7 Stretching and Flexibility

How 5 to 10 minutes a day of muscle and connective tissue lengthening perfects your form, and keeps the tightness, injuries, and doctors away.

When I first began working with Olympians in the 1980s, the number of gold medals won by individual athletes was directly proportional to the number of times a week I saw them in my clinic for what we called health maintenance—injury-preventive care that included stretching, massage, icing, and other recovery modalities. Jackie Joyner-Kersee came in the most and ended up with six Olympic medals. Florence Joyner, Flo-Jo, was a close second; she earned four Olympic medals.

The Olympians we work with today watched and learned from their idols. They often do much of their own body maintenance, working out tight muscles and scar tissue with foam rollers, softballs, and home ice baths. It’s the rare elite athlete who doesn’t do any stretching, which is often the most effective strategy of them all for recovery and injury prevention. I have worked with tens of thousands of athletes, from student athletes to pros and Olympic champions, and none have reached their highest genetic potential without a sound flexibility routine.

Unfortunately, even though it’s simple, relaxing, only takes a few minutes, and can be done anytime and anywhere, average runners haven’t gotten the message about stretching yet. Stretching is regarded as superfluous, ignored in the daily rush to the endorphin high. That’s too bad, because inflexibility—i.e., a shortening of the muscles and connective tissue—is a drag on performance, an invitation to injury, and an aging accelerator. This is inevitable unless you do something about it—meaning you must stretch.

Regardless of whether you are athletic or not, you get tight as you age if you don’t stretch. After all, even the most active people are inactive 22 or 23 hours a day, and inactivity has been shown to cause detrimental shrinkage at the cellular level throughout the body’s structural tissues. Our mostly sedentary lifestyle leaves our bodies weak and tight, creating dysfunctional movement patterns that injure soft tissue and joints. The endless sitting in a slumped-forward position rounds your shoulders and trunk, shortening muscles in the front of your body and fixing your posture in a slumped position. In short, movement is life. Inch by inch, year by year, muscles and joints that aren’t moved and stretched lose their range of motion. Before you know it, you start to walk a little more stiffly and bent over, becoming old before your time.

As noted, athletic people are not immune to inflexibility. In fact, running itself can hasten it, tightening the screws in your hamstrings, calves, and back and wrecking your form. Injuries rise as bones and ligaments get pulled out of alignment. Ever see runners and cyclists at their first yoga class? When doing toe touches, most can barely get their hands below their knees. They look like they’re 80. That’s because running, or any workout for that matter, creates damage to the connective tissue structures in and around the muscles. The scar tissue that results will naturally tighten if not stretched. Stretching helps the scar tissue mature into a functional scar, adding strength and preserving the length of your muscles and tendons.

For years, I’ve been obsessed with teaching athletes that the human body requires daily maintenance, just like flossing and brushing your teeth. I’ve given thousands of Saturday morning stretching seminars at my offices and with my partner bike shops and running stores. But to be honest, it is hard to get someone to follow through unless they are already hurt and desperate, or unless I grab their attention with the one surefire statement that every runner wants to hear: Stretching will make you faster.

Yes, you read that right: Stretching will make you faster.

Now I can’t guarantee that stretching will shave 3 minutes off your 10K PR. But I can guarantee that you’ll be injured less if you stretch, so you’ll maintain your training without as much downtime. And I can guarantee that you’ll recover quicker if you stretch, your posture and form will improve, you will run more efficiently, and you won’t look like an 80-year-old when you walk anymore.

The bottom line, from a pure performance point of view, is this:

Flexibility is the first stage of good form, and good form translates to speed and fewer injuries.

For a good example of how inflexibility wrecks good form and slows you down, let’s take body parts that you may not strongly associate with running: pectorals—specifically, tight pecs.

Tight pectoral muscles—most of us get them because we sit all day in a forward-leaning position and tend to favor front-of-body pushing activities over pulling exercises that work the back. This is a big problem for runners. Tight pecs wreak havoc with a vertical arm swing and pull your arm swing toward the center of your body, across your chest. This wrecks the critical vertical arm swing that turns your arms into a forward-motion pendulum. So tight pecs encourage too much side-to-side motion, which puts lateral shearing forces on your hips and knee joints, makes you run in a slightly more crooked line, and generally corrupts your ideal running form, slowing you down. The same story applies as you examine the flexibility of muscles and joints up and down your body.

