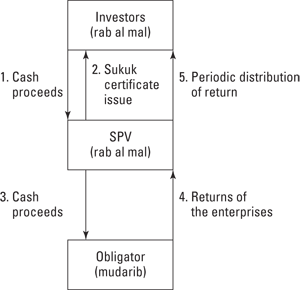

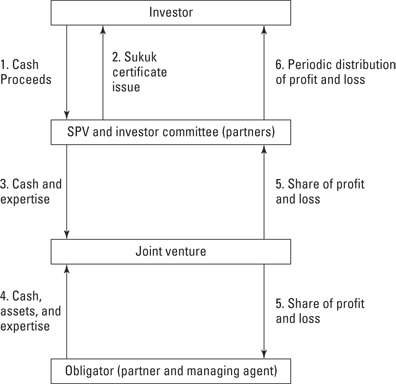

Figure 13-1: Sukuk based on the mudaraba contract.

Chapter 13

Investing in Islamic Bonds: Sukuk

In This Chapter

![]() Contrasting sukuk and conventional bonds

Contrasting sukuk and conventional bonds

![]() Finding out how sukuk are traded, rated, and issued

Finding out how sukuk are traded, rated, and issued

![]() Scouting sukuk products

Scouting sukuk products

![]() Tracing the sukuk market’s evolution

Tracing the sukuk market’s evolution

As I note in Chapter 11, the Islamic capital market features various investment instruments that fall into two broad categories: sharia-compliant equities and sukuk, or Islamic bonds. In this chapter, I focus on sukuk, which comprise one of the fastest growing segments in both the Islamic and global financial industries.

Government and corporate issues from both Muslim and non-Muslim countries are driving the growth of sukuk. At the end of 2011, outstanding sukuk were valued at an estimated $182 billion and growing at a rate of 30 percent per year.

In this chapter, I explain what sukuk are and how they differ (significantly) from conventional bonds. I then describe how sukuk are traded, rated, and issued and cover the structure and issuance of specific types of sukuk products. Finally, I take a quick look at the size and projected growth of the global sukuk market.

Defining Sukuk

Before I explain the product, I want to define the word itself. Sukuk is the plural form of the Arabic word sakk, which means “certificate” or “written document.” (A fun bit of trivia: Some experts say the word check may derive from the Arabic work sakk.) As I explain in Chapter 3, sukuk have a long history; they were used in the Middle Ages by Muslims to represent financial obligations that originated from commercial activities. Modern-day sukuk differ from the historical sukuk; Muslims in the Middle Ages certainly didn’t have access to the broad spectrum of sukuk products that exist on the market today.

The Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB) defines sukuk this way:

Sukuk . . . are certificates with each sakk representing a proportional undivided ownership right in tangible assets, or a pool of predominantly tangible assets, or a business venture. These assets may be in a specific project or investment activity in accordance with Sharia rules and principles.

The Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) defines sukuk as “certificates of equal value representing undivided shares in ownership of tangible assets, usufruct, and services.” Usufruct is the right to earn profit from property owned by another person or from property that has common ownership. Common or collective ownership refers to a situation in which many people own an asset, such as land. For example, if a tribe or family has common ownership of a piece of land, then the asset isn’t public property and no individual can claim ownership of any part of the land (and therefore can’t sell even a small piece without consent from the rest of the owners).

Clear as mud? Don’t worry; in this section, I help you parse these definitions by first identifying the key characteristics of conventional bonds and then providing an overview of sukuk characteristics and comparing the two financial products.

Reviewing how conventional bonds work

Conventional bonds are debt instruments. The government, corporation, or other entity issuing a conventional bond essentially sells IOUs to investors. Each bond has a face amount or a par value, which is often $1,000. The investor pays that amount or, depending on the state of the bond market at the time of purchase, may pay a premium (more than par value) or a discount (less than par value).

To allow for an easy comparison between conventional bonds and sukuk, I next present three key pieces of information about conventional bonds: how they reward investors, how they are repurchased at their maturity dates, and why they don’t comply with Islamic law.

Rewarding investors for conventional bonds

The conventional investor receives interest payments as a reward for a bond purchase; this interest may be based on a fixed interest rate for the life of the bond or may be adjustable. The issuer usually sends interest payments to the investor twice a year.

Repurchasing conventional bonds at maturity

Each bond is issued with a specific date of maturity — the date when the bond’s term is complete. On that date, the issuer owes the investor the initial face value of the bond; the principal is guaranteed by the issuer no matter how well the underlying investment performs. So the investor gets his principal back and in the meantime receives interest for letting the issuer use his money.

Identifying the sharia-related problems with conventional bonds

![]() Bonds pay investors based on fixed or adjustable interest rates.

Bonds pay investors based on fixed or adjustable interest rates.

![]() Investors also earn money by purchasing the bonds at less than their face value and/or selling them at higher than their face value. (The market price of a bond is directly related to interest rates and may be higher or lower than the bond’s face value.)

Investors also earn money by purchasing the bonds at less than their face value and/or selling them at higher than their face value. (The market price of a bond is directly related to interest rates and may be higher or lower than the bond’s face value.)

For a primer on sharia compliance and why interest-based activities are prohibited in the Islamic financial system, check out Chapters 1 and 5.

