Reel 8

Sound Thinking

Sc. 1 Introduction

The case studies in Sound Thinking: Thoughts and Analysis encapsulate an elemental characteristic of “the end of the analog age”: specialists divided and re-divided their crafts, re-organized and re-combined the existing tools of artisanship, juggled multiple formats for recording, editing, and playback, always aspiring toward more perfectly immersive movie sound.

The Exhibition end: Scale and virtual reality

When each generation experiences technical advances on the exhibition side of entertainment, that technology can itself become a lively part of the popular culture. In 2016, a good 3-D adventure in Atmos and Imax is usually a good bet for box office. Young audiences have to be lured into the big, dark theater just as postwar families were seduced by Cinerama’s ingenious synthesis of human peripheral vision. While our undergraduates’ critical précis of a new kind of show might be as limited as the exclamatory Awesome!, their enthusiasm and word-of-mouth via social media will usually ensure a new exhibition format’s popular success, and this has created a solid new building block in the history of entertainment media.

Future media scholars will have a bounty of existing reception theory to apply to new movies in Dolby Atmos, or to whatever inventions might surpass Douglas Trumball’s latest super-high-resolution moving images, largely because we perceive and receive new systems differently, entirely apart from the narrative content. Nobody would care about new entertainment technology if not for its potential to communicate sensory data to the brain through some path that improves upon the earlier paths. Looking for a Road Less Traveled, and keeping in mind that entertainment can stimulate something akin to an altered state of consciousness, entertainment engineering consistently explores for shortcuts toward perfect virtual experience.1

A mirror to the expansion of the big screen, there is already some shrinking of entertainment to the scale of smart phones. Audience preference for single-user entertainment (such as we now play on personal mobile equipment) has some ancient history as well, and changes of size will really provoke change in the nature of entertainment’s content.2 Cinematography, editing, directing, and sound design will all evolve new aesthetics for the mobile personal screen and for ear bud audio, just as they once expanded their scope for the big theater. Design for small-image production and exhibition will inevitably challenge critical theorists to analyze it.

The post-production end: Expansion of crews and horizontal workflow

Early in the 1980s Hollywood sound editing crews commonly took on a feature film one reel (1,000 feet, running ten minutes) at a time. Four accomplished sound editors could cut all the dialogue, FX, BG’s, and Foley for three reels each, or some such combination comprising twelve final reels could be worked out. This linear workflow was neatly described by our colleague Norval Crutcher,3 in Vincent LoBrutto’s Sound-on-Film.4 In Crutcher’s time, sound editors were film-editing generalists who would sometimes specialize in sound editing.

But what happens when the Reel 3 editor uses a different FX for the protagonist’s front door, and that door reappears in Reel 5 with an entirely different sound? A good supervising sound editor supplied the crew with detailed lists connecting particular library sound FX to use, matching each to particular sound events (a “cut-list”), and such mistakes could be rectified in the cutting rooms, cheaply enough. But with the assignment of cut tracks to dubbing units, and of dubbing units to mixer’s fader channels, the effect of single-reel editing was often to jumble things up for the already-harried re-recording mixers: valuable stage time could be wasted when the Reel 3 editor put her front door on FX track 3, but the Reel 5 editor put his front door on track 7. The re-recording mixer could certainly cope with this adjustment, but it was less than efficient for setting up each reel to be mixed. These two types of by the reel discontinuity (sound effects choice and assignment for dubbing units) would routinely make workflow much more complicated when editors began conforming reels for late picture changes. As if selecting, editing, organizing, and mixing thousands of tiny pieces of mag did not make enough of a skirmish, picture conforming would lob hand grenades into the foxholes.

A markedly different workflow in the late 1980s had served the San Francisco Bay with more efficiency. For the most part, sound editors would routinely take on responsibility for a given family of sounds, wherever in the continuity of the film they would be needed. In simpler terms, it would become one editor’s job to cut, say, fire, or gunshots, or car skids in every reel of the film. Two distinct advantages were obvious to anyone working in the field:

1000’ film sound units on film rack. Courtesy of Steve Lee & Vickie Rose Sampson, the Kay Rose Archives.

Ready for pick up: sound units with their cue sheets shipping out to the dub stage, Warner-Hollywood studios. Photo by Destiny Borden.

First, a single editor would become the resident expert in the styling of those sounds throughout the movie, subject to approval by a supervisor or designer (for instance, a Richard Hymns or a Ben Burtt in the role of manager/coordinator). If it took three sound effects layers to achieve the right sound for the good guy’s gun, someone could ensure the continuity of that approach, and there might never be an audible mismatch. It is a simple extrapolation from there out to the practice of supervisors charging each sound editor with a number of subcategory sounds to handle in every reel: “Horizontal Editing.”

The second advantage to this work system is most evident when, as inevitably as changing weather, picture changes are committed by film editors and directors. Following the altered continuity of picture usually results in the mindless butchery of sound elements, some time between their original editing and their safe arrival at the stage. Just as often, pre-dubs themselves may be conformed to picture changes and recombined with elements newly edited to bridge the gaps. In any case, for the sound editor handling a film “horizontally,” the changes require less of the ugly M.A.S.H. surgery than was necessary with the older system.

The formerly generalized “sound editor” would not have served any late twentieth century blockbuster’s schedule nor its addiction to sonic detail. But more sound editors, working with subdivided specialties (Foley, Dialogue, ADR, and FX editing, and with a separate music editor’s close connection to the composer) did the job well when coordinated by Supervising Sound Editors. With crews comprising so many moving parts, and under schedule pressure, the “Supes” observed by Moviesound Newsletter sometimes seemed as if they were coaching basketball teams in professional competition.

This section provides a few case studies, comprising four films and two technologies for mixing and playback: Three films, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), Batman Returns (1992), and Days of Thunder (1990), serve here as mile-markers in new methodologies for multi-speaker exhibition, and each movie benefitted from enthusiastic sound editorial crews attempting to push their analog tools to their limits. A fourth film, Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), encapsulates some of the technological conflicts of the era for post-production sound workers. The movie (an enterprise of extraordinarily ambitious artistic goals, even for the greatest American director of his time,) presented logistical challenges that were the consequence of changes in the Industry, having little to do with the film’s artistic goals and their successful achievement. In Digital Editing Meets Mag: Dracula, the newsletter recounted just a few of those issues, recalling gratefully that, as difficult as the job was, the post-production sound team has been amply hailed and appreciated.

