Use of Skills

64 Do You Have a Plan?

Knowing and using the appropriate questions, at the appropriate times, asking the appropriate people, and obtaining what you need in addition to communicating what you want is an extremely difficult job. The objective is to succeed as often as possible, but not to expect success with every interaction. This is a modest objective that takes practice to achieve.

For some managers, the belief that all interactions have been successful is one of the consequences that I have observed in accomplished leaders. In the earlier example where a senior vice president asked a manager to lie to her, her accomplishments over many years had led her to believe that all her interactions and her questions resulted in successful outcomes. For these people, when a business has been particularly successful, habits set in and all of their interactions are viewed as productive. In my opinion, this behavior seems to be a natural consequence of years of good management. However, this often comes to an abrupt halt.

Unanticipated changes in market conditions, unexpected challenges from unlikely competitors, a new business venture, or a change in management in a critical part of the organization may yield problems. The business in our earlier example suffered severely after the interaction where the vice president asked inappropriate questions. In these cases, boards need to step up to the challenge and begin asking questions—different questions from those of senior management.

Accomplishing the modest objective of improving each interaction takes practice. A strategy or plan is the suggested route to take for most formal settings when you will be in a situation where you will be a questioner, interrogator, examiner, detective, interviewer, or inquisitor. This chapter provides insight and guidance into many of the more common management situations.

Managers need to enter business discussions with more than their “wits about them” (if only all managers did have their wits about them). They need a skill set and then some templates on when to recognize a situation that calls for probing, for example, or how to go about testing a new business idea.

A few basic ground rules might help when questions are in order.

General Questioning Strategy for Most Business Settings

- Identify the specific kind of situation you are in.

Is the setting formal? Are people presenting to you as the primary audience or to others, or is this more of an informal discussion? It is a small step but an important one to consider in all settings where you are functioning as a manager. It is equally important to understand whether you, as a manager in this particular setting, are expected to be there in an “inquisitor” role. If you are just visiting, a polite question to demonstrate that you are paying attention is advisable (however, in-depth probes are not).

- Watch carefully for the need to follow up and probe. This is the most neglected area of questioning by managers at all levels.

People say things in meetings that often go unchallenged when there are clear and obvious follow-up questions to be asked. In some cases, the time or the setting is inappropriate.

In one of the marketing jobs I had, we used to prepare and present quarterly reports to senior management. These reviews were designed to familiarize management with the staff rather than to review any aspect of the presentation. Questions were asked to demonstrate interest and to test the ability of the presenters to think on their feet under pressure. These were not the types of reviews where follow-up questioning was appropriate.

That said, however, I have seen people slip into their discussions a couple of key points that they think need to be made, when they can “get away with it.” If you see that happening, you can follow up the next day or at some later, more appropriate time. Just because it was mentioned to senior management during a business review does not mean that it was approved, condoned, or even heard.

In some cases, managers will be presented with information that makes no sense, like “it only appears that we had a revenue decline, but this was due to currency imbalance” or “although the scrap rate is high, we believe we will have it cut by 50 percent by the end of the next quarter.” These kinds of statements need to be followed up.

In the currency-imbalance case, what the speaker really meant was that there was no imbalance. The forecast was way off the mark, and the young manager was taking advantage of an unfavorable change in rate to explain poor contingency planning in the business. The attempt to create some confusion around business performance was cleared up, after the fact, to the disappointment of the manager.

The scrap-rate comment on the surface looks good, but when questions were asked that peeled away the layers of data that backed up this comment made during a management review, it was discovered that the plant was currently scrapping a full 50 percent of finished product, not scrap produced along the production line. In many plants, a considerable amount of scrap is a relatively normal occurrence as a byproduct of the process, but not in this case. A 50 percent reduction in this particular scrap rate still left this business with an unacceptable level of 25 percent scrap at the finished product level.

- Determine a path to take for your questions. For example, follow up for clarification; if unsatisfied, challenge the respondent and probe for details. If necessary, redirect questions back to the main discussion.

This is an intuitive skill for many managers, whereas many others have absolutely no skills in this area at all. For those people who have had good teachers, or who have an intuitive sense of mapping out questioning strategies, this appears obvious. For others, it takes practice.

Managers occasionally get themselves in a situation where they are led down a path the respondent chooses rather than the path dictated by answers to the questions being asked. I have seen them become exasperated by an inability to get the answers they want, or they take the bait, so to speak, and follow a line of questioning that leads away from the original focus. In either case, a successful obfuscation has occurred—not good for business.

A marketing program piloted by a new manager in one region had resulted in a 10 percent growth in the business in just one quarter. This was a huge increase, almost one whole market share point in that particular market. This explanation was accepted by the VP. It never occurred to him to probe into the reasons for this success. All of it came in one contract. Everyone wanted to be a part of the success, so little probing was done beyond the numbers, and no one wanted to stand in the way of what appeared to be a success. When the program was rolled out to more regions, little growth occurred. Success and failure deserve the same level of attention.

To avoid making inappropriate assumptions, consider mapping out some simple redirecting strategies. It can look like a decision-tree map to make it simple.

Q: That is great news. We moved up a share point, but how many new customers ordered, or was there an increase in ordering from existing customers?

You could have had this question in your mind beforehand, or it merely could have come to you during a product-review discussion. In most cases, data is fairly well known before people get into a room or before the person appears for a meeting or even a phone call. In either case, a brief list of what you will do suffices for detailed directions on how to do it.

A: The increase is due to new business.

Q: Good. So, how many new customers?

This is an acceptance of the response showing respect to the person answering while demanding the same in return. The marketing manager, if he were the person answering, would be putting the best face possible on the data. The probing, which was not done in this example, would have saved a lot of time and money for this particular business.

- If your question provokes anger, do not argue. Instead, explain, ask, and redirect.

We have already discussed using a raised voice to communicate anger. Respondent anger or argumentation should be avoided in most circumstances. In many cases, it is an effective way to deflect critical questions. This is common to HR discussions with employees when a sensitive issue is raised, such as attendance.

Q: WHAT DO YOU MEAN I AM NEVER AT MY DESK WHEN YOU CALL? DO YOU KNOW HOW MANY CALLS I GET EVERY DAY? DO YOU HAVE ANY IDEA HOW MUCH CRAP I HAVE TO PUT UP WITH ON THE PHONE?

The person putting up with crap here is the manager, if she lets this conversation run too long. She must maintain focus on the issue. In this case, the employee was being paid to answer the phone in an environment that provided a lot of personal flexibility. The fact that she was using anger to deflect her supervisor’s questions clearly demonstrates the problem. This kind of response is found at all levels of business.

A senior vice president/divisional general manager in a large multinational company, when asked by the CEO to explain a hard-to-believe financial turnaround by one of his business units also responded with anger.

VP: YOU OUGHT TO HAVE PEOPLE IN THESE JOBS YOU TRUST. THE BUSINESS IS DOING WELL. THE MANAGEMENT TEAM HAS DONE A HECKUVA JOB, AND I THINK YOU SHOULD BE CONGRATULATING THEM!

CEO: Thank you, Bert, for a proud defense of your business and your team.

This was a public meeting, and old Bert thought he had gotten away with a masterful performance of deflection, which he had displayed on many occasions. The CEO let others ask the appropriate follow-up questions. Bert later chose an early retirement when an audit, ordered by the CEO, revealed irregularities in a number of financial areas.

- Avoid pursuing unrelated and unimportant details.