Realizing how sukuk differ

Modern sukuk emerged to fill a gap in the global capital market. Islamic investors want to balance their equity portfolios with bond-like products. Because sukuk are asset-based securities — not debt instruments — they fit the bill. In other words, sukuk represent ownership in a tangible asset, usufruct of an asset, service, project, business, or joint venture. For simplicity’s sake, I use the word asset to refer to this list of entities on which a sukuk may be based.

Each sukuk has a face value (based on the value of the underlying asset), and the investor may pay that amount or (as with a conventional bond) buy it at a premium or discount.

As I did for conventional bonds in the preceding section, I next describe the investor rewards related to sukuk, what happens when a sukuk matures, and how sharia compliance comes into play.

Rewarding investors for sukuk

With sukuk, the future cash flow from the underlying asset is transferred into present cash flow. Sukuk may be issued for existing assets or for assets that will exist in the future. Investors who purchase sukuk are rewarded with a share of the profits derived from the asset. They don’t earn interest payments because doing so would violate sharia.

Repurchasing sukuk at maturity

As with conventional bonds, sukuk are issued with specific maturity dates. When the maturity date arrives, the sukuk issuer buys them back (through a middleman called a Special Purpose Vehicle, which I explain in the later section “Walking through the Process of Issuing Sukuk”).

Most sharia scholars believe that having sukuk managers, partners, or agents promise to repurchase sukuk for the face value is unlawful. Instead, sukuk are generally repurchased based on the net value of the underlying assets (each share receiving its portion of that value) or at a price agreed upon at the time of the sukuk purchase.

Ensuring sharia compliance with sukuk

The key characteristic of sukuk — the fact that they grant partial ownership in the underlying asset — is considered sharia-compliant. This ruling means that Islamic investors have the right to receive a share of profits from the sukuk’s underlying asset.

Putting bonds and sukuk side-by-side

When you have the basics about how conventional bonds and sukuk work, it’s time to put them next to each other. Table 13-1 offers a quick look at the key ways in which these investment products compare.

Table 13-1 Distinguishing Sukuk from Conventional Bonds

|

Conventional Bonds |

Sukuk |

|

|

Bonds don’t give the investor a share of ownership in the asset, project, business, or joint venture they support. They’re a debt obligation from the issuer to the bond holder. |

Sukuk give the investor partial ownership in the asset on which the sukuk are based. |

Asset ownership |

|

Generally, bonds can be used to finance any asset, project, business, or joint venture that complies with local legislation. |

The asset on which sukuk are based must be sharia-compliant. |

Investment criteria |

|

Each bond represents a share of debt. |

Each sukuk represents a share of the underlying asset. |

Issue unit |

|

The face value of a bond price is based on the issuer’s credit worthiness (including its rating). |

The face value of sukuk is based on the market value of the underlying asset. |

Issue price |

|

Bond holders receive regularly scheduled (and often fixed rate) interest payments for the life of the bond, and their principal is guaranteed to be returned at the bond’s maturity date. |

Sukuk holders receive a share of profits from the underlying asset (and accept a share of any loss incurred). |

Investment rewards and risks |

|

Bond holders generally aren’t affected by costs related to the asset, project, business, or joint venture they support. The performance of the underlying asset doesn’t affect investor rewards. |

Sukuk holders are affected by costs related to the underlying asset. Higher costs may translate to lower investor profits and vice versa. |

Effects of costs |

(Usually) Trading Sukuk Like Conventional Bonds

Most sukuk, like most conventional bonds, are bought and sold in the over-the-counter (OTC) market, where potential yields, maturities, and risk factors affect price. The OTC market includes the following players:

![]() Dealers: These people maintain databases that list the sukuk and conventional bonds available for sale and purchase.

Dealers: These people maintain databases that list the sukuk and conventional bonds available for sale and purchase.

![]() Brokers and agents: These individuals purchase and sell sukuk and conventional bonds on behalf of their customers according to customer specifications.

Brokers and agents: These individuals purchase and sell sukuk and conventional bonds on behalf of their customers according to customer specifications.

![]() Banks, insurers, and/or investment houses: These large institutions trade sukuk and conventional bonds per broker/agent orders.

Banks, insurers, and/or investment houses: These large institutions trade sukuk and conventional bonds per broker/agent orders.

Initially, sukuk and conventional bonds are issued in the primary market, which refers to the part of the capital markets where new issues are bought and sold; the investor gets the sukuk or conventional bonds directly from the issuer. Then, sukuk and conventional bonds are sold in the secondary market, where an investor purchases them from another investor (not directly from the issuer).

When sukuk and conventional bonds are sold in the OTC market, their prices are based on the dealer’s cost plus markup. The type of sukuk or bond and the size of the total transaction play into the price.

In the conventional system, some corporate bonds are also listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Likewise, a growing trend with sukuk is that they’re being traded in exchanges, including the following:

![]() The Indonesia Stock Exchange (IDX)

The Indonesia Stock Exchange (IDX)

![]() The Bursa Malaysia exchange

The Bursa Malaysia exchange

![]() Tadawul (the Saudi Stock Exchange)

Tadawul (the Saudi Stock Exchange)

![]() The London Stock Exchange (LSE)

The London Stock Exchange (LSE)

![]() The Luxembourg Stock Exchange

The Luxembourg Stock Exchange

![]() The Irish Stock Exchange (ISE)

The Irish Stock Exchange (ISE)

![]() NASDAQ Dubai

NASDAQ Dubai

Earning Credit Quality Ratings

Conventional bonds are rated by international, independent, private rating agencies such as Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s, and Fitch to express the credit quality of the bonds. These rating institutions consider the issuer’s financial strength, ability to repay the principal, and ability to adhere to scheduled interest payments to investors. Both corporate and government (sovereign) bonds receive credit quality ratings.