Movie sound exhibition presents challenges that might ultimately have been overcome by CDS or Q-Sound. Their histories are both now “cold cases” fading into the obscure corners of film history. Moviesound Newsletter chronicled a promising new enhancement (Q-Sound) for re-recording mixers’ dub stages: A successful Q-Sound might have revolutionized film sound so fundamentally that the entire history of twentieth and twenty-first century theatrical multichannel speaker mixing methodologies would been rendered completely inconsequential. But it was not, and it did not.

Two Moviesound Newsletter articles scrutinized the exhibition debut of the CDS format (which presages the now-standard optical digital formats). The first piece fairly bubbles with anticipation. The second reports on a technological crash, and does so in an unfortunate tone of defeatism. A third article, elsewhere in these pages,5 allows for a more balanced impression of CDS after its demise. Future researchers should probe more deeply into the particular history of at least these two promising technologies and might analyze the art history of the sound design accomplished by all our subjects.

Embodying the enthusiasm of most post-production workers in the late 1980s Ben Burtt was interviewed for Moviesound Newsletter about his work creating the soundtrack for Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) and expressed a good deal about his interest in the exhibition side. It was a “Split-Surround” (the antiquated appellation for “5.1”) mix, and he worked closely with a theater in the San Francisco Bay area to ensure quality exhibition.

Indy Splits Published in July, 1989 (Vol I #5)

Sc. 2 Indy Splits

Split-Surround is a technique that divides a theater’s rear signals into separate left and right material, changing 6-track stereo to 7-track. Top Gun, Star Trek IV, Explorers, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Apocalypse Now, The Jazz Singer, and The Black Cauldron were edited, mixed and released with “Splits” in the best theaters. It’s controversial in the sound community… may not be worth the trouble. MSNL tech consultant Larry Blake argues that if you can tell the difference between left and right surrounds, the FX are gimmicky and draw attention away from the overall sound-staging. Blake would prefer to see that extra effort directed toward “discrete six-track” instead of the “spread-six” in customary use today. We’ll present a point–counterpoint debate on this subject soon. Regardless of your preference, these techniques don’t play back in home systems, and thus make Going Out To Movies, especially big-scale movies like Indy III, a sonic imperative!

Ben Burtt, best known as the sound designer of George Lucas’ Star Wars trilogy and the three Indys, was very happy to work with split surrounds for Last Crusade. He told us recently, “I loved doing the gun battle in the canyon because there was no music, and with split surrounds the gunshots are moving all around the room, with ricochets going from corner to corner.”

In Marin County, home of Skywalker Ranch, Indy III opened in split surrounds at the Corte Madera theater, which had just converted from mono surround. Ben is frustrated that Lucas’ films never open in THX theaters in Northern California, though ironically, THX sound systems are a Lucas product. Where a film opens is the result of deals made in the film distribution business, and has nothing to do with the concerns of artistic people making movies. The Corte Madera is a clean, good-sounding theater, excellently run. “We’d love to get THX in there,” Burtt told us. “They have upgraded their amplifiers recently, and now have split surrounds… but it could be more complete. They have great projection there, the last theater in Marin to use the traditional two-projector changeover system, and it’s large enough to get that Lawrence of Arabia feel… big screen, big image, big sound.”

“I think the Corte Madera has four surround speakers,” Ben went on, “so you don’t really get a shell sound. By that I mean some theaters have a more localized feel in the surrounds… your experience depends where you sit. Another approach is to have a lot of little speakers all around (the sides and rear), so it’s more like a necklace around the audience, or like a hemisphere, the bottom of which lies against the screen. That’s a more generalized, ambient kind of surround.”

“Indy III was as much a film soundtrack as it was a library of sounds (laughs). It had everything… horses, guns, tanks, a zeppelin. All my life I’ve wanted to work on good, solid action-adventure movies. The Indiana Jones films are eclectic retrospectives of things that I would have loved to see and do when I was 12 years old. Each reel was almost a complete change of sound, in the sense that you’re in an exotic new location. You had a major chase in a different landscape with different kinds of vehicles in each reel. An assortment of weapons and natural catastrophes: earthquakes, storm at sea.… You look at each reel and that requires conceptualization and editorial work and mixing in a very detailed way. So the thing I probably enjoyed most was the scope of the material needed. I generated about 40 tapes, each with about 20 FX made up specifically for this film. That includes everything from weapons to backgrounds, mixes of birds, etc.”

“We’d laid out in the music spotting sessions what scenes would not have music, so that was a chance to do a lot of FX by themselves. John Williams was open to a better balance (of FX and music) than even he was allowed to do. I see music being more effective when you have less of it, when it’s not trying to stay “busy”. Of course I’m speaking with the sound designer’s bias. Look at Lawrence of Arabia. You have big music scenes and big FX scenes. They took their turns. But you hardly ever have a combination.”

“I had always wanted to do a film with a zeppelin, even searched for years for a bona fide recording. There really are none, except for the famous radio broadcast of the arrival and destruction of the Hindenburg. You can hear the hum of the engines, though not very distinctly, before the disaster. What we ended up using was a small “ultralight”, with its low-powered motors, and we slowed it down. One nice thing about the ultralight is that it would pass by very slowly, so the doppler-effect pitch change would happen slowly. Now if you record a nice airplane, like a P51, you want to hear the different parts of the motor turning, the spinning tip of the blade, the pinging and whining of the engine. But if you slow that pass by down to match the speed of a zeppelin, it won’t have the quality… would get muddy. A nice thing about zeppelins is they have two sets of engines, front and rear. So you get a pass by of the front engines, and while they’re going away the second set is approaching! If you see a British film called Zeppelin, a mono film from the ‘50’s, they had a very nice succession of pass bys. In our film, in the dining room, you can hear the motor sound all spread around the theater. Zeppelins used large diesel engines with a prop that was 12 or 14 feet in diameter. But they turned very slowly, paddling the air. So it would have been very quiet to the passengers.”

