Empowered

MAYBE YOU’VE HEARD ABOUT THE musician Dave Carroll and his experience as a United Air Lines customer. He was so incensed that the company rejected his damage claim after its baggage handlers broke his guitar that he made a catchy YouTube video, “United Breaks Guitars.” Eight million people have already viewed this decidedly negative take on the United brand.

Carroll’s reaction is hardly unique. The popular mommy blogger Heather Armstrong was so upset over the failure of her Maytag washer and the company’s ensuing service missteps that, using her mobile phone, she told her million-plus followers on Twitter they should never buy a Maytag. Greenpeace supporters barraged Nestlé’s Facebook page with complaints about how the company’s sourcing policies lead to environmental damage. The list of examples is endless, because these days anyone with a smartphone or a computer can instantly inflict lasting brand damage.

But it’s not just cranky customers who can use readily available, powerful, hyperconnected technologies to make an impact. Employees can, too. Mark Betka and Tim Receveur, of the U.S. State Department, used off-the-shelf software called Adobe Connect to create Co.Nx, a public diplomacy outreach project that presents webchats with U.S. government officials, businesspeople, and others. The webchats now have international audiences in the tens of thousands and more than 100,000 Facebook fans. At Black & Decker, Rob Sharpe uses homemade online video for sales training, just as Dave Carroll used it to lash out at United. Paul Vienick, in charge of product development for E*Trade, made E*Trade Mobile Pro possible—he used mobile to serve customers and build loyalty, just as Heather Armstrong used it to attack Maytag.

You can build a strategy around empowering employees to solve customers’ problems—but it will challenge your organization from the inside. Freeing employees to experiment with new technologies, to make high-profile decisions on the fly, to build systems that customers see, and to effectively speak for the organization in public is not something most corporations or government agencies are accustomed to doing.

They may be concerned, for example, about how employees will use the technology. After all, part of Nestlé’s problem with Facebook was the clumsy response of its own employees to the Greenpeace attack. But in this age of smartphones and broadband, employees can’t be blocked from doing inappropriate things. It would not have been possible to stop the Domino’s employees who posted a video on YouTube of themselves pretending to perform unsanitary acts on customers’ pizzas.

Far better than trying to prevent such activity is to acknowledge that your employees have technology power. Then you can set policy, train them in permissible communications and activities, and harness their creativity as a strategic force to power your company. Armed with technology, your employees can build solutions at the speed of today’s connected customers. They’re ready to do so. But if you’re like most managers, your company isn’t yet set up to make this activity possible. It could be. It could behave like Best Buy.

Best Buy Empowers Its Staff

Best Buy is just as susceptible to online customer complaints as any other company, but because it’s run differently, it can respond differently. A good example is Twelpforce. More than 2,500 Best Buy employees have signed up for this system, which enables them to see Best Buy–related problems that customers have aired on Twitter and respond to them. Twelpforce includes customer service staff, in-store sales associates (called Blue Shirts), and Geek Squad, the service reps who make house calls for technical assistance.

Here’s an example of how Twelpforce works: Earlier this year Josh Korin bought an iPhone, along with an insurance plan, from Best Buy in Chicago. When the iPhone stopped working, the in-store staff offered him a BlackBerry as a loaner replacement. That wasn’t what he felt he deserved after buying the insurance plan, so he began tweeting about his disappointment. Even though it was over a weekend, a customer service rep, Coral Biegler, responded quickly on Twitter. By the next day she had arranged for him to get a replacement iPhone. Korin changed his tune and began tweeting about how great Best Buy’s service was. So did his wife, who has more than 3,000 Twitter followers.

Twelpforce exists because Best Buy empowers its employees to come up with technological solutions. Gary Koelling, a social media expert in Best Buy’s marketing group, helped originate the idea. Ben Hedrington, a technology staffer in the e-commerce group, figured out in a week of evenings how to tap Google’s cloud computing service to build a Twitter system serving multiple employees. John Bernier, a marketing manager, took charge of the project and triumphed over legal obstacles, including labor laws.

Best Buy’s leaders support technological innovation regardless of where in the organization it comes from. Barry Judge, the company’s CMO, has made it a priority to identify and encourage new ideas like Twelpforce. “We’re almost always in a half-baked mode” when it comes to ideas, Judge says. “Half-baked ideas allow people [both internally and externally] to give you feedback.” Judge’s marketing department is always learning. “If you are not curious, you won’t last long in marketing,” he says. “You have to have some failures to see that.”

The results of this attitude are visible throughout Best Buy’s marketing. For example, Judge posts the company’s TV commercials on his blog before they start airing. In one case, commenters from outside the company complained about a lack of sensitivity in a commercial describing how a Blue Shirt helped a customer in the armed forces. The commercial never aired. Best Buy has also taken the innovative step of opening up the programming interfaces to BestBuy.com, allowing other websites to alert people of price changes, for example. All these activities were developed by marketing staffers. All involved risk. And all went forward.

