Week 7

Anticipate and Agenda Set

Have you ever been in a meeting with a client who seemed distracted? Perhaps you noticed her eyes wandering, or saw him reach for his smartphone. Or have you tried to get an appointment with an executive who just wouldn't make room in the schedule for you?

In both cases, the problem is the same. You're not compelling enough. You're not showing how you are relevant to the client's agenda of critical priorities.

How would you react if your plumber called you and suggested you get together for lunch so you could get to know each other better? How about if you got a call from your doctor, who asked you to come in to discuss your latest test results? Who would you make time for?

Clients are like the rest of us—they open their schedules for their most essential priorities.

If you want to be seen as integral to your clients’ growth and profitability, you have to demonstrate that what you do is strategic to their business. You must show that you are proactively focused on their most important goals. You need to demonstrate you can help them see around the corner and anticipate important, future influences on their business.

Do you really understand your client's agenda?

Every client has an agenda of three to five priorities or goals that they are focused on in their organization. It's rarely more than five, because after four or five they tail off in importance. And usually it's not fewer than three.

Client executives also typically have a set of three to five personal priorities. These are important to understand because if you aspire to build a trusted relationship with clients, you need to appreciate their total context. And there may very well be some personal interests or needs that you can help them with. One of my clients, for example, was interested in getting on a corporate board. I gave advice on this, and introduced the person to several top executive search firms that have specialty boardroom practices.

A professional priority might be to implement a new project management system, or to reduce costs. For senior business heads, it could be to expand into a new market, or make several strategic hires to augment their top team. Personal agenda items could include getting promoted, building a network, or helping their family adjust to living in a new city. It completely depends on the person and where he or she is in the organization.

I often am asked, “We are in a very competitive marketplace. How can we more effectively differentiate ourselves?” One of the best ways to do that is to learn more about your clients’ priorities, needs, and goals than any other competitor knows.

I had a client who was the top performing partner in his firm. Every year he consistently generated tens of millions of dollars in new revenue—mostly from his existing clients. One day I took him out to lunch and asked him about the secret to his success. He pulled a small square of wrinkled paper out of his suit pocket. “Andrew, do you see this sheet of paper? On it, I've printed the names of all my key executive clients. And next to each name I've noted their one or two most important goals for this year. My job is to help them successfully accomplish those goals.” He didn't define himself as a consultant who did strategy work or was an expert in re-engineering. Rather, his core mission was simply to help his clients accomplish their most important priorities.

How well do you know your clients?

By now, you may be thinking, “I know my clients pretty well. I'm doing ok at this agenda-setting thing.” But let me push back. I frequently ask large groups of very senior relationship managers and account executives—partners, managing directors, VPs, etc.—how well they understand their clients’ agendas. Here's the question: “For what percentage of your clients would you say you have a thorough understanding of their three to five most critical professional priorities? How about their personal agendas?”

For their largest clients—their key accounts—the answers are usually 50% (e.g., for half their clients they have a thorough understanding of the professional agenda) and 20% (personal agenda). On average, for all their clients, people usually say 20% and 10%. I call that flying blind. If you don't know your client's agenda, you are like an airplane pilot with no radar and no map.

What would these figures be for you and your clients?

The takeaway here is that many client-facing professionals actually have a poor understanding of their clients’ agenda. They may know what that agenda is in their specific sphere of expertise, but not the broader set of priorities I'm referring to here.

Three stages to agenda setting

There are three stages to becoming an agenda-setter. First, you react. A client calls you up and says, “We need help with this problem.” That's great when it happens, but if that's how you get all your business—waiting for the phone to ring—you're a reactive, expert-for-hire. Besides, by the time the client decides what they want to do, they may very well be talking to several of your competitors as well.

Second, you sense. Using various techniques, which I'll discuss shortly, you uncover the client's agenda. This is not as easy as it sounds. After all, are you willing to fully reveal yourself to someone you don't know very well or perhaps even just met?

It's often difficult to discern what your client's true agenda is. This is especially true as you go higher up in the organization. One of my clients, for example, a division CEO, had a four-part strategy he was very visibly following. But he had another very important agenda as well that involved building up his top team of direct reports. That wasn't in the annual report or his strategic plan. But after several in-depth conversations, this priority came to light. When I demonstrated I had experience and ideas that would help him in this area, he ultimately asked me to work with his executives and coach them.

Third, you anticipate. This is what separates the advisor from the expert-for-hire. As one executive told me, “My trusted advisor is always thinking two or three moves ahead. She is bringing me ideas and insights about trends, best practices, and competitive changes that may affect our business six, 12, or 18 months from now.” By anticipating, you become an agenda-setter. You understand, inform, and ultimately shape and influence your client's agenda.

This is a subtle process. It's rare that someone can walk into an organization from the outside and wow the leadership by revealing something of great importance that no one has thought of before. More likely, you slowly shape your client's perspectives.

