How to Manage Alliances Strategically

Why do so many strategic alliances underperform — and what can companies do about it?

Since its initial public offering in 2010, the electric car manufacturer Tesla Motors Inc. has had some substantial successes. For example, in the summer of 2016, the company boasted a market capitalization of around $30 billion, an appreciation of more than 800% over its initial public offering price in 2010. Tesla’s leading executives (including cofounder and CEO Elon Musk, chief designer Franz von Holzhausen, and cofounder and chief technical officer J.B. Straubel) deserve much of the credit for this. However, it’s also important to recognize the role played by Tesla’s strategy of creating alliances with larger, more established companies. Two key strategic alliances in particular — one with Daimler AG and the other with Toyota Motor Corp. — were crucial to Tesla’s early success. The Daimler partnership provided a much-needed cash injection; the Toyota partnership gave Tesla access to a world-class automobile manufacturing facility located near its headquarters in Palo Alto, California.

Initially, Tesla, which began selling its all-electric Roadster model in 2008, had neither a market nor legitimacy. Moreover, it was plagued with both thorny technical problems and cost overruns. Yet it managed to overcome these early challenges, in part by turning prospective rivals into alliance partners. In 2009, the year before its IPO, Tesla worked out the alliance with Daimler, whose roots in automobile engineering extend back to the early days of the automobile powered by an internal combustion engine about 130 years ago. The deal provided Tesla with access to superior engineering expertise and a cash infusion of $50 million, helping to save the company from potential bankruptcy.

The alliance with Toyota, signed the following year, brought other benefits. It enabled Tesla to buy the former New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc. (NUMMI) factory in Fremont, California — created as a joint venture between Toyota and General Motors Corp. in 1984 — and to learn large-scale, high-quality manufacturing from a pioneer of lean manufacturing. As it happened, the NUMMI plant was the only remaining large-scale car manufacturing plant in California, and some 25 miles from Tesla’s Palo Alto headquarters. Without this factory, Tesla would not have been able to initiate production planning for its recently announced Model 3, which received more than 350,000 preorders within three months of its announcement.1

In 2014, Tesla Motors signed another strategic alliance — this one with Osaka, Japan-based Panasonic Corp., the consumer electronics company and a world leader in battery technology. As Tesla tries to position itself in the business of sustainable and decentralized energy, the relationship with Panasonic is significant. The two companies are jointly investing in a new $5 billion lithium-ion battery plant in Nevada. Tesla’s ability to attract and manage leading companies in the automotive and other key industries as strategic alliance partners is an important part of its formula for success.

The decisions by Daimler, Toyota, and Panasonic to collaborate with Tesla highlight that individual companies may not need to own all of the resources, skills, and knowledge necessary to undertake key strategic growth initiatives. When conditions are uncertain and the stakes are high, partnerships can be an attractive alternative to going it alone or to mergers and acquisitions.2 Accordingly, many companies now maintain alliance portfolios. As a result, executives must manage multiple alliances with diverse partners across the globe simultaneously.3 However, the skills required to develop and manage alliances are still not well understood. Prescriptions for how to achieve effective alliance management are frequently too condensed, piecemeal, and static — and don’t pay adequate attention to the strategic element. In this article, we attempt to address these shortcomings by offering an integrative and holistic framework of alliance management along with practical guidance.

Taking a Strategic Approach

The Tesla example illustrates the potential benefits of a carefully crafted and well-executed alliance strategy. Although strategic alliances are often viewed as a critical tool for pursuing growth opportunities, survey data suggests that roughly one half of all alliance portfolios underperform.4 These assessments of alliance performance are subjective; however, it is fair to say that many alliances fail to live up to expectations. Why? In theory, growth in the number of alliances should mean that companies are able to develop alliance capabilities through learning-by-doing.