Flexibility In-Depth

It might be helpful at this point to get a better understanding of flexibility. Technically, flexibility is defined as the range of motion of bones around a joint. Bones must have the freedom of movement to be positioned just right in the sequence of sport motion. This is what we call proper technique. When muscles have inadequate flexibility (i.e., they are tight), the opposing muscle will have to work overtime to put the bones in their ideal position. It’s not hard to see why that can be a problem.

First, you may be so tight that your bones might move slightly out of coordination, in worst cases scraping on each other. That can lead to joint, muscle, and connective tissue injuries.

Second, it takes a lot more energy to get things done when you’re tight. If you’re inflexible during a race, you’ll use up extra energy trying to maintain correct form, which will fatigue you earlier. For performance purposes, regular stretching gives you flexible muscles that allow you to run safely and push it harder with less effort.

Third, because you’re doing less damage during your workout, you’ll also recover quicker.

STRETCHING TARGETS CONNECTIVE TISSUE

Interestingly, stretching doesn’t mean that you are stretching muscle fibers per se. You’re actually stretching the connective tissues.

The red-blood-rich muscle fibers are elastic and will stretch without much resistance, but connective tissue doesn’t. A thin casing of connective tissue surrounds each muscle fiber, wraps them into bundles, and gives them shape. White and glistening, these connective tissue casings are made of collagen, the same stuff that makes up tendons (which attach muscles to bones) and ligaments (which attach bones to bones at the joint).

While the skeletal bones provide the internal frame for the muscles to attach to and protection for the vital organs, it is the collagen connective tissue, or “soft skeleton,” that holds everything together, giving the body its form and dictating how it functions. Where the muscle fibers dissipate toward the end of the muscle, the connective tissue gathers, forming a tendon, which attaches muscle to bone.

Bottom line: Connective tissue is everywhere in the body and vital to health, but most people give it little thought. Physical therapists spend their entire careers dealing with connective tissue and its dysfunction.

This gets us back to why we need to stretch the connective tissue. Like all structures in the body, connective tissue responds to the forces exerted on it. It thickens where it is exposed to stress and thins where it isn’t. Also, it has a natural tendency to shorten over time where it is left unstretched. It is this connective-tissue shortening that limits the range of motion of the joint. A joint with limited range of motion operates with poor mechanics even in the available range of motion, which can lead to damage of the joint surfaces and other structures surrounding the joint.

So, to restore the natural length of the connective tissue, the normal range of motion, and therefore the proper posture and running form, we stretch. The most effective way to restore length is slow, sustained stretching.

Here’s an example of how poor flexibility can ruin good technique: In classic running form, the knee rise in the front of the body should be high enough so that the foot will strike the ground moving backward, gripping and pawing the ground like a bull getting ready to charge a matador. But if you have tight, inflexible butt and hamstring muscles, that knee won’t rise so high, and your foot won’t have enough air time to land correctly. This illustrates how an inability to touch your toes could result in a heel strike.

DIAPHRAGMATIC BREATHING

Central to optimum health and function is how we breathe. Proper breathing normalizes far-reaching functions including circulation, digestion, emotions, mental focus, and even pelvic floor function. Breathing is corrupted by injury, disease, anxiety, and smoking. Instead of deep breaths originating from the diaphragm muscle at the bottom of the chest cavity where the lungs are housed, muscles located higher in the chest and neck create shallow breathing. Instead, we need to breathe deeply using the diaphragm. Athletes and yoga students have learned to use deep breathing to control their focus and improve performance. If you can improve your breathing and harness the power of the breath, you will be a better runner and a healthier person.

Instructions:

• Lie on your back with your knees bent and feet flat on the floor at hip width apart.

• Place your hands on your upper abdomen and breathe deep into your tummy. Feel your hands rise and fall with each slow breath. Note any rise of your rib cage and work to minimize it so that all movement occurs in the abdomen.

Note: Before working out, use this breathing exercise to relax and allow the day’s stress to leave your body.

Rules for Safe and Effective Stretching

To stretch is to de-stress, so savor it. A good stretch is long, slow, and relaxed. Stretching is not something you rush through. It’s a time to relax, prepare your body, and focus on the workout to come. Practice diaphragmatic breathing and stretch before all workouts and at night. Here are the basics.