The conventional rating agencies also rate sukuk based on their credit quality and the issuer’s ability to pay investors. Sukuk receive ratings that look exactly like those applied to conventional bonds. For example

![]() The highest quality sukuk are rated Aaa by Moody’s, AAA by Standard & Poor’s, and AAA by Fitch.

The highest quality sukuk are rated Aaa by Moody’s, AAA by Standard & Poor’s, and AAA by Fitch.

![]() Intermediate quality sukuk may be rated Ba by Moody’s, BB by Standard & Poor’s, and BB by Fitch. (Other intermediate ratings apply.)

Intermediate quality sukuk may be rated Ba by Moody’s, BB by Standard & Poor’s, and BB by Fitch. (Other intermediate ratings apply.)

![]() Sukuk that are toward the bottom of the ratings scale (meaning they’re very risky investments that may not return much to investors) may receive ratings of Caa from Moody’s, CCC from Standard & Poor’s, and CCC from Fitch. (Even worse ratings exist, of course, including those applied to sukuk and conventional bonds that are in default.)

Sukuk that are toward the bottom of the ratings scale (meaning they’re very risky investments that may not return much to investors) may receive ratings of Caa from Moody’s, CCC from Standard & Poor’s, and CCC from Fitch. (Even worse ratings exist, of course, including those applied to sukuk and conventional bonds that are in default.)

At first glance, you may think that such ratings are a boon to the sukuk industry; if Western investors see a sukuk product with an Aaa rating from Moody’s, they may be willing to invest even though the product is less familiar to them than a conventional bond. But because sukuk are so different from conventional bonds, some people criticize the fact that conventional bond rating agencies also rate sukuk. Doing so sets up a comparison between sukuk and conventional bonds that’s potentially misleading to investors; these products differ so greatly. In other words, if an investor doesn’t know as much about sukuk as you already do — if she hasn’t read information in this chapter and realized that sukuk are asset-based products with rewards based on the asset(s) generating profit — she may make an investment decision that isn’t fully informed.

In addition to the big three ratings institutions, sukuk may be rated by other agencies. Two Malaysia-based ratings agencies (which have rating systems for both conventional and Islamic capital market instruments) are the largest and best-known: RAM Rating (www.ram.com.my) and MARC, the Malaysian Rating Corporation Berhad (www.marc.com.my).

Walking through the Process of Issuing Sukuk

Issuing sukuk is similar to issuing conventional bonds. Consider how simple, conventional corporate bond issues work:

1. The company structures the bonds with its board’s approval, specifying the face amounts, interest rates, and maturity date and determining how many bonds it plans to issue (indicating how much money it hopes to raise).

2. The company prepares the bond prospectus, which explains the bond specifics to potential investors.

3. The company contracts an underwriter (a large financial institution, such as a bank, insurer, or investment house) to conduct the bond issuance. The underwriter offers insurance to the issuer that it will purchase any bonds that investors don’t buy.

4. The underwriter acts as middleman, selling bonds to investors on behalf of the corporation.

Although a sukuk issuance goes through a similar procedure, different types of sukuk products require different structures. Therefore, the first step of the process is unique to the specific sukuk product. (I describe some specific sukuk products in “Listing Types of Sukuk” later in this chapter.) Also, sukuk require the creation of an intermediary called a Special Purpose Vehicle, which I explain in “Creating the SPV for acquiring assets.”

In this section, I explain who is involved in issuing sukuk, what’s involved in establishing the general sukuk structure, who the middlemen are in a sukuk issuance, and the function of an underwriter.

Identifying the parties involved

Any sukuk issue involves three main parties; an optional fourth party (the underwriter) may or may not come on board:

![]() Obligator: The obligator is the government or corporation that is going to benefit from the sukuk issuance.

Obligator: The obligator is the government or corporation that is going to benefit from the sukuk issuance.

![]() Trustee or issuer: This party, called the Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), is the middleman between the obligator and the investors.

Trustee or issuer: This party, called the Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), is the middleman between the obligator and the investors.

![]() Investors: These entities are the sukuk holders.

Investors: These entities are the sukuk holders.

![]() Underwriter: With sukuk, an underwriter doesn’t usually conduct the actual bond issuance and isn’t required in every situation. However, an underwriter may be brought in as insurance to the SPV, to guarantee that any unsold sukuk will be purchased. The leading conventional banks or their Islamic subsidiaries (for example, HSBC Amanah, CIMB Investment Bank, and Standard Chartered Bank) are most often the underwriters for sukuk.

Underwriter: With sukuk, an underwriter doesn’t usually conduct the actual bond issuance and isn’t required in every situation. However, an underwriter may be brought in as insurance to the SPV, to guarantee that any unsold sukuk will be purchased. The leading conventional banks or their Islamic subsidiaries (for example, HSBC Amanah, CIMB Investment Bank, and Standard Chartered Bank) are most often the underwriters for sukuk.

Unlike conventional bonds, which are issued via an underwriter (such as an existing bank, insurer, or investment house), sukuk usually require the obligator to create a new entity, an SPV, to act as trustee or issuer. In the upcoming section “Creating the SPV for acquiring assets,” I explain what an SPV is. (Hint: It’s not the latest spinoff in the Law & Order franchise.)

