CHAPTER 1

From Out of Your Power to In Your Power

“It is never too late to be who you might have been.”

—George Eliot, pen name of English author Mary Ann Evans

Early in my career, I had tickets to a rock concert in Washington, DC, one of those blockbuster lineups with all your favorite musicians. As the stands were starting to fill, I noticed a cluster of people in the row ahead of mine, and to my surprise I recognized one of them. It was Tipper Gore, wife of then Vice President Al Gore. She was a strong advocate for policies to improve the lives of women and children, and I thought we might have synergy in our missions. Without a moment's hesitation, I marched over to her, reached out to shake her hand, and said, “Hi! I'm Dr. Sharon Melnick. I do psychology research at Harvard Medical School on how parents who grew up in difficult circumstances can have resilience and confidence to break intergenerational cycles …”

Tipper's interest was piqued, and we chatted about our work and about her daughters. Suddenly, she turned to her Chief of Staff and said, “Melissa, could you get Dr. Melnick's contact information? We want to invite her to the White House to share the policy implications of her research.”

On the flight home, I thought about how fortunate I am that from early in my life, starting at about age five, I have known what work I wanted to do in the world. I wanted to help people turn their private suffering into powerful service and make the contribution they're here to make.

This is what I was here for, what I had studied for so long and worked so hard for. Now maybe I had made a connection that would make that dream a reality. I wrote a short description of the research and emailed it to Melissa.

A few weeks later, as I was lacing up my sneakers to go for a run, my phone rings. It was Melissa! She filled me in about Tipper's initiatives helping millions of families around the country, and at a certain point she popped the question, “Will you come down to the White House to share the policy implications of your research?”

My heart raced with nervous excitement imagining how I could make such an impact. So what do you think I said?

Well, of course, I said …

“No.”

I didn't exactly say no; I said, “I'm not sure I know enough yet from the research. Let me get back to you when we know more.” (It's okay, go ahead and gasp.)

Why? I pictured myself sitting around that table at the White House presenting our findings to Tipper and a group of important policy makers. Even though I had won an award for my work, I was convinced that those people would think I wasn't smart enough. So I prioritized what I thought they might think about me over the once‐in‐a‐lifetime contribution I could have made to the lives of millions of families.1 I gave them all the power to determine what impact I could or couldn't make.

Even if I was in my power during other parts of my day, in that moment I was pulled out of my power. Whether its someone else’s behavior or something that gets activated in ourselves, we shift into a state in which our thoughts, emotions, and actions align to disempower us.

If you can think of being in your power as a state you can get out of, then by definition it's a state you can come back into. When you name it, you contain it. You can know when you're in and when you're out.

Returning to this state is inherently within your control even though the catalyzing event may not have been. You want to devote your energies to making this your default state. It crystallizes your intention—there aren't 10 things you have to “work on” in yourself, just one to cultivate.

The phrase “out of your power” also reminds you that you've disconnected from a source of this power within you and outside of you. It's state you get into, it's not you. This will help you have less self‐judgment if your prior approaches haven't worked or if you still react despite your best intentions not to. In this chapter you will learn what puts you into an out‐of‐your‐power state and keeps you there, and what it takes to get back in your power. (As it turns out, I was invited again to present at the White House about 15 years later and said “yes”. As you start to act “in your power”, you magnetize opportunities to you.)

To become more conscious and in command of being in your power, let's first understand its three essential attributes:

- A Sense of Agency

You see yourself as the creator of your life. You think, “I can.”

Life is not happening to you. You maximize what you can control. You always see options, and you are intentional in your choice of responses. You see yourself as responsible for your thoughts, feelings, and actions. You make choices about whether your current situation is right for you—appreciating that you always have a choice. You operate in your stride, without limits or interference.

- A Sense of Sovereignty

You own who you are. You think, “I am.”

You have an inviolable sense of yourself. You write the narrative about yourself and rewrite narratives that have been put on you. You consciously decide what you believe about yourself, you determine whether you are worthy and enough. You are sure of your values, what you stand for, and what you are here for. Though you learn from others, you trust your own counsel rather than outsourcing your opinion of yourself to others, or second‐guess.

What you think, feel, and say all align and inform how you act. You are able to say yes when you genuinely mean it, and say no when you don't. You are able to ask for what you want and speak your truth without fear of reprisal. You're driven by your values, not what other people impose on you or how you're trying to get other people to think of you.

You know how to create the mental and emotional “weather” inside of you and surrounding you. You recover quickly back into your center if you react emotionally. You know inner peace.