An agriculture business had developed a new fishing bait using waste product from one of the manufacturing processes. It had a number of positive environmental attributes. It removed a solid waste problem and turned it into a nonpolluting product that could generate sales from a relatively low investment. It was nontoxic and biodegradable.

After sitting through a two-hour discussion of the technical problems of producing the fishing bait, the business manager simply turned around and said, “So, tell me, do the fish like it?”

If the fish didn’t like the bait, solving all the manufacturing problems would not help the product one bit. As it turned out, the fish were not biting.

- Close an inquiry with converging questions.

This strategy allows the lose ends to either be tied together or recognized as such, setting up future discussions. Unless the discussion is going to be continued, it is suggested that some convergence be the objective of discussions that produce much difference of opinion. Convergence does not mean agreement. It just means that the argument is being brought back to a central point.

Q: How many choices do we have for odd lot materials to list for sale?

Q: Because it appears unlikely we can afford to support the sale of all of those products simultaneously, is there some criteria we can agree on that will establish a priority for accepting and then listing product for sale?

- Keep an open mind.

An open mind is all that can be asked of anyone in any management position in business today.

Q: What do you mean by “I don’t get it”?

A: You don’t. Do you have any idea how we do our jobs in the division? Do you even understand what it takes to compete for promotion and bonuses in this organization? Did you bother to ask any of us before you made your promises to senior management?

And so, the business manager in this case sat through a full three hours of complaining by his staff. She would stop them every once in a while to ask a clarifying question, but other than that, she sat and listened attentively to what was being said.

They were very unhappy with a hands-on manager after having lived through a series of managers who were absentee-leaders. The last two people spent more time on the golf course than they did with the staff. This manager needed to wake up her moribund team and did it by putting forward an aggressive forecast to her management. After the three-hour rant, the team realized that they could do nothing to change any forecast already made. The manager also realized that this team had little motivation for achieving anything other than what they had been doing during the past few years. No one on this staff had received a promotion in level or a substantial bonus for good performance. They were angry, but not with her.

So, after changing the incentives, the business team ended up achieving higher-than-forecast results. They were amply rewarded at year’s end. Had the manager decided to push the plan forward, she never would have learned about the reasons for mediocre performance and would have wrongly concluded that the previous managers had just not put enough effort into the job.

- Do not ask too many questions.

One of my good friends had been a corporate planning director while he was being groomed for a more senior position. Unfortunately, he developed a habit of asking too many questions in every review he attended. He felt it was his duty to expose as many soft spots in the business as possible to improve strategic planning. This did not work well for him. Although he became widely recognized for his insight, he was dropped from further promotional consideration because he simply had not learned when to stop.

Earlier in this text, we discussed the downside of asking too many questions. A person might be able to get away with this once or twice, but not as a regular business practice. If continuous questioning is required, it should be moved off line to a private setting. Then, it is important to maintain focus on asking questions until you get the answers needed and nothing more.

- Listen for the complete answer. Do not interrupt (unless for some egregious error or deception).

This is a common courtesy not always followed by managers, particularly arrogant ones. They appear to behave as if interrupting people is an entitlement. Some of them will continuously badger their employees with questions before they have even had a chance to consider answers to the previous questions. This is both bad manners and bad management.

- Stop when you are finished.

The last rule might seem obvious, but how often have you seen a manager continue to drill into a topic when it is no longer necessary? If you are uncertain about knowing whether you have finished, use a pause or a silent question. People often respond with additional information in these situations if they think it will add to the discussion. If further information isn’t forthcoming, you might be at the end of that particular line of questioning. You can always return later if another issue arises that needs attention.

Managers also often forget to use a question to redirect respondents back to the major topic of discussion. They tend to “order” a return if they remember. A question is much more effective because it requires the conversation to be focused on an answer of interest to the manager rather than a general topic.

The general direction of a discussion may look like this:

Example: Business Plan for a New Market

Q: (Clarification) Do you have a reference for those market-growth projections?

A: The numbers are from an article I read on the web.

Q: (Follow-up) What is the specific reference?

A: An article from the Podunk Journal dated April 1.

Q: (Start to probe) This isn’t good enough. The information is suspect. (Use a negative question to get the point across about how you feel about the reference without the need to have a major discussion.) Isn’t that the “journal for little-known and less-cared-about knowledge?”

A: Yes.

Q: (Still probing) Who was the author?

A: Dr. Adam Smith.

Q: (Still probing) Did you try to corroborate this with any other source?

A: No.

Q: (Converge) Can you find another source after this meeting is over?

A: Yes.

Q: (Redirect) If we accept this projection for the moment, how many market segments shown on your last slide does this represent?

The reason the manager is at this meeting is clear—this is a discussion meeting to vet a new market development plan. It is not a decision-making setting. If it were and the data were as suspect as it is in the example, the manager might move to directly challenge, or even provoke, the respondent. Another option, for a cooler-headed manager, instead of provoking is to use hypothetical questions.

Q: I am very concerned that Dr. Smith’s work might be a little out of date. What if he were wrong by a factor of two? What affect would that have on your projections?

A challenge would look a little different and accomplish another purpose—a performance review.

Q: Adam Smith has been dead now for a couple of centuries. I think his data is a little out of date. What do you think?

This is generally not a good idea unless a person is being particularly recalcitrant.

Specific strategies are made up on the spot. The generalized model is not. These kinds of models are built by stringing together the types of questions mentioned earlier in the book with the questioning platforms described in this chapter.

The premise is that managers should begin by assuming their own ignorance when asking questions rather than banking on what they know. That is the foundation of a solid strategy for asking questions; it is built on what is not known.

Find a Strategy

A strategy is a plan to reach a specific objective. Most questions that come to mind during normal business discourse are part of the more generalized plan of the business—they are part of the process that helps accomplish the tasks to contribute to the goals of the organization. However, it is vital to have a plan when your questions are part of a probe or investigation or for some other more focused purpose.

Explicit strategies are recommended for these situations:

• Conducting a probe

• Following-up questioning

• Evaluating ideas, plans, products, problems

• Investigating a specific situation

• Controlling a discussion

• Asking hard questions

• Finding fatal flaws

List what you expect to learn and a few specific questions that will lead to the required information.

65 Follow-Ups and Probes

Follow-up questioning is a normal part of conversation, and probing strategies should be considered an extension of that approach.

For mistakes in reasoning, analysis, or by omission, good follow-up questions can bring out the cogent details in the normal course of questioning. It is always a good idea to follow up when observing mistakes instead of merely pointing them out. The objective of using follow-up questioning is not to set the record straight; it is to focus on information important to decision making, financial considerations, accounting, or on how business is conducted.

There is so much in business that is based on conjecture that information about markets is usually a view of a constantly moving target. Businesses need to focus forward to move product, improve sales, fix problems, adopt or adapt new technology, and find new opportunities. The process of ensuring accuracy or making certain that the record setting is correct is usually focused on the financial and accounting aspects of the business. Probing questions when the numbers do not add up or when things do not make sense are always important to businesses.

Many extraneous details are unnecessary to follow up on, even if wrong, provided they have no bearing on decision making or on costs or how you do business. However, the glossing over of vital information or even sidestepping important issues is the kind of thing where follow up is necessary.

Manager: Tell me, Mr. Enron, just how did you grow from a start-up business with no revenue in June to $4 billion by the end of the year?

Mr. Enron: We held bake sales until we were able to get enough windmills operating in the North Sea to sell electricity to South America.

Manager: Speaking of baked goods makes me hungry. What are we having for lunch?

