Finding Your Next Core Business

IT IS A WONDER HOW MANY management teams fail to exploit, or even perceive, the full potential of the basic businesses they are in. Company after company prematurely abandons its core in the pursuit of some hot market or sexy new idea, only to see the error of its ways—often when it’s too late to reverse course. Bausch & Lomb is a classic example. Its eagerness to move beyond contact lenses took it into dental products, skin care, and even hearing aids in the 1990s. Today B&L has divested itself of all those businesses at a loss, and is scrambling in the category it once dominated (where Johnson & Johnson now leads). And yet it’s also true that no core endures forever. Sticking with an eroding core for too long, as Polaroid did, can be just as devastating. Both these companies were once darlings of Wall Street, each with an intelligent management team and a formerly dominant core. And in a sense, they made the same mistake: They misjudged the point their core business had reached in its life cycle and whether it was time to stay focused, expand, or move on.

How do you know when your core needs to change in some fundamental way? And how do you determine what the new core should be? These are the questions that have driven my conversations with senior managers and the efforts of my research team over the past three years. What we’ve discovered is that it is possible to measure the vitality remaining in a business’s core—to see whether that core is truly exhausted or still has legs. We’ve also concluded from an in-depth study of companies that have redefined their cores (including Apple, IBM, De Beers, PerkinElmer, and 21 others) that there is a right way to go about reinvention. The surest route is not to venture far afield but to mine new value close to home; assets already in hand but peripheral to the core offer up the richest new cores.

This article discusses both these findings. It identifies the warning signs that a business is losing its potency and offers a way to diagnose the strength remaining in its core. It recounts the efforts of managers in a variety of settings who saw the writing on the wall and succeeded in transforming their companies. And, based on these and other cases, it maps the likely spots in a business where the makings of a new core might be found.

When It’s Time for Deep Strategic Change

Not every company that falls on hard times needs to rethink its core strategy. On the contrary, declining performance in what was a thriving business can usually be chalked up to an execution shortfall. But when a strategy does turn out to be exhausted, it’s generally for one of three reasons.

The first has to do with profit pools—the places along the total value chain of an industry where attractive profits are earned. If your company is targeting a shrinking or shifting profit pool, improving your ability to execute can accomplish only so much. Consider the position of Apple, whose share of the market for personal computers plummeted from 9% in 1995 to less than 3% in 2005. But more to the point, the entire profit pool in PCs steadily contracted during those years. If Apple had not moved its business toward digital music, its prospects might not look very bright. General Dynamics was in a similar situation in the 1990s, when defense spending declined sharply. To avoid being stranded by the receding profit pool, it sold off many of its units and redefined the company around just three core businesses where it held substantial advantages: submarines, electronics, and information systems.

The second reason is inherently inferior economics. These often come to light when a new competitor enters the field unburdened by structures and costs that an older company cannot readily shake off. General Motors saw this in competition with Toyota, just as Compaq did with Dell. Other well-known examples include Kmart (vis-à-vis Wal-Mart) and Xerox (vis-à-vis Canon). Occasionally a company sees the clouds gathering and is able to respond effectively. The Port of Singapore Authority (now PSA International), for example, fought off threats from Malaysia and other upstart competitors by slashing costs and identifying new ways to add value for customers. But sometimes the economics are driven by laws or entrenched arrangements that a company cannot change.

The third reason to rethink a core strategy is a growth formula that cannot be sustained. A manufacturer of a specialized consumer product—cell phones, say—might find its growth stalling as the market reaches saturation or competitors replicate its once unique source of differentiation. Or a retailer like Home Depot might see its growth slow as competitors like Lowe’s catch up. A company that has prospered by simply reproducing its business model may run out of new territory to conquer: Think of the difficulties Wal-Mart has encountered as the cost-benefit ratio of further expansion shifts unfavorably. The core business of a mining company might expire as its mines become depleted. In all such circumstances, finding a new formula for growth depends on finding a new core.

For most of the companies my team and I studied, recognition that the core business had faltered came very late. The optical instruments maker PerkinElmer, the diamond merchant De Beers, the audio equipment manufacturer Harman International—these were all companies in deep crisis when they began their redefinition. Is it inevitable that companies will be blindsided in this way? Or can a management team learn to see early signs that its core strategy is losing relevance?

