8

Multicultural Retailing: An Interview with Emil Morales, Executive Vice President of TNS Multicultural

In addition to new technology that is changing retail, shoppers themselves are changing, with shifting demographics and the rise of multicultural retailing. This century is seeing dramatic shifts of population, and retailers are only just beginning to wake up to the changes they need to make to capitalize on these changes. In this interview, Emil Morales, executive vice president of the TNS Multicultural practice and general manager of their Centers of Excellence, explores this changing landscape, with a particular emphasis on the Hispanic population in the U.S. as an example of the global challenges of multicultural retailing. As he points out, many of these shoppers are coming from traditions of shopping at very small local stores, where clerks take a very active approach. Retailers need to take an active approach to meeting this segment, particularly with the added barriers of language and culture. Similar changes are occurring whether the multicultural customer is a Middle Eastern Muslim who has transplanted to Europe, a Hispanic immigrant in the United States, or a rural Chinese moving to one of the great cities of China. Morales examines how retailers need to change their thinking, product offerings, and store designs to reach this growing market.

This book looks at how retailers need to move toward active retailing by anticipating and responding to shoppers’ needs. What does active retailing mean in the context of multicultural marketing?

Morales: First and foremost, you must understand the cultural norms, values, and needs of these consumers. Moreover, it is essential to know their geographic concentration and key demographics to provide the right products and services via the proper channels. Most new arrivals from developing countries are moving from a “service” retailing experience in small shops to one of self-service, which can be very impersonal. The developing world is characterized by neighborhood shops, where proprietors are hands-on and active in a very personal way. Rather than being educated about products and services by their local grocer, they are now required to learn in a physical environment, as well as a language and cultural setting, which is unfamiliar and even intimidating. This certainly slows progress for the retailer, manufacturer, and consumer. This means immigrants from developing countries may expect more active approaches, enabled by both new technology, such as smart carts and old tried-and-true methods that respond to their needs.

What are some of the challenges facing the multicultural shopper that retailers need to be aware of?

Morales: For those of you who have experienced foreign travel to a non-English speaking country, there inevitably comes a time when you need to make a purchase. You might be purchasing a power converter in an electric supply store in Paris, searching for a contact lens case in Amsterdam, or buying food items for a picnic lunch in Santorini. Needless to say, the experience creates feelings of both excitement and anxiety. In our daily lives, we rarely think about the shopping process. However, in a foreign country, the process takes on new meaning, as there are a number of steps to be considered. First, there is the language barrier. Even if you know what to call the item, you certainly will not pronounce it like a native, and you also need to express your search with more than a single word. Second, you need to figure out where to find the item, as you have likely discovered that where items are sold conforms to the norms of each country. Of course, figuring this out requires still more linguistic challenges. Once you know where it is sold, if you are lucky, you can simply walk there. If not, you need to deal with the logistics of travel to your destination. And then finally, you have to work through the actual cost in the local currency, especially if you cannot see the numerals on a display at the point of sale.

I count myself fortunate in having had such experiences, but it is also invaluable in helping to place myself in the shoes of the multicultural shopper. Although my struggles were temporary and also provided a sense of adventure and discovery, for those who have to maneuver the “stranger in a strange land” scenario every day with far more limited language and coping skills, it can be an exhausting and stressful experience. In fact, one only has to look at the number of American tourists who flock to a Starbucks in overseas locations to understand the importance of familiarity with the shopping process, as well as a product or brand. There is certainly an expectation that they will have what I want, they will understand me, and I will be in the company of like-minded individuals with whom I have something in common. It should come as no surprise that in the U.S., multicultural segments will behave the same way.

What is the significance of the Hispanic segment in U.S. markets?