The HERO Compact

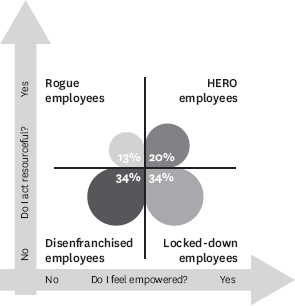

Because of the image it evokes, we use the term HERO (“highly empowered and resourceful operative”) for people who innovate with technology inside a company. HEROes exist because technologies like Twitter, online communities, cloud computing, and online video are so easy to master and so cheap to set up. Employees, especially in marketing, sales, and customer service, see customers’ problems and use these technologies to solve them. Moving forward with their solutions creates challenges for three groups: the HEROes themselves, management, and IT.

Most companies aren’t set up to harness technological innovation that comes from outside IT. Their IT departments can’t launch and run these sorts of projects—they’re too far from customers and typically lack the budget and staff. Even so, they’re uncomfortable (often with good reason) when marketers and others move forward with technology. As for managers, both senior and midlevel, they want to encourage innovation but worry about the risks associated with these projects. And the HEROes have trouble executing their plans at scale in the absence of consistent support.

In most companies, cultural resistance to empowering employees to use technology is systemwide. Keeping technology locked down and under the IT department’s control seems like the safe thing to do. It limits risk and prevents chaos. This traditional approach would be fine if not for the actions of all those empowered customers. Companies have to respond to customers’ escalating power. Their employees are ready to do so. The challenge is to encourage HERO-driven innovation without generating chaos.

A crucial part of the solution is what we call the HERO Compact—an agreement among the three groups to work together to manage technological innovation. Under the compact:

- HEROes agree to innovate within a safe framework. The employees who come up with these projects must work within business structures. They must respond to support from management and IT by innovating in directions that align with corporate strategy and by observing security, legal, and other corporate policies. Having succeeded with a project, a HERO is responsible for spreading newly won knowledge to others in the organization who might benefit from it.

- Managers agree to encourage innovation and manage risk. Managers must communicate their openness to employee innovation, not just with words but by recognizing examples publicly and not punishing failures. To ensure that HERO activity is productive, managers must also clearly and regularly communicate strategic goals. And they must work with IT to understand and deal with the risks associated with HERO projects, modifying them or even shutting them down if the legal or regulatory risks are out of line with any expected benefit.

- IT agrees to support and scale up HERO projects. IT needs to advise HEROes and keep them safe. At PTC, a Massachusetts-based supplier of computer-aided design and product life-cycle management software, after the marketing department came up with the idea for a customer community and provided funding, IT played a key role in evaluating technology vendors for the community. IT must assess and mitigate risk and then give managers the tools to understand the risks in the context of the business benefits. It must also recognize when HERO projects have become strategic and help scale them up.

None of this can succeed unless the company and its technology policies are ready. (See the sidebar “Is Your Company Ready for Empowered Employees?”) But when it does work, HERO-driven, incremental innovation wells up from every customer-facing department. This radically improves the agility with which companies can address the needs of their empowered customers. Let’s look at some more examples.

Video Training at Black & Decker

Rob Sharpe is the director of sales training at Black & Decker (now part of Stanley Black & Decker). The company’s hundreds of sales staffers must explain and sell a multitude of complex products to retailers as huge as Home Depot and as small as mom-and-pop hardware stores. The market is highly competitive. Although the company had been doing effective sales training using PowerPoint and an in-house learning system, Sharpe conceived of a new approach after taking a look at YouTube.

As a pilot project, Sharpe gave out $150, simple-to-use Flip video cameras and free video editing software to several dozen salespeople in the training program. His reasoning: “I’m a visual learner; a lot of these tool guys are visual learners.” One of his trainees, back out in the field, sent in a video that showed the weaknesses of a competitor’s product. Both the training staff and other salespeople immediately “got it,” seeing how effective video could be for Black & Decker sales.

More video started pouring in. Salespeople began documenting challenges, product features, and effective sales solutions. Video cameras became a standard part of sales training. According to Sharpe, “Now we get 15 to 20 videos a month—how power tools are used on job sites, feedback on the tools. And the content is already completely edited,” ready for viewing.

