Management used to be much simpler: bosses bossed and workers worked. Managers used their heads and workers used their hands. Thinking and doing were separate activities. Those were good times for managers, but bad times for workers.

Somewhere, it all started to go horribly wrong for managers. Workers slowly acquired more rights while managers lost their perks; workers got shorter working hours, managers had to work even longer hours. And while workers got the benefits of the 24/7 economy, managers got the stress of being constantly shackled to the electronic fetters of email, texts and phone.

Management has become harder. It has also become more ambiguous. Think for a moment about the rules of success and survival in your organisation. You can look in vain at the formal evaluation criteria to find the real rules of survival and success:

- How much risk should I take if I want to survive, and how much should I take if I want to succeed?

- What are the right projects and people to work with?

- When do I stand up and fight and when do I concede gracefully?

- How do things actually get done in this place?

- What are the bear traps to avoid?

- How do I manage my boss?

There is no policy manual to tell you this and no training programme to help you. Bosses do not come with a user guide or guarantee. You are on your own when it comes to the important rules. Policies deal only with the minor rules.

In practice, we discover the rules of survival and success by comparing people who succeed and survive to those who struggle. And then we work out why they succeed, survive or struggle. Take a look and see who succeeds where you work. Hopefully, people who have a track record of success are among the winners. But in flat organisations, knowing who was really responsible for what can be a challenge.

Most evaluation systems look for two sorts of characteristics, which are called many different things.

Traditionally, managers (who had the brains) were meant to be smarter than the workers (who had the hands). A good IQ, or intelligence quotient, helped. Many assessment systems still assess IQ. Entry into many business schools is still based on IQ, in the form of the GMAT (a common test). In companies, IQ is often presented as having problem-solving skills, analytical capability, business judgement and insight.

Being a brain on a stick is not enough – managing is about making things happen through other people. Many smart people with a high IQ are too clever to make anything happen. Most companies also look for good interpersonal skills, or good EQ (emotional quotient). This will be dressed up as teamwork, adaptability, interpersonal effectiveness, charisma, ability to motivate and similar code words for EQ.

Now use the criteria of IQ and EQ to see who succeeds and fails. Look around your workplace. You should find quite a few managers with good IQ and EQ: smart (IQ) and nice (EQ) managers exist, despite the media stereotypes. But you will also find plenty of smart and nice people who lead lives of quiet under-achievement in the backwaters of the organisation: liked by all and going nowhere fast. Meanwhile, there are plenty of successful managers who are not so smart and not so nice who rise to the top, using the smart and nice managers as doormats on their way to the top.

Something is missing. It helps to have good IQ and EQ, but it is not enough. Another hurdle has come into place for managers to jump. As ever, things are getting tougher, not easier, for managers.

The new hurdle is about political savvy or PQ – political quotient. PQ is partly about knowing how to acquire power. Even more, it involves knowing how to use power to make things happen. This places it at the heart of management, which is about making things happen through other people.

Of course, all managers have always needed some degree of PQ. But in the command and control hierarchies of the past, it did not require much PQ to make things happen. An order was normally enough. In today’s world of flat and matrix organisations, power is more diffused and ambiguous. If management used to be about making things happen through other people, now it is about making things happen through people you may not control and may not even like. If there is a revolution in management, it is not about technology: the technology revolution has been with us for at least two hundred years. The management revolution is about how you have to make things happen in a far more complicated, difficult and ambiguous world than before.

Making things happen means that you have to build alliances, seek help and support and reach out beyond your formal areas of authority. Many of the resources you need may not even exist in your own organisation. Managers need PQ more than ever before to achieve their ends.

Successful managers are three dimensional: they have IQ, EQ and PQ. Each of these capabilities is a series of skills which can be learned. You do not have to be academically smart to be a good manager: many academic institutions are full of smart people and bad management. How to Manage shows how you can be managerially smart without having to be academically smart. Similarly, EQ and PQ represent skills that all managers can learn.

How to Manage lays out the managerial skills behind IQ, EQ and PQ. It shows how you can build your capabilities to survive and succeed in the management revolution. It cuts through the noise of the daily management struggle and the babble of management theory to focus on the critical skills and interventions managers need. It shows what you have to do and how you have to do it in a world that is tougher and more complex than ever.

As a first step in understanding the revolution, we will look at how the revolution came about and where it is taking us.

Rational management

As long as there has been civilisation, there has been management – even if no one realised it at the time. Management started to evolve as a discipline in its own right with the Industrial Revolution: large-scale operations required large-scale organisation. Early management organisation and strategy was based on military strategy and organisation: classic command and control.

Slowly, industrial management evolved away from military management. Just as Newton discovered the laws of physics, so managers went in search of the elusive formula for business and management success. It is a formula that academics still search for, although successful entrepreneurs do not need a theory to succeed. Scientific Management was an early attempt to bottle success.

