Chapter 2. Beyond Scaffolding: Rails apps, made to order

So what’s really going on with Rails? You’ve seen how scaffolding generates heaps of code and helps you write web applications wicked fast, but what if you want something a little different? In this chapter you’ll see how to really seize control of your Rails development and take a look underneath the hood of the framework. You’ll learn how Rails decides which code to run, how data is read from the database, and how web pages are generated. By the end, you’ll be able to publish data the way you want.

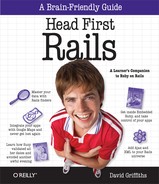

MeBay, Inc. needs your help

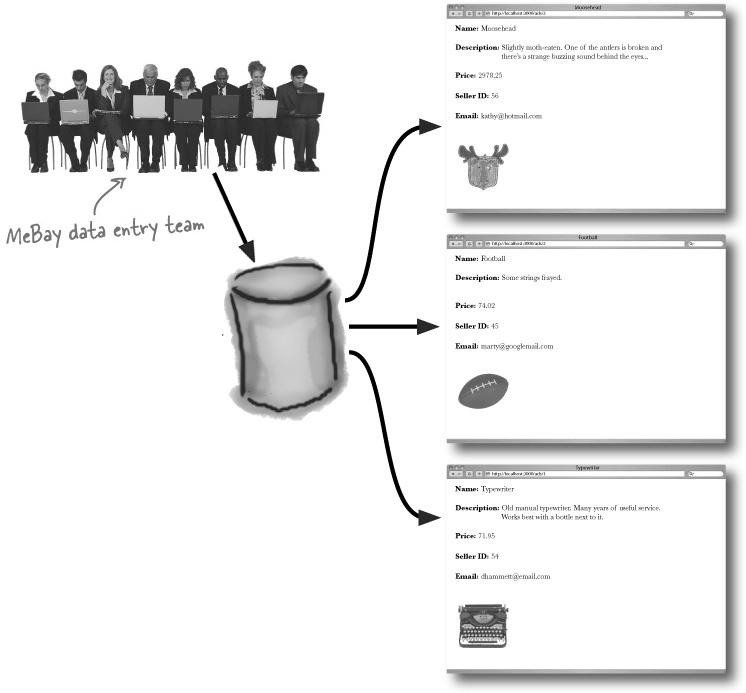

MeBay, Inc. is a sales company that helps people sell their unwanted stuff online. They need a new version of their site, and they need you to help them out.

To place an ad on the site, the seller calls MeBay on their toll-free number, and gives their seller ID and the details of the item they want to sell. MeBay has their own data entry system, and your application is needed to publish the MeBay ads online.

Scaffolding does WAY too much

MeBay want an application that does less than a scaffolded app would. Scaffolding’s great, but some applications are so simple that you’ll sometimes be better off building your app manually.

So why’s that? Well, if you write the code yourself, the application will be simpler and easier to maintain. The downside to this is that in order to build a Rails web app manually, you need to go under the hood and understand how Rails really works.

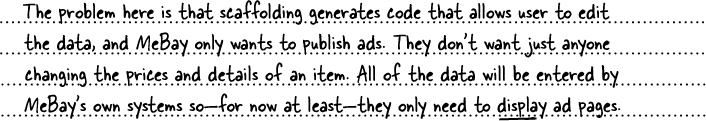

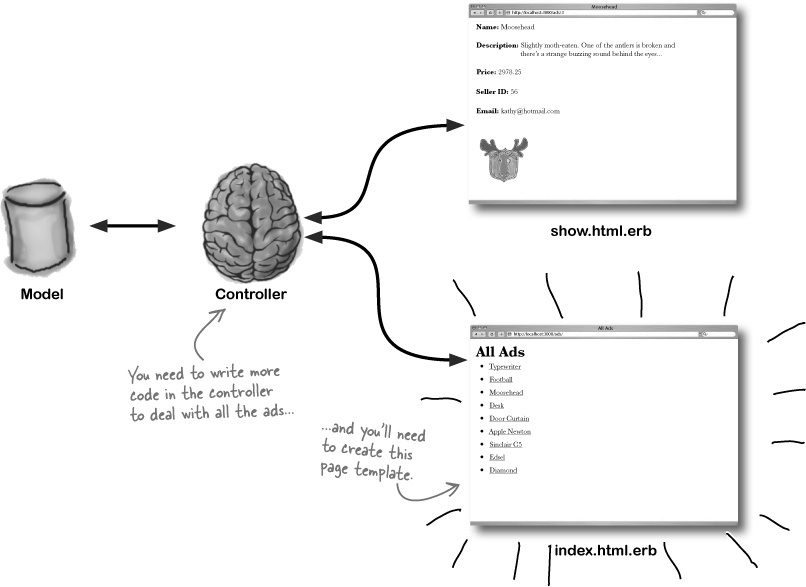

Let’s start by looking at what code you need to create for MeBay:

To build an app without scaffolding, you need to understand how Rails really works.

So which code will you write first?

Let’s start by generating the MeBay model...

It’s a good idea to begin with creating the model code, because the structure of the data in the model affects both the controller and the view.