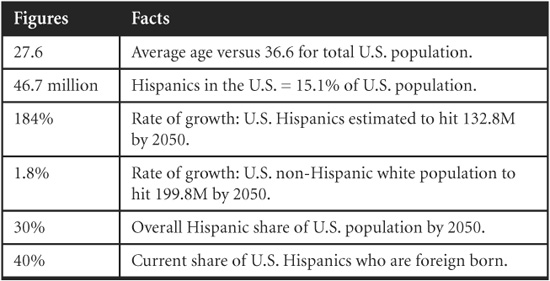

Morales: Without question, one of the transformative events of the last several decades has been the explosive growth of the U.S. Hispanic population. Not only due to the sheer numbers, but most important, because it has caused an intense examination within the U.S. of our future national identity. Although Hispanics are often highlighted, the rapid growth of the U.S. Asian population and the emergence of a strong African-American demographic, as was evidenced in the recent presidential election, have a huge impact on U.S. society. The demographic shifts taking place are powerful and inexorable. By 2050, approximately 225 million people in the U.S. will be part of a multicultural segment. We’re talking about almost a quarter of a billion people. It’s a number that many marketers and retailers have yet to grasp. In fact, if you could convince these 225 million people to give you a dollar a day for a year, your total would be over $82 billion. Surely, a number like that will get retailers’ attention. As shown in Table 8.1, according to the 2008 U.S. census, there are currently more than 46 million Hispanics in the U.S., about 15 percent of the population. The population is growing very rapidly. By 2050, Hispanics are expected to account for 30 percent of the U.S. population.

Table 8.1 Characteristics of the U.S. Hispanic Population

Source: U.S. Census 2008

What makes this segment attractive to retailers and manufacturers?

Morales: By any measure, the U.S. Hispanic segment would qualify for serious investigation or investment. The Selig Center for Economic Growth in Georgia estimates that U.S. Hispanic buying power will reach $1.2 trillion by 2011. This figure exceeds by far the Gross Domestic Product of Mexico. McKinsey & Company, in their top trends published in 2006, stated that by 2015, the U.S. Hispanic population will have spending power equivalent to 60 percent of all Chinese consumers. These are large numbers and have already drawn the attention of retailers and manufacturers from across the globe, in particular those from Spanish-speaking countries, looking to leverage their brand equities in the U.S. It has also drawn interest in the investment community from companies such as Goldman Sachs, which has set aside $50 million to fund companies focused on marketing to fast-growing multicultural segments.

How can manufacturers and retailers seize this opportunity?

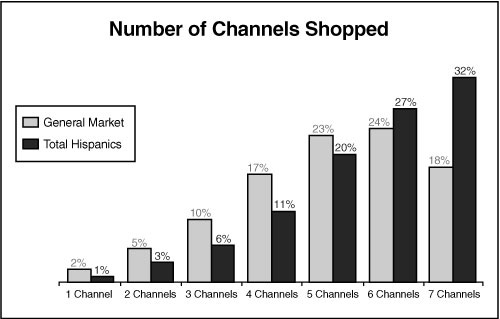

Morales: Serving the needs of U.S. Hispanics is not a simple task. Although all consumers have certain unique features of which retailers need to take note, U.S. Hispanics present their own set of challenges. For example, our research shows that close to two-thirds of U.S. Hispanics are either Spanish-dominant or Spanish-preferred. This translates into varying degrees of comfort not only with the written and spoken word, but also with entering environments where they may feel ill at ease. As we discussed, understanding cultural norms and creating welcoming environments are central to attracting and retaining these consumers. Their cultural norms dictate what they seek not only in terms of products, but also from retail environments. Figure 8.1 shows data from the most recent TNS Shopper 360 syndicated report. As you can see, U.S. Hispanics tend to shop many channels versus their non-Hispanic counterparts.

Figure 8.1 Channel use

Why do Hispanic customers shop so many channels?

Morales: This is due in part to the exploratory nature of their shopping behavior. You need to keep in mind that as many as 60 percent of U.S. Hispanics are foreign born and, therefore, are unfamiliar with the concept of so many channels. Approximately 65 percent of U.S. Hispanics come from Mexico and from many rural areas. Essentially, their exposure to channels was quite limited. As a result, they are often eager to learn what channels are available to them in the U.S. and what benefit each one offers.