You know what you want and enjoy the choices you make for yourself. You know how to fill your own needs, so you don't have to pressure anyone else or make them wrong for not giving you what you need. When others do support and love you, you can take it in and be filled up by it.

- A Sense of Efficacy

Your efforts effect change. You think, “I make an impact.”

Your actions have the desired results. You can act to make your situation better—not only for yourself but for everyone involved. The way you communicate “lands.” You turn a no into a yes. You move others to action.

You can look beyond the finite problem to see infinite possible solutions. You understand all angles in the context, taking into consideration yours and others’ needs, and pursue win‐win solutions. You resolve the underlying problem at root cause. You attach your own goals to the betterment of all.

You know how to get out of bad situations and find or create good new ones. Your approach transcends the current paradigm.

In sum, these three attributes of being in your power characterize being in—and staying in—your flow. These descriptions hint at the vast array of possible things you can control, ways you can manage yourself, and find resolution, no matter the challenges you are facing.

What Happens When You Are Kicked Out of Your Power?

Getting kicked out of your power starts when something happens to emotionally hijack you. Each person experiences this in their own way, ranging from an intense internal alarm to a subtle sensation. Maybe you get a pit in your stomach or constriction in your chest or throat. It might be like a streak of electricity coursing through your veins or conversely, energy draining out of you like rain down the side of a window. Perhaps you want to do a silent scream or maybe you simply notice a blip on your emotional EKG.

After our initial emotional response, our thoughts put us into a mental swirl. Your reaction beelines to your worst insecurities, immediately thinking that others’ actions mean you are not enough or you don't matter. Our minds become noisy as we blame the offending person for what they did wrong and think what they should have done instead. We carry the experience with us into our next meeting, into our family life, and into restless nights. We feel as if the other person or people have all the power to determine how the situation unfolds. And we feel made small.

Then we act. In the heat of the moment, we might react in a defensive tone. We might avoid, such as not sending an email we know we should send. We numb ourselves with food, drink, drugs, or online entertainment binges. We go on the offensive, strategizing how to get one up on the offender by putting them one down. We might vent endlessly to anyone who will listen. Or we might appear as the swan on a lake, displaying calm above the water while full of commotion below the surface.

This describes an acute reaction to an interaction you may have on any given day, but when you have to interact with that person or system over time your response becomes an automatic patterned approach to that important relationship or your life in general (and a natural adaptation can be to dull our emotions to spare ourselves the pain).

You might even hold yourself hostage with self‐doubt when alone with your thoughts (even despite objective evidence you are crushing it). Once this spiraling occurs, you start to develop the sense that the frustrating situation is just the way things are or turn the accusatory lens on yourself: “This is just the way I am.”

You might be quite in your power in some but not other areas of your life. You may know in your mind you are really good at what you do but in your bones you still question yourself. You may have a group of supportive friends and a family who loves you but can't get your manager to see you. You may be a successful entrepreneur, but your children or your partner make you feel disrespected. It confounds you.

We all have the resources within us to make agency, sovereignty, and efficacy our default state so that even when we are pulled out of our power for a time, we can quickly get back in our power. But we also all have response patterns built into our human nature that will put us out of our power and keep us there if we are not intentional.

Three Power Derailers: Overcome Your Hardwiring to Be in Your Power

Human nature sets us up to be kicked out of our power—and stay there—when a situation:

- Seems out of your control;

- Activates an unresolved pattern in you; and

- Is not improved by your attempts to make it better.

We are even hardwired through evolution to have these derailers determine our responses. But once we are aware of them, we can override them. First let's start with an understanding of how these three derailers operate.

We Focus on What We Can't Control

We only get out of our power when the problem seems out of our control. When you focus on what you can't control, you leak your power. Your nervous system's resources are redirected toward monitoring incoming information about any potential threats to physical survival or emotional well‐being.

These threat detection parts of your brain are like a Marine sentry on the lookout 24/7/365. When a threat is perceived, the Marine sentry sounds an alarm to begin problem‐solving to cope with it. Our minds are programmed to focus much more on what we can't control in a threatening situation than what we can. Your attention will naturally be pulled to the ways you feel “done to,” assessing the list of factors out of your control.

We have a built‐in follow‐up response, which allows us to get back into a place of safety within, once we learn that the stimuli in the environment are no longer a threat. But when we focus too intently on what we can't control, our attention loops only on the threat. Then the Marine sentry can't signal it's okay to let our guard down.