Our research on the factors driving alliance performance, however, shows that companies move down the learning curve at different rates.5 (See “About the Research.”) Smaller companies may have advantages in this relative to larger partners because they are usually less complex internally and have stronger incentives to learn. We found that the benefits of alliance experience do not come automatically but depend on the extent to which the organization can actively capture and leverage its experience (for instance, one partner may be able to draw additional benefits from an alliance, while the other may continue to make the same old mistakes).6 Hence, a company’s alliance portfolio — the combination of all of its alliances — requires a holistic and strategic approach. Tesla, for instance, doesn’t view its alliances as individual deals but as part of an overall strategy to establish a new standard in automotive technology and, along the way, to gain a competitive advantage.7

About the Research

We conducted several studies over a period of several years to understand how companies learn to manage alliances. In the first study, we took an in-depth look at nearly 300 R&D alliance projects between large pharmaceutical companies and smaller biotech partners over two decades. We focused on two types of learning-by-doing: general alliance experience (obtained from the breadth of a company’s alliance activity across different partners in its portfolio) and partner-specific alliance experience (obtained from allying repeatedly with the same partner over time). Based on the experience curve, we predicted that the relationship between alliance experience and alliance performance would be positive but that there would be diminishing marginal returns to the subsequent partnerships. This implies that although additional incremental learning can be obtained from entering subsequent alliances, the absolute learning contribution from each additional alliance declines.

Some interesting and unexpected results emerged from our empirical study. First, only the general alliance experience of the biotech partner mattered in subsequent R&D project performance. As expected, this relationship exhibited diminishing marginal returns. Second, counter to our prediction, partner-specific alliance experience actually had a negative effect on subsequent R&D project performance; performance diminished over subsequent alliances with the same partner. This shows how difficult it is for large companies to leverage their prior experience.

In another study of more than 2,200 R&D alliances by 325 global biotechnology firms, we empirically investigated the effect of alliance-specific and firm-level factors on a company’s ability to effectively manage multiple alliances simultaneously. We found that different alliance types demand different alliance management capabilities and that companies with greater amounts of alliance experience were able to manage a larger number of alliances.

In a further study, we examined how different types of internal experiences can play an important role in the alliance learning process and lead to better outcomes. We focused on internal exploration experience, which enables companies to recognize and internalize external knowledge. For example, among pharmaceutical companies, those with strong R&D capabilities are best able to choose the best partners from the pool of promising startups and effectively manage their R&D projects. We also examined the role experience plays in generating value. Because combining different types of alliance experience with internal capabilities led to different results, we developed a set of contingent arguments and showed that internal and external capabilities should be considered together; managers need to evaluate whether their particular combination will help to enhance — or hurt — alliance performance.

In the face of the comparatively low success rate of alliances, it’s worth asking: Why is the rate so low? And more important: What can managers do about it? In attempting to answer these questions, we found that managers are frequently ill-prepared to handle the key stages of the alliance process. Instead, they tend to make three misguided assumptions that sow the seeds for failure: (1) that they will find good partners, (2) that they will be able to capture an adequate amount of economic value, and (3) that the alliances will continue to serve the company’s needs over time.

Assumption 1: The company will find good partners. The assumption that you will be able to line up the best partners available ignores the broader context in which alliances are formed. The market for alliance partners is often crowded and competitive. Moreover, managers often don’t have complete information to identify the best matches. During the biotechnology revolution, for example, some 2,000 new ventures burst onto the market. Many of them sought to attract the attention of the big pharma companies on the theory that an alliance would be an endorsement of quality and pave the way to a faster IPO with a high valuation.8 However, four decades after the start of biotech revolution, only a handful of biotech firms have become highly successful.9 Most of the others failed.10

Assumption 2: The company will be able to capture a reasonable amount of economic value from its partnerships. Even if you can bring a partner to the negotiating table, there is no guarantee that the deal will allow you to capture adequate value from the alliance. Strong competitive pressure often leads companies to conclude a deal quickly; not enough time is spent assessing key factors that can drive relative value capture in an alliance, such as evaluating the partner’s alternatives against your own. In other cases, companies give away too much value, fearing that the prospective partner, especially when that partner is a large, well-established company, will otherwise walk away. As a result, a company’s alliance portfolio can become unsustainable.

