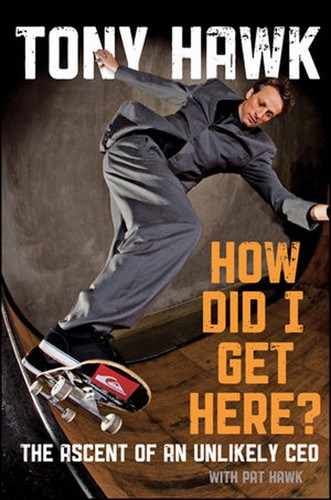

I officially became a professional skateboarder in 1982. I was 14. The moment itself was no big deal. I was at a pro-am contest in Whittier, California, and my main amateur sponsor at the time, Stacy Peralta (co-owner of Powell Peralta), suggested it might be time for me to turn pro, since I'd reached the top of the amateur ranks. When I filled out the registration form at the skatepark that day, I simply marked the box that said "pro" instead of the one that said "am." That's it.

I'd started skating five years earlier, when my brother Steve gave me one of his old boards. I took to it quickly, and lucked out in two big ways. First, there was a good skatepark (since demolished) just a few miles from my house in San Diego. Second, my parents were the kind that steadfastly supported their kids' passions, no matter how far they veered from the mainstream. My sister Pat loved to sing; my dad managed her rock 'n' roll band and drove her to gigs. Steve loved to surf; my parents would get up at dawn to drive him to the ocean, 10 miles away.

My first board.

Note

To: <[email protected]>

Subject: GO F*%K YOURSELF

TONY HAWK HAS REALLY HIT A NEW F*%KING LOW. I WAS AT WALLY WORLD TODAY BUYING TOOTHPASTE, AND THERE THEY WERE–A WHOLE SHELF OF JUNK TONY HAWK SKATEBOARDS. COME ON TONY, LIKE YOU DON'T MAKE ENOUGH MONEY–NOW YOU GOTTA SELL JUNK SKATEBOARDS AT WAL-MART? SO MUCH FOR YOUR INTEGRITY. GO F*%K YOURSELF AND YOUR 900.

They didn't have much money, but they were there for us in every way.

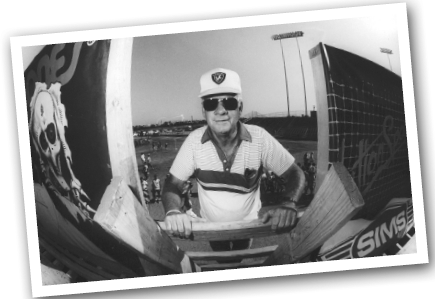

My dad, Frank Hawk.

Once I started winning amateur skate contests, my dad, Frank, diverted his enormous energy into helping the sport become more organized. He and my mother, Nancy, founded and ran the California Amateur Skateboard League—which, amazingly, is still in existence, and now, even more amazingly, includes a parent-child division. Dad also created skating's first truly successful professional circuit, the National Skateboard Association. (The NSA eventually morphed into World Cup Skateboarding, which remains the governing body for both the X Games and the Dew Tour.) He also built countless ramps for me over the years. He died of cancer in 1995, one month after watching me win gold during the inaugural X Games. My mom's still going strong, and lives a couple of miles from me in northern San Diego County.

That day in 1982 when I officially turned pro, I harbored no fantasies about making a living as a skateboarder. I think the first-place prize money at that event was $150. Someone else won it. Even when Powell Peralta made me an official member of its team of pros, called the Bones Brigade, and started selling boards bearing my name (and an amateurish hawk graphic), I had zero visions of wealth. One of my first royalty checks, dated April 19, 1983, was for 85 cents. I still have it.

Things started to change after Stacy directed and released the Bones Brigade Video Show in 1984. It was the first direct-to-video skate movie ever made, and it helped trigger a boom for the skate industry. Suddenly, I was receiving royalty checks for $3,000 a month. The amount quickly grew. By the time I reached my senior year of high school, I was making around $70,000 a year. My dad believed it was likely to be a short ride, and he encouraged me to invest some of my income. My sister, Pat, who did my taxes (and is now my manager), told me I needed a write-off, so I bought a house in Carlsbad a few months before graduation. I was only 17, which meant that my dad had to co-sign the loan.

As with many pro athletes, my income was not only variable, but also destined to be short-lived. At the time, there were no pro skaters over age 25. Plus, the skateboard industry was notorious for its boom-and-bust cycles. But I was too young to care, and the money just kept getting better. As the 1990s neared, I was earning close to $150,000 a year—a ridiculous amount for a pubescent skate rat just out of high school. I socked some of it away, but I also fed my gadget obsession. The local Sharper Image salesmen got hard-ons when I strolled into their store.