1. Stretch in a relaxed position.

Stretching is an act of relaxation, so don’t force it. The muscle fibers must be relaxed for the stretch to effectively target the connective tissue elements in and around them. Accordingly, use stretching postures that promote relaxation and protect all the surrounding joints, especially those of the spine. Don’t stretch leg and hip muscles under load—for example, in standing positions that force you to brace yourself, such as bending over and touching your toes or reaching back and grabbing your ankle. Instead, lie on the ground in positions that allow for muscle relaxation and easy breathing. For the upper body, the limb must be relaxed in a cradled or supported posture. Hit each of the major muscle groups while they are relaxed—not stressed.

2. Use the subsiding tension principle.

Muscles should be stretched slowly. Allow the stretch sensation to register in the brain and then modulate it by going deeper into the stretch or letting up based on that sensation. If the tension in the muscle increases while holding a position, then let up a bit. If the tension decreases, then move deeper into the stretch. Deep belly breathing, also known as diaphragmatic breathing, described on page 117, will further relax the muscle. Yoga focuses on deep breathing for good reason—it relaxes the entire body.

3. Use static stretching.

Dynamic movements mesh well with static stretching, but don’t replace it. Although a few recent ill-designed studies found that static stretching reduced immediate power and strength output, decades of research shows that collagen lengthens best under long, sustained stretching and that a static stretch results in the most permanent elongation of the tissue. Stretching before workouts or competition allows athletes to execute the correct biomechanics of their sport. Indeed, my athletes set world records and won gold medals immediately following static stretching.

4. Stretch before all workouts and races.

The most misinformed view of stretching I’ve heard is that it is dangerous to stretch the body when it’s cold. Shy of death, our bodies are never cold! Though collagen tissue stretches better when it’s warmed up, it also stretches just fine at the normal resting body temperature.

To bear this out, just look at dancers; ballerinas don’t go into the dance studio and run around to break a sweat before they stretch. They start the class at the stretch bar—and they aren’t alone. Yogis, martial artists, and gymnasts, all with renowned levels of flexibility, first stretch, then warm up, and then stretch some more. As long as the stretching positions are safe and follow the subsiding tension principle, then stretching before workouts and competition is safe and effective to increase performance and help avoid injury.

Bottom line: There is no excuse for not stretching before a workout. In fact, we say that if you don’t have time to stretch, you don’t have time to work out!

5. Stretch after workouts.

Post-workout, the muscles are “pumped”—i.e., left in a shortened state with the blood vessels in and around the muscle laden with waste products such as lactic acid. Stretching returns the muscles to their normal resting length and promotes recovery by “wringing” the waste products out of the muscle as it pulls the connective tissue taut and staves off the dreaded DOMS (delayed onset muscle soreness). As a result, you recover quicker and begin working out again sooner and stronger. This prevents you from decreasing your flexibility as a result of training.

6. Stretch at night.

The quick 5- to 10-second stretches that you do before and after your workouts are designed to “release” your muscles to their normal resting length and maintain your flexibility. If you want or need to increase your flexibility, you must hold the stretches longer. Doing them later at night when your muscles and tendons are looser from the day’s activity will create a more permanent elongation of the connective tissue and relax you for a better night’s rest.

In summary, stretching is a crucial part of your workout plan. Done before and after you work out, and safe when done “cold,” stretching prevents injury, loosens up problem tight areas before injuries occur, gives you the flexibility to run with proper biomechanics and technique, and serves as a mental and physical warm-up routine before exercise. Given that it feels good, is free, fixes your posture, and makes you look better in a business suit or running shoes, it’s not smart to go without it.

The Stretches

The stretches below are not just for injured runners. They target all the crucial muscles to improve range of motion and performance as well as prevent injury. The 20 movements here are sequentially ordered in a specific routine, much like yoga, that progresses from lying on your back to lying on your side to all fours to kneeling and finally to standing. This gradually prepares your body for workouts and, afterward, for the post-workout recovery.

Do the stretches on both sides of your body to maintain symmetry. This can help you identify tight muscles on either side that require more attention. So, if you find a tighter side, work on it with a longer hold and additional reps compared to the other side.

When using stretches as a warm-up or cooldown, hold them for 5–10 seconds and do 2 repetitions of each. If the primary goal is to become more flexible, hold the stretches longer, from 10 to 30 seconds, and perform 3 reps of each.

