Chapter 12. Procurement management: Getting some help

Some jobs are just too big for your company to do on its own. Even when the job isn’t too big, it may just be that you don’t have the expertise or equipment to do it. When that happens, you need to use Procurement Management to find another company to do the work for you. If you find the right seller, choose the right kind of relationship, and make sure that the goals of the contract are met, you’ll get the job done, and your project will be a success.

Victim of her own success

Kate’s last project went really well. In fact, maybe a little too well. The company’s customer base grew so much that now the IT department’s technical support staff is overwhelmed. Customers who call up looking for technical support have to spend a long time on hold, and that’s not good for the company.

Calling in the cavalry

Kate: No problem. The hard part will be figuring out how to manage the transition. Are we going to try to expand the team immediately, or call in a supplier to help us out?

Ben: Whoa, hold on there! Is going outside the company even an option?

Kate: Look, our tech support team is already at full capacity, and it’ll take months to upgrade the facilities to handle more people... not to mention hire and train up the staff. We may be able to handle it ourselves, but there’s a good chance that the easiest way to get the job done is to go outside our company to find a vendor to do the work.

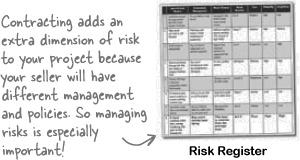

Ben: But isn’t it kind of risky thinking about working with another company? I mean, what if they go out of business during our project? Or what if they cost too much?

Kate: Well, we’ll need to make sure that we answer those questions. But this isn’t the first time our company’s brought on a contractor like this. The legal department has done this kind of thing before. I’ll set up a meeting with somebody over there and see if they can help us out.

Ben: Okay, you can follow up on that. But I’m still not sure about this.

Sometimes you need to hire an outside company to do some of your project work. That’s called procurement, and the outside company is called the seller.

You need to be involved because it’s your project, and you’re responsible for it.

One of the most common mistakes people make on the exam (and in real life) is to assume that if another company is selling products or services for your project and they don’t deliver, it’s not your problem. After all, you’ve got a contract with the company, right? So if they don’t deliver, they won’t get paid.

Well, it’s not that simple. Yes, there are plenty of sellers who fail to deliver on their contracts. But for each seller that doesn’t deliver, there’s a frustrated project manager whose project ran into trouble because of it. That’s why a lot of the Procurement Management tools and techniques are focused on selecting the right seller and communicating exactly what you’ll need to the people doing the work.

Watch it!

The PMP® exam is based on contracting laws and customs in the United States.

Are you used to working in a country that ISN’T the U.S.? Then you should be especially careful about these processes. You may be used to working with contracts in a way that isn’t exactly the same as how they’ll work on the exam questions. Luckily, the U.S. government publishes a lot of information on contracting at http://www.acquisition.gov/. Take a look at the site if you want a little more background.

Ask the legal expert

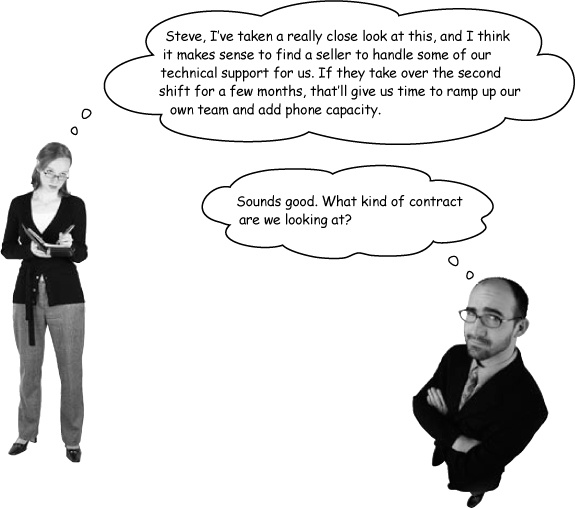

Kate: Thanks for coming by, Steve. We’re looking for a contractor to handle tech support while we bring on more people in our call center. How do we normally handle this stuff?

Steve: Here’s how it usually works. I’ll actually write the contract and do the negotiation. But before I do that, I’ll need to sit down with you to understand what the contract has to accomplish.

Kate: So I’m not involved at all?

