Chapter 12. Talent Investment Analysis: Catalyst for Change

Chapter 1, “Making HR Measurement Strategic,” noted that decision sciences evolve not simply when leaders within the profession develop logical and strategic models and measures, but when those models and measurement systems become integrated with the logical models and management systems that are used outside the profession. Finance and marketing frameworks are powerful because every business leader, regardless of professional background, is expected to understand basic financial or marketing logic. The ultimate test of any measurement and analysis system is simple: Does it improve decisions about vital resources where they matter most? Regarding talent, the decisions that matter often occur outside the HR function.

We envision a future in which leaders throughout organizations increasingly understand and are held accountable for the quality of their decisions about talent. They must have a sophisticated understanding of the connections between investments in HR programs and their effects on strategic success. Today organization leaders measure talent investments with a heavy reliance on accounting. As we have seen, accounting logic often provides valuable frameworks to track how traditional resources such as cash and time are spent on HR programs and employees. Unfortunately, however, this approach is often inadequate, and even dangerous, when it is the sole arbiter of HR investments. The increasing importance of talent resources to future strategic success means organizations that make better talent decisions will achieve their strategic missions more effectively.

This means that organizations must stop tolerating exclusive reliance on rudimentary cost-based frameworks for HR investments. Although this certainly presents an important challenge for leaders outside the HR profession, it also holds the HR profession to a high standard. If we expect leaders to act with more sophistication, we can help that process along by providing frameworks that enable more sophistication. The frameworks in this book provide HR leaders with ways to do that—and to demonstrate that the insights they provide often improve decisions, thereby improving organizational effectiveness.

Better Answers to Fundamental Questions

Recall the questions we posed at the beginning of Chapter 1. Remember that we challenged you to consider how well your organization could address the following questions or requests if they were posed by your CEO or other business leaders outside the HR function. Now that you’ve read this book, you can see that each question referred to one or more chapters, and those chapters have given you tools for a more sophisticated, logical, and analytical approach.

Absence Means More Than Just Getting the Work Done

I know that on any given day, about 5 percent of our employees are absent. Yet everyone seems to be able to cover for the absent employees, and the work seems to get done. Should we try to reduce this absence rate, and if we did, what would be the benefit to our organization?

Chapter 3, “The Hidden Costs of Absenteeism,” showed that although employees may be able to cover for absent employees and the work may be completed, much deeper issues must be considered. Chapter 3 showed how to calculate the costs of paying employees who aren’t at work and uncovered the hidden costs of overtime or contract employees needed to fill in for the absent employees. We noted that even if the work is getting done, the extra cost of supervisory time managing absence may be substantial. Thus, a more reasoned approach would use the diagnostic elements in Chapter 3 to look beyond whether the work is getting done and ask whether it is being accomplished with the optimum level of human capital investment. As Chapter 3 showed, many strategies can reduce absence, such as providing absent employees with assistance to mitigate the causes of absence (such as the need to take time off to care for sick children or parents) and providing explicit incentives to encourage and reward attendance.

We also noted that the tools we provided to examine absence patterns and costs may produce counterintuitive insights. For example, we showed that increasing company payments for medications to treat chronic diseases might actually produce a net gain in workforce productivity, thereby reducing presenteeism (employees attending work when they are ill). In short, it isn’t as simple as reducing absence whenever it occurs. Instead, a judicious approach focuses on where absence costs are highest and considers investments to both reduce absence and encourage employees to manage optimally their decisions on whether to attend work.

Turnover Isn’t Always a Bad Thing

Our turnover rate among engineers is 10 percent higher than that of our competitors’. Why hasn’t HR instituted programs to get it down to the industry levels? What are the costs or benefits of employee turnover?”

As discussed in Chapter 4, “The High Cost of Employee Separations,” the effects of employee separations, whether dictated by the employer (such as layoffs and dismissals) or by the employee (such as voluntary retirements or quits), carry an array of costs and benefits. Separations carry both obvious and hidden costs.

As discussed, the costs of processing employee separations are merely the tip of the iceberg. To appreciate the costs fully requires understanding not only the costs of separating employees, but also the costs of acquiring and developing their replacements. Moreover, instead of considering employee separations solely on the basis of costs, Chapter 4 provided a framework to examine how employee separations affect the quality of the workforce. Separations can increase workforce quality if replacements are of higher quality than those who left and if the costs of replacement don’t overwhelm the increase in value that the replacements provide. We showed that fully accounting for turnover consequences requires looking beyond simply reducing turnover rates, even when the cost savings are significant. We also showed how organizations can move beyond simply assuming that turnover among high performers is dysfunctional and that turnover among low performers is functional.

The key is to consider employee separations as one of many processes that increase or decrease workforce quality, depending on how optimally they are managed. In many ways, employee separations are analogous to employee selection, except that the organization is “selecting” which of its current employees will remain. Organizations do this directly through their decisions about layoffs and dismissals, but they also do it more subtly through their decisions on how to encourage and reward employees for their decisions to stay or leave.

Layoffs Cut More Than Costs

Our total employment costs are higher than our competitors’, so I need you to lay off 10 percent of our employees. It seems “fair” to reduce headcount by 10 percent in every unit, but we project different growth in different units. What’s the right way to distribute the layoffs?

Regarding layoffs, the implications are clear: Layoffs directed solely at labor cost reductions, particularly when they are arbitrarily spread evenly across the workforce, fall far short of the logical and systematic analysis required to optimize workforce quality. Chapter 4 showed that the right answer to a CEO’s request for blanket layoffs or turnover cost reductions is to step back and consider the full array of separation costs and consequences. Organizations that take that approach are likely to discover both hidden costs and potential benefits of employee separations. They are more likely to uncover differences in talent pools that are more pivotal with regard to the effects of separations. Turnover reduction will be directed where it has the greatest net effect on the future quality of the workforce.

When Everyone Is Reducing Employee Health Investments, Is It Smart to Invest More?

In a globally competitive environment, we can’t afford to provide high levels of health care and health coverage for our employees. Many companies are cutting their health coverage, and so must we. There are cheaper health-care and insurance programs that can cut our costs by 15 percent. Why aren’t we offering cheaper health benefits?”

Chapter 5, “Employee Health, Wellness, and Welfare,” showed that employee health and welfare is more than just a source of increasing costs. The tangible effects of rising health-care costs are undeniable, and for many organizations, such costs have a significant effect on profits and financial returns. Yet the less tangible impacts of health and welfare investments on organizational productivity and resilience are equally important. Chapter 5 provided frameworks for estimating the costs of programs aimed at protecting employee health and caring for employee injuries and illnesses, and for estimating the effects of employee health and welfare on important organizational outcomes.

As discussed, employee health affects organizational performance through reductions in the costs of health care, but more subtly through reductions in absence and turnover, and through increases in productivity. Thus, by using combinations of techniques, as we described in our examples, organizations can analyze the effects of investments in employee health and welfare for their direct impact on costs and medical outcomes. In fact, they can go further to estimate the effects of changes in worker health on intermediate outcomes that also affect organizational performance.

The compelling and significant cost reductions that are often possible by reducing health insurance coverage or increasing employee health premium contributions must be tempered with an awareness of the powerful effects of improved employee health on organizational performance. A fixation on reducing the costs of insuring or caring for employees when they are ill may well obscure the significant benefits of investing more resources focused on improving employee health and productivity. Chapter 5 showed that organizations rarely systematically gather the data necessary to appreciate fully the effects of programs on worker health. In addition, it appears to be more effective to keep healthy employees healthy than to wait until they are ill and attempt to correct that. We also showed that the benefits of investments in employee health have proven to be significant in well-designed studies.

Only by understanding fully both the costs and potential benefits of proposed courses of action can organizations hope to optimize their decisions. As the question in this section suggests, business leaders all too often are understandably tempted by large and vivid cost levels to reduce health insurance and health-care programs. Organizations that take a more measured and analytical approach may well discover ways not only to achieve greater net productivity, but also to create more healthy workplaces in the process.

Why Positive Employee Attitudes Are Not Simply “Soft” and Nice to Have

I read that companies with high employee satisfaction have high financial returns, so I want you to develop an employee-engagement measure and hold our unit managers accountable for raising the average employee-engagement in each of their units.

Chapter 6, “Employee Attitudes and Engagement,” showed tantalizing evidence that organizations with better employee attitudes and higher employee engagement are more likely to be rated as “great places to work”—and provide higher returns to their shareholders. However, before you conclude that investing in employee attitude enhancement is the path to double-digit growth and stock appreciation, Chapter 6 provides a framework for getting underneath the numbers. Indeed, under the right circumstances, there are logical and research-based reasons to expect that enhanced employee attitudes and higher employee engagement may lead to better customer service, higher customer loyalty, and improved profits. The popular press has provided many examples. However, the key is the right circumstances.

Chapter 6 showed that employee attitudes are actually a composite of several different elements, each measured in different ways and each affecting organizational outcomes differently. Employee job satisfaction differs from employee commitment, which, in turn, differs from employee engagement. Understanding the differences has proven key to dissecting the logical connections between attitudes and outcomes. Although commitment and satisfaction may drive employee retention, engagement and line of sight may be the key to improving employee service and production behaviors. Leaders who blindly pursue the goal of being rated highly in the “Best Places to Work” survey may miss more subtle opportunities to enhance attitudes and engagement where they matter most. The pivot points where enhanced attitudes and engagement make the greatest difference are not revealed by a blanket approach to enhance overall attitudes.

Chapter 6 also showed that the path from employee attitudes to organizational performance may be indirect. Employee attitudes may work because they lead to a more attractive workplace for high-quality applicants. Alternatively, they may produce their effects through the retention of high-performing and hard-to-replace employees. Or employee attitudes may have a direct effect on work behaviors when more satisfied or engaged employees demonstrate their attitudes to customers or other key constituents. Consistent with the idea of matching the measurement logic to the strategic situation, Chapter 6 showed how to measure the effects of employee attitudes through a behavioral-costing perspective and through a value-profit-chain perspective.

In the end, therefore, savvy HR and business leaders will look well beyond the typical focus on overall organizational attitudes, measures of engagement, or the ratings of “great places to work.” The tantalizing correlation between those ratings and stock appreciation is just the beginning of a dialogue, one that is guided by principles developed over decades of research and analysis. The danger of equating a correlation with a cause is rarely illustrated more vividly than in the naïve mental models of business leaders who assume that the correlation between employee attitudes and stock performance means that the former causes the latter. Immense opportunities for improved decisions and organizational performance arise when the true power of employee attitudes and engagement is understood, and when they are approached with more “hard” science and less “soft” opinion.

Work-Life Fit Is Not Just a “Generational” Thing

I hear a lot about the increasing demand for work-life fit, but my generation found a way to work the long hours and have a family. Is this generation really that different? Are there really tangible relationships between work-life conflict and organizational productivity? If there are, how would we measure them and track the benefits of work-life programs?

Chapter 7, “Financial Effects of Work-Life Programs,” showed that, for many workers, the days of passively accepting work demands that require 70 or even 100 hours per week may be fading. The desire to find a better fit between the demands and rewards of work and the demands and rewards of life outside of work are increasing not only for those with children or aging parents, but for virtually all members of the workforce. A strict accounting approach to talent might suggest that it is best to induce workers to devote as much time as possible to work. After all, how could greater work time be a bad thing? Yet evidence increasingly suggests that employers that invest in programs to help workers find a better fit between work and life outside of work may reap great benefits.

Chapter 7 showed that work-life programs can include child and dependent care, flexible work conditions, options for work leave, information, and organization culture. The chapter also showed that an adequate analysis of such programs involves understanding that simply investing in the program is seldom sufficient. Work-life programs, like other HR programs, require communication, training, and the support of key leaders. The framework of Chapter 7 also showed that the effects of such programs can range from reduced stress to improved attitudes for current employees, which, in turn, lead to greater productivity and reduced turnover and absence. They also can lead to greater workforce quality because the company becomes attractive to whole new groups of job applicants: Increasingly, potential applicants are seeking an approach to work that satisfies their important nonwork goals and demands.

To answer the request for specific, tangible measures of the effects of such programs, Chapter 7 showed that it is often possible to estimate how such programs reduce time away from work by providing employees with ways to accomplish child- and elder-care tasks more easily and with greater advance planning. Naïve business leaders often frame work-life programs as a nice-to-have perquisite for employees, something that they do only when they can afford it, or something that panders to younger employees who lack sufficient work ethic. In reality, however, work-life programs can often be justified as logical investments that provide powerful business benefits in their own right. A correlation exists between enhanced work-life practices and organizational financial and stock performance. Unearthing whether your organization would benefit from improved work-life programs requires a deeper analysis within a framework such as Chapter 7 provides.

The Staffing Supply Chain Can Be As Powerful As the Traditional Supply Chain

We expect to grow our sales 15 percent per year for the next five years. I need you to hire enough sales candidates to increase the size of our sales force by 15 percent a year, and do that without exceeding benchmark costs per hire in our industry.

Is it worth it to invest in a comprehensive assessment program, to improve the quality of our new hires? If we invest more than our competition, can we expect to get higher returns? Where is the payoff to improved selection likely to be the highest?

Cost per hire and time to fill are two of the most frequent HR measures. It’s often possible to save millions of dollars by managing staffing processes to lower such costs. However, it’s also often possible to create multimillion-dollar problems when other factors go unmeasured and ignored. Focusing only on the number and cost of employees hired is seldom appropriate, because it ignores completely the effects of employee sourcing practices on workforce quality. No organization would manage the supply chain for its raw materials or unfinished goods based only on the cost of acquisition and the volume of goods acquired. Yet organizations often manage their talent supply chain based only on whether vacancies are filled and whether costs are kept at or below benchmark levels.

Chapter 8, “Staffing Utility: The Concept and Its Measurement”; Chapter 9, “The Economic Value of Job Performance”; and Chapter 10, “The Payoff from Enhanced Selection,” collectively provided an alternative view. In combination, the chapters provided a logical framework for considering vital factors that determine not only the cost and quantity of talent affected by internal and external staffing, but also the quality of that talent over time. They showed that investments to enhance recruitment, selection, and retention can often pay off handsomely, even when they appear at first to be very costly. They also showed that the idea of simply duplicating the practices of others or setting benchmark cost levels based on what others do likely overlooks lucrative opportunities for unique competitive success through competing better in the market for talent. The frameworks provided in these chapters allow business leaders to integrate the effects of investments in higher-quality applicant pools with investments in more valid testing and with investments in enhanced retention of those hired. We saw that greater accuracy in selection does little good without a sufficiently large and high-quality applicant pool, and recruiting higher-quality applicants may do little good without sufficiently valid selection. Optimizing is the key, not maximizing the individual elements.

Moreover, these chapters showed that it is possible to estimate the amount of variability in job performance, and thus to translate the effects of programs to enhance performance quality directly into monetary units. The ability to estimate the relative value of performance differences across different roles and positions opens the door to systematic analysis of “pivotal” roles rather than a traditional focus merely on “important” or “critical” roles and competencies. As discussed, the focus on pivotal roles often uncovers hidden opportunities that traditional analysis misses.

Business leaders are seldom presented with an analysis of HR programs that is consistent with traditional financial investment models, but these chapters provided a framework to do just that. The chapters showed that investments in enhanced staffing can be analyzed for their impact on profits and discussed how to take into account standard financial considerations such as variable costs, discount rates, and taxes. Whereas every organization is concerned about potential talent shortages and enhancing its position in the “war for talent,” Chapters 8, 9, and 10 showed that savvy organizations go much deeper, to determine where investments in improved staffing will and will not pay off. They do that with much greater sophistication and account for far more than simply whether positions are filled at a reasonable cost. Indeed, if other organizations are managing their staffing processes exclusively in terms of headcount and cost, more sophisticated organizations may well emerge as the victors in the more subtle game of talent management.

Taking HR Development Beyond Training to Learning and Workforce Enhancement

I know that we can deliver training much more cheaply if we just outsource our internal training group and rely on off-the-shelf training products to build the skills we need. We could shut down our corporate university and save millions.

As shown in Chapter 11, “Costs and Benefits of HR Development Programs,” it is very dangerous to assume that all training has equivalent effects and that low-cost training is always better. Like other HR programs, some hidden effects of training are simply not apparent with the traditional accounting approaches. Leaders who fail to understand how training, development, and learning work together, and who fail to understand the factors that enhance their effects, risk investing in too much development where it is not needed and too little where it is desperately needed.

Chapter 11 provided a framework that embeds training within a larger concept of employee development. It showed that organizations must consider not only the development or learning experience, but also whether individuals are sufficiently prepared and ready to develop, and whether they have opportunities to transfer their learning back to the workplace. A significant implication of this model is that the investments that determine the effectiveness of development often extend well beyond the learning or training experience itself. Yet the vast majority of learning and training analyses focuses almost solely on the learning event. The framework also noted that improved work performance is only one outcome of enhanced development. In a world where job applicants increasingly regard development opportunities as a core element of the value proposition (particularly in economically developing regions), organizations that invest prudently in development have the potential for ancillary benefits through recruitment, retention, and reduced turnover.

As the chapter showed, the value of an investment in workforce development depends on the costs of that investment, the resulting quality of the workforce, and the impact of that quality improvement on the pivotal elements of the work. We presented analyses that found relationships (but not causal ones) between training expenditures and subsequent stock performance. We also saw that organizations often focus only on learning or performance as development outcomes, but that investments in workforce development may have important effects on employee attitudes, too.

Finally, Chapter 11 connected the earlier discussions about pivotalness and the value of variations in job performance to estimates of the payoffs from employee development. As discussed in that chapter, with a few simple modifications, the same formulas that enabled us to project the monetary value of staffing allow us to project the monetary value of development. Again, a vital factor to consider is the value of performance variability, what we have called the “pivotalness” of performance in a job or role. Better training is not equally valuable everywhere, and organizations that simply strive to enhance the skills of all employees will fail to optimize their investments. Using the frameworks of Chapter 11, organizations can apply the same rigor and logic to investments in workforce development that they apply to investments in other important resources.

Thus, when business leaders mistakenly focus only on the costs or even the learning outcomes of development, they miss opportunities and risk wasting significant resources. The development framework of Chapter 11 not only helps to estimate costs and learning outcomes more accurately, but it also embeds them in a broader and more appropriate investment framework.

Intangible Does Not Mean “Unmeasurable”

Accounting systems measure important costs, but effective talent decision frameworks go beyond costs to encompass “intangible” investments and value. As the chapters in this book have shown, intangible does not mean “unmeasurable,” even if traditional accounting frameworks frequently overlook these “intangibles.” The first step in improving talent decisions is often just to break through a traditional perception that decisions about talent cannot be systematic because talent measures are so “soft.” Research shows that if managers perceive HR issues as strategic and analytical, they may simply not attend to analytical and numeric analysis. They seem to place HR in a “soft” category of phenomena that are beyond analysis and, therefore, addressable only through opinions, politics, or other less analytical approaches.1

An initial step in effective measurement is to get managers to accept that HR analysis is possible and could be informative. The way to do that is often not to present the most sophisticated analysis right away. Instead, the best approach may be to present relatively simple measures that clearly connect to the mental frameworks that managers are familiar with. As you have seen throughout this book, simply calculating and tracking the costs of turnover or absence, for example, reveals that millions might be saved with even modest reductions in employee turnover and absenteeism. Many organization leaders have told us that such a turnover-cost analysis was their first realization that HR issues could be connected to the tangible economic and accounting outcomes they were familiar with.

No one would suggest that measuring only the cost of turnover is sufficient for good decision making. As the frameworks in earlier chapters show, overzealous attempts to cut turnover or absence costs can lead to compromises in workforce quality or flexibility that have negative effects that far outweigh the cost savings. However, the change process toward more enlightened and logical decisions may require starting with costs before presenting leaders with more complete (and complex) analyses. An initial analysis that shows simple reductions in costs may create the sort of awareness among leaders that the same analytical logic used for financial, technological, and marketing investments can apply to human resources. Returning to the framework that we introduced in Chapter 1, HR measures in all three anchor points (efficiency, effectiveness, and impact) are useful. From a change-management perspective, efficiency measures may be the appropriate starting point to get broad acceptance of the idea of building measures that include effectiveness and impact.

The belief that something can’t be measured is simply no excuse for avoiding logical analysis. As you have seen, it is possible to measure many aspects of talent that traditional systems seldom recognize. For example, there are several ways to measure the value of differences in performance, changes in employee attitudes, and the responses of employees to investments in employee health and welfare. Organizational leaders remain mostly naïve to these opportunities and, therefore, naïve to the significant opportunities they provide for enhancing their decisions. Even when perfect measures are unavailable, you have seen that solid logic can enhance decisions, using sensitivity analysis, simulation, and risk assessment to make up for measurement imperfections, just as these tools are used in other areas of management.

The HC BRidge Framework as a Meta Model

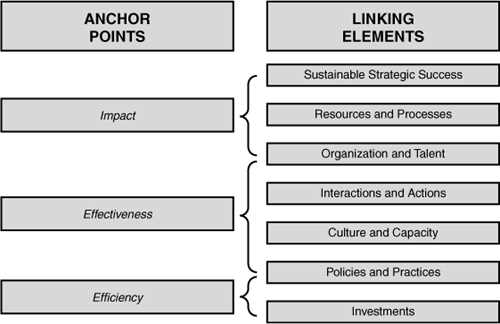

Figure 12-1 shows the HC BRidge framework. In Chapter 1, we introduced the anchor points of this framework: efficiency, effectiveness, and impact. Here we show the linking elements between HR investments and sustainable strategic success. We have not attempted to define measurements for every linking element, and more detail on the linking elements can be found elsewhere.2 We have suggested that, when measuring the effects of HR investments, organization leaders should keep all three anchor points in mind.

Figure 12-1. HC BRidge framework.

Proceeding from the bottom-right side of Figure 12-1, we note that investments and policies and practices are perhaps the most prominent and tangible elements of the measurement frameworks we have described here. The chapters provided detailed frameworks for identifying both the tangible and intangible costs comprising HR investments, and they explained how to measure the frequency and use of HR policies and practices. Relying on those frameworks, HR leaders can estimate more accurately the full costs of programs such as training, health care, testing, recruiting, and communication, as well as the activity levels and use of such programs by employees and managers.

An important facet of our treatment of each HR program was to provide an overall logic model that showed the required conditions that must be achieved for the effects of the programs to offset their costs. These are “necessary and sufficient” conditions.3 They comprise not only the elements that are necessary, but all the elements that are sufficient to achieve or explain program success. These conditions not only guide measurement, but they also become powerful frameworks for more sophisticated logical discussions about where and how HR programs work. Consider the supply-chain framework for staffing and the logical elements of the staffing-utility model. Chapters 8, 9, and 10 showed that, by combining powerful statistical assumptions with the simple concepts of cost, quantity, and quality, we can develop frameworks that predict when enhanced recruitment, selection, and retention will pay off, and how the three elements interact. More applicants are not always better, just as more valid testing and higher retention rates are not always optimal. The “necessary and sufficient conditions” depicted in the logic models in each chapter of the book allow leaders to go beyond simply recognizing the idea of optimization and instead actually strive to achieve it.

Culture emerged in a more subtle way. Looking back, virtually every chapter recognized the importance of a prominent “resource”—leadership support and engagement by key managers and supervisors—that is essential for success. This hidden resource is frequently the most vital requirement, and we have seen examples of its importance in areas as diverse as employee welfare, selection, and training. In addition, we have seen the importance of values, norms, and beliefs in driving sustained progress when the outcomes in question require long-term commitments, as in the case of employee development, health improvement, and better work-life fit. We have seen that although it is important to understand and track specific program investments and outcomes, contextual factors often are key determinants of the overall effectiveness of any given program.

Capacity has figured prominently in the frameworks we have described. Measuring the payoff of HR investments almost always includes assessing the effect of programs on the skill, knowledge, and capability of those who receive them. We have shown that knowledge and learning not only are measurable, but also often provide essential clues to understanding the mechanisms through which such programs eventually affect organizational performance. Moreover, we showed how to measure engagement and commitment, which represent important proxies for employee motivation. Measuring the combination of capability and motivation makes it possible to estimate the immediate return on investment (ROI) from HR programs using logic very similar to the ROI calculations that are so familiar in the context of other vital organizational investments. Indeed, as we have seen, cost-effectiveness analysis frequently provides valuable insights even when outcomes are not translated into monetary values. It is often quite valuable to estimate the cost of a particular increase in knowledge, learning, or engagement, particularly when comparing two or more programs designed to affect the same outcomes.