1. Press-ups

An important exercise to increase and maintain lumbar extension and range of motion; press-ups are used to prevent and treat lumbar disc bulges. You may feel tight or sore in the low-back as you do this one, so only go to the point of discomfort and stop doing it if any pain radiates into your buttocks or lower extremities.

Instructions:

• Point your toes toward each other to keep your gluteal muscles relaxed during this exercise.

• Lie face-down with your palms flat on the mat near your shoulders, elbows pointed outward. Use only your arms to push your chest up. Extend as far as possible while keeping your pelvis on the mat.

• Don’t hold at the top for more than 1 second before returning to the floor. Repeat up and down 10 times.

• Don’t push past pain.

• Keep your head in a neutral position.

2. Pelvic tilt

Not a stretch, the pelvic tilt is a maneuver we do to be sure that your lower back is flat and safe on the ground before performing various exercises.

Instructions:

• Lie on your back with your knees bent and your feet flat on the mat hip width apart.

• Tighten your abdominal muscles and pinch your glutes together as you push your lower back flat into the mat. As you hold these muscles contracted, continue to breathe.

• Count to 5. Repeat 3 times.

3. Pelvic rotation

This stretch, plus the pretzel that follows, addresses the buttock muscles and is critical to avoiding injury. More than 50 percent of the running injuries we see are related to buttock and hip dysfunction.

Instructions:

• Lie on your back with your knees bent and your feet flat on the mat hip width apart, arms extended and even with shoulders.

• Cross your right leg over your left, knee over knee.

• Drop both legs to the right side, and slide them up toward your head as they maintain contact with the ground.

• Keep both shoulders on the mat and turn your head to the opposite direction. Breathe and hold for a count of 5. As you return your legs back to the start position, resume a pelvic tilt. Perform 2 repetitions on each side.

Note: Keep the foot of the bottom leg in contact with the mat throughout the stretch, and don’t scoot your hips to the side before dropping your knees over.

4. Pretzel

The pretzel specifically addresses tightness in the deep rotators of the hip, an area where common running injuries originate. It is the most preventive stretch for piriformis syndrome, a neuromuscular disorder that causes pain down the sciatic nerve in your leg when the piriformis muscle compresses it.

Instructions:

• Lie on your back with your knees bent and your feet flat on the mat hip width apart.

• Do a pelvic tilt and cross your right leg over your left, knee over knee.

• Place your right and left hands on your right knee.

• Pull your right knee toward your left shoulder. Breathe and hold for 5 seconds.

• Repeat with your left leg over your right leg. Do 2 reps on each side.

Note: Keep your shoulders pulled back during this stretch. As long as you are pulling your top knee toward the opposite shoulder, it’s okay to rotate the leg by pulling more on the knee.

5. Figure 4

This is an important stretch to maintain hip range of motion and prevent hip joint deterioration. It’s also important because it stretches the rotator muscles deep in the buttocks. Note: If you have an unequal range of motion in one hip or the other, spend extra time stretching the tight hip.

Instructions:

• Lie on your back with your knees bent and your feet flat on the mat hip width apart.

• Do a pelvic tilt and place your right ankle on your left knee.

• Use your right hand to push your right knee away. Breathe and hold for 5 seconds.

• Switch legs and repeat. Keep your pelvis symmetrical throughout the stretch. Do 2 reps on each side.

Note: To increase the stretch, lift your left leg off the floor and hold it behind the knee as you push down with your right hand. Also try the stretch as above, but instead of pushing the right knee away, pull both legs toward your trunk to increase the stretch.