Our acute sensitivity to such threats was demonstrated by a study done with college students. They were asked to write about interpersonal situations in which they had power over others, then ones in which others had power over them, and then complete a cognitive task. Even a brief experience of being out of one's power—simply by writing about a situation in which they felt powerless for a few minutes—reduced their sense of agency and what they thought they could control.2

When threatened, the brain also filters all incoming information through one question: “How will this affect me?” The survival mechanism of your brain literally sets you up to take things personally. While in early human evolution the threats we had to be alert to were primarily about our physical safety, David Rock, author of Your Brain at Work, highlights that today threats to our status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness, and fairness (SCARF) are primary.3 We are wired to be social, and we are constantly looking to other people in order to assess how safe we are and how well we are doing. We micro‐track and then interpret other people's behavior. This is especially true if you're in a lower power position; you'll pay greater systematic attention to behavior of the person in the higher power position.4

Over time your brain associates this “How will this affect me?” question with the more general question “What does this mean about me?” This leads us to the second factor that derails us from being in our power: a personal subconscious reaction you have to the perceived threat.

We Act Out of an Unresolved Pattern

When you become stuck out of power, it's because there is a personal “hook” that gives the situation a disproportionate effect on you. Your brain associates the current situation with a prior experience that registered strongly with you emotionally, and you perceive the theme is related or being reenacted in the current situation.

Every human has had some—or far too many—experiences that have caused us to feel powerless. In order to try to control and make sense of it, we tried to explain and assign a meaning to it, which will remain as an unresolved source of fear, pain, or self‐doubt unless actively processed. This is like “kindling” inside of our psyches. Other people's actions, or the circumstances we're in, can act like a match that lights it afire. These are triggers, a painful reminder of similarly themed past experiences. They teleport us into a reexperience of powerlessness.

Our kindling leads us to personalize the situation, making it about issues from our past rather than seeing it objectively in the present. This subconscious process elevates the perceived gravity of the current situation as implying something about who you are, beyond the current specifics. We're often unaware of our kindling because it is embedded deeply in our psyche.

For example, let's say a colleague left you off an email chain for a meeting. If you are in your power, you might approach the colleague to discuss the value you could bring to the meeting or why it would be helpful for you to hear what the attendees discuss, and then ask to be included. But if an unresolved pattern gets triggered, you might instead ruminate about how you've been left out, telling yourself, “I'm not respected,” “I'm not smart enough to be invited to the table,” or “They're trying to marginalize me,” fully convinced that's what objectively transpired.

Even though the specifics of the current scenario might differ markedly from the situations you faced earlier in your life, your mind has connected the current and the past events through a chain of associations. Suddenly, a situation has become a referendum on your worth instead of an everyday interaction among flawed humans.

Then here's the clincher: When our kindling has been alighted and we're stuck out of our power, we often look to involve other people in shoring ourselves up. We'll seek their validation and acknowledgment, try to prove ourselves even more, or vent to seek sympathy. We'll hold back to prevent them from criticizing or rejecting us and wait for their permission to boldly do what we know we should. We'll try to please and be perfect in order to not disappoint them. You give away your power trying to change people and circumstances outside of you in order to fix something that is insecure inside of you.

