CHAPTER 3

coaching with compassion

inspiring sustained, desired change

People tend to change their behavior when they want to change and in the ways they want to change. Without an internal desire to change what or how they behave, any noticeable differences are often short-lived. We’ve seen this time and again in our observations of managers who coach employees to alter their behavior in order to conform to organizational expectations, or with athletic coaches coaching players to show more commitment to the game by lifting more weights and studying films. We’ve seen it in how physicians coach their patients around lifestyle changes they should make in the interest of their health and with career coaches who direct their clients to specific opportunities based solely on their skill sets or employment history.

All of those examples describe a common view of coaching—as an activity where, based on your experience, expertise, or authority, you advise individuals on what they should do and how they should do it. While there may be a time and place for it, this type of coaching for compliance is unlikely to lead to sustained behavioral change. Just look at the estimated 60–70 percent failure rate of organizational change initiatives, which ultimately rely on individual behavior change.1 Or look at the nearly 50 percent of chronically ill patients who fail to adhere to their prescribed treatment plans.2 Being told that we have to or need to change is simply not an effective means of helping us to sustainably alter our behavior.

In this chapter, we will explore in detail the differences between coaching for compliance and coaching with compassion. We will also introduce a five-step process—with coaching with compassion at its core—that’s been proved key for creating sustained, desired change. Let’s begin with a story that illustrates how one of this book’s authors experienced firsthand the power of being coached with compassion versus compliance.

unlocking the power of passion

After nearly fifteen years in sales and marketing management, Melvin decided to return to school full time to pursue a PhD in organizational behavior and human resource management. He was excited at the prospect of teaching at the university level as well as engaging in corporate training and consulting. He quickly learned, however, that the top PhD programs sought to admit students interested in research—not teaching and consulting. In his application, therefore, he took the advice of a professor he knew and presented himself as someone clearly interested in research, but who was also interested in the practical application of that research through teaching and consulting. His strategy was successful, and he was admitted into the doctoral program at the University of Pittsburgh, where he performed well and honed his research skills, positioning himself as a promising scholar.

Upon attaining his doctorate, Melvin landed a tenure-track position at Case Western Reserve University, solidifying his transition into an academic career. During his first year on the faculty, he did what was necessary to establish and pursue his research agenda. By his second year, he’d also been pulled into teaching a couple of programs for executives in addition to his degree-program teaching responsibilities. Before long, he realized that he was spending more and more of his time and attention on teaching, which he enjoyed immensely. He loved inspiring people to apply and use knowledge from his own and his colleagues’ research. The enthusiasm his students and program executives felt was electric and contagious. But his research agenda had begun to stall.

During this time, Melvin received informal coaching advice from his department chair and others that he should focus much more on moving his research forward since he’d need to show progress on that front in his upcoming third-year review. He knew this was important and that it was what he ought to be doing, so he began to shift his behavior. He progressed on key research projects and put together a respectable packet for his third-year review, articulating his research agenda and demonstrating his progress. He passed his third-year review but was cautioned about the amount of time he spent on nonresearch activity. Teaching, advising doctoral students, and working with executive education should all be secondary if he hoped to gain tenure.

While he appreciated that advice, Melvin nevertheless found himself continually pulled toward teaching in the degree programs and executive education. Not only did he enjoy helping people learn, but he’d also discovered he was really good at it. He found himself straddling the fence between what he knew he ought to be doing and what his heart told him he really enjoyed. Yet he saw no way around it.

In his fourth year, Melvin had a chance to work formally with a coach as part of a grant-funded program in his department.3 He anticipated that, as he’d experienced with past coaching, his new coach would focus on what he needed to do to achieve promotion and tenure. But he soon realized that she wasn’t pursuing any externally defined agenda whatsoever. She was simply there to help him articulate what he wanted to do and who he wanted to be in the future—as he envisioned it—and to help him figure out how to move in that direction.

It didn’t take the coach long to identify the tension Melvin had been struggling with for quite some time. On one hand, he expressed a desire to focus on his research for the next few years and earn tenure. On the other hand, however, he wanted to continue, if not expand, the work he’d been doing in executive education. He also expressed a desire to take advantage of the variety of paid speaking opportunities he was now receiving on a fairly regular basis. He hoped it would be possible to “have it all.” But he soon understood that to have both, he’d have to postpone teaching and paid speaking opportunities until after tenure, which was still more than five years away, given the school’s nine-year tenure process. While he told himself that both the research and teaching were important, he continued to feel frustrated that he wasn’t fully applying himself to either endeavor.