Steve: Oh, you’re definitely involved. You need to help with the negotiations, because you’re the only person who really understands what we’re trying to accomplish with the contract.

Kate: Okay, that makes sense. So when do we get started?

Steve: Well, not so fast. We need to be really sure that the way we pick our vendors is absolutely fair. We’ve got some company guidelines that you’ll need to follow. And once we’ve got the contract signed and the work is underway, we’ll need to meet to make sure the contract is really being followed. And if there’s a problem and we need to negotiate a change to the contract, you’ll need me to do it.

Kate: Okay, I can handle that. So should I start working on something to send out to sellers?

Steve: Not quite. Before we even get started with all of that, are you sure we really need to contract this work?

Anatomy of a contract

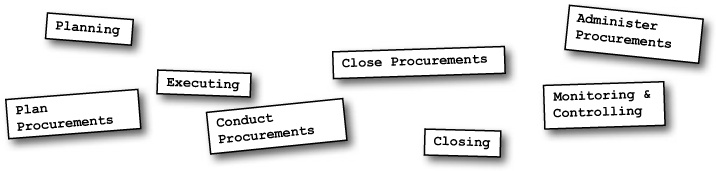

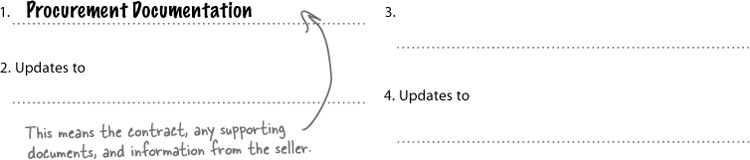

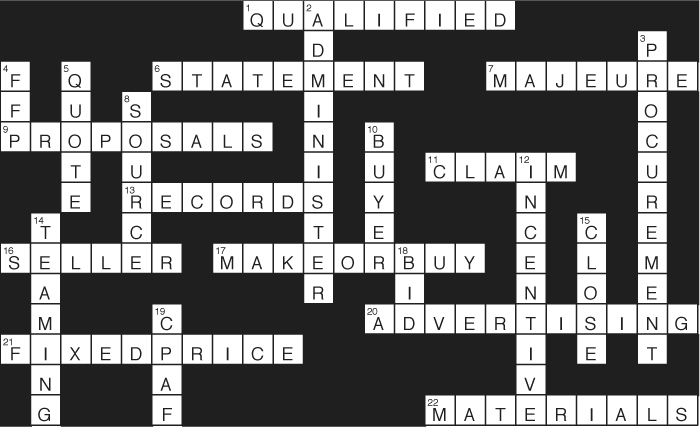

Procurement is pretty intuitive, and the four Procurement Management processes follow a really sensible order. First you plan what you need to contract; then you plan how you’ll do it. Next, you send out your contract requirements to sellers. They bid for the chance to work with you. You pick the best one, and then you sign the contract with them. Once the work begins, you monitor it to make sure the contract is being followed. When the work is done, you close out the contract and fill out all the paperwork.

Plan Procurements Here’s where you take a close look at your needs, to be sure that you really need to create a contract. You figure out what kinds of contracts make sense for your project, and you try to define all of the parts of your project that will be contracted out. You’ll need to plan out each individual contract for the project work and work out how you’ll manage it. That means figuring out what metrics it will need to meet to be considered successful, how you’ll pick a seller, and how you’ll administer the contract once the work is happening. | Conduct Procurements This process is all about getting the word out to potential contract partners about the project and how they can help you. You hold bidder conferences and find qualified sellers that can do the work. Next, you evaluate all of the responses to your procurement documents and find the seller that suits your needs the best. When you find them, you sign the contract, and then the work can begin. |

You can have several contracts for a single project

The first Procurement Management process is Plan Procurements. It’s a familiar planning process, and you use it to plan out all of your procurement activities for the project. The other three processes are done for every contract. Here’s an example. Say you’re managing a construction project, and you’ve got one contract with an electrician and another one with a plumber. That means you’ll go through those three processes two separate times, once for each contractor.