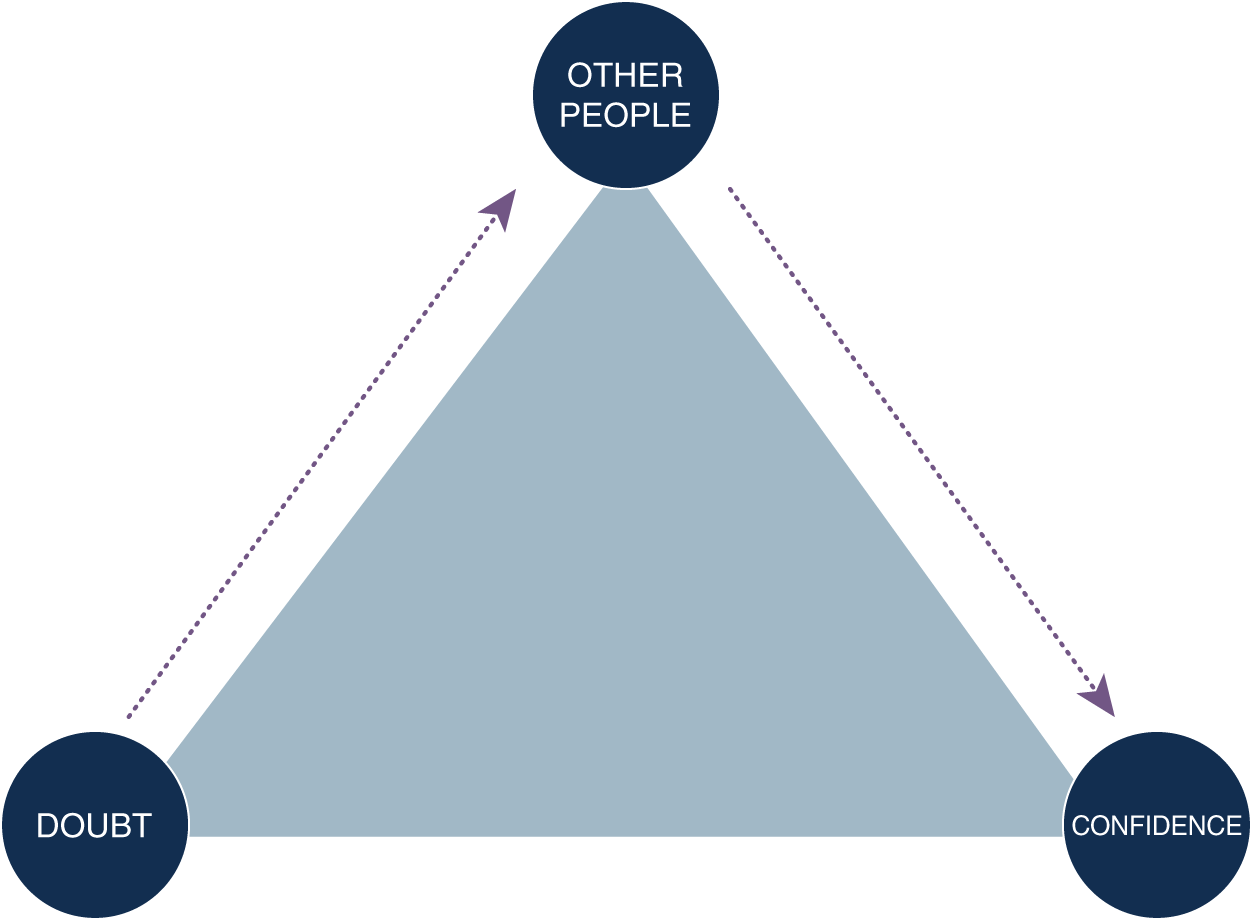

As I introduced in my first book, Success Under Stress, this diagram shows you the visual of how we commonly give our power away. You'll act toward other people (depicted as the arrow up the left‐hand side of the triangle) in order to get other people to act toward you (depicted as the arrow down the right‐hand side of the triangle) so that you can feel secure in yourself. Your time, energy, and attention go toward managing other people's perceptions of you. You outsource your evaluation of yourself to others and overweight their opinions. In short, you involve other people in your own efforts to feel worthy inside. I call these approaches “Indirect.”

With an Indirect approach, it matters how others think and act toward you because you need their input in order to be in your power inside yourself. By setting up a formula where you have to go through others in order to get the thing you need most inside of you, this gives away your power. It sets you up to be the thermometer.

I was the thermometer when I held myself back from an opportunity to make an impact on millions of people's lives because I was worried about what the people around the White House table would think of me.

Indirect behaviors are completely normal. As infants, we are biologically hardwired to seek caring responsiveness from important people in our life. It's the way human babies learn to calm their own nervous system and internalize whether we are worthy of being cared for. Just as we need to breathe in oxygen to grow physically, we must take in “emotional oxygen” from caregivers in order to grow our self‐esteem. As a child grows up, we come to see and know ourselves through the eyes of important others. Our parents’ love and attention, teachers’ evaluation and praise, and peers’ approval and appreciation are the mechanisms by which we come to know ourselves—favorably or not. Similarly, we are hardwired to avoid physical or emotional harm and be afraid of getting “kicked out the tribe.”

In short, important people in our early lives serve as a “secure base,”5 and when we have a responsive caregiver, we go to them in order to be safe, soothed, and assured we matter. From this home base we get the fill‐up we need to go conquer the world.

Indirect behaviors start off as adaptive. Because we have learned to know ourselves through others’ eyes and regulate ourselves through others’ input, many of us continue this approach to feeling secure in ourselves in adulthood. What I discovered in my research at Harvard Medical School is:

What you have been doing right to try to build your sense of power within (i.e., through other people) is the very approach keeping you out of your power now.