The high priest of Scientific Management was Frederick Taylor, who wrote The Principles of Scientific Management in 1911. Below is a flavour of his approach:

One of the very first requirements for a man who is fit to handle pig iron as a regular occupation is that he shall be so stupid and so phlegmatic that he more nearly resembles in his mental make-up the ox than any other type. The man who is mentally alert and intelligent is for this very reason entirely unsuited to what would, for him, be the grinding monotony of work of this character.

Taylor took a dim view of workers as a whole, believing that they would work as little as they could without getting punished. But his work was not based on pure opinion: it was also supported by close observation. This led to some ideas that were revolutionary at the time:

- Workers were made to rest regularly, even if they did not want to, because it made them more productive.

- Different types of people should be given different types of job because they would be more productive in the right jobs.

- Production lines, which break up complicated jobs such as assembling cars or fast food, maximise productivity and minimise the skills and costs of the employees required.

These lessons are applied still today.

The world of scientific, or rational, management was brought to life by Henry Ford’s introduction of the moving production line for making cars. Between 1908 and 1913 he perfected the concept and started to produce the Model T, which he called with great marketing aplomb ‘a motor car for the great multitude’. Some 15 million Model Ts had rolled off his assembly lines by 1927, bringing cars to the masses and sweeping away the cottage industry of craftsmen custom-building cars at great expense.

Rational management is alive and kicking, even in the twenty-first century. It still exists on car assembly lines, in fast-food restaurants and in call centres where hapless operatives work to scripts that make them little more than machines. Many companies have taken the next logical step and removed the humans completely so that customers are left talking to computers.

Emotional management

The world of rational, scientific management was relatively simple: it was based on observation and cold calculation.

Then it all started becoming complicated for managers.

Somewhere along the line, someone discovered that workers were not mere units of production, and possibly even of consumption. They had hopes, fears, feelings and even the occasional thought. They were, in fact, human beings. This really confused matters for managers. They not only had to handle problems, they also had to handle people.

Over time, people became harder to handle. Workers became better educated and better skilled: they could now contribute more, but they also expected more. They became wealthier and more independent. The days of the one-factory town were numbered: there were alternative forms of employment. The Welfare State emerged for those who could not or would not find employment. Employers lost their coercive power. They could no longer demand loyalty; they had to earn it. Slowly, the workplace was moving from a culture of compliance to a culture of commitment.

The challenge for management was to produce the high-commitment workplace, engaging people’s hopes instead of simply playing on their fears. 84 years after Frederick Taylor published his book, Daniel Goleman appeared in 1995 as the high priest of the new world of emotional management with Emotional Intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. He was, in effect, popularising thinking which had been emerging for decades. As early as 1920, E L Thorndike of Columbia University had been writing about ‘social intelligence’. For a long time, thinkers had realised that smart thinking (high IQ) was not correlated directly with life success: other things seemed to be important.

In the workplace, experiments with emotional intelligence (EQ, not IQ) had long been taking place. The Japanese, in particular, made great strides in involving workers properly, even on car production lines, through new movements such as kaizen (continuous improvement). Perhaps, ironically, they took much of their inspiration from an American, W Edwards Deming. Deming’s ideas gained acceptance in America only when the Japanese started to decimate the American auto industry with the help of his ideas.

By the end of the twentieth century, the manager’s job had become far more complicated than it had been at the end of the nineteenth century. Twentieth-century managers needed to be just as smart as their predecessors of a hundred years before. They needed EQ (emotional quotient) to deal with people as much as they needed IQ to deal with problems. Most managers found that they could be good at one or the other: few managers have genuinely good IQ and EQ. The performance bar for effective management had been raised dramatically.

Political management

Two-dimensional managers cannot exist, except as cartoon characters. Real people and real managers exist in three dimensions. The concepts of high IQ and EQ are good, but they are not sufficient to explain the success or otherwise of different sorts of managers. Something is missing.

The first clue to finding the missing piece of the puzzle is to recognise that organisations are set up for conflict. This is a surprise to many academics who think that organisations are set up for collaboration. In reality, managers have to fight for a limited pot of their organisation’s time, money and budget. There are always more needs than there are resources. Internal conflict is the way that these priorities are decided. Marketing, operations, service, HR, and the different products and regions all slug it out to get their fair share of the cake.

For many managers, the real competition is not in the marketplace but sitting at a hot desk nearby, fighting for the same promotion and the same bonus pool.

The second clue to the missing piece of the puzzle is to look at who wins and loses in these corporate contests for budget, time, pay and promotion. If we are to believe the high IQ and EQ theory, then all the smart and nice people should get to the top. Casual observation of most organisations shows that this is not true. Smart and nice people do not always win: many disappear off the corporate radar screen entirely or live as quiet under-achievers. On the other side of the coin, most of us have experienced senior managers who are neither bright nor pleasant, and yet they rise mysteriously into positions of power and prominence.

