Information literate pedagogy: developing a levels framework for the Open University

Abstract:

This chapter will describe how Open University Library Services has responded to the need for consistent and coherent embedding of information literacy (IL) skills in the undergraduate curriculum by developing an Information Literacy Levels Framework. This articulates the skills outcomes for IL at each stage and shows progression from first-year undergraduate study through to graduation. We outline the background to development of the Framework and the rationale behind its format. We reflect on the process of developing and evaluating it, discuss how it is starting to be used in practice, and conclude with an indication of how it is being expanded.

Introduction

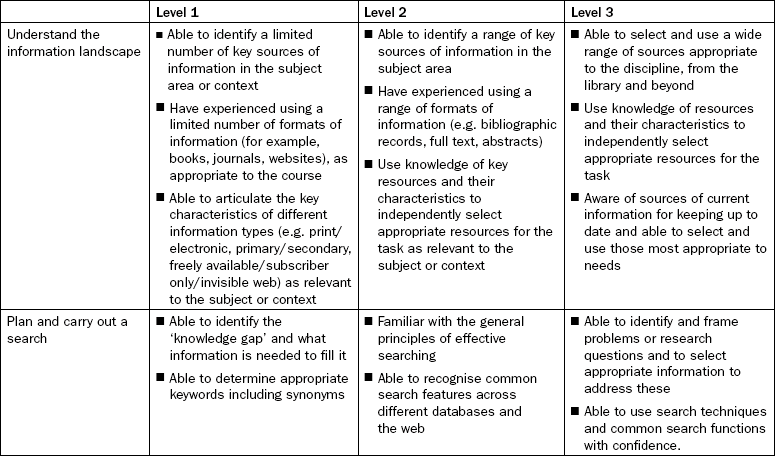

The Open University (OU) Library’s Information Literacy Levels Framework (see Table 2.1) is a document articulating skills outcomes for information literacy (IL) at each stage of the undergraduate curriculum and showing progression from first year undergraduate through to graduation. In what follows we provide an introduction to the Framework, outlining the background to its development, our aspirations in creating it and the rationale behind its format. We reflect on the process of developing and evaluating it, and consider the potential issues which may arise when using it in practice. We offer some thoughts on the support which will be needed for it to be used effectively in teaching and learning and the ways in which we are addressing this. We indicate how it is starting to be used in OU courses. Finally, we look to the future and talk about how the Framework is being extended to go beyond undergraduate study.

Background

When the OU first began to develop distance learning materials in the 1970s, the majority of OU courses were designed to be self-contained. At the time it could not be assumed that all students would be able to access information outside of the course materials. As the World Wide Web began to establish itself in the 1990s, and as the amount of digitised information increased, the OU developed an online library service that could potentially be accessed by all OU students via the Internet. Take-up of the online service was gradual. In the early days of the web not all students had access to the Internet. However, as access increased, the OU began to move to online delivery of courses. This meant that module teams were now in a position to encourage students to use the online library to find information to support their studies outside of the study materials provided.

Alongside these developments, it became clear that the OU Library needed to do more to develop and support the information literacy skills of students and staff, to ensure that both groups could make effective use of the increasing amount of information being made available via the web. In 2002 the OU Library established an Information Literacy Unit (ILU) to raise the profile of IL within the University, and to encourage and support the development of IL skills for OU staff and students. Developments within higher education helped to move the IL agenda forwards, including the Dearing Report (Dearing, 1997), which stated that students needed to become more self-directed and that they should obtain support to develop necessary skills. IL skills were also included in the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) Framework for Higher Education Qualifications (QAA, 2001) and in the subject benchmarking statements (QAA, 2007). The ILU developed an IL strategy for the University, and promoted integration of IL at strategic level, resulting in IL statements being incorporated into OU policy documents.

The OU’s approach to IL has been to adopt a number of models to ensure the broadest range of users have access to opportunities to improve their information literacy skills. These include integration of IL into the curriculum, the provision of generic online IL materials, and standalone modules in IL. However, research suggests that the most effective approach for IL skills development is to embed IL activities within the curriculum. Resources are more likely to be used if integrated, and it is also argued that IL is more meaningful within the context of study: ‘… information literacy skills are not totally generic: they must be developed in the context of a specific subject or discipline because a basic understanding of any discipline is necessary to enable learners to frame pertinent questions with which to evaluate and select appropriate sources.’ (Kirkwood, 2006: 329)

For a number of years, OU librarians have been working with module and programme teams to embed IL skills into new courses in response to the changes outlined above. New Curriculum models are being developed which increasingly require students to research outside their study materials and to develop key skills – including information literacy – for life and work. All course modules now have a website in the Virtual Learning Environment (VLE), which facilitates access to relevant online resources.