With that possibility in mind, it would seem reasonable to periodically assess the fundamental vitality of your business. The exhibit “Evaluate your core business” offers a tool for doing so. Its first question looks at the core in terms of the customers it serves. How profitable are they—and how loyal? Arriving at the answers can be difficult, but no undertaking is more worthwhile; strategy goes nowhere unless it begins with the customer. The second question probes your company’s key sources of differentiation and asks whether they are strengthening or eroding. The third focuses on your industry’s profit pools, a perspective that is often neglected in the quest for revenue and market share growth. Where are the best profits to be found? Who earns them now? How might that change? The fourth examines your company’s capabilities—a topic we shall soon turn to—and the fifth assesses your organization’s culture and readiness to change.

Evaluate your core business

Five broad questions can help you determine when it is time to redefine your company’s core business. For most companies, the answers to these questions can be found by examining the categories listed next to each one.

If the answers reveal that large shifts are about to take place in two or more of these five areas, your company is heading into turbulence; you need to reexamine the fundamentals of your core strategy and even the core itself.

At the least, managers who go through this exercise tend to spot areas of weakness to be shored up. More dramatically, they may save a business from going under. Note, however, that no scoring system is attached to this diagnostic tool—there is no clearly defined point at which a prescription for strategic redefinition is issued. That would lend false precision to what must be a judgment call by a seasoned management team. The value of the exercise is to ensure that the right questions are taken into account and, by being asked consistently over time, highlight changes that may constitute growing threats to a company’s core.

Recognizing the Makings of a New Core

Management teams react in different ways when they reach the conclusion that a core business is under severe threat. Some decide to defend the status quo. Others want to transform their companies all at once through a big merger. Some leap into a hot new market. Such strategies are inordinately risky. (Our analysis suggests that the odds of success are less than one in ten for the first two strategies, and only about one in seven for the third.) The companies we found to be most successful in remaking themselves proceeded in a way that left less to chance. Consider, for example, the transformation of the Swedish company Dometic.

Dometic’s roots go back to 1922, when two engineering students named Carl Munters and Baltzar von Platen applied what was known as absorption technology to refrigeration. Whereas most household refrigerators use compressors driven by electric motors to generate cold, their refrigerator had no moving parts and no need for electricity; only a source of heat, as simple as a propane tank, was required. So the absorption refrigerator is particularly useful in places like boats and recreational vehicles, where electric current is hard to come by. In 1925 AB Electrolux acquired the patent rights. The division responsible for absorption refrigerators later became the independent Dometic Group.

By 1973 Dometic was still a small company, with revenues of just 80 million kronor (about U.S. $16.9 million). Worse, it was losing money. Then Sven Stork, an executive charged with fixing the ailing Electrolux product line, began to breathe new life into the business. Stork, who went on to become president and CEO of the company, moved aggressively into the hotel minibar market, where the absorption refrigerator’s silent operation had a real advantage over conventional technology. Fueled by those sales, Dometic grew and was able to acquire some of its competitors.

The real breakthrough came when Stork’s team focused more closely on the RV market, which was just then beginning to explode. The point wasn’t to sell more refrigerators to the RV segment; the company’s market share within that segment was already nearly 100%. Rather, it was to add other products to the Dometic line, such as air-conditioning, automated awnings, generators, and systems for cooking, lighting, sanitation, and water purification. As Stork explains, “We decided to make the RV into something that you could really live in. The idea was obvious to people who knew the customers, yet it took a while to convince the manufacturers and especially the rest of our own organization.” These moves fundamentally shifted the company’s core. Dometic was no longer about absorption refrigeration: It was about RV interior systems and the formidable channel power gained by selling all its products through the same dealers and installers. That channel power allowed Dometic to pull off a move that enhanced its cost structure dramatically. The company streamlined its go-to-market approach in the United States by skipping a distribution layer that had always existed and approaching RV dealers directly. “We prepared for the risks like a military operation,” Stork recalls, “and it was a fantastic hit. We were the only company large enough to pull this off. It let us kill off competitors faster than they could come out of the bushes.” By 2005 Dometic had grown to KR 7.3 billion, or roughly U.S. $1.2 billion. No longer part of Electrolux (the private equity firm EQT bought it in 2001 and sold it to the investment firm BC Partners a few years later), the company was highly profitable and commanded 75% of the world market share for RV interior systems.

Dometic’s story of growth and redefinition is especially instructive because it features all the elements we’ve seen repeatedly across the successful core-redefining companies we’ve studied. These are: (1) gradualism during transformation, (2) the discovery and use of hidden assets, (3) underlying leadership economics central to the strategy, and (4) a move from one repeatable formula that is unique to the company to another. “Gradualism” refers to the fact that Dometic never made anything like a “bet the company” move—often tempting when a business is on the ropes, but almost always a loser’s game. As in the other cases of strategic renewal we studied, it redefined its core business by shifting its center of gravity along an existing vector of growth. To do this, it relied on hidden assets—resources or capabilities that it had not yet capitalized on. In Dometic’s case, the treasure was its understanding of and access to customers in the RV market.

Leadership economics is a hallmark of almost every great strategy; when we see a situation in which the rich get richer, this is the phenomenon at work. Consider that most industries have more than six competitors, but usually more than 75% of the profit pool is captured by the top two. Of those two, the one with the greatest market power typically captures 70% of total profits and 75% of profits above the cost of capital. When Dometic focused on a defined market where it could stake out a leadership position, enormous financial benefits followed.

Its new growth formula offers the same kind of repeatability the old one did. Recall that Dometic’s first focus was on applications for absorption refrigeration, which it pursued product by product, one of which was for RVs. The new formula angled off into a sequence of interior components for the RV customer base. Recently, as RV sales have slowed, Dometic has moved into interior systems for “live-in” vehicles in general, including boats and long-haul trucks.

Where Assets Hide

The importance of a company’s overlooked, undervalued, or underutilized assets to its strategic regeneration cannot be overstated. In 21 of the 25 companies we examined, a hidden asset was the centerpiece of the new strategy.

Some of their stories are well known. A few years ago, a struggling Apple realized that its flair for software, user-friendly product design, and imaginative marketing could be applied to more than just computers—in particular, to a little device for listening to music. Today Apple’s iPod-based music business accounts for nearly 50% of the company’s revenues and 40% of profits—a new core. IBM’s Global Services Group was once a tiny services and network-operations unit, not even a stand-alone business within IBM. By 2001 it was larger than all of IBM’s hardware business and accounted for roughly two-thirds of the company’s market value.

Why would well-established companies even have hidden assets? Shouldn’t those assets have been put to work or disposed of long since? Actually, large, complex organizations always acquire more skills, capabilities, and business platforms than they can focus on at any one time. Some are necessarily neglected—and once they have been neglected for a while, a company’s leaders often continue to ignore them or discount their value. But then something happens: Market conditions change, or perhaps the company acquires new capabilities that complement its forgotten ones. Suddenly the ugly ducklings in the backyard begin to look like swans in training.

The real question, then, is how to open management’s eyes to the hidden assets in its midst. One way is to identify the richest hunting grounds. Our research suggests that hidden assets tend to fall into three categories: undervalued business platforms, untapped insights into customers, and underexploited capabilities. The exhibit “Where does your future lie?” details the types of assets we’ve seen exploited in each category. For a better understanding of how these assets came to light, let’s look at some individual examples.

Undervalued Business Platforms

PerkinElmer was once the market leader in optical electronics for analytical instruments, such as spectrophotometers and gas chromatographs. Its optical capabilities were so strong that the company was chosen to manufacture the Hubble Space Telescope’s mirrors and sighting equipment for NASA. Yet by 1993 PerkinElmer, its core product lines under attack by lower-cost and more innovative competitors, had stalled out. Revenues were stuck at $1.2 billion, exactly where they had been ten years earlier, and the market value of the company had eroded along with its earnings; the bottom line showed a loss of $83 million in 1993. In 1995 the board hired a new CEO, Tony White, to renew the company’s strategy and performance and, if necessary, to completely redefine its core business.

Where does your future lie?

If the core of your business is nearing depletion, the temptation may be great to venture dramatically away from it—to rely on a major acquisition, for instance, in order to establish a foothold in a new, booming industry. But the history of corporate transformation shows you’re more likely to be successful if you seek change in your own backyard.

As White examined the range of product lines and the customer segments served, he noticed a hidden asset that could rescue the company. In the early 1990s, PerkinElmer had branched out in another direction—developing products to amplify DNA—through a strategic alliance with Cetus Corporation. In the process, the company obtained rights to cutting-edge procedures known as polymerase chain reaction technology—a key life-sciences platform. In 1993, the company also acquired a small Silicon Valley life-sciences equipment company, Applied Biosystems (AB)—one more line of instruments to be integrated into PerkinElmer’s.

