3 Statute law

A Quick Guide to Statutes, Regulations, Approved Codes of Practice and Guidance Notes

Statutes

These, as we have seen, are Acts of Parliament, such as the Factories Act 1961, the Offices, Shops and Railway Premises Act 1963 and the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974.

Regulations

Most statutes give the Minister(s) power to make regulations (subordinate or delegated legislation) without referring the matter to Parliament. The regulations may be drafted by the HSE and submitted through the HSC to the Secretary of State or Minister, such as the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations 2002, the Noise at Work Regulations 1989, the Safety Representatives and Safety Committees Regulations 1977 and the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999.

There is a general requirement for the HSC and HSE to keep interested parties informed of, and adequately advised on, such matters.

Approved Codes of Practice (ACOPs)

The need to provide elaboration on the implementation of regulations is recognised in section 16 of the HSWA, which gives the HSC power to prepare and approve codes of practice on matters contained not only in regulations, but in sections 2 to 7 of the Act. Before approving a Code, the HSE, acting for the HSC, must consult with any interested body.

An ACOP is a quasi-legal document and, although non-compliance does not constitute a breach, if the contravention of the Act or regulations is alleged, the fact that the ACOP was not followed would be accepted in court as evidence of failure to do all that was reasonably practicable. A defence would be to prove that works of equivalent nature had been carried out or something equally good or better had been done.

Examples of ACOPs are Control of Asbestos at Work, Control of Substances Hazardous to Health, Protection of Persons against Ionising Radiation Arising From Any Work Activity and Safety of Pressure Systems.

HSE Guidance Notes

The HSE issues Guidance Notes in some cases to supplement the information in ACOPs. Such Guidance Notes have no legal status and are purely of an advisory nature.

HSE Guidance Notes fall into six categories:

• general safety (GS)

• chemical safety (CS)

• environmental hygiene (EH)

• medical series (MS)

• plant and machinery (PM)

• health and safety (Guidance) (HS(G)).

Examples of HSE Guidance Notes are:

EH40 Occupational Exposure Limits

MS20 Pre-employment Health Screening

HS(G)37 Introduction to Local Exhaust Ventilation

PM41 Application of Photoelectric Safety Systems to Machinery

GS20 Fire Precautions in Pressurised Workings.

The Parliamentary Process

Statutes

One of the main functions of Parliament is the enactment of statutes, or, Acts of Parliament.

Most statutes commence their lives as bills and most government-introduced bills start the Parliamentary process in the House of Commons (though some bills of a non-controversial nature may start in the House of Lords). The process in the House of Commons commences with a formal first reading. This is followed by a second reading, at which stage, there is discussion of the general principles and the bill’s main purpose. Following the second reading, the bill goes to the committee stage for detailed consideration by an appointed committee, comprising both Members of Parliament and specialists. After due consideration, the committee reports back to the House with recommendations for amendments. Such amendments are considered by the House and they, in turn, may make amendments at this stage and/or return the bill to the committee for further consideration. After this report stage, the bill receives a third reading where only verbal alterations are made.

The bill is then passed to the House of Lords where it goes through a similar process. The House of Lords either passes the bill or amends it. In the case of an amendment it is returned to the House of Commons for further consideration.

After a bill has been passed by both Houses, it receives the Royal Assent, which is always granted, and then becomes an Act of Parliament.

Regulations

A statute generally confers power on a Minister or Secretary of State to make statutory instruments, which may indicate more detailed rules or requirements for implementing the overall objectives of the statute. Most statutory instruments take the form of regulations and come within the area of law known as delegated or subordinate legislation.

The HSWA is an enabling Act. This means that, in the case of health and safety regulations, the Secretary of State for Employment has powers conferred under the HSWA (section 15, Schedule 3 and section 80) to make regulations on a wide variety of issues, but within the general objectives and aims of the parent Act. Examples of regulations made under the HSWA are the:

• Electricity at Work Regulations 1989

• Health and Safety (First Aid) Regulations 1981

• Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999.

Regulations may:

• repeal or modify existing statutory provisions

• exclude or modify the provisions of sections 2–9 of the HSWA or existing provisions in relation to any specified class

• make a specified authority, such as a local authority, responsible for enforcement

• impose approval requirements

• refer to specified documents to operate as references

• give exemptions

• specify the class of person who may be guilty of an offence, for example, employers

• apply to a particular case only.

The Principal Statutes in Force Before the Health and Safety at Work, etc. Act 1974

Prior to the HSWA, the principal health and safety legislation was contained in the Factories Act 1961, the Offices, Shops and Railway Premises Act 1963 and the Mines and Quarries Act 1954. Much of this legislation, including regulations made under these Acts, was repealed by subsequent statutes and regulations made under the HSWA, for instance the Fire Precautions Act 1971 and the Pressure Equipment Regulations 1999, the Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations 1992, the Provision and Use of Work Equipment Regulations 1998, and the Personal Protective Equipment at Work Regulations 1992 respectively (see also Chapter 4).

The Factories Act 1961

This Act is a consolidating Act as it brings together earlier separate pieces of legislation relating to health, safety and welfare in factories. It incorporates both general and specific provisions relating to working conditions, machinery safety, structural safety and the welfare of people working in factories.

Whilst much of the Factories Act 1961 (FA) has been repealed or revoked by the Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations 1992 (WHSWR) and the Provision and Use of Work Equipment Regulations 1998 (PUWER), the following remaining provisions are of importance.

• Section 20: Cleaning of machinery by young people This section requires that no young person shall clean any part of a prime mover or of any transmission machinery while the prime mover or transmission machinery is in motion, and shall not clean any part of any machine if the cleaning thereof would expose the young person to risk of injury from any moving part either of that machine or of any adjacent machinery.

• Section 21: Training and supervision of young people working at dangerous machines This section prohibits young people from working at any prescribed dangerous machine unless they have been fully instructed as to the dangers arising in connection with it and the precautions to be observed, and:

– have received sufficient training in work at the machine

– are under adequate supervision by a person who has thorough knowledge and experience of the machine.

• Section 30: Dangerous fumes and lack of oxygen This section is principally concerned with the hazards that may exist in confined spaces and the precautions necessary, such as the operation of a permit to work a system. A ‘confined space’ is defined as including any chamber, tank, vat, pit, pipe, flue or similar confined space and the following precautions must be taken:

– where there is no adequate means of egress from the confined space, a manhole must be provided of a minimum size

– a responsible person must certify that the space is safe to enter for a specified length of time without the need for breathing apparatus

– where the confined space is not certified as being safe, no one must enter or remain in the confined space unless they are wearing breathing apparatus, have authority to enter from a responsible person and, where practicable, are wearing belts with a rope securely attached and a person, keeping watch outside and capable of pulling them out, is holding the free end of the rope

– there must be sufficient trained people to use the breathing apparatus during the operation

– there is provided and kept readily available a sufficient supply of approved breathing apparatus, of belts and ropes, and of suitable reviving apparatus and oxygen, and the apparatus, belts and ropes shall be maintained and thoroughly examined at least once a month or at such other intervals as may be prescribed, by a competent person, and a report of every such examination, signed by the person making the examination and containing the prescribed particulars, shall be kept available for inspection

– a sufficient number of people employed shall be trained and practised in the use of the apparatus mentioned above and in reviving those who have stopped breathing

– no person shall enter or remain in any confined space in which the proportion of oxygen in the air is liable to have been substantially reduced unless either:

(i) they are wearing suitable breathing apparatus or

(ii) the space has been and remains adequately ventilated and a responsible person has tested and certified it as safe for entry without breathing apparatus

– no work shall be permitted in any boiler furnace or boiler flue unless it has been sufficiently cooled by ventilation or otherwise to make work safe for the persons employed.

