![]()

3

Writing a Performance

Work Statement for

Performance-Based

Service Contracting

Performance-based service contracting (PBSC) is a new term for a contracting technique that has been in use for years. Recently, however, PBSC has become a preferred technique for service contracting, and detailed guidance on its use has been published. The new emphasis may make it seem that the performance work statement (PWS)—which is essentially the SOW for PBSC—is something totally different from a typical SOW. This is not the case, however. While there are some differences, they are found primarily in documents attached to the PWS, rather than in how the PWS is written. This chapter discusses the PBSC concept, and Chapter 5 will cover the format and contents of any SOW, including the PWS.

WHAT IS PERFORMANCE-BASED SERVICE CONTRACTING?

Performance-based contracting can be defined as the structuring of all aspects of an acquisition around the purpose of the work to be performed, with the contract requirements set forth in clear, specific, and objective terms with measurable outcomes as opposed to either the manner by which the work is to be performed or broad and imprecise statements of work. The FAR states that:1

Performance-based contracts for services shall include —

(1) A performance work statement (PWS);

(2) Measurable performance standards (i.e., in terms of quality, timeliness, quantity, etc.) and the method of assessing contractor performance against performance standards; and

(3) Performance incentives where appropriate. When used, the performance incentives shall correspond to the performance standards set forth in the contract.

PBSC is a contracting concept in which the contractor is paid based upon its attainment of predetermined contractual goals. The PBSC work requirement is described in terms of what is to be accomplished, the performance standards the contractor is to meet, how these performance standards will be measured, and how the contractor’s performance will be monitored with respect to the performance standards. This concept is designed to ensure that:

(1) Contractors are free to determine how to meet the performance objectives

(2) Appropriate performance quality levels are achieved

(3) Payment is made only for services that meet the performance quality levels.

PBSC involves significantly more planning and development effort than that required for a typical service requirement using a functional SOW, and sufficient time must be allowed for this activity. If the initial planning effort is not done well, the resulting contract will pose continuing problems and probably result in a much lower quality of services than anticipated.

The success of PBSC depends primarily on careful development of three specific components: a PWS, a quality assurance plan (QAP), and, when appropriate, an incentive plan.

Performance Work Statement

The PWS is a document that describes the required services in terms of the expected results or work outputs. The PWS is similar to the functional SOW in that it includes such elements as “what, when, where, how many, and how well” the work is to be performed. However, it goes into greater detail than the functional SOW by expressing the work outputs as performance indicators with objective, measurable performance standards and associated acceptable quality levels (AQL) that express the allowable variance from the performance standards. This approach facilitates assessment of the quality of work performance. Other than how the work outputs are described, the contents of a PWS are the same as those found in a functional SOW.

Most government service requirements are similar to those provided in the commercial marketplace. The PWS should reflect the terms and conditions and the performance standards of the commercial marketplace to the maximum extent practicable rather than establishing unique government requirements and performance standards. Reserve unique requirements or standards for those instances where they are critical for successful contract performance.

Quality Assurance Plan

The QAP addresses what the government must do to ensure that the contractor has performed in accordance with the performance standards. It reflects the established performance indicators and related performance standards and states how contractor performance will be monitored and measured (i.e., surveillance methods) to determine the extent to which the contractor is in compliance with the performance standards. The QAP may be incorporated into the PWS but is usually described in a separate document as an attachment to the PWS. It is not unusual to have multiple QAPs, each reflecting different surveillance methods for different tasks.

Incentive Plan

When PBSC is used, the FAR2 encourages the use of financial incentives in a competitive environment to encourage contractors to develop innovative and cost-effective methods of performing the work. The incentive structure should relate the contractor’s performance to the PWS and QAP to reward contractors who perform well and penalize those who do not perform to the required standards. It should be noted, however, that incentives should be used only when appropriate.3

The incentive plan may be included as part of the QAP or set forth in a separate document as an attachment to the QAP. Generally, if deductibles are used, they are addressed as part of the QAP; if award, formula, or term incentives are used, they are addressed in a separate document attached to the QAP. The use of incentives is addressed in greater detail at the end of this chapter.

WHEN IS IT APPROPRIATE TO USE PBSC?

Service contracts usually involve the contracting out of a function previously performed by government personnel or one that supports a government function. The use of PBSC is most appropriate for services that can be defined in terms of objective and measurable performance outcomes, such as guard services, transportation services, maintenance and repair services, administrative services, and some technical services. Services that are repetitive in nature and represent a continuing requirement are particularly appropriate for PBSC because the time and effort to establish the initial contract can be amortized over time. Moreover, the PWS for successor contracts will need updating only to the extent that actual experience or changed requirements dictate.

Do not, however, simply copy the RFP/PWS from a previous contract. At a minimum, market research and analysis, as well as a review of how the work is actually being accomplished, are required to ensure that there have not been changes since the last contract was awarded.

Services that require creative thinking (such as R&D) or a highly skilled technical effort often do not have definable outcomes in terms of measurable performance outcomes. If the end product of the work effort cannot be specifically defined at the onset of the procurement (i.e., in the RFP), it does not lend itself to the detailed definition required for the successful use of PBSC (but see Chapter 4 on the SOO concept). Do not try to force-fit an inappropriate effort into a PBSC mode. This will only cause problems.

DEVELOPING A JOB ANALYSIS

The PWS describes the required services in terms of the expected work outputs (performance indicators) of each task, the performance standards (required quality level) for each output, and any permissible deviations (acceptable quality level) from the established performance standard. These are determined through job analysis (DoD uses the term “performance requirement analysis”). Job analysis involves examining the requirement and the kinds of services and outputs needed and provides the basis for establishing performance indicators and related performance standards.

Job analysis examines how a service requirement is currently performed (plus any known changes to be implemented during contract performance), either by in-house staff or the incumbent contractor, to determine the actual work results or products. When conducting job analysis, it is essential to distinguish between what is actually being done and your perceptions of what is being done. Organizations, missions, and how work is performed can change over time, both formally and informally. Job analysis should be performed on the basis of an onsite audit of what is actually being done.

Some sort of job analysis is required for the development of any SOW. The job analysis required for a PWS is more detailed than that required for a functional SOW because of the need to develop performance indicators, standards, and acceptable quality levels; a QAP; and, when using incentives or deductibles, performance values to tie into the incentive structure.

Organizational analysis

Data gathering (workload, facility, and resource)

Directives analysis

Market research

Work analysis

Performance analysis

Cost analysis.

Organizational Analysis

Organizational analysis is an internal activity (as opposed to external activities, which examine the commercial marketplace) that involves an examination of the organizational unit supported by the required services to see how it is organized (i.e., its place in the agency’s organizational structure and its relationship to other organizational units), its mission (i.e., what services the organizational unit provides as its work product), and what services it currently provides and how it provides them (i.e., by in-house or contractor personnel).