White began to conceive of a redefined core built around analytical instruments for the fast-growing segment of life-sciences labs. The AB instruments in the company’s catalog, if reorganized and given appropriate resources and direction, could have greater potential than even the original core. White says, “I was struck by how misconceived it was to tear AB apart and distribute its parts across the functions in the organization. I thought, ‘Here is a company whose management does not see what they have.’ So one of the first steps I took was to begin to reassemble the parts of AB. I appointed a new president of the division and announced that I was going to re-form the core of the company over a three-year period around this unique platform with leadership in key life-sciences detection technology.”

Over the next three years, White and his team separated PerkinElmer’s original core business and all the life-sciences products and services into two organizations. The employees in the analytical instruments division were given incentives to meet an aggressive cost reduction and cash flow target and told that the division would be spun off as a separate business or sold to a strong partner. Meanwhile, White set up a new data and diagnostics subsidiary, Celera Genomics, which, fueled by the passion of the scientist Craig Venter, famously went on to sequence the complete human genome. Celera and AB were combined into a new core business organization, a holding company christened Applera.

While Celera garnered the headlines, AB became the gold standard in the sequencing instrument business, with the leading market share. Today it has revenues of $1.9 billion and a healthy net income of $275 million. Meanwhile, the original instrument company was sold to the Massachusetts-based EG&G. (Soon after, EG&G changed its corporate name to PerkinElmer—and has since prospered from a combination that redefined its own core.)

The PerkinElmer-to-Applera transformation offers several lessons. The first is that a hidden asset may be a collection of products and customer relationships in different areas of a company that can be collected to form a new core. The second lesson is the power of market leadership: Finding a subcore of leadership buried in the company and building on it in a focused way created something that started smaller than the original combination but became much bigger and stronger. The third lesson lies in the concept of shrinking to grow. Though it sounds paradoxical and is organizationally difficult for companies to come to grips with, this is one of the most underused and underappreciated growth strategies. (See the sidebar “Shrinking to Grow.”)

Creating a new core based on a previously overlooked business platform is more common than one might think. General Electric, for instance, like IBM, identified an internal business unit—GE Capital—that was undervalued and underutilized. Fueled by new attention and investment, the once sleepy division made more than 170 acquisitions over a ten-year period, propelling GE’s growth. By 2005 GE Capital accounted for 35% of the parent corporation’s profits. Nestlé discovered that it had a number of food and drink products designed to be consumed outside the home. Like the original PerkinElmer, it assembled these products into a new unit, Nestlé Food Services; developed a unified strategy; and effectively created the core of a new multibillion-dollar business.

Untapped Insights into Customers

Most large companies gather considerable amounts of data about the people and businesses that buy their wares. But it’s not always clear how much they actually know about those customers. In a recent series of business seminars I held for management teams, the participants took an online survey. Though nearly all came from well-regarded companies, fewer than 25% agreed with the simple statement “We understand our customers.” In a 2004 Bain survey, we asked respondents to identify the most important capabilities their companies could acquire to trigger a new wave of growth. “Capabilities to understand our core customers more deeply” topped the list.

For just this reason, insights into and relationships with customers are often hidden assets. A company may discover that one neglected customer segment holds the key to unprecedented growth. It may find that it is in a position of influence over its customers, perhaps because of the trust and reputation it enjoys, and that it has not fully developed this position. Or it may find that it has proprietary data that can be used to alter, deepen, or broaden its customer relationships. All these can stimulate growth around a new core.

Harman International, a maker of high-end audio equipment, redefined its core around an unexploited customer segment. In the early 1990s it was focused primarily on the consumer and professional audio markets, with less than 10% of revenues coming from the original-equipment automotive market. But its growth had stagnated and its profits were near zero. In 1993 Sidney Harman, a cofounder, who had left the company to serve as U.S. deputy secretary of commerce, returned as CEO in an attempt to rejuvenate the company.