• Section 31: Precautions with respect to explosive or inflammable dust, gas, vapour or substance Where, in connection with any grinding, sieving or other process giving rise to dust, there may escape dust of such a character and to such an extent as to be liable to explode on ignition, all practicable steps shall be taken to prevent such an explosion by enclosure of the plant used in the process, and by removal or prevention of accumulation of dust that may escape in spite of the enclosure, and by exclusion or effective enclosure of possible sources of ignition.

Where there is present in any plant used in any such process as aforesaid dust of such character and to such an extent as to be liable to explode on ignition, then, unless the plant is so constructed as to withstand the pressure likely to be produced by any such explosion, all practicable steps shall be taken to restrict the spread and effects of such an explosion by the provision in connection with the plant, of chokes, baffles and vents, or other equally effective appliances.

Where any part of a plant contains any explosive or inflammable gas or vapour under pressure greater than atmospheric pressure, that part shall not be opened, except in accordance with the following provisions:

– before the fastening of any joint of any pipe connected with the part of the plant or the fastening of the cover of any opening into the plant is loosened, any flow of the gas or vapour into the part or into any such pipe shall be effectively stopped by a stop-valve or otherwise

– before any such fastening is removed, all practicable steps shall be taken to reduce the pressure of the gas or vapour in the pipe or part of the plant to atmospheric pressure

and if any such fastening has been loosened or removed, no explosive or inflammable gas or vapour shall be allowed to enter the pipe or part of the plant until the fastening has been secured or, as the case may be, securely replaced, but nothing in this subsection applies to a plant installed in the open air.

No plant tank or vessel that contains, or has contained, any explosive or flammable substance shall be subjected:

– to any welding, brazing or soldering operation

– to any cutting operation that involves the application of heat

– to any operation involving the application of heat for the purpose of taking apart or removing the plant, tank or vessel or any part of it until all practicable steps have been taken to remove the substance and any fumes arising from it, or to render them non-explosive or non-inflammable. If any plant, tank or vessel has been subjected to any such operation, no explosive or inflammable substance shall be allowed to enter the plant, tank or vessel until the metal has cooled sufficiently to prevent any risk of igniting the substance.

• Section 34: Steam boilers (restrictions on entry) No person shall enter or be in any steam boiler that is one of a range of two or more steam boilers unless:

– all inlets through which steam or hot water might otherwise enter the boiler from any other part of the range are disconnected from that part

– all valves or taps controlling the entry of steam or hot water are closed and securely locked, and, where the boiler has a blow-off pipe in common with one or more other boilers or delivering into a common blow-off vessel or sump, the blow-off valve or tap on each boiler is so constructed that it can only be opened by a key that cannot be removed until the valve or tap is closed and is the only key in use for that set of blow-off valves or taps.

• Section 63: Removal of dust or fumes In every factory in which, in connection with any process carried on, there is given off any dust or fume or other impurity of such a character and to such an extent as to be likely to be injurious or offensive to the people employed, or any substantial quantity of dust of any kind, all practicable measures shall be taken to protect these people against inhalation of the dust or fume or other impurity and to prevent its accumulating in any workroom and, in particular, where the nature of the process makes it practicable, exhaust appliances shall be provided and maintained, as near as possible to the point of origin of the dust or fume or other impurity, so as to prevent it entering the air of any workroom.

No stationary internal combustion engine shall be used unless:

– provision is made for conducting the exhaust gases from the engine into the open air

– the engine (except when used for the purpose of being tested) is so partitioned from any workroom or part of a workroom in which people are employed, other than those attending to the engine, so as to prevent any injurious fumes from the engine entering the air of the room or part of the room.

Employment Rights Act 1996

Part V of the Employment Rights Act deals with ‘protection from suffering detriment in employment’. Section 44 covers the right not to suffer detriment in ‘health and safety cases’.

Health and safety cases

An employee has the right not to be subjected to any detriment by any act, or any deliberate failure to act, by his employer done on the ground that:

(a) having been designated by the employer to carry out activities in connection with preventing or reducing risks to health and safety at work, the employee carried out (or proposed to carry out) any such activities;

(b) being a representative of workers on matters relating to health and safety at work or a member of a safety committee:

(i) in accordance with arrangements established under or by virtue of any enactment; or

(ii) by reason of being acknowledged as such by the employer,

the employee performed (or proposed to perform) any functions as such a representative or a member of such a committee;

(c) being an employee at a place where:

(i) there was no such representative or safety committee; or

(ii) there was such a representative or safety committee but it was not reasonably practicable for the employee to raise the matter by those means,

he brought to his employer’s attention, by reasonable means, circumstances connected with his work which he reasonably believed were harmful or potentially harmful to health or safety;

(d) in circumstances of danger which the employee reasonably believed to be serious and imminent and which he could not reasonably have been expected to avert, he left (or proposed to leave) or (while the danger persisted) refused to return to his place of work or any dangerous part of his place of work; or

(e) in circumstances of danger which the employee reasonably believed to be serious and imminent, he took (or proposed to take) appropriate steps to protect himself or other persons from the danger.

For the purposes of sub-section (e) above, whether steps which an employee took (or proposed to take) were appropriate is to be judged by reference to all the circumstances including, in particular, his knowledge and the facilities and advice available to him at the time.

An employee is not to be regarded as having been subjected to any detriment on the ground specified in subsection (e) above if the employer shows that it was (or would have been) so negligent for the employee to take the steps which he took (or proposed to take) that a reasonable employer might have treated him as the employer did.

Children and Young People

A ‘child’ is a person under compulsory school-leaving age, which, at present, is under 16 years, while a ‘young person’ is someone who has ceased to be a ‘child’, but who is not yet 18 years old.

Health and Safety (Training for Employment) Regulations 1990

These regulations outline the requirements for protection of employees under the relevant statutory provisions with respect to the provision of ‘relevant training’.

Relevant training means work experience provided pursuant to a training course or programme, or training for employment, or both, except if:

(a) the immediate provider of the work experience or training for employment is an educational establishment and it is provided on a course run by the establishment; or

(b) received under a contract of employment.

The regulations extend the definition of ‘work’ under the HSWA to include relevant training (as defined).

Similarly, a person provided with relevant training shall be treated as being the employee of the person whose undertaking (whether carried on by him for profit or not) is for the time being the immediate provider to that person of the training.

Restrictions and prohibitions on the employment of young people

Under the FA 1961, specific requirements are laid down as regards:

• conditions and hours of work, that is, they should work a maximum of 9 hours per day, 48 hours in any week, or for young people under 16 years old, 44 hours a week

• periods of employment must not exceed 11 hours in one day, not begin before 7 am, nor end later than 8 pm, or 1 pm on Saturdays

• continuous employment, that is, a young person must not be employed for more than four and a half hours without an interval of at least half an hour for a meal break, and there must be a minimum ten-minute rest break per four and a half hours work period

• meals and rest breaks, that is, young people must not work during meal or rest periods

• holidays, that is, young people must not work on Sundays or public holidays as a rule, but subject to certain provisions

• shift work, that is, arrangements must be made with the HSE for all young people employed in factories to work on a shift system and then only within certain defined limits

• work involving machinery, that is, as mentioned above, no young person must work with specified machines unless fully instructed in the dangers of, and precautions to be taken with, them

• restrictions on employment in specific processes, for example, blasting operations.