While it would have been easy to coach Melvin in the direction that his department and the school encouraged, instead his coach challenged him to identify which way his heart was telling him to go. She asked him to engage in a hypothetical exercise.

“What if you had to make a forced choice,” she asked, “and in choosing one option, you’d have to forgo the other completely? Under that scenario, which would you choose?” Watching him struggle with the decision, she said, “What if you just choose one and hypothetically try it on—like you would a coat—for a while to see how it feels? If you don’t like it, take it off and try on the other one for a while. Then we’ll get back together and talk about it.”

Melvin “tried on” the research and tenure path first. He imagined what it would be like if he did no executive education or outside speaking engagements at all. He began to pour all of his mental and physical energy into his research. He stayed in that space for a short while, but he soon realized he didn’t like how it felt. The thought of remaining in that space for a long period of time was actually uncomfortable. He felt he’d be missing out on something he really wanted to be a part of.

At that point, as his coach had suggested, Melvin switched his mindset toward the executive education and speaking engagement option. Almost immediately, he felt a difference. While the thought of not doing as much research wasn’t something he viewed as ideal, he was surprised at how much better this option felt than the previous one. He felt a real excitement about the various activities and opportunities he’d be pursuing with this option.

There was no question what his heart was telling him. “This is it!” he thought.

When he next saw his coach, Melvin shared his new insight, and the remainder of his coaching sessions focused on the steps he’d make to move toward his true passion and ideal vision for his future. Soon he grew comfortable with the fact that he was choosing to primarily teach and speak as opportunities presented themselves. If doing so meant he’d have less time for research—and therefore would be less likely to get tenure—he realized that he could live with that. The research felt like more of a push, something he felt he ought to be pursuing, rather than something he wanted deep down inside. His coach had helped him see that.

For the next several months, Melvin was happier than he’d been in quite some time. The tension he’d wrestled with for so long had been lifted. He was pursuing what he wanted to do in his heart and was comfortable with wherever that was leading him. Then, unexpectedly, he was approached about a new position being created at the school—Faculty Director of Executive Education. If he accepted the job, he’d get to play a significant role in growing the school’s executive education business. The only catch was that it was a non–tenure track position; to take the job, he’d have to leave the tenure track.

Had it not been for the coaching he’d received and making the discoveries he did about his ideal future, Melvin likely wouldn’t have even considered the position. As it turned out, however, he ultimately accepted the job, which he has now enjoyed for more than twelve years. He’ll tell anyone who will listen that it was one of the best career decisions he ever made, and that he couldn’t have written a better job description for himself. Not only has it allowed him to accept speaking and training engagements throughout the world, but he has also continued to teach in the school’s degree programs he enjoys the most while remaining involved with the research and writing projects that truly interest him.

Had Melvin’s coach focused on pushing him toward “compliance” rather than compassionately helping him to identify and pursue his vision for his future, imagine how different the outcome might have been. Fortunately, Melvin’s coach essentially guided him through five phases, or discoveries, of what we call intentional change.

a model for intentional change

A proven method of coaching with compassion in a way that leads to sustained desired change is to guide an individual through Boyatzis’s model of intentional change (see figure 3-1). Intentional Change Theory (ICT) is based on the understanding that significant behavioral change does not take place in a linear fashion. It does not begin with a starting point and then progress smoothly until the desired change has been completed. Instead, behavioral change tends to occur in discontinuous bursts or spurts, which Boyatzis describes as discoveries. Five such discoveries must occur for an individual to make a sustained desired change in behavior.4

FIGURE 3-1

Boyatzis’s Intentional Change Theory in fractals or multiple levels

Source: Adapted from R. E. Boyatzis, “Leadership Development from a Complexity Perspective,” Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research 60, no. 4 (2008), 298–313; R. E. Boyatzis and K. V. Cavanagh, “Leading Change: Developing Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Competencies in Managers during an MBA Program,” in Emotional Intelligence in Education: Integrating Research into Practice, ed. K. V. Keefer, J. D. A. Parker, and D. H. Saklofske (New York: Springer, 2018), 403–426; R. E. Boyatzis, “Coaching through Intentional Change Theory,” in Professional Coaching: Principles and Practice, ed. Susan English, Janice Sabatine, and Phillip Brownell (New York: Springer, 2018), 221–230.

