Chapter 5

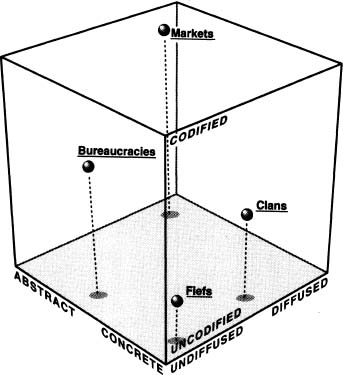

Social and economic transactions provide the impetus for the production and exchange of information. Transactions, however, entail effort and incur costs and are thus subject to attempts at economizing through institutional arrangements. In the l-space, we distinguish between four basic types of transactional structures:

1Markets, in which transactionally relevant information is well codified, abstract, and widely diffused.

2Bureaucracies, in which transactionally relevant information is well codified and abstract, but whose diffusion is under strict central control.

3Clans, in which transactionally relevant information is uncodified, concrete, and only diffused to small groups.

4Fiefs, in which transactionally relevant information is uncodified, concrete, and undiffused.

These transactional structures are both the products and shapers of information flows. Where such flows are stable and recurrent, such structures will metamorphose into institutions.

Institutions impart a certain facticity to their knowledge base and are treated as stores of potential intelligence. Since such stores help to economize on data processing, transactions tend to gravitate towards those regions of the l-space well endowed with prior institutional investments. Institutions, however, not only enjoy a limited reach in the l-space, but also are prone to obsolescence on account of the effects of new information flows.

As pointed out in the preceding chapter, economics, although acknowledging the importance of information in economic exchange, has tended to concern itself primarily with information asymmetries and hence with the diffusion dimension of the I-space. By largely ignoring the influence of codification and abstraction on the distribution of information, it has been led to an essentially static form of institutional analysis that greatly underestimates the creative scope for learning in an economic system.

Investing in the I-space

Whether movement in the I-space occurs cyclically, as we have hypothesized that it does when new knowledge is created, or whether it is random, it entails efforts and incurs costs in time, effort, resources and so on. What specific activities are associated with these costs? Essentially, those of problem-solving and of learning by doing in the case of vertical movement along C and back, those of repetition and testing along ĀA, and those of transmitting and receiving information in the case of horizontal movement along D. For the larger part of our waking moments, many of these costs might be considered trivial and may not even be reckoned such. A mother reading a bedtime story to her child (transmitting information) or a schoolboy mastering a computer game on his father's PC (absorption) may not think of themselves as particularly burdened; indeed, they may actively enjoy what they are doing. From a more analytical perspective, however, this is just another way of saying that what they get out of their respective activities justifies the effort that they put into them so that each is willing to invest time while their satisfaction lasts.

The willingness of the mother to invest time in bedtime reading may not be simply a question of immediate enjoyment, much as this may also be present. She may have more complex investment criteria involving the need to give her offspring a good start in life, the desire to develop a strong parental bond, and so on. Even if she is tired and not particularly inclined to read, she may still pull herself together and make the necessary effort if she takes a longer-term view of the benefits that accrue from this activity. The schoolboy's interest in his computer game, however, is likely to be more volatile. His father may rejoice at the idea that he is acquiring sophisticated technical skills, but at the point that the game bores him, he will drop it without a further thought and move on to his Spiderman comic or his Lego set.

The cost-benefit calculations performed by the mother and the schoolboy are likely to be unconscious or at best intuitive and informal. The mother does not sit down with pencil and paper to compute how many increments of career progression for her child an extra five minutes of bedtime reading will yield. Yet certain types of movements in the I-space require such levels of effort that they will only be undertaken following a fairly searching analysis. The problem-solving activities that make up a major research and development project, for example, may call for several hundred man-years of highly skilled and painstaking effort; or again the advertising campaign required to educate a market to the use of a radically new technical product – a diffusion cost – may run into tens of millions of dollars, and so on.

An important distinction should be drawn between the example of the mother and that of the schoolboy. Since the mother is communicating with her child, there is a sense in which the movement of information in the data field is visible; the child smiles, laughs, gasps, and generally provides feedback. By watching for this feedback we know whether or not data has effectively been transmitted. In the case of the schoolboy, by contrast, everything is hidden or impacted; whatever skill he has absorbed sitting alone in front of his father's PC remains his unique possession until, through some form of social interaction, he is led to show what he knows. Indeed, it may be in anticipation of such a future interaction that he is striving for mastery. He may, for example, be practising for a casual game with friends, or even for a tournament. In the latter case, the expected benefits of his efforts will run beyond the enjoyment of the moment and he may become willing to invest a correspondingly higher level of effort in practising his game. Indeed, he might now try to calculate informally what such a level should be in terms of other activities forgone that he would have preferred to pursue – i.e., hanging out with the gang, going to a movie, etc. But now, as in the case of the mother and her child, movement in the I-space is prompted by the prospects of a future return, a form of exchange with the schoolboy's physical or social environment whose consummation is spread out in space and in time.

Transactions

The use of information may be central to a physical or a social exchange or may be quite peripheral to it; for our purposes it matters not. In either case information ends up as support for a transaction between an agent and its environment, steering it towards desired outcomes and triggering adjustments on the way. In this chapter, we shall take transactions as the driving force behind the creation and use of information, giving a purpose and a logic to its flow and evolution in the data field. Transactions, past, present, and prospective, energize the field and endow it with a characteristic structure, accessible through the I-space.

Clearly, we are here using the term transaction in a broader sense than is common in economics where it has been taken as the ultimate unit of microeconomic analysis.1 Simplifying somewhat, we might say that if money drives economic transactions, information drives transactions in general. Yet what is money if not a physical store of information? Like money, codified information can be a store of value, a measure of value, as well as a means of exchange; at certain times, one of these functions will predominate, at others another one will. And just as making money and exchanging it productively for goods and services require an intelligent expenditure of effort over time, and, usually, well ahead of a transaction, so do the production and exchange of information. In short, effective transacting requires prior investment.

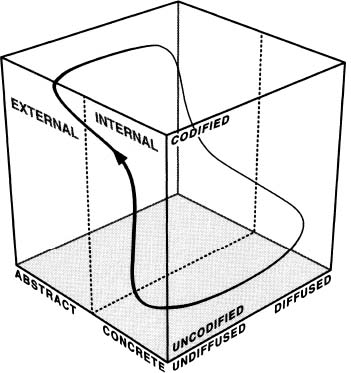

At times, the creation of information may appear to be only loosely related to the transactions in which it might be used. The schoolboy playing around with a game on his microcomputer, for example, may only decide that he is of ‘tournament class’ after he has already achieved a measure of proficiency and this may have been quite casually acquired. He may not initially have thought of consciously investing time and effort to achieve a particular skill level. Yet looking back, he discovers that intentionally or not he has effectively invested himself and that his ‘learning by doing’ has moved him down the I-space from C, where he possessed no more than basic knowledge of the rules of the game, towards , where he had implicitly internalized strategies and a feel for promising patterns of play.2 He can now transact from a position in the space which was possibly inaccessible to him six months before.