The Offices, Shops and Railway Premises Act 1963

The WHSWR 1992 and PUWER 1992 revoked substantial parts of the Offices, Shops and Railway Premises Act 1963 (OSRPA). The following remaining provisions are of importance.

• Section 18: Exposure of young persons to danger in cleaning machinery No young person, that is someone under the age of 18, must clean any machinery if, by so doing, they expose themselves to risk of injury from it or any adjacent machinery

• Section 19: Training and supervision for working at dangerous machines No one shall work at any machine that is prescribed as dangerous, unless they have been fully instructed of the dangers arising in connection with it and the precautions to be observed and either have sufficient training in work at the machine or are under the supervision of a person who has thorough knowledge and experience of the machine

• Section 49: Notification Before work commences in offices or shops, the employer must notify the enforcing authority (local authority) on Form OSR1.

Fire Safety Legislation

The Fire Precautions Act (FPA) 1971, as amended by the Fire Safety and Safety of Places of Sport Act (FSSPSA) 1987, applies to all premises actually in use – industrial, commercial or public – and is enforced by the various fire authorities. Where premises incorporate intrinsically hazardous substances, such as the storage of flammable substances and explosives, control is exercised by the HSE. Fire safety legislation is principally concerned with ensuring the provision of:

• means of escape in the event of fire

• the means for fighting fire

and this is implemented by means of a process of fire certification.

The FPA required that a fire certificate be issued for certain classes of factory and commercial premises, based on the concept of designated use. The FSSPSA, in effect, deregulated many premises that formerly required certification under the FPA, including:

• factories, offices and shops where:

– more than 20 people are employed at any one time

– more than ten people are employed at any one time elsewhere than on the ground floor

– buildings containing two or more factory and/or office premises, where the aggregate of people employed in all of them at any one time is more than 20

– buildings containing two or more factory and/or office premises, where the aggregate of people employed at any one time in all of them, elsewhere than on the ground floor, is more than ten

– factories where explosive or highly flammable materials are stored, or used in or under the premises, unless, in the opinion of the fire authority, there was no serious risk to employees from fire

• hotels and boarding houses where there is sleeping accommodation provided for guest or staff:

– for six or more people

– at basement level

– above the first floor.

The effect of this deregulation was to exempt certain low-risk premises from the certification requirements. Thus, the FSSPSA empowers local fire authorities to grant exemptions in respect of certain medium-risk and low-risk premises that were previously ‘designated use’ premises. The exemption certificate must, however, specify the maximum number of persons who can safely be in or on the premises at any one time. Furthermore, the exemption can be withdrawn by the fire authority without prior inspection and by service of notice of withdrawal, where the degree of risk associated with the premises increases.

Fire Precautions Act 1971

• Section 5: Application for fire certificates Premises will require a fire certificate where they have not been granted an exemption under the FSSPSA. An application for a fire certificate should normally be made to the local fire authority on Form FP1, by the occupier in the case of factories, offices and shops. In certain cases, however, it must be made by the owner, thus:

– premises consisting of part of a building, all parts of which are owned by the same people, that is, multioccupied buildings in single ownership

– premises consisting of part of a building, the different parts being owned by different people, that is, multioccupied buildings with plural ownership.

An application must specify the premises concerned, the use to be covered and, if required by the fire authority, be supported within a specified time by plans of the premises. Before a fire certificate is issued, inspection of the premises is essential under the FPA. Where, following an inspection, the fire authority does not consider the premises safe against fire, they will normally require the occupier to carry out improvements before issuing a certificate.

• Section 6: Fire certificates A fire certificate specifies:

– the particular use or uses of the premises that it covers

– the means of escape in case of fire, indicated in a plan of the premises

– the means for securing that the means of escape can be safely and effectively used at all relevant times

– the means for fighting fire for use by persons in the premises

– the means for giving warnings in the case of fire

– particulars as to explosive or highly flammable liquids stored and used on the premises.

The fire certificate may also impose requirements relating to:

– the maintenance of the means of escape and keeping it free from obstruction

– the maintenance of other fire precautions outlined in the certificate

– the training of employees as to action in the event of fire and the maintenance of suitable records of such training

– limiting the number of people who, at any one time, may be on the premises

– any other relevant fire precautions.

A fire certificate, or a copy of same, must be kept in the building concerned.

• Section 8: Inspection of premises So long as a fire certificate is in force for any premises, the fire authority may cause inspections to be made from time to time to ascertain whether the requirements of the certificate are being maintained or are becoming inadequate.

Before carrying out any structural alterations or any material internal alterations to premises requiring a fire certificate, it is necessary, first, to notify the fire authority, or in the case of ‘special premises’, the HSE, of the proposed changes. Similar requirements apply in cases of proposed alterations to equipment or furniture on the premises. Following notification, the premises will be inspected before the alteration work can go ahead. Failure to follow this procedure is an offence under the FPA.

Fire Safety and Safety of Places of Sport Act 1987

Legal requirements relating to the fire certification of premises, as contained in the FPA, were modified by the FSSPSA. One of the main general purposes of the FSSPSA was to concentrate effort on premises where there is a high risk of fire, at the same time reducing the need for certification in the case of low-risk premises. The FSSPSA is, therefore, a deregulating measure. It empowers fire authorities to grant exemptions in respect of low-risk premises that were previously ‘designated use’ premises under the FPA and required a fire certificate. An occupier does not have to formally apply for such exemption. It may be granted either on application for a fire certificate or while a fire certificate is in force. Generally, however, premises would not be exempted unless they had been inspected within the previous 12 months. The consequence of this is that if an exemption is granted:

• on application for a fire certificate, it disposes of the application

• while the certificate is in force, the certificate no longer has any effect.

The exemption certificate must, however, specify the maximum number of people who can safely be in or on the premises at any one time. Depending on the relative degree of fire risk, the exemption can be withdrawn by the fire authority without prior inspection, on notice being given to the occupier of such a withdrawal.

The following sections of the FSSPSA are important.

• Section 5: Means of escape in case of fire Although low- or medium-risk premises may be exempt from certification under the FSSPSA, occupiers must still provide a means of escape and fire fighting equipment. ‘Escape’ is defined in the Act as ‘escape from premises to some place of safety beyond the building, which constitutes or comprises the premises, and any area enclosed by it or within it; accordingly, conditions or requirements can be imposed as respects any place or thing by means of which a person escapes from premises to a place of safety’.

• Section 8: Alterations to exempted premises An occupier who intends to carry out any material alterations to a premises while an exemption order is in force must first notify the fire authority of the proposed alterations. Failure to notify is an offence under the Act.

Notification is particularly necessary in cases where:

– the proposed extension of, and/or structural alteration to premises may affect the means of escape

– any alteration to the interior of the premises, in furniture or equipment, may affect the means of escape

– the proposed storage of explosive or highly flammable material in or on the premises in quantities/aggregate quantities is greater than that specified by the current certificate

– it is proposed that a greater number of people be on the premises than specified by the certificate.

