Adding government bonds to the rational portfolio

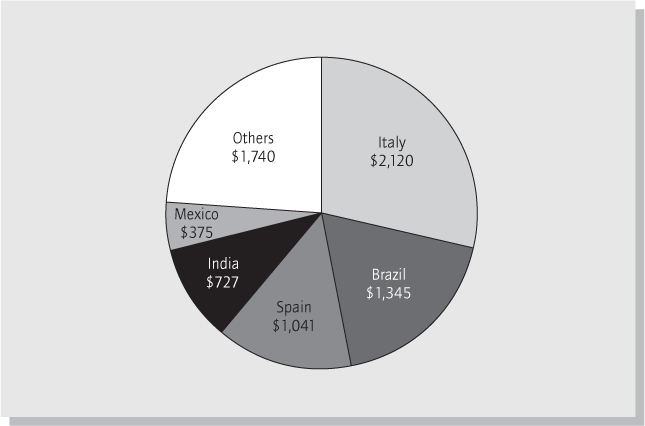

There are good reasons to add government bonds to your rational portfolio in addition to those you already hold as your minimal risk asset. Despite the world’s increasing international interdependence government bond portfolios are geographically diversified and a portfolio of them can therefore lower risk. Figure D.1 shows government debt by geographical sector.

It is probably not surprising to many that the US debt is right at the top, considering the size of its economy, but that Japan is there alongside it may surprise some. With its very large debt/GDP ratio of over 200% Japan has managed to remain very indebted, but without incurring high, real interest rates as a result.1

As with equities, when adding other government bonds we would normally try to invest as broadly and cheaply as possible, and allocate in accordance to the relative values that the market has already ascribed to the various securities. However, you should amend this and not buy other government bonds in the proportions of the bonds outstanding that are shown in Figure D.1.2

Figure D.1 Government debt in $ billions

Based on data from Bank for International Settlements, end quarter 2 2016, www.bis.org

Earlier, we discussed how a highly rated government bond in the right currency provided the best investment for risk-averse investors, albeit at very low interest rates (at the time of writing). As an example, if I’m a UK-based investor looking for the lowest-risk investment for the next five years in sterling, I should buy five-year UK government bonds, perhaps in the form of inflation-protected bonds.

As we are now considering adding other government and corporate bonds to the rational portfolio of minimal risk bonds and equities, we should not just blindly add all the world’s government bonds (see Figure D.2). We already have exposure to UK government bonds and therefore do not need to include more of these in the portfolio,3 we would just be doubling up on an exposure already taken to be the minimal risk investment.

How much the exclusion of the minimal risk asset from the world government bond portfolio changes the profile of the remaining portfolio depends on your base currency. If your base currency is $ or yen, then you would have reduced the universe of government bonds by a quarter. On the other hand, if your base currency is my native Danish kroner (with AAA-rated government bonds), then the impact on the world government bond portfolio would be negligible.

Only add government bonds if they increase expected returns

We discussed earlier how when adjusting for inflation investors in several highly rated government bonds should actually expect to earn a negative return, at least for short-term bonds. At the time of writing, the major countries with AAA or AA rating that offer a safe haven in their domestic currency but with little or no real return include Australia, Switzerland, Japan, Germany, the UK and the US, among others.

Consider the example of a sterling-based investor with US government bonds as her minimal risk portfolio, contemplating adding other government bonds to her rational portfolio. From the US bonds she gets almost no real returns, but also takes almost no risk. If she were to add bonds from the AAA- or AA-listed countries above she would also get no return, but would be taking currency risk. So she would get no greater returns from the foreign bonds, but take more risk.4

The rational investor thus has little to gain from adding AAA or AA government bonds to her portfolio other than as a minimal risk asset. If she was after a lower-risk portfolio she could add more of the minimal risk bonds (US government bonds in this example). If she was willing to accept more risk in the portfolio she could get additional expected returns by either adding equities or government bonds that had a higher real return expectation than that offered by her minimal risk asset.

One caveat to excluding the other AAA/AA government bonds from the rational portfolio (see Figure D.3): if you think there is credit risk in your minimal risk asset, then it may make sense to spread your investments among other AAA/AA credits. For example, if you are a US investor and don’t consider the US government’s credit entirely safe, then you could split your minimal risk investment into a couple of different AAA/AA bonds to diversify the credit. By diversifying you decrease the concentration risk of having your minimal risk asset from just one issuer (the US government in this case), although it means taking currency risk with the other government bond holdings.5

Figure D.3 Typically, do not add other AAA/AA credits

The government bonds we should add to the rational portfolio

If the above seems like excluding a lot of government bonds, remember that you have only removed those already in the portfolio (the minimal risk asset) and other government bonds without meaningful additional expected real return (but with currency risk).

After omitting the minimal risk asset and other AAA/AA government bonds because of their low yield, the bonds you should consider adding to your portfolio are real return-generating government bonds (the rest) and corporate bonds (see Figure D.4). And here we are still talking many trillions of dollars of potential investments.

Figure D.4 Add real return-generating government bonds to the portfolio

Figure D.5 Below AAA government debt in $ billions

Based on data from Bank for International Settlements, end quarter 2016, www.bis.org

Which government bonds you are left to invest in depends on how highly rated are the bonds that you want to eliminate. If you were only to eliminate bonds that were AAA rated and wanted to invest in the remaining then those would be distributed as shown in Figure D.5.

What you will notice is that this list is dominated by the US and Japan, ‘only’ AA+ rated and A+ rated by S&P at the time of writing, and thus not deemed entirely without risk. But if you, like most investors, take the view that these bonds still did not offer enough expected real return to be worth adding to the portfolio (besides being the minimal risk for investors in those currencies), and that you only wanted to add government bonds rated below AA (to get additional yield), then the remaining world government bonds would be distributed as shown in Figure D.6.

The way to read Figure D.6 would be as follows:

I am an investor who, in addition to my minimal risk asset and equity portfolio, wants to add a diversified group of other government bonds. Since I already have exposure to my minimal risk government bonds and don’t think government bonds from countries rated AAA/AA offer enough yield to be interesting, which government bonds should I be adding?

Figure D.6 Below AA government debt in $ billions

Based on data from Bank for International Settlements, end quarter 2 2014, www.bis.org

While in principle you should buy the bonds rated below AA according to their market values, in reality it is not practical for some investors to find investment products that represent so many different countries. Instead you might buy an emerging market government bond exchange traded fund (ETF) and combine that with a product covering sub-AA eurozone government bonds. The combination you end up with would not be exactly in the proportions of the sub-AA-rated bonds in Figure D.6, but get you a long way towards adding a diversified group of real return generating government bonds to your rational portfolio.

Bond yields move a lot. Even at the height of the 2008 financial crisis the yield on 10-year Greek government debt was 5–6% compared to the unsustainable levels a couple of years later. This was considered a safe investment although events since suggest that it wasn’t and provide a good example of how the credit quality of an individual government can decline at an alarming pace if the markets lose confidence in repayment. Despite the fact that the government bonds in the sub-AA chart (see Figure D.6) are geographically diversified investments, you should expect some correlation between them. Not only do some of the European countries operate in the same currency and open market (the EU), but all countries are subject to changes in the world economy, besides their unique domestic changes, and are similarly vulnerable to changes in market sentiment.

Table D.1 shows the yields on various selected 10-year government bonds that fit into the real return-generating government category at the time of writing. While the table below is for 10-year bonds only (you should try to get a mix of maturities) it gives you an idea of the interest you can expect from these lower-rated bonds.

These yields are in local currency-denominated bonds. Since the expected inflation on the Brazilian real is greater than that of the euro the inflation-adjusted return is not as high as suggested above. In other words, Brazil is not as poor a credit risk as suggested by the table.

In addition, it is unfair to say, for example, that you would expect to make a nominal 11.4% return from Brazilian bonds. The high return implies an increased probability that Brazil will default or that you will somehow not be paid in full.

There are some further points when considering adding other government bonds to the portfolio:

- As you add additional government bonds from these lower-rated countries do so in a range of maturities. On top of diversifying geographically this will avoid concentration of the interest rate risk. Practically, adding these bonds is best done via buying a range of ETFs or low-cost investment funds that buy the underlying bonds for a low fee. For example, you could buy an emerging markets bond ETF that will give you an underlying exposure to the wide range of lower-rated government bonds in different maturities that you are looking for. Likewise, with some of the sub-AA-rated developed country government bonds. By holding the bonds via ETFs or investment funds you don’t have to worry about buying new bonds as old ones mature. The provider will do this for you and ensure that your maturity profile remains fairly stable, which is what you want.

- Be careful that you don’t add concentration risk when you are meant to be diversifying. In Table D.1 (that excludes the AAA bonds only) if your minimal risk asset had been US bonds and thus excluded, Japanese bonds would have been over 50% of the remaining amount. These charts and tables should serve to remind you to broadly diversify your government bond holdings to those that add real returns – not increase concentration risk to one issuer (e.g. Japan).

- Buying the government bonds listed above in proportion to their shares of all sub-AA-rated government bonds would be an expensive administrative headache, and there are no access products like ETFs or index funds that do exactly that for you. But if you don’t get the proportions exactly right that is fine too. Perhaps buy some low-cost emerging market government bond funds and add to those some exposure to below-AA developed market government bond funds. If you do this roughly in proportion so that each country’s or region’s share is roughly similar to that of its share in Table D.1 then that is a good approximation.

- Keep an eye out for changes in the make-up of real return-generating government bonds. Some of the bonds rated lower than AA may have increased in credit quality to the point where they don’t really add real returns in excess of your minimal risk asset, or perhaps more likely some of the governments rated AA or above may have declined in credit quality to the point where they are worth adding as a real return generator. I look forward to re-reading this book in 10 years’ time and with the benefit of hindsight seeing which governments moved up or down in credit quality. Look to make these changes as you rebalance your portfolio occasionally. Since your real-return generating government bond portfolio is well diversified, changes to it will hopefully not be too dramatic, but likewise keep in mind that unlike the minimal risk asset, world equities and corporate bonds, this is the one segment of the rational portfolio where a broad-index-type access product like an ETF or index tracker will be unlikely to suit your needs. You probably have to put a few products together yourself to create a portfolio of sub-AA-rated government bonds, the make-up of which will change over time.

____________________

1 At the time of writing, shorting Japanese government debt is a popular hedge fund trade as the managers deem the debt levels unsustainable, but according to a Japanese hedge fund manager friend of mine the arguments used are hardly new and in his view this is not a ‘slam dunk’ trade. Time will tell.

2 As a first gut feel of why this ‘buy the world’ strategy may not work for everyone, consider that over half your government bond portfolio would be Japanese and US government bonds. This not only adds quite a bit of concentration risk to two issuers, but also adds currency risk and minimal real expected returns due to the low/negative real yields on those bonds.

3 One minor caveat to this argument: if the mix of maturities you added to get to your minimal risk asset is very different from the overall mix of maturities issued by that government then it makes sense to amend the minimal risk allocations. So if you only had very short-term bonds in your minimal risk allocation, yet are willing to add more risk in the form of equities and other bonds, it makes sense for this allocation to include some longer-term bond exposure from that same government.

4 There is of course the possibility that the other currencies appreciate against sterling. So if you held US bonds and the dollar went up in value relative to the pound, those bonds would be worth more in sterling terms. That being the case, although this risk can also lead to you making money it is not a risk you get compensated for taking in the form of higher expected returns.

5 By adding other safe bonds to your minimal risk bonds you are also diversifying your interest rate risk away from that of just one currency (you have exposure to a couple of different yield curves), but for the purposes of keeping the portfolio simple I don’t think this diversification is worth the added complexity and currency risk of those bonds.