1

The Quick Trip: Eighty Percent of Shopper Time Is Wasted

“I am the world’s worst salesman; therefore I must make it easy for people to buy.”

In the fall of 2008, Wal-Mart launched a set of small stores in Phoenix, Arizona.1 With the arrival of these “Marketside” stores, it was clear that even the king of the mega-store was beginning to think small. The move was apparently in response to the arrival of UK retailer Tesco, which had come to the United States with its “Fresh & Easy” small-format stores. Tesco opened dozens of the stores in Nevada, Arizona, and Southern California. Safeway, Jewel-Osco, and many others are downsizing stores in an attempt to upsize profits. Retailers such as Trader Joe’s and other specialty stores have also successfully pursued the smaller store model in the age of mega-stores. When Wal-Mart is building smaller stores, it is clear that there is a shift in the winds. At the heart of this change, and the success of these smaller formats, is the quick-trip shopper.

Across the pond, German discounters Lidl and Aldi are growing rapidly in the British market with stores that are a tenth the size of Tesco or Asda stores. The smaller stores offer a faster trip with a more limited selection at lower prices. Although large UK superstores typically stock 32,000 different items, so shoppers are likely to find any obscure product they need to stock their pantries, Lidl carries 1,600 SKUs and an Aldi store sells just 900 items.2 Aldi, which arrived in the United States in 1976, has more than 1,000 stores. It is rapidly expanding its U.S. presence and competing aggressively against Wal-Mart and Kroger’s, using a limited selection and lower prices, as well as very different store designs.3

The rapid growth of Lidl and Aldi was aided by a tough economy in 2008, which sent more shoppers looking for discounts. But their success also depends upon an understanding of the power of the quick trip. Most supermarkets are designed for shoppers who are stocking up their pantries, but most shoppers walk out of the store with only a few items. In fact, the most common number of items purchased in a supermarket is one!

Three Shoppers: Quick Trip, Fill-In, and Stock-Up

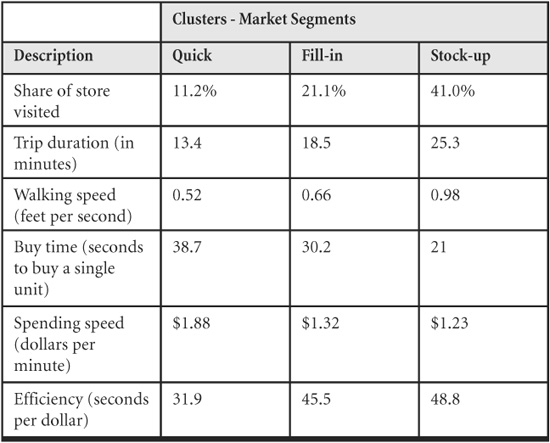

Building on the work of Wharton Professor Peter Fader, we studied data collected on 75,000 shoppers across a series of three stores to develop behavioral segmentation of shoppers. By mathematically clustering a large number of shoppers by factors such as how fast they walk, how fast they spend money, how much of the store they visit, and how long their trips are, we found that shoppers group themselves into three basic segments or clusters, as shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Quick-trip shoppers spend more quickly than other segments.4

Each of the segments exhibits fairly distinctive shopping behavior, as follows:

• Quick: Short time, small area, slow walk, high-spending speed, very efficient.

• Fill-in: Medium time, medium area, slow walk, average-spending speed, modest efficiency.

• Stock-up: Long time, large area, fast walk, low-spending speed, lowest efficiency.

Very few supermarket retailers are aware that half of all shopping trips result in the purchase of five or fewer items (these numbers come from actual transaction logs from every continent except Africa and Antarctica). This ignorance is a consequence of the justified focus on the economics of the stock-up shopper, and a lack of attention to the behavior of the mass of individual shoppers in the store. This huge cohort of quick trippers is not a different breed of shoppers. They are simply stock-up shoppers on a different mission.

Anyway you slice it, these quick trips are an important part of retailing. Single item purchases account for more than 16 percent of all shopping trips. Further, as noted, half of all shoppers walk out with five items or less, and the average purchase size is about 12 items. As shown in the figure, in addition to looking at the average, we also need to consider the “median,” half of the distribution, and the “mode,” the most common result (see the box for discussion).