Organizational analysis involves the following steps:

Examine the organizational unit to be supported by the required services.

Examine the service function as it is currently performed to see how it is organized and what kind of services it provides.

Identify the organizational unit’s mission, the other organizational elements supported, and the services currently performed by each element of the organizational unit.

Identify the services performed in terms of routine services and contingent or emergency services, as appropriate.

Distinguish between what is currently being done and any changes in the workload or work processes that will be required during the period of contract performance.

Organizational analysis focuses on the activity to be contracted out. The analysis of other organizational functions should be limited to a general description sufficient to identify any interfaces of the unit in question with other organizational units.

Data Gathering

Data gathering is also an internal activity. It is the process of obtaining as much information as possible on anticipated workloads and facilities or resources required. The following types of data are usually collected:

Workload Data. The contractor must be provided an estimate of the anticipated workload for use in preparing and costing its proposal. The government also uses this information to develop the government cost estimate and to analyze the facilities and resources necessary to perform the work. Workload estimates must be as accurate as possible. Examine available historical information on the workload of the organizational unit involved as well as how this workload was measured (this may affect how the job analysis is conducted). Then determine if there are any changes anticipated in the workload during the period of the contract. Changes in organization, mission, laws or regulations, processes or procedures, and technology are just some of the changes that can affect the workload during future contract performance. These changes should be identified, and how and when they might affect contract performance should be determined.

Facility Data. The contractor must also be informed of any government-furnished facilities, equipment, data, or services that will be provided during contract performance. The contractor needs this information for proposal preparation, and the government needs it to make arrangements for delivery of the government-furnished items. Examine the facilities, equipment, data, and services currently used in performing the effort to be contracted out, and determine the benefit to the government of providing all or some of these items. If anticipated changes will affect the facility data, this should be reflected in the data collected.

Resource Data. Determine the number and types of inhouse personnel (or incumbent contractor personnel) currently used. This information is needed to prepare the government cost estimate and to provide a basis for evaluating proposals. The government must have its own idea of the resources necessary to do the work in order to evaluate what the contractors propose.

This resource information should not be provided in the PWS. Identifying the number and types of personnel required (using job titles or other qualifiers such as college degrees or years of experience) is not appropriate for performance-based contracting because it may inhibit the contractor’s ability to propose its own methodology and resources for meeting the requirement. Contractors often believe that they cannot deviate from the requirements set forth in the RFP and therefore may not propose innovative methodology using different resources.

The PWS should describe the requirement in a manner that permits the contractor to propose whatever number and types of personnel it believes will best meet the requirement. Once the proposal is submitted, the evaluators will assess the proposal, including the proposed resources, to determine the feasibility of what is proposed and eventually which proposal offers the best value.

Resource requirements should be examined to determine if there are any constraints, such as the need for security clearances, that might affect the resources the contractor proposes to provide. Such constraints must be set forth in the PWS.

Directives Analysis

A directives analysis involves examining all currently applicable directives relevant to the operation of the services to be contracted out to determine which must be identified in the PWS. Directives that govern how the contractor must perform and would therefore affect how the contractor prepares its proposal must be identified. (See Chapter 5, Applicable Documents, for how this information should be presented).

Market Research

Market research is critical for the development of a PWS. The key concerns are how commercial services are organized and staffed, the work outputs or products, performance indicators, performance standards, and acceptable quality levels (performance metrics and measurements), particularly if the services have not been previously procured on a performance-based basis. Even if the services have been previously procured using a PWS, market research will reveal if there have been changes in techniques or methodology that will benefit the current acquisition.

Basic market research was discussed in Chapter 2, and certain other market research aspects are addressed in Chapter 4. All of this information applies to the development of both a PWS and a standard SOW.

Work Analysis

The organizational analysis, data gathering, directives analysis, and market research provide the basis for the work analysis. Work analysis is the process of identifying the required work products (or outputs), breaking them down to their lowest task level, and linking them in a logical flow of activities. In essence, this is a work breakdown structure expressed in terms of the work product or output required. The result is the identification of those work products expected of the contractor.

Work analysis identifies the three components of a work requirement (by task, and subtask if appropriate):

Work Inputs. Work inputs are those actions or documents needed to initiate the work activity.

Work Steps. Work steps are those actions that must taken to actually accomplish the work.

Work Outputs. Work outputs are those items produced by the work steps. They provide the means to quantify and measure the contractor’s performance.

This information is needed to develop an overall picture of the requirement, what needs to be accomplished, and any constraints that might apply. Work outputs are the primary product of work analysis. The work outputs provide the basis for performance analysis.

Performance Analysis

Performance analysis is the process of examining the results of the work analysis and determining how the key work outputs of each task or subtask can be measured (developing a performance indicator), developing the acceptable performance level (the performance standard), and determining the permissible deviations (the acceptable quality level, or AQL). Work analysis has identified the tasks/subtasks that must be accomplished to meet the government’s requirements. Performance analysis provides the means to determine if the contractor has satisfactorily met those requirements.

Performance Indicators

Generally, performance indicators are the work output for each task, expressed in terms of something that can be measured, such as quantities or quality. Performance indicators must not only be realistic and meaningful in terms of the effort being performed, but must also indicate accomplishment of a significant event in terms of the task or subtask involved.

Performance indicators are developed by dividing the overall work requirement into tasks (and subtasks, as necessary) and analyzing each task or subtask to determine its required outputs or results. Some outputs are difficult to express in measurable terms, and others do not represent critical factors in successful performance. Work outputs that are not significant or that are difficult to express in measurable terms should, if possible, be included as part of another output that can be quantified. Performance indicators should be developed only for those outputs that demonstrate accomplishment of a significant task or subtask. Keep the number of performance indicators to a minimum, because too many will unnecessarily complicate contract administration.

The PWS must fully describe each task and subtask (see Chapter 5) in terms of what is to be accomplished. The performance indicators, performance standards, and AQL should be expressed at the end of the task or subtask description as the criteria for determining whether the requirements are met.

One of the dangers in PBSC is the development of a complicated contract that contains so many different elements to monitor that the agency resources to administer the contract are overwhelmed and cannot adequately perform the task. For example, imagine a requirement to provide on-base personnel transportation at a large military installation. The requirement has two tasks: (1) Operate Vehicles and (2) Maintain Vehicles. The Operate Vehicles Task has three subtasks: (1) On-Call Taxi Service, (1) Scheduled Bus Service, and (3) Unscheduled Bus Service (for special occasions, i.e., conferences, tours). Figure 3-1 shows the subtask On-Call Taxi Service, broken down into four performance indicators: response time, accidents per mile, operational cost per mile, and taxi in-commission rate. All of these are indicative of how well a taxi operation is performed.