“I had recorded tanks about 10 years ago between films, just for the library. I hung around Ft Hood, Texas, and did weapons, infantry things, helicopters, and tanks. I rode in a tank, recorded inside and outside and firing. Tony Daw, the recordist on the film, had worked with me on Jedi. He knew how important it was to record these things properly on location. He spent a day recording the aluminum tank they built for the film, which had some powerful diesels in it. So we mixed that with material from real tanks, which had better tread sounds, better metallic squeaks. The production tank had a number of special efx modifications. I think it had rubber tread, so they didn’t rip people to shreds.”

“During the fight on the Portuguese freighter, the storm’s waves came from Ocean City, NJ. One day I was wandering on the beach, hiding my recorder from my wife Peg. She’s very supportive, but she doesn’t want me to record on vacation. Got some good crashes on the rocks, then I sweetened them on the synclavier to make them more exaggerated, more powerful.”

“The ‘30’s boats were a combination, like the tank. We didn’t have time on this film to go out and record new boats, but the wooden speedboats you see in the film had good engines in production. I went through the 1/4” production tapes and stole some good “steadys” and pass bys from the 1st and 2nd unit shoots, and from alternate takes. I put them on the synclavier to clean them up, and I cut out the voices, filled in the gaps. I had also recorded a wooden fishing boat in Cape Cod. It had high powered diesels, and I changed the pitch to match those production boats, so it’s a mixture of the two things.”

“The freighter screw was perhaps the most difficult and least satisfying FX on this film for me. You have a scene where the screw is chopping up Indy’s boat. Because they had inter-cut different takes for the final sequence, the propeller was always turning at a slightly different speed from shot to shot, and it wasn’t in the same position. It was varying all over the place! Then you had the problem that the scene became a pivotal dialogue scene. It wasn’t intended to be originally, it was an action scene. But editorially, it became the only opportunity between Indy and Kazim to explain where the rest of the story was going to go. It became a voice-over situation, where lines of dialogue that they had never said were stuffed in their mouths. Originally it was something like, Indy says ‘Where’s my father?’ and Kazim says ‘Let me go!’ Now it’s ‘Why are you killing him?’ ‘Why do you want the Grail?… What are you searching for?… I’m searching for the Holy Grail!’ ‘Why do you want the Grail?’ and ‘What happened to my father?’ ‘I won’t tell you!’ ‘Tell me!’… that sort of thing. They used multiple cuts, repeating the shots to make room for new lines. The scene is so cheated that it’s very frustrating editorially. By all rights it could’ve been a very tasty scene for sound, a giant prop splintering a wooden boat. You want to have the eye go to the propeller and hear it. And Johnny Williams scored it so the music is appropriate for the climax of a long chase, with the orchestra blasting away! So we had some real compromises to make that part of the track work.… To actually cut the propeller, we tapped the film with grease pencil on the movieola, the way music editors do, to find the average frame rate, the rhythm that seemed right to the eye. We used that as a click-track, cut different sounds on the Synclavier and played them at that rhythm. Those were splashes, wood hits, a piece of snapping plywood that I liked. I repeated these but changed them slightly, so it didn’t sound phony. It’s a mechanical action on the screen, but you don’t want it to sound mechanically made, or it’s no longer dramatic!”

“There was no production sound of those rats at all. Essentially the overall rat sounds are chickens. I was trying all different animals and pitching and speeding them up, to make rats sounds. I wanted a busy kind of sound and squeaking kind of sound. I already had a “chicken riot” on tape. Remember the chickens on board the tri-motor plane in Temple of Doom? We had some out-takes from that material. I sampled it and played it on the keyboard and it felt like rats. The individual rat shrieks and screams are mostly other mammals sped up. There’s one dog I recorded. He growled in a way that, when sped up, becomes a vicious-sounding rabid rat. There are also pigs in there and some lemurs. But, believe it or not, the chickens are the basis for the rats.”

“With such an experienced team going into this, I could focus on creative aspects of the sound, rather than be bogged down in administrative stuff. So it was a very satisfying project all around.”

Ben Burtt became interested in split surround when working on the large-format Imax films “The Dream Is Alive”, “Niagara”, and “Alamo”. The thirty-foot high screen requires special attention to sound placement, including an upper center position. We’ll get involved with Ben’s Imax work as a sound designer, picture editor, and director of the upcoming “Blue Planet” in a future issue. —ed.

Post-production and exhibition developments were progressing along parallel and compatible lines, but each with its different technical concerns.

Throughout their co-supervising of the sound editing for Batman Returns (1992) the author and Richard Anderson were aware of the studio’s intention to distribute the film in a four-channel surround format version using the state-of-the-art Dolby SR (“Spectral Recording”) system. The format offers the most clarity and dynamic range possible with an analog track, and that system is still in use today on film prints, as an analog alternative to digital reproduction. All the tracks were edited and mixed with both 4-channel (mono surround) and 5.1 (stereo surround) release in mind, as was common practice on big-budget films by 1992, and consequently the re-recording mixers made a 6-channel mag print-master (with SR encoding for the highest quality).

This methodology had become common practice in Hollywood, as sound design teams perfected their techniques with mostly analog tools, experimented with a few digitally-enhanced elements to be incorporated in the final analog tracks, and worked with mixers to create highly dramatic sound masters for analog release, and had additional material available to upgrade their shows to 6-track exhibition. Usually the bigger films would go out in limited 70mm versions, which accommodate six discrete tracks.

A happy outcome for the crew was the release of Batman Returns in the new Dolby SR-D format. The system had been secretly tested with two feature film releases previously, but Warner Bros. was confident enough in SR-D’s stability to announce the new format and promote it publicly. Today this digital-optical track format is standard (and will be, for the short remaining life of 35mm film projection) and is called “Dolby 5.1,” formerly “Dolby SR-D” or “Dolby Digital.”

Holy Split-Surrounds, Batman! Published in Summer, 1992 (Vol II #2)

Sc. 3 Holy Split-Surrounds, Batman!