Shoppers with limited exposure to U.S. culture are most likely to settle in communities where their language is still spoken and where many of the elements of their culture remain familiar to them. They might frequent local bodegas, or in the case of Mexicans, tienditas—small neighborhood stores. As their needs for more sophisticated products and services emerge, they will likely travel with a trusted friend or family member to a larger outlet—a supermercado (supermarket). There will likely still be people there who speak Spanish, the store will have the right cuts of meats and familiar brands—but there will be more of them. The environment will still be comfortable, however. Once they begin this process, it’s not long before they move on to supercenters, club stores, and mass merchandise outlets, malls, and beyond. This is all a part of their enculturation into shopping in the U.S. However, getting them to visit and getting them to buy and remain loyal to the channel is not the same thing.

Trust is critical. The top reason given for store selection by U.S. Hispanic customers in the TNS Hispanic Shopper 360 study was “It is a store I can trust.” In contrast, in the general market, the top reason cited was “could get to this store quickly.” Clearly, the issue of trust is still central for Hispanic consumers. It’s not too hard to think about why this might be the case. We all want to feel welcome and comfortable in our environment. We also want to know that if something goes wrong, we will be understood and treated with fairness. What these data seem to imply is that there is still room to improve in communicating a sense of trust to these Hispanic consumers. After all, we know that smaller bodegas and tienditas tend to charge higher prices and have less selection than larger-format stores, yet Hispanics still shop there. We know that the feeling of trust and comfort is important because they are willing to pay more for that comfort along with the convenience.

Given the popularity of tienditas and other small stores, do U.S. Hispanic shoppers have any interest in larger stores?

Morales: From our Hispanic Shopper 360 data, we know that U.S. Hispanics find mass merchandise, drug, convenience, and club stores attractive. We also found that supercenters in markets in Texas and Miami are visited frequently by Hispanic shoppers. There’s a lot to discover, and concepts such as everyday low pricing (EDLP) are attractive, particularly for those with large families. However, once they are in the store, they need to be able to find what they’re looking for and be assured that it’s the right product for the job. Because U.S. Hispanics have a lower median income than the overall U.S. population, they cannot afford to make product mistakes. This means the power of known and trusted brands can be a powerful guide in their decision making. However, this does not mean they are not open to other brands, which is why it’s essential that investment in building and maintaining brand awareness takes place.

At some point in their acculturation process, they absolutely move to the next level. They will visit a Wal-Mart, a Food 4 Less, or a Target, one of the superstores that doesn’t just stock grocery items. That’s when difficulties may arise. From a friendly and comforting environment, these new shoppers find themselves in a store with potentially limited recognition of Hispanic consumers as a distinct group. For example, the service staff might not speak the language. The signage and often the packaging will be only in English and they might have difficulty in locating someone who looks like them to ask for advice. The store selection may have limited appeal. As the difficulties mount up, these shoppers end up frustrated by their experience.

None of these obstacles is insurmountable individually, but taken as a whole, they can be formidable. One solution can be to take along someone who speaks English, which is why you often see Hispanics shopping together in groups, but this is not always practical. Retailers can further disrupt the process if they suddenly change the mapping of a store without apparent guidance. In one focus group session, a woman spoke about how she used to frequent Costco and seemed happy with her shopping experience. One day, they changed the location of items she had been familiar with, and she could not find a Hispanic to explain where the items had been moved. As she did not want to feel embarrassed given her English proficiency, she left the store, never to return. She now shops at a store with more visible Hispanic workers to avoid a similar situation. Costco never knew they lost her, or why.

How does this use of many channels affect the way Hispanic shoppers plan to shop?

Morales: You’ve already talked about how U.S. shoppers in general rarely plan their shopping trips. If anything, this is more of an issue for Hispanics. They shop more frequently than the norm, using the store as a pantry and, therefore, don’t see the need to make lists.

In our survey, only 36 percent made and brought shopping lists to the store. Many had a specific brand in mind when they went shopping. So what influences their product choices? There’s a lot more word-of-mouth referral for products because that’s one of the greatest sources of information, particularly if you’re struggling with the language. Store circulars, meanwhile, play a very important role in the shopping process for grocery, drug, and even department stores. About a quarter looked at the store circular. This is a consumer segment that does not do online comparisons as such very often. Instead, they rely on printed material.

One area that has, to date, been under-exploited by retailers is coupons. Currently, they are either not being directed as heavily to Spanish-speaking consumers due to distribution challenges, or go unused due to Hispanics’ unfamiliarity with the concept. Moreover, our most recent TNS Hispanic Shopper 360 data also shows that U.S. Hispanics are not major coupon users. In fact, they ranked “I redeem a lot of coupons” very near the bottom of a list of attributes, whereas their general market counterparts ranked this same attribute near the top quartile. Clearly, there are issues of education that would benefit retailer, manufacturer, and the consumer in this area. Sometimes, even if they want to use them or have them in their bag, they just forget—and then the coupons have expired. If this happens on a number of occasions, they get disenchanted with the whole process and will not re-attempt. An additional problem, for those with more limited language proficiency, is the very real fear that they hand a clerk the coupon and then start to receive questions about it. This causes them to stand out or be embarrassed if they have limited language proficiency. As we discussed, culturally, that’s not something that they want to do.

In our recent Hispanic Shopper 360 data, we discovered that 65 percent of Hispanics were influenced by in-store offers. This was more than twice the impact of general-market shoppers. So, if coupons seem to have limited appeal, it would make sense to develop and invest in more tactical in-store efforts.

Retailers should also work with manufacturers and community-based organizations to sponsor classes on how to save money or be savvy shoppers that would include both frequent shopper card and coupon use. They could produce printed FAQs in both English and Spanish, which saves money and ensures many potential users.

How does the U.S. Hispanic market react to loyalty cards and other mechanisms to collect customer data?

Morales: We know that growth in many multiples is achieved by learning more about existing customers. The rise of Tesco in the UK, for instance, has been built on the back of the Tesco Clubcard, its loyalty card. In the U.S., however, targeting the Hispanic market in this way is likely to present problems. Loyalty cards are very under-represented in such ethnic groups because of a reluctance to provide personal data and information. The institutional trust that retailers have come to rely on just does not exist and creates a barrier for those who rely on loyalty cards as a tool. In their minds, Hispanics simply want to make their purchase at the best possible price and do not understand why they need to provide the retailer with their personal details to do so. In fact, I would not be surprised to see a similar point of view emerge across the board for shoppers in general, given privacy concerns.

This problem eases further up the acculturation curve, but for those who are new to a country—or who might have entered illegally—giving personal information is a no-go. Even Puerto Ricans, who are U.S. citizens from birth, may be reluctant to do so. Such populations are also likely to opt for unlisted phone numbers—behaviors that make it difficult for retailers to gather valuable data. To compound their problems, Hispanics may borrow cards or get someone else to buy for them—not altogether helpful for a retailer trying to identify patterns of buying behavior. To some extent, this reflects a deep-seated cultural norm related to a sense of distrust of institutions.

How does culture drive shopping behavior?

Morales: Culture plays a critical role in the behavior of multicultural and, for that matter, all consumers. In their excellent book, Hispanic Marketing, published in 2005, Felipe Korzenny and Betty Ann Korzenny highlight how marketers need to understand culture to develop deeper emotional connections with Hispanic consumers. Of course, this link to deep cultural understanding applies to all consumers and not simply Hispanics.

In their work, they speak of culture as “the cluster of intangible and tangible aspects of life that groups of humans pass to each other from generation to generation.”1 They use an iceberg as a metaphor for culture, with two aspects: the “objective culture,” which appears above the surface, and “subjective culture,” which is hidden below the surface.