Subtask 1 contains four performance indicators, each of which could also apply to subtasks 2 and 3. Thus the overall requirement for personnel transportation could contain 12 performance indicators, each of which must be monitored during contract performance. What if Task 2: Maintain Vehicles also had three subtasks, each of which had four performance indicators? This would total 24 performance indicators, each of which must be individually monitored throughout contract performance. The point at which the requirements become too much to handle will vary, but most agencies would be reluctant to dedicate more than one or two people to monitoring a contract.

This problem can be avoided by exercising discipline when conducting a performance analysis and identifying only those activities that are critical to the work at hand. In the Figure 3-1 example, which of the four performance indicators is most important to assessing the success of the taxi service? If a team was used to identify the performance indicators, the customer representative might choose response time, the safety representative might choose accidents per mile, the comptroller representative might choose cost per mile, and the maintenance representative might choose the in-commission rate. Each group has its own perceptions of a successful operation, but it is not practical to try to satisfy everyone.

FIGURE 3-1:

Subtask 1: On-Call Taxi Service

Once all the possible performance indicators have been identified, the next step is to analyze objectively what is really important, considering the other tasks and associated performance indicators that must be covered in the contract. The answer is easy in this instance. The primary success indicator for a taxi service is response time. The accidents per mile and in-commission rate are subsets of the response time in that problems in these areas will adversely affect the response time. The cost per mile depends on who is footing the bill; if the contract is cost-reimbursement, this could be an important factor and might be included as a second performance indicator. Otherwise, response time is the only performance indicator needed.

The same thought process applies to the bus subtasks. The only critical performance indicator is response time. Thus, instead of 12 performance indicators for vehicle operations, only three need to be monitored. This eases the monitoring resource requirements significantly.

Performance Standards

Performance standards express the level of performance required by the government. They are the yardsticks used to measure performance indicators and determine the extent to which the contractor is producing a quality output. Performance standards must be realistic (i.e., attainable) and generally should not exceed the level of performance considered acceptable when the work is performed by government personnel or by the incumbent contractors. Performance standards are expressed in quantifiable terms, such as a rate of performance (x number per hour, x minutes per job), quantities, time, events, or any other term that can be measured objectively.

Generalized standards, such as cleanliness or workmanship, can be used, but they require subjective evaluation on the part of the government. If they are used, the PWS should define the terms used and explain how the standard will be measured. This may prove difficult to do because generalized terms are most often used when a definitive standard cannot be developed. Generalized standards should be avoided in PBSC (but see Chapter 4 on SOOs).

Performance standards can be designed specifically for the work at hand or can come from published sources, such as government standards, industry-wide standards (e.g., ISO 9000, 9001, and 9002), standards established by industry associations, government regulations or directives, or locally developed standards. Generally, industry-established standards should be used, if available, because contractors understand and accept these standards and their use will enhance the competition.

Setting reasonable performance standards is very important in PBSC. If the standards are complicated and difficult to measure (e.g., require a lot of ongoing contract surveillance, time-consuming testing), contract administration will be burdensome for both the contractor and the government. If the standards are too high, their attainment will be more costly than necessary. If the standards are too low, the government may not receive the benefits it should from contract performance.

In the taxi example, the performance standard is expressed in terms of how quickly the taxi responds (i.e., four minutes). This number, however, must be reasonable and must have a rational basis. Some of the factors to be considered, for example, should be the distance to be traveled, speed limits, traffic congestion, road conditions, and any other local factors that might affect the response time.

The performance standard should be based on an achievable average time under any conditions. Do not establish a time frame that might require the taxi driver to speed or otherwise drive in an unsafe manner. While it is possible to develop multiple response times (for example, to take into account rush hour or adverse weather conditions), this is usually not a good idea because it overcomplicates the standards. Keep in mind that government personnel must be assigned to monitor the contractor’s performance and to measure its compliance with each of the standards. Multiple standards unnecessarily complicate contract administration.

Acceptable Quality Level

The AQL expresses the allowable variation from standard that will still result in an acceptable level of quality—that is, the maximum allowable error rate or variation from the standard. The AQL is usually expressed as a percentage variance from the standard; for example, an AQL of 5 percent means that the work must be performed to the standard 95 percent of the time. The AQL recognizes that despite a contractor’s best efforts, things do go wrong, and 100 percent compliance with the performance standard (an AQL of 0 percent) is often an unrealistic and expensive goal. There are, however, instances where an AQL of 0 percent would be appropriate; for example, for health and safety tasks or other tasks that, for project purposes, must be performed to standard. Each performance standard must be assessed and an AQL assigned that recognizes the realities of contract performance.

A published standard will usually indicate the AQL. If a published standard is not available, historical workload data should be examined to determine what variance has been acceptable in the past. Generally, the AQL should reflect the same variance from the standard that was applied when the government (or incumbent contractor) performed the work. It would be a good idea to document (for the file) how the AQL was established, particularly if the AQL has been changed from that previously used.

Performance Requirements Summary

The results of the organizational analysis, data gathering, directives analysis, market research, and work analysis represent the end products of job analysis and provide the information needed to accomplish the performance analysis. This information is usually presented in a performance requirements summary.

The performance requirements summary presents the performance indicators (work requirements expressed in terms of the work output), the performance standards (how the performance indicators will be measured to determine successful performance), and the AQL (allowable variance from the performance standards) in a table format, usually as an attachment to the PWS. A performance requirements summary table would be required for each contract task. When a deductible is used, a percentage is used to note the value of the performance indicator and the amount to be deducted for services not provided or not meeting acceptable quality standards.

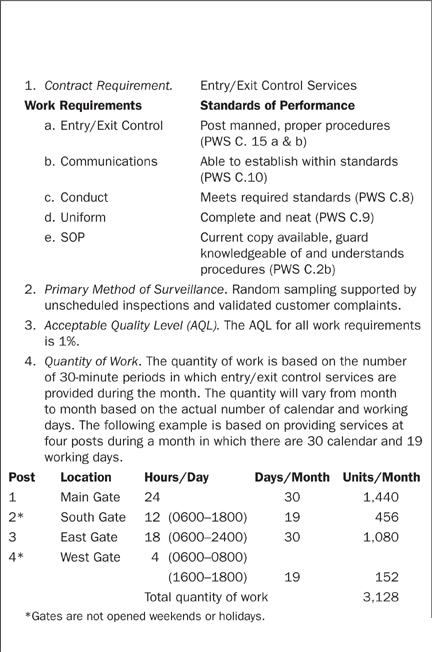

Figure 3-2 is an example of a performance requirements summary table taken from one of the model PWSs that can be obtained from the Office of Federal Procurement Policy (OFPP). This example shows only one of the seven tasks under the contract.