Digital Update

Holy Split-Surrounds, Batman!

System Officially Out of Dolby Closet

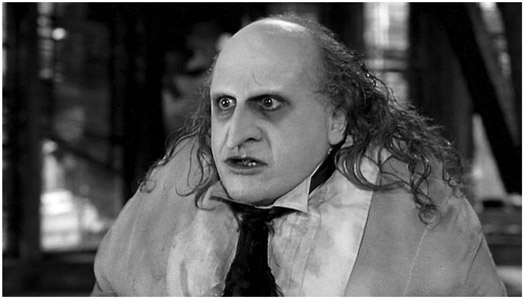

Batman Returns, directed by Tim Burton (1992). (Warner Bros.; Burbank, CA: Warner Home Video, 2009), DVD.

Tim Burton’s Batman Returns will be running in several major-market theaters in the new Dolby SR-D format. MSNL Vol I #19 discussed the first industry demonstration of the digital-optical process, which loads all the audio data for six channels of dynamite sound in between the sprockets of a 35mm release print. SR-D exhibits all the punch, clarity, and stable image-location (including discreet left and right surrounds) that Optical Radiation Corp’s Cinema Digital Sound processed so successfully. Dolby’s proudest selling point, unlike CDS, is that in the event severe glitches occur in the digital system, the projector’s audio automatically switches to the Dolby SR optical analog track.

SR optical prints have dynamic range and headroom that rivals 70mm magnetic six-track. Although both Dolby SR and the older Dolby “A”-type optical tracks are based upon a “4-2-4” matrixing system, (and thus haven’t the same kind of image that discrete six-track recordings do,) the SR prints run rings around “A” prints. MSNL readers know that optical tracks are amenable to the film industry’s need to keep distribution simple. Magnetic tracks sound great, but make shipping and hardware complicated. Sources tell us that France is fooling around with digital film tracks on compact disc, (similar to Showscan’s audio). But that requires “double system” distribution. And what if someone plays the disc for reel 3 with the picture of reel 4? Separate discs with film? Vitaphone was old hat sixty years ago.

A digital optical track has many advantages. It looks like Dolby SR-D really fills the bill, and theater owners would hope it fills their seats! Although Star Trek VI and Newsies were run in Dolby SR-D, the releases were a classified test; Dolby cautiously did not publicize the fact. Batman II is the first movie being openly advertised with SR-D in selected theaters. MSNL can brag that its editor and his supervising partner, Richard Anderson, brought SR-D to the attention of Tim Burton and Batman II’s producer, Larry Franco. Their enthusiasm for the “Big Sound,” and the cooperation of all the Dolby and Warner Bros., post-production people brought SR-D into the mainstream for the Summer of ‘92.

What’s Q-Sound? Published in October, 1989 (Vol I #7)

In What’s Q-Sound? the journal shared with readers some of the buoyant anticipation shared by audio insiders for an altogether radically new mixing format with which “sound can appear at a single point anywhere in the room, completely liberated from the speakers.” Skeptical post-production workers had been impressed by demonstrations, and many in the community began to chatter about Q-Sound as a panacea for movie exhibition’s perfection. Attaining complete control of audio images in any movie theater tantalized sound workers and movie fans alike. It could have been the “Zipless Fuck”6 of film audio.

Sc. 4 What’s Q-Sound?

What’s Q-Sound?

Maybe it’s an audio spying device cooked up by the gadget-man at MI-5 for the private use of James Bond. Maybe not. But what would you come up with if you had a chance to make first-class movie theater sound be even better? If insider excitement is anything to go by, the advent of Archer Communications’ Q-Sound might be the first course of quite an audible feast! We spoke to Chris Jenkins, dialogue re-recording mixer for Todd A-O Glen Glenn Sound in Hollywood, who represents the movie soundtrack branch of Q-Sound’s application efforts. (The technique will also be applied to the recording industry, TV, and video games.) Jenkins, whose movie credits include Out of Africa, To Live and Die in L.A., U-2’s Rattle and Hum, Big, and Body Heat, recently mixed Star Trek V, and recorded a demonstration of Q-Sound using the Star Trek tracks. It wasn’t part of the final film, but we expect Q-Sound in a major movie sometime soon.

(MSNL #6 reported that the technique was slated to debut in the Joe Dante sequel to Gremlins, but that can’t be confirmed.)

Danny Lowe and John Lees, a Calgary engineering and music team, have discovered a set of phenomena that allow sound mixers to steer sound effects and instruments in three-dimensional space. According to Jenkins, sound can appear at a single point anywhere in the room, completely liberated from the speakers. How does this differ from Dolby Surround and Ultra Stereo? Those are ambient techniques, which do a marvelous job of placing us inside a sonic environment. Every MSNL reader knows how much that enhances the audience’s involvement with a film. Normally, sound can be placed anywhere on the movie screen, and be modified by sound in the surround speakers. Keenly observant fans will note that mixers can balance some sounds delicately between one of the front speakers and the surrounds, and achieve a kind of perceived pulling away from the screen as an occasional special effect. But Q-Sound is listener-oriented, specialized in focusing a single sound or group of sounds anywhere in the range of directional hearing.

The idea is that each listener perceives sound from a “personalized” position: If a sound effect mosquito is dive-bombing your left ear, it’s also getting the people across the theater in the left ear. We would have thought this could only be achieved by making binaural recordings and giving everyone a set of headphones, but Q-Sound will make it possible with existing theater speaker systems.

Chris Jenkins explained that the process takes place in the mix-down (in the case of the music industry), or the re-recording mix (in the case or the film industry.) Any tape, film, or laser medium will play back properly recorded Q-Sound. The only exception is vinyl discs. (Another sad nail in the coffin of “records”.) Because the secrets of Q-Sound are concentrated on the recording-mixing side, the phenomenon is independent of any specialized hardware in playback. So any existing home stereo or theater audio system should present its startling effects. Jenkins told us that the effect can be used in two differing basic ways:

- A sound is localized as a coordinate in relation to 360 degrees around the listener’s head, in which case you could turn away from the sound (as you perceive it) or

- A sound is localized in such a way that if you turned your head, it would travel with you.