Not long after my eighteenth birthday, the skate industry went into a tailspin. The major players like Powell Peralta, Vision, and Santa Cruz crashed hardest, taking hits from all flanks. First, skating simply fell out of fashion—a cultural shift that should have surprised no one since it had happened twice before, in the 1960s and 1970s. Also, the industry was suddenly swarming with small, agile upstarts who were ruthless (and often hilariously brutal) in their determination to take down the big boys. Because they were nimble, the new brands were also better positioned to survive a downturn. On top of all that, the old-guard companies started losing many of their best team riders. Some got recruited away, while others went off to start their own labels.

Note

From:

To: <[email protected]>

Subject: Thank you

I'm a single mom with two sons who are great fans of yours. I thought we couldn't afford your products. I worked very hard to obtain two Birdhouse boards and two Tony Hawk HuckJam helmets. I thank you from the bottom of my heart for making your boards and accessories widely available and affordable.

Powell took a particularly steep dive, partly because it and the Bones Brigade symbolized the clean, parent-approved side of the sport. The newcomers, most notably World Industries, were true anarchists who captured the skate world's attention with their ballsy, uncensored approach. Powell tried to look cool by making videos mocking mainstream exploitation of skateboarding. World ran ads mocking Powell.

To outsiders, the distinction between the old brands and the upstarts was probably hard to discern, since even the biggest skate companies profited by painting themselves, and skateboarding, as counterculture. Powell's graphics featured skeletons, rats, skulls, and snakes—sometimes skulls with snakes. My most popular insignia was a bird skull against an iron cross background, created by Powell's gifted artist, Vernon Courtlandt Johnson. None of it was Sesame Street fare.

But companies like H-Street and World pulled out the stops. They openly ripped off logos from corporate America (Looney Tunes and Burger King, among others). One of World's most infamous skateboard deck graphics had a naked woman in a spread-legged pose—an anatomy lesson. World's founder, Steve Rocco, also got pissed when TransWorld Skateboarding magazine wouldn't publish some of his attack ads, so he created his own skate mag. It was called Big Brother, and it did a good job of covering the hard-core corners of the sport, amid reviews of porn movies and articles like "How to Kill Yourself." (The Big Brother crew would later create the massively successful Jackass TV series and movies.)

By 1991, the skate industry was reeling from uncertainty, civil war, and a declining market. My income from Powell had shrunk to $1,500 a month, and I was struggling to make my mortgage payments. It occurred to me that if I wasn't going to make a living wage from royalties, I might as well take the big step of starting my own company. Also, I figured the industry had no place to go but up, right?

I started talking to a fellow Powell rider, Per Welinder, about teaming up to launch a new brand. Per had a business degree, I had the visibility, and we both had access to seed money. We met secretly for months to draw up a business plan. He would run the day-to-day operations, and I would head up promotions and recruit and manage a team. I refinanced my house, which gave me $40,000 to sink into the business. I also sold my Lexus and bought a Honda Civic. We named the company Birdhouse Projects, and we assembled an amazing team of skaters: Jeremy Klein, Willy Santos, Mike Frazier, Ocean Howell, and Steve Berra.

I was still pretty pessimistic about the future of the skate industry and my own career. I was 24—a geezer. It was time to think about putting away my skateboard and focusing on business.

The early years of Birdhouse were predictably bleak. The skate industry was overloaded with inventory, and we were barely turning a profit. When I took the team on tour, we slept five and six to a room. Occasionally, shops that hired us for demos would tell us after we'd skated that they couldn't afford to pay. One guy offered Chinese food instead of cash. Once, I flew to France for a $300 payday, but an unavoidable ticket change on the way home cost me $100 of that.

I wouldn't have minded the financial stress—in fact, part of me embraced the way the skate recession had weeded out the wannabes—except I suddenly had a new incentive not to go broke: in 1992, my wife Cindy became pregnant with our first son. At home, we pared our budget to the bone. I was given a "Taco Bell allowance" of five bucks a day and I was eating Top Ramen almost daily.

I started seriously weighing options for my post-skateboarding career. My first choice was to become a film editor. I'd already edited some video segments for Powell and all of the early Birdhouse videos, and had enjoyed it, so I borrowed $8,000 from my parents (who couldn't really afford it), and cobbled together an editing system. I actually got paid to edit a few videos, but soon realized I didn't have the contacts, equipment, or resolve to make a living at it.

In early 1994, Birdhouse was on life support, and Per and I discussed pulling the plug. Vert skating (on big halfpipes—my specialty) was dying, so I had stopped competing and was putting more time into the business. I still had a ramp at home, and I was actually skating better than ever (learning new tricks, like heelflip varial liens), but no one was watching. I often skated alone.