In the simplest form, here’s how the three key parties in a sukuk issuance interact:

1. The obligator creates or contracts the SPV to act on its behalf during a sukuk issuance. The obligator and SPV enter a sukuk-specific contract, and the obligator specifies the asset or activity the sukuk will support, as well as other particulars about the issuance (the face value, maturity, and so on).

1. The obligator creates or contracts the SPV to act on its behalf during a sukuk issuance. The obligator and SPV enter a sukuk-specific contract, and the obligator specifies the asset or activity the sukuk will support, as well as other particulars about the issuance (the face value, maturity, and so on).

2. The SPV issues the sukuk to the investors. Each sukuk subscription involves an agreement that spells out the relationship between the obligator and sukuk holders (as lessor and lessee, partners in a venture, principal and agent to manage investments, and so on) and the nature of the income/gain that the investors are entitled to (such as rental income or what portion of the obligator’s profit or loss the investor will share).

3. The SPV gives the proceeds from the investors to the obligator. The proceeds are to be used for the sharia-compliant asset purchase, lease, joint venture, or other business activity agreed upon between the obligator and sukuk holder during the sukuk issuance.

4. The SPV distributes the obligator’s returns or losses to the investors. The income or share of profits or losses borne by each investor is based on the agreement entered with the obligator.

The following sections explore the first two steps of this process in a bit more detail.

Setting up the sukuk’s general structure

The first step in issuing sukuk is setting up their general structure. The obligator (issuing government or corporation) gets the help of sukuk arrangers to complete this step. Arrangers are Islamic financial service providers and professionals who know the sukuk process. (If a sukuk underwriter is needed, the arranger usually fills that role as well.) For this step, the obligator must describe the following:

![]() Purpose of the sukuk: The purpose refers to the underlying asset (which can be a tangible asset, project, joint venture, and so on) set to directly benefit from the issuance.

Purpose of the sukuk: The purpose refers to the underlying asset (which can be a tangible asset, project, joint venture, and so on) set to directly benefit from the issuance.

![]() Legal issues/relevant regulations: When conventional bonds are issued, they must be approved by the regulatory authorities of the countries in which they’re to be publicly issued (or listed in exchanges). In the same way, sukuk need to be approved by the relevant authorities for public offerings.

Legal issues/relevant regulations: When conventional bonds are issued, they must be approved by the regulatory authorities of the countries in which they’re to be publicly issued (or listed in exchanges). In the same way, sukuk need to be approved by the relevant authorities for public offerings.

A public sukuk offering in Saudi Arabia, for example, needs to be approved by the Capital Market Authority of Saudi Arabia. The Security Commission of Malaysia needs to approve sukuk that will be listed in its exchange.

A public sukuk offering in Saudi Arabia, for example, needs to be approved by the Capital Market Authority of Saudi Arabia. The Security Commission of Malaysia needs to approve sukuk that will be listed in its exchange.

The sukuk structure must include language that explains which regulatory approvals are required. In addition, it must describe the legal status of the SPV (the sukuk trustee/issuer).

![]() Information about the obligator: This description of the obligator must include what type of business it conducts and its historical performance along with a list of its board of directors and its outstanding shares.

Information about the obligator: This description of the obligator must include what type of business it conducts and its historical performance along with a list of its board of directors and its outstanding shares.

![]() Units: This description documents the number of sukuk involved in the issuance.

Units: This description documents the number of sukuk involved in the issuance.

![]() Currency: The currency of the sukuk transactions in the primary market must be specified.

Currency: The currency of the sukuk transactions in the primary market must be specified.

![]() Structure: This part details the Islamic contract on which the sukuk functions. It explains whether the issue is based, for example, on an ijara, musharaka, or mudaraba contract (which I explain later in the chapter).

Structure: This part details the Islamic contract on which the sukuk functions. It explains whether the issue is based, for example, on an ijara, musharaka, or mudaraba contract (which I explain later in the chapter).

The obligator (just like a conventional bond issuer) must then create a prospectus, which includes the general structure information as well as the following:

![]() The obligator’s rating per the independent rating agencies.

The obligator’s rating per the independent rating agencies.

![]() Risk factors related to the sukuk issuer (the SPV), to the obligator, or to the sukuk trust certificates themselves. Examples include the absence of a secondary market, the potential early redemption of trust certificates in certain cases, potential taxation issues, and potential legal issues (if the law were to change to become unfavorable to sukuk).

Risk factors related to the sukuk issuer (the SPV), to the obligator, or to the sukuk trust certificates themselves. Examples include the absence of a secondary market, the potential early redemption of trust certificates in certain cases, potential taxation issues, and potential legal issues (if the law were to change to become unfavorable to sukuk).

![]() The ownership of the issuer (the SPV).

The ownership of the issuer (the SPV).

![]() Names and affiliations of the administrators of the SPV and the sukuk arrangers.

Names and affiliations of the administrators of the SPV and the sukuk arrangers.

![]() Names and affiliations of the sharia advisors or board charged with ensuring that the sukuk issue complies with Islamic law.

Names and affiliations of the sharia advisors or board charged with ensuring that the sukuk issue complies with Islamic law.

![]() Dissolution issues, such as how the issuer redeems the sukuk trust certificates at the maturity date.

Dissolution issues, such as how the issuer redeems the sukuk trust certificates at the maturity date.

![]() A diagram of the sukuk structure and its cash flows.

A diagram of the sukuk structure and its cash flows.