But it is not sufficient simply to begin catering to quick trippers. Rather, the store must be distinctly managed for all three types of shoppers, particularly the quick trippers and stock-up shoppers. Supermarketers are obsessed with stock-up trips, because even though there are so few of them, each one is worth a lot of money. But this has led to ignoring the importance of the one- to five-item trip. Even though these are smaller baskets, there are so many of them that they still constitute fully one-third of all the store’s sales. What is more, they represent a tremendous opportunity. Although it might be hard to convince a stock-up shopper to put another half-dozen items into a bulging cart, the quick tripper may have a hand free or room in a basket if the right product comes into view. Because the one- to five-item basket is presently generating one-third of dollar sales, simply doubling the size of those small baskets would increase total store sales by more than 30 percent.

But this is not simply about figuring out how to coax customers into picking up a few extra items on trips that continue to look just like the ones they are taking now. Instead, there is a need to understand distinctly the three primary types of shopping trips: quick trips, fill-in trips, and stock-up shopping. Those retailers and brands that make a conscious and focused distinction between the quick trip and the stock-up trip will steadily pull ahead in sales and profits.

Rise of the Small Store

When supermarkets failed to respond to the needs of half their shopping trips, others stepped into the vacuum. This led to the creation of the entire convenience store industry and encouraged the growth of competitors with small-store formats. In 2007, for the first time in two decades of expanding superstores, the average size of a grocery store fell slightly. It appears that large retailers are finally waking up to the power of the quick trip.

Many of these smaller stores such as Lidl and Aldi attribute their success to their low pricing. But in addition to offering discounts, they have created streamlined stores that reduce navigational and choice angst. Many consumer studies show that pricing is not the primary factor that drives retail. Giving people money to buy things has to be the least creative way of selling something. As with Stew Leonard attributing his success to superior customer service, the success of retailers might not be for the reason they think. In the case of Lidl, Aldi, and others, our studies indicate that the reduction in SKUs and simpler navigation may play as great a role as pricing in their success.

At the same time that supermarkets were being attacked by the small stores from below, the big box outlets were taking a large slice of the stock-up shoppers. Winning retailers of the future will earn their top-tier status through clearly distinguishing shoppers into quick/fill-in versus stock-up, and serving the two groups distinctly, rather than dumping the whole store together and expecting the shoppers to sort it out. This does not mean, however, that it cannot all be done in the same building.

Perils of Promotion

Given the predominance of the quick-trip shopper, how important are traditional promotions? Promotions are designed for stock-up shoppers, not for quick trippers. If shoppers are only buying a handful of items, promotions probably don’t have their desired effect in either attracting them to the store or generating sales inside. In fact, in a 1997 study of 300 randomly chosen shoppers in four retail chains, Glen Terbeek found that consumers were unaware that 51 percent of the promoted items they had purchased were on sale; the discount had no impact on their buying behavior.

Of those 49 percent who were aware of the promotion, 40 percent would have bought the item anyway; 37 percent switched from another brand, and only 23 percent purchased product “incremental” to their regular buying behavior. Terbeek’s conclusion: “Trade promotion is unproductive, disruptive, and complex, with a dubious return on investment for anyone. Specifically, hidden costs are higher, and benefits much lower, than participants imagine.”5

The hidden cost of price promotions is also emphasized by Rui Susan Huang and John Dawes in their paper for the Ehrenberg Bass Institute for Marketing Science. Analyzing 3,000 price promotions, they found that the promotions had a hidden cost: the profit margin forsaken on sales that would have been made at the normal price, which they call the “baseline” volume. In many cases, the baseline volume that is sold cheaply is twice as much as the extra sales arising from the price promotion. As they write, “Plainly, many price promotions result in a price reduction on significant amounts of inventory that would have been sold anyway…. This means that marketers are paying a heavy price for making some extra sales from price promotions—for every extra sale, they are often giving away margin on another two times as much volume (or more). So while many marketing people and trade sales teams say ‘price promotions work,’ these promotions have massive costs in foregone margin on sales that would have been made anyway, at a normal price.”6

Of course, as we will consider later, the promotions may have more to do with the relationship between the retailer and manufacturer than the retailer and shopper. Even so, they are ostensibly designed to increase sales and seem to be less effective than expected in this task.

