Note

WE ARE YOUR BIGGEST FANS! WE EVEN EAT YOUR SERYELL. DON'T RETIRE, YOU THE BEST SKATER EVER. YOU CAN'T JUST QUITE!

FROM AND

In 1998, I got invited to New York to help Froot Loops, the sugary cereal that my skate friends and I used to eat by the case, radicalize its image. Actually, invited isn't quite the right word: A marketing agency paid me to join a team of fellow "extreme" athletes at a big coming-out party where it would be announced that the cereal's mascot, Toucan Sam, was now himself also extreme. (This was before the word got banished to the Island of Misfit Slang.)

The night before the event, I joined BMX hero Dave Mirra and lunatic Olympic ski racer Johnny Moseley at a media-training session with agency execs. They told us that they wanted us to stay in character during press interviews, meaning we were to talk about Toucan Sam as if he were real, and as if he ripped. "You should see that feathered freak's McTwists," that sort of thing. Unfortunately, they failed to caution against inadvertent shout-outs to competitors.

The whole thing would last only a couple of hours, and they were paying $50,000, a lot of money for me at the time. The skateboarding industry was just starting to emerge from the fiscal doldrums of the early 1990s, and I was a young father barely scraping by as a pro skater and co-owner of a struggling skate company. So I figured the money was worth two or three goofy hours.

When we got to Chelsea Piers the next morning, the place was mobbed—with media people and about 100 middle-school kids. The kids, dressed in Froot Loops T-shirts, weren't skaters or even, apparently, fans of the sport; someone had bussed them in, figuring their presence would inject youthful energy to the proceedings.

We did a few interviews, mostly sticking to the script, talking about Toucan Sam as if he were a legitimate action-sports hero. We mused on how he was a true crossover athlete, ripping the streets, snow, and halfpipes. No pads, just fearlessness and feathers.

Note

If I offered you a million dollars, would you endorse my new dildo?

I bet you would.

Chelsea Piers had a big halfpipe at the time, and Dave and I did a demo for the crowd, with Johnny as emcee. One problem: Skateboard and BMX tricks have strange names (stale fish, Madonna, slob air, can-can, tailwhip) and Johnny didn't know any of them. So he improvised, figuring it would be clever to name them after random cereals: "There's Tony with a huge Cheerio!" And "Dave sticks a perfect Grape-Nut." Like that. One problem: Cheerios and Grape-Nuts are made by Froot Loops' competitors. That didn't go over so well with the marketing execs.

I'm not sure what the whole thing did for Toucan Sam's image, but I know for certain it didn't help mine. On the flight back to California, I decided that the Froot Loops episode would be the last time I'd relinquish control to any company that wants to use my name or image to help sell its product. That decision turned out to be a good idea, on many levels.

Skateboarding is a strange profession, probably because it was never supposed to be a profession. Decades after the sport's birth, mainstream America still dismissed it as a fad, a kid's game, a joke. That condescension pushed serious skaters even deeper underground, where they thrived, happy to be seen as counterculture punks. They knew how hard it was to master, and how satisfying; they didn't need affirmation from above. Hard-core skaters were (still are) artists of the purist sort. They do it because they love it, not because they crave recognition or need money.

All of which has placed me in a treacherous middle space—balanced on a tightrope stretched between opposing forces, both of them skeptical. For many years, few adults took my career seriously. Even now, businessmen on airplanes frown when they see me carry a skateboard into first class. At the same time, there will always be a certain segment of skaters who write me off me as a sellout. On the same airplane, they'd give me shit for not riding with them back in coach. But I don't stress about the haters as much as I used to. Most of them have never met me and have no idea how much I love to skate, or how much time I still spend doing it, or how essential it is to my sense of self.

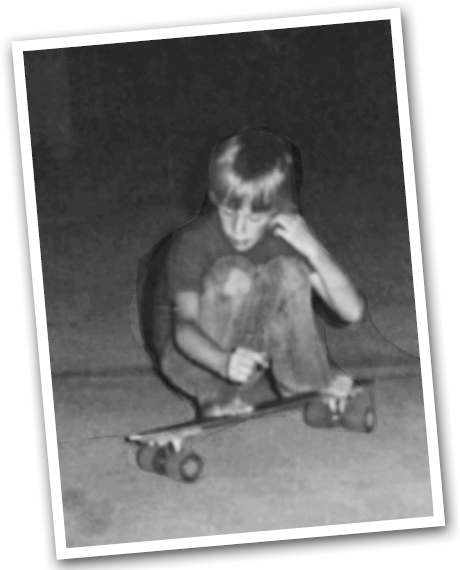

Me, riding on my very first skateboard, given to me by my brother Steve.

At its heart, that's what this book is about, or at least what I hope it's about: how to sell celebrity and promote skateboarding without selling out. For me, it starts and ends with my skateboard, and with the many friends the sport has brought into my life. When I'm torn between business deals, I always seem to pick the one that offers the best chance for my friends and me to skate.

