Chapter 8

Capture the Action

If chess has any relationship to film-making, it would be in the way it helps you develop patience and discipline in choosing between alternatives at a time when an impulsive decision seems very attractive.

Stanley Kubrick

8.1 INTRODUCTION TO REALITY

Reality is the latest incarnation of non-fiction television. It is a genre that covers a wide variety of diverse programming. The unifying element is that all of these shows feature real people being themselves, hence the term reality. Even if the stars of a reality show are celebrities they are shown as themselves and not playing a character. In order to make programming that is entertaining and that uses regular people who are not professional actors or performers, the reality world is built on casting, producing and editing.

For decades, the American public watched hidden camera shows, game shows, nature films and documentary series like An American Family: The Louds (Pat Cook, Eleanor Hamerow, David Hanser, Ken Werner— editors). This groundbreaking series aired in 1971 and was originally intended as a chronicle of the daily life of the Louds, an upper middle class family in Santa Barbara, California. It ended up documenting the break-up of the family and subsequent divorce of the parents Bill and Pat Loud. Many consider this series to be the first reality show.

The popularity of reality programming as a genre began in the early 1990s with the breakout success of The Real World and has since mushroomed into countless iterations based on a similar premise. Docu-series are a series of shows that are close to actual documentaries and show us true stories and real people. Parts Unknown is a widely popular series featuring the world-renowned chef Anthony Bourdain as he travels across the globe to uncover little-known destinations and diverse cultures. Producers heighten the tensions in docu-dramas by creating more interest in real people or in a real situation. The Deadliest Catch is a series that chronicles the real-life high-sea adventures of the Alaskan crab fishermen reputedly the most deadly profession in the world. Docu-follows are more of a slice of life or a character-driven piece instead of over-the-top drama. The Simple Life featured wealthy socialites Paris Hilton and Nicole Richie and follows them as they struggle to do manual, low paying jobs such as cleaning rooms, farm work, serving meals in fast-food restaurants and working as camp counselors. Docu-soaps sometimes have soft-scripted story lines and the cast may receive direction or coaching from the producers to enhance the drama. Starting Over was a docu-soap that ambitiously aired an episode every day. It followed the stories of women who are experiencing difficulties in their lives and want to make changes with the help of life coaches. There are also reality competition shows where real people are put into produced but unscripted situations. Here real people must learn to adapt to an unusual situation and to each other. Billionaire: Branson’s Quest for the Best had contestants working alongside Branson for three months to win a million dollars. Some people also include the major singing or dancing competition shows as part of the reality genre. The Voice, Dancing with the Stars and American Idol are currently the most popular in this category.

The appeal of reality television is rooted in the real thoughts, experiences and emotions of the cast. Reality characters are not trained performers; the personalities they project are their own and their conversations are unfiltered. Casting is critically important. The success of a reality show depends on having characters that pop. That is why so many reality characters are seen as extreme in some way. They may appear raw, clueless, politically incorrect or sweet, funny, overly emotional or somewhat crazy. Their aberrant behavior becomes fascinating to watch. Truth is often stranger and more intriguing than fiction.

Reality television does not always present action captured in real time. Some shows feature recreations of events that happened in the past or off-camera, and some may be largely soft-scripted or produced. Sometimes cast members are given tasks to perform or challenges to complete and sometimes they are given pre-planned storylines to follow that are consistent with their character.

Depending on the show, there may also be pick-up interviews shot after the main reality has been captured. This covers new plot developments or provides clarity about what has already occurred. In many ways these shows do not truly reflect reality. They are designed to entertain and keep audiences watching. There can be no boring moments in these stories. As reality programming garnered greater viewership and commercial potentials increased, producers began to raise the ante. Celebrities unabashedly flaunted their vulnerabilities and the world gravitated to watching their relationships playing out in their living rooms. There is a growing resistance to the term ‘reality’ for those who work in this genre primarily due to its association with programs such as Keeping Up with the Kardashians. Many prefer the term ‘unscripted.’

Alongside the commercial proliferation of sensational shows there are still serious filmmakers who continue to use the reality format as a means of discussing social issues and exposing topics of deep concern. Hoping for positive outcomes, they offer resolutions and present hope and redemption for the characters involved. Many reality programs choose to tell relevant stories that will make a difference in society as in Beyond Scared Straight.