The Big Head and Long Tail

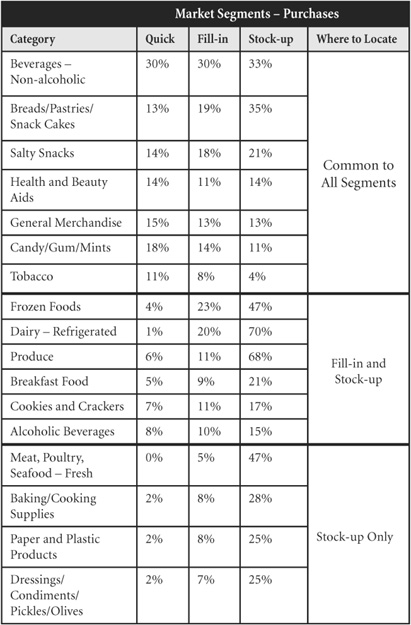

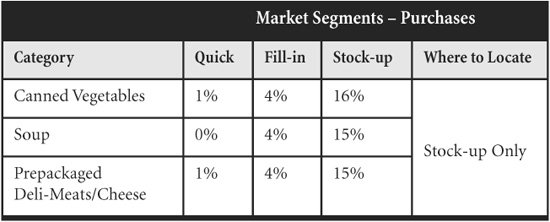

Once the behavioral groups are identified, it is important to match the groups to their distinctive purchases. For the segments identified in this study, the share of shoppers who purchase something from each of the listed categories is shown in Table 1.2. In other words, once shoppers “group themselves” by the behavioral measures, we can look at the resulting market segments to see what they bought, as clues to what we should offer to each group.

Table 1.2 Matching Groups to Distinctive Purchases

Given most stores’ focus on stock-up shoppers, it is not surprising that they are poorly designed for the quick trip. Stock-up and fill-in shoppers are looking for the same products—just expanding the set. We want to focus on, at most, a few thousand items that are needed to satisfy perhaps 90 percent of shopper needs. Moreover, because we will deliver this merchandise to all shoppers very quickly—near the entrance of the store—we expect them to pay for the convenience. So pricing will not be promotional, but rather we will focus on premium brands, quality, and freshness.

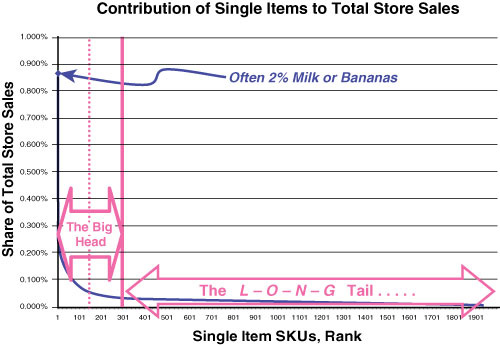

This is not how most retailers think. Warehouses typically offer in the neighborhood of one million different items that retailers could offer for sale in their stores. The retailers have wisely selected a mere 30,000–50,000 items to offer in your stores. But the typical customer’s household buys only a total of 300 to 400 distinct items in an entire year. And they buy only about half of those on a regular basis. Those items purchased over and over, day in, day out, week in, week out, constitute a really short list. In fact, 80 items may contribute 20 percent of a store’s total sales, with milk and bananas typically vying for the top slot at supermarkets (see Figure 1.1). A thousand items contribute half the dollar sales. (The same phenomenon holds for other classes of trade.) As noted here, those few items generating the lion’s share of sales are referred to as “the big head,” while those thousands of other items—and they do generate significant sales—are referred to as “the long tail.”

Figure 1.1 Contribution of single items to total store sales

Heads You Win

Winning always involves making careful distinctions. There are a few crucial distinctions in retailing that largely define success. This distinction between the big head and the long tail could be the single most important distinction to make in terms of managing the range of merchandise that retailers carry. Yet we observe many retailers stirring the two together indiscriminately, in an attempt to sell more of the long tail. Selling more of the long tail is a good idea but not at the expense of penalizing the big head.