Perhaps this would be a little more like the headphone experience. But we have been speaking of individual sonic cues or events. What if one “spot” sound moved about your head while most of the rest of the soundtrack was played on the front and surround speakers in the traditional way? Theoretically, any number of Q-Sound events could be programmed with or without the traditional theater sound as a reference point. The Q-Sound layers could themselves be used to emulate traditional ambient theater sound, or to enhance it, or to separate a special effect from its boundaries. Separate Q-Sound points could be steered independently, could move in opposition to each other, creating incredibly complex sound events.

Although not slated for any particular feature film soundtrack, Q-Sound is ready to go into post-production with the right project. Jenkins told us that it’s been well-tested in the analog mode of audio. We’re waiting now while the system is re-engineered for digital recording’s different concerns. Obviously, that will insure its success in all kinds of entertainment software.

Does any other research in the acoustic and audio fields come close to the mind-blowing potential of this new tool? In conjunction with or independent of existing theater systems, Q-Sound could place us even more deeply into the sound stage of movies. Anyone who’s auditioned Carver Sonic Holography or Polk SDA speaker systems knows the strange impact of sound seeming to float away from speakers and create itself in free air. What are the aesthetic ramifications of Hollywood’s potential love affair with Q-Sound? Heavy-handed mixers and crass producers could easily over-use the new tool, so we might see some goofy, gratuitously gimmicky sound tracks. The first stereo features had ping-pong dialogue that we’ve learned to live without. We know that 3-D and other trick visual effects have limited many movies to the realm of the camp and quirky.

MSNL looks forward to the testing and acceptance of Q-Sound in Hollywood soundtracks. Once we get past the Dr. Tongue’s 3-D House of Soundtracks phase, when we have endured some sonically ridiculous remake of William Castle’s The Tingler, we’ll be ready to use the tool in more subtle ways. The precision and versatility of Q-Sound, and especially its compatibility with current surround-sound theaters, will allow it to become a legitimate creative tool in the kits of re-recording mixers. It will be good if sonically literate directors will learn to think of Q-Sound’s ability to enhance their story-telling, and if gimmicky producers restrain any compulsion to use it for a sideshow.

Cinema Digital Sound Introduced Published in May, 1990 (Vol I #12)

A short comparison between the movie industry’s dominant exhibition formats, 35mm and 70mm, and consequently between magnetic and optical sound reproduction’s inherent advantages, helped Moviesound Newsletter readers to put discussion of a radically new format in perspective. Expectations in the sound community were dulled by one unfortunate showing, but only because no backup prints were available to support the new medium as an alternative to digital playback. The last iteration of film projection prints (which are giving way to projection of digital files) carries Dolby Digital, SDDS, and DTS digital media printed optically (although the DTS optical stripe actually represents SMPTE time code, not really audio media) on a single ribbon of film, along with the printed picture. Dolby SR stereo variable area tracks, along for the ride with their digital-optical brethren outside the film frame, are the last act of high-quality analog audio for film sound exhibition, and are engineered to automatically and seamlessly replace any lapse in the digital formats’ performance. It may well have been the failure of the CDS system during one crucial screening event that resulted in the standardized inclusion of a Dolby SR analog optical track on all modern multiple-format digital-optical 35mm prints.

Sc. 5 Cinema Digital Sound Introduced

Cinema Digital Sound

New Multi-Track Format To Debut

Hollywood film audio workers emerged with mixed reviews from a demonstration of the new soundtrack technology known as Cinema Digital Sound. Eastman Kodak has teamed up with an outfit called Optical Radiation Corporation to find a way to print compact disc-quality audio data onto motion picture film.

This May the companies debuted their demo reel, which had been mixed to digital tape at Warner Hollywood’s Goldwyn Sound Stage D, the site of Raiders of the Lost Ark, Star Wars, Top Gun, and hundreds of other classic sound mixes. The digital track was then applied optically to the 70mm presentation reel via their new process. 70mm film has always used magnetic stripes to carry the best quality analog soundtracks.

Many of those attending told us that the playback sound was certainly impressive, but some expressed cynicism about the ability of the sound editing and mixing communities to provide digital-pure dialogue, music and sound effects elements on today’s frantic schedules.

Nevertheless, today’s top sound people routinely create tracks with all the clarity and dynamic range audiences expect of the music industry’s CD’s. And MSNL readers know that first-run movie audiences experience that kind of sound in 70mm six-track presentations. The specialized formats Imax and Showscan may use separate multi-track magnetic or 12” laser disc soundtracks as “double-system” sound sources (not on the same physical medium as the picture.) Hollywood looks not to finding the best quality, but to a simple way to distribute and display big sound with the least expense.

The contributions of Dolby noise reduction to 70mm and the innovation of Dolby 4-track stereo for 35mm presentations can never be overlooked. But Cinema Digital Sound seeks to take another leap ahead:

Advantage… 35mm Optical Stereo

The advantage of 35mm optical stereo is that prints can be made in a single pass. Optical sound is applied from the negative in the film printer along with the picture. It’s as cheap to run off an order of 4-track stereo 35mm prints as were the old monaural versions.

Advantage… 70mm Magnetic

The advantage of 70mm magnetic six-track stereo prints is increased dynamic range, frequency range, separation of channels, and the added detail of six or seven possible channels. The whole “stage” is more dramatic.

Disadvantage… 35mm Optical Stereo

The disadvantages of 35mm optical stereo are a slight decrease in headroom, wherein the biggest bursts of sound must be compressed to “fit” in the optical area next to the picture. The complex matrixing of four recorded channels into two on the track and back into four in the theater occasionally results in playback aberrations. Dialogue may be unpredictably “pulled” to the sides by certain combinations of sounds. The rerecording print master has to be made with a Dolby consultant on hand to insure consistent quality. Theaters can fail to tweak their equipment to properly decode the matrix. Theater managers may not care. Sound may seem to come out of the popcorn machine instead of the screen.