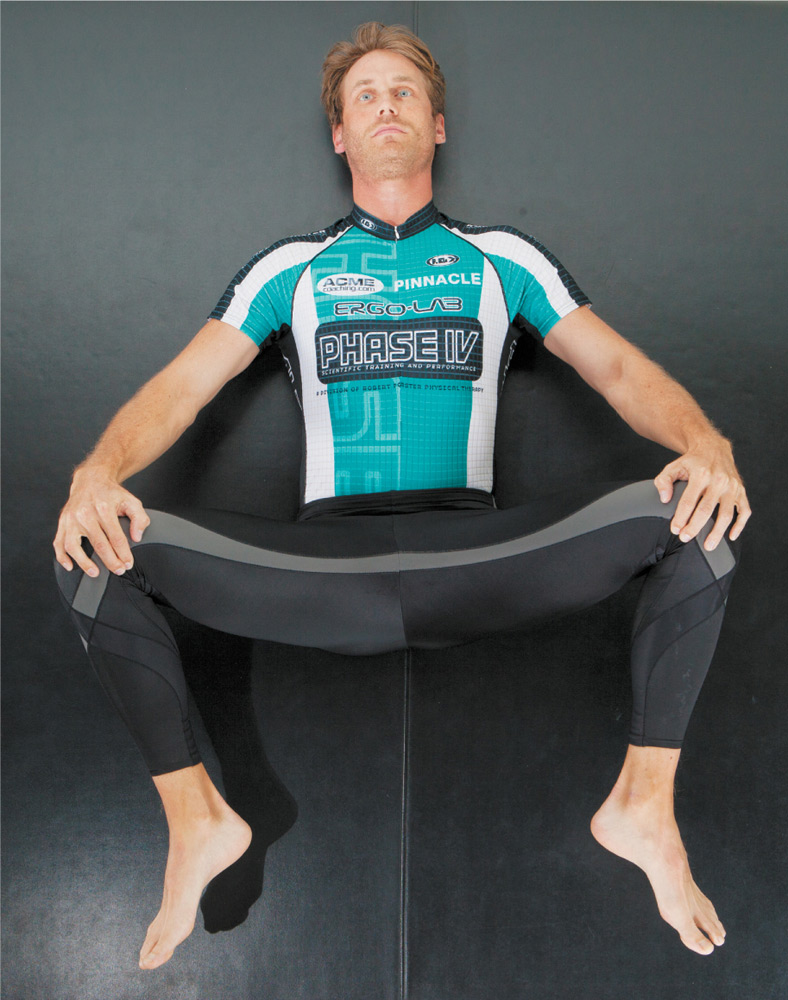

6. Supine Adductor

Place your hands on the insides of your knees and apply light pressure, feeling the stretch at the inner thigh as your legs remain airborne.

Instructions:

• Lie on your back and perform a pelvic tilt, raising your thighs so they are perpendicular to your body at 90 degrees. Bend your knees, feet up in the air.

• Place your hands on the inside of your knees and let both knees and feet drop outward. Apply light pressure with your hands. You should feel the stretch at your inner thigh. Hold for a count of 10. Repeat twice.

Note: Keep your knees and hips bent at right angles.

7. Side-Lying Quad Stretch

Doing this stretch regularly is the single most important thing you can do to avoid knee injuries as you continue running. The quadriceps tighten over time and create excessive wear on the kneecap as it tracks between the condyles (the two round prominences at the bottom of the thigh bone) of the femur. If left unstretched, runners are susceptible to patella tendonitis, or “runner’s knee,” and early arthritic changes in the knee. This is the one stretch that we will allow runners to work with, not through, some discomfort, because the stretch serves the greater good of improving the joint mechanics. This means that you need to continue doing this stretch when the discomfort is merely mild, doesn’t worsen with each repetition, and you don’t experience more pain in daily activities such as climbing stairs or squatting after doing this stretch.

Instructions:

• Lie on your side with your head on your arm and your hips perpendicular to the floor.

• Bend your top knee and grab your shoelaces and toes behind you with the same-side hand. Pull your heel to your buttocks. Feel the stretch at the front of your thighs. Hold for a count of 10. Do 2 reps on each side.

Note: During the stretch, keep your abdominals firm to support your back. Also, keep your top leg level with your heel behind you and don’t hyperextend your back. Keep your shoulders and hips stacked. You should not be able to see your stretched knee if you look down your body.

8. Catback

This is an important exercise to stretch the muscles around your spine from your neck all the way down to your sacrum (the fused vertebrae at the bottom of the spine). If at any time you feel unbalanced, move your knees farther apart.

Instructions:

• Start on your hands and knees, with your hands below your shoulders and your knees below your hips.

• Arch up the middle of your back into a mild stretch and relax your head and neck. Feel the stretch in your mid-back. Make sure your arms and thighs are vertical. Hold for a count of 10.

• Return to the original position, and repeat.

9. Prayer Position

This movement stretches the hard-to-get-to muscles in your lower back that are susceptible to tightening in runners (especially those with a leg-length discrepancy).

Instructions:

• From the catback position, simply rock yourself back toward your calf muscles, bend your elbows, and aim your chin in-between your knees.