Wired magazine editor Chris Anderson has pointed out that online retailing makes the long tail an important business. Online retailers can profitably stock and sell small numbers of niche products rather than only concentrating on the hit products that constitute the largest number of sales. Booksellers such as Amazon can stock an obscure title alongside The New York Times bestsellers. The many small sales of these niche titles add up to a large return for the retailer.7 There is some debate about whether this attractive theory holds true even in the online retail space, as pointed out in a detailed study by Anita Elberse of Harvard Business School.8 In bricks-and-mortar stores, however, the case is clear for focusing on the big head.

The reality is that it is easier to increase total sales of the big head than it is to increase sales of the long tail. Focusing on the long tail is equivalent to trying to get more people to shop on Thursday, rather than focusing on how to serve the Saturday crowd better and more efficiently. Slight increases in Saturday performance per shopper are worth a good deal more than lots of additional weekday shoppers. In the same way, modest increases in per-item big head sales are worth much more than large long tail sales increases, scattered across the massive range of products. Help your winners to win more and bigger. It will give you the resources to selectively focus on the long tail more appropriately.

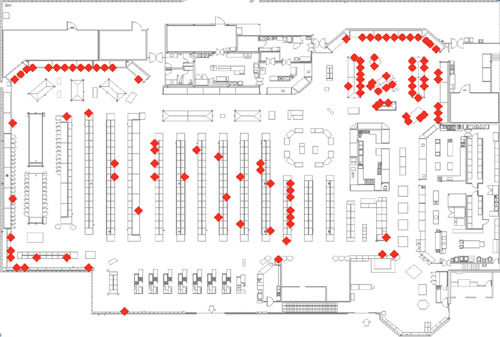

Many retailers hide the big head, as shown in Figure 1.2. This is a map showing the exact location of those top 80 items from the big head for this particular store. As expected, there is a significant collection in the produce section—upper right—and in the dairy—upper left. Otherwise, the big head is pretty well scattered about, as the retailer attempts to sell more long tail by “hiding” the big head among those many thousands of items of very limited interest to the shopper.

Figure 1.2 Where the big head is hiding

The net result of this is a very large loss in big head sales, coupled with angst, frustration, or ennui on the part of the shopper. Don’t worry: There is an important role for the long tail—and there are valid justifications for “SKU proliferation,” “range growth,” and promotional fees to support the long tail—but killing off sales of the big head is not one of them.

In addition to making it harder for shoppers to find “big head” products, a proliferation of SKUs also contributes to the problem of out-of-stock items (stockouts). Increasing from three SKUs to 10 will not necessarily increase sales because it is harder to manage inventory and avoid stock-outs. Roughly 8 percent of store sales are lost due to stockouts, and greater variety increases this risk.

The Communal Pantry

The dominance of quick trips means that retailers are functioning as the communal, neighborhood pantry, offering just what the household needs with emphasis on fresh (quality) products at modest prices.

In the developing world, traditional retailing involves mostly very small neighborhood shops where patrons of limited means purchase only what they need “right now.” These customers cannot afford to stock a pantry at home, so the neighborhood market becomes a communal pantry. In other words, it creates community. Small, family-owned stores, some as small as closets, provide their customers with needs on a daily basis. For example, in India, about 96 percent of the retail marketplace consists of small shopkeepers. Across emerging markets, an estimated 80 percent of people buy their wares from mom-and-pop stores no bigger than a closet. “Crammed with food and a hodgepodge of household items, these retailers serve as the pantries of the world’s consumers for whom both money and space are tight.”9 In Mexico, despite being one of Wal-Mart’s most successful markets, high-frequency stores are still regularly visited by almost three-quarters of the population. Although the average spent is only $2.14 a day, the annual sales total reaches a significant $16 billion.

Small stores catering to the quick tripper in developed markets are also serving as a communal pantry. In this case, the shift is not because of a lack of refrigeration or funds but due instead to a change in lifestyle and a shortage of time. Once the home pantry was the communal focus of the home, but now kitchens have often evolved into a fast-food preparation point to adapt to changing habits, with people grazing, or eating on the run. The household pantry is thus becoming de-emphasized because more customers would rather pick up quality, fresh merchandise in the local “bodega” or neighborhood market rather than stock a home pantry, even though they could easily afford to. So, in this way, the modern consumer is returning to a “communal pantry.” This, of course, has had a consequential effect on buying patterns and subsequently on storage.