discovery 1: the ideal self

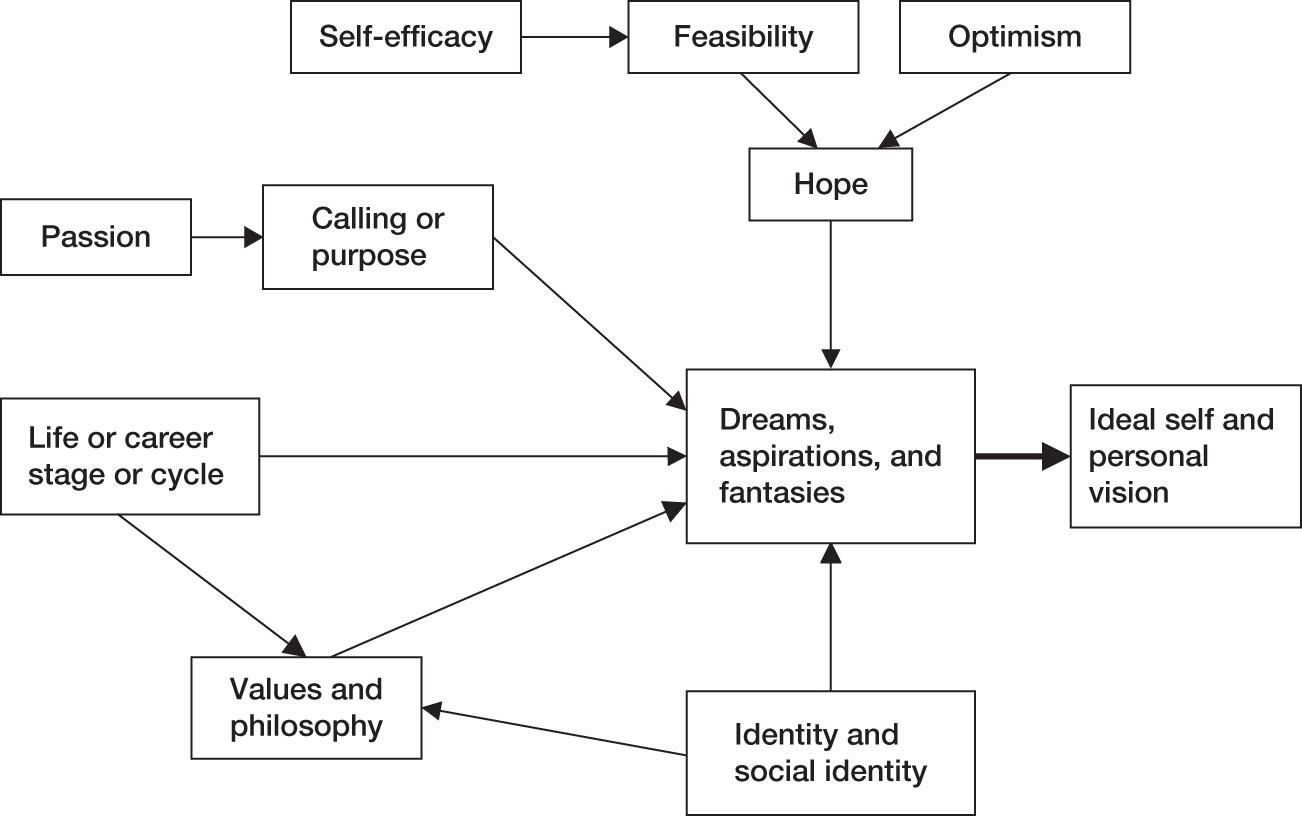

Helping people with the first of these discoveries begins with an exploration and articulation of their ideal self, answering such questions as “Who do I really want to be?” and “What do I really want to do with my life?”5 Note that this is not just about career planning. It is much more holistic. It is about helping people envision an ideal future in all aspects of their life, taking into consideration but not being limited by their current life and career stage. The helper or coach encourages them to draw on their own sense of self-efficacy and tap into feelings of hope and optimism about what might be possible. They will also be encouraged to reflect on their core values, core identity, and what they see as their calling or purpose in life. As a result, they ultimately will be able to articulate a personal vision for their future—and/or a shared vision they might have that includes their family, work group, or a larger social cause (more on this below and in chapter 6). (See figure 3-2 for a model of the ideal self.)

FIGURE 3-2

Components of the ideal self

Source: Adapted from R. E. Boyatzis and K. Akrivou, “The Ideal Self as the Driver of Intentional Change,” Journal of Management Development 25, no. 7 (2006): 624–642.

When coaching individuals toward discovering their ideal self, be sure they are tapping into who they really want to be and what they really want to do. Too often, people think they are articulating an ideal self when, in fact, they are describing what could be called an “ought” self—who they think they ought to be, or what others think they ought to be doing with their lives. We saw this in Melvin’s story: when he was chasing what he thought he ought to do (more research in pursuit of tenure) rather than what he ideally wished for (more teaching and speaking engagements), the energy and enthusiasm needed for a sustained behavior change was just not there.