Enforcement provisions of the FSSPSA

• Section 9: Improvement notices Where a fire authority is of the opinion that an occupier has not fulfilled their duty with regard to the provision of:

– means of escape in case of fire

– means for fighting fire

the authority may serve on the occupier an improvement notice, detailing the steps that should be taken in the way of improvements, alterations and other measures to remedy this breach of the Act. The occupier must normally undertake remedial work within 21 days, unless they submit an appeal against the notice. Such an appeal must be lodged within 21 days from the date of service of the notice, and it has the effect of suspending the operation of the notice. Where such an appeal fails, the occupier must undertake the remedial work specified in the improvement notice. Failure to do so can result in a fine on summary conviction and, on conviction, an indictment, an indefinite fine or imprisonment for up to two years, or both.

• Section 10: Prohibition notices Where there is considered to be a serious risk of injury to employees and visitors from fire on the premises, the fire authority can serve a prohibition notice on the occupier, requiring that remedial work be carried out in the interests of fire safety or, alternatively, have the premises closed down. The power to serve prohibition notices applies to all former ‘designated use’ premises, but not places of public religious worship or single private dwellings.

A prohibition notice may be served on premises:

– providing sleeping accommodation, such as hotels

– providing treatment/care, such as nursing homes

– for the purposes of entertainment, recreation or instruction, or for a club, society or association

– for teaching, training or research

– providing access to members of the public, whether for payment or otherwise

– which are places of work.

A prohibition notice is most likely to be served where means of escape are inadequate or non-existent or where there is a need to improve means of escape. As with a prohibition notice under the HSWA, such a notice can be served with immediate effect or deferred. An appeal does not suspend the operation of a prohibition notice.

Places of sport

The FSSPSA extends the existing Safety of Sports Grounds Act (SSGA) 1975, which only applied to sports stadia, that is, sports grounds where the accommodation for spectators wholly or substantially surrounds the activity taking place, to all forms of sports ground.

The legal situation relating to sports grounds under the FSSPSA is as follows:

• a general safety certificate is required for any sports ground

• the SSGA is extended to any sports ground that the Secretary of State considers appropriate

• the validity of safety certificates no longer requires the provision at a sports ground of a police presence, unless consent has been given by a chief constable or chief police officer

• there is provision for the service of prohibition notices in the case of serious risk of injury to spectators, prohibiting or restricting the admission of spectators in general or on specified occasions.

Prohibition notices

A prohibition notice may specify steps that must be taken to reduce risk, particularly from a fire, to a reasonable level, including structural alterations (irrespective of whether or not this may contravene the terms of a safety certificate for the ground issued by the local authority, or for any stand at the ground; see the next section, Safety certificates). Where a prohibition notice requires the provision of a police force, such requirements cannot be specified without the consent of the chief constable or chief police officer.

Under section 23 of the FSSPSA, a prohibition notice may be served on any of the following people:

• the holder of a general safety certificate

• the holder of a specific safety certificate, that is, a safety certificate for a specific sporting activity or occasion

• where no safety certificate is in operation, the management of the sports ground

• in the case of a specific sporting activity for which no safety certificate is in operation, the organisers of the activity

• where a general safety certificate is in operation for a stand at a ground, the holder of this certificate

• where a specific safety certificate is in operation for a stand, the holder of the certificate.

Under section 25 of the FSSPSA, sports grounds must be inspected at least once a year.

Safety certificates

Where a sports ground provides covered accommodation in stands for spectators, a safety certificate, issued by the local authority, is required for each stand providing covered accommodation for 500 or more spectators, that is, a regulated stand. In certain cases, safety certificates may be required for stands accommodating smaller numbers.

Records

Section 27 of the Act gives the local authority power to require the keeping of the following records in the case of stands at sports grounds:

• the number of spectators in covered accommodation

• procedures relating to the maintenance of safety in the stand.

Sports grounds with regulated stands must be inspected periodically.

Offences under the FSSPSA

The principal criminal offences under the Act are committed in respect of regulated stands when:

• spectators are admitted to a regulated stand at a sports ground on an occasion when a safety certificate should be, but is not, in operation

• any term or condition of a safety certificate for a regulated stand at a sports ground is contravened.

Both the management of the sports ground and, in the second case, the holder of the certificate, are guilty of an offence (section 36).

Under section 36 of the FSSPSA, a number of defences are available, namely:

• that either:

– the spectators were admitted when no safety certificate was in operation

– the contravention of the safety certificate occurred without their consent

• that they took all reasonable precautions and exercised all due care to avoid the offence being committed either by themselves or by people under their control.

Where a person or corporate body is charged with an offence under section 36, that is they had no safety certificate for a regulated stand, the defendant may plead that they did not know that the stand had been designated as being a regulated stand.

The Health and Safety at Work, etc. Act 1974

This Act covers all people at work, except domestic workers in private employment, whether they be employers, employees or the self-employed. It is aimed at people and their activities, rather than premises and processes.

The legislation includes provisions for both the protection of people at work and the prevention of risks of the health and safety of the general public that may arise from work activities.

The objectives of HSWA

These are:

• to secure the health, safety and welfare of all people at work

• to protect others from the risks arising from workplace activities

• to control the obtaining, keeping and use of explosive or highly flammable substances

• to control emissions into the atmosphere of noxious or offensive substances.

Specific duties

• Section 2: General duties of employers to their employees It is the duty of every employer, so far as is reasonably practicable, to ensure the health, safety and welfare at work of all their employees. More particularly, this includes:

– the provision and maintenance of plant and systems of work that are, so far as is reasonably practicable, safe and without risk to health

– arrangements for ensuring, so far as is reasonably practicable, safety and absence of risk to health in connection with the use, handling, storage and transport of articles and substances

– the provision of such information, instruction training and supervision as is necessary to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health and safety at work of employees

– so far as is reasonably practicable as regards any place of work under the employer’s control, the maintenance of it in a condition that is safe and without risk to health and the provision and maintenance of means of access to and egress from it that are safe and without such risk

– the provision and maintenance of a working environment for their employees that is, so far as is reasonably practicable, safe, without risk to health, and adequate as regards facilities and arrangements for their welfare at work.

Employers must prepare and, as often as is necessary, revise a written Statement of Health and Safety Policy, and bring the Statement and any revision of it to the notice of all their employees.

Every employer must also consult appointed safety representatives with a view to making and maintaining arrangements that will enable them and their employees to co-operate effectively in promoting and developing measures to ensure the health and safety at work of the employees, and in checking the effectiveness of such measures.

• Section 3: General duties of employers and the self-employed to people other than their employees Every employer must conduct their undertaking in such a way as to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that people not in their employ who may be affected by the business are not exposed to risks to their health or safety. (Similar duties are imposed on the self-employed.)

Every employer and self-employed person must give to others (those not in their employ) who may be affected by the way in which they conduct their business the prescribed information about such aspects of the way in which they work that might affect their health and safety.

• Section 4: General duties of people concerned with premises to people other than their employees This section has the effect of imposing duties in relation to those who:

– are not their employees, but

– use non-domestic premises made available to them as a place of work.

Every person who has, to any extent, control of premises must ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that the premises, all means of access to it or egress from it, and any plant or substances on the premises or provided for use there, is or are safe and without risk to health.