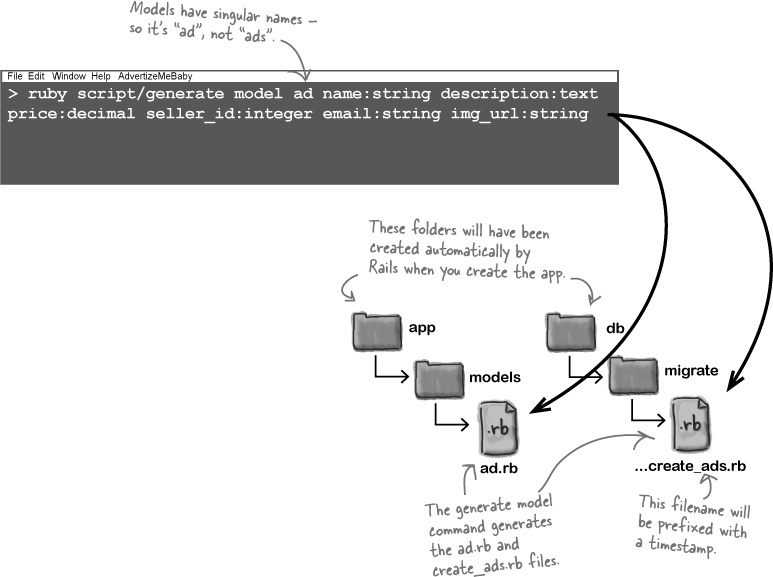

Creating model code is very similar to creating scaffolding. In fact, the only difference is that you replace the word “scaffold” with the word “model,” like this:

The model-generator command creates two key scripts within the app and db subfolders:

the model class

(app/models/ad.rb)andthe data migration

(db/migrate/..._create_ads.rb).

The migration is a Ruby script that can connect to the database and create a table for the ads. To run this script and create the table, we need to use rake.

Note

This is just like we did in Chapter 1. rake figures out which migrations to run based on timestamps.

...and then we’ll actually create the table using rake

To create the table, we need to call the migration using the rake db:migrate command:

Remember, the rake db:migrate command creates a table in the database using the ..._create_ads.rb script you just created with model.

But if you were to look really closely at the table it creates, you’d see a strange thing. Rails creates three extra columns in the table without being asked.

These are “magic columns”: id, created_at, and updated_at. The id column is a generated primary key, and created_at and updated_at record when the data is entered or updated.

Do this!

Rake creates a table for you in the database, but what it doesn’t do is populate that table with data for you to experiment.

You’re going to need some data in the table before we get much further. Fortunately, the kind folks at MeBay Inc. have left a copy of their test data for you at the Head First website. Point your browser to

www.headfirstlabs.com/books/hfrails for a full set of instructions and the data.

Make sure you do this, or you’ll hit problems later on.

But what about the controller?

The model isn’t a lot of use on its own. You need some code that uses the data the model produces, and that’s the job of the controller.

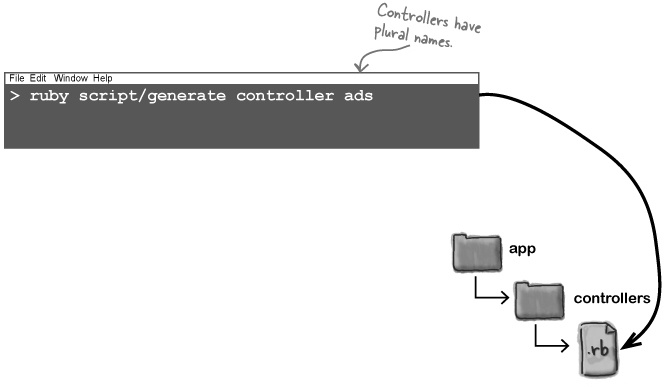

Just like scaffolding and the model, controllers have their own generators. Use the generate controller command below to generate an empty controller class:

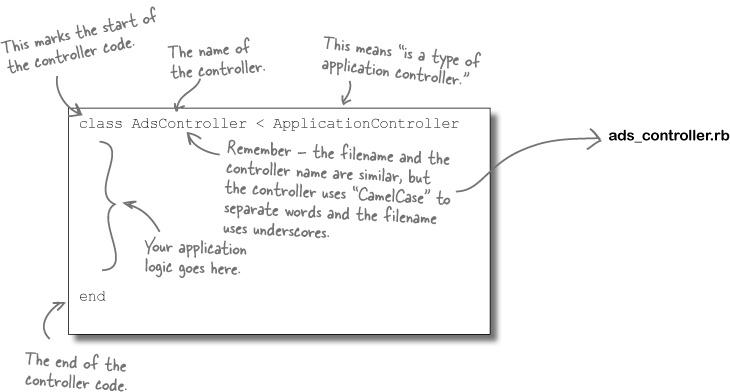

This command generates a class file for your controller at app/controllers/ads_controller.rb. If you open the file with a text editor, you’ll find some Ruby code like this:

We’ll come back to what code needs to be added to this class in just a few pages... for now, it’s just cool that we didn’t have to write any of this Ruby- and Rails-specific syntax.

Geek Bits

CamelCase means using uppercase within identifiers that consist of more than one word to help you make out the individual words.

We’ve created the model and controller, now let’s move onto the view...

The view is created with a page template

So what view code do we need to create? The MeBay web app only needs a single page, and this page will be used as a template for all of the ads on the website. For this reason, pages in Rails are often called page templates (or simply templates).

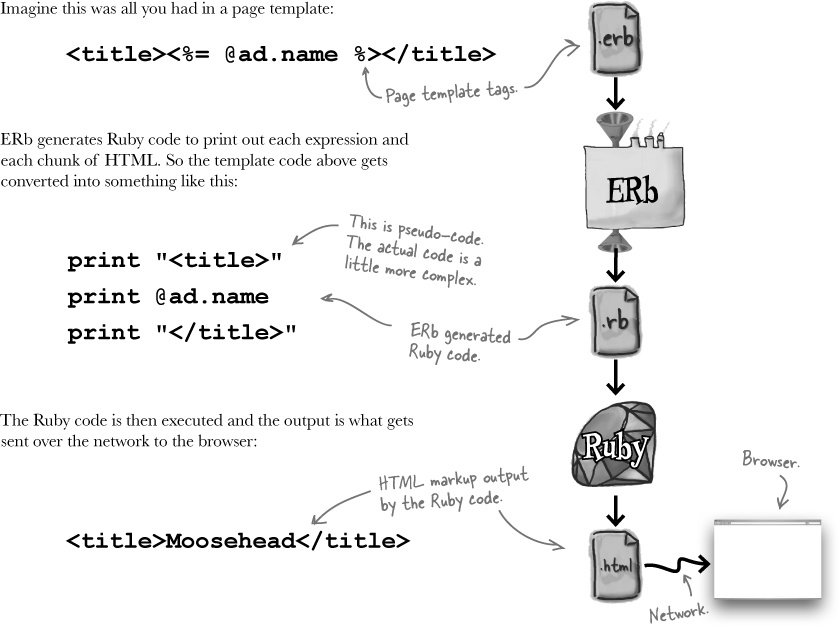

Web pages are created from templates by Embedded Ruby (called ERb), and this is part of the standard Ruby library. If someone asks for for ad #3, ERb will generate the HTML web page for the ad using the page template and data from the model.

So how does ERb produce web pages?

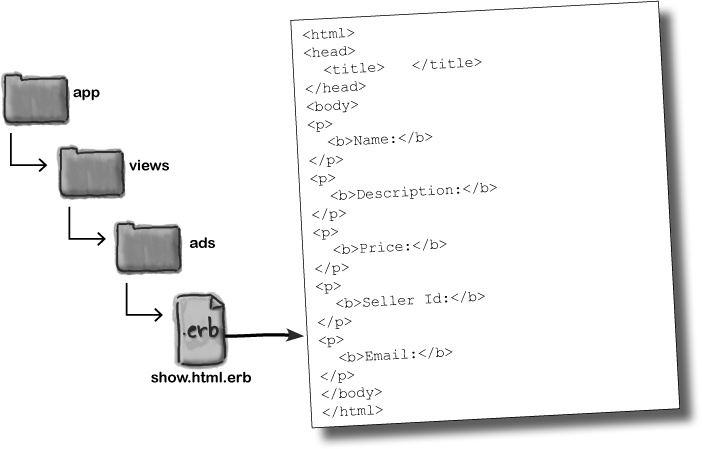

The page template contains HTML

When you generated the model and the controller, Rails generated Ruby code. The view’s a little different though. The application has an HTML interface, so it makes sense that the view code is written in HTML, too.

To create the ad template, open up a text editor and create a file called show.html.erb and save it in app/views/ads. Here’s what you need the contents of show.html.erb to look like:

At the moment the template looks pretty blank, but you’ll see in a little while how the controller can cleverly insert values into it.

So what does the actual web app look like?

Embedded Ruby (ERb) creates web pages from a template.

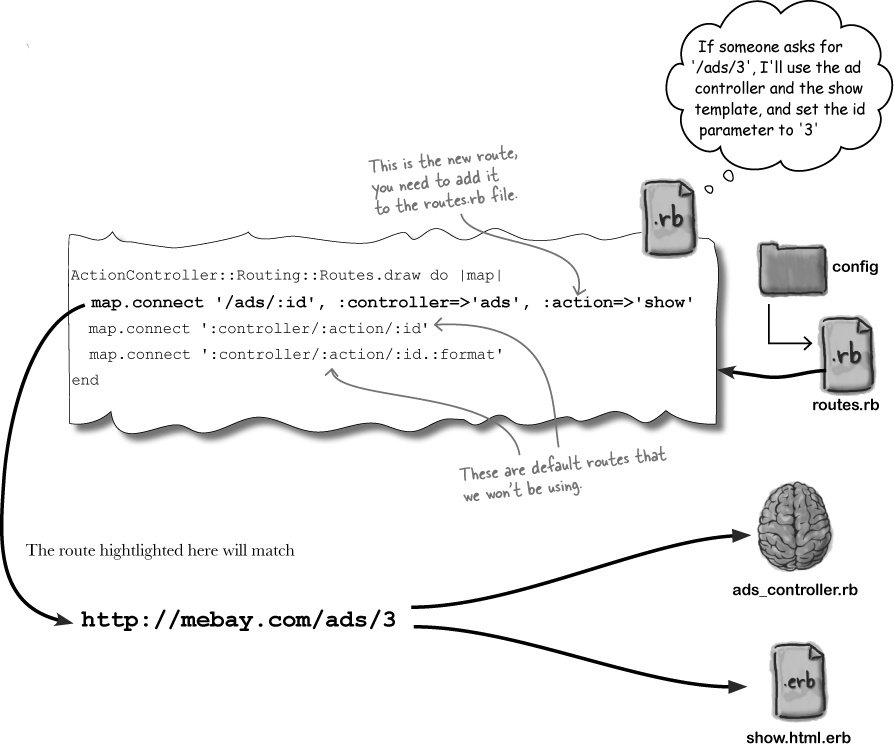

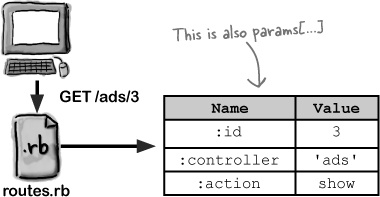

A route tells Rails where your web page is

Rails needs a rule to say which code to run for a given URL. It’s one of the very few times where Rails actually needs some configuration.

The rules that Rails uses to map URL paths to code are called routes. Routes are defined in a Ruby program in config/routes.rb, and we need to add a new route for the show.html.erb template:

—to use ads_controller.rb as the controller code, and show.html.erb as the page template.

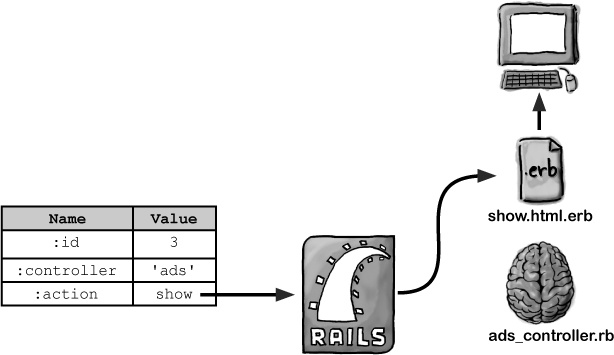

But how did this actually work? What happened?

Behind the scenes with routes

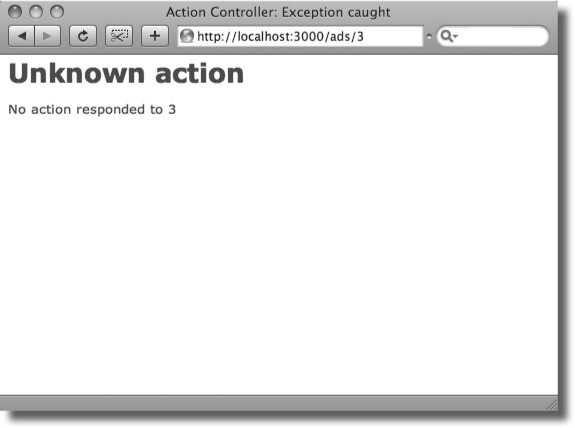

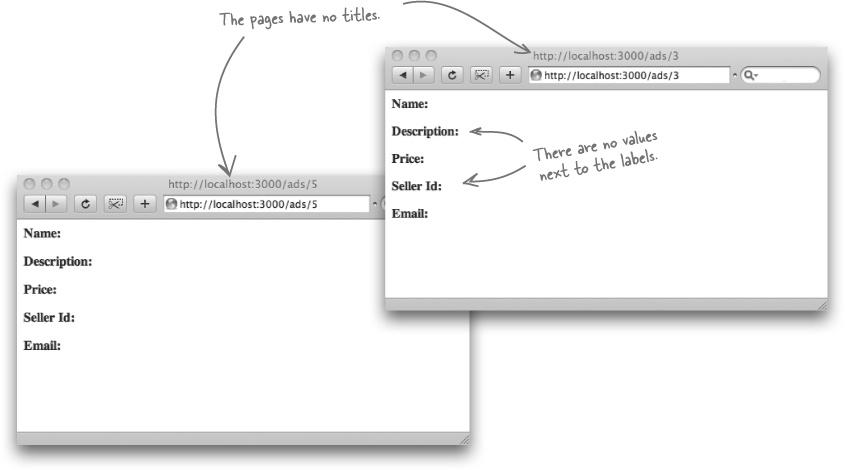

The view doesn’t have the data to display app

Look back at show.html.erb. This file is used to create the pages for each of the ads— and that’s exactly what the template has done:

Although we put the main skeletal parts of the HTML in place— the labels, the body and head sections—there were a couple of things that were missed out. We haven’t specified:

What data needs to be displayed

or

Where in the page that data needs to be inserted.

So what should the page show?

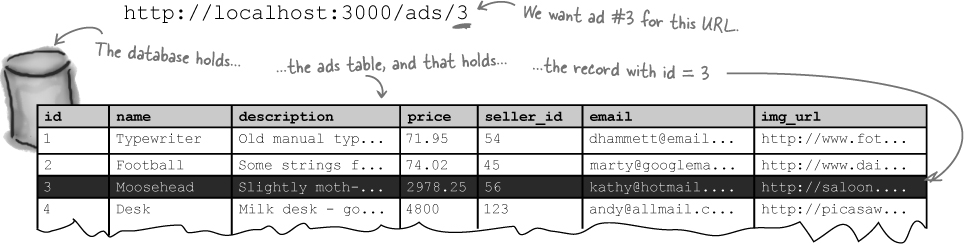

We need the ad page to display the data for the ad number specified in the URL. As an example, here’s the URL for ad #3:

The first thing you need to do is to tell the model to read the record from the ads table in the database with an id number that’s the same as the id number in the URL. If the user asks for the page for ad #3, the model needs to be told to read the record with id = 3.

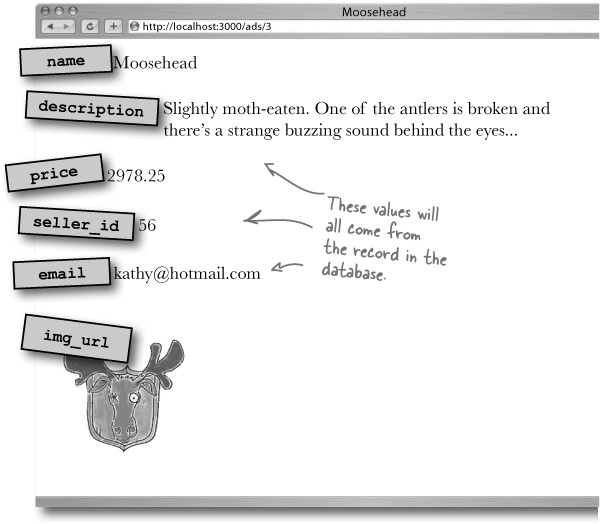

We need to display the data in the right place

Reading the data’s just half the story. Once the model’s read the data, it needs to send the data to the view. The view then needs to know where to display the data in each of the pages. Each of the fields in the record needs to be displayed next to the corresponding labels in the web pages. Plus you need to use the value in the img_url column to insert an image of the sales item into the page.

So which part of the system is responsible for asking for the appropriate data from the database and then sending the data to the view?

The controller sends the ad to the view

Let’s see what the code in the controller will look like and how it will work:

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

The completed code in ads_controller.rb needs to go inside a method called show—which matches the name of the :action parameter created by routes.rb

But how exactly does the model read the data from the database, and how will the page template use that data?

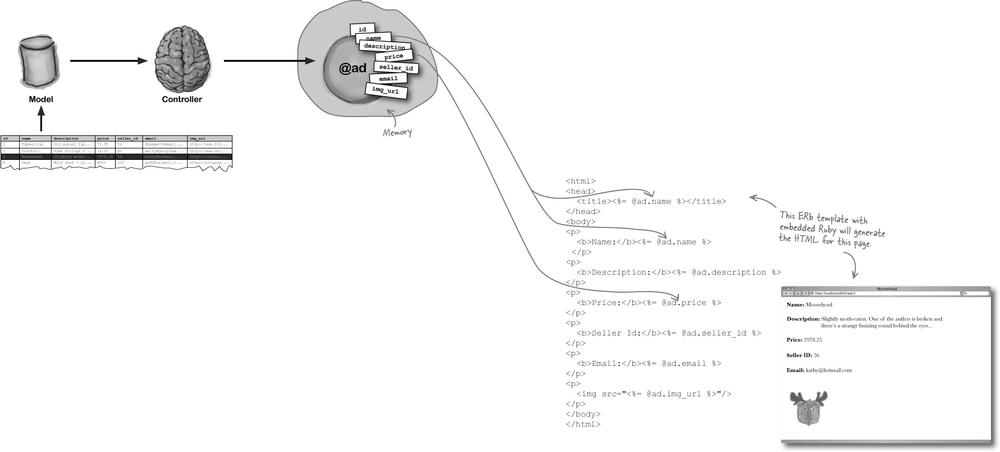

Rails turned the record into an object

When Rails reads the record from the database that matches the id in the URL, the data from the record is converted into an object. That object’s stored in memory and the controller assigns it the name @ad.

But a record has several fields with data in each one. How does all the data get stored in a single object?

The answer is that an object can have several attributes. An attribute is like a field in a record. It has a name and a value. So when Rails reads the description value from the record on the database, it stores it in the @ad.description attribute of the @ad object. The same thing for the id, the name, the seller-id, and so on.

In this way, the @ad model object exactly matches the record in the database. This is useful because this memory object will be visible to the view code.

The data’s in memory, and the web page can see it

The page template (show.html.erb) isn’t just sent straight back to the browser. First it gets processed by the Embedded Ruby program ERb, and that’s why our template had that .erb file extension. So let’s take a closer look at how ERb reads objects from memory.

ERb reads through the template looking for little pieces of embedded Ruby code called expressions. An expression is surrounded by <%= and %> and ERb will replace the expression with its value. So if it finds:

<%= 1 + 1 %>somewhere in the web page, Rails will replace this expression with 2 before returning the page to the browser.

But what we really want to do is get at the values in the @ad object from memory, like this:

Before sending the page back, Rails replaces all the <%=...%> tags with their object values.

So—does it work?

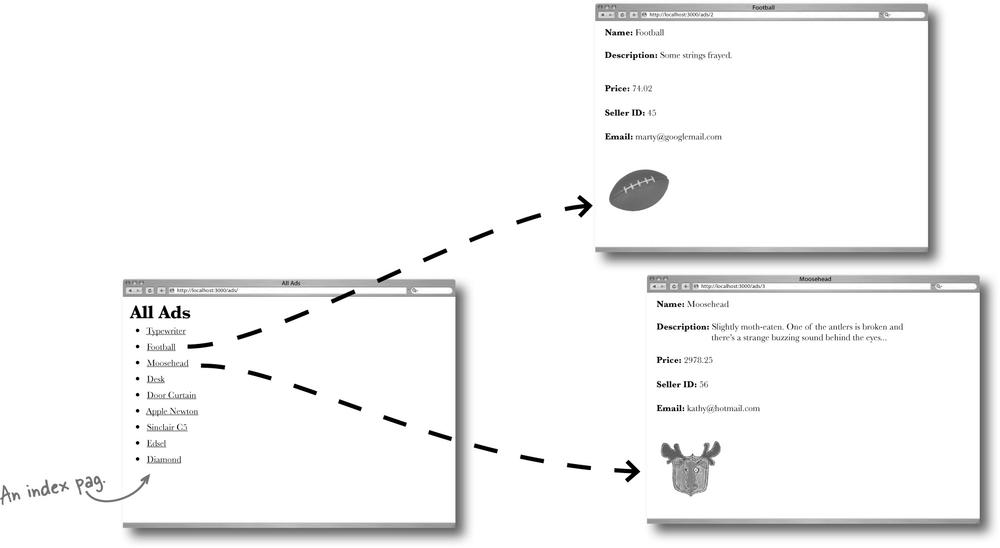

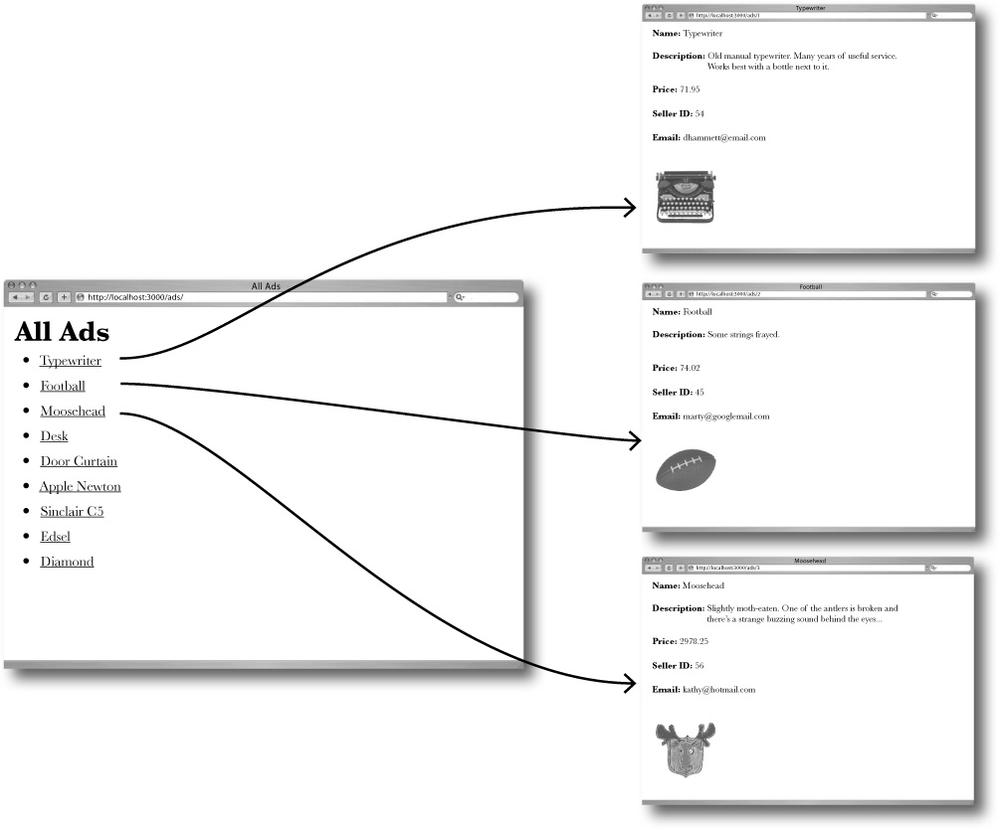

There’s a problem — people can’t find the pages they want

Even though there are pages for every ad in the database, there’s no easy way for people to find them.

To help people see what ads there are, and help them skip through the ads to find the ones that are interesting to them, the MeBay folks have asked for an index page to display links to all of the pages.

Routes run in priority order

Both of the routes match the /ads path. Rails avoids any ambiguity by only using the first matching route, so the routes need to be re-ordered to get rid of the confusion.

map.connect '/ads/', :controller=>'ads', :action=>'index' map.connect '/ads/:id', :controller=>'ads', :action=>'show'

These are the routes Rails will use. Now you need to complete the code.

To get data into the view, you will also need code in the controller

The model’s already in place, and there’s a route for the new controller code you need. But is there anything else?

Well, yes — you’ll need two things. The index page needs separate code in the controller because it’s looking at lots of ads, and you’ll need a new page to display that in the view.

But what else? What needs to happen to the controller?

An index page will need data from ALL of the records

The ad page only needed data from a single record, but what about the index page? That will need to read data from each of the records in the entire ads table. But why?

Look at the design for the index. It needs to create links for all of the ads pages, which means it will need to know the name and id number of every ad on the system.

But isn’t that a problem? So far we’ve only read single records at a time. Now we need to read a whole bunch of records all at once... in fact, we need all of the records.

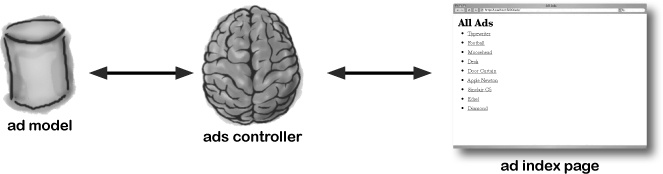

Ad.find(:all) reads the whole table at once

There’s another version of the Ad.find(...) finder method, which returns data about every record in the whole ads table:

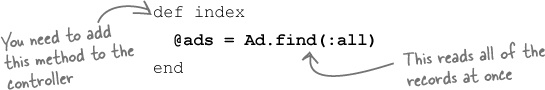

But how can that work? After all, when you were reading a single record, things were fairly simple. You passed the model an id number, and the model returned a single object containing all of the data in the row with the corresponding id.

But now you don’t know how many records you’re going to read. Won’t that mean you need some really horribly complex code?

Well, fortunately not. Rails makes reading every record in a table very similar to reading a single object. When you call Ad.find(:all), the model returns a single object that contains data for every record in the table. The controller can assign the object to a single variable.

But how can Rails store all of the data for an unknown number of rows inside a single object?

It does this by using a special type of object...

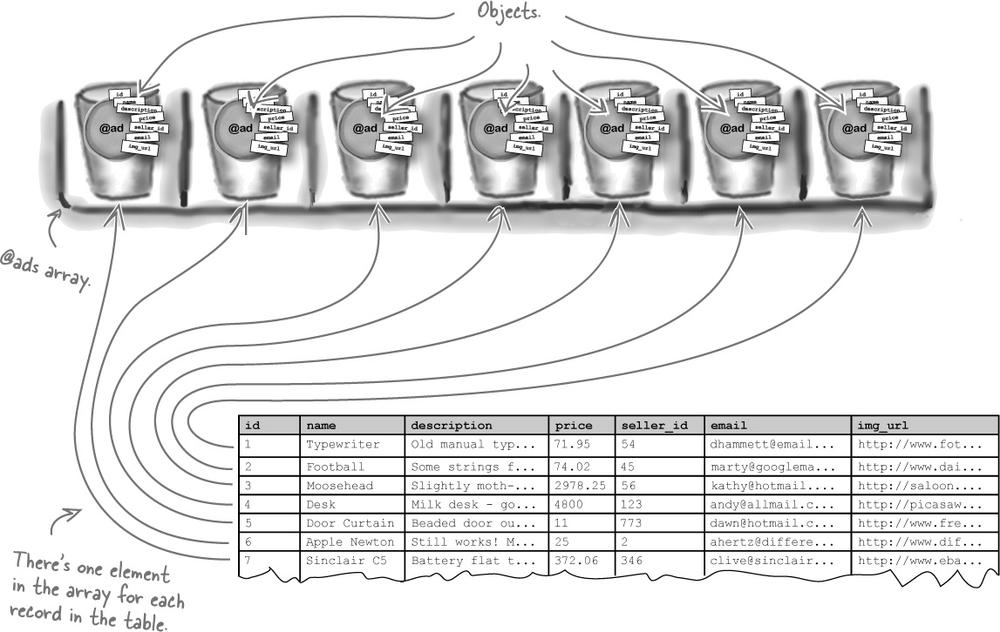

The data is returned as an object called an array

Rather than just return an object containing the data from a single record, the find method creates lots of objects—one for each record—and then wraps them up in an object called an array.