If you haven't built the ability to be in your power from your own means, you may keep going to other people to try to get into that state in yourself. And if you don't get the response you need from them, then you're going to try harder to get it from them. It becomes a vicious cycle—you put yourself out of your power and then blame the other person for not being a good source of helping you be in your power.

You can learn to stop yourself from making any specific disempowering situation into a general conclusion that you are not enough or unworthy.

The fix is to Go Direct, which means you source your worthiness from within, independent of others’ evaluations of you. You feel filled by a sense of reward and satisfaction from your contributions. You source your sense of purpose from your Source, however you define it. You become a secure base for yourself to always come home to. Then you have the fill‐up you need, as Jo said, to go out and be the one who raises others.

If you were thinking of this concept in terms of love, Indirect behaviors are like trying to “get love”. Go Direct is “be love.” Go Direct is “feel loveable”—because that you can control. Then it doesn't matter how limited anyone in your personal life or work family is. (To do this, you need to discover what your kindling is and learn to Go Direct, as I will guide you to do in subsequent chapters. Note: There are four specific types of Indirect behaviors, and generic advice can be counterproductive for certain types. Go to www.inyourpowerbook.com to take the full Power Profile assessment for personalized learning.)

My client Susan was able to quickly get back in her power this way after years of being stuck in an out‐of‐power quagmire. A leader in the long‐term disability division of an insurance company, she always had more claims to process than she could get through. Despite backlog being due to the company's bureaucratic processes and challenges in hiring adequate staff, and notwithstanding high praise on her performance reviews, she saw the problem as having to do with her not being enough. She was constantly thinking that she wasn't doing enough and the fire drills were hers to fix. She was constantly monitoring whether she was proving to her boss and colleagues that she was doing enough.

In one exercise together, she had an aha insight. Her mother had been big into volunteering and helping out at food kitchens. Susan had resented all the time her mother spent doing that work, so she avoided doing any such volunteer work. She felt guilty she was not doing enough—not processing enough claims, not giving enough in her community life. Once she made this connection she was able to break the hold that kindling had over her and have a new experience of herself as enough without having to burn herself out taking on more than was humanly possible in the hopes she'd be acknowledged for it.

Often the situation throwing us out of our power does, in itself, present real threats to our goals for ourselves and to our well‐being. Getting back in our power, then, requires strategic problem‐solving that addresses the true issues with effectiveness. This third derailer explains how our brains can work against us taking those approaches.

We Take Flawed Approaches to Trying to Fix the Problem

Our natural emotional stress response can derail our effective problem‐solving, so we overlook the unused power we already have. When out of our power in an emotional state, you can only see a narrow range of options (which may be the same lack of options already thought of, and usually pertain only to how the other person should change). The increased levels of stress hormones in the brain constrict our ability for pattern recognition by shrinking the database searched by the brain.6 Our brains interpret new information in a way that is consistent with the way you recently interpreted this or another situation, so an out‐of‐your‐power cycle can keep you looping on the same understanding of limited options.7 Research on the brains of people in high power and low power positions revealed that the while the goal‐oriented centers of a high‐power persons' brain are active, there is little active goal seeking among the low‐power subjects.8

I often hear from clients, “Well, I said something but …” with the net that they didn't get a cooperative response or even one at all. This was the case for one of my clients, Tara, who was able to turn her situation around after our first session. She was in sales at a Fortune 100 company. She told me she was ready to leave because her manager of six years had systematically denied every request for more resources and better assignments, reserving those for the younger men in the group. It was affecting her income, and she was to the point she had what she termed a “victim mentality.” We agreed that she would give her best shot at influencing her manager, and if that didn't work, we'd pivot to plan B and seek a new job for her to move into.

She had described the manager as being narcissistic and only managing up, which to her meant never being supported because it was all about him. But knowing this about him gave me a great clue about how she might be able to influence him. We carefully scripted her ask, which instead of being about what she wanted would allow him to see how her requests would help him to look good for having granted them.

The next week she emailed to say she met with him and got everything she asked for (and more!) Not only did she stay with the company, but in the subsequent four months she brought in the biggest deal of her career, was promoted, and pocketed an extra $100k in commission. In the position she was promoted to, she was able to improve the process by which deals got assigned and resources were accessed by the sales team, and in that way she was able to raise the rest of the whole sales team up as well.