• Section 5: The general duty of people in control of certain premises in relation to harmful emissions into the atmosphere Any person having control of any premises of a class prescribed for the purposes of section 1(1)(d) must use the best practicable means for preventing the emission into the atmosphere from the premises of noxious or offensive substances and for rendering harmless and inoffensive such substances as may be emitted.

• Section 6: General duties of manufacturers and so on regarding articles and substances for use at work Any person who designs, manufactures, imports or supplies any article for use at work:

– must ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that the article is so designed and constructed as to be safe and without risk to health when properly used

– must carry out or arrange for the carrying out of such testing and examination as may be necessary to comply with the above duty

– must provide adequate information about the use for which it is designed and has been tested to ensure that, when put to that use, it will be safe and without risk to health.

Any person who undertakes the design or manufacture of any article for use at work must carry out or arrange for the carrying out of any necessary research with a view to the discovery and, so far as is reasonably practicable, the elimination or minimising of any risk to health or safety that the design or article may pose.

Any person who erects or installs any article for use at work must ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that nothing about the way it is erected or installed makes it unsafe or a risk to health when properly used.

Any person who manufactures, imports or supplies any substance for use at work:

– must ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that the substance is safe and without risk to health when properly used

– must carry out or arrange for the carrying out of such testing and examination as may be necessary

– must take such steps as are necessary to ensure adequate information about the results of any relevant tests is available in connection with the use of the substance at work.

• Section 7: General duties of employees at work It is the duty of every employee while at work:

– to take reasonable care for the health and safety of themselves and of others who may be affected by their acts or omissions at work

– as regards any duty or requirement imposed on their employer, to cooperate with them so far as is necessary to enable that duty or requirement to be performed or complied with.

• Section 8: The duty not to interfere with or misuse things supplied pursuant to certain provisions No one shall intentionally or recklessly interfere with or misuse anything provided in the interests of health, safety or welfare in order to satisfy any of the relevant statutory provisions.

• Section 9: The duty not to charge employees for things done or provided pursuant to certain specific requirements No employer shall levy or permit to be levied on any employee of theirs any charge in respect of anything done or provided in order to comply with any specific requirement of the relevant statutory provisions.

Corporate Liability, Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Killing

Corporate liability

Under the HSWA directors, managers, company secretaries and similar officers of the body corporate have both general and specific duties. Breaches of these duties can result in individuals being prosecuted.

Offences committed by companies (section 37(1))

Where a breach of one of the relevant statutory provisions on the part of a body corporate is proved to have been committed with the consent or connivance of, or to have been attributable to any neglect on the part of, any director, manager, secretary or other similar officer of the body corporate or a person who was purporting to act in any such capacity, he as well as the body corporate shall be guilty of that offence and shall be liable to be proceeded against and punished accordingly.

Breach of this section has the following outcomes:

1. Where an offence is committed through neglect by a board of directors, the company itself can be prosecuted as well as the directors individually who may have been to blame.

2. Where an individual functional director is guilty of an offence, he can be prosecuted as well as the company.

3. A company can be prosecuted even though the act or omission was committed by a junior official or executive or even a visitor to the company.

Generally, most prosecutions under section 37(1) would be limited to that body of persons, i.e. the board of directors and individual functional directors, as well as senior managers.

Offences committed by other corporate persons (section 36)

Section 36 makes provision for dealing with offences committed by corporate officials, e.g. personnel managers, health and safety specialists, training officers, etc. Thus:

Where the commission by any person of an offence under any of the relevant statutory provisions is due to the act or default of some other person, that other person shall be guilty of the offence, and a person may be charged with and convicted of the offence by virtue of this subsection whether or not proceedings are taken against the first mentioned person.

Corporate manslaughter

Manslaughter is of two kinds, that is, voluntary and involuntary. The former, which is essentially murder but reduced in severity owing to, say, diminished responsibility, is not relevant to health and safety. Involuntary manslaughter extends to all unlawful homicides where there is no malice aforethought or intent to kill.

There are two forms of involuntary manslaughter, that is, constructive manslaughter and reckless manslaughter. The former applies to situations where death results from an act unlawful at common law or by statute, amounting to more than mere negligence. Reckless manslaughter or gross negligence arises where death is caused by a reckless act or omission, and a person acts recklessly ‘without having given any thought to the possibility of there being any such risk or, having recognised that there was some risk involved, has none the less gone on to take it’ (R. v. Caldwell (1981) 1 AER 961).

Corporate killing

An offence of ‘corporate killing’ to make it easier to punish companies whose blameworthy conduct causes the death of employees or members of the public was proposed by the Law Commission in a report to Parliament on 5 March 1996.

The Commission recommended that corporations should be liable to an unlimited fine and that judges should have power to order them to remedy the cause of the death.

This situation arose following a number of disasters for which no successful prosecutions for manslaughter were brought, even though corporate bodies were found to be at fault. Examples include the King’s Cross fire, the Piper Alpha disaster and the Clapham rail crash. The main reason for the lack of successful prosecutions was that, under the present law, corporate manslaughter charges can only be brought where the corporation has acted through the ‘controlling mind’ of one of its agents, said the Commission. In practice it was often not possible to identify one person who has been the ‘controlling mind’. As a result, there had been only four prosecutions for corporate manslaughter and one conviction. In that case, the firm had been a ‘one man company’, so it was easy to identify the ‘controlling mind’.

The Law Commission said that it saw no reason why companies should continue to be effectively exempt from the law of manslaughter. The report also recommended that the present offence of involuntary manslaughter should be replaced with two new offences of reckless killing and killing by gross carelessness.

The Social Security Act 1975

Under this legislation:

• employees must notify their employer of any accident resulting in personal injury in respect of which benefit may be payable (notification may be given by a third party if the employee is incapacitated)

• employees must enter the appropriate particulars of all accidents in an accident book (Form BI 510), which may be done by another person if the employee is incapacitated; such an entry is deemed to satisfy the requirements given in the first point above

• employers must investigate all accidents of which notice is given by employees and any variations between the findings of this investigation and the particulars given in the notification must be recorded

• employers must, on request, furnish the Department of Social Security with such information as may be required relating to accidents in respect of which benefit may be payable, such as Forms 2508 and 2508A

• employers must provide and keep readily available an accident book in an approved form in which the appropriate details of all accidents can be recorded (Form BI 510) and such books, when completed, should be retained for three years after the date of the last entry

• for the purposes of the above, the appropriate particulars should include:

– name and address of the injured person

– date and time of the accident

– the place where the accident happened

– the cause and nature of the injury

– the name and address of any third party giving the notice.

The Consumer Protection Act 1987

This Act implements in the UK the provisions of the EC Directive of 25 July 1985 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the member states concerning liability for defective products.

• consolidates, with amendments, the Consumer Safety Act 1978 and the Consumer Safety (Amendment) Act 1986

• makes provision with respect to the giving of price indications

• amends Part I of the HSWA and sections 31 and 80 of the Explosives Act 1975

• repeals the Trade Descriptions Act 1972 and the Fabrics (Misdescription) Act 1913.

Part I, which deals with product liability, is significant from a health and safety viewpoint.

Part I: Product liability

Some important definitions

Within the context of Part I, a number of definitions are of significance. For example, producer in relation to a product means the following:

• the person who manufactured it

• in the case of a substance that has not been manufactured, but has been won or abstracted, the person who won or abstracted it

• in the case of a product that has not been manufactured, won or abstracted, for which the essential characteristics are attributable to an industrial process having been carried out, such as in relation to agricultural produce, the person who carried out that process.