Whether you work on a show like Dancing with the Stars or Survivor, you will find the editing approach and the experience totally different. Every show creates its own style and format that will best tell its story and entertain the audience. Workflows and editing responsibilities are different on every show. The amount of editors and the sharing of media and cuts on the acts and the whole show differ from production to production. There are no two venues that are organized the same way. More than in any editing venue, whether fiction or non-fiction, you will have to learn to be a consummate team player.

Like many documentaries, reality shows mix shot footage, generally referred to as the reality, with sound bites from the cast. These can be proper sit-down interviews, or short check-ins shot on-the-fly or in-the-moment during the action or on location. Some shows use confessionals where the cast members are given small handheld cameras and reveal their thoughts and feelings in self-shot video diaries. There are also some reality shows that use no bites at all and tell their stories through reality footage only.

Each reality show will have its own style, tone, manner of storytelling and workflow. There are two challenges that they all present. The first is to figure out how to tell the best story possible with the reality, interviews, music, B-roll and coverage you are given. The second challenge is to get through a very large amount of footage in a never-enough amount of time to be able to hit the airdate. There is no one way of cutting a reality show. There are guidelines that can be adapted in each and every situation. The overriding commonality though is that each editor on the show is a pivotal storyteller who weaves all the elements together in the segments assigned to him. This storytelling talent is again the greatest strength you can bring to the table.

8.2 FIND THE STORY

Reality programming is not scripted. The story unfolds as it is happening on location or in a studio. Many cameras cover the action and events. The shooting ratios are high and coverage can exceed ratios of 400:1. There are many elements that go into creating the shows. There are often background packages of the characters, on-camera interviews, confessionals, B-roll, music, graphics and a variety of filmic elements necessary to create an entertaining story. Organizing all the material is key. Every post facility is a problem-solving environment. It is the responsibility of the assistants to organize the massive amount of material on the server. Today, with sophisticated media-share technology, everyone in post production is able to work on the same material at once and share cuts, footage, B-roll, SFX and MX and have access to all the files at the same time. Finding the story for the program is the challenge.

• Once all the footage is digitized and grouped, a story editor, also called a story producer, will review the media, select bites and footage and put together a paper cut that will be strung out by an assistant editor. This stringout is assembled on a timeline and constitutes a rough story outline for the editor to use as a basis for the cut.

• Some shows, generally the larger shows, do not use stringouts and schedule time into their post production schedules for the editors to watch all their footage and pull their own selects. Many editors like to view all the reality so they can familiarize themselves with other story options and choices.

• If you are an editor on a show that employs stringouts, you will soon learn to gauge if the stringout you have been given is workable or whether you need to go back into the footage and watch the raw footage for preferable selects.

• Cutting will begin from either the prepared stringout or from the editor’s own selects.

• Every editor and every company has a unique way of working and the function of the story producer differs vastly from show to show.

• Many productions have multiple story editors and multiple editors working on one episode.

Marlise Malkames ACE (The Bachelor franchise, The Hills, The Apprentice) cuts reality episodes with several editors working on the same show. They have organized a method of finding the story that is unique to their situation.

At The Bachelor, we do not use stringouts. When I start to cut a new episode, everybody who is working on that show will get together and have a story meeting to discuss the story arcs, the main characters, the big beats, and we all agree on a structure. Then, as we are putting the show together, we may need the story producer to pull bites for us. They will go through the interviews and will find all the bites where one cast member talks badly about another or where people talk about a specific event. I like to pull my own material because it gives me more ideas for cutting.

Marlise Malkames

Stringouts so often depend on the abilities of the story producers and their gifts for storytelling.

Stringouts are a nice starting point if you have somebody who really is good and understands story. Story producers I find are a lot like assistant editors. A good one makes your world perfect, a bad one makes your life a nightmare. I have worked on shows before where I have relied heavily on story producers. I have worked on shows where I have thrown out their stringouts and said, “Thank you very much for that. Now I’m going to go back in and craft it myself.” I have always subscribed to the notion that whatever a story producer gives you, look thirty seconds before and thirty seconds after because that is where the real gold is going to be.

Mark Andrew

But for some editors, like Sharon Rennert ACE (The Bachelor, The Real World, High School Reunion), the story editor plays a vital role.

The good story editors can be invaluable. When we are under the gun and we need to rethink the overall stories that we are telling, it is really helpful to have a great story editor around who can offer suggestions. They know all the footage and they understand the storytelling. When you are looking to locate a crucial line or piece of action that will pull the story together, they can be invaluable in helping you find the missing links. If an editor is under pressure and has to meet a deadline and has to work with someone who wants to help but does not get it, it can be a hindrance.