This is just one small example of the blind spots we have. Though it's never okay for a manager or anyone else to deflect requests for support, you also want to appreciate that you have available to you a vast repertoire of influencing approaches that you might be overlooking.

This “blind spot” approach starts to form an out‐of‐your‐power vicious cycle. We set ourselves up to stay stuck by having limited or ineffective approaches, then we blame the other person for not being cooperative and deepen our hurt that we are not supported, further curtailing our effective approaches.

The more power we hold inside of us and use (not leak, give away, or overlook), the more we have what we want for our life and the bigger our impact with less effort.

Turning a Vicious Cycle into a Virtuous One

These three biologically hardwired processes are the factory settings of your human condition, designed to help you cope with threatening situations. They are instinctive and start out being adaptive.

But these tendencies keep you living your life to satisfy basic biological needs when what you want is to live your life on your terms and to make the contribution you are here for. In your power, you choose how to respond in the face of challenges that could otherwise keep you in survival. You take situations where you and others were stuck in patterns, and you make a new way. You create a virtuous cycle.

On the virtuous cycle of being in your power:

- You maximize what you can control. You have a sense of agency. You stop leaking your power.

- You decide who you want to be and don't personalize or get triggered. You are sovereign over yourself. You stop giving away your power. You source confidence from within and you don't need the other person to change, or to validate you, in order to be in your flow.

- Your approaches are strategic and therefore effective. You have efficacy. You no longer overlook the power you already have. Your problem‐solving helps you get the outcome you want and the collaboration is better than you originally imagined.

On the virtuous cycle, life gets better and better. You trust things will work out for you because you know how to make it so. Your energy is unleashed toward your goals. Ownership of your value is strengthened because the environment actually reflects your talents. Confidence begets boldness and willingness to take risks and share your powerful truths. You get buy‐in for your ideas, attract opportunities, sponsors, and partners, and grow your platform. You attract opportunities like new and next‐level roles, speaking opportunities to help you bring your vision to life. The more you are in your power, the more power you have, so you can share it with others, which is a win‐win and grows your impact.

Expect that across a typical day or week you will be kicked out of your power and have the immediate opportunity to get back in. With proactive practice of the approaches in this book, your bouts of being out of your power will be less frequent and less intense—you will build the muscle memory to come back into your power faster and stay longer. Make it the purpose of your life to stay in—and get back into—your power.

***

Now it's time for you to tap the sense of where you are at your starting point. You can do two exercises. First, take the next full minute and think of a time in your life or an ongoing interaction in which you haven't felt or don't feel in your power. Notice where you feel it in your body, the thoughts you have, and the actions you were tempted to take. This is a good set of cues for you to know you've been kicked out.

Now take a full minute to think of a time where you felt in your power or handled an ongoing situation in that way. Notice where you feel it in your body, the thoughts associated with it, and the responses you are tempted to make/have made. You want this to become your new “home” state of being.

Going forward you can notice when you are out of your power and how you know you are still in your power. Being out of your power is a known experience and will start to become old hat—you can be aware of its early warning signs and welcome it saying, “OOPs” (out of power signal) and have it be the cue to use approaches in this book to get back in.

How well are you already doing at being in your power? You can answer the questions in the quick self‐assessment below the chapter summary to get a high‐level temperature check.

For the full assessment about where you are in your power (or not), and to get recommendations that are personal for your situation, go to www.inyourpowerbook.com.

Notes

- 1. Fifteen years later I presented at the White House, so it turned out to not be once in a lifetime, but who knew? And this shows it's possible for a person to grow into her power!

- 2. Obhi, S. S., Swiderski, K. M., and Brubacher, S. P. “Induced Power Changes the Sense of Agency,” Consciousness and Cognition 21, no. 3 (2012): 1547–1550, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2012.06.008.

- 3. Rock, D., Your Brain at Work: Strategies for Overcoming Distraction, Regaining Focus and Working Smarter All Day Long. New York, NY: Harper Collins, 2010.

- 4. Professor Sukhvinder Obhi interviewed by the author, April 7, 2022, via Zoom.

- 5. Bowlby, John, A Secure Base, New York, NY: Basic Books, 1988.

- 6. Kotler, S., and Wheal, J. Stealing Fire: How Silicon Valley, the Navy Seals, and Maverick Scientists Are Revolutionizing the Way We Live and Work. New York, NY: Dey Street Books, 2018.

- 7. “Priming,” Psychology Today, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/priming.

- 8. Professor Sukhvinder Obhi interviewed by the author, April 7, 2022, via Zoom.