Administer Procurements When the contract is underway, you stay on top of the work and make sure the contract is adhered to. You monitor what the contractor is producing and make sure everything is running smoothly. Occasionally, you’ll need to make changes to the contract. Here’s where you’ll find and request those changes. | Close Procurements When the work is done, you’ll close your contract out. You’ll make sure that the product that is produced meets the criteria for the contract, and that the contractor gets paid. |

Start with a plan for the whole project

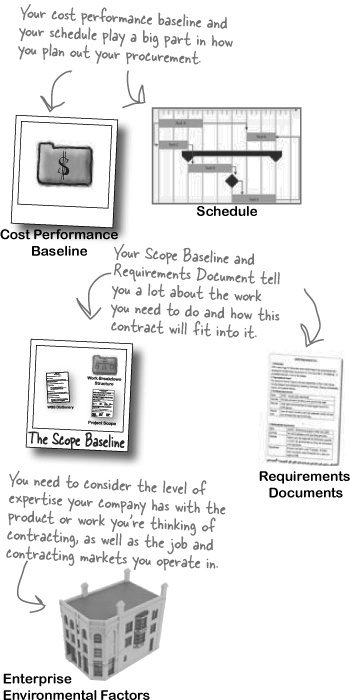

You need to think about all of the work that you will contract out for your project before you do anything else. The Plan Procurements process is all about figuring that out, and writing up a plan for how you’ll do it.

Note

There are four other inputs: risk-related contracts decisions, activity-related resource requirements, activity cost estimates, and Organizational Process Assets. Take a minute and think about how you’d use them.

Note

the planned delivery dates for the work or products you are contracting

the company’s standard documents you will use

the contract types you plan to use, and any metrics that will be used to measure the contractor’s performance

any constraints or assumptions you need to know about all of the contracts you plan to create for your project

Because sometimes it’s not worth having your team do part of the job.

If your company needed to renovate your office, would you hire the carpenter, electrician, and builders? Would you buy the power tools, cement mixer, trucks, and ladders? Of course not. You’d hire a contractor to do the work, because it would cost too much to buy all that stuff for one job, and you wouldn’t want to hire people just for the job and then fire them when it was done. Well, the same goes for a lot of jobs on your projects. You don’t always want to have your company build everything. There are a lot of jobs where you want to hire a seller.

Note

There are a lot of words for the company you’re hiring: contractor, consultant, external company... but for the PMP exam, you’ll typically see the term “seller.”

Relax

It’s natural to feel a little nervous about this contracting stuff.

A lot of project managers have only ever worked with teams inside their own companies. All this talk of contracts, lawyers, proposals, bids, and conferences can be intimidating if you’ve never seen it before. But don’t worry. Managing a project with a contractor is really similar to managing one that uses your company’s employees. There are just a few new tools and techniques that you need to learn... but they’re not hard, and you’ll definitely get the hang of them really quickly.