• Walk both hands over to the left above your head, anchor your right hand to the mat with your left hand, and pull back through your left buttock. Feel the stretch anywhere from your right lat into your lower back. Over time, as you stretch out your lat, the stretch will focus on the lower-back muscle.

• Hold for a count of 10 and repeat on the other side.

10. Kneeling Hip Flexor Stretch

The hip flexors will shorten with time with continued running, often causing lower-back pain and injury. Keeping them stretched out prevents groin injuries and spinal problems.

Instructions:

• Kneel on your right knee with your left foot at arm’s distance in front, knees spread apart.

• Keep your trunk upright and hips and shoulders square, and lunge forward until your left knee is over your left foot. Feel the stretch at the front of your right hip.

• Hold for a count of 10 and repeat on the other side.

Note: If your front knee passes your foot, then move your front foot farther forward; your front knee should never go past the toes. Keep your trunk upright during this stretch.

11. Standing Hamstring Stretch

It is critical to promote good flexibility in the hamstring muscles to maintain good running form and prevent injury to your knees, buttocks, and lower back. Notice that the model in the photo does not bend over and touch his toes because there is no need to stress the lower back.

Instructions:

• Stand with your feet pointing straight ahead.

• Put the heel of one leg up no higher than a surface.

• Think about pulling your buttocks back as you hinge at the hips. Keep your back flat as you angle your trunk forward at your hips. Keep your elevated foot relaxed. Stop when you feel the first sign of stretch in the hamstrings. Hold for a count of 10. Repeat on the other side. Do 2 reps on each side.

12. Standing Adductor Stretch

This stretch addresses the inner thigh muscle (adductors), a strong and powerful muscle group that is active in running. It both stabilizes your pelvis and moves your leg forward and backward during the running gait.

Instructions:

• From the hamstring stretch position, pivot your supporting foot, leg, and trunk outward 90 degrees and keep your toes pointing up as shown. In this posture, you should feel the stretch in the inner thingh.

• To get more of a stretch in your inner thigh, bend your supporting leg slightly. You can maximize a stretch in your inner thigh by bending your torso sideways toward the raised leg. Always maintain a flat plane from hips to head. Hold for a count of 10. Do 2 reps on each side.

13. Standing Calf Stretch

Stretching the calf muscles is essential to maintaining the full range of motion of the ankle to ensure proper running mechanics and maintain the health of the Achilles tendon. Stretch the two heads of the gastrocnemius muscle by keeping the rear leg straight while leaning forward. The next exercise works the soleus, the deeper muscle.

Instructions:

• Stand in front of a wall with a staggered stance. Keep both feet pointing forward and your heels on the ground.

• Place your hands on the wall and hold your back heel down as you bend your elbows to bring your chest toward the wall. The stretch should be at your upper calf.

• Hold for a count of 10. Do 2 reps on each side.

14. Standing Calf Stretch with Bent Leg

People often forget the soleus—and pay the price with shin splints and other deep calf injuries.

Instructions:

• In the standing calf position (see page 131), bring your back leg forward 3 to 4 inches (7.5 to 10 cm) and bend your back knee. The stretch should be in your lower calf and Achilles.

• Hold for a count of 10. Do 2 reps on each side.

Note: Oftentimes, this stretch will be more effective in shoes than when barefoot. Also, if you feel “jamming” in the front of the ankle, stop at the point where you feel it. Over time, that tension will subside and you should only feel the stretch in your lower calf.

15. Chin Tuck

This simple exercise will not only improve your posture, but it may save your neck from the damage we all suffer with long hours of sitting. Feel the stretch anywhere from the base of your skull down into your upper back.

Instructions:

• Gently pull your head back, keeping it level. Your head should not tilt up or down. Keep your back straight and chest high.

• Make a double chin by pulling your chin in toward your neck. Do not bend your neck forward or drop your chin.

• Elongate or flatten your neck in back. Keep your head level.

• Hold for a count of 5. Perform 2 repetitions.

16. Cross Chest

This is one of several stretches that target the back of the shoulder, a problem area that is the source of rotator cuff injuries and other shoulder problems.

Instructions:

• Place your left arm in front of your body at chest height.

• With your left hand, pull your right arm across your body, holding the elbow. Keep your shoulder down and relaxed. Be cautious to not pull your arm down too hard. Keep your shoulders down and square.