The requirement for IL to be fully embedded in the curriculum to promote and enhance student independent learning and progression through programmes has been part of OU high-level strategy since 2006. The current Learning and Teaching Strategy emphasises the importance of a learner-centred approach, which enables students to develop the independent and life-long learning skills they will need to function successfully in a digital world. It has specific objectives to increase information literacy development across the curriculum and to ensure that staff are equipped with the relevant skills.

A number of faculties have developed IL policies which set out in general terms how IL should be integrated into modules and degree programmes within the relevant disciplines. There is, however, still no clear map of the course design process or the point at which IL should be considered. This can result in IL skills being ‘bolted on’, remaining optional, and not being assessed in a valid or reliable fashion. The OU Learning Design Initiative project (Conole et al., 2008) is now starting to address these issues by developing tools and frameworks to support the pedagogical aspects of course production.

There is variation between faculties in the way in which they have adopted IL, in part due to disciplinary differences, but also because of organisational culture. In some cases a shared understanding of the term ‘information literacy’ has yet to be reached between academic and library staff or between academic staff across and within faculties. This is illustrated by the different types of terminology used to describe IL (for example, information handling, information skills, digital literacy) and the way in which academic colleagues perceive the relevant skills. In academics’ own practice, they may have tacit knowledge of IL skills, but the processes, procedures and cognitive skills students must learn in order to become information literate, or indeed to participate effectively in academic life in general (Lea and Street, 1998), may never have been articulated.

Previous work

Our understanding of information literacy at the OU is derived both from external IL sources, and from practical experience of delivering skills material relevant to OU students. The Seven Pillars of Information Literacy statement produced by the Society of College, National and University Libraries (SCONUL, 1999) has been a major influence, as have standards produced by the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL, 2000) in the US, and the Australian and New Zealand Institute for Information Literacy (Bundy, 2004). Exploration and discussion of these and other definitions and standards has helped to formulate our own understanding of IL relevant to our particular context. Work carried out by Peter Godwin (2003) at Southbank University (UK) to describe the level at which IL skills should be developed as students progress through their higher education study provided a useful starting point for the development of an IL levels framework for the OU.

The OU’s Centre for Outcomes Based Education (COBE) is a research and development unit supporting innovative curriculum design, and was initially set up to support module teams in the use of learning outcomes. COBE have produced a range of support materials for academic staff, including the Undergraduate Levels Framework (COBE, 2005), a set of generic level indicators to support curriculum design, which defines IL as ‘finding, critically evaluating and using information’. A summary statement about IL at levels 1–3 of OU study (equivalent to years 1–3 of traditional study) is included within the Framework, providing broad-brush guidance for those involved in module development:

![]() Level 1: Develop your skills in finding, selecting and using information or data in defined contexts.

Level 1: Develop your skills in finding, selecting and using information or data in defined contexts.

![]() Level 2: Find, critically evaluate and use information or data accurately in a range of contexts.

Level 2: Find, critically evaluate and use information or data accurately in a range of contexts.

![]() Level 3: Find, critically evaluate and use information or data accurately in complex contexts.

Level 3: Find, critically evaluate and use information or data accurately in complex contexts.

It is apparent, though, that even where programme and module teams are enthusiastic about incorporating skills, they are often not clear about what to include or how to go about it. Feedback has indicated that the generic level indicators for IL, and for learning outcomes in general, require greater contextualisation and that course programme chairs need clearer direction on what skills-related learning outcomes they should include. An added complexity is the fact that OU students do not all follow set pathways, so prior mastery of skills cannot be assumed at any level.

In 2007 a booklet, ‘Integrating IL into the curriculum’ (COBE), was produced, which started to address these issues by providing guidelines for programme and module teams on how to go about integrating IL, illustrated with case studies. While well-received, this did not go into the detail of what IL skills actually look like at each level of the curriculum or how these skills should develop over the course of a student’s degree programme. The IL Levels Framework aims to fill the gap.