Harman cast a curious eye on the automotive segment. He realized that people were spending more time in their cars, and that many drivers were music lovers accustomed to high-end equipment at home. Hoping to beef up the company’s sales in this sector, he acquired the German company Becker, which supplied radios to Mercedes-Benz. One day when Harman was visiting their plant, some Becker engineers demonstrated how new digital hardware allowed the company to create high-performance audio equipment in a much smaller space than before. That, Harman says, was the turning point. He invested heavily in digital to create branded high-end automotive “infotainment” systems. The systems proved to have immense appeal both for car buyers and for car manufacturers, who enjoyed healthy margins on the equipment. Based largely on its success in the automotive market, Harman’s market value increased 40-fold from 1993 to 2005.

It is somewhat unusual, of course, to find an untapped customer segment that is poised for such rapid growth. But it isn’t at all unusual for a company to discover that its relationships with customers are deeper than it realized, or that it has more knowledge about customers than it has put to work. Hyperion Solutions, a producer of financial software, was able to reinvent itself around new products and a new sales-and-service platform precisely because corporate finance departments had come to depend on its software for financial consolidation and SEC reporting. “We totally underestimated how much they relied upon us for this very technical and sensitive part of their job,” says Jeff Rodek, formerly Hyperion’s CEO and now the executive chairman. American Express transformed its credit-card business on the basis of previously unutilized knowledge of how different customer segments used the cards and what other products might appeal to them. Even De Beers, long known for its monopolistic practices in the diamond industry, recently redefined its core around consumer and customer relationships. De Beers, of course, had long-standing relationships with everyone in the industry. When its competitive landscape changed with the emergence of new rivals, De Beers leaders Nicky Oppenheimer and Gary Ralfe decided to make the company’s strong brand and its unique image and relationships the basis of a major strategic redefinition. The company liquidated 80% of its inventory—the stockpile that had allowed it for so long to stabilize diamond prices—and created a new business model. It built up its brand through advertising. It developed new product ideas for its distributors and jewelers, and sponsored ad campaigns to market them to consumers. As a result, the estimated value of De Beers’s diamond business increased nearly tenfold. The company is still in the business of selling rough diamonds, but its core is no longer about controlling supply—it’s about serving consumers and customers.

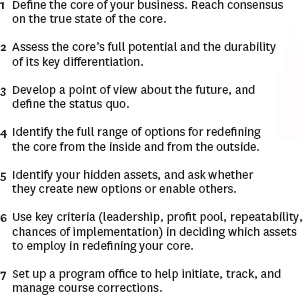

Seven steps to a new core business

Underexploited Capabilities

Hidden business platforms and hidden customer insights are assets that companies already possess; in theory, all that remains is for management to uncover them and put them to work. Capabilities—the ability to perform specific tasks over and over again—are different. Any capability is potentially available to any company. What matters is how individual companies combine multiple capabilities into “activity systems,” as Michael Porter calls them, meaning combinations of business processes that create hard-to-replicate competitive advantage. IKEA’s successful business formula, Porter argued in his 1996 HBR article “What Is Strategy?,” can be traced to a strong and unique set of linked capabilities, including global sourcing, design for assembly, logistics, and cost management.

An underexploited capability, therefore, can be an engine of growth if and only if it can combine with a company’s other capabilities to produce something distinctly new and better. Consider the Danish company Novozymes, now a world leader in the development and production of high-quality enzymes. When it was spun off from its parent corporation in 2000, Novozymes was still largely dependent on relatively low-tech commodity enzymes such as those used in detergents.

Steen Riisgaard, the company’s chief executive, set out to change that, and the key was Novozymes’s underutilized scientific capability. Riisgaard focused the company’s R&D on the creation of bioengineered specialty enzymes. Its scientists worked closely with customers in order to design the enzymes precisely to their specifications. If a customer wanted to remove grease stains from laundry at unusually low temperatures, for instance, Novozymes would collect possible enzyme-producing microorganisms from all over the world, determine which one produced the enzyme closest to what was needed, remove the relevant gene, and insert the gene into an organism that could safely be produced at high volume. Riisgaard likens the process to finding a needle in a haystack, except that Novozymes uses state-of-the-art technology to single out the haystacks and accelerate the search. Such capabilities have shortened product development from five years to two and have set Novozymes apart from its competitors.

Of course, a company may find that it needs to acquire new capabilities to complement those it already has before it can create a potent activity system. Apple indisputably capitalized on its strengths in design, brand management, user interface, and elegant, easy-to-use software in creating the iPod. But it also needed expertise in the music business and in digital rights management. Once it had those, Apple gained access to content by signing up the top four recording companies before competitors could and developing the iTunes Music Store. It also created a brilliantly functional approach to digital rights management with its Fairplay software, which ensures that the music companies obtain a highly controllable revenue stream. This combination of existing and new capabilities proved transformational for Apple.