Product means any goods or electricity and (subject to the proviso below) includes products that are used in another product, whether by virtue of being a component part or raw material for it or otherwise. The proviso is that a person who supplies any product in which products are used whether by virtue of being component parts or raw materials or otherwise, shall not be treated by reason only of their supply of that product, but as supplying any of the products so comprised.

Liability for defective products (section 2)

Where any damage is caused wholly or partly as a result of there being a defect in a product, all of the following people shall be liable for the damage:

• the producer of the product

• any person who, by putting their name on the product or using a trade mark or other distinguishing mark in relation to the product, has held themselves out to be the producer of the product

• any person who has imported the product into a Member State from a place other than one of the Member States in order, in the course of a business of theirs to supply it to another.

Where any damage is caused wholly or partly as a result of a defect in a product, any person who supplied the product (whether to the person who suffered damage, to the producer of any product in which the product in question is a part or to any other person) shall be liable for the damage if:

• the person who suffered the damage requests the supplier to identify one or more of the people (whether still in existence or not) detailed in the list above in relation to the product

• this request is made within a reasonable period after the damage occurs and at a time when it is not reasonably practicable for the person making the request to identify all these people

• the supplier fails within a reasonable period after receiving the request, either to comply with the request or to identify the person who supplied the product to them.

The meaning of ‘defect’ (section 3)

Subject to the following provisions, there is a defect in a product if the safety of the product is not of the kind one would generally be entitled to expect. For those purposes safety, in relation to a product, shall include safety with respect to products used in that product and safety in the context of any risks of damage to property, as well as in the context of risks of death or personal injury.

In determining what people are generally entitled to expect in relation to a product, all the circumstances shall be taken into account, including:

• the manner in which, and the purposes for which, the product has been marketed, its get-up, the use of any mark in relation to the product and any instructions for, or warnings with respect to doing or refraining from doing anything with or in relation to the product

• what might reasonably be expected to be done with or in relation to the product

• the time when the product was supplied by its producer to another

and nothing in this section requires a defect to be inferred, on its own, from the fact that the safety of a product that is supplied after that time is greater than the safety of the product in question.

Defences (section 4)

In any civil proceedings against any person (‘the person proceeded against’) in respect of a defect in a product, it shall be a defence if they can show that:

• the defect is attributable to compliance with any requirement imposed by or under any enactment or with any Community obligation

• that the person proceeded against did not at any time supply the product to another

• that the following conditions are satisfied:

– that the only supply of the product to another by the person proceeded against was otherwise than in the course of a business of that person’s

– that section 2 above does not apply to that person or applies to them by virtue only of things done otherwise than with a view to profit

• that the defect did not exist in the product at the relevant time

• that the state of scientific or technical knowledge at the relevant time was not such that a producer of products of the kind in question might have been expected to have discovered the defect in the products while they were under their control (‘state of the art’ defence)

• that the defect:

– constituted a defect in a product (‘the subsequent product’) of which the product in question was a part

– was wholly attributable either to the design of the subsequent products or to compliance by the producer of the product in question with instructions given to them by the producer of the subsequent product.

Damage giving rise to liability (section 5)

Subject to the following provisions, by the word damage is meant death or personal injury or any loss of or damage to any property (including land).

A person shall not be liable under section 2 for any defect in a product, for the loss or damage to the product itself or for the loss or damage to the whole or part of any product if it has been supplied as part of another product.

A person shall not be liable under section 2 for any loss of or damage to any property that, at the time it is lost or damaged, is not:

• ordinarily intended for private use, occupation or consumption

• intended by the person suffering the loss or damage mainly for their own private use, occupation or consumption.

No damages shall be awarded to any person under Part I regarding any loss of or damage to any property if the amount that would be so awarded apart from this subsection and any liability for interest, does not exceed £275.

In determining, for the purposes of this Part, who has suffered any loss or damage to property and when any such loss occurred, the loss or damage shall be regarded as having occurred at the earliest time at which a person with an interest in the property had knowledge of the material facts regarding any loss or damage.

For the purposes of the above subsection, the material facts regarding any loss of or damage to any property are those that relate to the kind of loss or damage that would lead a reasonable person with an interest in the property to consider the matter sufficiently serious as to justify their instituting proceedings for damages against a defendant who did not dispute liability and was able to satisfy a judgment.

By a person’s knowledge is meant knowledge that the person might reasonably have been expected to acquire:

• from the facts observable or ascertainable by this person

• from facts ascertainable by the person with the help of appropriate expert advice that it is reasonable to seek

but a person shall not be taken (by virtue of this subsection) to have knowledge of a fact ascertainable by them only with the help of expert advice unless they have failed to take all reasonable steps to obtain (and, where appropriate, act on) that advice.

Prohibition on exclusion from liability (section 7)

The liability of a person by virtue of this Part to a person who has suffered damage caused wholly or partly as a result of a defect in a product, or to a dependant or relative of such a person, shall not be limited or excluded by any contract term, by any notice or by any other provisions. By ‘notice’ is meant notice in writing.

Part II: Consumer safety

Part II deals with a general safety requirement, that making it an offence to supply unsafe consumer goods. This provision supplements certain provisions of the Consumer Safety Act 1978 providing coverage where there are no specific safety regulations under that Act.

Note that although the general safety requirement of Part II is restricted to consumer goods, section 6 of the HSWA applies in respect of the safety of articles and substances used at work. Also, Part I of the Act is not restricted to consumer goods – it can apply to anything described as a product.

The Environmental Protection Act 1990 (EPA)

The EPA brought in fundamental changes regarding the control of pollution and the protection of the environment. It repealed completely the Alkali, etc. Works Regulations Act 1906 and the Public Health (Recurring Nuisances) Act 1969, and certain sections of the well-established environmental protection legislation, such as the Public Health Acts 1936 and 1961, Control of Pollution Act 1954 and the Clean Air Act 1956. The Act covers eight specific aspects, namely:

• integrated pollution control and air pollution control by local authorities (Part I)

• waste on land (Part II)

• statutory nuisance and clean air (Part III)

• litter (Part IV)

• amendments to the Radioactive Substances Act 1960 (Part V)

• genetically modified organisms (Part VI)

• nature conservation (Part VII)

• miscellaneous provisions, for instance relating to the control of stray dogs and stubble burning (Part VIII).

Part I: Integrated pollution control and air pollution control by local authorities

A number of terms are of significance in the interpretation of this Part of the EPA:

• environment consists of all, or any, of the mediums of the air, water and land (and the medium of air includes the air within buildings and other natural or man-made structures above or below ground)

• pollution of the environment means pollution of the environment due to the release (into any environmental medium), from any process, of substances that are capable of causing harm to human beings or any other living organisms supported by the environment

• harm means harm to the health of living organisms or other interference with the ecological systems of which they form part and, in the case of humans includes offence caused to any of their senses or their property (harmless has a corresponding meaning)

• process means any activities carried out in Great Britain, whether on premises or by means of mobile plant, that are capable of causing pollution of the environment, and prescribed process means a process prescribed under section 2(1)

• authorisation means an authorisation for a process (whether on premises or by means of mobile plant) granted under section 6; and a reference to the conditions of an authorisation is a reference to the conditions subject to which, at any time, the authorisation has effect

• a substance is released into any environmental medium whenever it is released directly into that medium, whether it is released into it within or outside Great Britain, and release includes:

– in relation to air, any emission of the substance into the air

– in relation to water, any entry (including any discharge) of the substance into water

– in relation to land, any deposit, keeping or disposal of the substance in or on land.

