5.

Rejoíce ín Faílure

It is not enough to succeed. Others must fail.

Gore Vidal

The theory seems to be that so long as a man is a failure he is one of God’s chillun, but that as soon as he has any luck he owes it to the Devil.

H. L. Mencken

I picture my epitaph: “Here lies Paul Newman, who died a failure because his eyes turned brown.”

Paul Newman

To swear off making mistakes is easy. All you have to do is swear off having ideas.

Leo Burnett

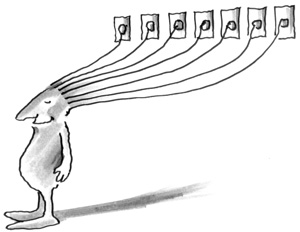

Here are five reasons why you should make failure a friend:

1. The only way to know that you’ve gone far enough is to go too far. And going too far is called failing.

But if you don’t go far enough in searching for an idea—if you don’t, in other words, fail—you can’t be sure you’ve got the best idea.

So never fear failure or try to avoid it. Embrace it. Rejoice in it. It’s a sign that you’ve gone far enough.

Race car drivers know this in their bones. They even have a saying about it:

“The one sure way to find out if you’re going fast enough is to crash.”

Cooks know it too.

Nearly everything they make has an “Oops, we’ve gone too far” point to it.

And the only way they can learn where that point is, is to go past it.

So they learn not to burn rye toast or Porterhouse steaks, not to oversauté chicken breasts or garlic or scallops, not to overmix whipping cream, or oversteam broccoli, or overwhip egg whites, not to overbake pork roasts or cakes or soufflés, not to . . .

And the only way they can learn them irrevocably is by failing.

Emulate race car drivers and cooks.

Go too fast. Go too far. Let your mind wander into dangerous ground, into silliness, absurdity, stupidity, impossibility. Surprise your teachers. Astound your friends. Embarrass your parents. Thumb your nose at the laws of nature and science and common sense.

Crash.

Burn.

2. Ralph Price, an advertising agency art director I used to work with, says the same thing about failure. “You don’t know if you’ve succeeded until you fail,” he used to say. But he meant something slightly different.

He meant that many times you don’t know if an idea is any good until you have other ideas to compare it to.

That’s why writers and art directors in advertising agencies come up with many ideas on every project they’re working on.

I suggest you do the same thing on the problem you’re working on. Once you come up with an idea that seems to work, put it aside. It won’t go anywhere.

Then come up with another idea. And then another one. And then . . .

For as I explain in chapter 13, there’s always another one. Always.

3. “I have not failed,” Thomas Edison said. “I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.”

Emulate Edison. Put a positive spin on things when they don’t work out. Believe that every failure brings you one step closer to success. It will prevent you, as it did Edison, from becoming discouraged. More, it will urge you on.

4. When you fail, it changes your mind set, the way you look at life.

Failing makes you fearless. Failing sets you free.

Perhaps Jerry Della Femina, the famous advertising man, said it best:

Failure is the mother of all creativity. My advice to anybody who wants to be creative is to get into something that will fail. I’ve failed at a lot of things in my life and I hope to fail at a lot more. Most people are afraid to fail, but once you’ve done it you find out it’s not that terrible. There’s a sense of freedom that you get from taking chances.

A friend of mine who was opening an office in Los Angeles for a major national advertising agency also knew this about failure. He was deluged with hundreds of applications.

“What kind of people are you looking to hire?” I asked him.

“The usual. Writers, art directors, account people, media, research—you know.”

“But how do you choose, for example, one good media person from another?”

“I have to like them. If I don’t like them, I won’t hire them no matter how well qualified they are.”

“What else?”

“I must confess I’m partial to people who have failed.”

“What?”

“People who have failed. They know that failure’s never permanent. Too often, people who haven’t failed at anything think that failure’s a disaster, and so they’re afraid to go to the edge of what’s possible. They’re afraid to take chances. And because they’ve never failed, they think they know it all. I hate know-it-alls. Besides, you’re always getting rejected in this business. That’s just the way it is. I want people who I know will spring back.”

The space program, so the story goes, felt this way too.

In selecting astronauts, legend has it that NASA looked for some evidence of failure in the resumes of the recruits. They knew that at some point in a space journey, the unexpected might happen—things might break down, fail, not go as planned.

They wanted people who would not be unnerved by such a situation; people who had experienced failure before and had learned from it, become wiser and stronger from it; people who knew that failure is nothing but a temporary setback, a prelude to success, a door being opened, as well as a door being closed.

So don’t hide your failures or be ashamed of them.

Wear them with pride. Revel in them.

5. Of course what I’ve been talking about are failures where you know things aren’t working—crash-and-burn failures, failures that point you in another direction, failures that teach you something.

Every now and then, however, you know in your heart that your idea is a good one, that your solution will work if given the chance, that what you’ve done is right.

When that happens, use the failure as a motivation to keep trying.

The “I’ll show them!” drive is a powerful vehicle. Ride it.

There are hundreds of stories about how this kind of stubborn refusal to accept failure eventually led to success.

Chester F. Carlson, inventor of the Xerox machine, spent seventeen years trying to get companies interested in his photocopying device.

Bette Nesmith Graham made her Liquid Paper (then called “Mistake Out”) in her kitchen for a decade before it started to sell big.

Alfred Mosher Butts aggressively marketed his Scrabble game for four years before it caught on.

It took James Russell twenty years to convince the music industry to adopt his “digital music” invention.

Catch 22 was turned down by 23 publishers; Dr. Seuss by 24; Sister Carrie by 28; Chicken Soup for the Soul by 33; Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by 121.

Finally, if you’ll allow me—a personal story of stubbornness:

Over a period of two years, I sent the original manuscript for this book to 74 publishers. Every time I got a rejection, I sent it out to a couple more publishers. The 44th one, Steven Piersanti of Berrett-Koehler, decided to publish it four months after I sent it to him. (While he was deciding, I sent it to 30 other publishers.)

Had I given up after getting 43 rejections, there would not have been a first edition of How to Get Ideas, a book that has sold nearly 100,000 copies and been translated into fifteen languages.

Nor would you be reading this second edition now.