The decision is made

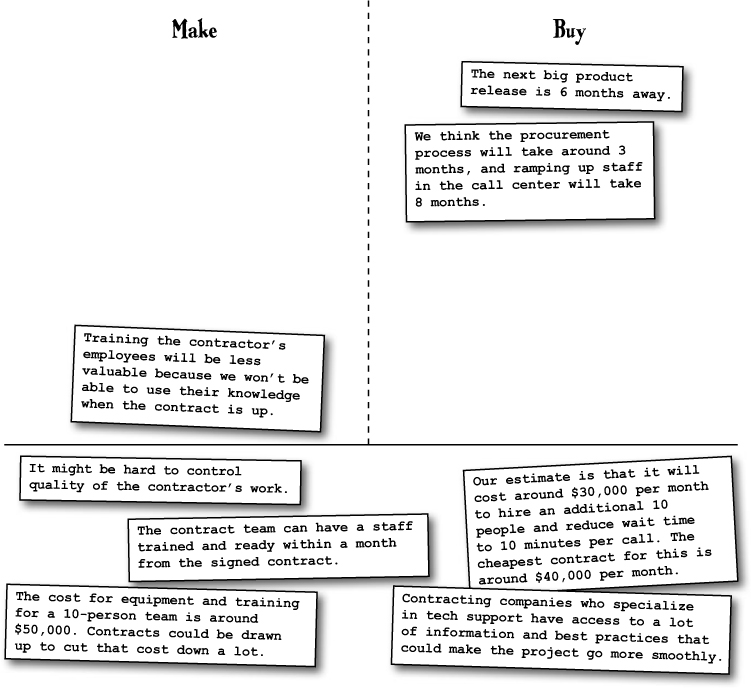

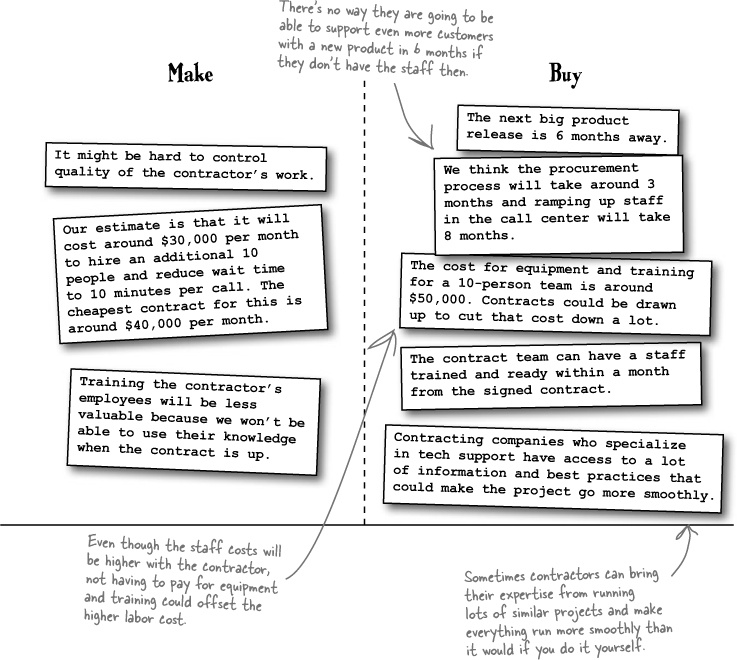

Doing make or buy analysis just means understanding the reasons for the contract and deciding whether or not to contract out the work. Once you’ve done that, if you still think contracting is an option, then you should have a good idea of what you need to get out of the contracting process.

Types of contracts

It’s a good idea to know a little bit about the most commonly used contract types. They can help you come up with a contract that will give both you and the seller the best chance of success.

Note

If you want to see a really thorough overview of the different types of contracts, check out the U.S. Federal Acquisition Regulation web site:

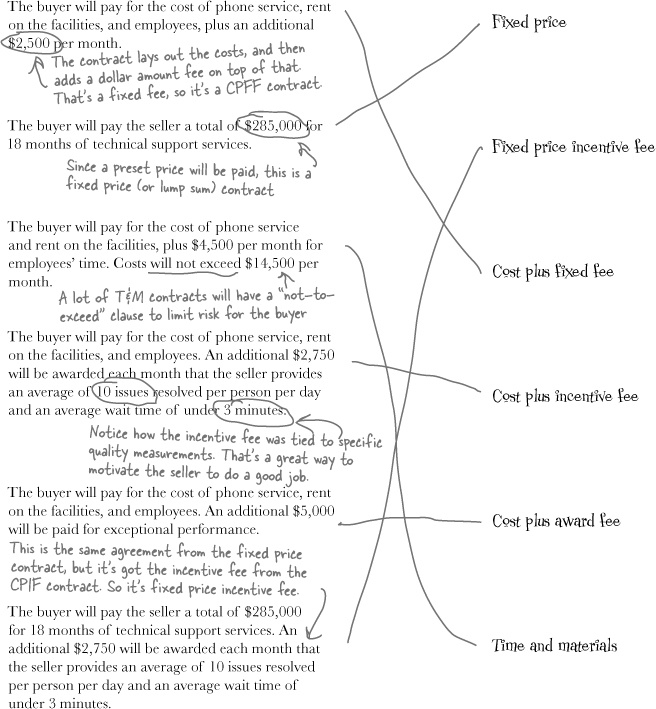

Fixed price contracts

Fixed price (FP) means that you are going to pay one amount regardless of how much it costs the contractor to do the work. A fixed price contract only makes sense in cases where the scope is very well known. If there are any changes to the amount of work to be done, the seller doesn’t get paid any more to do it.

Fixed price plus incentive fee (FPIF) means that you are going to pay a fixed price for the contract and give a bonus based on some performance goal. You might set up a contract where the team gets a $50,000 bonus if they manage to deliver an acceptable product before the contracted date. If the fixed-price contract does not include a fee, it’s often referred to as a firm fixed price (FFP) contract.