Helping people genuinely discover their ideal self involves more than guiding them through a series of cognitive or mental exercises. Instead, it is about facilitating a process (often through exercises or reflections, which we will describe here and throughout this book) that leads to an emotional experience where they feel as if a flame has been ignited inside of them around their passion. That’s how you and they will know that they have truly tapped into who they are at their best and what they care most deeply about.

An effective way to help people fully explore their ideal self is to have them craft a personal vision statement. We know that when organizations create clear and compelling vision statements that are shared by members of the organization, the results can be positive and powerful. They can help motivate, engage, inspire, and provide a sense of purpose and direction. We believe that a personal vision statement for one’s life can be just as meaningful for an individual. The adage, “The odds of hitting your target go up dramatically when you aim at it” sounds obvious. But it’s also true: Isn’t going through life without a personal vision statement just like shooting at a target without aiming at it?

In some of our programs and courses we show the video Celebrate What’s Right with the World, narrated by photojournalist and corporate trainer DeWitt Jones.6 In it, Jones stresses the importance of having a personal vision. He encourages viewers to boil that vision down to a six-word statement that they can memorize and that will inspire them each day. As a coach, that’s one of the most powerful things you can do to help people make meaningful, sustained change: help them find the passion and enthusiasm associated with identifying their ideal self and articulating a personal vision statement.

discovery 2: the real self

Coaching people on the second discovery of the intentional change process involves helping them uncover an accurate view of their real self. This is not just about assessing strengths and weaknesses. Instead, it is about helping them identify holistically and authentically who they are relative to who they want to be as expressed in their personal vision.

An important role for the coach during this discovery is to help individuals identify the areas of their lives where their ideal self and real self are already aligned. Those areas are their strengths, which can be leveraged later in the change process. Next, the coach should help individuals identify any areas where their real self is not currently aligned with their ideal self. These represent gaps that can ideally be closed through targeted behavioral change efforts.

A coach should also help individuals recognize that their real self comprises more than just how they see themselves—they also need to consider how others see them. Some might argue that how others see them is rooted in perception and doesn’t necessarily reflect who they really are. But the truth of the matter is that others’ collective perceptions of us essentially represent how we show up in the world, which is a key aspect of who we are. Thus, to help the people they are coaching enhance their self-awareness and develop a more comprehensive view of their real self, the coach should suggest they periodically seek feedback from others. In other words, regardless of their intentions, how do others actually perceive them?

When we hear about self-awareness, especially relative to leadership, the focus is often on people’s internal self-awareness—their own views of their strengths and weaknesses, as well as their values and aspirations. While important, this focus neglects the other critical aspect of self-awareness: how they are seen by others. Without accurately reading how they are perceived by others, their view of their real self is incomplete.

One way to enhance self-awareness is to receive multi-rater feedback (also known as 360-degree feedback). This process enables individuals to assess themselves on a variety of behaviors, while also being assessed by others from a number of relationships and/or contexts. The traditional view is that comparing one’s self-assessment to the assessment of others is a way to gauge one’s degree of self-awareness. Our friend and colleague Scott Taylor of Babson College, who has done considerable work in the area of leader self-awareness, suggests that a better indicator of self-awareness is actually people’s prediction of how others see them measured against how others actually see them.7 A good coach will therefore help individuals being coached gain a greater degree of self-awareness, and hence a better sense of their real self, by helping them develop their capacity to “tune in” and effectively read how they are perceived by others. That way, they can regularly assess how much their intentions reflect the actual impact they have on others.

Not everyone has the resources or opportunity to participate in a multi-rater feedback assessment process. But there are other ways to accomplish the same goal. First, a coach or other helper can ask individuals to honestly assess the things that they tend to do well (or be good at) and the things they tend to not do so well (or not be so good at). Research suggests that this self-assessment may be biased—but it’s still an important part of the process. Next, following the advice of Scott Taylor, the coach should have the individuals predict how others would assess them on key behaviors of interest. And finally, they can actually seek informal feedback from others to see to what extent their predictions of how they’re perceived by others match others’ actual perceptions.