Assumption 3: The alliances will continue to serve the company’s needs over time. Because coordination and monitoring costs are difficult to measure, companies often work from unrealistic estimates of the value partnerships can provide. Failure to anticipate and resolve problems before they escalate, for example, can result in a significant amount of lost value. In addition, adding new alliances to existing portfolios can lead to unintended competitive repercussions.11

In one strategic alliance in the health care field, the executives who negotiated the partnership recognized that there was a lack of operational fit but assumed that the problems could be remedied as the collaboration unfolded. Unfortunately, the challenges were more serious than the executives initially thought. Due to differences in the companies’ decision-making structures that hadn’t been acknowledged and accounted for, misunderstandings and negative perceptions spiraled into personal animosities and mistrust. As ad hoc remedies were put in place, the two companies struggled to respond to competitive developments, and the less-experienced partner missed a valuable opportunity to develop a cadre of knowledgeable managers who could be assigned to work on future collaborations.

Improving Alliance Management

Prior research on alliance management tended to focus on one stage of the process — for example, how to manage a stand-alone alliance.12 This approach presents a piecemeal and truncated understanding of the relevant issues and remedies. Given factors such as globalization, technological change, and business model innovations, executives frequently need to manage multiple alliances at once with partners in different geographies and at different stages of the alliance life cycle. This requires a number of different, interrelated activities, with many opportunities for missteps. Based on our experience, we have developed a process framework and a set of critical questions that can help managers undertake alliances more effectively.

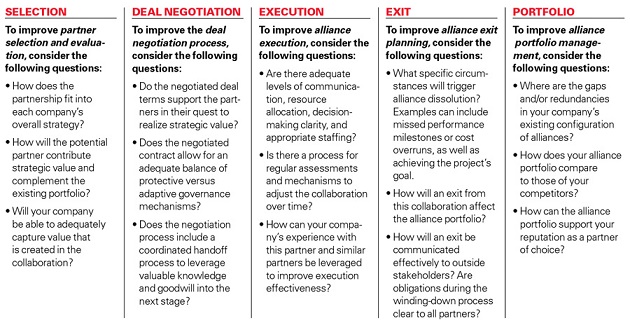

The framework acknowledges the complexity of generating benefits from alliances and the vigilance required to extract their benefits fully. For example, even if a company executes its alliances exceptionally well, the overall returns may be low because inappropriate partners were selected, too much value was ceded in negotiations, or the alliance contributes little to the company’s alliance portfolio. We offer a holistic approach to alliance management, organized around five distinct steps: partner selection, deal negotiation, execution, exit, and portfolio management. (See “Managing Alliances Effectively.”) To illustrate how the framework works, consider the example of Lego A/S, the privately held toy company based in Billund, Denmark. After facing financial difficulties in the early 2000s, Lego has been able to rebound, in part based on how it used alliances to leverage and extend its core competence.13 Between 2005 and 2015, Lego grew significantly, from about $1 billion in revenues to more than $5 billion.

Managing Alliances Effectively

Our framework highlights the distinct but interrelated stages that underpin most alliances. The framework gives rise to a set of questions that can help managers undertake each stage of the alliance process more effectively, while providing a solid foundation for the subsequent stage.

Step 1: Partner Selection Strategic alliances are voluntary arrangements between two or more organizations to develop new processes, products, or services. There are important distinctions between alliances in which partners access existing knowledge, resources, and capabilities and those that lead to the development of new knowledge, resources, and competencies.14 Our research suggests that partner selection should account for potential partners’ experiences gained through collaborations, since they shed light on the partner’s ability to contribute to the success of an alliance.15 Since external experience can be combined in complementary ways with internal competencies, potential partners should be evaluated in part on the bundles of relevant experiences they are able to bring to the alliance.16

When managers take the time to conduct thorough evaluations of this kind, they can increase the odds of successful negotiations by using the information to communicate alliance benefits to potential partners. The analysis can be used as a tool for internal communication as well, ensuring that a promising alliance can get the resources and managerial attention it requires. Potential partners shouldn’t be evaluated in a vacuum but need to be examined in terms of value-creation potential and strategic fit with the overall alliance portfolio.