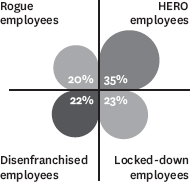

| Technology products and services workers | |

| Further analysis reveals patterns by industry. The technology products and services industry, with 37% of its workers in the HERO quadrant, is far more likely than other industries to generate employee-created innovations. (The industries with the lowest proportion of information workers in the HERO quadrant are retail, government, health care, and education.) |  |

| Marketing and sales staff | |

| We also analyzed workers by job description. Among those in marketing and sales (excluding retail sales workers), 35% are HEROes, meaning that they have great potential for creative innovation—a fact we saw reflected in the many new technology and social applications coming out of marketing departments in the companies we researched. |  |

“I will not let people in this department create a 45-minute course again,” Sharpe says. “It’s not what the staff need or what they want. Speed to execution is just as important. The training staff can spend a half hour with the product, come up with our own opinions and competitive analysis, and send [a video] out the next day with an assessment.”

The most popular videos are viewed by more than half of Black & Decker’s sales force. Training that used to take two weeks now takes one. New staff members spend 15 hours online before even coming to the training center. Senior management, corporate marketing, and public relations people review the collection for useful bits of content and motivational nuggets.

Black & Decker’s IT department was reluctant at first, citing concerns about security and space on the server. Now it’s an enthusiastic supporter. And Sharpe’s manager, Les Ireland, then Black & Decker’s president of commercial operations in North America, supported his efforts.

“The concept of getting our teams involved in delivering ‘real world’ content was a powerful idea,” Ireland says. He also likes the increase in speed and agility: “How quickly we can execute a new technology in order to capture the productivity across our commercial team is always a critical question.” Black & Decker’s success with video illustrates a broader point: Regardless of where the HERO projects we’ve studied began, they grew fastest when management and IT were on board.

Social Media Marketing at Vail Resorts

Vail Resorts operates multiple properties, including five major ski resorts. The company found that its traditional advertising strategy—space in Ski magazine and other long-lead publications—was becoming ineffective; customers had begun booking ski vacations only weeks or days in advance. Vail needed to create pitches tailored to what was happening at the moment—snowfall, competitors’ promotions, local events.

Vail’s CEO, Rob Katz, decided to remake his marketing plan, with a focus on short-lead media such as newspapers and internet sites. He also decided to embrace Facebook and Twitter, where many skiers now get their information. “We needed to be a leader in [the social] space, rather than battle the trend of where our customers are going,” he says.

Katz hired Mike Slone, an interactive development veteran, to head up social engagement in the new marketing strategy. Slone manages five staffers at Vail’s corporate headquarters who respond to tweets, blogs, and other social-media inquiries. He also works to involve other staff members, including the heads of online marketing at each of the company’s five mountain resorts. One of their tasks is creating videos of activity on the slopes and posting them as soon as possible. In essence, Vail uses customers themselves to generate a sense of fun, exciting and helping to recruit other customers.

Katz sends signals from the top showing the level of creativity and responsiveness to customers that he’d like to see. He himself tweets, as @rickysridge. When a customer named Bob Lefsetz tweeted about a problem he’d had signing up for a meal pass, Katz responded and made sure that one of his staffers got Lefsetz what he was looking for. It turned out that Lefsetz is an acerbic and popular blogger in the music industry who has nearly 13,000 Twitter followers. After this exchange they read about how great Vail is rather than getting a “United Breaks Guitars”–style rant.

Katz and the other HERO-friendly managers we’ve surveyed have a common attitude toward their staffs and employee innovation. First, they clearly communicate corporate priorities (such as the shift to short-lead media). Second, they encourage experimentation—within the bounds of maintaining brand image and avoiding identifiable security risks. Third, they tolerate failure as long as it leads to learning. And fourth, they create systems and structures within their companies that bust silos, which enables HEROes to share their learning and connect with others facing similar challenges.

IT Prodding and Support at Aflac

Gerald Shields, the chief information officer of the supplemental insurance provider Aflac, has plenty to do. He manages 600 IT professionals and a $135 million budget. His people operate the systems that keep Aflac’s transactions flowing and the networks that bind the company together. But he finds time to prod the rest of the company into coming up with technology projects for customer service.

Shields educated his direct reports and Paul Amos, Aflac’s president, about social technologies. Then he went to work on Jeff Charney, the chief marketing officer. The combination of management support and IT backing proved powerful. Amos and Charney convened managers from all over the company for a workshop on social-technology opportunities. Several cross-functional groups left the workshop charged with creating actionable plans for social applications. Shields and Charney then selected the two most promising ideas that emerged: an online community for Aflac’s 80,000 independent sales associates, and one for 200,000 billing and payroll administrators at customer companies.

The independent sales associates’ community is called The Buzz. Aflac’s field salespeople close thousands of deals a month; when they can connect with one another and with their service and marketing support teams, they learn rapidly. Each month 2,800 sales associates visit The Buzz.