![]() The terms and conditions of the trust certificates.

The terms and conditions of the trust certificates.

![]() Organizational information about the obligator, such as its shareholders, board of directors, and employees (including an organizational chart).

Organizational information about the obligator, such as its shareholders, board of directors, and employees (including an organizational chart).

![]() An introduction to the obligator’s industry.

An introduction to the obligator’s industry.

![]() Transaction documents and taxation issues.

Transaction documents and taxation issues.

Creating the SPV for acquiring assets

With the prospectus in hand, the obligator creates an SPV as a tool to acquire the sukuk’s underlying assets on behalf of the investors. An SPV may also be known by other names, including Special Purpose Entity (SPE) and Special Purpose Company (SPC).

The SPV is a legal entity that’s separate from the obligator and that manages the pool of assets related to the sukuk. SPVs are created to transfer the ownership of the asset, project, or business (because it’s not possible to transfer ownership directly to the individual sukuk holders). SPVs take legal ownership of the assets on which the sukuk are based.

The SPV is an intermediary between the investors and obligator. Naturally, an intermediary adds costs to the transaction. To keep these costs to a minimum, the SPV should be both tax-efficient and capital-efficient, meaning it should provide the best service possible for the least amount of money. SPVs are usually registered in tax-efficient jurisdictions such as Bahrain, Luxembourg, and the Cayman Islands.

![]() In 2009, Petronas of Malaysia issued sukuk via an SPV called Petronas Global Sukuk Ltd.

In 2009, Petronas of Malaysia issued sukuk via an SPV called Petronas Global Sukuk Ltd.

![]() East Cameron Partners in Houston, Texas, issued sukuk in 2006 by using the East Cameron Gas Company–Grand Cayman (Cayman Islands) as the SPV.

East Cameron Partners in Houston, Texas, issued sukuk in 2006 by using the East Cameron Gas Company–Grand Cayman (Cayman Islands) as the SPV.

![]() Dubai-based Nakheel Holdings issued sukuk via an SPV called Nakheel Development Ltd.

Dubai-based Nakheel Holdings issued sukuk via an SPV called Nakheel Development Ltd.

Insuring sukuk purchases

After the sukuk structure and the SPV are in place (see the preceding sections), the sukuk issuance begins. An underwriter may insure the sukuk issuance, promising the SPV to buy all the unsold sukuk. (In some cases, the underwriter may also serve as the sukuk issuer to the primary market.)

Listing Types of Sukuk

In Chapter 12, I explain that Islamic business contracts provide the basis for Islamic investment funds. Various types of sukuk also use these contracts, as I explain in the following sections.

Sukuk al mudaraba (sukuk based on equity partnership)

As I explain in Chapter 10, in simple mudaraba contracts, investors are considered to be silent partners (rab al mal), and the party who utilizes the funds is the working partner (mudarib). The profit from the investment activity is shared between both parties based on an initial agreement. (Any loss incurred is absorbed solely by the investors unless the working partner has been negligent in some way. The working partner loses the value of the time and effort it has devoted to the investment.)

The same type of contract applies to sukuk. In a mudaraba sukuk, the sukuk holders are the silent partners, who don’t participate in the management of the underlying asset, business, or project. The working partner is the sukuk obligator. What about the SPV? It’s also a silent partner of the mudaraba contract because it represents the sukuk holders (investors). The SPV pools the funds from the investors and acts on their behalf, so in essence the SPV is owned by the sukuk holders.

The sukuk obligator, as the working partner, is generally entitled to a fee and/or share of the profit, which is spelled out in the initial contract with investors. (The contract may refer the investor to the prospectus for information about how the originator is to be paid.)

The whole process begins when the SPV (acting in the capacity of the rab al mal on behalf of the investors) and the obligator (who wants to have capital for business) sign a mudaraba contract. In the contract, the SPV agrees to pay capital (the principal collected from the investors) to the obligator in support of a sharia-compliant asset or business activity. Generally, this agreement is a restricted mudaraba contract (meaning that the obligator can make investments only in the specific business mentioned); the prospectus spells out this designation.

Here’s how sukuk based on the signed mudaraba contract work (and see Figure 13-1 for a diagram of these steps):

1. The investors subscribe to the sukuk and pay proceeds to the SPV, which acts as their trustee.

2. The SPV issues sukuk certificates to the investors.

3. The obligator (the mudarib) receives the proceeds from the sukuk holders (investors).

4. The profits from the venture are divided between the obligator and the SPV, using predetermined (contractual) ratios. (Note that the obligator also may receive a management fee per the contract.)

5. The SPV receives the profits from the obligator and holds them. These profits are distributed among the sukuk holders on a periodic basis (again, per the contract).

Sukuk al murabaha (cost plus or deferred payment sukuk)

A murabaha contract is an agreement between a buyer and seller for the delivery of an asset; the price includes the cost of the asset plus an agreed-upon profit margin for the seller. The buyer can pay the price on the spot or establish deferred payment terms (paying either in installments or in one future lump sum payment).

With sukuk that are based on the murabaha contract, the SPV can use the investors’ capital to purchase an asset and sell it to the obligator on a cost-plus-profit-margin basis. The obligator (the buyer) makes deferred payments to the investors (the sellers). This setup is a fixed-income type of sukuk, and the SPV facilitates the transaction between the sukuk holders and the obligator.