Previously, Lego had selected its alliance partners based on a limited set of criteria, with the implicit assumption that if the partnerships leveraged and extended the company’s brand, they must be creating value. The company obtained licenses for intellectual property (characters and brands) such as Star Wars, Indiana Jones, Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings, Batman, the Simpsons, and Iron Man. Because Lego didn’t own the intellectual property but had to invest in the manufacturing, global distribution, and promotion of the licensed products, the benefits accrued mainly to the partners.17

Recently, Lego has become more selective in assessing and working with partners, attempting to achieve both a strategic and an operational fit. “The Lego Movie”, which grossed more than $450 million on a $60 million budget in the year following its 2014 release, offers a good example of its new approach. To produce the movie, Lego negotiated partnerships with several companies to obtain key resources and capabilities that it lacked. For example, the animation and visual effects for the movie were developed by the digital animation and design studio Animal Logic Pty Ltd, based in New South Wales, Australia, while Warner Bros. Pictures provided financing and distribution. The movie attracted audiences well beyond Lego’s traditional market of children between 5 and 12 years old.

Step 2: Deal Negotiation This stage of the process, where the parties define the terms of the partnership and their mutual responsibilities and rewards, is fraught with challenges. Negotiators who focus on capturing the lion’s share of the potential value at the expense of their partner run the risk of undermining the alliance and seeing little in actual gains. Negotiations between small and large companies are particularly susceptible to poor outcomes due to differences in the partners’ negotiating power. Negotiators for small companies warn that lopsided deal terms that result in the smaller partner assuming most of the risks can have consequences down the line, causing the small company to focus on preventing losses in the execution stage. Such responses to poorly negotiated deals can leave alliance teams less willing and less able to realize the value-creating potential of the partnership.18

A successful deal negotiation should set the stage for the execution stage and support knowledge sharing between the negotiators and the individuals who will be taking over the day-to-day execution. Corporate development teams that move through this process too quickly miss out on the opportunity to receive the feedback they need to improve future negotiations. To this end, the composition of the steering committee should be optimized to facilitate information exchange and improve coordination.19 The handoff from those negotiating the agreement to those who will manage the execution stage provides an opportunity for companies to hone their alliance capabilities.20

Although discussing the details of an exit from the relationship as it is being formed may be uncomfortable, beginning to plan for contingencies and wind-down procedures as part of the front-end negotiation is nevertheless helpful.21 Without such discussions, there is a tendency toward inertia that can mean a company’s alliance portfolio fails to reflect changing strategic and environmental conditions. For instance, when negotiating the various strategic partnerships needed for “The Lego Movie”, Lego was more explicit about defining the scope of the project than it had been in past partnerships. While some of its old alliances had been on the books for years and were becoming stale, relationships involving “The Lego Movie” were clearly defined and limited to a single project, with an option for future collaboration.

Step 3: Execution To achieve the strategic goals of the individual partners, it’s necessary to have collaboration between people from different organizations that have their own ways of doing things. Many alliances involve collaboration across geographic, industry, and sector boundaries. Successful execution requires working through the inevitable frictions to achieve new solutions and shared understanding.

With “The Lego Movie”, for example, Lego saw the need to combine detailed alliance negotiations with strong execution. It sought contractual safeguards to maintain the integrity of its brand and ensure adequate returns. At the same time, there was an understanding on the part of management that creativity — both in terms of the storyline and the visual quality — was essential. This required partners to be flexible and to maintain open communication. With this in mind, Lego wanted agreements that allowed different partners to bring their best ideas to the movie project. For its part, Lego shared core intellectual property, including software and data related to its virtual brick-building system, collaborated on new characters and set designs, and provided input to key decisions during the three-year movie-making process.