Asking about lunch is not a follow-up question, yet this kind of lack of follow-up occurs often. This particular situation should also move quickly from a follow-up phase to a probe. Both kinds of inquiry strategies are discussed in the next two sections.

66 Follow-Up Questions

Follow-up questions continue the discussion in more detail. They can also be used to follow up on events or conversations of previous days, or to raise questions that are more current.

Previous discussions do matter. It is important to keep in mind that conversations are like e-mail messages, except they don’t carry any string with them as they wend their way around people. Follow-up questions can be used in this context, as a way of continuing a discussion, or, more commonly for managers, as a way of gaining a better appreciation of subjects under current discussion.

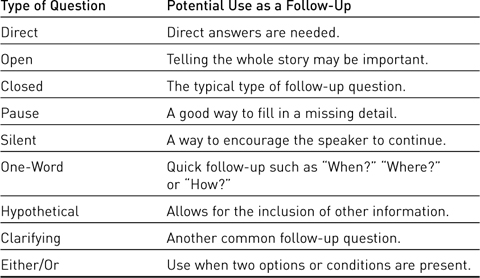

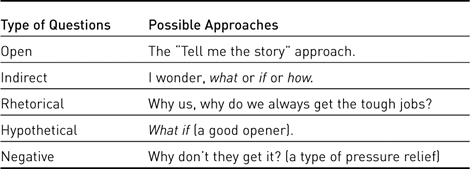

Listed in the following table are general-purpose follow-up questions flexible enough for most occasions. These questions can either be open or closed depending on what the issue is.

For example, if the name of a reference is requested, a short closed question is all that is usually needed. However, if a lot of uncertainty is expressed about a recommended course of action, a more open “What did you mean by that?” inquiry is helpful. This style of questioning allows the story to continue in more detail without introducing bias or passing judgment.

Indirect questions are not very useful as follow-up questions. Negative questions are also less useful than other types of questions. Negative questions have been kept out of this discussion because they raise more issues than they resolve. Management should normally be looking for closure. That is the peculiar and necessary role of business. Negative questions do not necessarily bring the kind of closure usually being sought in normal situations. Although necessary in many contexts, such as in a cross-examination, their use in business tends to politicize many discussions unnecessarily. It is much better for a manager to speak directly to an issue expressing his or her opinions, beliefs, and thoughts. Doing so maintains momentum.

General Purpose Follow-Up Questions28

This is a quick reference list of the kinds of follow-up questions that can be asked in a variety of situations. They represent avenues of additional inquiry that may be open, or offer a manager, board member, or others a mechanism for engaging in discussion without appearing as if there is any ulterior motive. Most managers I have observed generally have habit follow-up questions in addition to whatever habit questions they might acquire as part of their practice of management. By using a different tool—a different question—a new perspective can be gained. It is also equally important for managers, in particular, to demonstrate a number of alternative approaches to asking questions.

What do you mean by that?

What was the result?

In what way?

How did that come about?

Were the conditions different?

How were the conditions different?

When do you expect this to happen?

How often does this occur?

Which way are you leaning?

Can you cite some examples?

How did the glitch you mentioned yesterday affect the operation today?

Then what happened?

What do you mean by that?

Who else?

How much?

When?

Where?

How did that happen?

Have you any alternative theory that will meet the facts?29

What Specific Situations Call for Follow-Up Questions?

A lot of us sit through meetings where, for one reason or another, good follow-up questions are not forthcoming, even when we believe they should be. Consider asking follow-up questions when confronted by any of the situation descriptions outlined here:

• When the assumptions are not clear

Q: What exactly were your assumptions for projecting that this product will capture 20 percent of the market?

Q: Although it appears to be a good idea, what was the basis of this decision?

Q: What do your assumptions have to do with chipmunks?

• When the answer to a previous question is unclear

Q: When you stated that the exchange rate was lower, lower than what?

Q: I am uncertain exactly what you meant. Could you repeat the answer for me?

Q: What did you say again?

Q: Can you explain in more detail?

• When a different question is answered than the one that was asked30

This issue is critical. People often respond to questions with an answer to a different question. Among the reasons people do this are they are attempting to change the subject, redirect the discussion, or avoid an embarrassing answer; or they are unprepared for the issue you have raised and are attempting to deflect it.

Managers who have undergone media training are instructed in how to do this. Executives facing the press are often asked questions publicly that they cannot or would not ever answer. The executive might get away with this in front of a reporter or TV camera, due to the limited amount of on-air time. (Because in these situations, the important issue is to ask the questions.) There is a certain amount of expectation that the answers might not be direct because the agenda of the person being interviewed may be to make a completely different point than the one the reporter wants to make. Although the person might get away with this strategy on TV, no manager should ever fall prey to this distraction when asking questions.

This may also be a signal to start probing. The first step in response to the misdirected answer is to pose a follow-up. If the question is avoided again, start probing. There is always a reason for a misdirected answer. These are not casual errors in discourse.

It isn’t always necessary to restate the question in an interrogative format to return the conversation to the direction you want. A direct reference to the question just asked either by saying you want to readdress the question or by referencing the subject matter is sufficient.

Q: Okay, I understand what you are saying, but I was asking a different question.

Q: That may be, but I still want to know, why should we buy Greenland?

Q: That’s very interesting. However, the question is why did you spend a billion dollars on balloons?

Q: Aside from cockroaches, our interest is in finding the answer to the termite problem.

Note that not all questions sound like interrogatives. The first and last statements above are really questions hiding in comments. They are responses to statements made by others that were evidently not answers to the questions asked.

• To ask for references or for sources of information

There are always varying levels of expertise in any meeting, particularly those on technical subjects. I have heard managers leaving a room mention that some aspects of the subject were unfamiliar to them, and it is in these situations that this question is useful to ask in the open setting.

These kinds of questions seem to occur most often in meetings discussing medical topics. Audiences or meeting participants are very open about their interests in learning more about a particular subject when health is in the balance. Managers, on the other hand, are cast as generalists in many of their assignments, expecting the knowledge that carries the business to be possessed by the staff. The veracity of the data is taken for granted. Also, a general belief pervades most businesses that opinions or assumptions based on inference are normally stated as such. No one likes to be wrong in business because the consequences can be career ending.

So, asking for a reference or a source does not mean that the subject matter is of such extreme interest that there will be follow through—it might mean that the information provided may be worth challenging. Data is often quoted, trends are cited, and government actions referenced in many discussions of importance. Asking for references is not critical in all circumstances, but on occasion, when the facts are surprising or unanticipated given what may have previously been thought, it is always good to ask for the source. In addition, it’s also wise to consider asking for those references that support the prevailing wisdom, too.

Q: Could you provide me with additional references?

Q: I would like to learn more; where can I find a couple of good articles?

• To ask for contacts

Q: Who are your contacts in Kandahar?

Q: Which of the people you mentioned provided this information?

Q: Can you name names?

Q: Who are they?

Q: I want to hear more on the subject of musical cereal; who should we contact?

Q: Are there others who believe as you do?

• If there is a need to reference a previous discussion

Q: Can you explain this in the same way you did yesterday?

Q: Since you mentioned camels before as a primary means of locomotion, just where are you planning to do this market research study you are proposing?

Q: How is this different from our previous discussion?

• When you need familiarity with an issue

Do you have enough familiarity with the subject? Ask yourself the “What if I were asked about this in court?” question to determine whether you know enough.

Q: What else do we need to know before we make a decision?

Q: What questions do we not yet have answers for?