So, this is a phenomenon that affects all strata of society, from the rich to the poor: People are visiting stores very regularly, possibly every day, buying what they want when they need it. The retailer takes on the responsibility for warehousing and stocking the essentials that consumers no longer have the space for or desire to stock, and keeps the products fresh and available. This also leads to the homogenization of rich and poor, who visit stores such as Wal-Mart, Costco, and Fresh & Easy. The objective is to have shoppers come in several times a week to pick up dinner, so these stores are essentially acting as a communal pantry.

A 2007 report by Booz Allen Hamilton notes that, after years of hype about “big box” retailing, there is an increasing number of small-format success stories, ranging from convenience stores to discounters to stores that sell basic staples and key grocery items in a cost-effective neighborhood format.10 The report cites three reasons for the trend. First, consumer experience in massive retail stores is becoming increasingly unattractive. Lower-income shoppers, in particular, are uncomfortable in large stores because of impersonal service and the sheer number of items on offer, which underlines their lack of spending power. Second, smaller stores are no longer necessarily saddled with higher prices or lesser quality. Finally, small formats give retailers the chance to have a more intimate relationship with customers and employees, which provides scope for genuine innovation in store and business model design.

This is a global phenomenon and is leading to the breaking down of the divide between the developed and developing world in regions such as Europe and Latin America—a democratization of retail. As the Booz Hamilton Allen report notes: “In Europe’s affluent economies, consumers are looking for convenience items, including meals, to suit their busy lifestyles of single heads of households. Retailing in Latin America, by contrast, is focused much more on low-income and larger families. Part of the explanation for why smaller formats are working in Latin America is that items such as dry pasta, cooking oils, milk, bath soap, and laundry detergent can be acquired in precisely the right quantities for daily use. The stores are, in effect, the customers’ pantries. [italics added]” As these smaller stores have begun to sell high-quality items at low prices, they have come head-to-head with traditional, passive retailers. More important, this shift has tremendous social significance for the countries where implemented, because the product quality has a strong appeal to wealthy customers, whereas the lower pricing appeals to low-income customers. This begins to make retailing a new and valuable community builder. Retail is, once again, at the cutting-edge of social evolution.

Layered Merchandising

Given three emerging features of retailing—the quick trip, big head, and communal pantry—retailers need to rethink how they merchandize their stores. The original idea of the store as a community warehouse needs to be rethought. The importance of quick-trip shoppers argues for a different store design, where the “fill-in” and “stock-up” areas should be considered as extensions of the “quick” convenience area, rather than having the convenience area an afterthought in a store designed for stocking up. Other than representing small selections of the categories specified in the second group (fill-in and stock-up) and the last group (stock-up) in Table 1.2, this convenience area should adhere to the same pricing and selection criteria: high-quality, higher-margin merchandise, delivered more conveniently than that in the long tail. Of course, it is easily possible that the “convenience store” area already is embodied in the promotional store, end-caps, and other promotional displays (see “Managing the Two Stores,” in Chapter 3, “In-Store Migration Patterns: Where Shoppers Go and What They Do”).

The essential element of this merchandising plan is to offer a common area for all shoppers that serves up the merchandise that all segments include in their baskets; then to provide a secondary area that encompasses the first two segments, a third area for the more extended trips that encompass the third segment, and finally, an “everything else” long tail area where a shopper can find almost anything but may need to spend some time looking. The “quick” area becomes the big head portion of the store, where shoppers can spend more dollars per minute (fewer seconds per dollar) than any other part of the store, while the other areas blend into the long tail.

The fundamental concept here is to address explicitly and distinctly the needs of each group of shoppers as they come through the door. Conceptually, this means that retailers should stand at the door of their stores, call out the first segment, and then ask themselves: How am I delivering right away to this group what I know they are going to buy, accepting their cash quickly, and speeding them on their way? The answer to this should be a clear and attractive path that covers all of those items quickly and with clarity—providing just the choices necessary to accomplish the shoppers’ purposes.