To work around these issues, murabaha sukuk are issued in mixed portfolios (meaning portfolios that also feature other types of Islamic contracts). Some sharia scholars agree that if more than 50 percent of the portfolio’s fixed assets or ijara contracts are tied to murabaha sukuk, the entire portfolio may be issued as negotiable certificates and tradable on the secondary market.

The murabaha contract process begins with the obligator (who needs an asset but can’t pay for it right now) signing an agreement with the SPV to purchase the asset on a deferred-payment schedule. This agreement describes the cost-plus margin and deferred payments.

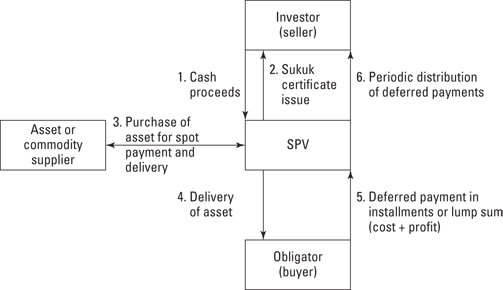

After the contract is signed, here’s how sukuk based on murabaha contracts work (and see Figure 13-2 for a diagram of these steps):

1. The investors subscribe to the sukuk and pay the proceeds to the SPV, which acts as their trustee.

2. The SPV issues sukuk certificates to the investors.

3. The SPV purchases the asset from a supplier.

4. The SPV sells the asset to the obligator per the contract terms. The delivery takes place on the spot.

5. The obligator pays the deferred payment to the SPV in a lump sum or installments.

6. The SPV distributes the deferred payments to the sukuk holders.

Figure 13-2: Sukuk based on the murabaha contract.

Sukuk al-salam (deferred delivery purchase sukuk)

In a salam contract, an asset is delivered to a buyer on a future date in exchange for full advance spot payment to the seller. As I note in Chapter 10, sharia allows only salam and istisna contracts to be used to support advanced payment for a good to be delivered in the future. This same mechanism is used for structuring the salam sukuk.

In salam sukuk, the sukuk holders’ (investors’) funds are used to purchase assets from an obligator in the future. The SPV provides the money to the obligator. This contract requires an agent (which may be a separate underwriter) who will sell the future assets because the investors want money in return for their investment — not the assets themselves. The proceeds from the sale (typically the cost of the assets plus a profit) are returned to the sukuk holders. Salam sukuk are used to support a company’s short-term liquidity requirements.

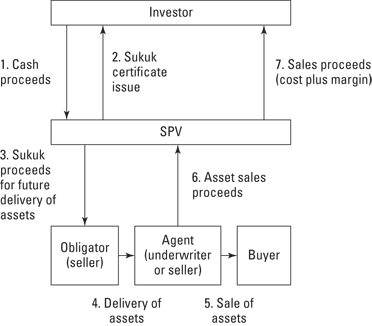

The first step in the process is that the SPV signs an agreement with the obligator saying that the SPV will buy the asset from the seller on the future date in exchange for advance payments. Then the process follows these steps (illustrated in Figure 13-3):

Figure 13-3: Sukuk based on the salam contract.

1. The investors subscribe to the sukuk and pay the proceeds to the SPV, which acts as their trustee.

2. The SPV issues sukuk certificates to the investors.

3. The proceeds from the sukuk sales are passed to the obligator (the seller).

At this stage, the SPV appoints an agent to sell the asset in the future for its cost plus a profit margin. This agent may be a separate underwriter, or it may be the obligator itself.

At this stage, the SPV appoints an agent to sell the asset in the future for its cost plus a profit margin. This agent may be a separate underwriter, or it may be the obligator itself.

4. On or before the date established in the contract, the seller delivers the asset to the underwriter or agent (if not the seller).

5. The underwriter, agent, or seller-as-agent sells the asset to a buyer for a profit.

6. The sales from the asset are transferred to the SPV.

7. The SPV distributes the proceeds to the sukuk holders (investors).

Because the sukuk holders receive the proceeds at the sukuk maturity, this investment product is similar to zero-coupon bonds. (In a different type of salam contract, the sukuk holder may receive periodic payments instead.)

Sukuk al-ijara (lease-based sukuk)

The ijara contract is essentially a rental or lease contract: It establishes the right to use an asset for a fee. The basic idea of ijara sukuk is that the sukuk holders (investors) are the owners of the asset and are entitled to receive a return when that asset is leased.

In this scenario, the SPV receives the sukuk proceeds from the investors; in return, each investor gets a portion of ownership in the asset to be leased. The SPV buys the title of the asset from the same company that is going to lease the asset. In turn, the company pays a rental fee to the SPV.

The ijara contract process begins when a company that needs an asset but can’t afford to purchase it outright contracts with an SPV, which agrees to purchase the asset and rent it to the company for a fixed period of time.

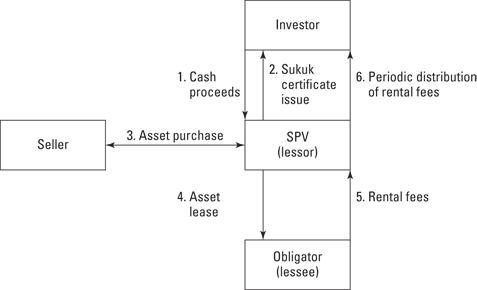

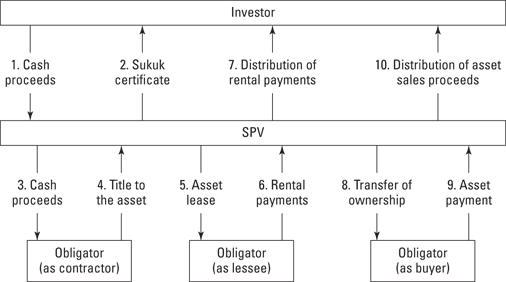

After the contract is signed, here’s how ijara sukuk work (Figure 13-4 shows you a diagram of the steps):

Figure 13-4: Sukuk based on the ijara contract.