Sharon Rennert

Finding the best story hidden in the hours and hours of reality is the biggest challenge facing the editor. There are so many variables and factors that can influence the direction, style, tone and intent of the piece. Not least is the fact that your show might be a stand-alone episode in a series or one episode of an ongoing series. This again influences the role of the story producer in helping focus the story.

On The Bachelor where you have a ten-episode arc with the same characters, the story producers become a lot more essential, because they’re the ones who are really going to be able to tell exactly how episode 3 is going to affect episode 5, which is going to affect episode 7. These decisions are actually created by the producers and passed on down to the story editors. With a self-contained story on each episode, the editors need the story producers a lot less. On Beyond Scared Straight which is a self-contained episode where every character only appears in that show, we do not work with story editors or their stringouts for the main story. We look at every frame of footage and cut all of the reality.

Mark Andrew

You can manipulate and shape the story and characters in so many directions. Remember, you are not alone as the creator on the show. With a guide from the story producer, there are always notes from various producers and the network that have to be acknowledged and incorporated into the cut.

Reality is a different animal than scripted episodic because in episodic, your script is pretty much the story that’s going to air whereas in reality there are many variables. The story that actually makes it on air is dependent on what happens at the end of the show and how the characters resolve situations, on what happens in the field, on what the producers want, on what the network is looking for, on how the viewing audience responded to what has happened on previous seasons, on how your lead looks or how a character acts. Are they too harsh? Are they not harsh enough? Is this romantic? Is this not romantic enough? Is the action clear and does it make sense or do we need to tell the story a different way? You may go into a screening with an executive producer having given it your best shot at cutting the footage as it was produced, but by the time you are screening in post they may have something completely different in mind. Maybe something happened in the field, or maybe the season ended differently than everyone expected. Perhaps the network has new thoughts. Scenes you originally thought were important are often discarded and footage can be repurposed and recut in a completely new direction. It is really an editor’s medium.

Marlise Malkames

The challenges of cutting reality can be overwhelming with issues you have no control over. The story editor has a great perspective on the overall series story arc and could provide invaluable information to the editor about future episodes and where the story needs to go and how the characters develop or how and when they leave the story. Seek their participation when necessary and work their suggestions into your cut. Learn to be part of a team.

8.3 WORK AS A TEAM

If you work as an editor in reality, you will work as a team member with many players sharing a show.

• Every production company will organize the setup of the editing teams and their responsibilities according to the demands of the show. Post producers have to factor in the deadlines, the amount of coverage, turnaround of cuts, screenings or the number of assistants. These are some of the issues that influence how the workflow is divided between the various editors.

• Working as a team member in a multi-editor situation requires a whole different set of skills to working on your own as editor on a show. Good attitude is vital. Cooperation is key. It is common to find one editor recutting the work of another and it is imperative that the editor accepts this graciously.

• Most shows have different levels of editors working together to get the episodes cut and on air. A lead editor goes by many different names including showbuilder, finisher, supervising editor, sometimes even co-producer. His responsibilities vary from show to show, but in general he is responsible for ensuring uniformity of the series’ style, getting the show to time and making sure that all executive producer and network notes are addressed successfully. This includes recutting scenes or sometimes entire acts at the last hour. He checks the graphic elements, the transitions and formats every episode ready to air. With so many editors cutting segments, he ensures that each episode is consistent in style and format. There is also an unofficial term for a lead editor who post produces his own work; he may be referred to as a preditor.

• In addition to lead editors, there are act-cutting editors who do the first or sometimes second pass on an act before handing it to the showbuilders.

• There are tease editors who are responsible only for cutting the teases for the episodes.

• Sometimes there are specialty editors who cut specific set pieces which could be challenges, boardrooms, live performances, competitions and other sequences specific to the show.

• At all levels, editors are expected to cut in all MX and SFX as well as the reality and all sound bites.

Part of working as a team means that somewhere along the line your work might be recut, shortened or changed before the show is locked.