For each segment that comes through the door, it should seem as if the store was designed just for them. If retailers can stand at the door and know that they are achieving the Holy Grail for the quick-trip segment, they must proceed similarly with the second segment, and then the third. The key is for each segment to sense that the store was designed just for them. And how is this to be done? Through what we call layered merchandising.

Layered merchandising simply means that the principal needs of each segment are easily and logically found on as short a path as possible between the entry and the checkout. It creates stores within stores. For instance, say that a five-minute trip, by the nature and number of the items, is required for shoppers to acquire all the items they want or may buy. Remember the treasure hunt on which most retailers send customers in looking for the big head within the store, as shown in Figure 1.3. Treasure hunts might be fun for children’s birthday parties, but they are an irritation for a time-pressed shopper.

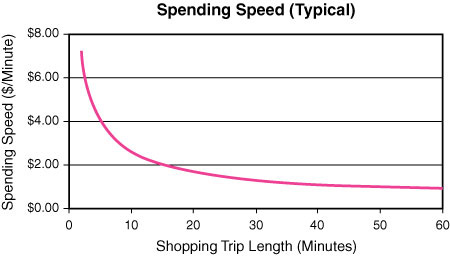

Figure 1.3 Spending speed: Shoppers spend faster the shorter the trip.

Yet retailers think that they are cleverly boosting sales and profits by holding the shopper in the store for ten minutes. They should think again. They force the shopper to spend his or her time walking around the store to find items to buy, instead of spending more time buying. Is this frustration worth it just to get the shopper to walk past a few more items? In reality, the shopper is being told, go somewhere else if you want to shop efficiently—here we intend to frustrate you and hinder you to maybe get a little more of your trade. This leads to fragmentation of the channel as needs are met elsewhere. To reverse this baleful trend requires true customer orientation, beginning with understanding the distinctive types of shoppers (segments) coming in the door, and serving each group efficiently through intelligent product placement.

The Right Paths for the Right Shoppers

Layered merchandising allows the retailer to provide instinctive-distinctive paths appropriate to each shopper segment. That is, when all shoppers arrive in the store, they intuitively recognize, even if subliminally, that all of their most common needs are right around them so that they can efficiently access the “big head” selections from those categories in their pathways to checkout. Some retailers, for example, put a selection of dairy at the entrance instead of forcing quick-trip shoppers to make their way through the entire store to reach the dairy case. The first segment (quick trip) can proceed to the checkout as soon as its members have shopped the common area, whereas the second, the “medium” group (fill-in), needs to pass through and shop a secondary area that should be welcoming and intuitive to them, and again, conveniently on the path to the checkout. The “long” group (stock-up) needs to pass through a third area before passing through the same secondary area as the medium group did, and then to checkout. In every case, the goal is to provide an intuitive, instinctive path, distinctive to the shopper segment, which delivers just what they need from a preselected, high-margin offering, speeding them to the checkout.

The path outlined here would deliver a high volume of sales to shoppers from the 2,000 to 4,000 items they are most interested in, with no compromise of margins. Selective margin reductions are reserved as motivation to entice shoppers to look at more complete selections of the specified twenty categories, plus all other categories, in the long tail portion of the store. But this approach can only be pursued if the retailer recognizes the different segments, understands what they buy, and designs the store accordingly.

There are other motivations/inducements for shoppers to extend their trips beyond the convenient, higher-margin area. One obvious motivation is to benefit from a much wider selection of merchandise. Both price and selection benefits for the long tail can be advertised in the big head portion of the store, without eroding the convenience of the big head experience. Successful execution of such a communication plan will obviously affect the success of the long tail, without compromising the big head. Retailers need to manage not just the big head versus the long tail, but simultaneously offer the long tail to shoppers engaged in big head purchases.

The problem here is somewhat analogous to managing quick trippers at the same time as stock-up shoppers. As noted before, quick trippers are stock-up shoppers, just not on a stock-up trip at the time. So the challenge is to predispose a “soft drink and personal care only” buyer on this trip to return to purchase their laundry detergent or other staples at this store. This problem is one of connecting a single shopper’s quick trip with the same shopper’s later stock-up trip.