Cost-reimbursable contracts

Note

Don’t worry about trying to cram these into your head right now—you’ll get a lot of practice with them throughout the chapter.

Costs plus fixed fee (CPFF) means what it says. You pay the seller back for the costs involved in doing the work, plus you agree to an amount that you will pay on top of that.

Costs plus award fee (CPAF) is similar to the CPFF contract, except that instead of paying a fee on top of the costs, you agree to pay a fee based on the buyer’s evaluation of the seller’s performance.

Costs plus incentive fee (CPIF) means you’ll reimburse costs on the project and pay a fee if some performance goals are met. Kate could set up her project using this contract type by suggesting that the team will get a $50,000 bonus if they keep the average wait time for the calls down to seven minutes per customer for over a month. If she were on a CPIF contract, she would pay the team their costs for doing the work, and also the a $50,000 bonus when they met that goal.

Time and Materials

Time and Materials (T&M) is used in labor contracts. It means that you will pay a rate for each of the people working on your project plus their materials costs. The “Time” part means that the buyer pays a fixed rate for labor—usually a certain number of dollars per hour. And the “Materials” part means that the buyer also pays for materials, equipment, office space, administrative overhead costs, and anything else that has to be paid for. The seller typically purchases those things and bills the buyer for them. This is a really good contract to use if you don’t know exactly how long your contract will last, because it protects both the buyer and seller.

Note

A lot of people say that the T&M contract is a lot like a combination of a cost-plus and fixed price contract, because you pay a fixed price per hour for labor, but on top of that you pay for costs like in a cost-plus contract.

Even if your project has several contracts, they don’t all have to be the same type. That’s why you need to administer each one separately.

More about contracts

There are just a few more things you need to know about any contract to do procurement work.

Every contract needs to outline the work to be done and the payment for that work.

You might see an exam question that mentions “consideration”—that’s just another word for the payment.

Remember in Risk Management how you used insurance to transfer risk to another company? You did that using a special kind of contract called an insurance policy.

You might get a question that asks about force majeure. This is a kind of clause that you’ll see in a contract. It says that if something like a war, riot, or natural disaster happens, you’re excused from the terms of the contract.

Always pay attention to the point of total assumption.

The point of total assumption is the point at which the seller assumes the costs. In a fixed price contract, this is the point where the costs have gotten so large that the seller basically runs out of money from the contract and has to start paying the costs.

You should always make sure both the buyer and seller are satisfied.

When you negotiate a contract, you should make sure that the buyer and the seller both feel comfortable with the terms of the contract. You don’t want the people at the seller’s company to feel like they got a raw deal—after all, you’re depending on them to do good work for your project.