Clearly, there is something more than IQ and EQ.

A short chat around the water cooler often is enough to discover what is missing. Conversation can often turn to who is going up or down the corporate escalator, who is in and out, who is doing what to whom, what the big emerging opportunities are, and what the emerging Death Star projects are and how to avoid them. Such conversations show that humans are not only social animals: we are also political animals.

Politics is unavoidable in any organisation. Nor is politics new. Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar is politics dramatised. Machiavelli’s The Prince is the Renaissance guide to successful political management. Politics has always been there, but it has been seen as a slightly dirty topic, not fit for academic analysis or for corporate training programmes. Caesar’s murder shows what happens when you do not read the politics well. When anyone says, as Brutus said to Caesar, ‘I’m right behind you’, alert managers realise that this means they are about to be stabbed in the back.

For some, politics is a malign force and it is about back-stabbing. For more effective managers, it is a benign force. PQ is the art of making the organisation work with you and for you. It is how you make things happen through parts of the organisation you do not control. That puts it at the heart of modern management, where managers find that they do not control all the resources they need for success.

IQ and EQ are not sufficient to deal with such politics. There is a constant contest for control and for power. The endless need for change is not just about changing individuals: it is about changing the power balance in the organisation. These are deeply political acts for which the successful manager needs deep political and organisational skills.

The importance of politics is growing and will keep on growing, because the nature of management itself is changing. Over the last 20 years there has been a slow-motion revolution in management. From day to day you cannot see the revolution, unless it sweeps you away in a blitz of outsourcing, offshoring and re-engineering. But over 20 years, it is clear that the old order is vanishing and a new order is emerging.

The old order was based on command and control. The job of a manager was to transmit orders down the command chain, and to send messages back up it. Effective managers made things happen through the people they controlled.

Because managers no longer control all the resources they need in order to make things happen, that changes everything. Now you have to make things happen through people you do not control, and may not even like. Traditional command and control just does not work in this world: you cannot simply order your peers, colleagues, customers and bosses to do what you say. You have to learn a whole new set of skills around influencing, persuading, building networks of trust, securing resources and teams and making things happen without formal power: that is the real world of PQ.

Clearly, some managers and some organisations are still in the old world of command and control. But the tide is moving against those ways of working, even in the public sector. If you want to thrive, make sure you are on the right side of the revolution. Acquire the PQ skills that will let you flourish in a world that is becoming more complicated, more ambiguous and, yet, has more opportunity than ever.

Management quotient

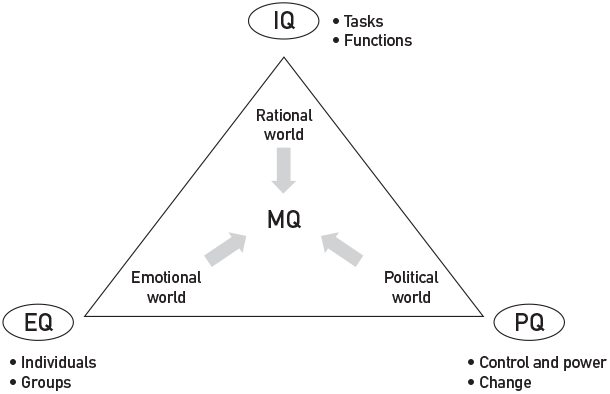

Perhaps it is now time to recognise that real managers are three-dimensional. In addition to high IQ and EQ, they need high PQ: political quotient. If there is such a thing as a success formula in management, it might be summarised as:

MQ = IQ + EQ + PQ

MQ is your management quotient. To increase your MQ, you need to build up IQ, EQ and PQ (see Figure 1.1 below). The success formula is easy to state, hard to achieve.

MQ is about management practice, not management theory. How to Manage shows how you can use MQ as a simple framework to:

- assess your own management potential

- assess team members and help them identify how they can improve

- identify and build the core skills you need to succeed

- identify the rules of survival and success in your organisation.

Components of MQ

There are countless ways to apply the MQ formula and to succeed or to fail. Each person develops and applies IQ, EQ and PQ in different ways to suit different situations. Your management style is as unique as your DNA. How to Manage does not provide a formula for producing managerial clones. You deserve better than that. It provides a set of frameworks and tools to help you understand and deal with typical management challenges.

Some people treat frameworks as prisons: they mindlessly apply the same formula to every situation. Others use frameworks as scaffolding around which they can build their own unique management style. They adapt the tools to their particular circumstances. How to Manage helps you adapt the tools and frameworks by showing not just the theory, but also the reality of what works and, more importantly, what does not work. We all learn from experience, both positive and negative. This book crams thousands of years of cumulative experience from practising managers into a few pages. Use How to Manage well and you will be able to build your MQ to succeed on your own terms.