One of my clients, for example, severely lagged in implementing industry specialization in their sales organization. Since their competitors were not very far along, either, they felt no need to change their plans. But their own industry was slow-moving and hardly a showcase for leading-edge management practices. Over a number of sessions I showed them how many leading companies in other markets were using an industry focus to drive substantial revenue growth. As a result, they dramatically accelerated efforts to organize around the key industries they served.

Anticipatory agenda setting can also be about implementation. A mid-sized client once retained me to help them implement a key account management program. We agreed on the goal, but I disagreed with many of my client's views on how to go about achieving it. For example, overnight, they wanted to designate several hundred clients as key accounts. I shared with them how some other clients of mine had done this, and the risks of starting with so many clients. Over the course of several discussions, I got them to agree to start with a pilot of just 20 accounts, to test and prove the concept.

I also helped them anticipate several problems they had not thought of. I warned them that relationship managers whose clients were not included in the program were going to feel excluded and even resentful. I then suggested several ways to mitigate this reaction. They also wanted to start with a 35-page account planning template. I told them that the emphasis had to be on creative, dynamic planning discussions, and that a shorter, five-page plan was not only sufficient but would get greater uptake from their people.

The key to sole-source business

Agenda setting is simple in concept but hard to execute well. First, you have to be a real student of both the external factors that may affect your client's business as well as internal organizational dynamics.

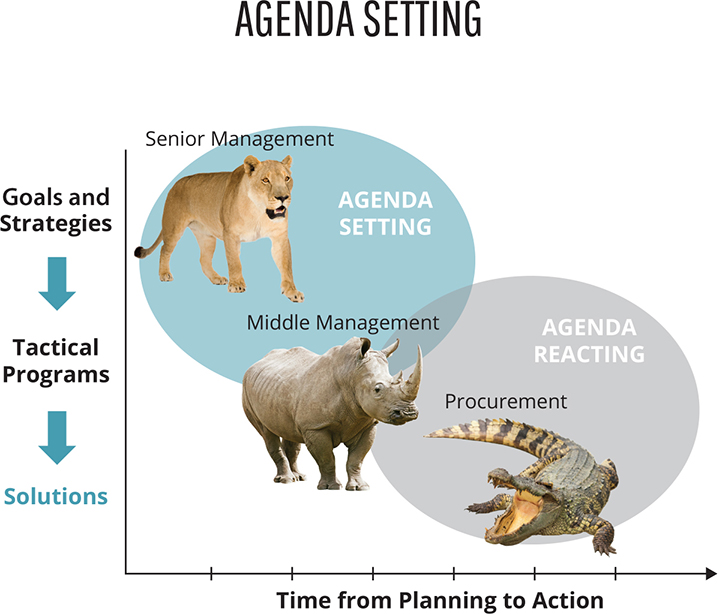

Second, you must penetrate more deeply into your client's forward planning cycle. Figure 7.1 illustrates this.

Figure 7.1 Agenda setting

If you wait to get calls from your client about a need they have already identified, you'll find yourself in the lower-right corner, where you are “agenda reacting.” Here, procurement—pictured as a hungry alligator—will be biting at your ankles. The client may very well be requesting proposals from multiple suppliers. There will also be much less opportunity to reframe the issue. At this point, the problem definition will be well established in the client's mind, and you'll have to take it or leave it.

Where I want you to be is in the upper-left corner. Here, you are discussing your client's future plans and priorities. You are bringing them value-added thought leadership in the form of insightful points of view, best practices, trends, and so on. By working together with the client to define the need, you'll have an excellent chance to win sole-source business.

Don't be a walking cliché

A senior executive I recently interviewed gave me an earful about how not to learn about her agenda. She told me: “I'm tired of hearing, ‘What keeps you up at night?’—which is just a lazy question. Another one is ‘What does success look like?’ Salespeople have been asking these for 30 years. I also get the ‘What are your top three priorities?’ approach. They take notes, and then say, ‘We can help you with number two.’ ”

You should come across as a potential business advisor who has a lot of wisdom to share, not a salesperson looking for a quick sale.

I find five different techniques very effective in sensing your client's agenda. First, despite my admonition in Week 3 not to over-prepare, you do need to prepare. As one executive told me, “You need to show up knowing the outlines of our strategy and what's important to us as an organization.” Remember—you just need a couple of hooks to engage your client. One of my clients was a master at this. He was an expert in executive compensation. He often found the clues to formulate penetrating questions in his prospective client's 10K report. He would tell a client something like, “I noticed that your treatment of deferred compensation is a little unusual.” Then he would go on to explain how most of his other clients did it, adding, “I'm curious, how did you make that decision?”

Lower the threshold for a client meeting

A well-known banker once said to me, “If I waited until I had a great idea to go see a client, I would only leave my office once a year.” His point was that you don't need a brilliant new idea or a finely tuned PowerPoint presentation to go and have a cup of coffee with a client and talk about how he or she is doing. Don't make it difficult to go see clients and prospects. Lower your threshold to have a brief meeting. The more clients you talk to, the more opportunities you'll have to uncover an important issue that someone is struggling with. And the more you'll learn about what's happening in your market.