In smaller organizations, alliance experience is often limited to a few key employees. Larger companies have the opportunity to create structures, processes, and incentives to proactively harness and store their alliance experience for future use.22 Companies such as pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly and Company have invested heavily in this area, creating specialized roles that bring together the strategic commitment and internal operational know-how needed to succeed at alliances.23 Senior-level alliance champions and on-the-ground alliance leaders are, in turn, complemented by specially trained alliance managers who are able to transmit knowledge and best practices to the rest of the organization. In order to identify and overcome problems early on, it is important to deploy alliance managers, create shared tools, and conduct regular assessments of alliance health. It’s also helpful to establish conflict-resolution procedures in advance to have a road map for how specific issues will be resolved and by whom. Best practice calls for establishing a dedicated alliance function,24 which coordinates all alliance-related activities while creating systems, processes, and structures to centralize and share accumulated alliance experience.

Step 4: Exit Although some alliances end in bitter conflict, dissolving an alliance is not always a sign of failure. Since alliances can be vehicles for exploring new opportunities, it shouldn’t be surprising that some will prove to be less fruitful than initially expected. By negotiating exit triggers, partners can determine in advance when the dissolution process should begin. At Lego, for example, the purpose of many of its partnerships was to inject novelty into its product line and boost sales. However, everyone knew they weren’t meant to last forever and that most would reach a point of diminishing returns. This didn’t seem to sour companies on the idea of working with Lego. In fact, Warner Bros. was so pleased with the results of its involvement with “The Lego Movie” that it signed an agreement to produce a sequel and other spin-off movies.

Terminating an alliance should follow a process that clearly stipulates the responsibilities of the partners and the various stakeholders. Among other things, partners should agree up front about how gains and losses will be shared. The reasons for exit should be communicated clearly to both partners’ other alliance partners so as not to damage either company’s reputation. One executive we interviewed admitted that the lack of an exit plan left his company at a loss for what to do when a larger partner terminated their four-year partnership. The uncertainty and confusion that ensued led to a significant drop in his company’s stock price and a loss in shareholder value.

Step 5: Portfolio Management The combination of partners and deal structures that comprise a company’s alliance portfolio can yield additional value. At a minimum, having multiple partners reduces a company’s reliance on any single partner. A focus on lowering risk and increasing bargaining power, however, shouldn’t come at the cost of too much redundancy lest scarce resources (including managerial resources and attention) be spread thin. New partners should add complementary strengths and increase the company’s strategic flexibility rather than reducing it.25 At the corporate level, alliances should also complement the company’s acquisition strategy and internal development choices.26

Companies should conduct regular assessments of their alliance portfolios in order to ensure that future alliances fill important gaps. In the interests of advancing its ability to innovate, Lego, for example, recognizes that partnerships that are primarily about leveraging existing resources and know-how, such as licensing agreements, need to be balanced with relationships that are higher-risk and exploratory — but also more likely to lead to new generations of products. For example, a partnership with the MIT Media Lab in the 1990s gave rise to Lego’s MindStorms, build-and-program robot kits that produced a large, loyal following of both teenagers and adults. This collaboration has in turn inspired new products that mix Lego’s physical toys with digital interaction.

As a whole, our framework assists companies in managing their alliances throughout their entire life cycle. While each stage of an alliance process raises distinct issues, the stages are interconnected and can contribute to a valuable alliance portfolio. Companies can begin by assessing their existing and potential alliances with a set of questions to reveal whether the value creation and capture potential of each alliance — and the resulting alliance portfolio as whole — is being fully realized.

Ha Hoang is a professor of management at ESSEC Business School in Cergy-Pontoise, France. Frank T. Rothaermel is the Russell and Nancy McDonough Professor of Business at the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Scheller College of Business in Atlanta, Georgia.