To summarize, the production of information and its use in transactions both incur costs and are thus subject to economizing. In the 1970s, there occurred a revival of interest among economists in the economics of transaction, and Oliver Williamson in particular, building on the earlier work of Ronald Coase and John Commons, has explored the different institutional arrangements which govern transactional choices.3 In this chapter, we shall also concern ourselves with the institutional order built up from transactions, but our focus will be less narrowly economic than the one adopted by Williamson. Like him, we shall argue that institutional structures aim partly at achieving transactional efficiencies and that where such efficiencies are effectively achieved they act somewhat like a magnetic field – a mathematician would call them ‘attractors’ – drawing the uncommitted transaction into a given institutional orbit. Yet in contrast to Williamson's, our concept of transactions is underpinned by an explicit rather than an implicit theory of information production and exchange which yields a different way of classifying them as well as a distinctive approach to their governance. We find ourselves in consequence in the realm of political economy rather than of economics tout court.

In the next chapter, we shall show how the institutions that crystallize out of transactional structures mediate a cultural order; a powerful link between institutional economics and cultural analysis is thus established. Attempts to build such a link have been made before, notably by William Ouchi;4 yet Ouchi, I feel, had underestimated the role that must be played by information in such an analysis. By treating, as we intend to do, transactional structures and institutions as emergent phenomena in a data field, we are placing the information environment in which a transaction occurs at the heart of our analysis.

Structures and processes

In what way might an individual's or a group's access to information influence the terms on which they enter into different forms of social exchange? Cast in the language of the I-space, the question becomes ‘What roles do the codification, abstraction, and diffusion of information play in the way that an individual or a group construct and enact their social world?’ We share Mary Douglas's ambition to go beyond the assertion put out by social phenomenology that the individual's life-world (Umwelt) is socially constructed.5 Like her, we would like to know what kinds of worlds are likely to be constructed when social relations take on this or that form. Yet we could equally well run the lines of causal influence in reverse and ask what kinds of social relationships are brought forth by a given way of constructing the world. A materialist position sees the life-world as all superstructure, an emanation from the social and economic relationships which it expresses with modest, if any, causal powers of its own. An idealist position, conversely, subordinates the creation of social and economic structures to the imperatives of a particular cosmology or world view. It argues, so to speak, either from design or from an all-embracing universal concept.6 The flow of information in the data field can effectively accommodate both approaches, since it is both channelled by structures – social, physical, cognitive, etc. -and in turn serves to build these up. Structures are zones of stability in a dynamic process that reach out into the field to modify its configuration. Structure and process here mutually determine each other. The resulting patterns can be exceedingly complex and no description of these will be attempted here. Our aim, more modestly, is to identify the type of structure that is likely to crystallize out of information flows in certain regions of the data field – what Max Weber, in another discourse, would have labelled ideal types – and briefly to investigate both its intrinsic social attributes and how these might be modified by the action of the SLC over time. Our approach remains consistent with the connectionist metaphor discussed in Chapter 2. Transactions activate complex patterns of information exchange within a network of agents in potential interaction with each other. The patterns themselves are the product of excitatory or inhibitory links between individual transactions that compete or collaborate with each other. The analogy with the behaviour of neural nets should need no further elaboration.

A transactional typology

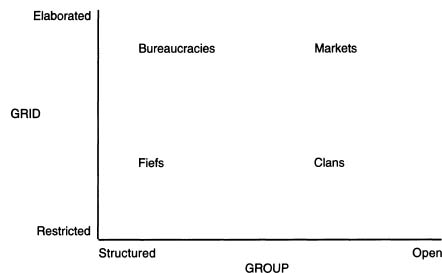

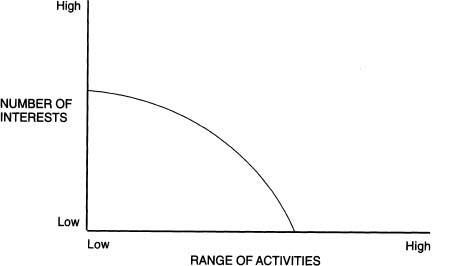

It is the SLC itself which brings forth transactional structures in the I-space; articulations of distinct phases in its trajectory. In this chapter we identify four such structures. There may be more in practice but we believe these will be hybrids and thus not amenable to analysis as ideal types. The location of our four structures is shown in Figure 5.1. We have labelled them markets, bureaucracies, clans, and fiefs, the first three in deference to existing transactional typologies, and the last one on account of its provocative connotations.7

The fact that existing transactional typologies such as those of Williamson and Ouchi might be made to fit into the I-space amounts to a quick and dirty test for the plausibility of our claim that transactional structures can be viewed as an emergent property of information flows. What then needs to be established in the sections that follow is how far the social patterns of behaviour associated with each structure could reasonably be predicted from the characteristics of the information environment in which they occur. More challengingly, one would expect to discern some systematic relationship between the dynamic evolution of the data field brought about by information flows themselves and shifts of emphasis in the building up and maintenance of institutions away from one type of structure and towards one better adapted to new constraints imposed by the changing nature of the data. At a macroscopic scale, that at which the aggregation of transactional populations in the SLC yields discernible institutional patterns, one could then reasonably expect any shift that occurs between structures to tell us something about the nature of social evolution. This will be the subject of Chapter 6.

Figure 5.1 A transactional typology

We next examine our transactional structures individually.

In the case of pure markets we are dealing with transactions the effectiveness of which depends on the provision of two items of well-codified, abstract information being available to all members in a given population: quantities and prices. Yet if such information is so available it will be because it is abstract and well codified. Of course, much non-codified and concrete information is also often widely distributed in a population and is therefore collaterally available in market transactions, but since it tends to diffuse only slowly and mostly in face-to-face situations, it is subject to lags, leakages, and distortions. Given that with respect to this second type of information, one can hardly argue that everyone is in possession of the same transactional information as required by the theory of efficient markets,8 it has tended until recently to be either underemphasized or ignored.

Codified, abstract information can be acquired and transmitted by impersonal means. Although impersonality is usually associated with large distances and in our day with modern communications technology, it is also quite viable in many face-to-face relationships. The key point is that in an impersonal social exchange, one is not essentially concerned with the identity of the other party even if this happens to be knowable. It would be unusual, for example, to enquire into the family background, personality, or value system of a street newspaper vendor before deciding to purchase an evening paper. If both the price and the type of contents of the paper are known beforehand, the transaction will be brief and to the point – indeed, in the typical case, it may even be wordless. Both parties will be concerned to minimize the time taken up by the transaction and get on with other business – if, say, it takes place during the evening rush hour when the vendor expects to make his/her best sales to large volumes of people hurrying home, personalizing the relationship with any one buyer will be bad business. Anyone, such as an out-of-town tourist, who starts asking for transactional information on the newspaper's price or its contents, may receive a pretty curt reply to his/her questions. The purchaser is in fact expected to know the paper's price and its contents.

On the other hand, transpose this hapless tourist to a Saudi Arabian souk where codified information on the goods displayed is neither much available nor much diffused, and the transaction acquires quite a different character. Here, personalizing the relationship will become the central requirement of a bargaining process which proceeds, like Walras's auctioneer, by tâtonnement.9 Yet Walras's auctioneer strives for impersonal outcomes since these help to speed up the process. The auctioneer is helped in this by the fact that he/she finds himself in a multilateral bargaining situation in which buyers and sometimes sellers are anxious not to reveal their respective identities. In the souk, however, bargaining will be bilateral in nature. Since everyone does not possess the same information as to price, quality, or the level of demand, it pays both parties to find out more about each other. The seller, for instance, might wish to discriminate pricewise between buyers who are ‘wised-up’ and those who are not. The buyer may wish to know more about the product's quality and the seller's honesty in describing it. Both sides will therefore be attentive to nuance and context, looking for clues, and ‘sizing up’ the other.10

Although buying a newspaper from a street vendor and buying an article in a Saudi Arabian souk are both characterized as market exchanges, the key difference between the two kinds of transaction is that the ready availability of relevant codified information to both parties in the first case places the buyer and the seller on an equal footing. In contrast to the case in the Saudi souk, the cost of haggling is eliminated for both parties. The newspaper seller knows that she will not get a purchaser to pay more and the latter will not expect to pay less than the going rate for an evening paper.

Efficient versus real markets

This first kind of transaction is therefore somewhat closer to what economists refer to as efficient markets. Only somewhat, however, since the price of an evening paper does not respond to every fluctuation in supply and demand conditions but is set in anticipation of future market trends. Thus a knowledge of price by the parties avoids haggling and reduces transaction costs, but it only affects the price itself with a lag.

Depending as they do on the speedy and extensive diffusion of abstract codified information, efficient markets have become the paradigm case of economic exchange. In the real world, however, they are also extremely rare and, for the most part, represent something one aspires to rather than expects. Why? There are many possible reasons for this. Here we shall give only two. Firstly, as markets increase in efficiency, the larger the number of players that are made to compete on an equal footing. This requires the freedom to enter or exit markets in response to price movements. In reality, however, and for practical reasons, most markets are limited in size so that over time some players may acquire a disproportionate weight relative to others. They are then in a position to influence price-volume relationships and become price makers rather than price takers. In fact, it has only been with the advent of information technologies that allow continuous trading across space and time that certain types of markets have been able to approximate the economist's definition of efficiency. In earlier times markets were intermittent affairs that found it hard to bring together would-be buyers and sellers in one place. The Champagne fairs of the thirteenth century, for example, took place on certain fixed dates only – usually five or six times a year – and involved such high transaction costs for the parties that for the most part only luxury goods could justifiably be traded there.11

Secondly, and more problematically, a market only achieves efficiency where the prices at which trading occurs embody all the transactionally relevant information available to buyers and sellers. Thus not only does price behaviour reflect current trading conditions, but everything that is currently known about future trading conditions as well. This ‘rational expectations’ view of markets in effect amounts to a requirement that all such transactional information be fully codified, abstracted, and diffused.12

The workings of the SLC itself should alert us to the near impossibility of ever fully satisfying this requirement. A price that is the outcome of bilateral bargaining between economic agents (a priori, therefore, this excludes our newspaper vendor) is a local affair that has the character of a hypothesis to be tested both against knowledge of ‘local circumstances of time and place’13and against non-local, abstract knowledge of prices practised elsewhere. Much of the local knowledge that goes to make up the price in fact stays local, but the price struck only effectively captures it as transactionally relevant information if the hypothesis is a good one, i.e., if exchange actually takes place at that price14 and if that price effectively has implications for exchange practised non-locally.

Defenders of the rational expectation view will argue that it is not essential to start with good hypotheses concerning prices providing that subsequent hypotheses are corrigible and can be improved by learning. In other words, local prices are tested against the market price and all other available information and adjusted accordingly.15 Learning so defined contributes to the movement of prices towards equilibrium, that unique price at which the market is cleared.

Markets and learning processes

Some light upon this issue can be shed by Ross Ashby's ‘law of requisite variety’.16 The law states that learning, to be effective, must operate at a rate that matches that of changes occurring in the organism's environment. The law does not guarantee that such learning, even if effective, will necessarily also be epistemologically correct: it may, after all, be built on a faulty hypothesis.17 The rational expectations hypothesis ignores this feature of the law of requisite variety and takes market learning to be epistemologically unproblematic. Systematic errors are sooner or later weeded out and random errors do not impede the learning process.18 It is thus, by assumption, that market learning contributes to an equilibrating process and movement towards a single equilibrium price. And if, as one approaches equilibrium, the rate of change in the market environment decreases, the rate of learning by economic agents is, so to speak, allowed to ‘catch up’.

Yet our SLC points to the possibility that a move away from equilibrium is itself the fruit of a learning process – i.e., knowledge absorption – which impacts what might otherwise be available knowledge in the heads of a few well-situated individuals capable of using it opportunistically and in novel ways. It thus becomes once more concrete and local – i.e., undiffused. To present this disequilibrating process merely as an interlude between two equilibrium points, as rational expectation theorists are prone to do on the argument that disequilibrium will sooner or later be followed by equilibrium, is to miss the essence of the phenomenon.

Clearly, any breach of the two conditions mentioned above – namely, that market entry and exit should be unimpeded and that market price should capture all available information – will tend to push transactions out of the market region and towards other parts of the I-space. The smaller the number of players, for example, the more likely it is that their identity as well as their relative size will begin to matter and that their behaviour will in fact embody local information known to them but not to others. They can then behave ‘strategically’19 with respect to other agents in the market who are less well informed. Strategic behaviour, of course, shows up in price movements and is thus sooner or later communicated. But it usually does so too late to matter, particularly where early learning has been successfully impacted and has allowed strategic actors to move away from equilibrium in opportunistic ways. In the absence of equilibrium, therefore, a market sometimes becomes the location in the I-space where ‘suckers’ are to be found, and these are unlikely to gain much consolation from the knowledge that others will one day learn from their mistakes.

One way of avoiding the ‘small numbers’ condition, as we have seen, is to make entry and exit into the market unrestricted. Any profit resulting from monopolistic positions would then immediately attract new entrants. The small-numbers condition itself, of course, if persistent, moves one either towards bureaucracies or towards clans in the I-space as the transactionally relevant population shrinks. Where market-relevant information has not been fully abstracted, codified, and captured by the price, transactions are more likely to migrate towards clans than towards bureaucracies. Some of the more local uncodified information relevant to transactions will then only be transmitted face to face and will therefore no longer be available to all would-be participants. It will only be passed on to those close at hand: to colleagues, friends, and relatives who may consequently enjoy an information advantage with respect to ‘outsiders’.

It is worth noting that the two impediments to market efficiency just described – i.e., barriers to entry and an inadequate codification and abstraction of transactionally relevant information – tend to mutually reinforce each other. Transacting among small numbers, for example, will tend to stabilize relationships and increase the opportunities for personalizing them and thus for transmitting uncodified information face to face. Yet transacting with uncodified and concrete information is an uncertain, time-consuming business that will automatically tend to limit the number of participants that can be involved.

Moving in the I-space towards clans and moving towards bureaucracies, however, involve quite different responses to the workings of SLC. In the first case, one follows the cycle out of the market region in a way that might almost be called ‘natural’ since the move away from equilibrium and towards small numbers in effect reflects a form of market learning (absorption) and impacting. In the second case one moves against the cycle by explicitly setting up barriers to the diffusion of codified abstract knowledge (see next section).

The markets which today are considered to come closest to achieving the efficiency ideal are financial markets in industrialized economies. Not only do they now benefit from a telecommunications technology that ensures a rapid diffusion of codified information – a price movement on Wall Street, for example, will be registered in a matter of seconds in both London and Hong Kong – but with the growing integration of national financial markets into a single global one, they have increased severalfold the number of players who can freely participate in their operations.

Yet, as the ‘insider trading’ scandals of recent years amply demonstrate, even in so-called efficient markets, information is never fully codified, abstracted, or diffused. Market prices continue to conceal as much as they reveal and small numbers lurk opportunistically within the large numbers required for transactional efficiency.

Markets and social values

Economists will continue to debate whether the asymmetric distribution of market-relevant information constitutes an insuperable barrier to the attainment of transactional efficiency as technically defined. Yet efficiency can also be impaired by how the presence of information asymmetries is perceived by participants themselves. Why else would insider trading scandals ‘rock’ Wall Street? Why should a few winks and nods between eminent and established figures of the financial community land them with four- or five-year jail sentences? There is little mystery here: by their behaviour such people may not have posed any great threat to market efficiency as technically defined by rational expectation theorists; but in being perceived to benefit unfairly from an information advantage they were challenging the value system of the market as an institution. It is this value system that keeps a market working as close to its ideal as is feasible under given circumstances and, in the absence of its lubricating effects, both confidence in the fairness of the institution and a willingness to use it for transactional purposes will be undermined. If too many people leave the market in search of more equitable alternatives, large numbers will once more give way to small numbers and the market's efficiency will be further compromised.20

Can components of this value system be identified? Perhaps the two core values that underpin market transactions are a belief in individual rationality and a belief in competition as a regulating mechanism.

A belief in individual rationality received its most powerful formulation in the philosophies of the Enlightenment as systemized by d'Holbach21 and, in economics, its most popular articulation in the writings of Adam Smith. Simply stated, it holds that individuals are quite capable of deciding for themselves what constitute their real interests and of then going about satisfying these in sensible ways, always providing that they are adequately informed as to what their real options are. Individual rationality, to be effective, thus presupposes access to transactionally relevant information.

Individual rationality per se, however, does not necessarily yield socially desirable outcomes, and it would never by itself have commanded the attention it has done had not another important insight also been available. For if individuals can be shown to be rational in the pusuit of their own goals what is to guarantee that such goals, when aggregated across a large number of individuals, are in any way compatible with each other or that if they are not, social harmony can ever be preserved?

Adam Smith was certainly not the only one to see how the market might resolve this dilemma in the eighteenth century, but he gave the solution its most broadly intelligible formulation. He did not argue, as many have taken him to, that the selfish pursuit of individual interests was ethical,22 but merely that it was reasonable. Smith held that if self-interested individuals could be put into regulated competition with each other in pursuit of their respective goals, then, from a social point of view, there was no need to pass judgement on the ethical worth of these goals; they were in effect a matter for the individual and his conscience. Socially efficient outcomes could be secured in spite of the selfish pursuit of individuals, providing the latter could be made to compete fully and fairly with each other. Under such circumstances individual rationality would be productive of social rationality and the information generated by countless local transactions would be used by the market to regulate itself.23

Social welfare will only be maximized in this self-regulating scheme, however, when competitors are numerous and small, when no transaction is of such a size as to produce distorting effects, when no barriers exist to prevent people from entering or leaving the market, and finally when competitors cannot collude to form powerful subgroups. It is, of course, this last condition that ‘insider trading’ violates, thereby demonstrating how difficult it is to satisfy these requirements in practice even in the most sophisticated and best-functioning markets.

Linked to these core values are other values that are not always made explicit but are none the less implied by markets as an equitable institutional order. For example, freedom to choose goes hand in hand with a belief in personal responsibility for one's own fate, which in turn translates into a social value stressing equality of opportunity rather than equality of outcome.24 Put more harshly, rational men are equally free to make choices -some will be good, some will be poor; in all cases, though, they must bear the consequences. The doctrine of personal responsibility promotes both tolerance and impersonality. Tolerance, because if each individual is free to pursue personal objectives according to his own lights, then he must not be unduly constrained in doing so through the moral judgement of others – in this sense, markets are pluralistic as well as individualistic. Impersonality, because any concern with the identity and welfare of the other party to a transaction beyond that minimum required by civility and the preservation of the social order can act as a brake on one's own maximization objectives and hence to the detriment of a properly competitive relationship. Thus collusion between free economic agents, that is, those not bound by blood relationships or those of employment, translates into the pursuit of a group welfare function which threatens the atomism of the market, and by implication its efficiency as an allocator of social resources.25

Perhaps the most fundamental social value underpinning the institution of markets remains the belief that an individual must be left free to pursue his life chances as he sees them. Possibly originating in the medieval doctrine of the sanctity of the individual soul, the acknowledged primacy of individual over collective goals, coupled with a growing understanding of how the latter could be served by the former through the mechanism of self-regulation, gradually came to erode the perceived legitimacy of the mercantile state in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Markets have existed in some form or other in most cultures and in most historical periods but nearly always in a subordinate role to other institutions. Only in western liberal doctrine were they later to be elevated into a dominant component of the social order, albeit one maintained by the regulatory power of the state – the latter exercised through a form of bilateral governance in which markets retain the leading role.

Markets as a social order

The automatic self-regulatory nature of efficient market processes, however, largely does away with the need for state direction in those regions where markets rule. Inspired by the politically as well as the economically liberating implications of ideas of self-regulation, ‘He governs best who governs least’ then became the slogan of laissez-faire capitalism in the nineteenth century, some of whose protagonists held that much of social life could be reduced to market processes supervised by a ‘nightwatchman state’. What had initially evolved as a governance structure for certain classes of transactions then for true believers became elevated to the status of an ideology which could reign over the social order as a whole – indeed, by appropriating Darwin's theory of natural selection for its own purposes after the theory's publication in 1859, market ideology could expand hegemonistically to claim dominion over organic life itself.26

Although these hegemonistic impulses of market ideology have since been somewhat reined in, market processes still remain the dominant paradigm for economic transactions in those countries where free market institutions were allowed to flourish.27 They increasingly came to be perceived as an integral part of the natural order with market equilibrium expressing an underlying tendency of the social system as a whole towards stability when this is unimpeded by external ‘disturbances’.28 The whole arrangement is magnificently Newtonian since once the metaphysics of equilibrium has been suitably established – this could only be done mathematically, not empirically – any move away from the equilibrium point became by definition an ‘external’ disturbance and hence of no threat to the metaphysical core of the doctrine. As Williamson puts it in Markets and Hierarchies, ‘in the beginning there were markets’,29 and the economist's concept of ‘market failure’ is a normative presumption in favour of market transactions which implicitly casts alternative forms of governance as second best.

As we have seen above, where ‘market failure’ occurs on information grounds, it will move transactions towards those regions of the I-space occupied by bureaucracies or clans, in the first case pushing against the flow of the SLC, in the second, moving along with it and allowing it to run its course. We consider bureaucracies next.

The informational characteristics of bureaucracies

Like market transactions, bureaucratic ones depend on the use of well-codified and mostly abstract information – financial budgets, monthly reports, economic assessments, statistical surveys, etc. But now this information is no longer available to all agents as it might be in a market. It is the authorized possession of a limited number of individuals who thereby stand to gain a legitimate transactional advantage from it.

The theory of the SLC is built upon the premise that information has a natural tendency to diffuse when it is codified and abstract so that in effect it has little inherent stability in that region of the I-space where bureaucracies are to be found. If information is to remain there, as it must if bureaucratic institutions are to emerge at all, barriers to its diffusion must be erected. And it is the very presence of such barriers that gives bureaucratic transactions their particular flavour.

Barriers are not necessarily designed to block the diffusion of information as such, but simply to make it controllable by designated individuals. In contrast to the market case, in bureaucracies diffusion ceases to be a random process with receivers colliding haphazardly into messages that are somehow ‘out there’ for the taking. Messages are now distributed discreetly on a point-to-point basis with further redistribution also taking place selectively. If the appropriate metaphor for the diffusion of information in a market is that of an Alka-Seltzer tablet dissolving in water, the one that best conveys bureaucratic information processing is that of the central nervous system, a hierarchically structured communication network. Of course, if we consider that knowledge is power, then the differential possession of transactional information confers considerable advantage to individuals who operate the barriers to its diffusion. The information resources under their control put them in a position of strength in many forms of social exchange, and the institutionalization of transactions in this region of the I-space is therefore designed to ensure that the circumstances in which such individuals come to possess valued information, and the use to which it is then put, are both perceived to be socially legitimate. A confidential report, for example, transmitted by a government's intelligence services to a head of state is not expected to be widely diffused; its restricted circulation will usually be granted a high degree of legitimacy by the country's citizens given the threat to their security posed by any leaks. A publicly quoted industrial corporation, on the other hand, which sought to prevent the publication of its financial accounts in order to avoid answering embarrassing questions at a shareholders’ meeting might quickly provoke an outcry. The first type of transaction therefore is a plausible candidate for bureaucratic governance whereas the second should properly be assigned to market governance.

But how are individuals effectively selected for the privilege of operating barriers to information diffusion? What criteria are used? In the real world, these are numerous and they are applied with varying degrees of rigour. In the case of the pure bureaucratic transaction, however – the ideal type – we need only retain two: competence and accountability.

Competence and accountability

The competence criterion ensures that only those who know how to use the information they receive do in fact get it, and that those who do not are kept out of the distribution channel. The decision-maker has to be capable of evaluating and interpreting transactional information received prior to deciding how it should be used and to whom it should be further distributed. For this he/she needs a knowledge of context to guide his/her analysis. What the decision-maker then decides to retransmit up or down the communication hierarchy is always the product of an act of selection; i.e., an abstraction and a codification. Competence, therefore, has to extend beyond the identification of appropriate nodes in the communication network with which to interact, and cover as well an ability to formulate appropriate messages in an intelligible code in order to overcome Shannon's three communication problems.30 The consummate bureaucrat is, above all, a consummate communicator.

The accountability criterion is required to ensure that the privileged possession of information does not lead to abuse. In a bureaucracy, individuals are no longer free to pursue their own personal objectives as they are in a market. Objectives are now hierarchically imposed from above. Individuals are granted power and authority in a bureaucracy to the extent that they accept as their own objectives that are handed down. They are not required to subscribe to these personally, merely to act as if they did. Yet it is sometimes easy for individuals holding such power privileges to exploit them for ends that have little or no institutional legitimacy. They must therefore be constrained in their behaviour either by the presence of external control systems designed to render their behaviour visible, or through the gradual development of a personal value system that can act as an internalized control system. Where transactions are well codified and based on abstract principles and can therefore be recorded and made visible, the first kind of control system might be preferred. Where the information used in transactions is concrete and cannot be so codified, however, only those who have been socialized to the required value system and can demonstrate a credible commitment to it will be entrusted with its possession. The latter case, however, ceases to describe a purely bureaucratic transaction; it properly belongs to the fief region of the I-space and will be further discussed in section 5.6. Yet in both instances the differential possession of information creates a hierarchical transactional structure; in bureaucracies this becomes a formal and specialized communication network based on impersonal authority. In contrast to fiefs, therefore, power in bureaucracies is constrained by structure.

Roles and routines

A formal communication hierarchy possesses distinctive properties. For a start, the authority relations it describes are built largely upon expertise. Eligibility for a particular position is determined by meritocratic criteria that stress both competence and accountability. Then, since such a hierarchy deals with codified information, its transactional style tends to remain largely impersonal. Roles – i.e., the codification and standardization of behaviour patterns – rather than the vagaries of personalities and of individual identities are what matter. Roles express behavioural clusters of specialized knowledge and expertise that serve to mutually orient both the senders and receivers of codified abstract information. Roles also allow transactions themselves to be standardized and subsequently routinized so that larger volumes of information can then be processed by the hierarchy. But since roles reflect the logic of standardized transactional requirements rather than individual idiosyncrasies, they also demand impersonality. Just as in a pure market transaction at a given price, one customer is as good as another, so in a pure bureaucratic transaction, providing that each party possesses the required competence and sense of accountability, one role incumbent is as good as another.31

Bureaucracies typically, but not always,32 involve smaller numbers than markets do, although they tend to deal in more varied and more complex information than markets can properly handle. A market is designed to process large volumes of abstract data coded as prices and quantities. Bureaucracies also deal with abstract codified data, which can therefore be written down on paper, but it is often of a kind that cannot so easily be standardized. Disparate kinds of written data – on personnel records, legislation, budgets, etc., – have to be reconciled in ways that often call for a knowledge of context and the exercise of personal judgement. Of course, bureaucratic routines that integrate and structure transactional information into more manageable wholes are constantly being sought; yet since such routines cannot deal with every unforeseen contingency – remember that codification involves selection from a limited set of alternative possibilities -a certain number of transactions will inevitably fall outside their scope. These will be ‘referred upwards’ and thus travel up the hierarchy until they find a procedure – which may or may not be routinized – for dealing with them.

This upward drift of transactions for which no suitable code exists at a lower hierarchical level suggests that, whatever the nature of the organization, not all transactions in a hierarchy can be purely bureaucratic, and that as a consequence fuzzy, unanalysable, non-routine decisions must inevitably gravitate towards the top. As we shall see in section 5.6, such transactions belong in fiefs. The point that we wish to make here, however, is that since, in contrast to what prices are meant to do in markets, codes cannot completely capture all the information relevant to bureaucratic transactions, these occupy a position somewhat lower down the codification dimension than markets do in the I-space and remain somewhat less abstract (see Figure 5.1).

Bureaucratic values

How does the value system that underpins bureaucratic transactions compare with that of markets? Certain values the two institutional orders will share; in other respects they are totally different.

Take, for example, rationality. Both markets and bureaucracies aim at the rational integration of means and ends and both make use of codified and abstract information for achieving this. But here the resemblance ends. Defenders of markets believe that each individual exercises rationality in the pursuit of his own personal goals and that, providing that enough of the relevant information is available to all, this atomistic collection of goal-seeking individuals achieves optimum social outcomes through a process of self-regulation. Individual rationality under efficient market governance thus generates social rationality with little or no leakage. Defenders of bureaucracy, by contrast, challenge this automatic transposition of rationality from the individual to the collective level. Not only might self-regulating processes not function properly, but even if they did they might still fail to bring about socially desirable outcomes. These must then be secured by hierarchical means. Certain carefully chosen individuals will therefore be legally empowered to represent the collective interest and to pursue it through a process of hierarchical coordination.33 Relations between different levels of the hierarchy will then be based on the exercise of authority, legitimated by expertise rather than by market power. As Max Weber has defined them, bureaucratic relations are based on a belief in rational-legal order.34

Those in authority, then, are deemed to know more than their subordinates and this gives them the power to coordinate the allocation of resources; the use of that power will be considered legitimate by those who submit to it as long as it is applied to social rather than personal ends. By assuming at the outset an asymmetric distribution of information among social and economic agents, bureaucracy may be thought to require less heroic assumptions than markets. In practice this may be so, but a bureaucratic ideology, by positing the existence of the all-seeing professional administrator working selflessly in the service of society, strains our credulity in other ways.35 The synoptic abstract rationality of markets has not been done away with, but merely monopolized by those who, now calling themselves ‘central planners’, sit atop the administrative hierarchy.

Bureaucracies also share with markets a concern for stability and a Newtonian world view that sees change as the externally generated disturbance of a system wanting to move towards equilibrium. Yet in bureaucracies, the system does not move towards equilibrium unaided: the invisible hand of the market is replaced by the visible hand of an all-knowing administration drawing on information that is for the most part codified, abstract, but not diffused.

The stability of a hierarchical order is in fact incompatible with the widespread and uncontrolled diffusion of the transactional information on which it rests; the non-sharing of information consequently becomes a deeply entrenched bureaucratic value among those who cherish such stability. If market institutions struggle against insider trading and the exploitation of information asymmetries, bureaucratic ones by contrast strive to prevent ‘leaks’ of valuable transactional information: self-regulation requires information sharing; hierarchical coordination requires information hoarding. Interestingly enough, in both cases, institutional transgressions take the form of an uncodified and concrete transaction – a social exchange whose transient face-to-face nature remains hidden to all but the few involved in it and which subsequently leaves no trace.

A third important bureaucratic value briefly touched on above and irrelevant to the functioning of efficient markets is that of professionalism, which harnesses the privileged possession of specialized knowledge and competence to an ethic of service. Professionalism in fact operates in two modes:

1It serves to legitimize the non-diffusion of diffusible information by arguing that such information ‘getting into the wrong hands’ would not serve the public interest. The implication here is that the ‘right hands’ do serve the public interest and are prepared to subordinate private goals to public ones. A professional bureaucrat or ‘public servant’, for example, is someone who not only has the technical competence to select the means once the ends have been decided, but, within certain politically definable limits, gives himself the moral right to select the ends themselves. The bureaucrat's commitment to an ethic of service qualifies him/her to specify social goals, whether this be done selectively (i.e., in situations where collective choice finds no coherent expression either in markets or through the ballot box36 – in other words, where markets fail) or more comprehensively, as in command economies, where individual choice is granted from the outset a low level of legitimacy. The social counterpart to the technical and moral authority of the professional bureaucrat, of course, is obedience from subordinates and compliance or at least acquiescence from clients.

2It serves to bolster the exercise of highly personal idiosyncratic skills in ill-defined situations where a high degree of interpersonal trust between the parties is required if a transaction is to take place at all. A doctor-patient relationship or a lawyer with his client typify this kind of social exchange. As in the first mode described above, there is information asymmetry between the transacting parties, but here such information is intrinsically hard to codify and thus does not transmit easily between a professional and her client. The latter, therefore, not only has to take on trust that the former has the requisite ability to perform the service that is being solicited for, but also that she is willing to use it exclusively in the client's own interest.37

As we shall see in section 5.5, the second mode in which professionalism operates properly belongs to the clan region of the I-space and is not in fact representative of the bureaucratic transaction as such. It is more personalized and involves smaller numbers than the latter, since in bureaucracies professional competence and accountability can be effectively achieved, and on a larger scale, by more impersonal means.38

Bureaucratic competition

Bureaucratic transactions, no less than market ones, involve competition between participants, and in both cases individual success involves moving from a position on the right in the I-space, where one is a net recipient of knowledge, towards a position on the left along the diffusion curve, where one becomes a net contributor.

But surely, it might be objected, on the right we do not find bureaucracies but markets. Was this not after all the burden of section 5.3? What would a bureaucrat be doing on the right anyway unless he had lost control of his stock of information? The answer is that transactional structures compete with each other throughout the I-space but are better positioned to survive in some parts of the space than in others on account of the fit that obtains between their information requirements and the characteristics of their local information environment. Thus, for example, a market represents a limiting case of hierarchical decentralization, the point at which information parity between all actors in an organization effectively allows self-regulating processes to take over from hierarchical coordination. Yet until one reaches the top right-hand corner of the I-space, some measure of hierarchical coordination remains possible. Where transactional possibilities overlap in this way, we may either view the situation as one in which bureaucracies extend themselves to the right along the diffusion scale reaching into markets to impose a measure of hierarchical structure – such would be the case, for example, where natural monopolies are regulated by the state – or, conversely, we may see market processes moving leftward along the diffusion scale and penetrating bureaucracies in the form of internal organizational competition – between divisions, functional units, individuals, etc. How does such competition work in practice?

Both Adam Smith and later Joseph Schumpeter realized that no player actually enjoys the rigours of pure competition and that players will do what they can to escape it by attempting to secure for themselves some monopolistic advantage – today the term used is ‘competitive advantage’: it sounds less offensive while retaining essentially the same meaning.39 Smith saw the phenomenon somewhat statically as a source of economic inefficiency to be deplored, whereas Schumpeter thought of it in more dynamic terms as a stimulus to innovation.40 He understood that the quest for competitive advantage and the flight from pure competition themselves constituted competitive processes that brought but temporary relief. Either way, a monopolistic control of markets resting on an information advantage amounts to a leftward move in the I-space and away from the purely competitive case.

The quest for competitive advantage characterizes a bureaucracy no less than a market. A move up an organizational hierarchy where there are fewer players confers an information advantage that is monopolistic in nature and that also translates into a leftward movement in the I-space: information has to be shared with a smaller percentage of the transactionally relevant population. Yet a leftward move in a bureaucracy remains in principle meritocratic and rests on competence and accountability rather than on raw market power. Nevertheless, both bureaucratic and market moves towards the left share a common aspiration to overcome the barriers to entry that will inevitably be found there in order to escape the turbulence of competition on the right. When these barriers have been crossed, transactions can then navigate in calmer waters; thoughtful people can now see where they are going and appropriate courses of action can be chartered. Competition has not of course been completely eliminated on the left of the diffusion scale, but it becomes a more leisurely, more gentlemanly affair involving but a few players.41

The bureaucratic order

If individual freedom in a self-regulating cosmos remains the dominant value underpinning market transactions, the necessity of subordinating individuals to collective interests and a belief in the power of orderly and rational planning characterize the bureaucratic outlooks. The ‘blindness’ of markets, with no competent hand to guide them, is abhorred and considered to be a social aberration. If, as Williamson claims, in the beginning there were only markets, then it must surely follow that in a progressive society the move away from a Hobbesian ‘war of all against all’ and towards the security and serenity of hierarchy must count as a desirable outcome. The regression towards markets, the drift towards the right in the I-space, must then amount to a form of ‘bureaucratic failure’.

Many liberals would argue, however, that societal evolution actually requires bureaucratic failure. When citizens all enjoy high levels of education, then information asymmetries can no longer be justified on welfare grounds. The absolutist state of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the paradigm case of a bureaucratic order,42 was only possible while the coding skills conferred by education remained in the hands of an administrative elite. With industrialization and the spread of mass education this asymmetry ceased to be tenable. It was maintained in place on a large scale by the Marxist-Leninist state – a twentieth-century attempt at state absolutism – in those countries where mass education had not yet emerged: the USSR, China. Where mass education is available, however, it gradually erodes a pure bureaucratic order from within – witness Eastern Europe in 1989, and in 1991 the Soviet Union itself.43

In the People's Republic of China, on the other hand, where mass education is not yet widely available above – or even at – primary school level,44 the bureaucracy, whilst failing to deliver, has not in fact ‘failed’ in favour of markets. An examination of the SLC reveals that markets are in fact not the only resting place for failed bureaucracies. Like markets themselves moving towards bureaucracies, the latter can also move against the cycle: towards fiefs. As we shall see in section 5.6 and illustrate in Chapter 7, this is a move towards feudalism. Before considering this alternative form of bureaucratic failure, however, let us first examine the second way that markets themselves can fail, when, allowing the SLC to follow its natural course, they move into clans.

The information characteristics of clans

Markets fail when information asymmetries between transacting parties create a small-numbers condition and the self-regulating nature of the exchange process can no longer be assumed. A hierarchical governance structure might then emerge either to complement or to replace market processes. Is hierarchy the only option?

Information asymmetries, as we have seen, can arise in a number of ways. Those codifying new knowledge on the left of the I-space, for example, may choose to be selective in what they diffuse – such is often the case with patent disclosures: enough is revealed to secure the patent but not enough to allow imitation by would-be competitors. Alternatively, creators of new knowledge may actually be unable to fully codify or abstract from certain areas of their experience which must consequently remain concrete and personal to them. In both these cases the clockwise progress of the SLC itself is slowed down, thus maintaining existing information asymmetries.

Moving against the cycle in an anti-clockwise direction in the upper region of the I-space, on the other hand, is another way of either maintaining or creating information asymmetries. It can mean developing proprietary coding skills for oneself, and then using them to make one's own discoveries or using them to gain privileged access to newly codified, abstract, but as yet undiffused knowledge. Bureaucratic competition pursues information asymmetries through either option; it consists of a regulated manoeuvring for position as far to the left as possible along the diffusion scale.

Yet information asymmetries can also result from following the SLC rather than either slowing it down or moving against it, from an absorption of codified, abstract knowledge that is subsequently impacted in idiosyncratic and possibly creative – but now uncodified – ways. Put another way, markets also fail when the learning-by-doing opportunities that they offer are skewed in favour of a small number of individuals who thereby gain a ‘first mover’ advantage from knowledge that is hard to articulate or to disclose.45

The small-numbers condition

The communication constraints imposed by uncodified and concrete information tend by themselves to generate a small-numbers condition since the number of agents that one can maintain a worthwhile face-to-face relationship with remains of necessity limited. We shall label small face-to-face groups that operate on the basis of shared but largely uncodified and concrete, i.e., local, information, clans. They represent a case of limited information diffusion in which a group of ‘insiders’ collectively enjoys an information advantage with respect to ‘outsiders’.

Some of the authors who have studied the dynamics of transactions in clans tend to see many of them essentially as the outcome of instabilities in political and economic markets. Both Michels in Political Parties46 and Olson in The Logic of Collective Action47 call into question the self-regulating character of market transactions. And Axelrod in The Evolution of Cooperation48 further demonstrates that the payoff to small-group collaboration in recurrent conditions will always be higher than to competition involving large numbers. The implication seems to be that institutional attempts to keep small groups of regularly transacting parties in a purely competitive arm's-length exchange relationship will often be subverted by the interest they have in banding together and in personalizing their dealings with each other.

Oliver Williamson and Alfred Chandler, by contrast, both see small-numbers clan transactions as being themselves unstable and subject to erosion by the logic of markets. Chandler, for example, in his study of the repeated attempts by many US industries to cartelize their operations at the turn of the century, found them to be short-lived and plagued by defections. Relations between cartel members were characterized by a lack of trust and a lack of any durably effective policing devices that could compensate for the lack of trust.49

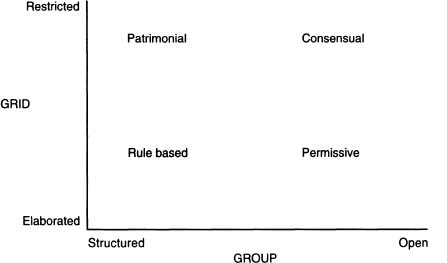

Clearly, interpersonal trust must be counted an important ingredient in bringing about stability in clan transactions. Yet this quality of personal relationships, so important to information sharing behaviour when transactional data is uncodified and local, is subsumed by Williamson under the catch-all label of ‘atmosphere’ and is thus not perceived by him as extending the range of transactional options beyond those that he originally identified; i.e., those of markets (the large-numbers condition) and hierarchies (what we have termed bureaucracies) which usually regroup larger numbers than clans (although not always) yet smaller numbers than efficient markets, these being in theory open to everyone.50 William Ouchi, one of Williamson's collaborators, has analysed the concept of the clan as a governance structure in its own right51 and others have at various times referred to communes52 or federations53 as equally viable transactional possibilities. Yet none of these authors have conceptualized clans as anything other than a transactional form located in an intermediate position along the diffusion scale between markets and hierarchies.

Clans, however, are assignable to the lower region of the I-space. They deal essentially in fuzzy information which is diffusible enough to be shared by clan members in a given time period but not by the population as a whole. Should we characterize the data used by clans as tending towards the abstract or the concrete? Given the location of clan transactions on the SLC, we are tempted to answer ‘the concrete’ and in most cases this is likely to be right. Clans will treat as critical the local, particularistic data that affects the day-to-day working of clan life. Yet one can conceive of groupings whose essential concerns and ultimate effectiveness might well require a shared base of abstract knowledge. This might be truer, though, of a purely scientific community than, say, of a professional association whose primary mission might be to defend the interests of its members in the wider society – even if it does this while proclaiming its adherence to abstract values.

Exceptions such as the scientific community apart, clans exemplify the distinction drawn by the cultural anthropologist Edward Hall54 between ‘high context’ and ‘low context’ cultures. The distinction is almost directly derivable from differences in their respective information environments: high context cultures deal with rich, concrete, uncodified data in face-to-face situations that are complex, multidimensional and subtle, whereas low context cultures orient their transactions towards the selective use of codified abstract data in clear, simple, impersonal settings.

As with Williamson's typology, Hall's also turns out to be only half the story. If in the first case markets and hierarchies as institutionalized information processing structures can only be located along the diffusion dimension of the I-space on account of Williamson's almost exclusive theoretical focus on information asymmetries, Hall's high context and low context cultures can only be placed in the E-space. Hall is in fact aware that context affects information-sharing behaviour but his observations do not lead to any theoretical analysis of this phenomenon that might cause him to refine or extend his typology. The phenomenon of information diffusion is left out of the picture.

The issue of trust

Clan transactions are inherently uncertain. Markets can handle risk where the possible range of outcomes and their likelihood of occurrence can be specified sufficiently to shape expectations. They are less well equipped to handle uncertainty.55 How does transactional uncertainty arise? When neither the range of external contingencies faced by transacting parties, nor their possible responses, can be identified and assigned probabilities in advance; when, for example, it is impossible to be sure that someone faced with overwhelming opportunities or threats will remain steadfast in honouring earlier commitments which turn out subsequently to be vague or leaky. Market contracting then becomes an unreliable device for securing such commitment since it acknowledges as legitimate any self-seeking behaviour not specifically constrained by enforceable contract clauses or external legislation. Caveat emptor is as much of a comment on the informational deficiencies of markets where complete contacts cannot be written as it is on human nature as we know it.

Clan transactions assume information parity among clan members and for this reason they partly escape the ‘moral hazard’ issue that arises when one party possesses transactionally relevant information that the other does not. I say ‘partly’ because one information asymmetry remains; namely, a transacting individual's knowledge of her own intentions. She may choose to disclose these or she may not. In markets characterized by spot contracting, such disclosure is hard to elicit; the parties meet, exchange, and go their own ways. They owe each other nothing beyond civility. In more continuous interactions, however, intentions may gradually be discerned. The extensive socialization efforts associated with effective clan governance are specifically designed to keep such intentions mutually aligned.56

The elimination of moral hazard through a shared pattern of socialization is best achieved with small numbers. In any dealings between clan and outsiders, the moral hazard issue is likely to retain its full force. Within the clan structure itself, participants develop implicit forms of communication which simultaneously affirm and reinforce their ‘apartness’ from non-members; i.e., their exclusive access to a collectively apprehended reality that is either opaque or possibly invisible to outsiders. Apartness bolsters a group's identity and creates ‘barriers to entry’ which can be as varied as the initiation rites to which novices must submit on entering a religious community and the screening that applicants are put through before being admitted as members of an exclusive golf club.

Moral hazard is extensively discussed by Williamson who comes very close to the concept of information absorption, the move towards , in his analysis of information impactedness – a condition in which information sharing is perceived to be too costly to undertake on account of a transaction's lack of codifiability. Yet impacted information in Williamson's analysis simply moves one along D further to the left and towards hierarchies tout court; by leaving to one side issues of codification and abstraction, it can yield no further transactional options.

Uncertain and complex transactions pose the problem of trust in an acute way and the greater the uncertainty, the greater the amount of trust between the parties needed to overcome it. As we shall see in section 5.6, the need for interpersonal trust grows greater as one moves towards Ās in the I-space. Yet trust effectively turns out to be a required ingredient of all transactions in the lower region of the space – i.e., in Ā – where transactional contingencies can never be fully specified and catered for.

Trust relationships cannot be decreed. They either evolve or they do not. An understanding of the circumstances in which trust flourishes can be helpful in building it up, but it will remain a hit or miss affair dependent on a wide range of factors such as personality, cognition, prior familiarity with issues and agents, and so on. Prior familiarity seems to be a particularly important requirement in fostering attitudes of trust towards expected outcomes. Is there in fact any difference between the paratrooper who trusts that his parachute will open when he tumbles out of the aircraft thus saving him from a certain death, and the wounded infantryman who trusts his ‘buddies’ not to abandon him to the enemy as they pull back under attack? The former ‘knows’ his equipment and the latter ‘knows’ his buddies.

Trust is primarily a matter of prior familiarity and grounded expectations: the attribution by those who possess it of a higher probability to ostensibly uncertain outcomes or events than those lacking such familiarity would be willing to grant. Yet since familiarity requires time to build up, trust cannot be given freely beyond the boundaries within which familiarity has had time to evolve. These boundaries may gradually be pushed outwards but since one cannot be familiar with everything, whatever stock of trust is available must of necessity either get spread more thinly across people and events or it must be more selectively invested. One is then moved by degrees to trust classes of events rather than events themselves, and categories of people rather than specific individuals. What is gained in extension by codifying and abstracting in this way, however, is lost in intensity so that trust becomes a form of taken for granted knowledge subject to revision.

Of course, the process cuts both ways: a loss of trust in an individual can rapidly contaminate the social categories he is placed in. One of the major purposes of professional codes of conduct, for example, is to maintain a high degree of public trust in a group of people who exercise uncodified skills on a fiduciary basis. Professions stand to lose a great deal should that trust disappear, which is why they are often allowed to police themselves. In attempting to do so, however, they face a paradox in that the built-in disposition to trust colleagues in clan organization creates a bias in favour of the insider at the expense of the outsider – in this case the client or the public at large57 – so that self-policing tends to become self-serving.

Clans and shared values

How does one minimize the risks involved in the granting of interpersonal trust? One looks for clues: background, reputation, affiliations, etc. But what constitutes a promising clue in a given situation will itself be the fruit of prior familiarity, of ‘learning by doing’, of a downward and horizontal move towards Ā in which information is absorbed and impacted in intangible ways. In clans such learning is a collective process. For this reason, people who share a common background, a shared system of values, will be quicker to trust each other than those who do not. The process of transmitting transactionally relevant information will be more efficient since much of it can be done implicitly – the old school tie, a certain accent or choice of words, a particular way of dressing, etc. A would-be ‘con-man’ has to, master a host of implicit codes before he is in a position to abuse people's trust. And it is precisely when the con-man fails to to ‘absorb’ the necessary codes – that is, when he has gained access to them as an outsider rather than as an insider, and thus leaves them in their unadapted, codified form – that he is unmasked. He treats them as stereotypes whose nuances escape him. He rings false for reasons that those who do possess the codes may not themselves be able to articulate. Is this not precisely the problem that ‘new wealth’ faces in passing itself off for ‘old wealth’? Does not the hurried effort at mastering the appropriate codes show through? Not always as clumsiness, but sometimes as a kind of technical virtuosity that smacks of overachievement?

The scope for the effective exercise of interpersonal trust is limited either by the number of people that can be known personally – i.e., that can be the focus of prior uncodified transactional investments – or by the number of implicit or explicit categories available to an individual for deriving reliable behavioural predictions. The weakness of stereotyping in addressing such limitations is that it so easily achieves false data processing economies. It amounts to a hurried construction of explicit categories based on traits or features that more often than not offer poor predictive value. Stereotyping leads to false generalizations about individuals that one has had no time to know better; it becomes in effect a substitute for trust, one that is sometimes imposed by cognitive overload. It is primarily the need for trust that confines clans, in contrast to markets, to comparatively small numbers and in particular to that number with whom values can be shared and expectations made to converge.

Note that convergent expectations and values do not imply that transacting parties actually have to like each other or that they must necessarily share the same goals. They must, however, be able to anticipate each other and get on to ‘the same wavelength’ in a process of mutual adjustment. They must also be united by some superordinate values or goals, however remote, that are capable of maintaining the relationship in spite of divergencies in individual interest – some of these, indeed, might actually form the focus of the transaction. For unlike market transactions, which in their pure form are quite transient and disembodied, clan transactions are deeply embedded in, and shape, long-term social relationships.58

Consider, by way of illustration, the price fixing behaviour of a cartel. Much of the information used to reach a decision is not traded outside the group and much of it is exchanged informally in a face-to-face situation – the proverbial smoke-filled room. Since in most circumstances in a free market economy, a cartel is considered illegal, agreements must remain uncodified and must not be leaked to any party outside the group. A copious economic literature on the ‘signalling’ practices of cartels, the corporate winks and nods by which their members adjust their behaviours and align their expectations, bears witness to the uncodified and highly local nature of this communication process.59

And yet cartels, as Chandler and others have shown, tend to be unstable structures.60 They tend to break down when eroded by the opportunistic behaviour of their members. After all, these remain competitors at least as much as they might be collaborators. As in the Prisoner's Dilemma, the payoff to defection tends to be higher in many cases than the rewards of conformity to group discipline.61 In the face of such persistent divergencies of interests should we consider cartels to be viable clan structures?

When it comes to pure cartels, probably not. They only exist to serve a narrowly overlapping set of membership interests and no superordinate goal structure exists to make the payoff to adherence more attractive than that to defection where this can be practised either undetected or without penalty. Yet many structures economically organized as cartels successfully manage to survive by endowing themselves with a broader purpose, one which not only gives their members a collective identity that they can live with but one which also bestows upon the group a high degree of social legitimacy – in short, they find ways of increasing the degree of overlap in their members ‘ individual interests.