Cost Analysis

Cost estimates, based on available data, should be prepared for each service or output on a continuing basis as the requirement is refined. The cost estimates are used in preparing the government estimate, determining incentive structures when the use of incentives is appropriate, and evaluating proposals.

FIGURE 3-2:

Performance Requirements Summary Table

For Defense Department (DoD) Readers

It should be noted that the foregoing information is presented somewhat differently by DoD.4 DoD refers to the analytical process as performance requirement analysis and describes it in three steps:

Define the desired objectives. What must be accomplished to satisfy the requirement? List what needs to be accomplished to satisfy the overall requirement. Techniques: (1) Use an interview or brainstorming approach with the customer (user) to determine all dependent variables (what, when, where, who, quantity, quality levels, etc.) or (2) review previous requirements for validity and accuracy.

Conduct an outcome analysis. What tasks must be accomplished to arrive at the desired outcomes? Identify specific performance objectives for those outcomes defined in the previous step. Techniques: (1) Segregate desired outcomes into lower task levels and link those tasks together into a logical flow of activities or (2) use a tree diagram to outline each of the basic outcomes.

Conduct a performance analysis. When or how will I know that the outcome has been satisfactorily achieved, and how much deviation from the performance standard will I allow the contractor, if any? Identify how a performance objective should be measured and what performance standards are appropriate (including acceptable quality levels).

The DoD guidebook also suggests a more extensive performance requirements summary (PRS), saying that the PRS is the baseline for the PWS and that the PRS should be brief and should capture the salient elements of the requirement. In the actual PWS, the acquisition team will elaborate on and describe the requirement in greater detail. The ultimate goal is to describe the requirement in a way that allows an offeror to understand fully what will be necessary to accomplish the requirement. The guidebook suggests using a PRS matrix with the following headings: performance objective, performance standard, acceptable quality level (AQL), monitoring method, and incentives.

While the DoD language is somewhat different from that in this chapter, the intent and the results are the same.

DEVELOPING A QUALITY ASSURANCE PLAN

In PBSC, the government must ensure that it receives the quality of services called for under the contract and pays only for the acceptable level of services received. The QAP is used to inform both contractor and government personnel how the government will monitor the contractor’s performance to determine the extent of the contractor’s compliance with the established performance standards. The QAP summarizes the quality requirements (i.e., performance indicators, performance standards, and AQL) for each task, indicates the type and level of surveillance (including the sampling procedures, as appropriate), states how the surveillance results will be evaluated and analyzed, explains how these results will affect contract payments, and includes samples of the forms to be used. The government also uses the QAP to determine the resources and procedures needed for contract administration.

Because the QAP is based on the performance indicators and standards established in the PWS and because the methods of surveillance for each task may differ, there may be a need to develop a QAP for each task. The QAP commits the government to a particular course of action during contract administration, and the government must monitor the contractor’s performance in accordance with each published QAP. Keeping the number of performance indicators to a minimum will simplify contract administration.

Because of the close relationship of the PWS and the QAPs, both should be developed within the same time frame. Generally, the QAPs should be included as an attachment to the PWS to ensure their visibility.

Do not confuse the QAP with a contractor’s internal quality control or quality assurance plan, which is a contractor’s internal plan for how it will ensure that a quality product is delivered—it is entirely separate from the government-developed QAP.5 DoD uses the term “performance assessment plan” instead of “quality assurance plan” and the term “assessment” instead of “surveillance” to avoid confusion between the terms.

Types of Surveillance Methods

Surveillance methods are a key part of the QAP. They describe how and when the government will monitor contractor performance. Surveillance methods must be tailored for the specific requirements, using the method or methods most appropriate for the specific activity to be monitored. A number of different surveillance methods are available. The following are the more commonly used methods:

100-percent inspection. This method is appropriate for infrequent tasks or tasks with stringent performance requirements where complete compliance is critical to success, such as tasks involving health and safety issues. With this method, performance is monitored at each occurrence. Because 100-percent inspection is administratively expensive in terms of time and manpower during contract administration, this method should be used only when absolutely necessary.

Random sampling. This is the most commonly used method for recurring tasks, probably because the use of tables and mathematical formulas gives an impression of accuracy not found in the other methods. With this method, services are sampled to determine if the level of performance is acceptable. Random sampling works best when the number of instances of the services being performed is very large and a statistically valid sample can be obtained.

The problem with this method is that it can lead to a complicated surveillance process. Moreover, if the number of samples to be observed exceeds the manpower available to make the observations, contract administration can be difficult.

Periodic inspection. This method calls for the surveillance of tasks on other than a 100-percent or random basis. It is appropriate for tasks that occur infrequently and do not require 100-percent inspection. Periodic inspection, or planned sampling, involves the development of a surveillance plan based on subjective judgment and an analysis of available agency resources to determine which tasks to inspect and how frequently to inspect them.

This method requires careful assessment of the various tasks and informed judgment regarding what to inspect, how to inspect it, and the frequency of inspection. While this method permits the tailoring of the surveillance to the available resources, it often appears more difficult to develop than the use of random sampling and related mathematical formulas. Periodic inspection is often overlooked for this reason, even though it can simplify contract administration.

Customer input. This method can be used as a supplement to the other methods, but it is rarely appropriate as the primary surveillance method. Basically, it is a customer complaint system. Contractor performance is measured by the number and types of customer complaints about contractor performance. This is done through customer surveys and the use of customer complaint forms. It can be a valuable support method for services that are rendered to third parties, such as repair or janitorial services.

However, this method requires extra administrative effort. Procedures must be developed and personnel assigned to manage the complaint system. Customer complaints must be documented, preferably through the use of standardized forms either provided to the customers or used to record verbal complaints and, as appropriate, validated. When a customer complaint system is used, it must be managed in a manner that clearly demonstrates that the complaints are being acted upon. If the customers perceive that their complaints are not being remedied, they will cease making formal complaints regardless of the quality of the services.

Unscheduled inspections. Unscheduled (surprise) inspections are observations made at the times and places deemed appropriate by the contract monitors. In theory, such inspections provide an unbiased picture of contractor performance because the contractor has no way of anticipating when they will occur.

Unscheduled inspections should be relied on only to provide a snapshot of an instance of contractor performance and not to provide a continuing performance picture. PBSC contracts should be monitored on the basis of the contractor’s overall performance, not isolated instances of performance. For this reason, unscheduled inspections should not be used as a primary surveillance method. They are effective, however, as a support method used when the primary surveillance method indicates problems.