Part 1 of the EPA identifies industrial processes that are scheduled for control either by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Pollution (HMIP) or by local authorities (LAs). Industrial processes are split into a two-part schedule for the purposes of enforcement.

Category A processes are subject to integrated pollution control (IPC) by HMIP. IPC applies the principle of best practicable environmental option (BPEO), and Category A processes have controls applied to all waste streams. BPEO is not defined in the Act, but was considered at length by the Royal Commission on Environmental Protection, whose definition is as follows:

A BPEO is the outcome of a systematic consultative and decision making procedure which emphasises the protection and conservation of the environment across land, air and water. The BPEO procedure establishes, for a given set of objectives, the option that proves the most benefit or least damage to the environment as a whole, at acceptable cost, in the long term as well as in the short term.

IPC covers waste streams in to the air, water and land. The general approach is to minimise these waste streams to ensure that the BPEO for the process is applied. Authorisations and controls are applied to all emissions (section 7). Fundamentally, the approach hinges on a prior authorisation procedure. Authorisations for industrial processes can have stringent conditions applied to them and these conditions apply the concept of the use of best available techniques not entailing excessive costs (BATNEEC). The primary objective of this concept is that of minimising pollution, or predicted pollution, of the environment as a whole from an industrial process. In other words, having regard to the BPEO (section 7(2)) the BATNEEC concept specifies the objectives to be considered in the conditions of authorisation as:

• ensuring that, in carrying out a prescribed process, the best available techniques not entailing excessive cost will be used:

– for preventing the release of substances prescribed for any environmental medium into that medium or, where this is not practicable by such means, for reducing the release of such substances to a minimum and for rendering harmless any such substances that are so released

– for rendering harmless any other substances that might cause harm if released into any environmental medium

• compliance with any directions that the Secretary of State has given for the implementation of any obligations in the United Kingdom under the Community Treaties or international law relating to environmental protection

• compliance with any limits or requirements and achievements of any quality standards or quality objectives prescribed by the Secretary of State under any of the relevant enactments

• compliance with any requirements applicable to the granting of authorisations specified by or under a plan made by the Secretary of State.

Those processes identified as Category B industrial processes are subject to a similar prior authorisation procedure administered by the LA’s environmental health department for discharges into the air only. Processes discharging substances in to water are regulated by the National Rivers Authority’s (NRA) discharge consent procedure and discharges into land are controlled by the Waste Regulation Authority (WRA), using controls detailed in Part II of the Act. Liaison between central and local government inspectorates is maintained through HMIP.

Under Part I of the Act, enforcing authorities must establish and maintain public information registers that contain details of the authorisations given for, and conditions applied to, processes.

Enforcement arrangements

Section 13 of the EPA states that where the enforcing authority is of the opinion that the person carrying on a prescribed process under an authorisation is contravening any condition of that authorisation, or is likely to contravene any such conditions, the authority may serve an enforcement notice.

An enforcement notice shall:

• state that the authority is of the said opinion

• specify the matters constituting the contravention or the matters making it likely that the contravention will arise, as the case may be

• specify the steps that must be taken to remedy the contravention or to remedy the matters that make it likely that the contravention will arise, whichever is relevant in the circumstances

• specify the period within which these steps must be taken.

Section 14 of the EPA makes provision for the service of prohibition notices. If the enforcing authority is of the opinion, as respects the carrying out of a prescribed process under an authorisation, that to continue to carry it out or to do so in a particular manner, involves an imminent risk of serious pollution of the environment, the authority shall serve a prohibition notice on the person carrying out the process.

A prohibition notice may be served whether or not the manner of carrying out the process in question contravenes a condition of the authorisation and may relate to any aspects of the process, whether these are regulated by conditions of the authorisation or not.

A prohibition notice shall:

• state the authority’s opinion

• specify the risk involved in the process

• specify the steps that must be taken to remove it and the period of time in which they must be taken

• direct that the authorisation shall, until the notice is withdrawn, wholly or to the extent specified in the notice, cease to authorise the carrying out of the process.

Also, where the direction applies to only part of the process, it may impose conditions to be observed in the carrying out of the part that is authorised to continue to be carried out.

Section 17 provides inspectors appointed under the EPA with considerable powers regarding premises on which a prescribed process is, or is believed to be, carried out and to those on which a prescribed process has been carried out, the condition of which is believed to pose a risk of serious pollution of the environment. Such powers include those of being able to:

• enter premises at any reasonable time if there is reason to believe that a prescribed process is or has been carried out that is or will give rise to a risk of serious pollution

• take a constable where obstruction on entry is anticipated, plus any necessary equipment or materials

• make such examinations and investigations as may be necessary

• direct that premises, or any part of the premises, remain undisturbed

• take measurements and photographs and make such recordings as are considered necessary

• take samples of articles and substances, and of air, water or land

• cause any article or substance that has caused, or is likely to cause, pollution to be dismantled or subjected to any process or test

• take possession of and detain any above article or substance for the purpose of examination, to ensure it is not tampered with before examination and is available for use as evidence

• require any person to answer questions as the inspector thinks fit and sign a declaration that their answers are the truth

• require the production of written or computerised records and take copies of these

• require that any person provide the facilities and assistance necessary to enable them to exercise their powers

• any other power conferred on them by the regulations.

Part II: Waste on land

The EPA imposes a duty of care on anyone who imports, carries, keeps, treats or disposes of waste. Such people must take all reasonable steps to ensure that the waste is collected, transported, treated and disposed of by licensed operators, that is, those issued with a waste management licence.

Public registers must be maintained by the authorities that detail the conditions of the licences issued and details of any enforcement actions taken. This Part should be read in conjunction with the system for IPC that is enforced by HMIP on prescribed Category A process industries.

Part III: Statutory nuisances and clean air

Section 79 deals with statutory nuisances and inspections. The following matters constitute statutory nuisance:

• any premises that are in such a state as to be prejudicial to health or cause a nuisance

• smoke emitted from premises that is prejudicial to health or causes a nuisance

• fumes or gases emitted from premises that are prejudicial to health or cause a nuisance

• any dust, steam, smell or other effluent arising on industrial, trade or business premises that are prejudicial to health or cause a nuisance

• any accumulation or deposit that is prejudicial to health or causes a nuisance

• any animal kept in a place or manner that is prejudicial to health or causes a nuisance

• noise emitted from premises that is prejudicial to health or causes a nuisance

• any other matter that is declared by any enactment to be a statutory nuisance.