• Hold for a count of 5 and repeat on the other side.

Note: If you feel a “pinch” in your shoulder, try to pull your arm first away from the body and then across.

17. Standing Upper Trap

This stretch relieves much of the tension we all hold in our upper back and neck. It benefits running by allowing for the proper path of a vertical arm swing on the side of the body.

Instructions:

• Pull your left arm gently by the wrist with your right hand downward and to the right behind your back toward the right buttock.

• Bring your chin down to your chest and then rotate to the right to look toward your right armpit, keeping your head down. Feel the stretch from the left side of your neck into your upper back. Hold for a count of 5.

• To return, bring your head back to the middle position and then up.

• Repeat on the opposite side.

Note: Be cautious not to pull your arm down too hard during this stretch. Keep shoulders square.

18. Penguin

This stretch was invented in our clinic to address the tightness we all suffer in the posterior muscles of the rotator cuff. It will improve the efficiency of your arm swing.

Instructions:

• Standing with head up and back and a “proud” chest, place the back of your fists at the pelvis (the top of your buttocks), with palms facing backward.

• Pull your elbows forward. Do not curl your shoulders forward. Keep your shoulders back. Feel a diffuse, general stretch in your shoulders. Hold for a count of 10.

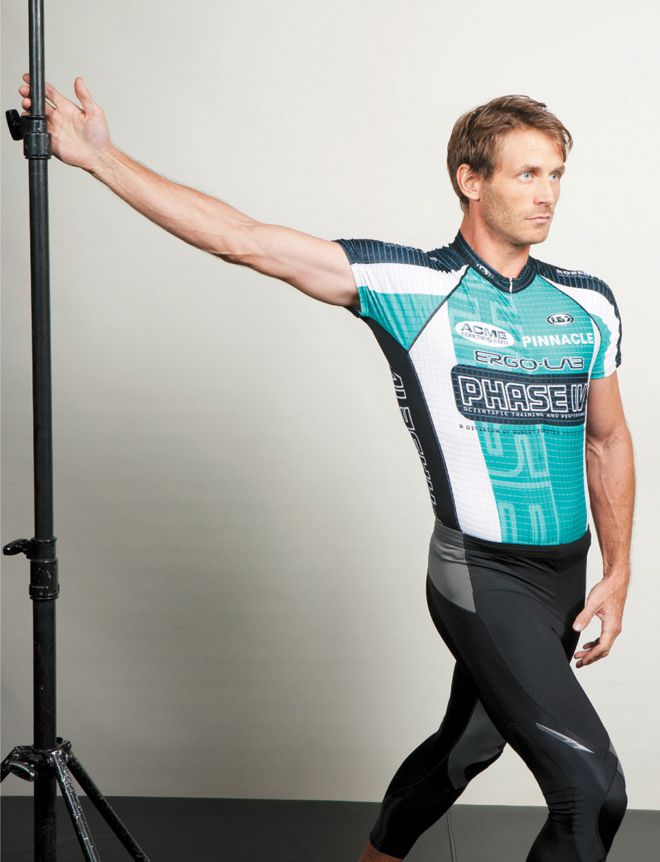

19. Pec Stretch

Most of us have overdeveloped, tight pecs that corrupt our posture, stress our neck, and deviate our arm swing in running. Tightness in the pecs prevents a good backswing and creates an inefficient cross-chest arm swing. This stretch restores that flexibility.

Instructions:

• Line your body up with a wall or door frame. Make a loose fist and place your hand thumb side at wall level with the top of your head.

• Take a step forward with the same-side leg to get a stretch at the front of your shoulder and chest. Keep your torso upright and your eyes looking forward. Keep your hips and shoulders perpendicular to the wall.

• Hold for a count of 10 and repeat on the other side.

20. Overhead Triceps Stretch

The triceps muscle group crosses the shoulder and the elbow joint. Running will create tightness in this muscle group, which will corrupt your running mechanics and posture.

Instructions:

• Raise your right arm up overhead, bending your elbow so your hand is behind your neck.

• With your left arm, pull your right elbow back behind your head.

• Feel the stretch in the back of your left arm and along the side of your shoulder blade.

• Hold for a count of 10 and repeat for your left arm as well.

Note: Keep your head level and not forward. To get more stretch, side-bend your torso.