Purchase Modes and Selection Paradigm

We also need to recognize that shoppers can be in different purchase modes, and this leads to different selection paradigms. First, the modes can be planned or opportunistic. Some purchases are carefully decided based on shopping lists, research, or careful planning. Others are opportunistic, responding to chance meetings with products in the store.

At the moment of purchase, there are also different types of decision making. Some decisions such as repeat purchases are instinctual, not involving the conscious mind. For these, presenting the shopper with the 100 or so SKUs is the most important factor. Other purchases are decisional, through evaluation and selection, so the use of shopping lists or reminders to buy can help to trigger a decision.

There are also two ways that shoppers view purchases within their trips. The first is that the purchase is mostly not pleasurable or fun, but strictly a chore and should be completed as quickly as possible. The second is a hedonic view, where the purchase is pleasurable, and they might enjoy a leisurely purchasing experience for the item.

Spending Faster

The mismatch between store design and shopper segments, particularly the hiding of big head items in the long tail areas, leads to a great deal of wasted time. How much time is only apparent through careful observation of shoppers. We have found through our research that shoppers spend only 20 percent of their time in-store actually selecting merchandise for purchasing. Because pretty much the sole reason a shopper is in the store is to acquire merchandise, and that pretty well aligns with the retailer’s reason-for-being, too, this represents a tremendous failure. This means that 80 percent of the shopper’s time is economically nonproductive—largely wasted! This single fact has huge implications, because time is money, and we are obviously wasting a lot of it. (This fact lies at the root of my own focus on seconds per dollar as the single most important productivity measure for shopping.) Simply making that nonproductive time productive might give retailers five times the sales.

One of the things that gives me confidence in these recommendations is that there are actually multiple streams of evidence coming together that all support the observation that an awful lot of sales are left in the aisles. For example, consider the average walking speed of shoppers on different kinds of trips. Counter-intuitively, quick trippers’ average walking speed through the store is much slower than the stock-up shoppers. This is a direct consequence of the fact that all the shopper’s time in the store can be divided into two buckets:

1. Now I am standing at the shelf, selecting merchandise for purchase, and walking very slowly, if at all (<1 ft/sec.).

2. Then I am looking for the next merchandise that I might be interested in buying, and hurrying along trying to find it, walking quite quickly (1–4 ft/sec.).

So quick trippers have a lot less wasted time than the stock-up shopper, and as a consequence spend their money a lot faster. Remember that shopper seconds per dollar is one of the key measures of retailing success, so shoppers spending money more quickly ultimately leads to greater overall store sales. As shown in Figure 1.3, the data show that shoppers spend faster on the shorter trip, as a direct consequence of them doing less walking about and more actual acquiring of merchandise. In contrast, a Wharton School study called “The ‘Traveling Salesman’ Goes Shopping’” highlights the tremendous inefficiency of the typical long shopping trip.11

As noted in the Introduction, in addition to focusing on the large head, the other massive angst reduction at Stew Leonard’s comes from having only one, single aisle, that wends its way through the entire store. This is a wide, serpentine aisle that essentially transports every shopper through the store, introducing them in the same order to all of the merchandise there. This virtually eliminates navigational angst. Whereas the typical store is worried about how to get the shopper to the right merchandise—with sales flyers, specials, and flashing lights—Leonard already knows where his shoppers are going and can put the right products in their paths.

For a wide variety of good and valid reasons, everyone is not going to run out and build a “Stew Leonard” kind of store. There are many possible models. The point is not for retailers to copy a simple formula—if everyone is doing it, it becomes less competitive—but to understand the principles that drive extraordinary sales, and leverage those principles in their own operations. In addition to the serpentine design used by Leonard, other effective store designs include the enhanced perimeter, the inverted perimeter, the compound store, and the big head store, as we will explore further in Chapter 3.