The Ad.find(:all) finder returns a single array object, that in turn contains as many model objects as there are rows in the database table.

The controller can store the single array object in memory with the name @ads. That makes it simpler for the page template, because instead of looking for an unknown number of model objects in memory, the template only needs to know the name of the array, to get access to all of the model objects.

But how do you get access to the objects, once they’re stored in the array?

An array is a numbered sequence of objects

The @ads array stores the model objects in a sequence of numbered slots, beginning with slot 0. The objects that are contained in each of the slots are called the array’s elements.

You can read the individual elements of the array by using the number of the slot that contains the element.

The slots are always numbered upwards from slot 0, and arrays can be as big as needed, so it doesn’t really matter how many records there are on the table, they can all be stored inside a single array object.

Watch it!

Arrays start at index 0

That means the position of each element is its index number plus one. So @ads[0] contains the first element, @ads[1] contains the second, and so on.

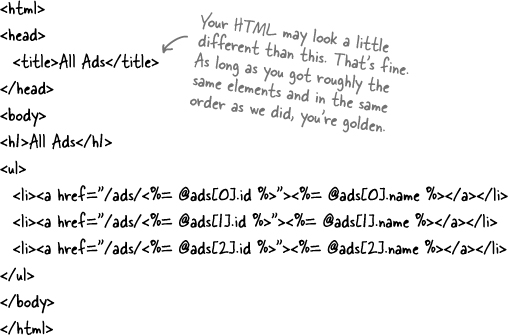

In practice, you won’t know how many ads there are.

The code above will only display 3 ads. But what if there are 4, or 5, or 3,000? You don’t want to have to change the template every time an ad is added or removed from the database.

You need some way of writing code that will cope with any number of ads in the database.

Read all of the ads with a for loop

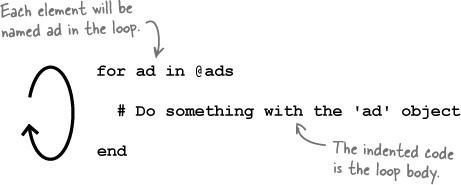

A Ruby for loop lets you run the same piece of Ruby code over and over again. It can be used to read the elements in an array, one at a time, and then run a piece of code on each element.

The piece of code that’s run each time is called the loop body. The loop body will execute for each element of the array, in sequence, starting with element 0:

In the above code, each time the body runs, the current element in the array is given the name ad. So ad refers to each of the Ad model objects, and inside the loop you can access all of the model objects attributes: the details of the ad, such as the name or the description of the thing being sold.

Right now, we need to generate the HTML that will create a link to the ad’s web page. But the HTML is generated by the page template. How can we use a for loop with that?

We need HTML for each element in the array

For each ad object in the @ads array, we need to generate a hyperlink in HTML.

We can use a for loop to do this. The loop would allow us to work through each of the ads, one at a time. If we used the loop body to generate the HTML, we could create links for each of the ads:

The problem is that we generate web pages by putting Ruby expressions inside page templates. The HTML in the page template controls when the Ruby expressions are called. But we want to do things the other way round. We want a Ruby for loop to control when the HTML is generated.

So how can we combine control statements like for loops with page template HTML?

Rails converts page templates into Ruby code

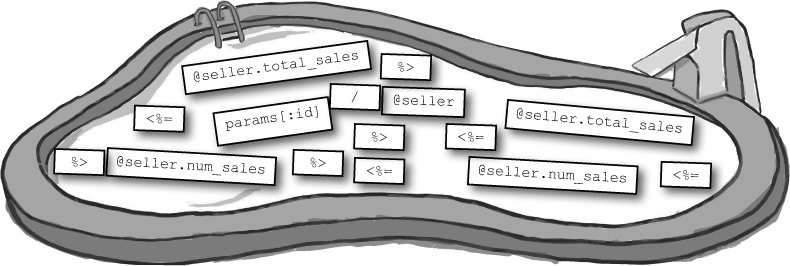

When we wanted to get object values into a page before, we inserted them using <%=...%>:

<%[email protected]%>ERb (Embedded Ruby) generates a web page from the template by replacing each of the expressions with their values. ERb does this by converting the entire page into Ruby code.

If you want a template to generate code for each object in an array, how would you want the Ruby code to look?

Loops can be added to page templates using scriptlets

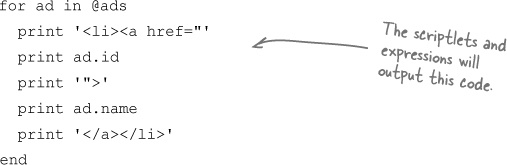

Let’s forget about page templates for the moment. If you were writing a piece of code to print out HTML for each element in an array, what would that code look like? It might look a little like this:

We need to loop through the array and print out HTML and expressions for each element. So far we’ve only seen ERb generating print commands, but the for loop isn’t a print command. So how can we pass ERb chunks of Ruby code—like the for loop?

The solution is to use scriptlets.