Disadvantage… 70mm Magnetic

Magnetic striped tracks eventually wear down, becoming burnished by the very tape heads that read them. They take a long time to print. The 70mm picture is printed and dried, then the magnetic stripes are applied to each reel. These have to dry and cure properly before the six-track magnetic masters are duped in real time to each print, then monitored for quality control. If improperly cured on a tight schedule, “mag” can flake off or record with muddy quality. Optical Radiation’s CDS theoretically can be printed like a 35mm optical track, in a single pass with the 70mm picture. (The company is not ready for 35mm yet.) Their track, instead of an optical squiggle analogous to the movement of sound waves, is made of those millions of invisible little pits that make CD’s and laser discs so data-rich.

Next to the picture is a strip of pink translucency that, held up to a light, makes a spectral rainbow similar to those made by scientific diffraction gratings, or like the surface of a CD. We assume the track is read by a laser head. The single amorphous track holds data for five separate speaker channels, as well as control data tracks. This would presumably allow for SMPTE time-code, MIDI control information, and film production ID codes. They could trigger movie theater events such as curtains, house lights, house music, etc. Most importantly, the CDS track has redundant data that could eliminate the effects of scratches and small breaks in the film. Error-detection makes CD’s and laser discs smooth over surface imperfections by keeping data in a buffer, and releasing only corrected data to the digital-to-analog stage where it “becomes” audio. CDS releases, logically, might have completely intact soundtracks even when several frames of a film print have been completely lost! The highest advantage would be that theater management would be unable to screw up the playback adjustments. There should be no half-tweaked sound systems. The digital sound should either play with wonderful quality, or will not be there at all. The advantages to the industry in printing 70mm without mag striping would be enormous. And they would make those prints if they thought the theaters were there.

Theaters Must Update Projectors

Dr. Dolby’s organization pulled off something of a miracle when, over a period of years, they convinced reluctant theater owners to upgrade their equipment and accommodate a new generation’s demands for high-tech sound systems. Cinema Digital Sound will have to tread over the same path. Owners will be reluctant to change their equipment again, and many pros were skeptical that theater owners would upgrade 70mm projectors for the small improvement to digital sound quality. But they would probably welcome 70mm-style sound were it available on the smaller 35mm prints.

35mm Not off the Bench

If CDS gets moving on 35mm, we may see the studios choose not to print in 70mm at all. 35mm CinemaScope picture is cleaner and sharper than 35 as it’s blown up to 70. If the only reason to release on 70mm is to get big sound, and 35mm CDS optical sounds even better than six-track magnetic, then we’re going to see 70mm disappear fast! It would be wonderful if new productions would be shot in 65mm negative. There’s no better picture in filmmaking. If this new sound format is successful in the marketplace, then interest in the picture quality will be the only rationalization for 70mm’s expense.

—DS

Cinema Digital Sound Falters Published in August, 1990 (Vol I #14)

Sc. 6 Cinema Digital Sound Falters

New System Swings and Misses, Goes One for Two

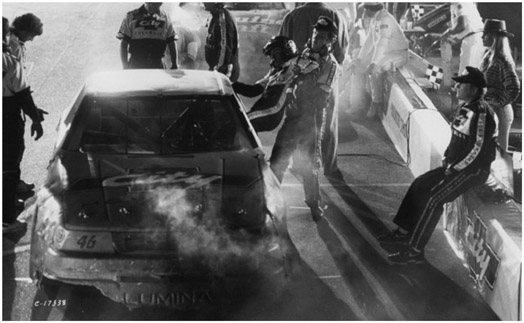

The July 2nd issue of Daily Variety featured a story on Cinema Digital Sound (see MSNL #12) that confirmed some of the rumors we’d been hearing around the cutting rooms: There was trouble exhibiting prints of Days of Thunder with the new, much-heralded optical digital soundtracks. Paramount pulled the prints out of distribution and replaced them with standard 70mm magnetic six-track prints. Cinema Digital’s failure to perform properly was limited to Thunder showings. Dick Tracy, also debuting the new system, has been OK, impressing many with digital’s dynamic range and rock-steady image placement. Optical Radiation Corp and Kodak, who share responsibility for the systems, and the few prestige theaters they converted to play the radically newfangled tracks, must have been deeply embarrassed as they took their prints back to the drawing board.

But MSNL could have foreseen the trouble: Paramount geniuses had hastily made the decision to open Thunder in Cinema Digital. The 70mm magnetic prints were being sounded and shipped out. The dub was finished. According to Optical Radiation’s David Koyle, the studio asked for a digital opening in four theaters with just a week to go. It takes two days inside a movie theater to convert the projectors, install the electronics, and run lots of sound checks. Head mixer Don Mitchell (Top Gun, Glory) quickly made a new digital master. They got the lab running as quickly as possible. Remember, the new CDS prints have an optical track, and ultimately shouldn’t have the long wait for sound transfer and the curing of a wet mag stripe that traditional 6-track 70mm’s have. But the prints still have to be made, and this was a hurry-up order! It was determined that one print could be made in time for one theater, (Westwood’s National) and the other opening venues in L.A. would have to wait. In the wink of an eye, it seemed, the picture had opened and the digital hype was in high gear. June 27th happened to be part of the worst heat wave in L.A.’s history: Most areas in the city recorded 103 degrees for three days in a row. Cut to the projection booth at the National (any booth is likely to imitate a boiler room on the best of days). Extreme close up: Someone has inadvertently pushed the Cinema Digital processing console too close to the wall. Ventilation is cut off. Uh Oh! Ominous sting chord! After the National had successfully debuted Tom Cruise for two shows, the hot processor blew a fuse. The system went down.

Days of Thunder (1990) directed by Tony Scott. © Simpson/Bruckheimer Films

Paramount evidently panicked and gave up on the digital system.

The studio had no stand-by prints available, so the optically-striped CDS 70’s were painted over with mag and released as traditional six-tracks. Paramount was precipitous both in calling for the quick release and then in over-reacting to the overheated machinery. Optical Radiation and Kodak might have been a little wiser about accepting the challenge of a quick release, and probably would not like to go through this again.