Having individuals create a “personal balance sheet” (PBS) is another way to help them capture a snapshot of their real self at any point in time, whether or not they have participated in a formal feedback process. With it, they can categorize their short-term and long-term strengths and weaknesses (or development opportunities). They can then weigh those against their ideal self and personal vision statement to determine where they align and where there are gaps. Once they recognize and acknowledge the strengths and gaps between their ideal self and real self, they are ready to move forward with the change process.8

The feedback that Melvin received early on as a faculty member suggested he had good teaching and facilitation skills and was an engaging speaker. He recognized those as strengths he could further develop and leverage to become an effective educator and requested speaker. Melvin also received feedback that his research productivity was on the low side. At the time, he had a relatively limited number of active research projects, which were advancing at a moderate pace at best. Had he viewed this feedback in an absolute sense and taken a traditional development path as a result, he would have likely focused his greatest attention on closing the gap represented by a key identified development opportunity—in this case, his research productivity. After working with his coach to clarify his personal vision, however, it became clear that he should direct his energy to working with his identified strengths, which directly supported the most important professional aspects of his vision. That didn’t mean ignoring the feedback about his research productivity. He just put it in perspective, deciding to first tap into the positive emotional energy he felt around using his strengths in pursuit of his vision.

This is an important consideration when using a PBS. Often, individuals will immediately turn their attention to the weaknesses and begin thinking of ways to address them. But a compassionate coach can help them see how to make their change efforts more successful—by first acknowledging and leveraging their strengths. Only then should they attempt to address any identified weaknesses, focusing primarily on those that help them make the most progress toward their personal vision.

discovery 3: the learning agenda

The third step in the intentional change process is crafting a learning agenda. The coach or other helper first asks individuals to revisit the strengths identified in the previous discovery and then think about possible ways those strengths might be utilized to close any relevant gaps. The key here is for people to think about what they’re most excited to try in the way of behavior changes to help them grow closer to their ideal self. This is different than a performance improvement plan where they focus on addressing all their shortcomings. That begins to feel like work and can actually inhibit the change process.

Rather, the coach should help individuals recognize that if they continue to do what they’ve always done, they’ll continue to be who they’ve always been. To change, they’ll have to do some things differently. This was the uncomfortable tension Melvin was experiencing—straddling the fence between making teaching or research his first priority. Although he felt that tension, he continued to engage in the same behaviors of not fully committing himself to either path. It was as if he expected that tension to magically disappear over time.

Getting a feel for which path is most exciting is another way to check that you are on the way toward your purpose and vision rather than someone else’s notion of what you should do. For example, whenever Melvin was offered the opportunity to design a new learning experience such as a workshop or course, he jumped at it. If it was a choice between designing a new learning experience or working on a research paper, he always chose the learning experience first. This had the most magnetic pull for him. It was a positive attractor that had a stronger pull than the research.

Doing something differently is also the essence of the first half of the fourth discovery (which we’ll describe momentarily). It involves experimenting with and then practicing new behaviors. While articulated as a distinct discovery, these experimentation and practice efforts are actually planned for during the creation of the learning agenda. In essence, the third discovery entails planning what one is going to do, whereas the fourth discovery involves putting the plan into action.

discovery 4: experimenting with and practicing new behaviors

This is the fourth discovery in the intentional change process, where the coach encourages the individual to continually try new behaviors and actions, even if they don’t always lead to the intended outcome. Experimentation efforts sometimes fail, and that’s okay. That’s the nature of experimentation. If something doesn’t work as anticipated, the coach should encourage the person to either try it again or try something else.

Melvin’s coach asked him to focus on one of his two competing professional pathways (teaching/speaking versus research). She challenged him to choose just one, with the understanding that he was doing so at the complete expense of the other. As discussed earlier, Melvin completed the experiment and realized that although he didn’t like eliminating research and writing completely, he got an empty feeling when he considered making that the focus of his work. He realized that he didn’t get that same empty feeling when he placed an exclusive focus on teaching and speaking. He actually felt energized—and this proved to be a breakthrough toward Melvin’s sustained desired change.

To trigger the desired “a-ha” of this fourth discovery, the key is to continue experimenting until people find something that works for them. Then the coach can help them shift their experimentation efforts into actual practice, which is the second half of the fourth discovery. At this point, it’s critically important to practice and then practice some more. But many people stop short of that, practicing only to the point where they feel comfortable with the new behavior. That’s fine for temporary behavior change, but it doesn’t work consistently when we are rushed, overwhelmed, angry, sleep-deprived, or under stress and aren’t thinking clearly. That’s when we’re likely to fall back on old behaviors. But if we can keep practicing until we move beyond comfort to the point of mastery, we can change our behavior in truly sustainable ways.