References

1. M. Richtel, “Elon Musk of Tesla Sticks to Mission Despite Setbacks,” New York Times, July 24, 2016.

2. For a careful analysis and discussion of how to select and execute across different corporate strategy initiatives, see L. Capron and W. Mitchell, “Build, Borrow, or Buy: Solving the Growth Dilemma” (Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press, 2012).

3. For an insightful discussion of competitive implications when adding alliances to an existing alliance portfolio, see U. Wassmer, P. Dussauge, and M. Planellas, “How to Manage Alliances Better Than One at a Time,” MIT Sloan Management Review 51, no. 3 (spring 2010): 77-84.

4. Recent survey data estimates the failure of alliance portfolios to be about 50%, and Benjamin Gomes-Casseres estimates that 33%-66% of all alliances break up within 10 years. In 2001, Jeffrey H. Dyer, Prashant Kale, and Harbir Singh estimated that almost half of alliances fail. See, respectively, The Association of Strategic Alliance Professionals, “Fourth State of Alliance Management Survey,” 2012, www.strategic-alliances.org; B. Gomes-Casseres, “Remix Strategy: The Three Laws of Business Combinations” (Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Press, 2015), 12; and J.H. Dyer, P. Kale, and H. Singh, “How to Make Strategic Alliances Work,” MIT Sloan Management Review 42, no. 4 (summer 2001): 37-43. While alliances may be terminated for a host of reasons, including the achievement of the intended alliance goals, the estimates above suggest that many alliance portfolios do not deliver the expected strategic benefits. There are several explanations of why the estimated alliance failure rate has not improved over time. As the business environment has become more uncertain (due to technology change, regulatory changes, political factors, financial crises, etc.), a greater variety of external factors can limit alliance benefits. Alliances also tend to be more complex today and thus are more challenging to manage at the alliance-portfolio level. However, although the average failure rate does not appear to have changed much, if any, over time, individual companies may improve their alliance performance, as we detail in this article.

5. H. Hoang and F.T. Rothaermel, “The Effect of General and Partner-Specific Alliance Experience on Joint R&D Project Performance,” Academy of Management Journal 48, no. 2 (April 2005): 332-345; and H. Hoang and F.T. Rothaermel, “Leveraging Internal and External Experience: Exploration, Exploitation, and R&D Project Performance,” Strategic Management Journal 31, no. 7 (July 2010): 734-758.

6. R. Gulati, T. Khanna, and N. Nohria, “Unilateral Commitments and the Importance of Process in Alliances,” MIT Sloan Management Review 35, no. 3 (spring 1994): 61-69.

7. F.T. Rothaermel, “Tesla Motors, Inc.,” McGraw-Hill Education, December 17, 2015; see also E. Musk, “The Secret Tesla Motors Master Plan (Just Between You and Me)” (blog), August 2, 2006, www.tesla.com.

8. F.T. Rothaermel, “Technological Discontinuities and Interfirm Cooperation: What Determines a Start-Up’s Attractiveness as Alliance Partner?” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 49 no. 4 (2002): 388-397; and T.E. Stuart, H. Hoang, and R.C. Hybels, “Interorganizational Endorsements and the Performance of Entrepreneurial Ventures,” Administrative Science Quarterly 44, no. 2 (June 1999): 315-349.

9. F.T Rothaermel and D.L. Deeds, “Exploration and Exploitation Alliances in Biotechnology: A System of New Product Development,” Strategic Management Journal 25, no. 3 (March 2004): 201-221.

10. G.P. Pisano, “Science Business: The Promise, the Reality, and the Future of Biotech” (Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Press, 2006).