It shall be the duty of every LA to ensure that its area is inspected from time to time to detect any statutory nuisances that ought to be dealt with under section 80 (Summary proceedings for statutory nuisances) and, where a complaint of a statutory nuisance is made to it by a person living within its area, to take such steps as are reasonably practicable to investigate the complaint. Where an LA is satisfied that a statutory nuisance exists, or is likely to occur or recur, that is in the area of the authority, the LA shall serve an abatement notice, imposing all or any of the following requirements:

• requiring the abatement of the nuisance or prohibiting or restricting its occurrence or recurrence

• requiring the execution of any works, and the taking of other steps, that may be necessary for any of these purposes

and the notice shall specify the time or times within which the requirements of the notice are to be complied with. Such a notice shall be served:

• except in the next two cases below, on the person responsible for the nuisance

• where the nuisance arises from any defect of a structural character, on the owner of the premises

• where the person responsible for the nuisance cannot be found or the nuisance has not yet occurred, on the owner or occupier of the premises.

A person served with an abatement notice may appeal to a Magistrates’ Court within 21 days, beginning with the date on which they were served with the notice. If a person is served an abatement notice and, without reasonable cause, contravenes or fails to comply with any requirement or prohibition imposed by the notice, they shall be guilty of an offence.

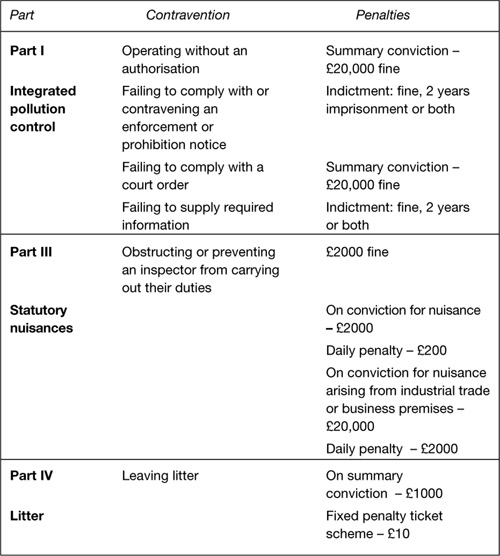

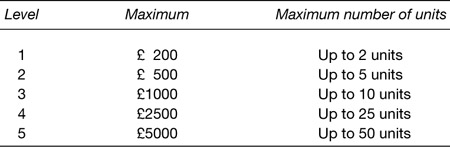

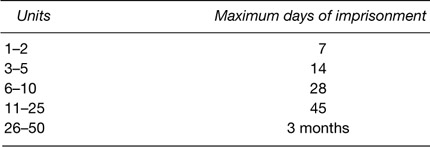

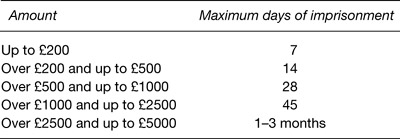

Failure to comply with an abatement notice can result in the defendant being subjected to a fine not exceeding level 5 on the standard scale, together with a further fine of an amount equal to one-tenth of that level for each day the offence continues after the defendant has been convicted. A person who commits an offence on industrial, trade or business premises, however, shall be liable to a fine not exceeding £20,000 (see Table 3.1 for these penalties and others under the EPA). It is a defence to prove that best practicable means were used to prevent, or to counteract the effects of, the nuisance.

Table 3.1 Penalties under the Environmental Protection Act 1990

Section 81 gives the LA power, where an abatement notice has not been complied with, and whether or not they have already taken proceedings, to abate the nuisance themselves and do whatever may be necessary to execute the notice. Any expenses reasonably incurred may be recovered by them from the person whose actions of failure to act have caused the nuisance or be apportioned among several persons accordingly. This section also gives power to an LA, where proceedings for an offence would afford an inadequate remedy in the case of any statutory nuisance, to take proceedings in the High Court for the purpose of securing the abatement, prohibition or restriction of the nuisance, and the proceedings shall be maintainable notwithstanding the LA having suffered no damage from the nuisance.

A person who is aggrieved by the existence of a statutory nuisance need not necessarily pursue the matter through their local authority. Under section 82, a Magistrates’ Court may act on a complaint made by any person on the ground that they are aggrieved by the existence of a statutory nuisance. If the court is satisfied that the alleged nuisance exists, or that, although abated, it is likely to recur on the same premises, the court shall make an order for either or both of the following:

• requiring the defendant to abate the nuisance (an abatement order) within a time specified in the order and to execute any works necessary to achieve this purpose

• prohibiting a recurrence of the nuisance (a prohibition order) and requiring the defendant, within a time specified in the order, to execute any works necessary to prevent the recurrence

and may also impose on the defendant a fine not exceeding level 5 on the standard scale.

If the court is satisfied that the alleged nuisance exists and is such that, in the opinion of the court, it renders the premises unfit for human habitation, an order (as above) may prohibit the use of the premises for human habitation until the premises are, to the satisfaction of the court, rendered fit for this purpose.

See Figure 3.1 for a summary of the procedure in such cases.

Fig 3.1 Statutory nuisance procedure under the Environmental Protection Act 1990

Part IV: Litter and so on

The EPA brought in new procedures regarding the control of litter. Section 87 created the offence of ‘leaving litter’ and section 88 brought in fixed penalty notices for leaving litter. Section 99 also gives LAs the power to deal with abandoned shopping and luggage trolleys.

Part V: Amendment to the Radioactive Substances Act 1960

Part V of the Act makes a number of amendments to the Radioactive Substances Act (RSA) 1960, the principal amendments being:

• provision for the appointment of inspectors

• provision for a scheme of fees and charges payable for registration and authorisation under the RSA

• new powers of enforcement, that is enforcement notices

• withdrawal of the exemption in favour of the UK Atomic Energy Authority from certain requirements of the RSA

• applications of the RSA to the Crown.

Part VI: Genetically modified organisms (GMOs)

The purpose of this Part is to prevent or minimise any damage to the environment that may arise from the escape or release from human control of GMOs. The following definitions are important here.

• the term organism means any acellular, unicellular or multicellular entity (in any form), other than humans or human embryos, and, unless the context otherwise requires, the term also includes any article or substance consisting of biological matter – biological matter meaning anything (other than an entity mentioned above) that consists of or includes:

– tissue or cells (including gametes or propagules) or subcellular entities, of any kind, capable of replication or of transferring genetic material

– genes or other genetic material, in any form, that are so capable

and it is immaterial (in determining if something is or is not an organism or biological matter) whether it is the product of natural or artificial processes of reproduction and, in the case of biological matter, whether it has ever been part of a whole organism

• an organism is genetically modified if any of the genes or other genetic material in the organism:

– have been modified by means of an artificial technique prescribed in regulations by the Secretary of State

– are inherited or otherwise derived, through any number of replications, from genes or other genetic material (from any source) that were so modified

• the techniques that may be prescribed for the above purposes include:

– any technique for the modification of any genes or other genetic material by the recombination, insertion or deletion of, or of any component parts of, that material from its previously occurring state

– any other technique for modifying genes or other genetic material that, in the opinion of the Secretary of State, would produce organisms which should, for the purposes of this Part, be treated as having been genetically modified,

but do not include techniques that involve no more than, or no more than the assistance of, naturally occurring processes of reproduction (including selective breeding techniques or in vitro fertilisation).

Section 108 of the Act requires that no person shall import or acquire, release or market any GMOs unless, before so doing, they:

• have carried out an assessment of the risks of damage to the environment that would be caused as a result of such an act

• in prescribed cases and circumstances, have given notice of this intention and prescribed information to the Secretary of State.

General duties relating to the importation, acquisition, keeping, release or marketing of GMOs are detailed in section 109. Section 110 empowers the Secretary of State to serve a prohibition notice on any person there is reason to believe is: