What is an ‘edge’ over the markets – and do you have it?

A key premise of this book is that we can’t legally beat the markets consistently, or indeed know of an investor that can. It concedes having an edge over the markets. But what is meant by this?

Consider these two investment portfolios:

- A: The S&P 500 Index Investment.

- B: A portfolio consisting of a number of stocks from the S&P 500; any number of stocks from that index that you think will outperform the index. It could be one stock or 499 stocks, or anything in between, or even the 500 stocks weighted differently from the index (which is based on market-value weighting).

If you can ensure the consistent outperformance of portfolio B over portfolio A, even after the higher fees and expenses associated with creating portfolio B, you have gained an edge by investing in the S&P 500. If you can’t, you don’t have an edge.

On first glance it may seem easy to have an edge over the S&P 500. All you have to do is pick a subset of 500 stocks that will do better than the rest, and surely there are a number of predictable duds in there. In fact, all you would have to do is to find one dud, omit that from the rest and you would already be ahead. How hard can that be? Similarly, all you would have to do is to pick one winner and you would also be ahead.

While the examples in this chapter are from the stock market, investors can have an edge in virtually any kind of investment. In fact there are so many different ways to have an edge that it may seem like an admission of ignorance to some to renounce all of them. Gut instinct may tell investors that not only do they want to have an edge, but the idea of not even trying to gain it is a cheap surrender. They want to take on the markets and outperform to make money, but perhaps also as a vindication that they ‘get it’, are street smart or somehow have a superior intellect.

The competition

When considering your edge who is it exactly that you have an edge over? The other market participants obviously, but instead of a faceless mass think about who they actually are, what knowledge they have and what analysis they undertake.

Imagine Susan, the portfolio manager of a technology-focused fund working for a highly rated mutual fund/unit trust (let’s call it Ability) who like us is looking at Microsoft.

Susan and Ability have easy access to all the research that is written about Microsoft including the 80-page, in-depth reports from research analysts from all the major banks, including Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs, that have followed Microsoft and all its competitors since Bill Gates started the business. The analysts know all Microsoft’s business lines, down to the programmers who write the code to the marketing groups that come up with the great ads. They may have worked at Microsoft or its competitors, and perhaps went to Harvard or Stanford with senior members of the management team. On top of that, the analysts speak frequently with their banks’ trading groups who are among the market leaders in trading Microsoft shares and can see market moves faster and more accurately than almost any trader.

All research analysts will talk to Susan regularly and at great length because of the commissions Ability’s trading generates. Microsoft is a big position for Ability and Susan reads all the reports thoroughly – it’s important to know what the market thinks. Susan enjoys the technical product development aspects of Microsoft and she feels that she talks the same language as techies, partly because she knew some of them from when she studied computer science at MIT. But Susan’s somewhat ‘nerdy’ demeanour is balanced out by her ‘gut feel’ colleagues, who see bigger picture trends in the technology sector and specifically how Microsoft is perceived in the market and its ability to respond to a changing business environment.

Susan and her colleagues frequently go to IT conferences and have meetings with senior people from Microsoft and peer companies, and are on a first-name basis with most of them. Microsoft also arranged for Ability personnel to visit its senior management at offices around the world, both in sales and development, and Susan also talks to some of Microsoft’s leading clients.

Like the research analysts from the banks, Ability has an army of expert PhDs who study sales trends and spot new potential challenges (they were among the first to spot Facebook and Google). Further, Ability has economists who study the US and global financial system in detail as the world economy affects Microsoft’s performance. Ability also has mathematicians with trading pattern recognition technology to help with the analysis.

Susan loves reading books about technology and every finance/investing book she can get her hands on, including all the Buffett and value investor books.

Susan and her team know everything there is to know about the stocks she follows (including a few things she probably shouldn’t know, but she keeps that close to her chest), some of which are much smaller and less well researched than Microsoft. She is one of the best-rated fund managers in a couple of the comparison sites, but doesn’t pay too much attention to that. After doing her job for over 20 years she knows how quickly things can change and instead focuses on remaining at the top of her game.

Do you think you have an edge over Susan and the thousands of people like her? If you do, you might be brilliant, arrogant, the next Warren Buffett or George Soros, lucky or all of the above. If you don’t, you don’t have an edge. Most people don’t. Most people are better off admitting to themselves that once a company is listed on an exchange and has a market price, then we are better off assuming that this is a price that reflects the stock’s true value, incorporating a future positive return for the stock, but also a risk that things don’t go do plan. So it’s not that all publicly listed companies are good – far from it – but rather that their stock prices incorporate an expectation of a fair future return to the shareholders given the risks.

When I ran my hedge fund I would always think about the fictitious Susan and Ability. I would think of someone super clever, well connected, product savvy yet street smart who had been around the block and knew the inside stories of success and failure. And then I would convince myself that we should not be involved in trades unless we clearly thought we had an edge over them. It is hard to convince yourself that this is possible, and unfortunately even harder sometimes for it to be actually true.

It is hard to pick the right moment

Warren Buffett is quoted as saying that ‘just because markets are efficient most of the time does not mean that they are efficient all of the time’. To quote Buffett about investing is like quoting Tiger Woods about golf. He is a world-famous investor with a long history of being right, so we are all bound to feel a little deferential.

Buffett’s words might be right of course. Markets might be perfectly efficient some or even most of the time and horribly inefficient at other times. But how should we mere mortals know which is when? Can you predict when these moments of inefficiency occur or recognise them when you see them? Clearly we can’t all see the inefficiencies at the same time or the market impact of many investors trying to do the same thing would rectify any inefficiency in an instant. But can you, as an individual investor, spot a time of inefficiency?

I think that it’s incredibly hard to have an edge in the market even occasionally. Be honest with yourself. If you have a long history of picking moments when you spotted a great opportunity, moved in to take advantage of it and then exited with a profit, then you may indeed occasionally have an edge. You should use this edge to get rich.

The costs add up

On average individual investors trying to beat the markets would not systematically pick underperforming stocks – on average they would pick stocks that perform like the overall market. They would have a sub-optimal portfolio that would not be as well diversified, but in my view the main underperformance comes from the costs incurred.

The most obvious cost when you trade a stock is the commission to trade. This has been lowered dramatically with online trading platforms but it is far from the only cost. A few others to consider are:

- bid/offer spread

- price impact

- transaction tax

- turnover

- information/research cost

- capital gains tax

- transfer charge

- custody charge

- advisory charge and

- your time.

Depending on your circumstances and portfolio size you may find that it costs more than 1% each time you trade the portfolio (the low, fixed, online charge per trade is only a small commission percentage if you trade large amounts), excluding the cost of your time. This is certainly less than it used to be decades ago, but for someone who is frequently trading their portfolio it will be a major obstacle to performance. In addition, capital gains tax amounts can add up for frequent traders and the ‘hidden fees’ like custody or direct or indirect costs associated with research and information-gathering come on top. The more this adds up to, the greater the edge someone will need just to keep up with the market.

I recently saw a particularly cringeworthy advertisement where a broker compared trading on its platform to being a fighter pilot, complete with Tom Cruise-style Ray-Ban sunglasses and an adoring blonde. I remember thinking, ‘I would love to sell something to whoever falls for that.’ The platform makes more money the more frequently you trade, and the broker obviously thinks that you will trade more if you believe it’ll make you be like Tom Cruise.

How you cost your time spent managing your portfolio is individual to you (we each value our time differently) and while some consider it a fun hobby or game akin to betting, others consider it a chore they would rather avoid. Someone may spend 10 hours ‘work time’ a week on their portfolio, which at an ‘opportunity cost’ of time of $50 an hour for 40 weeks is $20,000 a year on top of all the other costs discussed. This clearly makes no sense for a $100,000 portfolio and is too costly even for a $1 million portfolio. On top of everything else this investor would benefit from the reduced time involved in running a simple rational portfolio. Also consider that it is only the outperformance you get paid for. Since owning an index tracker takes no time, the cost of time – $20,000 above – actively managing your portfolio is only for the amount you beat the index by. If the index is up 10% and you are up 11% then it is only the 1% excess return that you spent all that time to make. So even in the very unlikely case that you can consistently beat the index you either have to be able to beat it by a lot, or manage a large amount of capital for the time spent to be worth it.

Even if you disagree with me, at least consider this:

Some readers may dismiss this book as a load of rubbish. They may consider themselves to be sophisticated investors who can outperform the market. I hope this group at least has its opinions on edge challenged, and perhaps gets better at defining exactly what its edge is as a result of reading this book. But if you are going to actively manage your own portfolio I would encourage you to consider a few things:

- Be clear about why you have an edge to beat the market, and be sure you are not guilty of selective memory. Unlike predicting the winner of Saturday’s football game, predicting that Google was going to double when it later did makes us appear wise and informed. Perhaps we are subconsciously more likely to remember that than when we proclaimed Enron a doubler. Because we add and take money out of our accounts continuously we are unlikely to keep close track of our exact performance and can continue the delusion indefinitely.

- Do not trade frequently. If you turn over your portfolio more than once a year you should have a really good reason to do so. The all-in costs of trading are high and greatly reduce long-term returns.

- Pick 12–15 stocks you feel great about that are not all in the same sector (preferably also not in the same geographical area) and plan to stick to those for a very long time. Warren Buffett says his favourite holding period is ‘forever’, suggesting that successful investors do not frequently trade in and out of investments.

- Do not start panicking if things go against you.

- You may decide you have an edge in one sector, geographical area or asset class. That’s fine. Do exploit this edge, but invest like a rational investor in the rest of your portfolio.

- Continuously reconsider your edge. There is no shame and probably good money in acknowledging that you belong to the vast majority of people that don’t have an edge. Investors who initially do well in the markets will often think it was skill rather than luck based on that first experience. Many reconsider later …

Should we give our money to Susan and Ability?

If you conclude that Susan is as plugged in and informed as anyone could be, why not just give her our money and let her make us rich?

Many investors do invest their money in the many tech-type products and Ability and its peers continuously develop mutual funds for everything you can imagine. There are funds for industrials, defensive stocks (and defence sector stocks for that matter), gold stocks, oil stocks, telecoms, financials and technology. Many investors have become ‘fund pickers’ instead of ‘stock pickers’. Even today, years after the benefits of index tracking have become clear to many investors there is perhaps $80 invested with managers that try to outperform the index (so-called ‘active’ managers) for every $20 invested in index trackers.

When investors pick from the smorgasbord of tempting-looking funds how do they know which ones are going to outperform in future?

Is it because investors have a feeling that IT stocks (or whatever sub-sector of the market a fund specialises in) will outperform the wider markets?

If so, you are effectively claiming an edge by suggesting that you can pick subsets of the market that will outperform the wider markets? Consistently picking outperforming sectors would be an amazing skill.

Is it because of Susan’s impressive CV (investors think that someone with her impressive background will find a way to outperform the market)?

If so, you are essentially saying that you know someone who has an edge (Susan), which is really another form of edge. This is the kind of edge many hedge fund investors claim. Funds will say, for example, ‘through our painstaking research process we select the few outstanding managers who consistently outperform’. Maybe so, but that is also an edge.

Is it because investors feel Ability has come up with some magic formula that will ensure its continued outperformance in its funds generally?

There is little data to suggest that you can objectively pick which mutual funds are going to outperform in future.

Is it because your financial adviser considers it a sound choice?

First figure out if the adviser has a financial incentive, like a cut of the fees, in giving you the advice. The world is moving towards greater clarity about how advisers get paid, making it easier to understand if there is a financial incentive in recommending some products. Keep in mind that comparison sites also get a cut of the often hefty active manager fees. Now consider if your adviser really has the edge required to make this active choice. Unless he has a long history of getting these calls right I would question whether he has the special edge that eludes most (and would he really share this incredibly unique insight if he had it?).

They have done so well in the past

Countless studies confirm that past performance is a poor predictor of future performance. If life was only so easy – you just pick the winners and away you go …

We are often driven by the urge to do something proactive to better our investment returns instead of passively standing by. And what better than investing with a strong performing manager from a reputable firm in a hot sector we have researched?

Mutual fund/unit trust charges vary greatly. Some charge up-front fees (though less frequently than in the past), but all charge an annual management fee and expenses (for things like audit, legal, etc.), in addition to the cost of making the investments. All-in costs span a wide range, but if you assume a total of 2.5% a year that is probably not too far out. So if someone manages $100 for you, the all-in costs of doing this will amount to approximately $2.5 a year come rain or shine.

If markets are steaming ahead and are up 20% or more every year, paying one-tenth to the well-known steward of your money may seem a fair deal. The trouble is that no markets are up 20% a year every year. We can perhaps expect equity markets to be on average up 4–5% a year above inflation. So you need to pick a mutual fund that will outperform the markets by 2%, before your costs, in order to be no worse off than if you had picked the index-tracking exchange traded fund (ETF), assuming ETF fees and expenses of 0.5% a year. (ETFs, which are investment products that are traded like normal stock, will be discussed later.)

You need to pick the best mutual fund out of 10 for it to make sense!

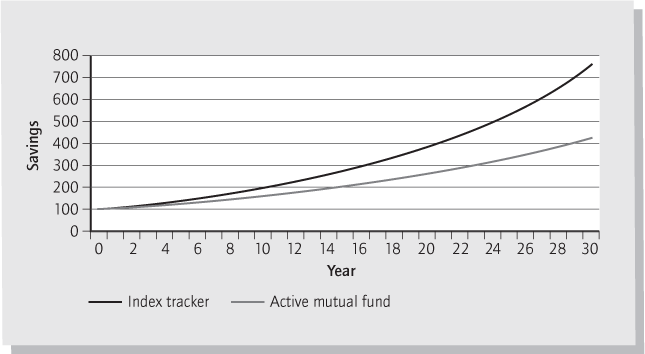

To give an idea of how much the fees impact over time consider the example of investing $100 for 30 years. Suppose the markets return 7% a year (a 5% real return plus 2% inflation would be a reasonable expectation – see later) and the difference becomes all too obvious over time – see Figure 2.1. (There is a 2% fee disadvantage in this mutual fund case compared to the tracker fund.)

Ability and its many competitors go to great lengths to show their data in the brightest light, but a convincing number of studies show that the average professional investor does not beat the market over time, but in fact underperforms by approximately the fee amount.

Figure 2.1 Index tracker versus mutual fund returns over 30 years

There is of course the possibility that you are somehow able to pick only the best-performing funds. Suppose you had $100 to invest in either an index tracker, or a mutual fund that had a cost disadvantage of 2% a year compared to the tracker. Suppose also that the market made a return of 7% a year for the next 10 years. Finally assume that the standard deviation1 of each mutual fund’s performance relative to the average mutual fund performance was 5% (the mutual funds predominantly own the same stocks as the index and their performance will be fairly similar as a result). Figure 2.2 shows the returns of an index tracker compared to 250 mutual funds with those inputs.

Comparing an actively managed portfolio to an index tracker is unfortunately not as simple as subtracting 2% from the index tracker to get to the actively managed return. The returns will vary from year to year, and in some years the actively managed fund will outperform the index it is tracking. Some funds will even outperform the index over the 10-year period. If you can pick the outperforming fund consistently, you have an edge. If you can’t, you should buy the index.

In approximately 90% of the cases in the 10-year example above, the index tracker would outperform the actively managed mutual fund, which is roughly in line with what historical studies suggest. So in order for it to make sense to pick a mutual fund over the index tracker you have to be able to pick the 10% best-performing mutual funds. That would be pretty impressive.

If you did not have an edge and blindly picked a mutual fund instead of the index tracker you would, on average, be about $30 worse off on your $100 investment after 10 years because of the higher costs. Had it been a $100,000 investment the difference would be enough to buy you a car.

You can bet your bottom dollar that the 10% of mutual funds that outperformed the index would trumpet their special skills in advertisements. Historical performance is, however, not only a poor predictor of future returns, but it can be very hard to distinguish between what has been chance (luck) and skill (edge). Just as one out of 1,024 coin flippers would come up heads 10 flips in a row, some managers would do better simply because of luck. In reality the odds are much worse in the financial markets as fees and costs eat into the returns. However, ask the manager who has outperformed five years in a row (every 50th coin flipper …) and she will disagree with the argument that she was just lucky, even as some invariably are. Likewise some managers underperform the market several years in a row simply due to bad luck, but those disappear from the scene and thus introduce a selection bias as only the winners remain. This sometimes makes the industry appear more successful than it has been.

Outside stock markets

The discussion of edge is not exclusive to stock markets. You can have an investment edge in many areas other than the stock market and profit greatly from that edge, for example:

- Will Greece default on its loans?

- Will the price of oil increase further?

- Will the USD/GBP exchange rate reach 2 again?

- Will the property market increase/decrease?

The list goes on …

Being rational

For someone to accept that they don’t have an edge is a key ‘eureka’ moment in their investing lives, and perhaps without knowing it at first, they will be much better off as a result. At this point you are at least hopefully considering a couple of things:

- An edge is hard to achieve and it’s important to be realistic about whether or not you have it.

- Conceding that you don’t have an edge is a sensible and very liberating conclusion for most investors. It makes life a lot easier (and wealthier) if you acknowledge that you can’t better the aggregate knowledge of a market swamped with thousands of experts that study Microsoft and the wider markets.

Have a look at Video 2 on Kroijer.com for a summary of the issues discussed in this chapter.

____________________

1 A standard measure of risk that gives an idea of the range of returns you could expect and with what frequency.