The showbuilders—and there could be two or three per episode—will take over the show and finish the work. If we are designated showbuilders, we will recut or finish all our team’s work as well as our own. You need to work as a team because sometimes you get hammered with notes and you have to hit air. Recently I had a big chunk of a show still to cut so they brought in another showbuilder who had less to do and he took over some of my stuff. Would I have loved to do it myself? Sure, but it’s going to be a great show and the guy’s a terrific editor as well and we’re all friends who have worked together for a long time. You develop a collaborative attitude. It’s not always the happiest thing to not be able to finish all of your own work but we all need help sometimes. Getting it on air is the most important thing.

Marlise Malkames

Editors share a common loyalty to each other. A successful collaboration between editors is vital to the success of the cut. Camaraderie and trust should ensure that no editor talks disparagingly about another when there is a producer or director in the room. Personality often plays an important role and egos need to be sublimated. It is all about working together to create the best show possible. No matter the size of your team, it is teamwork that will give these shows coherence, uniformity and unity of vision.

On The Bachelor when we’re in full tilt in the middle of the season we have about twenty-six editors and seven or eight assists, some working day and some working at night and we cut in teams. The teams are assigned based on what is needed for each episode and every episode has a different combination of editors on it. We are assigned according to our ability and expertise. Editors with less experience cut easier segments while the more experienced editors cut the special acts when something unexpected has happened. On The Apprentice and Survivor, there are four four-person teams that move through the season as a unit doing every fourth show together. The lead editor is the showbuilder, the second editor cuts the scenes of the losing team, the third editor cuts the winning team, and the fourth cuts the setup moments and whatever else is needed. Speciality editors cut certain challenges. On some shows everyone cuts and finishes their own episodes and on other shows all episodes must pass through a single finisher. There are dozens of different workflows in reality.

Marlise Malkames

Cooperation is essential as a team member. There should be no hard feelings having someone recut your scene. Understand that it was done to improve or shorten the cut. Vince Anido ACE (The Millionaire Matchmaker, Secret Millionaire, Celebrity Wife Swap) understands the challenges of working as a team member.

You get used to this kind the process and working as a team. Sometimes the person who has the first crack on the scene will kill it and you won’t ever revisit or touch it again, but then there’s always those scenes where the whole episode hinges on it. Often those get reworked in five or more different ways till it is right. “Sorry it is your turn this week. You get to deal with that.” It is just part of the process and some people take it better than others. If you’re one of those people who are having your stuff recut, look at it and say, “OK what did they do differently?” This is a great learning experience especially when you’re a junior editor. You have to learn to dissect that and then you grow and learn.

Vince Anido

Respect the ethics and the integrity of the editing room. Remember what happens in the cutting room stays in the cutting room. This is a safe, secure place where people are free to express their ideas without negative consequences. On the whole, keep your personal feelings and opinions to yourself. At all times be professional. Do your best work, develop a pleasant attitude and be respectful of everyone and everything. Adhering to these principles may ensure that you will be invited back.

We always try and share duties in the most respectful way possible. If anyone on my team sees something in the work and they have comments or notes, we discuss it privately within our small group. It’s not brought up when we go into a larger screening where the supervising producers, the executive producers or the network are present. We represent a unified team when we present our cut. We support each other when the executives question something about the cut, even if we questioned the same thing in private.

Mark Andrew

Because you are part of a team, it is very important that there is conformity of timeline management in reality editing. Since your work is very likely to be recut by a finishing editor or someone else on the team, it becomes vital to use the same parameters and track assignments to make the workflow smooth and enable the next editor to do his work quickly and efficiently. These parameters are usually set by the supervising editor and are a part of a style guide for the show.

• An often-used format is to keep production sound on track 1 and 2, interview bites on 3 and 4, SFX and VO on 5 and 6, and MX on 7, 8, 9 and 10. More tracks can be added for SFX and MX as needed.

• Make sure that your track splits match the other cuts.

As editors you are always learning how to craft the best show you possibly can. There are so many choices and decisions about what material to include and what to exclude that it can be overwhelming. If you are stuck ask a co-editor for an opinion. Someone else might just have a fresh approach to something that you have agonized over. Revisit your cut after the re-edit. It will open another door to understanding how to handle problematic material and turn it into gold. Treat it as a learning experience from which you can expand your talents and grow. In the world of episodic dramatic television, if the editor’s work is recut by another editor it is an ominous sign that you might be replaced soon. In reality shows, it is par for the course. Trust, cooperation and loyalty to each member of the team are of the utmost importance.

8.4 STACKING AND AUDIO TRACKS

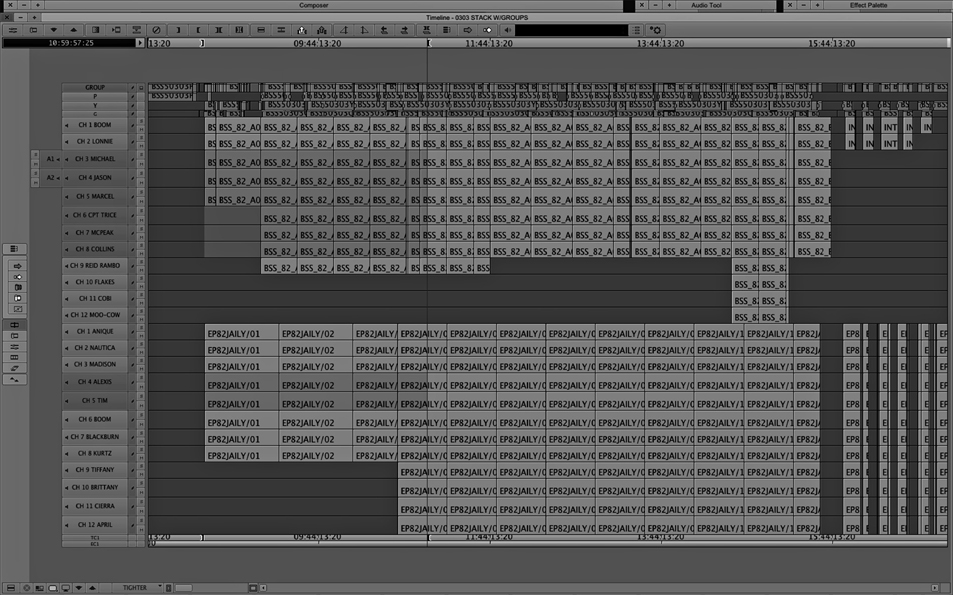

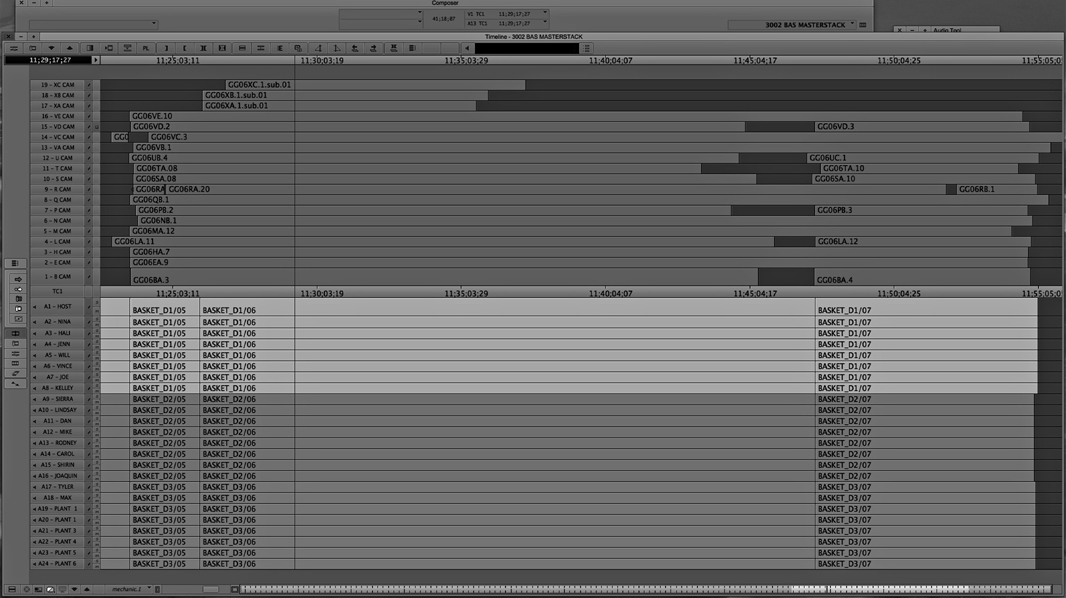

In reality productions it is common practice to capture the action using multiple cameras. Many innovative angles captured from unseen cameras placed in hidden and strategic corners of the set allows for greater coverage. This in turn presents challenges for the editor as he wades through hours of footage trying to craft a show from the multiple editing choices at his disposal. All the media has to be organized by the assistant editors in a way that can be efficiently managed by both the editors and the story producers. One of the best methods of arranging the media is to create a stack of all the footage on the timeline.

• The assistant editor assembles each camera on different visual and audio tracks in the same timeline all synced to the same matching time code. In this way you will have matching action from different cameras stacked one on top of the other. This immediately facilitates the viewing of the dailies and the coverage at any point of the shoot during the day. When each camera turned on and off is represented on this timeline.

• The different cameras do not always cover all the action at the same time so you might find that one camera did not capture the action from a certain point but will pick up capturing at a later time code. On the timeline there will be a gap for this camera, which will sync up once that camera starts rolling again. In this way it is possible to see where there is coverage for the sequence from all the different cameras at the same time or coverage from maybe only one camera at any particular point in time.

It is arduous to create the stacks but it is invaluable for the editor. Toggling between the different tracks will give immediate access to all the coverage available. He can review all the material with great speed. The editors do not cut with stacks. They cut with multigroups prepared by the assistants. The stacks are only used by editors as a reference for coverage. On scripted dramatic shows the editor receives detailed coverage notes from the script supervisor with a description of every shot and pickups clearly numbered. Even the director’s choices of the best takes are circled for the editor. All this information is notated on a corresponding facing page. The reality editor will normally only receive minimal field notes from the location. The stacked timeline becomes the visible indicator of the coverage for the scene.

It is best to think of the stack as a painter’s palette. I can look at this palette, this timeline, and I can see every bit of footage that was shot on that day. It shows me every camera, every piece of audio. After the assistants create the stack they have to take all of the video and group it, so that we will be able to do a live switch as we do with ordinary grouped footage.

Mark Andrew

In addition to the multi-cam setup used for this style of coverage, there are also many audio tracks that are recorded on set.

• The primary soundtrack for the show is recorded on a boom and syncs with the main camera. In many cases all the actors or participants each have a separate Lavalier radio microphone which records their audio on a multi-track recorder. All these tracks are delivered on a hard drive so the editors have the ability to pull the best sound from each person.

• Typically the editor will get a live mix on tracks 1 and 2 which is what the sound man in the field thought was the best audio at the time. Often a character may be off the main camera microphone but because he is wearing a Lavalier radio microphone, his sound will be clean on the multi-track recording. If the editor wants to look for better sound quality he goes back to the original 16 or 24 tracks of the multi-track recorder. This enables him to find a better take and improve the quality of the sound track.

• If all the tracks are not usable, there is always an option to subtitle the inaudible or muffled line or to ADR it.

FIGURE 8.1 Example of a stack from Beyond Scared Straight. It is a full day stack with three cameras and the grouped footage on the top layer, with audio tracks from two different sources synced below.

FIGURE 8.2 Example of a stack for an immunity challenge from Survivor. It has far more cameras and most run for the entire challenge and there are therefore, fewer gaps.

It can be quite tedious listening to all the tracks that were recorded at any one time but sometimes something magical emerges. You come across other interesting bites that could be vital to the cut. In reality editing you are always looking for something special, some little kernel that will enhance your story or add a special note about a character or a story point. These are nuggets of gold.

With the tapeless media of today the problem intensifies because there are many small cameras like the Pilko Cans and the GoPros and even flip-phones. These little semipro cameras are used to create exciting POVs or are mounted onto objects that go places where larger cameras cannot navigate. Even drones have cameras mounted on them to capture unusual aerials of a location. This factors into the footage received in the edit bay. Because of conditions at the location they might not have any time codes. They will probably not be stacked. You have to figure out where they fit and how best they can be utilized to add color and drama to your story.

A good guide to remember is to go with the flow. If things are not always to your liking, do not voice criticisms of the crew or producer. That is not your job. You are there to make the best film you possibly can with the footage and audio available. Use your stack and group clips to foresee potential problem areas where there might not be enough coverage. Be creative in finding editing solutions.

8.5 APPROACHES TO CUTTING

As the editor you are generally autonomous in looking for the story points, developing and defining the characters and enhancing the drama in each situation. You mold the story. It will be shaped by your choices and tastes. Tackling the material and deciding how to approach the narrative and finding the elements with which to work is different in every situation. Starting points will depend on the nature of the film and material you have been given.

When I walk in on the first day I am given a casting sheet, which lets me know who the characters are. Then I will watch the footage, every bit of it. As I am going through the original footage I throw markers on it and say, “This is a good confrontation. This is something that could be funny. This is an interesting reaction. This could work as a transition.” I just ignore the things that do not impress me. It is more about being selective of which moments will tell the story in the best, most understandable light.

Mark Andrew

On our show there is no script and there is no outline. You are just given the material you have to cut. Our schedules are pretty tight, but I look at all the material and pick selects. If I am doing an act, I will pick selects for a specific beat. Then I go on and create sequences of selects. I look at everything so that I always have that as a reference and because we might be questioned on it at screenings, I always know where everything is. The most important thing is to see everything and then work with that.

Sharon Rennert

In reality as with documentary, it is advisable to view all the material before making your first cut.

• If you are not working with a given stringout, watch all the footage and mark selects and create subclips of story beats.

• Assemble all the clips into a potential story line with all the beats from which you can create your cut.

• Find the dramatic moments, the moments of conflict, action that propels the story and defines the personality and make sure to include them all. From this lengthy stringout you will be able to mold your story.

• Go through all the interviews and pull important bites from each character. Bites that you feel will reveal the character, reflect their conflict and that will emotionally enrich the story. Find those moments that will propel the story and heighten the drama.

• View all the B-roll and be familiar with the footage so you can draw on establishing and beauty shots and material that will add color and texture to the story.

• If you are following a stringout, work through the timeline and embellish the tracks, both visual and aural, as you work through the story.

• Use the group clips or the stack to find additional coverage of parts of scenes that need building.

• If your show has confessionals, include them where applicable. They can be integral to linking dramatic situations and propelling the narrative.

• Work with MX as you cut to help create the mood or tension and punctuate the essential moments.

• Enhance the tracks with appropriate SFX.

• Follow any and all guidelines. Make sure you are editing in line with the established mood, style and tone of the show.

• Check that you include the correct graphics and transitions.

• Include titles and chyrons when you make your first cut.

• You will always be working tight deadlines and, at the beginning, will certainly be putting in extra hours, possibly unpaid. As you gain experience and master the craft, you will learn to work speedily and meet the deadlines with more ease.

• Do not rely on editing help from your assistants. They are overburdened with their own responsibilities. They have so many duties, from ensuring that the machines are all running to prepping outputs, that they do not have time to help you as they would on scripted shows. They are not available to add your SFX or to lay in your MX. Sometimes there are emergencies and it might be necessary to ask the assistant to help find a bite, some MX or a SFX. But do not rely on them to be there to help you complete your cut.

When you are working on large shows with many editors, you will probably just be responsible for cutting the segments and handing them over to the lead editor who will finish the show and take it to completion. The assistants and producers will ultimately be responsible for the overseeing the technicalities of getting the show to online and beyond.

8.6 CONCLUSION

There is no single way to cut a non-fiction film. There are umpteen guidelines but there really are no hard-and-fast rules that are set in stone. Every film is different, a unique world unto itself. Each show breathes its own life. A camera following a down-and-out musician desperately trying to reinvent himself going from one squalid dive to another is totally different to following a herd of elephants across the plains of Tanzania as they are pursued by poachers tracking them for their ivory. Exploring a subterranean world of unmapped caverns in New Mexico will require very different storytelling techniques to a documentary about young girls trying to defy religious extremists and attempting to get an education in the Sudan. Often there is no way to foresee what the camera will find. It is only in the editing process that the story will fully unravel and reveal itself. It is up to you, the editor, to expose its heart and soul and make it accessible and understandable to all who view it. But remember, moviemaking is a collaborative process. And no matter what film you work on, it is not yours. Never for one moment forget that you have to remain true to the intention of the director.

Editing documentaries and reality is excessively labor-intensive. It requires complete, unfettered dedication to the art and craft of the medium. Whether you have years of experience cutting fiction or non-fiction or if you are just starting out on your editing career, it is your personality, your experiences, your attitude and your perception of life that will influence and shape the work. Nurture an insatiable sense of enquiry. Stay current on world affairs. The non-fiction world embraces everything that makes the universe tick. Whether you are examining wriggling amoeba on a slide under a microscope or trying to make sense of an exploding star in a galaxy far, far away your instincts, your experience, the sum total of your knowledge will contribute to how the final product turns out.

Follow the guidelines, abide by all the rules passed down to you by your mentors and your peers and then know how, when and to what extent you can bend them. Every film is a learning experience. As long as you sit in a dark room manipulating images and sounds you will never stop learning. Every film you lay your hands on will improve your skills and enrich your life.