The rationale for the IL Levels Framework

The development of an IL Levels Framework was a natural progression from the brief statement about IL at levels 1–3 provided in the Undergraduate Levels Framework (COBE, 2005). It was felt that it would be beneficial to provide a more detailed breakdown of the skills under the IL banner, and to indicate the level at which students should be developing particular IL skills. It was hoped that the IL Levels Framework could help to support a more consistent approach to the development of IL skills within the university. This would include incorporating progression in IL as students work through the different levels of OU undergraduate study to achieve a degree. The Framework would also help to coordinate the OU Library’s work – taking place simultaneously – to develop a range of generic, reusable learning objects to be integrated within OU modules, ensuring that materials were developed to cover the skills outlined within the Framework.

In developing the IL Levels Framework, we adopted a generic and pragmatic approach, building on the previous IL skills work. However, we have also engaged with research which conceptualises IL using a phenomenographic approach (for example, Markless, 2009; Andretta, 2007; Bruce, 2002, cited in Vezzosi, 2006; Limberg, 2009). This stresses the importance of taking into account context, how students learn, the influence of a web 2.0 environment and the role of reflection at all stages of the process. Markless voices concerns that existing frameworks are too linear in their approach, and over-simplistic about how people engage with information in a digital world. The mechanics of how to search can be overemphasised, with insufficient focus on evaluation, reflection and the creation of new knowledge. It is the development and use of these higher order cognitive skills that ultimately leads to deep and lasting learning with the power to transform the way people think and view the world. Therefore, although we have expressed IL skills in generic terms, we are aware of the considerable evidence in the literature to support the view that IL is a situated practice and cannot be separated from the context in which it is exercised.

The IL skills described within the Framework represent the OU Library’s own view of IL within the University context, influenced by the existing IL frameworks and definitions already referred to. Skills are generic rather than tailored to particular subjects. It is anticipated that different subject disciplines will take a slightly different approach to the development of IL skills, and so the IL Levels Framework is presented as flexible and adaptable within the range of disciplinary contexts at the OU.

The key aims for the IL Framework are: to help develop and integrate IL activities within course materials; to aid skills development and progression through different levels of study; and to provide academic course teams with more detailed guidance on what to include in modules and programmes. It is envisaged that the document will be used by OU librarians working with programme and module teams, as well as by faculty staff working on skills development.

IL skills are grouped within four areas: Understand the information landscape; Plan and carry out a search; Critically evaluate information; Manage and communicate your results. To create a useful working document it was felt that it should be clear and concise, hence the decision to use four areas, as opposed to the seven categories within the SCONUL Seven Pillars, for example. Within each of the areas, IL skills are described at levels 1–3 of OU study (see Table 2.1).

While we have made clear that the Framework is a starting point rather than a prescriptive set of skills and will need to be adapted to context, there is the possibility that it could be interpreted too rigidly or fail to encourage the desired metacognitive attitudes and behaviours. Nevertheless, in the OU context (with packaged course materials the norm until relatively recently), it has been important to start by defining in some detail the skills that undergraduate students should be developing.

Development of the IL Levels Framework

The IL Levels Framework was subject to a critical reading process to ensure validity, with feedback from key stakeholders within the university informing development. The early draft document was reviewed by Learning and Teaching Librarians within the OU Library whose role includes working with academic module teams to embed IL within the curriculum. This led to useful discussions, and key questions that were asked included: at what level should a student develop a particular skill; when should students be proficient in each skill (for example, referencing); and how should we approach overlap with other skill areas such as study skills and digital literacy skills? OU Library staff welcomed the IL Levels Framework, and felt that it would benefit them when working with course teams, particularly if examples of learning materials could be associated to the skills described in the Framework.

A second draft of the IL Levels Framework was circulated to staff in COBE, who responded positively to it, and provided comments which highlighted the link between IL and employability skills. As a result of this feedback it was agreed that a mapping exercise would be carried out between the IL skills and employability skills as a future development.

A small group of academics from different faculties within the OU also gave feedback on the draft levels document. This highlighted some faculty-based skills documents, including undergraduate level skills frameworks for Social Sciences and Health & Social Care, and it was a useful exercise to map the skills within the IL Levels Framework against these faculty documents. This work revealed that the I L levels Framework was largely in agreement with the faculty documents.

One academic welcomed the development of the OU Library’s levels document, and suggested that this could help to develop a shared understanding of IL skills: ‘This is really very useful. I think it helps both you at the library end and us at the Faculty/Programme end to have an integrated approach … ’ (Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Social Sciences).

The positive responses received from academic colleagues are a good indicator that the IL Levels Framework will prove a useful tool when considering IL development within modules and programmes. The evaluations conducted to date have highlighted potential use of the document by faculties considering skills development as a whole, or developing their own IL policies.

Putting it into practice

A natural question raised by academic staff is how the skills set out in the Framework can actually be taught in a distance-learning environment. A VLE website, known as Library Information Literacy (LIL), has been set up to house generic activities which illustrate the skills. The site is intended as a repository for a selective sample of activities, in order to provide best-practice generic models that faculties can either use directly or – more likely – adjust to suit their own context. The four headings of the IL Levels Framework have been used to group the generic activities by skill. Any activities adapted by OU faculties for their specific contexts are listed under the heading for the relevant faculty. Students will be directed to appropriate activities on LIL from the module they are studying.

A key driver is to create some efficiency savings in module production by avoiding the creation of numerous similar but slightly different bespoke activities. It remains to be seen how much reuse of activities occurs in reality, since experience to date does not indicate much enthusiasm on the part of academic colleagues either to use generic learning objects or to incorporate activities not developed for their specific context. Indeed, one might well ask what we mean by a generic activity. It is unlikely that any activity is entirely generic, filtered as it is through the lens of the person who wrote it, with their previous background and experience inevitably rooted in specific contexts. However, faculties are increasingly of the view that activities which are generic at faculty or discipline level can work well when developing skills across programmes. There is also widespread recognition that resources no longer allow for the writing of numerous individual activities at a course module level. In practice, there is a tension between the need to keep costs down by developing generic IL activities, and the view previously discussed that IL skills development works best as a situated practice. We believe that the work described here represents a compromise.

An existing initiative that inspired the creation of the LIL site is the Health and Social Care (HSC) Resource Bank, a repository of relevant online resources, which includes a ‘Finding and using information’ section within the Skills area of the site. The work of other university libraries, for example, the Cardiff University Information Literacy Resource Bank, has also shaped our thinking. Like Cardiff University we have concentrated on short ‘bite-size’ activities, of varying lengths and in different formats, ‘which can be seamlessly integrated into all kinds of teaching materials and fulfil many different purposes’ (Jackson and Mogg, 2007). Example learning objects available on LIL so far include introductions to different types of online resources such as ejournals, ebooks, websites, blogs, wikis, images and multimedia and how to interpret references to these (‘Understand the information landscape’), and activities teaching students how to plan a search, find a journal article from a reference and use Google Scholar to find information in the OU Library collections (‘Plan and carry out a search’).

A template has been developed in order to achieve some consistency of look and feel between the activities on LIL. It includes guidance for OU Library staff on how to set out learning outcomes and how to test them. It also shows how interactivity can be built in (for example, by use of drag and drop activities, video clips, flash animations or quizzes) in order to actively engage learners. Training has been provided to the OU’s Learning and Teaching Librarians to develop understanding of good learning and teaching practice, and how to write for the online environment. It has become clear that a different mind-set is required when creating activities as opposed to writing web pages or demonstrating resources face-to-face. The temptation to tell people everything about a topic must be resisted in favour of writing for the appropriate level and ensuring that the learner is involved in actively doing something rather than just reading text. This is consistent with a constructivist approach and increases the likelihood that deep learning will occur.

These activities have been created in parallel with the development of the IL Framework. A recent exercise, in which activities on the LIL site were mapped to the IL Levels Framework, showed that the majority of activities so far cater for Level 1 skills development, with an emphasis on searching. Future development will need to target those areas where there are gaps and to show how skills develop through Levels 2 and 3. There will also need to be more focus on higher-order skills such as evaluation and reflection.

What support might people need to use it?

Feedback so far indicates that faculties and module teams find the clarification provided by the Framework useful, and are enthusiastic about the idea of having activities to illustrate how the skills can be developed. However, these two things by themselves are not enough to ensure success. Guidance on how to use the Levels Framework in practice will be needed, in order to support OU module teams, and to encourage consistent embedding of skills across programmes and degree awards. The IL Levels Framework indicates where students should be by the end of each level, but not how to actually teach the skills during courses. We will be providing guidance which makes clear for module teams and tutors the link between the Levels Framework and the LIL resource bank of activities.

Help with assessing the skills is also a high priority, to ensure that any assessment that takes place is both valid and reliable. Assessment needs to be appropriate for the type and level of skill. Advice about assessment is being developed by the OU Library to assist module teams with integration of library resources and IL into their modules and programmes. The Cloudworks site, for finding, sharing and discussing learning and teaching ideas, experiences and issues (Open University, 2010), is also being used to share knowledge and interact with the wider community on this and other information literacy-related topics.

Moodle quizzes are starting to be used for formative and summative assessment of skills. This works well for objective testing (right or wrong answers), but is less suitable for higherorder skills such as evaluation or reflection, where outcomes are more open-ended. As Walsh (2009) says, a balance needs to be obtained between ‘a test that is easy to administer with one that will truly assess the varied transferable information skills that information literacy implies’. More reflective forms of assessment, such as portfolios, may be the way forward. Usefulness will be maximised if students can take their portfolio with them into future life and work; the recent adoption of Google Apps by the OU (Sclater, 2010) brings this aspiration closer. Frequent formative assessment would fit well with the model of bite-size activities and an iterative approach to developing the skills. The online environment can facilitate self and peer assessment, reducing the burden on tutors to provide formative feedback, and encouraging students to become self-sufficient. By making explicit what the skills are and at what level they are to be carried out, students can be helped to internalise assessment criteria and develop self-regulation (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick, 2006).

How we will test it: case studies

The next stage in the development of the IL Levels Framework is to test it in some real life situations. Level 2 study is an area requiring more attention across the OU curriculum, in order that students develop the skills they need for Level 3. Feedback from OU Associate Lecturers, who are engaged in front-line teaching of students, indicates that lack of basic IL skills hampers students when they come to more advanced study.

A new second-level Art History module is currently being developed, which will include a significant IL skills component. Although it is uncertain at this stage whether IL skills will be formally assessed, a skills audit is proposed whereby students will do some kind of self-assessment during and at the end of the module. Even if not awarded marks, students will be directed to reflect on their skills as part of assignment preparation, particularly during the later parts of the module. This module is of key importance to bridge the gap between Level 1 and the independent study expected at Level 3 and beyond. If integration of skills is successfully achieved it could act as a model for future Level 2 Arts modules. To evaluate the usefulness of the IL Levels Framework in this situation, an action research approach is being adopted, which will involve a questionnaire to key stakeholders in the Arts faculty and the OU Library. This will be followed up by interviews with selected individuals. The data collected will be analysed to identify any changes needed to the Framework as well as to understand how module teams can best be supported.

Within the Science faculty, work is being done to map skills content of existing courses to the Levels Framework, and a new Level 2 module also provides an opening to integrate IL skills in a systematic way in order to help students make the transition from first to third level study. Likewise, the Social Sciences faculty is developing a new Level 2 module with embedded IL skills which will be compulsory for students wishing to progress to Level 3. It will be instructive to compare the way the IL Levels Framework is used in all these contexts. In the longer term, we will want to evaluate the effectiveness of the Levels Framework with students, in order to determine the impact of the Framework on their OU study success.

Possible issues

There is a considerable body of theory and research which shows that context is important to students (for example, Laurillard, 2002; Biggs, 2003). Faculties will need to adapt the Framework to their particular requirements, and to express outcomes in language which resonates with the academic discourse of their disciplines, as well as with desired employability outcomes. We will need to address the question of how well the IL Levels Framework can be applied to specific disciplines and learning contexts. It will be important to communicate clearly to tutors what skills students are expected to develop, at what level and how these relate to the workplace, and to give students the words to articulate this for themselves. We may also want to acknowledge more explicitly the importance of social and collaborative learning in the development of IL skills.

Thought is being given to how to implement skills outcomes across programmes, as it is not practical or desirable to include all skills in all modules. Brown (2001) suggests that each skill be included at least twice in each degree programme. With the move towards an awards-based approach at the OU, this should become more achievable.

Future developments

The IL Levels Framework is a living document and will most likely change over time. Over the next year, the Framework will be promoted across the OU with a view to getting it adopted into the OU curriculum. The Integrating Information Literacy into the Curriculum booklet is being rewritten to include the IL Levels Framework. There are also plans to put the IL Levels Framework online with links to relevant activities. Further evaluation work will be needed once the Framework has been in use for a reasonable period of time: with OU librarians to find out how the document is being used; with the teams responsible for writing OU courses; and also with OU Associate Lecturers (ALs) who work directly with students. It will be interesting to consider how ALs view the IL Levels Framework, and what impact it might have on the support they provide to students. The IL Levels Framework is part of work being carried out to implement an OU-wide pedagogical approach to course development. In future, learning design tools should flag up to programme and module teams where IL fits into the course as a whole and the IL Framework will provide the detail of what skills should be covered.

Feedback from OU academics has shown that module teams place high importance on developing students’ employability skills and that there is considerable overlap between IL and employability skills. Work is currently underway to map the skills described in the IL Levels Framework to employability skills. Following on from that, consideration will be given to the best way of presenting the results of the mapping exercise to module teams. This is so that they can use this information for course planning purposes to develop IL skills and also to show students how these skills are transferrable and can be highly valued within the workplace.

There is interest from academics in expanding the IL Framework to include OU Openings courses, which are introductory level modules aimed at students who want a taster of OU study. A number of faculties working on Masters level courses are also keen to see the Framework extended to included post-graduate study. Therefore, in addition to mapping the IL Levels Framework to employability skills, the next phase of this work will also develop IL skills outcomes for the stages which precede and follow undergraduate study.

Taking a broader view, information literacy can be seen as one of the tools (University of Melbourne, 2009) and enablers (Todd, 2005, cited in Markless, 2009) of life-long learning, and a holistic view needs to be taken of the way in which students interact with information. A number of institutions have adopted a ‘learning literacies’ approach, which sees IL as part of a wider landscape and as one of ‘the range of practices that underpin effective learning in a digital age’ (LLIDA, 2009). For example, at Edge Hill University, information literacy has been integrated with study skills to align it more closely with academic practice within disciplines. At the OU, a key objective is the integration of IL skills into modules and programmes to promote independent thinking and researching. We also aspire to fuller integration of information literacy skills materials into OU study skills support.

Conclusion

The overall aim of the Framework is to improve student learning and the student experience by promoting IL and embedding it within the curriculum. It is our hope that the Framework will enable those working on the ground creating OU courses to fulfil the aspirations of high-level university strategy and faculty policy, by providing a tool-set to help shape their thinking and course design. In this way, top-down and bottom-up initiatives can be brought together in a coherent way. The importance of academic literacies is increasingly being recognised, especially for students from non-traditional backgrounds who may have little or no experience of academic conventions. The IL Levels Framework has an important contribution to make to this and positions the OU Library as an equal partner in the course development process. The framework also helps to underpin good pedagogy and the ideal of constructive alignment (Biggs, 2003) by ensuring that learning outcomes, learning activities and assessment are all consistent with each other. Finally, in the words of Lord Puttnam, OU Chancellor: ‘I do think anyone with an OU degree should be brilliantly familiar with information gathering on the web. The idea you will graduate from the OU without being a world-class researcher yourself, should be nonsense. We should be challenging students to find their own links, and their own information. I’m not sure we’re doing this enough’ (Cook, 2009: 2). The IL Levels Framework is about helping to equip students with 21st century skills and ensuring that OU graduates are able not only to survive but to thrive in the world in which they live and work.

References

ACRL. Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education, Association of College and Research Libraries, American Library Association. Available from: http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/acrl/standards/informationliteracycompetency.cfm, 2000. [(accessed 14 March 2010)].

Andretta, S. Phenomenography: a conceptual framework for information literacy education. Aslib Proceedings: New Information Perspectives. 2007; 59(2):152–168.

Biggs, J. Teaching for Quality Learning at University: What the Student Does (2nd edn). Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press; 2003.

Brown, G. Assessment: A Guide for Lecturers. LTSN Generic Centre Learning and Teaching Support Network; 2001.

Bundy, A., Australian and New Zealand Information Literacy Framework: Principles, Standards and Practice. 2nd edn. Australian and New Zealand Institute for Information Literacy, Adelaide, 2004. http://www.caul.edu.au/info-literacy/InfoLiteracyFramework.pdf [Available from:, (accessed 14 March 2010)].

COBE. Integrating Information Literacy into the Curriculum. Milton Keynes: Centre for Outcomes Based Education, The Open University; 2007.

COBE. Undergraduate Levels Framework. Milton Keynes: Centre for Outcomes Based Education, The Open University; 2005.

Conole, G., Weller, M., Culver, J., Brasher, A., Cross, S., Clark, P., Williams, P. OU Learning Design Initiative, Open University. Available from: http://ouldi.open.ac.uk/, 2008. [(accessed 29 April 2010)].

Cook, Y. What are we going to look like at 50?: interview with Lord Puttnam. Society Matters. 2009; 12:1–2.

Dearing, R., National Committee of Inquiry into Higher Education (NCIHE). Higher Education in the Learning Society: The Dearing Report. London: NCIHE; 1997.

Godwin, P. Information literacy, but at what level? In: Martin A., Rader H., eds. Information and IT Literacy: Enabling Learning in the 21st Century. London: Facet, 2003.

Jackson, C., Mogg, R. The Information Literacy Resource Bank: re-purposing the wheel. Journal of Information Literacy. 2007; 1(1):49–53.

Kirkwood, A. Going outside the box: skills development, cultural change and the use of on-line resources. Computers & Education. 2006; 47(3):316–331.

Laurillard, D. Rethinking University Teaching: A Conversational Framework for the Effective use of Learning Technologies, 2nd edn. London: RoutledgeFalmer; 2002.

Lea, M.R., Street, B.V. Student writing in higher education: an academic literacies approach. Studies in Higher Education. 1998; 23(2):157.

Limberg, L. Information literacies beyond rhetoric: developing research and practice at the intersection between information seeking and learning: keynote address, i3 conference, Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, 24 June 2009. Available from: http://rgu-sim.rgu.ac.uk/i3conf/presentations/Limberg_i3KeynotelnfoLiteracy.pdf, 2009. [(accessed 30 April 2010)].

LLIDA. Learning Literacies for a Digital Age, Caledonian Academy. available from: http://www.academy.gcal.ac.uk/llida/, 2009. [(accessed 30 April 2010)].

Markless, S., A new conception of information literacy for the digital learning environment in higher education. Nordic Journal of Information Literacy in Higher Education. 2009;1(1):25–40. https://noril.uib.no/index.php/noril/article/view/17 [Available from:, (accessed 30 April 2010)].

Nicol, D.J., Macfarlane-Dick, D. Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education. 2006; 31(2):199–218.

University, Open. Cloudworks, Open University. Available from: http://cloudworks.ac.uk/, 2010. [(accessed 30 April 2010)].

QAA, Subject Benchmark Statements, Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education. 2007. http://www.qaa.ac.uk/academicinfrastructure/benchmark/default.asp [Available from:, (accessed 30 April 2010)].

QAA, The Framework for Higher Education Qualifications in England, Wales and Northern Ireland – January 2001. 2001. Available from: http://www.qaa.ac.uk/academicinfrastructure/FHEQ/EWNI/default.asp#framework [(accessed 30 April 2010).].

Sclater, N., OU adopts Google Apps for education’. Virtual learning blog, posted 22 January 2010. 2010. Available from: http://sclater.com/blog/?p=399 [(accessed 30 April 2010).].

SCONUL. The Seven Pillars of Information Literacy, Society of College, National and University Libraries. Available from: http://www.sconul.ac.uk/groups/information_literacy/seven_pillars.html, 1999. [(accessed 14 March 2010)].

University of Melbourne, Assessment and Teaching of 21st Century Skills (ATC21S). 2009. http://www.atc21s.org/home/ [Available from:, (accessed 30 April 2010).].

Vezzosi, M. Information literacy and action research: an overview and some reflections. New Library World. 2006; 107(7–8):286–301.

Walsh, A. Information literacy assessment: where do we start? Journal of Librarianship and Information Science. 2009; 41(1):19–28.