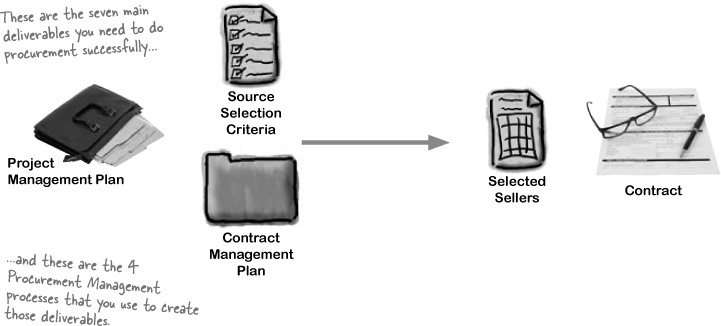

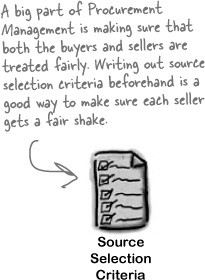

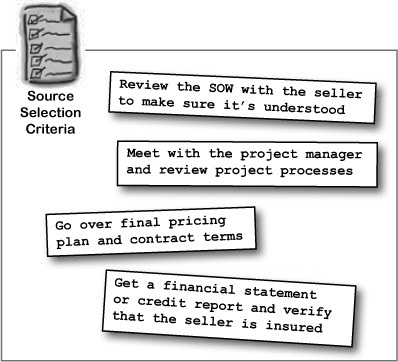

Figure out how you’ll sort out potential sellers

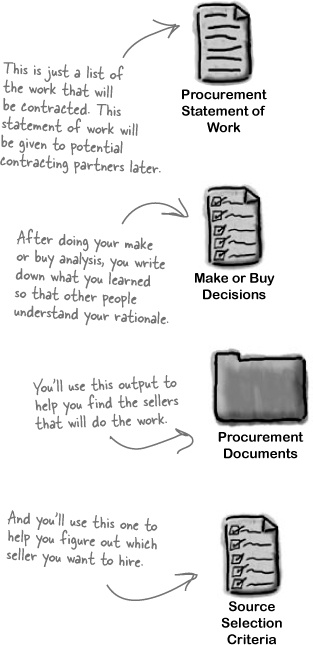

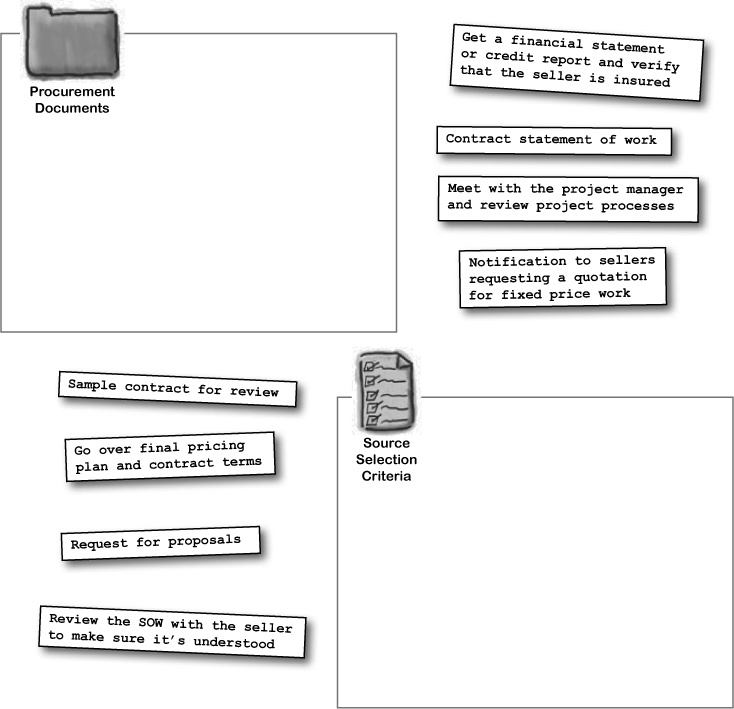

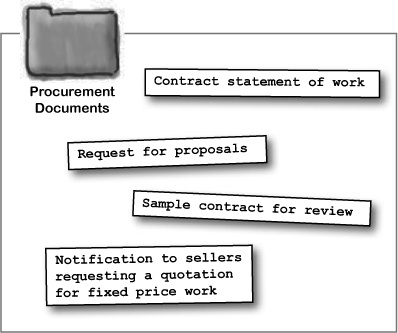

The two big outputs of Plan Procurement are the procurement documents and source selection criteria. The procurement documents are what you’ll use to find potential sellers who want your business. The source selectrion criteria are what you’ll use to figure out which sellers you want to use.

There are a bunch of different documents you might want to send to sellers who want to bid on your work.

You’ll usually include the contract statement of work (SOW) so that sellers know exactly what work is involved.

An invitation for bid (IFB) is a document that tells sellers that you want them to submit proposals. You’ll also hear of people using requests for information (RFI) and requests for proposals (RFP).

There’s another kind of invitation—an invitation for quote (IFQ). This is a way to tell sellers that you want them to give you a quote on a fixed-price contract to do the work.

A purchase order is something you’ll send out to a seller who you know that you want to work with. It’s an agreement to pay for certain goods or services.

In some cases you’ll want to allow for more flexibility in your contract. If you’re hiring a seller to build something for you that you’ve never built before, you’ll often encourage them to help you set the scope instead of locking it down.

Decide in advance on how you want to select the sellers.

