as a strategic benefit to an approach that initially focuses on A positions: Managers who are uncomfortable with the harsh A and C player distinction—especially those in HR, many of whom got into the business because they care about people—may find the idea of first differentiating between A and C positions more palatable. But shying away from making the more personal distinctions is also unwise. We all know that effective business strategy requires differentiating a firm’s products and services in ways that create value for customers. Accomplishing this requires a differentiated workforce strategy, as well.

Originally published in December 2005. Reprint R0512G