Legal When a reference may be made to a law as a reason for doing or not doing something, managers should consider asking about the law. What is it exactly? How does it affect you and your business in this situation?

Q: What is that law (regulation)?

Q: What are the implications?

Q: Is it possible that we need additional legal resources?

Q: How certain are you?

Regulatory The same issue applies here as with a law.

Q: What are the regulations, the agency, and the ramification of following or not following the regulation?

Q: Are there any other regulatory agencies that have jurisdiction here?

Q: How do we manage our compliance?

Q: How is it that our Pango Pango manufacturing plant is regulated by the city council of Podunck?

Economic and financial If you are unaware of what “generally accepted accounting practices” are, the next time the phrase is used, ask. As we have seen in the popular press in articles about many accounting practices of large corporations, this phrase has been used to cover practices that may be generally acceptable—acceptable enough to land managers in jail.

Q: What do you mean by “generally accepted accounting practices”?

Q: What does this apply to?

Q: How will this affect us?

Q: Who is the guy Adam Smith you keep referring to?

• Data is inconclusive

Q: How soon will we have a better idea about the data?

Q: Are there any other tests that should be done?

Q: Should additional market research be considered?

Q: How can we find the data we need?

An equipment manufacturer was about six to nine months late in getting a product to market—well behind its competitors. Business management wanted to offer the equipment for sale early, before the product was actually ready. So, they asked their attorney if they could take contract orders for delivery at a later date. “No” was the answer. Follow-up questions were not asked, and the attorney was not invited to the business team meeting to explain her answer.

Two months later, as the product team was making plans for attending a trade show—a show where the competition was introducing new products and they would have none—the marketing group decided to hold a meeting and invited the attorney. She explained that, although contracts should be avoided, in her opinion, customers could reserve product customized for their specific application in advance.

At the trade show, with only a model mock-up of the product, the company was able to interest enough customers that they ended up leading the market in new product orders when the product was released.

Follow-up questions should be asked whenever all information necessary for effective decision making is lacking clarity or when all participants have not had a chance to express themselves.

67 Probing Strategies

Probing may be defined as aggressive follow-up questioning. However, you are not necessarily just interested in keeping a continuous line of discussion going. Probes are used to look for something other than what the discussion, the paper, or the message has provided. You probe when you encounter potential deceit, defensive behavior, half-truths, challenges, misdirected answers, dead experts, and any number of other conditions likely to occur.

Remember the manager who asked questions with the answers in them, and then argued when his staff tried to tell him he was wrong? I saw him in action off and on for about two years. Not once did I ever see him probe any topic. Even if he disagreed with the information presented to him, he dismissed it as “irrelevant” or just plain wrong. Probe to avoid becoming this myopic.

By the way, his business unit failed and, unfortunately, he was actually promoted to a new position of responsibility where he could ruin another business. He didn’t disappoint.

A complex mix of objectives surrounds probes. The reason a business manager is doing a probe in the first place, rather than asking simple follow-up questions, is to move the discussion from a straightforward inquiry to an investigation.

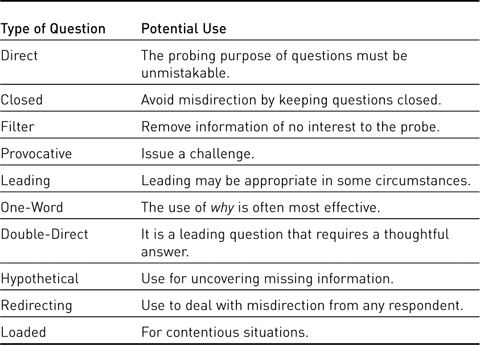

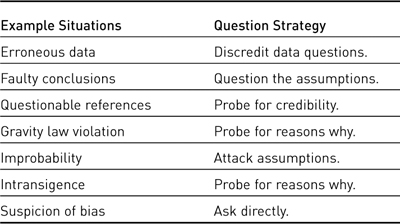

Table . Questions Best Suited for Probes

Launching a General Probe

This list represents launch questions—the road into your pursuit. They are general enough in nature to fit a wide array of circumstances. Probing generally takes longer than following up. For example, when dead experts are used as resources for a business case, you not only need to find living experts, but the manager also needs to understand why the dead experts were cited in the first place.

A continuous series of follow-up questions constitutes an exercise in probing. It can be relentless. The questioning can change directions, and it can be discontinuous if the manager feels that the respondents may be disingenuous in any way.

Who else can we check with?

Do you know where to get additional information? Specifically where? And what does it say?

Why was this particular expert chosen?

Who else uses this...relies on this expert?

Why?

What do you mean by that?

Is there anything else we should be aware of?

What else? Do you have a list of concerns?

Specifically, what should we be concerned with and why?

Is there anything about this that keeps you up at night? (A habit question of an old boss of mine and a good one, too. He had a number of different versions, but he used it to elicit many issues that had not been mentioned in “regular” discussions.)

How can you be certain?

What can we not rule out? Why?

The purposes of probing are varied. Probes are conducted, for example, to determine the credibility of a speaker, the importance of an issue, factual details that have been ignored, or because of a gut instinct about needing more and different kinds of information—searching for something other than what is being presented or discussed with you. Probes are suggested when the situation calls for it. Here are some of those situations when probing is advisable.

When Do You Need to Launch a Probe?

• Violates the laws of gravity

In an earlier example, the growth of a business from zero dollars in revenue to $4 billion in six months “goes against gravity,” as an old colleague of mine liked to say. Common sense tells us that this type of growth is so improbable that it approaches impossibility. If this kind of growth were to occur without an acquisition, you had better get out of the way for an investigation.

Q: Why did you forecast everyone in the world buying one of these?

Q: It was quite windy that day, but how likely is it that the wind caused the coffee to spill inside the building and all over the server?

Q: Dr. Deleon, how do you know you discovered the fountain of youth formula? What evidence do you have? Who else has tested this? What were their results? What do you mean they are now too young to answer?

Dead experts are a dead giveaway that probing for better references is needed. If an expert whose knowledge is critical to whatever business case it at hand is unavailable for a period of time that exceeds your decision-making timeframe, probe for another expert.

Q: Who, other than Adam Smith, can we contact on this theory?

Q: Why is it the only expert in the world on this is in Antarctica when we need her?

Q: Yes, jail is a difficult place to hold a meeting, but another year seems a bit longer than we can afford to wait, doesn’t it?

Q: Who did you pay for this information? How much? Did you get bids from other providers? Who and how much?

• When the respondent continues to ignore a follow-up question and answers a different issue

If this happens, move from follow-up to probe. There is always a reason for this strategy by respondents. Your objective when you shift to probing is to avoid being judgmental. Just because the behavior before you may indicate a problem does not necessarily mean that there is one. Maintaining objectivity until you get all the facts you need is important to the questioning process.

A direct inquiry approach is best. It avoids wasting time. A direct approach also pays off in the future. You are less likely to be faced with misdirection answers from others.

One additional point is worth noting here. You can change your style from a facilitative (kindly) management approach to a more control-oriented or prosecutorial manner (a more adversarial managerial style). The person knows exactly what it is he or she has done, and you must indicate that you want answers. Obfuscation is for politicians and diplomats, not for businesses.

Don’t take the bait by following this rabbit down the hole. Persons good at this strategy will usually issue an enticement in a misdirected answer; it’s likely to be some detail that is well known to be of critical interest to the inquisitor. I have seen managers fall prey to this and realize hours later that they didn’t get the answer to the question they had really asked.