There are a lot of ways you can select a potential seller. Figuring out if a seller is appropriate for your work is something that takes a lot of talking and thinking—and there’s no single, one-size-fits-all way of selecting sellers. But there are some things that you should definitely look for in any seller:

Note

You’d be amazed at how many sellers respond to bids that they have no business responding to. You definitely need to make sure the seller has the skill and capacity to do the work you need.

Can the seller actually do the work you need done?

How much will the seller charge?

Can the seller cover any costs and expenses necessary to do the job?

Are there subcontractors involved that you need to know about?

Does the seller really understand everything in the SOW and contract?

Is the seller’s project management capability up to the task?

You always put together procurement documents and source selection criteria before you start talking to individual sellers who want your business.

Get in touch with potential sellers

The next step in procurement is pretty straightforward. You use the Conduct Procurements process to, well, get the word out to sellers and see what kind of responses you get. Once you narrow down your list of sellers to a few who look like they might be good candidates, you evaluate all of their responses against your source selection critieria and choose the vendor you’re going to work with. All that’s left to do after that is to get it all on paper... and then you award the contract!

Use outputs from the Plan Procurements process to find the right seller

When you perform the Conduct Procurements process, you’ll start with some of the outputs you created in Plan Procurements. Here’s how you’ll use them:

The Make or Buy decisions you made will come in handy because they’ll tell you what you need to find a contractor to help out with and what you’ll do yourself. | Use the Source Selection Criteria to evaluate the sellers that respond to you. By evaluating all of your sellers using the same criteria, you’ll be sure that you evaluate everyone fairly and find the right seller for your company. | ||

Procurement documents will have all of the information that you’ll actually give to potential sellers to help them bid on your contract. Two of the most commonly used procurement documents are the RFI and the RFP. RFI - Request for information documents are sent to potential sellers to ask for information about their capability to do the work. RFP - Request for Proposal is when you give a seller the opportunity to examine your procurement documents and write up a proposal of how they’d do the work. | The procurement statement of work is where you write out all of the work that needs to be done by a contractor. It tells you the scope of the work that you’re going to contract to another company. |

Pick a partner

You’ve figured out what services you want to procure, and you’ve gone out and found a list of potential sellers. Now it’s time to choose one of them to do the project work—and that’s exactly what you do in Conduct Procurements.

Two months later...

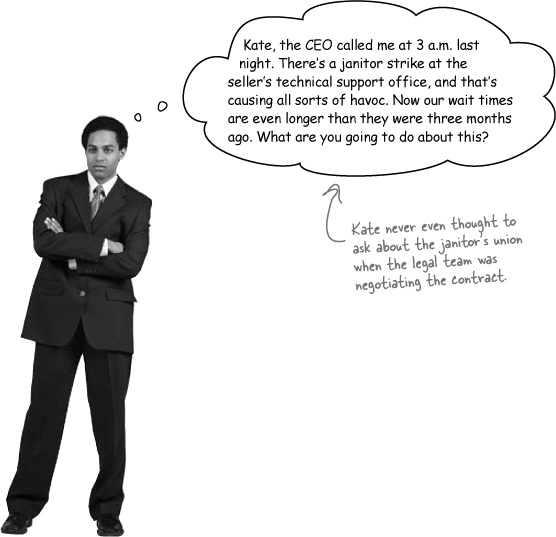

Kate’s procurement project had been going really well... or so she thought. But it turns out there’s a problem.

Watch it!

Keep an eye out for questions that ask about unions, even when they don’t have to do with contracts or procurement management.

When you work with a union, even if it’s through a seller, then the union contract (also called a collective bargaining agreement) can have an impact on your project. That means you need to consider the union itself a stakeholder, and when you do your planning you need to make sure any union rules and agreements are considered as constraints.

Keep an eye on the contract

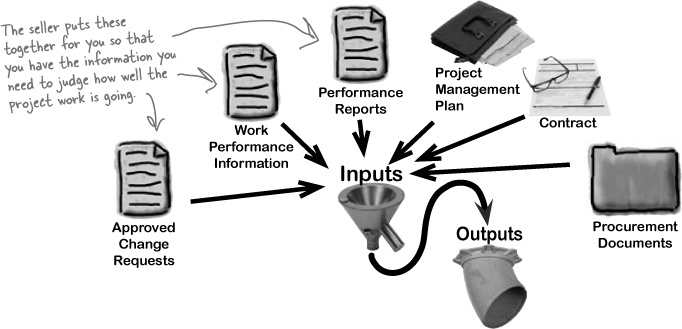

You wouldn’t just start off a project and then assume everything would go perfectly, would you? Well, you can’t do that with a contract either. That’s why you use the Administer Procurements process.