For Melvin, this meant practicing saying “no” to requests to get involved with time-consuming, long-term research projects outside of his primary research area. Previously, he almost always said “yes” to these opportunities because he felt they would help build his research pipeline. Once he developed clarity around his newly articulated focus, however, he had to develop a new habit—being more disciplined with his time and how he responded to such requests, accepting only what interested him the most.

Several researchers and authors have offered views on how long one must practice new behaviors to reach the point of mastery. In his 1960 book Psycho-Cybernetics, Maxwell Maltz suggested that it takes at least twenty-one days to form a new habit.9 Stephen Covey and many others subsequently latched on to that same notion, that habits could be formed in twenty-one days of repeated practice.10 Malcolm Gladwell, in his 2008 best-seller Outliers, suggested that mastery requires about ten thousand hours of practice.11 Phillippa Lally and her colleagues at University College London studied the topic and found that there was actually considerable variation in how long it took individuals to form a habit, with their study results showing a range of 18 to 254 days.12

Regardless of the specific amount of time that’s necessary, coaches and other helpers should encourage individuals to practice behaviors they hope to solidify. Individuals being coached should practice the behavior until they don’t have to think about it to do it well, when it becomes their new default.

discovery 5: resonant relationships and social identity groups

In coaching to the fifth and final discovery of the intentional change process, a helper or coach helps people recognize that they’ll need continued assistance from a network of trusting, supportive relationships with others. Making significant behavioral change can be difficult, and it’s even harder in isolation. Change efforts will be more successful when embedded within what we describe as resonant relationships, based on genuine, authentic connection that has an overall positive emotional tone. While the connection with the coach or primary helper should be one of those relationships, individuals should also have others they can turn to for support, encouragement, and sometimes accountability. That’s what they’ll need as they work through each of the discoveries of the intentional change process. We often refer to such a network as a “personal board of directors.” Through trusting, supportive relationships along with the formation of social identity groups (more on this in chapter 8), a person benefits from a group of people around her who care and help. These relationships keep the change process alive.

Note that this network of trusting, supportive relationships won’t always include the people closest to a person in her everyday life. In fact, sometimes those who are closest to us may not be supportive of a particular change we want to make. That doesn’t mean they become less important in our lives. But perhaps they’re not who you’ll turn to for help on that particular change effort. As our good friend and colleague Daniel Goleman has said in his books and papers, some written with Richard, although emotional and social intelligence is needed at every stage in coaching, establishing and maintaining resonant relationships is perhaps the most crucial.13

Such was the case for Melvin when he decided to make a significant career and life change, leaving the corporate world to pursue a PhD and ultimately a career in academia. His wife was his closest and most important relationship, but she was not nearly as excited as he was about the possibility of the change he was contemplating, nor did she have the personal experience and insight into the steps he would need to take to make it happen. He therefore needed to also identify others in his network who might provide relevant coaching and support. Melvin reached out to an old college classmate who’d recently left a career in marketing to pursue her PhD. He also turned to others who had made a similar career shift—including other individuals who were married with children—with whom he could share some of the specific issues of balancing family obligations while transitioning from a corporate job to academia. While Melvin’s wife remained the focal relationship in his life, providing support in other areas, his expanded network of trusted supportive relationships helped facilitate his career change effort. Each relationship offered a different perspective and played a unique role in helping him with his desired change.

Such networks of trusted supportive relationships can also help us move forward if we become sidetracked or lose energy or focus around our desired change efforts. For example, a senior executive at a major US financial institution for whom we provided leadership training and executive coaching told us he viewed his identified network as “accountability partners.” He asked the people in his network not just to encourage him, but also to support his change efforts by holding him accountable to working on the changes he desired to make.

The coach and these other resonant relationships serve many purposes. In addition to support, one function is what we call reality testing. This means helping people get beyond their own blind spots. David Dunning of Cornell University, who studies the process of self-deception, has repeatedly documented how people tend to not know what they don’t know.14 Specifically, without conducting reality testing of other perspectives, people often create delusional misinformation about their own—and others’—expertise and capabilities.

how coaching with compassion works

For nearly three decades, we’ve been training coaches with an approach based on the Intentional Change Theory, which embodies coaching with compassion. Again and again, we’ve seen individuals make profound and sustained changes in their lives after being coached in this way. But why and how does it work? And what makes individuals more likely to make and sustain changes in their lives when they are coached in this way?

A number of answers come to mind. For instance, when we use a compassionate approach to help people move toward a self-defined ideal image of their future, our research shows they’ll likely change in a sustainable way—far more than when they are told or feel that they have to change. (Of course, it’s also possible that people will make a sustained change when it’s required, as long as they also feel a genuine, internally driven desire to make that change.) The key here is that the desire to motivation for change has to outweigh the obligation or motivation.

