6.

Get More Inputs

It is now proved beyond doubt that smoking is one of the leading causes of statistics.

Fletcher Knebel

Knowledge is power, if you know it about the right person.

Ethel Watts Mumford

We are here and it is now. Further than that all human knowledge is moonshine.

H. L. Mencken

Over the years I worked with hundreds of creative people in advertising agencies. These were people who got ideas for a living. On demand. Every day.

They came in all shapes and sizes and colors and signs and personalities. One had a doctorate in anthropology, one never got past third grade. They came from close families and from broken homes, from penthouses and from ghettos. I worked with gays and straights, with extroverts and introverts, with flashers, drunkards, suicidals, ex-priests, ex-touts—the list goes on and on.

But they all had two characteristics in common.

First, they were courageous, a subject I will deal with in the next chapter.

Second, they were all extremely curious. They had an almost insatiable curiosity about how things work and where things come from and what makes people tick.

They were curious about pie-making machines and flower drying, about Aztec wedding ceremonies and motorcycle design, about phobias and limes.

They knew things like the name of the horse Napoleon rode at Waterloo (Marengo), how many times egg whites increase in size when whipped(seven), how much a ten-gallon hat holds (three-quarters of a gallon), and the average number of times African elephants defecate every day (sixteen).

Most came by this curiosity naturally. All their lives they had, as one person put it to me, “the need to know.” In some, this need was so overpowering that they came to think of it as a curse instead of a blessing. They were wrong.

For their curiosity was one of the reasons they were able to come up with ideas in the first place. Their curiosity was forcing them to continually accumulate bits of knowledge— “general knowledge about life and events” —the “old elements” that James Webb Young talked about.

And someday they’ll combine those elements with other elements to create an idea. And the more elements they have to combine, the more ideas they can create.

After all, if “a new idea is nothing more nor less than a new combination of old elements,” it stands to reason that the person who knows more old elements is more likely to come up with a new idea than a person who knows fewer old elements.

A copywriter named Jeff Weakley knew the importance of being curious. He sent me the best resume I ever got. It was in the form of a magazine ad.

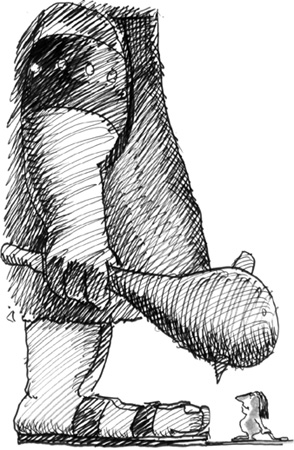

The illustration showed a man’s head piled high with junk—broken pencils, old tires, bottles, and so on.

The headline said: “Invest in a junk pile.”

I read the labels on Vienna Sausage cans. I have worked as a porn projectionist, a disc jockey, and a door-to-door pot-holder salesman. I once read Freud and watched Laverne and Shirley at the same time. The leader of the King family was named Elmer. I have studied and worked with film, television, radio, and photography. I play sports, speak Spanish, and know the names of all the teeth in my mouth. I have read a lot of books and seen a lot of movies. I know of a disease that causes men to eat dirt, ice, and laundry starch. Most importantly, I know something about Egyptian burial customs and dual-in-line-package 14-pin quad two-input NANS gates.

I’ve always been like that. I’ve created in my mind this giant junk pile of seemingly worthless information.

And then I discovered advertising. The junk pile became a treasure overnight.

As I am at the earliest stages of my advertising career, I am offering you the opportunity to invest in this junk pile. For a very good price.

If you’re interested in seeing the rest of my collection, please call.

Thank you.

If you do not have a natural curiosity like Jeff’s that forces you to accumulate bits of knowledge, you must force yourself.

Every day. Deliberately.

Every day since he was twelve, Ray Bradbury once told me, he read at least one short story, one essay, and one poem. Every day. He said he never knows when something he read twenty years ago will “collide” (his word) with something he read yesterday to produce an idea for a story.

When was the last time you read a short story or an essay or a poem? Is it any wonder Ray Bradbury comes up with more story ideas than you do?

Here are two ways to force yourself to get more old elements:

1. Get Out of Your Rut

Of course you’re in a rut. Admit it.

Why do you think you do the same things the same way in the same order every morning when you wake up? Or have the same thing for breakfast every day? Or go to work the same way every day? Or always read the same parts of the newspaper? Or always buy the same things at the supermarket? Or always watch the same TV programs? Or eat the way you eat, or dress the way you dress, or think the way you think, or, or, or?

It’s because you’re in a rut.

And because you’re in a rut, every day your five senses are recording the same things they recorded yesterday—the same sights, the same feelings, the same smells, the same sounds, the same tastes.

Oh, sure, different things creep in every now and then. You can’t help it. Not even a deaf, blind hermit can keep out new sensations.

But they creep in, in spite of what you’re doing not because of what you’re doing.

And if you just stay in your rut and let things creep in naturally, you’ll never pile up the kind of varied and extensive database you need to form new ideas.

There’s a huge, fascinating, exploding world of information out there—in any direction you care to look.

But you must look. And the sooner you do the sooner you’ll become aware of “old elements” you didn’t even know existed.

As Jerry Della Femina says: “Creativity is about making a lot of quick connections—about the things you know, the things you’ve seen. The more you’ve done, the easier it is to make that jump.”

Perhaps that’s why André Gide was so creative. Legend has it that he tried to read at least one book every month about a subject in which he had no interest. Have you ever done that? Do it. At least once.

Listen to a radio station you’ve never listened to before.

Study Latin.

Order something at a restaurant without knowing what it is exactly.

Read the want ads. Read Marianne Moore and Allen Ginsberg and Ted Kooser. Read a children’s book. Reread Death of a Salesman. Read a magazine you’ve never heard of.

Check out something on the Internet you think you’ll dislike. See a play or a movie you think you’ll dislike. Rent a video you’ve never heard of.

Touch the bark of three different trees in your neighborhood. Learn to tell which is which simply by how it feels. Learn to tell which is which simply by how it smells.

Go to lunch with someone different.

Listen intently to music you don’t like.

Ride the bus for a week.

Learn to read music. Learn sign language. Learn to make quenelles. Learn to tie knots.

Take up watercolor painting.

Study Greek. Or Chinese. Or English.

Visit a store, a gallery, a museum, a restaurant, a market, a mall, a building, a place you’ve never visited before.

Of course I’m not saying to do all of these things.

But please, today, do something. Something different, something that will get you off dead center, something that will start you in a different direction, something that will get you out of your rut.

“If you want to be creative,” Louis L’Amour said, “go where your questions lead you. Do things. Have a wide variety of experiences.”

A writer friend of mine in Los Angeles lived about ten miles from his office. It was a straight shot, right down Wilshire Boulevard from Westwood to downtown. But he never once took Wilshire. Indeed, every weekday morning for nine years he drove to work a different way. Never, he claims, did he go the same way twice. “Admittedly, there were times when I had to do some pretty crazy things to keep from taking the same route,” he remembers. “I had to drive down alleys, and wander through residential areas, and get on freeways going away from where I wanted to go. But I never repeated myself. And I bet I saw more of Los Angeles in those nine years than most people will see in their lifetimes.”

In what way are you richer than my friend because you go to work the same way every day?

Every day he saw something he never saw before. Every day you see the same things you saw yesterday. He was constantly seeing new things. You are constantly seeing the same old things.

Tomorrow go to work a different way. And a different way the next day. And the next. Forever.

2. Learn How to See

Back before the Second World War my dad and mom and I used to drive from Evanston, Illinois, to my mom’s parents’ house in Danville, Illinois. We went every month or so. It was about a two- or three-hour trip in those days. Sometimes we played a game called “White Horse” on the way. It was a simple game really—the first person to spot a white horse by the side of the road or way back off in some pasture said, “White Horse,” and at the end of the trip the one who spotted the most white horses first won the game.

Now the interesting thing I remember about that game is that when we played it we saw all sorts of white horses. But when we didn’t play the game we hardly saw any at all.

Why?

It wasn’t because there were all sorts of white horses around when we were playing and only a couple around when we weren’t.

It was because when we were looking for those white horses we saw them; when we weren’t, we didn’t.

The same thing happens when you just buy a car, or even if you’re just thinking about buying a car. All of a sudden you start seeing cars like that all over the place.

They were always there before. You just didn’t see them because you weren’t looking for them. But as soon as you got interested in that particular car you started—consciously or not—looking for them. And voilà, there they were.

And what’s true about white horses and cars is true about everything.

For you see everything that comes in contact with your eyes.

You see every car that you passed on the way to work this morning. And every car that passed you. And every driver in every car that you passed or that passed you.

You see every tree and bush and patch of grass you passed too. And every telephone pole, every gas station, every building, every traffic light, every person, every street lamp, every mailbox, every everything.

Then how come you can recall only a fraction of what you see?

It’s because you weren’t really seeing. You were simply looking. Not looking for, just looking. Looking requires no effort at all. It’s as easy as breathing. Seeing is different; it requires effort. And commitment.

But hear this: Once you get the hang of it, seeing becomes almost as natural as looking.

Let me tell you a couple of stories:

Evanston, where I grew up, was dry. If you wanted to get a drink you had to go to Skokie or down to Howard Street, the street that divided Evanston from Chicago. My friend Bob Bean and I used to go to Howard Street a lot. There was really nothing else for us to do, for at that time we were both short and fat and covered with pimples and couldn’t get dates to save our souls; and there were a lot of bars on Howard Street that would serve you beer even if you weren’t quite twenty-one. Or even not quite nineteen, for that matter.

One night we were sitting at a bar and Bob said, “Put your head down for a minute.” I did, and then he said, “How many cash registers are there behind the bar?”

“One,” I said.

“Three,” he said. “Keep your head down. Now how many people besides us are in this bar?”

“Twelve?” I said.

“Eight,” he said.

And that started us on a game that we played, off and on, for more than three years.

We’d walk into a bar, order a beer, and spend exactly ten minutes looking around, studying and memorizing every detail we could. After ten minutes we’d each put our heads down and start asking each other questions.

“How many chairs are there in here?” “How many windows?” “How many steps from the door to the bar?” “What color are the bartender’s eyes?” “What’s the ceiling like?”

After a couple of months we got so good at it, it was hard for either of us to ask a question the other couldn’t answer.

“How many bottles are there behind the bar?” “Describe every picture and sign on the walls.” “What was rung up on each cash register when we walked in?”

By the time we stopped playing, there was nothing we didn’t know.

“Tell me the name of every bottle that’s behind the bar.” “Now, how full is each bottle? Half full? A quarter full? Three-quarters full?”

Really, we could do it.

“How many slats are there in those blinds that cover the front window?” “Describe in detail every person here.” “How many glasses and bottles are there on each table?”

We had discovered the magic of seeing.

Years later I was working with another friend, Hal Silverman. Hal is an artist, one of those irritating people who can draw what he sees. He was drawing a chair. “Boy,” I said, “that looks great—just like a chair. I wish I could do that.”

“Do what?” he said.

“Draw something that looks like what it is.”

“Why can’t you?”

“I don’t know; I just can’t. If I tried to draw that chair it’d probably come out looking something like a chicken.”

“You got something the matter with you?”

“What d’you mean?” I said.

“Can you print numbers and the alphabet? Can you write your name?”

“Of course.”

“You got Saint Vitus’ dance or arthritis or dyslexia or something?”

“Your eyes are OK?”

“Sure.”

“Then why can’t you draw what you see?”

“I don’t know; I just can’t.”

Hal shook his head. “If there’s nothing physical that prevents you from drawing that chair, it must be something mental that prevents you from doing it.”

“Huh?”

“You’ve got a good command of your motor functions, your eyes are fine, you’re not in pain, so the reason you can’t draw this chair must be because you’re not seeing the chair.”

“Of course I can see the chair.”

“Agreed. You can, but you’re not.”

“What d’you mean, I’m not?”

“If you really saw it, you could draw it. Here,” he said, picking up the chair and handing it to me, “look at it for ten minutes. Study it. Take it apart in your mind. Then put it back together. Study its design, its shape, its form, its size, its materials, its construction, its colors. Look at how each piece of wood joins with every other piece. Notice how these pieces here are curved inward and these are curved outward. Concentrate. Take mental notes. Note that the back is longer than the legs, that the seat is wider than the back, that the front of the seat is wider than the back of the seat, that the legs splay outward slightly, that the back rest is bent backward. Count the cross members, notice how the turning on the legs is different from the turning on the arms. Look at it upside down, sideways, backward. Look at it. Work at it. If you do, you’ll probably learn more about that chair in the next ten minutes than you have about any chair in your lifetime. And when you’re through, you’ll be able to draw something that actually looks like the thing you’ve learned about.”

I did what he said. And he was right. After ten minutes, I was able to draw something that looked like a chair. Granted, the legs had a decided chickenlike quality to them, but still—it actually looked like a chair.

It’s hardly necessary to point out that if you see things the way Bob Bean and Hal Silverman do, you’ll be able to remember more of what you see.

I’m not saying that you’ll remember everything you see. Nobody can do that. Nor am I saying you’ll ever be as good as Hal Silverman is at drawing things. Some people are simply better at those kinds of things than other people.

But I am saying that by working at it you can see more and remember more of what you see than you ever dreamed you could. You can remember more about the people you meet and the places you go and the things you read.

And the more things you remember, the more things you’ll have to combine in order to form new ideas.

But you must work at it. Every day.

Tomorrow morning on your way to work, or on your first coffee break, buy yourself a notebook. Not a loose-leaf notebook. Buy a ledger—something with a sense of permanence to it. Then every day write in it something that you’ve seen. Every day. It doesn’t make any difference what you see; only that you see something and record it. (If you also want to write what you think about what you see, feel free. After all, that’s what Thomas Wolfe and hundreds of other writers did and do.)

When your ledger is full, sit down and read it. Then start filling up another one. And another one. And another one.

For the rest of your life.