Duck Pond is the community that serves billing and payroll administrators. These people didn’t make the decision to buy Aflac, but they’re a key group in getting its benefits delivered effectively. They also value connecting to people in similar jobs, because they typically work in human resources or finance, with few internal peers. Duck Pond was created not only to share information about Aflac but also to help the administrators get support from the company and from their peers on all sorts of issues, not just those related to insurance. As Shields puts it, “We don’t want you to think of Aflac as just a supplemental insurance company. We want you to say, ‘Wait a minute—I’m on Duck Pond all the time.’”

Too often we’ve seen companies launch social applications without IT support and hit a scaling or integration or security wall. Gerald Shields stands out for stimulating innovation from product, marketing, and sales support groups even though he won’t own the results. His initiative got management on board, and management benefited as the innovation spread throughout the company. And Shields can steer HERO activity in what he believes will be productive technological directions.

HERO-Driven Innovation for B2B

The dynamics that lead to HERO-driven innovation depend on customers’ and employees’ using powerful, readily accessible technology. They don’t depend on the industry those customers are in or on whether a company sells to businesses or consumers.

It’s a commonly held fallacy that consumers use social applications more than businesses do. But our surveys of business buyers show that 95% use social technologies and 76% use them for work—a higher level of participation than among consumers. Mobile technologies in particular are important, as demonstrated by the ubiquity of smartphones for business communication.

PTC, the software supplier, went forward with an online social community because surveys of its business customers showed overwhelming support for such outreach. Black & Decker’s sales staff sells to buyers at retail chains, and Aflac’s customers are businesses as well. HEROes can innovate, IT can support their innovation, and managers can reap the rewards regardless of whether a company sells to consumers or to businesses.

Building a HERO-Powered Business

Companies that want to encourage this sort of innovation should embrace the HERO Compact. But even when they do, it takes a while for corporate cultures to change. In the meantime, managers throughout the organization can move forward on their own, stimulating and rewarding HERO activity.

If you are a manager or other employee who has come up with a solution—that is, if you’re a potential HERO—the first step is to evaluate your idea: How many different departments will need a say? How difficult to deploy is the technology? How big a budget will you need? Then look not only at the value you will create, but also at how you can prove that value, in decreased costs, increased revenues, additional leads, or other metrics that matter to the business. Unless you’ve assessed both the effort and the value, you can’t really know whether your project is worth doing—or whether you’ll be able to convince management that it’s worth doing.

We also recommend looking for similar projects in the enterprise. Look for people who are using the same technologies you’re using (say, online communities and Twitter), but also for people facing the same challenges (such as working with PR and customer service). You’ll learn a lot from those who have trodden the same ground and faced the same obstacles. Build an internal community to find and collaborate with these people.

For higher-level managers, the key is not just encouragement but visibility. Simply urging people to be more creative doesn’t work. Instead, identify the kinds of solutions you’re looking for—outside as well as inside your company. At General Mills, for example, marketing leaders hold monthly department meetings where they highlight creative strategies used by other brands and industries.

You might also want to review your hiring practices. Find people who are conversant with online social networks, online video, web services, and social applications. Their skills will help raise the level of innovation in your department.

If you’re in IT, you don’t have to be the CIO to behave like Gerald Shields. Reach out to marketing, sales, and other customer-facing departments—and go out to meet customers. IT’s reputation for standoffishness can dissolve after a few face-to-face meetings. Concentrate a little more on saying “Yes, and here’s how,” and less on saying “No, that’s unsafe/too expensive/not possible.” The payoff is in becoming more plugged in, more relevant, and more valuable.

What Is Your Company’s Future?

With all this powerful, inexpensive, easily accessible technology available, every manager has a choice. You can fight your employees’ natural impulse to connect with customers and build solutions. You can lock down the systems, ask IT to block the sites, and ensure that no unauthorized technology-driven activity takes place. Given smartphones, countless free web services, and people who own their own laptops, you’re unlikely to succeed. But you will spend a lot of energy proving to your employees that you don’t trust them and you don’t want them to innovate. And you’ll be defenseless when the next Dave Carroll or Heather Armstrong comes after your brand.

Or you can recognize that your employees are the solution to customers’ problems and find ways to stimulate, harness, and channel their innovations. You can acknowledge their activity and manage the risks to keep them and your company safe as well as responsive.

Our research shows that technological innovation can now come from anywhere in a company. What makes the difference is whether the company has organized itself so that its creative people can become HEROes.

JOSH BERNOFF is the senior vice president for idea development at Forrester Research and a coauthor of Groundswell: Winning in a World Transformed by Social Technologies (Harvard Business Review Press, 2008). TED SCHADLER is a principal analyst at Forrester Research. Portions of this article were adapted from Empowered (Harvard Business Review Press, 2010).

Originally published in July 2010. Reprint R1007H