The second approach, which you have to be cautious with, is direct questioning —e.g., “What are your top priorities for the business this year?” My experience is that the higher up you go, the less effective this question is. A top executive may not want to open up to you right away, and she may also expect you to already have a reasonable idea of what's going on in the company. Try this, but be aware it may not be the most fresh and engaging strategy. Sometimes, I make this more personal and ask, “Of the various initiatives you have going, which are you personally going to be highly involved with?”

A third approach is to ask implication questions. For example, I recently met with a prospective client whose new strategy was quite public. I was having a conversation with the chief learning officer (CLO). My opening questions were, “I'm familiar with your new strategy aimed at repositioning your firm in the large corporate segment. How is this impacting your priorities in learning and development? What new capabilities and skills do your people need to develop to facilitate this shift?” Similarly, you could ask implication questions about external trends or competitive changes. By posing these well-formulated but indirect questions, you establish your own credibility and begin to draw out the client's agenda.

A fourth strategy is to ask what I call emotional or personal questions, which I'll cover in more detail in Week 10. These questions get at your clients’ dreams and aspirations, as well as their fears and anxieties. The question, “As you look out two or three years, what are your aspirations for this business?” is more interesting than the dry and clichéd “What are your top three priorities?”

A final approach is to simply ask, “I'm curious, at the end of the year, how will your own performance be evaluated? What are the key objectives you've been asked to meet?” If necessary, I add, “I ask all my clients this question. I find that the more I know about my clients’ goals, the more helpful I can be.”

How agenda setting works

A client of mine wanted to build a relationship with a large retail bank. Through a contact who had worked at the bank, my client got an introduction to the head of the private banking division. They believed the bank was missing a major opportunity to cultivate younger professionals as clients. So they did a survey of their own Millennial employees, who matched this demographic, to better understand their attitudes toward savings and money management. When they met with the CEO of the private bank, they shared the results of their research, accompanied by some tentative recommendations about how the CEO could set about capturing this growing market segment. The CEO was blown away by my client's preparation and insights. They procured a major, sole-source engagement to help develop and implement a new “young professionals” strategy for the bank.

While this type of agenda setting may seem outside your reach, it does illustrate the power of anticipating your clients’ needs. There are many smaller but nonetheless impactful things you can do to agenda set with your clients.

Four agenda-setting strategies

The very first thing I recommend is to schedule a regular agenda-setting conversation with all of your established clients. Position it like this: “With our best clients, we meet periodically to step back from our day-to-day work together and talk about the big picture surrounding the engagement. It's a chance for us to share our latest thinking, talk about best practices from other client engagements we're involved with, and give you our observations about improvement opportunities within your organization. It's also a chance for you to share with us your evolving plans and priorities and any corporate initiatives that may impact our work.”

A second agenda-setting strategy is to regularly share points of view about your clients’ business, their challenges, key trends, and so on. This could be as simple as talking about how some of your other clients are tackling the same issues.

A third and very effective strategy is what I call the “deep dive.” Offer to facilitate a working session on an important issue your client is facing. This could be over lunch, or even a half-day workshop. If you work with a large firm, bring other expert colleagues along. One top executive I interviewed referred to this as “the ticket to entry” for a major provider they worked with. He explained: “One year, we were very focused on asset utilization across the company. This firm put on a one-day workshop on strategies to increase asset productivity. They brought a bunch of their experts, and we fielded a team of our people who were involved in various internal initiatives in this area.” The result? The firm rapidly became this company's provider of choice in their area of expertise.

Finally, if you work with a large firm, systematically gather intel from other colleagues and team members who are working on the client account. What are they seeing and hearing? During a panel discussion that I moderated, a client executive highlighted the value of this: “You are a major supplier to my company,” he told the audience. “You know as much or more about our operations than most of the outside providers we work with. Tell me what you're learning. Give me ideas about how to improve our business.”

Ignore the barriers

Many factors will conspire to keep you from agenda setting with clients. Don't let them! You'll find that most of your client conversations are about operational execution and product and service delivery, and it's hard to carve out the time to take the big-picture view that agenda setting demands. In some cases you'll feel that your client is too junior to practice agenda setting with. Other times, you'll get cold feet because you think you won't be able to carry on that higher-level discussion about the client's business. Most of these barriers are manageable. Break through them—you owe it to your client to excel at anticipatory agenda setting.

PUTTING KEY IDEAS INTO ACTION

- Select your three most important clients. How well do you understand the professional and personal agendas of your key contacts? What can you do to fill in your knowledge gaps?

- Think about an upcoming client meeting. How could you turn it into more of an agenda-setting conversation? Specifically:

- How can you engender a deeper discussion about your client's future plans and priorities than would be typical for an operational update?

- What new ideas or perspectives can you introduce in the meeting?

- What questions can you ask to learn more about your client's agenda?

- How can you more directly tie your work to the client's most important strategic or operational goals?

Additional Free Resources for You

Download my free Client Growth Guide at www.andrewsobel.com/growth-guide. It includes two worksheets to help you with Agenda Setting: How Well Do You Really Know Your Client and How Well Do You Really Know Your Client's Organization.