As a parting shot to my pro skating career, I asked the Birdhouse art department to use an image of the Titanic on my last signature-model board. It seemed like a good metaphor: the supposedly unsinkable ship, sinking.

Fortunately, my "retirement" didn't last long. For one thing, I never really took to the 9-to-5 desk-job thing. Per and I quickly realized that it was better for the company if I spent more time in the public eye, doing demos and competing, so the company could profit from my high profile. We licensed my old hawk skull graphic from Powell, and began making more products bearing my name.

We got lucky, because 1995 was the year that ESPN debuted something called the Extreme Games (now the X Games) in Rhode Island. I wasn't sure what to expect when the network invited me to compete, since ESPN was all about big-ticket sports like baseball and basketball, but I figured it was worth the risk. The producers went to great lengths to tell the stories of a few select athletes in hopes of giving viewers an emotional attachment to the competitors. That was crucial to the games' success, because mainstream America at that point knew very little about skating or BMX riding. And since I was the best-known skater at the time, ESPN devoted an inordinate amount of airtime to me.

I was stoked to win the vert contest and place second in the street event, but felt embarrassed when I saw the final show. A lot of world-class skaters—friends of mine—never even made it on the air, while I became the face of skateboarding for millions of viewers. Suddenly, people who'd never touched a skateboard were stopping me in airports and restaurants. Sales of my decks skyrocketed in the following years, and the skate industry itself started to benefit from an upswing.

Per and I also owned a distribution company called Blitz, which we used to incubate a variety of small skate brands, such as Baker, Flip, Hook-Ups, SK8MAFIA, The Firm, and Fury. Most of them were the brainchildren of former pros who came in as co-owners.

Those were interesting times. While we helped those brands broaden their distribution and range of products, the owners loved to stir shit up. That was part of the charm, actually: watching misanthropic businessmen compete to see who had the biggest balls when it came to breaking the rules of business. It could also be pretty scary, especially when we lampooned mainstream corporations by repurposing their logos and putting them on skate decks and T-shirts.

Needless to say, we received a lot of terse cease-and-desist letters, but most of those arrived after we'd already ceased and desisted; skateboard graphics rarely last more than one selling season. More often than not, we'd produce and distribute so few of the offending products that the company whose logo got violated would never notice. We did get sued a few times—and usually ended up signing settlement agreements that prohibited me from even talking about those cases. Sorry.

I learned one important lesson through all of this: If you think you or one of your business partners has done something that might get you sued, spend what it takes to hire the best lawyers you can find.

The attorneys didn't always give great advice. A very big candy manufacturer once sued us because it didn't like the way one of our companies had appropriated its logo. Our in-house legal rep suggested the candy maker might drop the suit if we agreed to include coupons for the candy in our own packaging. That one we didn't even try.

Legal potshots also came sometimes from the artists themselves. To keep their designs from getting stale, most small skate companies get their artwork from freelancers. We'd pay the artist a one-time fee for the rights to use a piece of art on everything we manufactured or licensed. The contracts were usually just quick one-sheets—a stupid oversight. When my video game started to do well, an artist came after us because his version of my oft-manipulated hawk skull graphic appeared in the game as one of about 300 different boards that players could choose to ride. We had a contract that said we owned the artwork, we had his canceled check, and we had a copy of his invoice marked "paid." But the guy's lawyer saw deep pockets, and the whole thing turned into a headache.

That was another lesson: These days, we always use an ironclad release for artists' works, and we're diligent about making sure contractors are willing to sign it. If they won't sign, we use someone else.

Videos also triggered their share of lawsuits, especially when it came to using unlicensed music. Very few skate companies could afford to pay for the rights to their favorite songs, but a lot of them just used them anyway—again under the assumption that they were so far under the radar, with such a small audience, that no one would notice. Of course, today, in the age of the Internet, skating bootleggers are way more likely to get busted—especially if their video sections are good enough to go viral.

With the growth of niche television networks, we get approached a lot from TV producers hoping to air clips from old skate videos. But a lot of our best stuff contains poached songs. We end up back in the editing bay, sometimes replacing a great but unaffordable soundtrack with cheesy free music that sounds like it got lifted from a porn movie.

Unlicensed music isn't the only problem. After Birdhouse released its groundbreaking video The End in 1998, one of the producers thought it would be cool to add a bonus "egg" clip to the DVD version. Remember those? You had to scroll around the menu for an egg that would lead you to some hidden video—in this case it was footage of an appearance by me on a national network game show, one of the most popular game shows in the world, a game show that had not given us permission to use its footage. I didn't find out about it until after the DVD shipped to stores.

We had to recall every copy.