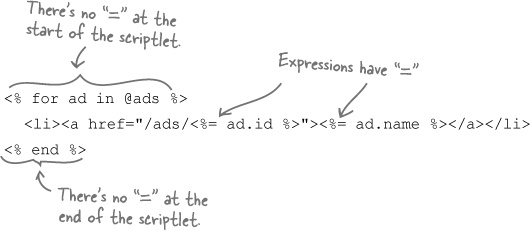

A scriplet is a tag containing a piece of Ruby code. Expression tags are surrounded by <%=... %>, but scriptlets are surrounded by <%...%>. Scriptlets don’t have the = sign at the start of them.

To see how scriptlets work, let’s take a look at a page template to produce the for loop code above:

This code uses scriptlets for the looping code and expressions where values will be inserted. Let’s see what the index page template will look like if we use scriptlets to loop through the @ads array.

On each pass of the loop, the page generates one link

This is the code you’ll be using for the index.html.erb template:

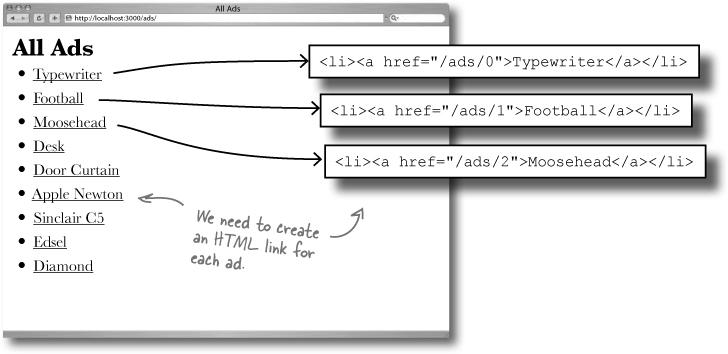

When Rails processes the template, the HTML at the top and the bottom of the file will just be output as you’d expect. The interesting part is in the middle of the page. Each pass of the loop will generate an HTML link to the matching ad page.

So what does the generated HTML look like?

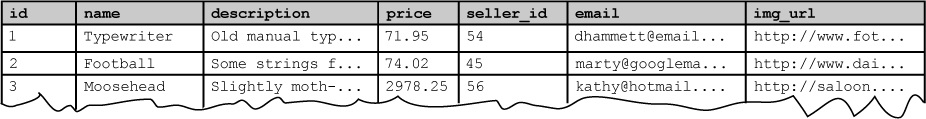

Imagine there are just these three ads in the database.

That means the controller will produce an @ads array containing three model objects. When the page template loops through the @ads array it should produce HTML that looks something like this:

So it looks like this will generate just enough HTML for all of the ads in the database. If there are more ads created in the database, a larger @ads array will be produced, and the template should generate a longer piece of HTML.

That’s the theory. Now that the route’s been created, the controller action’s been written, and the index.html.erb template’s in place it’s time to run the code.

You just got an email from the folks at MeBay...

The functionality of the site now matches exactly what the original spec asked for. Everyone’s really pleased. Then, on the morning that the site’s due to launch, you get an email:

Dude! |

You did an incredible job with the site. We’re really pleased at the way you were able to build it to our exact specification. We’d heard that Rails applications always looked and worked the same! |

By the way, here’s a design for how the site will look. We think this will be the final look of the application, but if there are any changes, we’ll send them through later. |

Thanks again for all the hard work :-) |

There’s a sample web page and a set of stylesheets and images attached to the email. It can’t be that hard to change the look of the application, can it?

But there are two page templates... should we change the code of each one?

There are two page templates, so if you just change the HTML in both templates to match the MeBay sample page, you’ll have duplicated the code. Is that really a big deal here? After all, there are only two types of web pages in the MeBay site. That’s not so bad, is it?

The problem is that the application may grow over time and acquire more features and page templates. And what about that comment about the design possibly changing? The more times you duplicate the look, the more places you have to maintain the same HTML. Over time the application could become hard work to maintain.

So what’s the answer? Well, the obvious answer is to remove the duplication. Most web sites have a standardized look across most of their pages. They have standard boilerplate HTML surrounding the main content of each page.

So you need some way of defining a super-template: one single template that will control how a group of other templates will look.

Rails Principle: DRY - Don’t Repeat Yourself.

A layout defines a STANDARD look for a whole set of page templates

Fortunately, just such a super-template exists in Rails, and it’s called a layout. A layout defines an HTML wrapper for all of the templates belonging to a particular model.

Let’s see how it’ll work with the new design.

You need to REMOVE the boilerplate from your page templates

Look at the existing index.html.erb. It already contains HTML boilerplate elements, like the <head> and the <title>:

<html> <head> <title>All Ads</title> </head> <body> <h1>All Ads</h1> <ul> <% for ad in @ads %> <li><a href="/ads/<%= ad.id %>"><%= ad.name %></a></li> <% end %> </ul> </body> </html> |

But now that there’s a layout providing the boilerplate, you need to cut down the templates so they display just the main page content:

But what about the new static content MeBay sent over?

So far you’ve only generated dynamic content from a Rails app. Pretty much everything has been output page templates. But when you’re specifying the cosmetics of a site, you often need static content like stylesheets, images, and JavaScripts. But how do you include static content in the application?

Rails sets aside a folder just for static files. It’s called public.

When you create the application, Rails already put quite a few files in the public folder. Remember the first time you started the Rails application and looked at the front page? The files for the standard welcome page all live in the public folder.

Most Rails applications store their images, stylesheets and JavaScripts in public/images, public/stylesheets and public/javascripts respectively.

Once you’ve saved the extra images and stylesheets from the email, we should be good to go.

Tools for your Rails Toolbox

You’ve got Chapter 2 under your belt, and now you’ve added the ability to manually create read-only applications to your toolbox.