11. Wassmer, Dussauge, and Planellas, “How to Manage Alliances.”

12. Jonathan Hughes and Jeff Weiss provide fresh insights but focus on the effective management of a specific alliance. In a similar vein, Ranjay Gulati, Maxim Sytch, and Parth Mehrotra provide a helpful framework on how to plan an exit from a specific alliance. Other authors highlight the importance of a dedicated alliance function. By contrast, we focus on the entire alliance process from initiation to termination in a holistic fashion, as well as providing guidance pertaining to alliance portfolio management. In sum, our approach is more strategic in nature, and thus more likely to help companies gain and sustain a competitive advantage. See J. Hughes and J. Weiss, “Simple Rules for Making Alliances Work,” Harvard Business Review 85, no. 11 (November 2007): 122-131; R. Gulati, M. Sytch, and P. Mehrotra, “Breaking Up Is Never Easy: Planning for Exit in a Strategic Alliance,” California Management Review 50, no. 4 (summer 2008): 147-163; and Dyer, Kale, and Singh, “How To Make Strategic Alliances Work.” For a complementary treatment on how to create and capture value from broader corporate development activities including alliances, joint ventures, and acquisitions, see Gomes-Casseres, “Remix Strategy.”

13. F.T. Rothaermel, “Lego’s Turnaround: Brick by Brick,” in “Strategic Management: Concepts,” 3rd ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2016), 457-459.

14. F.T Rothaermel and D.L. Deeds, “Exploration and Exploitation Alliances in Biotechnology: A System of New Product Development,” Strategic Management Journal 25, no. 3 (March 2004): 201-221.

15. Hoang and Rothaermel, “Leveraging Internal and External Experience.”

16. A.M. Hess and F.T. Rothaermel, “When Are Assets Complementary? Star Scientists, Strategic Alliances and Innovation in the Pharmaceutical Industry,” Strategic Management Journal 32, no. 8 (August 2011): 895-909.

17. H. Hoang and F. Brice, “Rebuilding Lego Group Through Creativity and Community,” INSEAD case study (Fontainebleu, France: INSEAD, 2007).

18. J. Lerner, H. Shane, and A. Tsai, “Do Equity Financing Cycles Matter? Evidence From Biotechnology Alliances,” Journal of Financial Economics 67, no. 3 (March 2003): 411-446. The academic literature highlighting how contracts and governance support alliance goals is summarized in D.J. Schepker, W.-Y. Oh, A. Martynov, and L. Poppo, “The Many Futures of Contracts: Moving Beyond Structure and Safeguarding to Coordination and Adaptation,” Journal of Management 40, no. 1 (January 2014): 193-225.

19. Adaptive partnership governance is discussed by F.A. Martinez-Jerez, “Rewriting the Playbook for Corporate Partnerships,” MIT Sloan Management Review 55, no. 2 (winter 2014): 63-70.

20. An extensive literature dissects these challenges and offers strategies and tactics to boost the likelihood of a successful negotiation. See, for example, D.A. Lax and J.K. Sebenius, “3-D Negotiation: Powerful Tools to Change the Game in Your Most Important Deals” (Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press, 2006).

21. Gulati, Sytch, and Mehrotra, “Breaking Up Is Never Easy.”

22. F.T. Rothaermel and D.L. Deeds, “Alliance Type, Alliance Experience, and Alliance Management Capability in High-Technology Ventures,” Journal of Business Venturing 21, no. 4 (2006): 429-460.

23. Hoang and Rothaermel, “The Effect of General and Partner-Specific Alliance Experience”; and Hoang and Rothaermel, “Leveraging Internal and External Experience.” For a careful study of the positive performance impact of dedicated alliance functions in large companies, see P. Kale, J.H. Dyer, and H. Singh, “Alliance Capability, Stock Market Response, and Long-Term Alliance Success: The Role of the Alliance Function,” Strategic Management Journal 23, no. 8 (August 2002): 747-767.

24. Dyer, Kale, and Singh, “How to Make Strategic Alliances Work”; and Kale, Dyer, and Singh, “Alliance Capability.”

25. D. Lavie, “Alliance Portfolios and Firm Performance: A Study of Value Creation and Appropriation in the U.S. Software Industry,” Strategic Management Journal 28, no. 12 (December 2007): 1187-1212.

26. Capron and Mitchell, “Build, Borrow, or Buy.”

Reprint 58119.

For ordering information, visit our FAQ page. Copyright © Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2016. All rights reserved.