I saw a regional sales manager practice this with his VP of sales. The manager had arrived at the home office just in time to attend a meeting where his interest was a lack of proper accounting of about “a hundred thousand dollars.”

VP sales: Could you review those numbers again for me, Al?

Regional manager: They bother you, too? You know another thing that is an even bigger concern to me is the Simpson’s. They are the largest customer in the country, and we just learned yesterday that they are considering canceling our agreement. Is there any other incentive package we can offer?

How could the VP not return to his original line of questioning? Easy. The Simpson account was huge, well over 20 percent of U.S. sales. Although he might have been able to see through the ruse, he was unable to resist the possibility of the reality of a problem with this account. It could be that the VP of sales was implicitly going along with this misdirection. Asking tough questions of the people you work with every day is often difficult. This is particularly true when you have known them for many years. There is no way to know.

A routine audit of the books disclosed serious accounting irregularities in the preceding case. A change in regional management cleared up the problems and wizened the VP of sales.

The suggestion for responding to misdirection strategies is to maintain focus and keep your probes direct.

Q: Did you understand my question?

Q: Why are you answering a different question than the one I asked?

Q: What makes this information relevant to what I am asking?

Q: Can you repeat what it is I am asking?

Q: How can I be clearer about what it is I am looking for?

Q: What is it about my question that you don’t understand?

Q: Yes, that’s a concern for me, too, but how much did you say you spent?

Q: We will cover that if time permits, but let’s return to my question. What is your answer?

Q: Why are you having a problem answering the question?

• When the answer is incomplete

This, too, could be an attempt at a subtle strategy for avoiding the question. I have seen this happen in meetings with CEOs, for example, when the respondent knows that the time is limited and tries to avoid completely disclosing details of an issue.

Q: Yes, I’m glad that the mess is cleaned up, but I need to know the whole story. Just how did the chipmunks get into the clean room to begin with?

Q: Your data does show that all the sinks we sell are of the best quality, but I need the whole question answered—what is the quality of all the sinks we manufacture? We scrap how many? How long do you think we can remain in business with that rate? What’s being done? What’s the plan? Who’s responsible for implementing it?

These questions reflect an actual situation. A business manager had successfully dodged his VP and the CEO on this issue for years. Literally half of their product line ended up in the scrap heap, but the margins on the finished product were so high that no one paid a great deal of attention. They sold into the luxury end of a market, and no one ever mentioned the scrap rate. This lasted until competitive pressures forced attention to the problem. The business eventually solved the problem and fixed the product line but sacrificed earnings to overcome years of inattention.

Q: I know everybody here liked the ad campaign, but I wanted to know how it tested with consumers? What are the results from market research studies? You did do market research studies with real customers, didn’t you?

By the way, a manager’s voice that goes up at the end is likely to get a more open response.

• Conflicting information, discrepancies, factual errors

A CEO whom I watched in action had a very effective method for dealing with conflicting information. He would state the discrepancy. This is an effective approach because not all discrepant information about a subject is coming from the same person. Information often arrives from a number of different sources, and it makes a better-understood query to state the conflict to the person being questioned.

Q: Joe, the message from your team yesterday was that the project would be ready on time. However, today you have just indicated that a delay is likely. Can you explain the difference?

Q: How could we go from 3 possible reasons for the problem to 11?

Q: Either the duck got into the copy machine all by itself as you suggest, or as Wilson explained, someone put it in there. Which is it?

• Red herrings

When an answer is irrelevant, it’s time to probe. Once again, avoid taking the bait by pursuing the subject, but acknowledge the lack of relevance.

Q: Yes, branches are falling from the trees due to the drought, but why have our sales have been dropping like those branches?

Q: How did a herring get into the last batch of paint? It’s unimportant what color it was.

• Equivocates

Equivocating is the use of words with multiple meanings. This can allow a person to take a position on either side of an issue. Also included in this category of signals that scream “probe now” are behaviors characterized by beating around the bush, waffling, fudging, and stalling. Straight questions, once again, may provide assistance.

Q: We all know that potatoes contain healthful substances and that chicken fat does taste good. Nevertheless, can you explain how much of this healthful food aspect is lost when the potatoes are deep fried in the chicken fat?

Q: Even though the regulation is there for a good reason, and you are correct, we need to document our decision in either case, but we need a specific recommendation on whether we file a new application. What data do you have? What studies need to be done? How quickly can these be done? Who will do them? Is there a reason for your hesitancy?

• Lacking facts, or lack of evidence to support the claims made in answer to your question

Q: Where exactly will this 1,000-store mall be opening?

Q: Why was our data submission to the FDA rejected?

Q: What do we not know about this project that we should known?

• Answers that reflects wishful thinking

When the answers to your questions include a lot of “We hope so,” “We wish it would be,” and “We are encouraged by signs,” consider probing. Do this if for no other reason than to avoid the fate that Ben Franklin ascribed to those who engage in this kind of thinking when he said, “He that lives on hope, dies fasting.”

Q: Could you define what you mean by hope?

Q: What data do you have to support your wish?

Q: How much faith are you putting in “hope” and how much data is available to support that? Who supplied this data? What are their interests in this project?

• Constant use of hyperbole

Q: When you answered that we will get a billion customers overnight, exactly how many customers do you have in your forecast for the end of the year?

Q: Although we appreciate the expression that the new drug will change the way the world thinks about medicine, exactly how will this happen?

• Airtight answers

Probing is also recommended when answers to all questions are closed ended, meaning that there are no potential problems, concerns, or issues to worry about.

Q: Is there anything about the project that keeps you up at night?

Q: What if something were to go wrong? How could we explain it?

Q: I understand that there is no scientific way possible for our fertilizer to smell, but what would have to happen for an odor to be present? How much of the state would we have to evacuate?

Q: Even though you dismiss the possibility, is there a chance that any of us could go to jail? What would have to happen? Give me a list of issues that could precipitate an investigation?

Q: How solid are your projections? Are you willing to bet your bonus?

• The “two false options” gambit

In some rare instances, particularly when a business is looking for someone to blame for a problem, a choice is set up for the manager. The manager is presented with a choice of selecting between two options, both of which are false.

In one particular case, a product complaint had come from a very influential customer, and the service representative, desiring desperately to avoid any possibility of blame, offered his manager two possible explanations for the problem.

“Either manufacturing hooked up the power cables to the phone jack or the customer plugged the unit into a DC line.” There is no way a manager should accept either of these as options without probing around the problem just a little.

Q: What other alternatives are there, and don’t tell me that there aren’t any?

Q: How many times has either of those occurred?

Q: What conditions would cause us to look at these options?

Q: Pins and bullets both have the capability of puncturing balloons, but what do you really think punctured the balloon at 25,000 feet?

• Begging the question

When the reason in support of the answer is produced within the answer itself—when a conclusion is assumed without proof—it’s time to probe a little. Once again, the best approach I have seen is to state what it is the respondent has identified as the answer, and then probe the part of the answer that is unsubstantiated.

Q: Your answer is correct; grass can and does turn brown in August in that part of the world because of drought. What evidence do you have that it was not our fertilizer that caused the problem?

Q: Baldness occurs all the time, but not all at once. What is in our product that could have possibly caused 10,000 people to go bald in 2 days?

• Gut instinct

Follow your gut. It might not lead to any particular problem or issue of concern, but it’s worth developing any line of questioning whenever a feeling of uncertainty, suspicion, or inquisitiveness comes along.

Probes are important to think about whenever you think about following up on answers you are dissatisfied with.