1. Investors subscribe to the sukuk and pay the proceeds to the SPV, which acts as trustee.

2. The SPV issues sukuk certificates to the investors.

3. The SPV purchases the asset from a seller using investor proceeds.

4. The SPV leases the asset to the obligator.

5. The company (obligator) pays rental fees to the SPV.

6. The SPV distributes the rental fees to the investors according to the sukuk payment schedule.

Sukuk al musharaka (joint venture sukuk)

The musharaka contract supports a joint venture business activity in which all partners contribute capital, labor, and expertise. The profit and losses are shared among all parties based on agreed-upon ratios.

With musharaka sukuk, the sukuk holders (investors) are the owners of the joint venture, asset, or business activity and therefore have the right to share its profits. In a musharaka sukuk, unlike sukuk based on mudaraba, a committee of investor representatives participates in the decision-making process. Musharaka sukuk can be traded in the secondary market.

The musharaka sukuk process begins when an obligator signs a musharaka contract with the SPV that specifies a profit-sharing ratio and indicates that the obligator will transfer assets (such as cash and property) to the joint venture. Then the following occurs, as Figure 13-5 illustrates:

1. The investors subscribe to the sukuk and pay the proceeds to the SPV, which acts as the investors’ trustee.

2. The SPV issues sukuk certificates to the investors.

3. The SPV transfers the proceeds from the sukuk to the joint venture, and the investor committee contributes its expertise.

4. The obligator transfers cash and/or assets to the joint venture, and it also contributes its expertise.

5. The profit and loss of the joint venture is shared between the SPV and the obligator based on the contract agreement.

6. If the venture is profitable, the SPV distributes its share of profits from the joint venture to the sukuk holders at periodic intervals specified in the contract.

Figure 13-5: Sukuk based on the musharaka contract.

Sukuk al istisna (Islamic project bond)

As I explain in Chapter 10, istisna is a contract between a buyer and a manufacturer in which the manufacturer agrees to complete a construction project by a future date. The contract requires a fixed price and product specifications that both parties agree to. If the end product doesn’t meet contract specifications, the buyer can withdraw from the contract.

Istisna sukuk are based on this type of contract. The sukuk holders are the buyers of the project, and the obligator is the manufacturer. The obligator agrees to manufacture the project in the future and deliver it to the buyer, who (based on a separate ijara contract) will lease the asset to another party for regular payments.

The process of issuing istisna sukuk begins when the obligator (manufacturer or contractor) and the SPV sign an istisna contract. After that, the istisna sukuk work as follows (see Figure 13-6 for a diagram of these steps):

1. The investors subscribe to the sukuk and pay the proceeds to the SPV, which acts as their trustee.

2. The SPV issues sukuk certificates to the investors.

3. The proceeds from the sukuk issues are transferred to the obligator (in the role of manufacturer or contractor) in stages according to the agreed-upon payment schedule.

The obligator and SPV may sign another contract: a forward lease contract. If they do, the obligator (in a lessee role) begins making rental payments to the SPV even before the project is complete, and the SPV distributes the income to the sukuk holders. Note that this scenario isn’t represented in Figure 13-6.

The obligator and SPV may sign another contract: a forward lease contract. If they do, the obligator (in a lessee role) begins making rental payments to the SPV even before the project is complete, and the SPV distributes the income to the sukuk holders. Note that this scenario isn’t represented in Figure 13-6.

4. After the full project is complete, the title of the asset is transferred to the SPV.

5. The SPV leases the asset to the obligator.

6. The obligator (as lessee) makes rental payments to the SPV.

7. The SPV distributes the rental payments to investors at regular intervals.

8. At the sukuk maturity date, the asset ownership transfers to the obligator. In other words, the SPV sells the project to the obligator.

9. The obligator (now in the role of buyer) pays the SPV for the asset ownership.

10. Sale proceeds are distributed among the sukuk holders.

Figure 13-6: Sukuk based on the istisna contract.

Innovative sukuk

The preceding sections describe only very general sukuk structures based on Islamic business contracts. But many other forms of sukuk are available in the Islamic capital markets. Each country and corporation may develop innovative sukuk structures based on its requirements; as long as the country or corporation gets the approval of a sharia board, it can move forward with new and creative types of sukuk. However, the sharia compatibility of such products may be (and often is) called into question because not all sharia scholars share the same opinions on new financial products.

Here are just a few examples of innovative sukuk structures:

![]() Hybrid sukuk are based on different combinations of existing Islamic contracts such as those I cover in this chapter.

Hybrid sukuk are based on different combinations of existing Islamic contracts such as those I cover in this chapter.

![]() Islamic exchangeable bonds (or convertible sukuk) allow investors to convert their sukuk holdings into equity shares of the company that issued the sukuk.

Islamic exchangeable bonds (or convertible sukuk) allow investors to convert their sukuk holdings into equity shares of the company that issued the sukuk.