The idea behind the Administer Procurements process is that staying on top of the work that the seller is doing is more difficult than working with your own project. That’s because when you hire a seller to take over part of your project, the team who’s doing the work doesn’t report to you. That’s why the first three inputs are especially important. The approved change requests are the way that you change the terms of the contract if something goes wrong, and the work performance information and performance reports are how the seller tells you how the project is going.

Stay on top of the seller

The tools and techniques for Administer Procurements are all there to help you work with the seller. Some of them help you look for any potential problems with the seller and make changes to correct them. Others help you with the day-to-day administration work that you need to do in order to keep your project running.

Tools and techniques to keep your project running

Payment System Your partner won’t be very happy if you don’t pay. The payment system is how your company pays its sellers. It’s usually established by an Accounting or Accounts Receivable department. | Records Management System There are a lot of records produced by a typical contract: invoices, receipts, communications, memos, emails, instructions, clarifications, etc. You’ll need to put a system in place to manage them. |

Tools and techniques to find and fix problems

Claims Administration When there’s a dispute between a buyer and a seller, that’s called a claim. Most contracts have some language that explains exactly how claims should be resolved—and since it’s in the contract, it’s legally binding, and both the buyer and seller need to follow it. | Performance Reporting The easiest way for you to keep track of the contract work being done is to write up performance reports. These are exactly like the performance reports that you saw earlier in the book—you’ll use them to monitor the project work and report on the progress to your company’s management. | Procurement Performance Review Most contracts lay out certain standards for how well the seller should do the job. Is the seller doing all the work that was agreed to? Is the work being done on time? The buyer has the right to make sure this is happening, and the way to do this is to go over the performance of the seller’s team. |

Inspections and Audits This tool is how the buyer makes sure that the product that the seller produces is up to snuff. This is where you’ll check up on the actual product or service that the project is producing to make sure that it meets your needs and the terms of the contract. | Contract Change Control System This is just like all of the other change control systems that you’ve seen already. It’s a set of procedures that are set up to handle changes in the contract. You might have a different one for every contract in your project. |

Buyer-conducted performance reviews let buyers check all of the work that the sellers are doing.

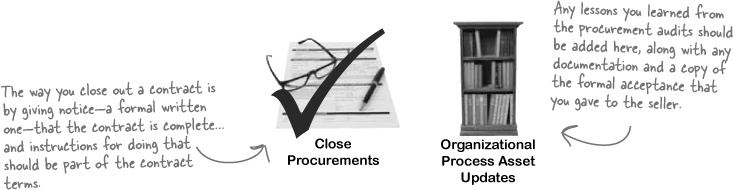

Close the contract when the work is done

When the seller’s work is done, it’s time to close the contract, and that’s when you use the Close Procurements process. Even if your contract ends disastrously (or in court), you still need to close out the contract so that you can make sure all of your company’s responsibilities are taken care of—and that you learn from the experience.

Kate closes the contract

The 18-month contract’s ready to close! The seller did a great job handling technical support, and that gave Kate and Ben the time they needed to ramp up their own company’s team and facilities.

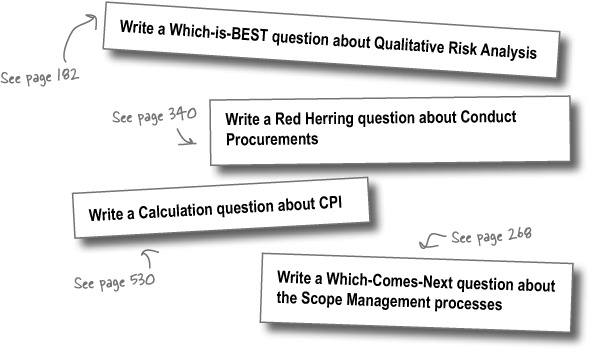

Question Clinic: BYO Questions

Did you come up with a good question? Join the Head First PMP community and upload your question at http://www.headfirstlabs.com/PMP