Selecting Surveillance Methods

Surveillance methods and schedules are influenced by a number of factors, including the number (population) of different service activities (performance indicators) to be inspected; the importance, characteristics, and locations of the activities to be inspected; and the criticality and cost of the activity. In a contract with multiple tasks and subtasks, each task/subtask should be examined and an appropriate surveillance method selected. This will probably result in a number of different methods being employed under the same contract.

When selecting the surveillance methods, available resources should be kept in mind. The surveillance process includes scheduling, observing, documenting, accepting service, and determining payment due. If available resources are not sufficient to monitor the contract properly, a functional SOW should be used instead of PBSC. The benefits of PBSC are realized only when the contract is structured properly and monitored effectively.

Surveillance should be comprehensive, systematic, and well documented. This does not mean, however, that the process must be complicated. Cumbersome and intrusive process-oriented surveillance methods that are difficult to administer and interfere unduly with contractor operations should be avoided. It is important to keep the contract monitoring process and its documentation as simple and cost-effective as possible.

If development of the surveillance process starts to get complicated, the PWS should be reviewed and the performance indicators (what is being measured) simplified. The key to simplification is to keep the number of performance indicators—not the different surveillance methods—to a minimum.

QAP Example

Figure 3-3 is an example of a QAP. It is based on one of OFPP’s model PWSs. The model PWS is for a guard services requirement consisting of seven work requirements:

Entry/exit control services

Roving patrol services

Courier services

Scheduled escort services

Miscellaneous services

Administrative requirements

Indefinite quantity work.

The PWS contains a QAP for each of these requirements, reflecting the differing surveillance plans for each requirement. The following example QAP is based on the first work requirement. Certain changes have been made for readability, but these changes do not affect the substance of the QAP.

This is just one example of how a QAP might be structured; the actual structure and content of a QAP should be tailored to the specific services required. There is no official format, but a typical QAP should:

FIGURE 3-3:

Quality Assurance Plan #1 Entry/Exit Control Services

Describe the work requirements in terms of performance indicators, performance standards, and acceptable quality levels (or maximum error rates)

Identify the surveillance methods to be used

Describe how performance will be measured (e.g., evaluation periods, sample size, sampling procedures, level of surveillance)

Describe how the performance measurements will be evaluated

Describe how the evaluation results will be analyzed

Describe how the evaluation results will affect contract payments

Provide samples of the forms to be used, such as evaluation worksheets, customer complaint forms, and the forms used to calculate contract payments (these forms will differ depending on the contract type and incentive used).

OFFERING INCENTIVES

The use of incentives in performance-based service contracting is encouraged but not required by the FAR. Generally, contractors are self-incentivized to provide something more than just satisfactory services to improve their competitive position. Contractual incentives seek to enhance this self-motivation and encourage contractors to increase efficiency and maximize performance to an extent that might not otherwise be emphasized. To be effective, contractual incentives must meet all of the following criteria. They must:

Motivate the contractor to the desired level of performance

Clearly communicate what is desired

Be realistic and achievable—the contractor must be able to attain the highest level of performance

Be controllable—the contractor must be able to control or influence the incentivized elements.

The application of an incentive arrangement will not automatically bring about improved performance. For example, if the services are already being performed at a high level of quality, it is unlikely that the use of an incentive will result in a yet higher level of quality. If, given the nature of the work, it is unlikely that performance can be improved by innovative concepts, incentives will not be effective. If the contract funds are not sufficient to generate an incentive amount large enough to encourage the contractor to change its procedures and develop more efficient and effective performance methods, the incentives will not bring about improvements. If the contract represents a small percentage of the contractor’s total sales, the contract may not receive the management attention necessary to bring about improvements in the incentivized areas.

The use of incentives is based on the assumption that a contractor is motivated primarily by profit. While this is true with regard to a contractor’s overall business, a contractor is not necessarily motivated by the profit possibilities of an individual contract. Non–profit-oriented reasons that might motivate a contractor to compete for a contract include:

The business prestige and reputation related to holding the contract

As an aid in the recruitment and retention of key personnel

The attraction of new business

An interest in entering or becoming stronger in a particular field

The need for a broader business base to control overhead costs.

If a contractor wants a contract for non–profit-oriented reasons, it may be willing to take the contract for little or no profit just to get the business. While the contractor will naturally seek to perform well (to be in a position to attract future business), specific incentives may not be effective.

Before constructing an incentive arrangement, you must consider how contractors’ business strategies might be motivated by the incentives. Effective incentives are difficult to construct; if not done properly, they can bring more trouble than they are worth. A PBSC incentive should be used only when it is determined that the incentive arrangement will motivate contractor performance that might otherwise not be achieved.

Formula Incentives

The fixed-price incentive (FPI) contract and the cost-plus-incentive fee (CPIF) contract are formula-type incentives. These are arrangements in which positive and negative incentives are based on target numbers and applied by a mathematical formula, depending on the extent to which the contractor exceeds or fails to meet the target numbers.

All formula incentives must contain an incentive on cost. If incentives are desired on other areas, such as performance quality and timely delivery, these must be in addition to the cost incentive. This is necessary to prevent a contractor from concentrating its efforts on the other incentive areas at the expense of cost. Multiple incentive contracts are very difficult to develop because the relative value of the various incentives must be continuously balanced, one to the other, to ensure a proper incentive application. For example, if quality and cost were incentivized, you would have to strike a balance between the increments of quality improvement and the increased cost of such quality improvements. Add a delivery incentive, and you would have to strike a balance among the increments of quality improvement, the increments of delivery improvement, and the associated cost increases.

A major problem with formula incentives is that they are applied mechanically and do not necessarily reflect the realities of contract performance, especially when there have been a number of contract changes during the course of contract performance. This is particularly true of multiple-incentive contracts because contract changes will affect the balance among the various incentives, jeopardizing the effectiveness of the entire incentive arrangement.

FPI contracts can become disastrous to a contractor if performance costs reach the price ceiling and further modifications to bail out the contractor are not possible. Without a contract modification that increases the price ceiling, the contractor must complete the contract at its own expense. This has happened on a number of major systems acquisitions in the past. This is not a problem with CPIF contracts because there is no price ceiling, but cost overruns, particularly when there are numerous contract changes, can be anticipated.

Over the years, numerous studies have been conducted to quantify the effectiveness of formula incentives. These studies have either been inconclusive (because contract changes during performance made such quantification impossible) or have found that incentives had little or no direct effect on a contractor’s performance.6 Despite the fact that the FAR and policy makers tout the use of FPI and CPIF contracts, these incentives offer little definitive payback, particularly in service contracts.