Recall Emily Sinclair, the soccer player we described in chapter 2. She felt that she ought to put her full attention and effort into developing her skills as a soccer player. It became obvious to her coach that there was something missing from that effort, however. When she shifted her focus to running, which in her heart was what she really wanted to do, her sustained effort to develop as a runner and the result she enjoyed were at an undeniably higher level. Melvin felt that he ought to spend more time focusing on his research agenda. Yet his department chair and others in the school saw clearly that he continually spent time on activities that took him away from his research. When he formally shifted his focus to his teaching and speaking opportunities—what he discovered his heart was telling him he really wanted to do—he flourished in that space. The fact is, individuals most often change sustainably in ways that they want to change, and not in ways that they or others believe that they ought to change.

But there’s something else at work here. It turns out that a set of emotional, hormonal, and neurological processes underlie what happens when a person makes sustained change that’s driven by a true inner desire. And these are different processes from changes attempted when someone is merely responding to an outside expectation. We will discuss this in greater detail in subsequent chapters. For now, note that coaches and helpers of all kinds play a big role (knowingly or unknowingly) in triggering those emotional, hormonal, and neurological states, and these have a significant impact on an individual’s ability to change or even perform.

When coaching for compliance, even if it is well intentioned, a coach often elicits a defensive response from the person being coached. People tend to experience this as a stress response accompanied by negative emotions and activation of the sympathetic nervous system, which in turn triggers a number of hormonal processes that essentially shut down the capacity to learn or change in any way. At this point, people have been thrust into the zone of the negative emotional attractor (NEA), which we will cover more in chapter 4. For now we’ll say that in this state, people are in survival mode. Their creativity and openness to new ideas are greatly diminished, and the likelihood they’ll make or sustain behavioral change is extremely low.

Think about a child in Little League Baseball playing third base in the late innings of a close playoff game. When he makes a throwing error to first base, his coach yells and screams, telling him how stupid and costly a mistake that was and questioning how he could mess up such a simple throw. Suddenly, the horror the player already feels from having made the error is magnified by ten. His stress level goes through the roof. He’s now terrified, with a racing heart and shallow, rapid breathing. All he can think about is the gravity of his error, and he prays that the next ball doesn’t come to him. But of course, it does. He’s now so paralyzed with fear from the corrective “coaching” he’s just received that he bobbles a routine ground ball, making yet another error.

This is what often happens with coaching for compliance. Although we may think that we are helping individuals improve their performance, instead we trigger or sustain a stress response. This invokes the NEA, activates the sympathetic nervous system, and actually makes them physically less capable of learning, developing, or favorably changing behavior.

Coaching with compassion elicits a very different response. With a vision of a desired future state and focus on strengths rather than weaknesses, positive emotions are stimulated rather than negative. The energy and excitement around this positive emotional attractor (PEA) activate the parasympathetic nervous system, which sets into motion a set of physiological responses that put the person in a more relaxed and open state. Creative juices flow. New neural pathways form in the brain, thus paving the way for new learning and sustained behavioral change to occur.

Let’s return to our Little League Baseball player, but with a different coach. Upon seeing the boy make a throwing error in the big game, the coach calls a quick timeout. He visits the player at third base, telling him that it is okay. He reminds him to take a deep breath, relax, and get ready for the next batter. He reinforces the fact that he is one of the best third basemen in the league and tells him that he’s made that throw a hundred times. All he has to do is think about his mechanics and see himself making a good throw, just as he does 99 percent of the time. After that coaching and reassurance, the player is now calmer, more relaxed and ready for the next play.

This time when the ball comes his way, it’s actually not a routine ground ball but rather a tricky play. He won’t have time to glove the ball and still make the throw to first. He has to get creative. Thinking quickly, he grabs the ball with his bare hands, sets his feet, squares his shoulders, and makes a beautiful, on-target throw to first base for the out. Because his coach helped him reflect on his strengths and envision a positive outcome, evoking the PEA and activating his parasympathetic nervous system, he was able to relax and think more clearly and creatively.

Although a variety of studies have explored what style of coaching helps individuals the most, the difference we are discussing is deeper than behavioral style.15 For example, our colleague Carol Kauffman advocates using flexibility in integrating various approaches from behavioral and psychoanalytic therapy to coaching.16 A major difference is that we are examining what the individual experiences, not just the coach’s intention.

As we’ve said, we have collected considerable empirical evidence supporting the effectiveness of coaching with compassion in bringing about sustained desired change in individuals.17 We have also gathered over time a great deal of anecdotal evidence on the power of this approach in helping individuals make meaningful changes in their lives.