The highest form of capability development is to create a unique set of capabilities—no longer hidden—that can build one growth platform after another, repeatedly giving a company competitive advantage in multiple markets. Though difficult, this is a strong temptation; indeed, it has proved to be a siren song for many. But a few companies, such as Emerson Electric, Valspar, Medtronic, and Johnson & Johnson, have managed to avoid the rocks. A lesser-known example is Danaher, which only 20 years ago was a midsize company with $617 million in revenues and almost all its business concentrated in industrial tool markets. Danaher developed a set of procedures whereby it can identify acquisitions and then add value to the acquired companies through the so-called Danaher Business System. The system has several phases and dimensions, including cultural values, productivity improvement, sourcing techniques, and a distinctive approach to measurement and control. It has allowed Danaher to expand into six strategic platforms and 102 subunits spanning a wide range of industrial applications, from electronic testing to environmental services. The company’s stock price has risen by more than 5,000% since 1987, outpacing the broader market by a factor of more than five.

It’s somewhat maddening how the assets explored here—PerkinElmer’s undervalued business platform, Harman’s untapped customer insights, Novozymes’s underexploited capabilities—can be so obvious in hindsight and yet were so hard to appreciate at the time. Will you be any better able to see what is under your nose? One thing seems clear: Your next core business will not announce itself with fanfare. More likely, you will arrive at it by a painstaking audit of the areas outlined in this article.

The first step is simply to shine a light on the dark corners of your business and identify assets that are candidates for a new core. Once identified, these assets must be assessed. Do they offer the potential of clear, measurable differentiation from your competition? Can they provide tangible added value for your customers? Is there a robust profit pool that they can help you target? Can you acquire the additional capabilities you may need to implement the redefinition? Like the four essentials of a good golf swing, each of these requirements sounds easily met; the difficulty comes in meeting all four at once. Apple’s iPod-based redefinition succeeded precisely because the company could answer every question in the affirmative. A negative answer to any one of them would have torpedoed the entire effort.

A Growing Imperative for Management

Learning to perform such assessments and to take gradual, confident steps toward a new core business is increasingly central to the conduct of corporate management. Look, for example, at the fate of the Fortune 500 companies in 1994. A research team at Bain found that a decade later 153 of those companies had either gone bankrupt or been acquired, and another 130 had engineered a fundamental shift in their core business strategy. In other words, nearly six out of ten faced serious threats to their survival or independence during the decade, and only about half of this group were able to meet the threat successfully by redefining their core business.

Why do so many companies face the need to transform themselves? Think of the cycle that long-lived companies commonly go through: They prosper first by focusing relentlessly on what they do well, next by expanding on that core to grow, and then, when the core has lost its relevance, by redefining themselves and focusing anew on a different core strength. It seems clear that this focus-expand-redefine cycle has accelerated over the decades. Companies move from one phase to another faster than they once did. The forces behind the acceleration are for the most part well known. New technologies lower costs and shorten product life cycles. New competitors—currently in China and India—shake up whole industries. Capital, innovation, and management talent flow more freely and more quickly around the globe. The churn caused by all this is wide-ranging. The average holding period for a share of common stock has declined from three years in the 1980s to nine months today. The average life span of companies has dropped from 14 years to just over ten, and the average tenure of CEOs has declined from eight years a decade ago to less than five today.

Business leaders are acutely aware of these waves of change and their ramifications. In 2004 my colleagues and I surveyed 259 senior executives around the world about the challenges they faced. More than 80% of them indicated that the productive lives of their strategies were getting shorter. Seventy-two percent believed that their leading competitor would be a different company in five years. Sixty-five percent believed that they would need to restructure the business model that served their primary customers. As the focus-expand-redefine cycle continues to pick up speed, each year will find more companies in that fateful third phase, where redefinition is essential. For most, the right way forward will lie in assets that are hidden from view—in neglected businesses, unused customer insights, and latent capabilities that, once harnessed, can propel new growth.

CHRIS ZOOK leads the Global Strategy Practice at Bain & Company and is the author of Unstoppable (Harvard Business Review Press, 2007), from which this article is adapted.

Originally published in April 2007. Reprint R0704D