New entertainment technology should be carefully nurtured and critically checked, all the more because its success may be vulnerable to publicity. Look at the symbiotic relationship that went sour here: We techies need the publicity of studio hype to get audiences. The Hype Hounds need our product to sell, something technically special to get audiences back into movie theaters.

In a healthy, honest society, Optical Radiation might have told Paramount “We can’t guarantee our system without more lead time.” Paramount might have said “OK, we understand you blew a fuse this time. We’ll give the system another chance, and we have standard prints standing by in case it doesn’t work.”

David Koyle reports that Cinema Digital will be involved with some of the major-studio November releases in 70mm. Their work on 35mm prints is proceeding well.

They’re now testing variations in printer techniques. Beside new features, they are very excited by the prospect of Cinema Digital releases of upcoming restored classics. Spartacus and Fantasia (with a remixed original Stokowski track) are due out next year in one form or another. If they’re going to be presented digitally there’s still time to do it right. Craft takes time.

—DS

Painters, printmakers, and other visual artists have often realized their visions by employing extraordinary combinations of art supplies, commercially printed material, and found objects. It wasn’t long into the twentieth century that such practices had slowly gained acceptance by the art world under the general classification mixed media. Employing new combinations of materials to realize their vision must have been quite liberating to the process of these artists.

Francis Ford Coppola’s realization of the novel from James Hart’s ingenious script7 is a sumptuous entertainment, heaping the film frame with layer upon layer of visual detail, as if the director were a great painter applying thick impasto to canvas with a palette knife. Balancing the weight of High Art with a savvy commercial eye, Dracula is a melodramatic love story supported with dark, passionate music, flavored by ancient Eastern European folklore. Prof. Ament wrote in her essay Sound as Excess:

“There is no doubt that Bram Stoker’s Dracula is a feast of visual and aural stimulation. The entire style of the film recalls German Expressionism, gothic romance, art house eroticism and Italian opera. The costumes are sumptuous and function as the focal point of the sets (Coppola wanted the costumes to be the jewels of the sets and the environs to be the setting for the jewels), the makeup is inventive and fanciful, the acting epitomizes modern melodramatic style, the score employs leitmotifs as signifiers for Dracula and the romantic couple of Mina and the younger count (introduced as a prince), and the sound design at times is theatrical and grandiose.”8

Coppola may have approached his film presentation as mixed media, especially when he eschewed modern computer compositing of visuals in favor of practical sets, camera tricks, and some ingenious and artistic puppetry, but the idea of mixed media in the realm of post-production sound is hardly a liberating artistic choice. At variance with the general requirement of post sound to generate and incorporate material in compatible sound formats and on compatible recording media, the methodologies required for this project were largely improvised in order to solve myriad practical problems. As beautiful as the images are, the picture’s editorial continuity was ephemeral as a mayfly.

Ultimately, Cyberframe computer stations with their magneto-optical drives, Audioframe stations, two-inch 24-track analog tape, DAT cassette tapes, audio CDs, digital samplers and keyboards, 35mm single-stripe magnetic recording film, and 35mm six-track full-coat mag cut with Moviolas and traditional editing hardware were all utilized, often simultaneously, to make the tracks, mix them, conform them to picture, and rerecord them in the final mix. That was mixed media, and not in this case a desirable condition, as the post sound crew tackled the logistical mismatches between Sony Pictures’ and American Zoetrope’s existing equipment and methodologies.

Digital Editing Meets Mag-Dracula Published in Winter, 1992–1993 (Vol II #4)

Sc. 7 Digital Editing Meets Mag-Dracula

Sony Pictures’ — Columbia’s — Francis Coppola’s — Bram Stoker’s — Dracula

This confusing excess of possessives may be a small-scale indication of the complexities that built around the creation of Dracula’s soundtrack this Summer and Fall. There were on this project some monster-sized business-, ego-, and artistic considerations that seemed to drive common sense right out the window. The production was controlled by Columbia/Sony, whose sound department had a desire to showcase the new electronic editing systems they have been using for television and lower-budget movies. Coordination problems arose owing to the desire of Coppola’s American Zoetrope company to do the mix at Coppola’s home, a bucolic winery estate north of San Francisco.

Although Coppola enjoys working with high-tech film and sound equipment, the dubbing room in the attic above his winery provides a less than ideal environment for a complex sound track. A shortage of dubbing hardware would have to be compensated for by countless hours of extra labor from the editorial, mixing, and machine room staffs. Kim Aubrey’s team of engineering and recording specialists created logistical miracles with their equipment, and survived a good deal of stress with intelligence, personal warmth, and humor.

There are names lovingly pasted on the various film dubbers as if they were milking cows in a barn. But these cows have names like “Snappy” and “Stretchy” and “Grinder.”

But the acoustics of the dubbing theatre are hopeless. It is to the great credit of mixers Leslie Shatz, Marian Wallace, Aaron Rochin, and Dennis Sands that they could compensate aurally and have the film sound as good as it does in the acoustic environment of a good theater.

Teams of sound editors worked on the film in July and August, as the sound went through its first few editorial versions, beginning with the film editors’ Version #26. (Bus loads of picture editing assistants had already grown old on the job, before sound people came on.)

Foley and Dialogue editors got down to work using the Cyberframe digital editing system. Production dialogue was loaded onto the computers from traditional 1/4” tape recorded on the set. Cyberframe digitizes those sounds as a set of data files, which the sound editor handles through a computer interface representing something analogous to the editing workbench s/he would use in the “real” world. Sync is worked against a 3/4” videotape.

Foley was performed on the old MGM stage (now Sony Studios) and recorded, as is now common practice, on 24-track tape. Those tracks were then loaded into Cyberframes for editing.

Sound effects were loaded into the Cyberframe’s sister machine, the Audioframe. Audioframe allows for great deal of manipulation, combining and re-design of raw sound effects.9 While it is a creative tool, and was indispensable to the creative effects for Dracula, there is not the Cyberframe-style analog to the tangible world familiar to editors. As a result, conforming versions to each set of complex picture changes was a nightmare of inefficiency.