68 Does the Manager Need to Control the Conversation?

Attorneys use questions to control testimony. Managers can also use this method of control, but under specific circumstances. The conversation-control strategy requires that a series of questions be prepared, preferably in advance if possible. If not, then at least you need to be a question or two ahead of the conversation as it’s taking place. Without a series of related questions, many conversations may get out of hand.

A manager, to control her team of unruly engineers, had a long list of questions she would resort to whenever her meetings got out of control—which happened quite regularly. It seemed that the electrical and software engineers were constantly haranguing the mechanical engineers. This conflict resulted in furniture tossing.

This was a new business start-up operation in an old warehouse that had been converted into a kind of service center. The furniture was plastic lawn stuff, and most of it had been damaged in some way long before the arrival of this social experiment. However real the anger appeared to be, no one was ever hit by a chair. Tables were also overturned, but this was the routine way in which the meeting was brought to a close.

Someone would say: Well fine! If that’s the way it’s gonna be....

The folding conference table, which looked as if it had been left by a catering service too fearful of returning to retrieve it, would then be pushed over. This signaled the end of the intellectual interchange. The discussion inevitably would turn to lunch as the group left the room.

The table-toppling behavior was tolerated by the manager because of the creative nature of this particular combination of people with specialized talent and problem-solving skills. She would sit at a desk at the head of the room and fire off questions as if the mayhem in front of her wasn’t happening, but she knew her team. They really were interested in answering the questions, and this is why all the furniture tossing never caused injury or damage.

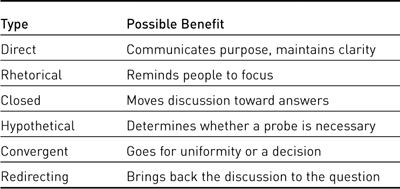

Control strategies are useful under these varying conditions:

• To establish order with an unruly group

• To deal with continuity problems and the difficulty of staying on subject

• To drive for decision or consensus—when a group or team is not moving

• To meet time constraints

• To obtain all information if the person or group will become unavailable

• To launch probes

• To examine data before moving on

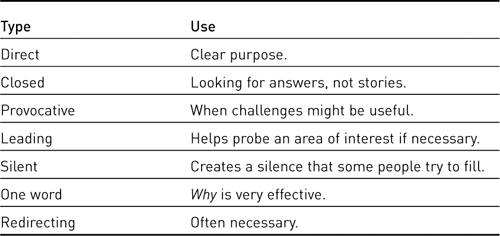

Table . Questions to Use When Employing Control Strategies

Always look for a method whenever you are confronted with madness.

69 Strategies for Asking Tough Questions

A tough question is one that makes the respondent uncomfortable. Some managers find it difficult to ask these questions. This isn’t good for the business. What happens in these circumstances? The business suffers. A mistake or even a deception may continue unabated.

When asked, these questions are often taken personally—because they are personal. A question is being asked of a person to knowingly cause that person discomfort. All of us recognize this and take it personally. It’s a natural response. Therefore, the first order of business for the manager is to remember this: When you have to ask a hard question, try to remember it’s “just business.”

I have had to ask tough questions of employees who suffered from addiction, were suspected of stealing, were accused of sexual harassment, and ones who had a host of other serious problems. These are outside the purview of this book. When a legal issue arises, you need the advice of professionals before taking action—if you have a chance. If you are caught by surprise, as I was on one occasion, you might choose to use the strategy outlined for surprises that follows the “tough” question discussion.

Employing a prosecutorial approach to asking might be necessary under a variety of circumstances. A probe may be necessary. Probes take you off the path you are on, whereas these questions help retain the initial focus of the discussion by asking the question needed and then moving on. If you discover a more serious situation is evolving, start your probe.

Good preparation or familiarity with both the respondents and the subject matter is required; otherwise, your strategy could come unraveled.

Table . When to Employ Tough-Question Strategies

There is a risk of damaging relationships when hard-line questions are levied in a discussion. Their use represents a calculated risk for the manager. This strategy requires that the manager has a good working knowledge of the participants.

Q: Jane, why should I believe that your division has $1 million in earnings when the total revenue of the company is only $1 million?

Questions that target fabrication or questionable data do have a downside. They’re relatively transparent unless the manager is extremely skillful. They could communicate lack of confidence in people who might not have realized there were problems with their data.

I have seen managers who trust no one, and their questions always indicate this type of an approach. No one takes the inquiry too personally under those circumstances. That’s the only good news from the lack of trust strategy. The manager garners no trust either. The group converts from a working organization to an armed camp. There are also managers who should perform veracity tests when they don’t. These folks are continually taken advantage of. The business suffers in either of these extremes.

Try any one or more of these approaches before you start to probe for more details. Answers may pop out, making a probe unnecessary:

Who performed this analysis?

Who else has seen this?

Can you provide me with references for that information?

What were the assumptions, and how were they tested?

What did our attorneys have to say about this?

Whom did you speak with?

Would you recommend that I speak with this person because I have an issue with their data?

Would you stake your next pay raise (or bonus) on that? (This tests a lot more than truthfulness.)

What are the assumptions?

Why do you feel this way?

What are your biases in this case?

What is your personal opinion?

Table . Questions Useful in Tough-Question Situations

The surprise that happened to me one afternoon, a few weeks into a new job, was a call from one of our large West Coast accounts. The gentleman on the other end of the phone was so angry he was incoherent. However, I was able to learn that his assistant had been on the receiving end of serious harassment from one of my new staff members. I immediately recalled this person from our California office to the East Coast, which gave me time to get the advice of legal staff and to assemble an appropriate set of questions.

Contracts were not canceled as threatened, nor was court action taken. After a series of questions to the manager, he admitted to the problem and was demoted, reassigned, and required to enter a counseling program. The questions were personal. They elicited ugly responses at first, and it was unpleasant for us both.

70 Mounting Challenges

A number of different types of questions can be used to challenge the person or persons you are addressing. Why do you want to challenge people? Doesn’t this lead to a confrontation?

Yes, although not always. A challenge can be brought forward without causing a confrontation as long as the line of questioning is viewed as a challenge to the substance of what is being presented rather than to the person presenting it. What if questions work well in this type of situation:

What if our competitor produces our product?

What if we had lost money this last quarter?

What if customers refuse to purchase unless we cut prices in half?

What if we need to reduce the number of employees by half?

What if we lose all telecommunications?

What if we are wrong?

What if our assumptions are based on faulty information?

This is a less-confrontational manner to challenge, instead of asking for proof that the respondent is “right,” which I have witnessed on occasion and which turns the session into an inquisition. Asking what if also encourages creative thought. It lets the organization know that the manager is willing to reach outside of the confines of the usual business discussion to listen to new ideas.

What if questions can also be used to shut down discussion and control meetings in a way that discourages rather than encourages debate. A general manager was listening to a presentation from his technology development organization. The research director, after listening to a discussion of their new technology versus that of a competitor, asked, “What if we license their technology and integrate it into our product line?”

“What if cows had wings? We’d all have shit in our eyes,” responded the general manager, immediately shutting down discussion. He didn’t want to hear any new ideas or concepts that were other than what he wanted to hear. And he definitely didn’t want any business assumptions challenged. This had a disastrous effect.

The research director had been hired by the previous GM. It was clear to him from this remark that he was not wanted. After a short stint in the job, the research director went to another company and then hired away the most talented members of the technology organization, much to the detriment of the business.

Use or allow what if challenges as a way of opening up the business to new ideas and showing that people are valued for creativity.

71 Eliciting Dissent

Agreement is not always necessary, nor is it desired in every business setting. People can and should disagree with decisions in a healthy business environment. Managers need to create an atmosphere where responsible dissent is encouraged. Many managers feel they do. However, the problem for a lot of managers is that they are completely unaware of the fact that they may be squelching dissent in spite of their efforts to encourage openness.

One of the nicest, smartest managers I have ever met directed a sales organization for a major industrial supplier of electronic components. His people all said very nice things about him, and by all accounts he was an ideal boss to work for. When he was transferred to run the marketing organization for the same company, he pulled out the old strategic plan, saw some clear holes in it, and developed a draft plan that he circulated for comment. His detailed plan was extremely complete and well thought out. He received no input.

He brought the plan to his VP, who sensed a problem when he asked about responses. He knew his troops well. “No comment” said “big trouble.” He arranged for an out-of-the-office, all-day meeting for the marketing manager and his staff.

Yelling! Two straight hours of yelling at the marketing manager. It was unrelenting. They tore his plan apart, tore his management style apart—tore him a new orifice, as the saying goes. Why? What could he have possibly done to cause this? Nothing.

He had done nothing directly to his organization. He had also done so much that his staff felt there was nothing for them to do. And that’s what caused him the problem. This was a guy who led from his head. He was smart, and he dominated his organization through the use of his intelligence. His thinking and his overwhelming command of information made it nearly impossible for anyone to have a thought of any value. The other problem with his style was that he was a “nice guy.”

People didn’t want to pick on him, so they just agreed with whatever he said and went on about their business. It never occurred to him that this attitude of his, his obsession for completeness and attention to detail, made dissent nearly impossible. Questions are the cure for this condition. When he received no response, he should have gone around and one by one asked people to share their thoughts. It may or may not have resulted in replies, but at least he would have been recognized as having had the courtesy of asking.

Use of why and how questions may elicit dissent:

Why is it important that we accept the decision?

Our time is short. How can we make sure that everyone who has an idea about this has voiced his or her opinion?

Why is no one willing to disagree?

Why do we not have at least three opinions for our course of action?

How could this be done differently?

How many different ways are there?

How can we do this for less?

Why do we do it this way all the time?

Why do we continue to rely on the same suppliers?

How is it that we continually find ourselves in second place?

How would you do this?

Why agree with the plan? If it were perfect, we would be the market leader.

I have uncertainties about the plan I drafted. How could we improve it? What changes do you think would help us?

These types of questions are also on the soft side. They don’t ask “Who disagrees?” or “What’s wrong here?” Employees are hesitant to respond with candor to these kinds of questions unless they happen to be in a very high-trust employment situation. Even then, the answers will be diplomatic because high-trust situations tend to breed collegiality and good nature.

Remember the chair-throwing engineers? Those guys would have no problem telling management what’s wrong. Nor would they even be polite about it.

So, what happened after a whole two hours of yelling at the marketing manager? The guy just sat there and took it. He was shell-shocked. He had absolutely no idea that he was rolling over everyone with his logic, his command of market information, and his business acumen. Sometime during the second hour, his staff started to feel sorry for him. He was, after all, a nice guy just trying to improve the business. So they stopped.

His boss suggested that he take the elements of the plan, put them up on chart pads, and then ask everyone to pitch in and see what they could come up with as a team. The plan remained essentially the same but now included changes that were important to the staff.

Of course, there is also the opposite problem of intentionally quashing debate. I once worked for a manager who just didn’t want to hear any dissent. He basically said this to his team by stopping all debate once he had made a decision on any particular topic. I stumbled upon this in my usual way—I disagreed with him, not realizing his management style.

I was newly assigned to his business at this particular moment, attending my first staff meeting when I blundered into a dispute. I had proposed a new marketing campaign. He didn’t think it wise and prevented any discussion:

Manager: I really don’t like the idea of doing marketing to this market segment. It has been a market area where we have historically done poorly, and I believe it to be a waste of money.

But I blubbered on.

Me: Well, I can understand why you might feel this way. However, we believe that we can significantly improve our market share in this segment by targeting the advertising directly to the potential customers rather than purchasing agents as we have done in the past.

A look of horror now appeared on everyone’s faces. The “throat-slitting” motion was being directed at me by any number of staff members, as was the old “neck-tie hanging” sign. The boss then surprised everyone.

Manager: You know, you may be right. What if we just scaled down the plan? Pick a few customer targets for a pilot study. Do you think that would work?

After we agreed to a small pilot budget of 10 percent of my original budget forecast, the boss turned around to his shocked staff.

Manager: You know, you guys can disagree with me—just not all at once, and not all the time—but you had better do it with a good idea.

Although his last comment contained a little manipulative twist, it worked for a while. Everyone waited to see whether my plan would work, and it did. We increased sales into a market segment that the business had performed poorly in. When I asked for the original budget after the pilot worked, the boss said, “No.” But the rest of the staff was now empowered to push back, from time to time. On the other hand, if my plan hadn’t worked, it was very likely that I would have been transferred out of the division. Not only did he have a low threshold for dissent, he also did not tolerate failure.

If you do not seek dissent, it might seek you out anyway.

72 Are You Prepared for Any Answer? What About a Surprise?

CEO: Earl, can we count on you to reduce the cost of your operations by 20 percent?

Earl: If that’s what you want, you’ll have to do it without me.

CEO: Earl, did you just resign?

Earl: Yes.

The conversation is a short version of a longer story—a true one. No one was prepared for Earl to resign. He was the chief information officer of the corporation. I’m not certain whether Earl was prepared to resign before the discussion had taken place, but I am certain that the CEO was taken by complete surprise. Would you be prepared to deal with this kind of unexpected response?

Most of us are not. Here is a strategy, a plan for handling a surprise by employing a few questions to avoid making statements until you are certain about your response:

• Reset the clock. Ask what questions. Even if the answer was crystal clear, this strategy will reset the clock and allow you to absorb the answer a second time, when it’s no longer a surprise.

Q: What did you mean by that?

Q: What did you say?

Q: Will you repeat that?

Had the CEO reset the clock in the preceding example, Earl might not have resigned. However, the CEO was caught so off guard that his next question was almost a reflex reaction. Earl may or may not have had a change of heart. But, backed into a corner by the follow-up resignation question, he might have felt he had no choice.

• Engage in fact finding. Ask how, what, when, where, who, how much questions. The key step when dealing with surprises is to look for facts that you need to respond appropriately. In the preceding example, no one knew what to do after Earl resigned.

The CEO, an action-oriented person, went on by saying, “I’m sorry you feel that way, Earl, but you do understand the seriousness of our situation.” The CEO went on the offensive. Many people use offense to defend against surprises. Resist this temptation, at least at this point, especially if you do not have all the facts of the situation in front of you. If you do have all the necessary facts, it’s unlikely this is a true surprise.

Q: How did this happen?

Q: What was involved?

Q: Who else should be contacted?

Q: When did it happen?

Q: Where do we need to focus first?

Q: How much was ruined?

Q: How much damage was done?

Q: Was anyone hurt?

Also, as part of this line of questioning, avoid the you word: When did you decide to do this? How did you know it was ruined? Where were you? And so on. This might put the other person on the defensive. You need answers when surprises crop up, not confrontation.

• Examine reasons. Ask why questions. If you are dealing with a personal matter such as in the resignation just discussed, the line of questioning should probably continue in private. There are personal as well as professional reasons why a person might feel compelled to abruptly alter his or her career path. It may be necessary to insulate that person from view until he or she has a chance to explain.

Our CEO in this example didn’t do that; instead, he went on the offense. His reaction may have even hastened Earl’s exit that same day. The company was left with organizational problems and lack-of-succession issues. Worse, other people started to follow Earls’ lead. Look for reasons.

Q: Why do you think you need to do this now?

Q: Why was that path taken?

Q: Why did this happen?

Q: What were people saying before this occurred?

• Draw conclusions for next steps, if any, and move on. These few steps allow for a full discussion of the surprise, providing the manager with the ability to react quickly if necessary, or more thoughtfully if appropriate.

Could a surprise have been avoided if the CEO had asked Earl a different question? Perhaps. Managers are surprised all the time.

My first surprise in a supervisory capacity came to me in the form of a knife against my throat. It wasn’t the first time a knife had been pulled on me while working at the steel mill, but I was very surprised at this move just the same.

Steel mills are tough places to work. The sign at our plant entrance announced the number of man-hours since the last on-the-job fatality. Every job in the mill was potentially personally harmful. Almost every kind of injury imaginable had occurred, from trains running over men working on the tracks to others being burned by molten steel.

Sporadic fighting also occurred, always away from the watchful eyes of supervision. There were shootings, knifings, and beatings with and without tools, plus the general pushing and shoving that might be expected in a schoolyard. The infirmary treated many men who “fell” while working.

I worked in the labor gang—that’s what it was called in the mill. Few of the men had completed high school, and many of them had faced difficulties such as jail time. The men who worked in this gang were tough men for the toughest, riskiest jobs at the mill. I was dubbed the “college kid” after having worked there for a few summers between school years. I always let my beard grow to appear older and menacing.

The labor gang was responsible for the heavy lifting in the mill—we emptied boxcars using sledge hammers, cleaned out slag (waste material from the steel-making process), shoveled fly ash off girders to prevent buildings from collapsing, and cleaned out steel carriers with jackhammers. We did generally whatever it was that needed to be done.

On one particular evening as I was arriving for the overnight shift, I was met at the door to the locker room by the assistant superintendent (AS) who ran the mill at night.

AS: College kid?

Me: Yeah.

AS: You are the “pusher” on the overnight. Jimmy is out sick—might not be back for a while.

AS: Here’s the list of jobs that need to get done—here’s the list of your crew. Get the jobs done before 7.

That was it. This was the extent of my on-the-job training session. A “pusher” was generally a senior worker who worked directly under the foreman as a kind of supervisor whose job it was to push the men, push the work. Pushers were paid an hourly differential for assuming this responsibility.

It was my first night on. I had worked days and evening shifts for a while on the “cold” side of the mill—the place where the metal is rolled out, cut, polished up, and prepared for shipment to customers who turned it into refrigerator cabinets, washers, dryers, cars, and so on. I had been laid off from the mill three weeks earlier, and then, that day, I was called and asked whether I wanted to work overnight—the graveyard shift. So, I reported to the hot side. The money was better than any job I could have even dreamed of doing between semesters.

I called out the names of the crew and passed out the assignments—just like I had seen done on the two other shifts on the cold side. Only one problem: This was not the custom on the overnight shift.

Most of this crew worked two jobs. Jimmy, the current foreman, and all the foremen before him, had adopted a policy of allowing the crew to pick the jobs they wanted and sleep as long as they wanted. The only requirement was that the tasks had to be completed by morning.

I was the only person present in the locker room that night who did not know this. So, I passed out the jobs, turned around, and discovered a very impressive piece of highly polished chromium steel with an extremely sharp edge against my throat.

The mill was known as a place where people did get cut every once in a while. Industrial accidents happened all the time. This was the prelude to an accident.

Everyone else in the room appeared to be preoccupied with important tasks like tying their shoes. My mind immediately went into fact-finding mode.

Quite to my surprise, I heard myself say, “Is there a problem here that I am unaware of?”

“Yeah.”

Great. It worked. Now all I had to do was guess the problem. “So, can you let me in on the problem?”

And so, the voice holding the knife explained how things worked on this shift. How they get their assignments done and then find places to sleep, holding just a few of the tasks undone until right before first shift so that the mill superintendent who arrived at about 6 a.m. every morning could see them working.

Now they all started laughing. Evidently, the night foreman and pushers didn’t get to sleep. Their job was to ride the trains around the yard with the night superintendent and prevent the mill super (the big boss), if he happened to show up, from discovering the sleeping crew. There was no way that the superintendent didn’t know about the napping. It was a game.

So, just laughter, no cutting that night.

Would I have been cut if I didn’t figure a way out? I have no idea. Like I said, the mill was a dangerous place. Although death was remote, I had seen a lot of fights and a lot of blood.

I trust that today’s managers in most corporations are not faced with this kind of dilemma. However, there are parallels elsewhere to this kind of event. Employees may refuse to do the work assigned, or may call in sick on a critical workday, or may confront a manager with any number of creative surprises.

Surprises can come at you from any direction. Be prepared by using questions to help you manage an appropriate response.

73 The Use of Leading Questions

Leading questions are a specific type of trick question that suggest the answer, and they were discussed earlier as a type of question generally to be avoided. They do have a use, however, depending on what it is you are attempting to accomplish.

The manager in a previous example tried to convince the product manager that a new product was ready for market in spite of the fact that it wasn’t. Normally, leading questions are not considered to be beneficial to a business discussion. They are often asked with the intent of trapping the respondent.

Q: So, tell me Mr. Jones, exactly when did you stop robbing banks?

Or they can be used to mislead a respondent to affect the outcome of market research.

Q: Would you choose the limited service of Bank A or the full service of Bank B, which has more locations, longer hours, and free checking?

Of course, I hope no one would ever ask such a skewed question in a legitimate market research survey, but there are many subtle forms of this kind of approach. The signal to the respondent is the use of qualifying words or expressions that appear in the question. Managers ought to avoid asking these kinds of questions in general discussions and hold them off until a time when their use is acceptable.

Leading questions may be used to move down a path to instruct or to develop a clear recognition of options to follow for the business.

For most business settings, a manager will want to form the question carefully; otherwise, respondents will feel manipulated. Before a leading question is asked, there might be a few preliminary questions containing plausible information. Or as in the case of teachers who ask leading questions all the time, the inquisitor is providing a lesson.

In the following example, the manager was not certain whether the appropriate customer support technical call center costs had been incorporated into the budget forecasts for the business. He also wanted to make certain that the information shared among geographically separated call centers was linked. Finally, it was a way of instructing.

A manager can ask leading questions provided that there is clarity in the objective being sought.

Q: I take it that your budget request is complete?

A: Yes.

Q: Then, should we assume the 24x7 staffing coverage plan is ready to be deployed?

Leading questions are the least attractive kinds of questions to use in management settings, but they continue to be part of the repertoire of most managers. The suggestion to managers is to use them sparingly, and only after careful consideration of the objective of the question.

Too often, leading questions are used to trap a respondent in a particular answer.

74 Looking for Reasons

When you ask the why question, you are generally looking for something behind the words you see or hear. If you were a market researcher, vital information about a choice is communicated in the “Why did you choose the red dog?” question, for example. These questions are best employed when looking for reasons, rationale, or decision-making criteria:

What are your reasons for that?

I’m interested in your reasons for that. Can you explain it in more detail?

Why do you support that?

Why do you feel that way?

Why do you think this is the best course of action?

Why did you say that?

Why is this important?

Why don’t our competitors do this?

Why do our competitors do this?