![]() Sukuk al-wakala is basically an agency arrangement in which the investors appoint an agent (wakeel) to make investment decisions on their behalf.

Sukuk al-wakala is basically an agency arrangement in which the investors appoint an agent (wakeel) to make investment decisions on their behalf.

![]() Sukuk bai al bithaman ajil is based on a deferred payment contract. The price of the asset is agreed upon by both parties based on cost plus profit, and the ownership of the asset remains with the financier. This structure is available in Malaysia, but not all sharia scholars accept it as compliant.

Sukuk bai al bithaman ajil is based on a deferred payment contract. The price of the asset is agreed upon by both parties based on cost plus profit, and the ownership of the asset remains with the financier. This structure is available in Malaysia, but not all sharia scholars accept it as compliant.

![]() Al istithmar sukuk (unlike most other sukuk) are based on intangible assets. Ijara contracts, receivables from istisna contracts, and receivables from murabaha contracts are packaged together and sold as investments. This structure, although not based on debt instruments, isn’t universally accepted among sharia scholars.

Al istithmar sukuk (unlike most other sukuk) are based on intangible assets. Ijara contracts, receivables from istisna contracts, and receivables from murabaha contracts are packaged together and sold as investments. This structure, although not based on debt instruments, isn’t universally accepted among sharia scholars.

![]() Green sukuk are another new and innovative type of sukuk based on sharia-compliant environmental credentials. Because Islamic investments are based on social responsibility, considering the environment as part of the investment process is a logical step. A green sukuk may be based on any of the Islamic contracts I discuss in this chapter.

Green sukuk are another new and innovative type of sukuk based on sharia-compliant environmental credentials. Because Islamic investments are based on social responsibility, considering the environment as part of the investment process is a logical step. A green sukuk may be based on any of the Islamic contracts I discuss in this chapter.

According to the International Energy Agency, approximately $10 trillion is needed to combat climate change worldwide. Green sukuk are one investment product being considered to fund initiatives that contribute to climate solutions. For example, in 2011, Dubai announced plans to issue green sukuk to finance solar parks (which are essentially energy plants that harvest solar power from photovoltaic installations), energy efficiency devices for homes, and biogas (biofuel) plants.

According to the International Energy Agency, approximately $10 trillion is needed to combat climate change worldwide. Green sukuk are one investment product being considered to fund initiatives that contribute to climate solutions. For example, in 2011, Dubai announced plans to issue green sukuk to finance solar parks (which are essentially energy plants that harvest solar power from photovoltaic installations), energy efficiency devices for homes, and biogas (biofuel) plants.

Charting the Growth of Sukuk

The sukuk market is one of the fastest developing sectors in the Islamic finance industry. As I explain in Chapter 11, the history of sukuk begins in 1983, when the first government-issued Islamic bond, the Government Investment Issue (GII), came from Malaysia. But GII couldn’t be traded in the market because it represented an outstanding debt, which isn’t allowed per sharia. So even though this product was pioneering, it lacked a crucial feature of sharia compliance.

As Chapter 11 also indicates, the Islamic bond market really began when sukuk were issued in Malaysia by Shell MDS for $30 million in 1990. Only a few sukuk were issued in the capital markets until 2001, when the government of Bahrain and Kumpulan Guthrie (a Malaysian-based company) issued ijara-based sukuk that seemed to kick-start the momentum of the sukuk market.

Since that time, the sukuk market has grown to include issues by countries such as Saudi Arabia, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Pakistan, Germany, Indonesia, Malaysia, the United States, the United Kingdom, Singapore, Brunei, Turkey, Japan, and Gambia. According to an International Islamic Financial Market report (see www.iifm.net), here are some examples of how sukuk products were represented during the period between 2001 and 2010:

![]() Malaysia issued 1,592 sukuk for a total value of $115 billion, which comprised more than 58 percent of the global sukuk market during that period.

Malaysia issued 1,592 sukuk for a total value of $115 billion, which comprised more than 58 percent of the global sukuk market during that period.

![]() Bahrain issued 125 sukuk worth more than $6 billion.

Bahrain issued 125 sukuk worth more than $6 billion.

![]() Indonesia issued 70 sukuk worth more than $4 billion.

Indonesia issued 70 sukuk worth more than $4 billion.

![]() United Arab Emirates issued 41 sukuk worth more than $3 billion.

United Arab Emirates issued 41 sukuk worth more than $3 billion.

![]() Saudi Arabia issued 22 sukuk worth $15 billion.

Saudi Arabia issued 22 sukuk worth $15 billion.

Sukuk issues suffered between the years 2007 and 2010 due to global credit crises. In 2007, $13.8 billion worth of sukuk were issued, but in 2010 new issues represented only $5.35 billion. However, as the financial markets strengthened in 2011, $8.5 billion in sukuk were issued: a 62-percent increase over the previous year. (The London Stock Exchange listed the largest number of sukuk of any exchange in 2011, with ten sukuk worth $1.5 billion.)

I fully expect the sukuk market to grow exponentially as many more countries join the market, new sukuk structures materialize, conventional bond issuers sell more sukuk, and non-Muslim countries issue and list more sukuk.

In practice, some sukuk are issued with repurchase guarantees just as conventional bonds are. Although not all sharia scholars agree that this arrangement complies with Islamic law, a product called

In practice, some sukuk are issued with repurchase guarantees just as conventional bonds are. Although not all sharia scholars agree that this arrangement complies with Islamic law, a product called