Actions and interactions have figured prominently because performance is usually observed through the specific actions or work behaviors of employees and their interactions both within and outside the organization. As Chapter 9 showed, deeply analyzing such performance elements often reveals unseen opportunities to create value by improving employee performance. The fundamental distinction between the average value of performance, or its “importance,” and the value of performance differences, or pivotalness, is the key to understanding where improving investments in performance will pay off. We saw that traditional job descriptions often obscure pivot points, but that estimating the dollar value of performance differences often reveals pivot points and their associated opportunities. Once again, virtually all leaders recognize the principle of investing where there are large opportunities for gains. Chapter 9 showed how to find them, by considering the actions and interactions that make the biggest difference in key performance outcomes.

Resources and processes in the HC BRidge framework provide the connection points between the observable actions and interactions typically measured in performance assessment, and their effects on the sustainable strategic success of the organization. This kind of deep strategy analysis is a topic beyond the scope of this book,4 but the importance of resources and processes in evaluating the effects of improved talent was still apparent. Often measures of the value of performance relied on an understanding of how performance affected processes such as sales or production.

As we have seen, although enhanced employee performance, engagement, health, knowledge, retention, and attendance are laudable goals, they are not uniformly valuable. We have seen how important it is to ask questions such as “learning for what purpose?” Often the answers require integrating the measurement of HR investments with strategy and planning processes outside the HR function. More precisely measuring the efficiency and effectiveness elements of such programs, which has been the focus of this book, provides a powerful platform for then engaging the question of how these outcomes really affect the business.

Lighting the LAMP of Organization Change

“Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.” This quote, often attributed to Albert Einstein, reflects some important conclusions and caveats as you begin to apply the frameworks we have described here. First, it is certainly true that we can’t measure everything about talent and HR program effects. Many important elements of such investments remain relatively obscure and cannot be translated precisely into numbers. In particular, they remain outside the domain of traditional business measurement systems. That said, it is also apparent that the frequent failure to make systematic decisions about HR and talent investments is seldom due to the lack of measures. Indeed, advances in technology make it ever more possible to measure vital costs and effects that were once out of reach. Consider the ease with which data from organizational processes, such as supply chains and customer relationship management systems, can be accessed as those processes become more web enabled. Relating HR practices to these processes will be easier in the future. It is now feasible to connect customer reactions to particular call center or retail encounters with specific employees. Inexpensive and rapidly accessible data storage systems make it possible to archive information about employees at the time they are hired or promoted, and to use that information to determine what factors might be associated with their later success. Indeed, it is now quite feasible to evaluate business leaders on the accuracy and success of their decisions in hiring, promotion, layoffs, and performance assessment.

However, that brings us to perhaps the core dilemma facing future talent-measurement systems: Not everything that can be counted really counts. Some of the things that are easily measured may not be that valuable to decision makers. Information overload is a very real danger without logical frameworks that are capable of guiding leaders to the key relationships and measures that matter most to better decisions. That’s why in this book we have emphasized logic and analytics over simply lists of measures or examples of scorecards. The measurement examples we have presented are meant to inspire and motivate future leaders to see beyond the limits of traditional data systems, but their more important purpose is to illustrate the logic of decision-based measurement. Replicating a particular cost calculation, or implementing a particular measure of engagement, is not the point. What matters is that you use these examples as templates and then develop the most valuable measures for your particular strategic and business situation, while at the same time considering the capacities of your measurement systems.

It is important to avoid the temptation to fixate only on the places where measures exist today. Even imperfect measures can prove extremely valuable if they illuminate vital factors that affect the outcomes of decisions. Logic and analysis are the tools that help take even imperfect measures and create tangible decision value.

In the end, the true test of talent and HR measurement is not its elegance, nor even its acceptance and use by members of the HR profession. These are important factors, but they are merely the intermediate steps to the larger goal: building more effective organizations by making better decisions about talent. We hope that this book will become one important tool in your journey to that important goal.

References

1. Johns, G., “Constraints on the Adoption of Psychology-Based Personnel Practices: Lessons from Organizational Innovation,” Personnel Psychology 46 (1993): 569–592.

2. Boudreau, J. W., and P. M. Ramstad, Beyond HR: The New Science of Human Capital (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2007).

4. Strategy-analysis frameworks are covered in more detail in Boudreau and Ramstad (2007) and, more generally, in classic strategy works that are cited there.