The edited digital files from Cyberframe Foley were laid back to analog audio in the form of new 24-tracks, sent to the dub stage for predubbing. Edited Audioframe sound effects files were also laid back to 24-track for predubbing. Edited Cyberframe dialogue files were laid back to 6-track magnetic film for predubbing.

These 24-tracks and 6-tracks were mixed at Sony to make Dialogue, ADR, Foley, and Effects predubs on 6-track magnetic fullcoat film stock. Before they could be taken north to Coppola’s winery for the final mix, however, the predubs had to be conformed to match more picture changes. Versions 31 and 33 required such wholesale cuts, juxtaposition of scenes, and new scenes, that many predubs had to be patched, sweetened, and re-mixed to further analog generations. By this time, the electronic editing crew had been replaced by traditional film sound editors, who knew the trade tricks of working out complex sound changes on multi-track magnetic fullcoat predubs.

Versions 35 through 41 were coaxed out of Zoetrope’s broken-down editing equipment in an unheated barn, 1/2 mile down a dirt road from the dub stage/winery. Editors and assistants worked day and night through September and October, to keep up with Coppola’s changes, temp. dubs required for various preview versions, and the ever-changing final mix.

Some problems arose due to differences in the technical working methods common to Northern- and Southern California editors and mixers. L.A. predubs, for example, consistently assign the tracks of predubs to specific speaker channels. (For instance, CH 1 = left, 2 = center, 3 = right, 4 = mono surround, 5 and 6 probably both extra center channels, or assigned elsewhere at mixer’s discretion.) On Dracula, many of the predubs were more of a straight transfer, made with the intention of redirecting some material to specific speakers later in the final mix. Also, to compensate for the shortage of dubbing channels available at Coppola’s, it was suggested that the center channel be eliminated from effects predubs. (In theory, a series of L-R stereo pairs would suffice for predubs. Any effects needed behind dialogue in the center channel might be derived from divergence controls in the final mix.) Following this and some controversy over panning moving effects sources in the predubs, mixers made predubs with widely varying track assignments. This made for much more time spent by editors conforming recut material (They could not attach a piece of predub mixed as L-CR-S-C-C to one mixed as L-R-L-R-C-C, for instance,) and it consumed time on the dub stage.

Although digital editing computers, when properly configured with sufficient hard disc space and RAM memory, should be able to handle any sound editing assignment with panache, those at Sony were not ready for Dracula. The editors had never before had to choke their machines with so much data. There were insufficient hard disc drives and memory available. There was not enough engineering support on for these prone-to-crash computers. The machines were not upgraded to match the demands of the production. Also, the digital editors had to beg, borrow, and steal enough Dolby SR circuit cards to make their lay-backs to tape. As a result, people with pride in their craft often had to work overtime for free.

Digital sound editing machines are not the revolutionary path to efficiency in their field that film editing computer systems have proven to be. When editorial changes are made, film editing computers perform the work of assistant editors: they keep track of the choice of footage from one film negative and one production dialogue track. But new edits affect a sound track-in-progress very deeply: tracks being prepared for mixing have hundreds of interlocking fragments. We don’t know a digital system that makes changing tracks any easier than it would be on magnetic film. Dracula’s original digital layback material was dynamic, clean, and beautifully edited. But it had to be committed to analog premixes eventually. Coppola’s creative process includes endlessly experimenting with his picture; pushing, pulling, extracting different shades of meaning from editing subtleties. In the process of reorganizing and juxtaposing scenes, premixes become battered. Recording quality is inevitably lost through generations of copying. Precision and invention that sound editors work to achieve is compromised with a sudden change in schedule.

We tell this story not because Dracula is unusual. Most films for which studios have big expectations will go through many rounds of changes and conforming. No matter if digital editing is used in the early innings, there is only so much time to make a soundtrack or to change it. Sound editing technologies, at a crossroad in history, are of mixed media. Somewhere in the universe, for every lovingly-handcrafted piece of magnetic film sound that loses synch by mechanical or human slippage, there is a matching piece of electronically-edited digitally perfect sound that gets lost forever in a common hard disc crash. No free lunch.

—DS

Notes

1. A wondrous extension of this idea is the subject of The Continent of Lies (Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1984) the second of James K. Morrow’s thirteen novels. Springing from Morrow’s expertise as a cineaste, it “posits a futuristic entertainment medium called dreambeans or cephapples: genetically engineered fruits that plunge consumers into scripted hallucinations” (as Wikipedia describes it).

2. Popular motion-picture entertainments (as commonly exhibited in novelty arcades via Mutoscope and Edison Kinetoscope machines) were designed for single-viewer machines in the late nineteenth century. Edison was a late adapter to the idea of projecting film images across a room for group viewing.

3. Crutcher and his ex-wife Ethel were highly regarded as personal mentors in the sound editing community. Crutcher trained a lot of good editors, and he facilitated the hiring of many women artisans into what had been something of a “boys club” of audio editing professionals. The couple were among the few founders of the Motion Picture Sound Editors (MPSE) association, which raised the profile of sound editing in Hollywood enormously, especially with its Golden Reel awards.

4. LoBrutto, V. (1994). Sound-on-Film: Interviews with Creators of Film Sound. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

5. See We Chat with DTS’s Jeff Levison in the Talking Pictures section.

6. Please excuse Erica Jong’s vivid and wonderfully idiosyncratic phrase from Fear of Flying (1973, Holt, Rinehart, and Winston).

7. If nothing else, overcoming this epistolary novel’s reluctance to be transformed into cinema in the first place (which needs visual and aural action to tell a story, not thoughtful diaries and letters) is a miracle of craftsmanship.

8. Ament, V. Sound as Excess. Essay, critical analysis of sound design in BSD. (2013, Georgia State University)

9. The Cyberframe and Audioframe systems existed on the same PC-based hardware. Editors could boot up this versatile PC-based workstation in either mode, but not simultaneously. Cyberframe/Waveframe were track editors, giving the sound editor a graphic user interface designed as a metaphorical synchronizer and editor’s bench. The Audioframe editing mode was a wave editor, offering its sound manipulation tools in a DOS command-line environment, not utilizing a graphic user interface at all. Track editing and wave editing software were evolving separately in this period.