I am acutely aware that I became famous, and make good money, not just because I excelled at my particular sport, but also because I've been extraordinarily lucky. Several times in my professional life I've just happened to be in the right place at the right time. I got into skating when the fad was dead, and turned pro just as it started to benefit from a mid-1980s boom. I ended up on the most famous skate team of the era, Powell Peralta's Bones Brigade, and by the time I was 16, I was making more money than my high school teachers.

When the skateboard industry slipped into a coma in the early 1990s, I still rode my vert ramp almost every day, which enabled me to keep progressing. So when ESPN created the X Games in 1995 and gave skateboarding its first legitimate coast-to-coast TV exposure, there were only a handful of vert skaters still on their game, and I was one of them. The show's producers devoted a disproportionate percentage of airtime to me that first year, and I came away as the "face" of the X Games.

Then, in 1999, the X Games' fifth year, I made a maneuver (the 900: two and a half midair spins) that had eluded me for years. I'd worked long and hard at that trick, but that day also had an element of serendipity: I made it in front of a big TV audience only because skating is one of the few sports in which the people in charge would allow a skater to keep trying a new move, with the cameras rolling, after time had run out.

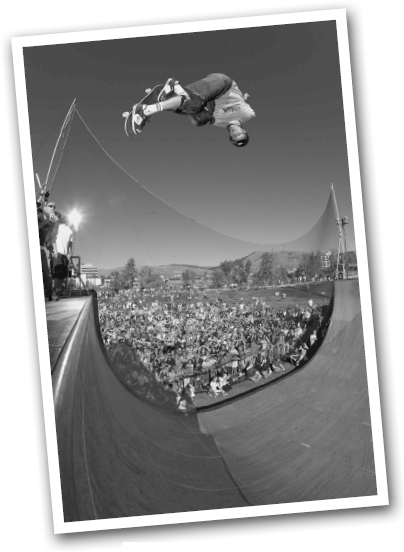

Indy air at one of our Secret Skatepark Tour demos in Missoula, Montana.

That same year, Activision released my first video game, Tony Hawk's Pro Skater, which would go on to be one of the biggest gaming franchises of the decade. The confluence of those three things—the X Games, the 900, the distribution of millions of video games bearing my likeness—elevated my name recognition, especially among young people, to a level I'd never dreamed of. My agent told me around that time that my "Q score" (an authoritative, proprietary poll that measures a celebrity's notoriety and appeal to American consumers) among teens was second only to Michael Jordan's among athletes.

But I really knew the world had gone crazy when I got invited to the 2003 Nickelodeon Kids' Choice Awards, at which the network's viewers named me their favorite male athlete. The other three finalists were Kobe Bryant, Shaquille O'Neal, and Tiger Woods. (A skater beats out Kobe, Shaq, and Tiger? WTF?)

That was when the line from that old Talking Heads' song began repeatedly ringing in my head: "And you may ask yourself, 'Well, how did I get here?' "

There's a lesson in that question, and it's the first one I'd share with those first-class businessmen if any of them were to ever look past my skateboard and ask for advice: Never get cocky about your professional successes, because the good luck that got you there can turn bad fast.

And to any kids who are hoping to learn how they, too, might someday get stink-eye in first class, here are a few other bits of advice:

Once you find your passion, run with it. Ignore what peers or career counselors say.

Don't rebel for rebellion's sake. In fact, rebellion shouldn't even factor into it. If the thing you love and do best is viewed as rebellious, then, yes, embrace your inner Che Guevara. But don't let the cool police dictate your dreams. Think of it this way: If your passion is dismissed as mainstream and dorky, that makes your insurgency all the braver. Do it because you love it, not because you're worried about what others—teachers, friends, that hot emo chick who sits alone by the bike rack at lunch—will think.

Whatever you pick, as long as you truly love it, put in the sweat to get really good at it. That means spending a lot of time at it. Take pride in being defined as obsessive.

Once you've achieved proficiency, take your specialty to a level that fellow specialists can appreciate. Innovate. That's what will set you apart—when you become a pioneer among pioneers.

If all that works and you become successful, stay in touch, and stay humble. Don't get complacent, and absolutely don't get stuck in your ways. Appreciate and acknowledge the genius of your competitors, peers, and future successors. Learn to admire rather than resent.

Become a mentor. Hang with and encourage the people who will inevitably replace you. The higher you move up the corporate high-rise, the more you have to make a conscious effort to spend time in the street. And don't preach. Instead, find the kids who are doing what you did at that age, and have the humility to let them tell you what's going on.

Take it all in, listen to the competing arguments (maximizing profits versus staying true to your art or your roots or whatever), then clear your mind and trust your gut.

Don't be afraid to take risks, but make sure you have good lawyers before you do.

If you get some extra money in your pocket, give back.

Never stop skating.