Award Incentives

The cost-plus-award fee (CPAF) contract is the most commonly used award incentive, but an award package may also be used with a fixed-price contract. Award incentives are arrangements in which the incentive is expressed as a total dollar amount to be divided up and paid out periodically during contract performance. The amount of the available award fee to be paid after each award fee period is based on the government’s subjective assessment of the quality of the contractor’s ongoing performance in relation to stated evaluation factors. These factors can include cost control, performance quality compared to stated performance factors, and delivery performance. If structured and administered properly, an award incentive can bring about improved quality in contractor performance, particularly with respect to services.

Award incentives work because they are flexible (incentive goals and criteria can be changed during contract performance to reflect the realities of contract performance), the award amount is determinable (the contractor can calculate the portion of the award amount available for each portion of contract performance), and the increased management attention required by this arrangement—on the part of both the contractor and the government—can create a team approach that in itself increases the likelihood of improved efficiency and effectiveness.

High-level management attention is critical to the success of an award fee arrangement. The award fee determination (payment) is made by an agency official at a level higher than both the contracting officer and the project manager, and this determination, which is in essence a report card on the contractor’s performance, is provided to a similarly placed contractor official at a level higher than the contractor’s program manager. Reporting contract performance at a level higher than the project manager is likely to get everybody’s attention, particularly if there are problems (the boss wants to know why), and this increases the potential for an effective dialogue between the government and the contractor personnel that will enhance contractor performance.

While award fee arrangements are effective incentives, their use is not without problems. A problem common to all award fee arrangements is the high cost of administration. Award fee administration requires the appointment of award fee evaluation boards and performance monitors who must stay familiar with the contractor’s ongoing performance. If an agency is not willing and able to devote the appropriate assets to the administration of the award fee throughout contract performance, the use of an award fee arrangement would be a mistake.

While award fee incentives are effective when administered properly, this does not always happen. A common problem is late payment of the award fee. Care must be taken to ensure that the incentivized areas are evaluated and the award fee amount is determined promptly, coupled with a procedure that ensures prompt payment to the contractor. Incentives do not work well with contractors who are paid late.

Another potential problem is the inflation of award fee payments. These payments are based on subjective evaluations; in long-term contracts when the contractor performs well and pleases the government evaluators, there may be a tendency to upgrade the contractor’s performance to a higher level or to fail to downgrade the contractor if the quality of the contractor’s performance deteriorates in a given performance period. This tends to negate the effect of the incentive because the contractor will get used to being paid more for less effort.

Given the minimal value of the formula-type incentives, award incentives, despite the potential problems, are still the most effective incentive for PBSC contracts. This is because the administrative effort necessary to monitor a PBSC contract mirrors that needed to administer an award incentive. Thus there would be little, if any, added administrative cost. The other potential problems can be handled through effective high-level contract management.

The only drawback to using award incentives for PBSC is that they are generally not viable for contracts of low dollar value because they do not generate sufficient award funds to motivate the contractor to improve performance. However, even in the lower-value service contracts, there is enough value in the feedback inherent in award arrangements to at least warrant consideration of using of this type of incentive.

The advantages of award fee contracting accrue primarily to the government and are applicable only if the government manages the contract properly, that is, uses appropriate award fee evaluation criteria, uses conversion techniques (from evaluation points to award fee dollars) that appropriately reward contractor performance, monitors the contract properly, and ensures that award fee amounts are paid promptly.

Award Term Incentives

Award term incentives “reward” a contractor for excellent performance with an extension of the contract term instead of an additional fee. Satisfactory performance results in no change in the contract term, and unsatisfactory performance results in a reduction of the current contract term.7

Award term incentives are not contract options; the exercise of an option is a unilateral government right to be exercised solely at the government’s discretion. Contractors do not have a “right” to an option. An award term incentive provides the contractor with a legal entitlement to a contract extension when all conditions are met (i.e., the contractor has provided excellent performance, the government has a continuing need for the services and has sufficient funds available, and the contractor has met any other specific conditions set forth in the contract). When these conditions are met, the government must either extend the contract term or terminate the contract.

Generally, award term contract arrangements work like award fee contract arrangements. The process is established in an award term plan that is implemented by a contract clause. The clause and plan should establish:

The organization and responsibilities of the personnel who will conduct the award term evaluation.

When and how the evaluations will be conducted.

The evaluation criteria to be used.

The basis for either a contract term extension or reduction, depending on the quality of the contractor’s performance.

How the evaluation criteria or other parts of the plan can be changed.

How disputes over the process will be handled. It should be noted that the DoD Guidebook for Performance-Based Services Acquisition indicates that the government’s decisions on award term are not subject to dispute. This might not be valid, however, because there are court rulings8 to the effect that similar statements (that the contractor cannot dispute award fee determinations) are not valid. Therefore, award term clauses should provide for a disputes process.

There are no published policies or procedures on the use of award term incentives and there have not been any significant rulings by GAO or the federal courts on this concept. Several problems immediately come to mind:

1. FAR Part 6 requires full and open competition when acquiring goods or services. Would award term contract extensions, which could extend the contract term for five to ten years, violate the requirement for full and open competition?

2. While award term incentives are technically not options, to what extent will the concepts set forth in FAR subpart 17.2—Options be applied to award term? For example, solicitations including options must indicate the entire possible contract term, and options must be priced and the option prices evaluated prior to contract award. How the options concepts will apply to award term has yet to be decided. Pricing will certainly be a problem with award term, particularly with respect to the out years when they could extend well beyond five years. Generally, with the exception of economic price adjustment clauses, contract prices cannot be renegotiated during the term of the contract unless the contract has been modified, and then only with respect to the modification itself.

3. While award term will provide for long-term relationships with contractors who continue to perform in an excellent manner, are such relationships necessarily a good thing? In theory, long-term contractual relationships can result in increased efficiency and effectiveness as the contractor gains familiarity with the government project and the government processes and becomes more of a partner in the project. Government project managers would prefer to have a continuing relationship because changing contractors is disruptive and could have an adverse effect on the program.

Such long-term relationships, however, can become incestuous. Service contracts require close cooperation between the government and contractor personnel. Over time these relationships can become personal, and the objectivity of government evaluators can become questionable. If the contractor is not performing poorly, there may be a tendency to rate the contractor’s performance higher than really warranted. This has been a problem with award fee contracts (consistently high award fee payments that do not necessarily reflect actual performance) and could become a problem with award term contracts.

4. Another problem would be how to evaluate excellent performance over a long term. How often can a contractor perform in an excellent manner before such performance becomes standard? How long can a contractor improve upon its performance before it becomes impossible to make any further improvement? If satisfactory performance brings no further contract term extensions, award term could self-destruct over a period of time.

5. What if the government or the contractor wants to get out of the contract? Long-term contractual relationships can become a problem for both the government and the contractor. The government always has the option to unilaterally terminate for convenience, but contractors generally do not have the right to quit a contract when it is no longer to their advantage to continue performance. Business situations can change over time, and what was a reasonable arrangement could become less advantageous over a long term. It would probably be necessary to provide the contractor a contractual way out of the contract. Otherwise contractors who want out of an award term contract would have to reduce their performance to satisfactory, which does not extend the term of the contract, or to unsatisfactory, which acts to reduce the term of the contract. In such instances, the award term would turn out to be a disincentive to excellent performance.

Before attempting to make an award term contract, you should consult with agencies that have awarded such contracts, such as the Air Force, NASA, and GSA. There are also a number of publications that address award term contracting. Some of these are:

“Award Term: The Newest Incentive,” by Vernon J. Edwards, October 30, 2000, published in the February 2001 issue of Contract Management magazine, page 44. This article can also be accessed at http://www.wifcon.com/anal/analaterm.htm (accessed February 2012).

“The Award Term Incentive: A Status Report,” by Vernon J. Edwards, February 2000, published in the February 2002 issue of Contract Management magazine, page 22. This article can also be accessed at http://www.wifcon.com/anal/analaterm2.htm (accessed February 2012).

Guidebook for Performance-Based Services Acquisition (PBSA) in the Department of Defense, December 2000, page 13 and Appendix I. This publication can be accessed at http://www.acq.osd.mil/dpap/Docs/pbsaguide010201.pdf (accessed February 2012).

AFMC Award-Fee and Award Term Guide, Department of the Air Force, November 2000. This publication can be accessed at https://www.acquisition.gov/comp/seven_steps/library/AFMCaward-fee-guide.doc (accessed February 2012).

Should Incentives Be Used in PBSC Contracts?

If the coverage in this section on incentives appears to be negative, that is because since the 1960s studies on cost incentives (FPI and CPIF contracts) have shown that they have little or no effect on a contractor’s performance. If cost incentives do not work, it is not likely that performance incentives will have a material effect on contract performance. There does not appear to be much research on the effect of performance incentives, probably because of the complexity of multiple incentive contracts (the FAR requires a cost incentive in multiple incentive contracts) and the fact that contract changes generally erode the relationships between the various incentive elements, making it difficult to determine the effect of the incentive on contractor performance under FPI and CPIF contracts.

There are, however, published accounts9 of the successful use of multiple incentives in service contracts. In most cases such contracts are large dollar value, multi-tasked efforts, and the contracts used a combination of contract types to achieve their goals. The key to success was careful preparation and effective contract management.

As noted earlier, award fee incentives are probably the most effective incentive for PBSC contracts. Effective management of award fee incentives requires continuing communication between the government and the contractor, as does the management of a PBSC contract. Because the resources necessary to manage an award fee contract mirror those required for the management of a PBSC contract, the administration costs are not increased. However, award fee incentives will work only if structured and administered properly.

Contracting officers are not limited to those incentive arrangements set forth in the FAR. Other incentive arrangements, if they make sense and do not violate any prohibitions set forth in law or regulation, may be used. A word of caution, however: FAR 16.402-4 states that “all multiple-incentive contracts must include a cost incentive (or constraint) that operates to preclude rewarding a contractor for superior technical performance or delivery results when the cost of those results outweigh their value to the Government.”

Award term is an example of an innovative incentive concept that is not covered by the FAR, and since it is not a multiple-incentive arrangement, a specific cost incentive is not required. It should be noted, however, that cost control should be a primary evaluation criteria in the performance evaluation of an award term contract.

Service contracts tend to be long term, and this could be a problem with respect to the use of incentives. One of the primary purposes of an incentive is to motivate the contractor to a desired level of performance (i.e., encourage contractors to improve their performance). But at what point does this end? How should incentives be applied in the long term? If the basis for the incentive is satisfactory performance and the contractor is paid a bonus for performance above satisfactory, does a contractor who routinely performs at a level above satisfactory continue to receive the bonus over the term of the contract? If the incentive is supposed to be used to encourage improved performance, shouldn’t the bar be raised for the continuing performance (i.e., at some point the contractor’s routinely excellent performance would be considered to be satisfactory in order to encourage incrementally better performance)?

On the other hand, if the bar is raised and the contractor is not paid the continuing bonus, this would, in effect, be penalizing the contractor for its excellent work. There is a limit to how much performance can be improved. There is also a cost to the contractor for improved performance, such as training of its personnel in new methodology and research to find ways to improve performance. Generally, these are acceptable costs if they serve to improve the contractor’s competitive position and bring in new business. But on the individual contract level, how long will the incentive be effective if each year the contractor is expected to incrementally improve its performance to earn the incentive?

The practical solution would be to keep the definition of satisfactory performance stable and to, in effect, pay the contractor extra for its continuing excellent performance. This tacitly recognizes that the contractor is performing at a level higher than anticipated and therefore is earning the incentive amount, even if there are no longer any incremental improvements in contract performance. The incentive is now operating to encourage the contractor to continue its excellent performance rather than improve its performance. Whether the contract is still an “incentive” contract is debatable, but it does get the job done.

Long-term incentive contracts, if not managed well by the government, can become problem contracts. The following is a possible scenario: After several years the contractor’s project manager realizes that further performance improvements are not practicable and continues performance at the same (albeit high) level. Over the next several years, the contractor continues to receive the incentive amounts because the government program personnel are pleased with its performance and routinely give the contractor high grades. Over time, however, the contractor’s performance deteriorates because either: (1) the contractor’s more experienced personnel are transferred to newer projects that need their experience, or (2) the contractor personnel grow complacent because the contract is “safe” and they are not being challenged. It will take some time for the government personnel to react to the deteriorating performance. When they do begin complaining, the contractor changes program personnel and performance begins to improve. Improvements are possible because the bar (for satisfactory performance) has been lowered due to the deteriorated performance, and there is room for improvement—back to the level where further improvements are no longer practicable. And the cycle repeats itself.

This is a possible, but not necessarily probable, scenario for a long-term incentivized service contract. Incentives could be described as follows: Donkeys are not dumb. If you dangle a carrot in front of a donkey’s face, it will not be long until: (1) the donkey grabs the carrot and eats it, or (2) the donkey realizes that it cannot get the carrot and stops trying. Incentives have a shelf life, the duration of which is dependent on the type of services being acquired and any practical limitations on performance improvements. When deciding whether to incentivize a PBSC contract, consideration must be given not only to the type of incentive to use but also to how the term of the contract might affect the effectiveness of the incentive arrangement. This is particularly true of the award term incentive because the contractor must provide “excellent” performance to earn an extended term—how “satisfactory” and “excellent” will be defined in the out years should be a matter of concern.

Deductibles

The term “deductibles” refers to a procedure, used primarily in service contracts, to ensure that the government does not pay for something it does not receive. While technically not an incentive, this process does act as a negative incentive. Deductibles are used to reduce the contract price (or fee) when the required level of services is not provided or does not meet the required quality levels.

In Part 46, Quality Assurance,10 the FAR addresses nonconforming supplies or services, stating: “For services, the contracting officer can consider identifying the value of the individual work requirements or tasks (subdivisions) that may be subject to price or fee reduction. This value may be used to determine an equitable adjustment for nonconforming services.”

Deductibles are developed by determining values for the services to be rendered, usually on a line-item (per performance indicator) basis. This process was discussed in detail in OFPP’s Pamphlet No. 4, A Guide For Writing and Administering Performance Statements of Work for Service Contracts. Figures 3-4 and 3-5 are examples from this pamphlet that illustrate generally how this is done. [NOTE: This pamphlet and OFPP Policy Letter 91-2, Service Contracting, have been rescinded (but still may be available on bookshelves or libraries) because the subject matter has been covered in the FAR and OFPP’s A Guide to Best Practices for Performance-Based Service Contracting. The examples in Figures 3-4 and 3-5 were not included in the newer coverage but are still valid examples of how to develop deductibles.]

The deductible value is often based on payroll costs to reflect the value of each performance indicator. The number of personnel and the associated payroll costs can be determined using government staffing and payroll costs or those of an incumbent contractor. The value of each performance indicator is shown as a percentage reflecting the relationship of the payroll costs of that activity to the total payroll costs. If the services are not rendered, or performance is unsatisfactory, the percentage figure represents the percentage to be applied when calculating how much is to be deducted from the monthly invoice.

FIGURE 3-4:

Deduct Analysis

FIGURE 3-5:

Deducting for Non-Performance

To summarize (since the two examples are not related), the value of each performance indicator is determined based on the relation of the payroll cost of that activity to the total payroll cost. For taxi operations, the value is 19.2%; in the deduct formula, this would be the quality of completed work deduct percentage. The payroll costs are used only to determine a value for the performance indicator. In the deduct formula application, the dollar figure used is the total monthly contract price.

It is not a good idea to use both a deduction schedule and an incentive in the same contract because the application of both can be complicated and lead to problems. The primary problem with combining deductions and incentives is that it would not be proper to reduce the contract price for services not received, or received but not with an acceptable quality, and then make a further reduction for the same reason under the incentive arrangement. If both are used, the deductible should be applied first and then the incentive applied to whatever is left. It would be better to decide early to use either a deductible or an incentive arrangement, but not both.

Another problem with deductibles lies in their application. A common mistake when dealing with a task comprising multiple subtasks is to indicate that a failure to complete one subtask satisfactorily will cause the entire task to be rated as unsatisfactory. For example, in a contract for hospital janitorial services, where a number of different areas were to be cleaned, a failure to clean one area satisfactorily would have resulted in an unsatisfactory rating (and a contract deduction) for all room-cleaning services. The problem was that there were different cleaning standards: sterile for operating rooms, while administrative areas were judged on such factors as ashtrays and waste receptacles emptied. GAO11 ruled that an overall deduction could not be applied in light of the different standards. The application of deductibles must be reasonable and must have a sound and documented basis.

SUMMARY

Developing the PWS, QAP, and incentive structure can get complicated. When examining each task to develop performance indicators, there is a tendency to use every possible factor involved in task performance. It is important to keep the process simple. Only those factors most significant with respect to successful completion of the task should be included. In developing performance standards and AQLs, the standards and deviations should be realistic and should reflect a satisfactory operation rather than a perfect operation.

Every factor used to measure contractor performance must be monitored in accordance with the published surveillance plan. This will significantly affect the number and quality of personnel assigned to contract administration. Once the surveillance plan is published in the QAP, it becomes a contractual requirement on the part of the government. If the government fails to adhere to the plan, the government’s ability to enforce the contract terms will be adversely affected.

A PBSC contract requires a more extensive planning and development effort than that required for a typical service contract using a functional SOW, and sufficient time must be allowed for this effort. A PBSC contract also requires significantly more contract administration effort because the contract must be monitored in accordance with the QAP.

These problems notwithstanding, PBSC offers an opportunity to develop a service contract that explicitly requires the delivery of services of a predetermined quality. PBSC works best when used for services of a continuing nature, where the services can be defined in terms of objective and measurable performance standards and the cost of developing the initial contract can be amortized over a number of contracts.

The difference between PBSC and a service contract using a functional SOW lies primarily in the PWS requirement for specific, measurable performance standards and acceptable quality levels; the use of a QAP to summarize the performance standards and establish the surveillance methods and schedule; and the preference for the use of incentives.

While agency-developed procedures may differ somewhat from this book, the details of how to structure a PWS are not significantly different from those of a functional SOW.

The information set forth in Chapter 5, The SOW Format, and Chapter 6, Common Problems in Writing SOWs, is applicable to both the PWS and the functional SOW. Chapter 4, Using a Statement of Objectives (SOO) and Related Issues, addresses a new concept as a substitute for the use of a PWS.

NOTES

1 FAR 37.601.

2 FAR 37.602(b)(3).

3 FAR 37.601(b)(3).

4 Guidebook for Performance-Based Services Acquisition (PBSA) in the Department of Defense, December 2000. Online at http://www.acq.osd.mil/dpap/Docs/pbsaguide010201.pdf (accessed February 2012).

5 Ibid.

6 For some examples of these studies, see the article “Award Term: The Newest Incentive,” by Vernon J. Edwards, pages 2–4, which can be accessed at http://www.wifcon.com/anal/analaterm.htm (accessed February 2012).

7 For a good discussion of award term contracts, see https://www.acquisition.gov/comp/seven_steps/step5_consider.html (accessed February 2012).

8 See Burnside-Ott Aviation Training Center v. John H. Dalton, Secretary of the Navy, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit No. 96-1227, 2/25/97. Online at http://www.ll.georgetown.edu/federal/judicial/fed/opinions/96opinions/96-1227.html (accessed February 2012).

9 See “Performance-Based Contracting Incentives: Myths, Best Practices, and Innovations,” by Gregory A. Garret, Contract Management, April 2002, and “Strategy-Driven Service Contracting,” by Lyle Eesley, Contract Management, March 2002. See also “A Case for Multiple Incentives,” by Tom Dickinson, Contract Management, February 2001.

10 FAR 46.407(f).

11 Environmental Aseptic Services Administration and Larson Building Care Inc., B-207771, 2/28/83, 83-1 CPD ¶194.