For several years, we collected responses from managers, executives, and advanced professionals on the reflection and application exercise in chapter 2. When these individuals shared reflections about the people who had helped them most in their lives, they were consistently filled with warm, emotional reactions to those memories. Whether tender or challenging, those moments had a lasting impact largely because of the genuine care and concern the individuals showed them. When we coded these shared reflections for which aspects of the intentional change process were primarily involved, we found that approximately 80 percent of the moments people recalled involved someone helping them tap into their dreams, aspirations, core values, and/or strengths. In essence, they helped them discover their ideal self or appreciate their distinctive capabilities.

Conversely, when we asked them to recall people who had tried to help them, but who were not necessarily successful in doing so, we found that well over half of the instances recalled involved someone giving them feedback on areas where they needed to improve. In other words, they focused on their gaps or weaknesses.18 Given these observations, it is no surprise that so many individuals fail to change in sustained ways. Too often, the people trying to help them unknowingly trigger a stress response, tipping them into the negative emotional attractor and making them physically less capable of making change.

To be an effective coach or successfully work in a helping role of any kind, you can’t get around the critical role that emotions play in people’s change efforts. Coaches need to become experts at recognizing and skillfully managing the emotional flow of the coaching process. This requires being tuned into the person being coached, creating a sense of synchrony that allows you as a coach to read as well as influence the emotions the person is experiencing. Additionally, given the role of emotional contagion, being able to effectively manage the emotional tone of the coaching discussion also requires having an awareness of one’s own emotions—and recognizing the impact that they can have on the person being coached. We’ll discuss this more in chapter 7.

In this chapter, along with the reflection and application exercises, we introduce conversation guides. Like the exercises, the guides are designed to have you reflect on the topics discussed in the chapter. However, since meaningful conversations are at the heart of helping, we strongly encourage you to find others with whom you can have conversations about these topics; the conversation guides are designed to help start those exchanges. You may also find it helpful to discuss the reflection and application exercises with others. The more you discuss these topics with others, the better!

In chapter 4, we will continue exploring the PEA and NEA and look further at how the brain affects the coaching process.

key learning points

- Coaching with compassion begins by helping a person explore and clearly articulate her ideal self and a personal vision for her future. This often means helping her tease out the distinction between her “ideal” self and “ought” self.

- To help individuals build self-awareness, ensure that they consider their strengths and weaknesses in the context of their personal vision statement first. A useful tool for this is the personal balance sheet (PBS). The PBS guides the individual to consider assets (strengths) and liabilities (gaps or weaknesses). To ignite the energy for change, coaches should encourage those they help to focus two to three times more attention on strengths than weaknesses.

- Rather than creating performance improvement plans in which individuals focus on their shortcomings, the learning agenda should focus on behavior changes that they feel most excited to try—changes that would help them grow closer to their ideal self.

- Coaches should encourage individuals to practice new behaviors beyond the point of comfort. Only continual practice leads to mastery.

- Rather than relying solely on a coach for support, individuals need to develop a network of trusted, supportive relationships to assist them in their change efforts.

- Coaches must be aware of and effectively manage the emotional tone of the coaching conversations.

reflection and application exercises

- Thinking back over the course of your life, what were the situations and events in which you truly acted “on your own terms” and didn’t feel you were purely reacting to others or doing what others wanted you to do? Have there been times where you have felt genuinely self-directed in pursuit of your own dreams and aspirations? Was there a shift in life philosophy, personal values, or general outlook that preceded these times? How did these times in your life feel?

- Have there been times in the past where you felt a disconnect between the person you would like to be and the person you were? Have you ever seriously compromised your values to please others? Have you ever seriously compromised your own values or ideals for the sake of being practical or expedient? How did you feel in such moments?

- Think about a coach or someone else who brought out the best in you. How did you feel about what you were doing and why you were doing it?

- Think about a coach or someone else who tried to get you to do something you really didn’t want to do. How did that feel? Did you change in the requested direction? If so, how long did the change last?

conversation guide

- When in your life have you attempted to coach or help someone change his behavior in a way that you wanted him to change? How was that received? How much did the person change? To what extent was that change in behavior sustained?

- When have you had conversations aimed at helping people discover and pursue something they were really excited to do? How did those conversations go? To what extent did those people make sustained progress toward their desired change?

- What type of coaching do you observe most often in your organization—coaching with compassion or coaching for compliance? Why do you think that is the case? What is the collective impact of this on the organization?