Conclusion: Dual Chaos

Matching these diverse segments to a broad set of products—in a way that works for shoppers, retailers, and manufacturers—is a “dual chaos” problem. There are a multitude of types and varieties of people (chaos 1), as well as a multitude of types and varieties of products (chaos 2). The question is how to match the people with the products. In the bricks-and-mortar retailing world, it’s not possible (yet) to do an exact one-to-one match. The store cannot be reconfigured to personal tastes every time a shopper walks in the door. As much as retailers might like to customize their stores for every single shopper, this is not operationally practical. So, the best thing a retailer can do is create a “variety” of shopping experiences addressing the distinctive needs of groups of shoppers.

Organizing shoppers into groups is what segmentation or clustering is all about. Although we have considered the three broad segments that have emerged across many retailers, each retailer or store will have more specific insights into how people shop in their stores. There are two general problems of most shopper segmentation. The first is that most of these schemes result in far too many groups of clusters for practical in-store use. Retailers can respond to a small number of large groups inside the store far more intelligently and in a more targeted way than they can to a large number of smaller groups. However, in defense of segmentation schemes producing larger numbers of groups, these may be effective outside the store, where various advertising media may be targeted distinctly to more varied groups.

The second problem is that most segmentation schemes are based on a wide variety of psychographic and demographic data, which although collected by surveys and other research, are not obviously related to in-store behaviors. The goal of the store is to organize the chaos of shoppers into groups and to organize the chaos of products into groups, and then to introduce the appropriate groups of people to the appropriate groups of products. So, in reality, we’re interested in grouping the shoppers by their behavior in the store rather than by their attitudes, opinions, or even need states.

Generally, such characteristics as age, sex, and others inherent to the individual shopper are subsumed. Attitude, of course, is less fixed, but has been given a great deal of consideration in many segmentation schemes. This certainly includes such things as need states and other transitory mental conditions. Although individual characteristics and attitude criteria are of great value in planning outside-the-store communication strategies (advertising), they are more difficult for store management to actually respond to effectively.

Behavior is the critical in-store factor. It is widely recognized that it is more reliable to observe what people do than to ask them what they do. In other words, if behavioral data is available, it will generally be more reliable and relevant than the shoppers’ attitudes and memories. After all, in the end, the only thing that matters is whether the shopper buys—a strictly behavioral matter. Alexander “Sandy” Swan of Dr. Pepper/Seven Up, an early supporter of PathTracker™ studies, once told me: “I don’t care whether the person buying my product is a 60-year-old man who drives up in an $80,000 BMW, or a 17-year-old pierced teen who arrives with her friends in a beat-up VW. All that matters is that they buy.”

Endnotes

1. Andrew Martin, “Miles of Aisles for Milk? Not Here,” The New York Times, September 10, 2008.

2. “The Rise of Lidl Britain During the Credit Crunch,” The Telegraph, October 9, 2008.

3. Cecelie Rohwedder and David Kesmodel, “Aldi Looks to U.S. for Growth,” The Wall Street Journal, January 13, 2009

4. For the more technically minded, arriving at the clusters in Table 1.1 is based on a formula that calculates the discriminants, which are complex combinations of the variables chosen. There are mathematical ways to judge which variables will help to discriminate among the members of the group. Using the variables that show the differences among the clusters most clearly suggests that those are relevant differences. Although any number of discriminants can be computed, you are really looking for the lowest number that still gives a reasonably good description of the data. Those variables that have the most impact can then be used to describe the emerging clusters. A word of warning: The results are based on the variables selected, so they will reflect the analyst’s judgment in selecting variables, as well as the available data.

5. Glen A. Terbeek, Agentry Agenda, The American Book Company, 1999, pp. 32–34.

6. Rui Susan Huang and John Dawes, Price Promotions, Ehrenberg Bass Institute for Marketing Science, 2007, Report 43.

7. Chris Anderson, The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More, New York: Hyperion, 2006.

8. Anita Elberse, “Should You Invest in the Long Tail?” Harvard Business Review, July-August 2008.

9. “P&G’s Global Target: Shelves of Tiny Stores,” The Wall Street Journal, July 16, 2007.

10. Ripsam, Martinez, Navarro, 2007, Booz Allen Hamilton.

11. “The ‘Traveling Salesman’ Goes Shopping: The Efficiency of Purchasing Patterns in the Grocery Store” (http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article. cfm?articleid=1608).