Foods, music, and clothing are examples of objective culture. In the U.S., the objective culture might include hot dogs and hamburgers, rock and roll, and jeans and t-shirts. For Caribbean Hispanics, these tangible external symbols of culture might include arroz con pollo, salsa, and Guayabera’s. Although these external cultural elements are quite different, they are nonetheless highly acceptable and taken-for-granted norms within each culture.

You mentioned the second aspect of culture, subjective culture. How does this affect shopper behavior?

Morales: The second aspect and by far the most important to marketers in my opinion is “subjective culture,” a set of beliefs, values, and attitudes that influence how we interact with the world and how the world interacts with us. These aspects are deeply connected to emotions. This emotional connection is exactly where retailers, manufacturers, and all who want to connect with these consumers should focus their efforts. It’s not simply that Hispanics tend to have larger families that is important, but rather that your place of business is seen as a welcoming and safe environment where families are welcome and supported with items such as temporary play areas for children, freeing mom to shop at ease.

This notion of connecting to the elements of shoppers’ subjective cultural norms and supporting them with objective norms can prove to be a very powerful activator for retailers and marketers. If you have not yet undertaken an exercise to understand the deep emotional connections of your multicultural consumers, it should be a top priority. We will discuss examples later where cultural differences rise to the surface, enabling you to develop products or messaging that appeal to emotional connections.

It is, therefore, essential that before you undertake any serious effort to appeal to multicultural consumers that you truly understand their deeply held beliefs, attitudes, and values. These should guide your development processes whether they are centered on store environment, product development, or advertising and promotion.

In understanding cultures, remember that cultures are not monolithic and will vary even within groups by country of origin. Subjective culture gets to the emotional connection that drives deeply rooted psychological needs. Focus time on deep understanding of beliefs, attitudes, and values of each culture of interest. Then, use these learnings as a touchstone to make investment decisions and guide action.

How does the process of acculturation unfold and what do retailers need to know about it?

Morales: Acculturation is the process by which we measure how one culture has adopted the mainstream behaviors of the dominant culture. In the past, it seemed inevitable that people gradually lost touch with their original culture when they put down roots in a new country. However, with significant changes in the thinking about race and ethnicity for many portions of American society, immigrants are no longer forced to adopt the dominant culture. In addition, it is easier than ever before to retain links to homelands. The ability to access print, television, radio, and online media from their country of origin (or at least in their native language) makes it easier to stay connected to their native culture. Our studies found that bilingual Hispanics watched an average of about 3 hours of Spanish television a week (and about 17 hours of English language TV), whereas Spanish-dominant immigrants watched more than 15 hours of Spanish language television (and about 8 hours of English). The presence of large and vibrant support communities also slows the pace of acculturation. Newcomers can subsist quite nicely within relatively small or self-contained communities, continuing to shop at places where they feel comfortable and are welcome. These links may eventually weaken from the first, to the second, and the third generation, but it is a slow and gradual process. My post-election belief is that with an even stronger recognition among these groups, you can have both tight links to your culture and success in America. President Barack Obama is proof positive.

Given the close family relationships in Hispanic culture, how do retailers need to respond?

Morales: Smart retailers latch on to the fact that a welcoming family environment is key. Hispanic Americans tend to shop as families or as groups, and there are often children in tow because the family size/structure is much larger than the median for the U.S. Retailers such as H.E Butt, with its “kid-friendly” zones, have been hailed as a success in marketing to the Hispanic consumer. They have created a tortilleria area, a great concept and very much central to the culture, where they make approximately 10,000 fresh tortillas a day. Bashas, a chain with an Arizona focus, has also had success with the same type of format. It cares for 6,000+ kids a week at its Cub House while parents shop. All of this contributed to H.E Butt being named “Retailer of the Year” a few years back by Progressive Grocer. Wal-Mart has also been moving in this direction, particularly in Texas, and has even added a Central American chain, Pollo Campero, in some of its stores. It makes it easy to spend lots of time in their stores.

What issues of product selection or packaging do retailers and manufacturers need to address for this segment?

Morales: Planning for a shop can present problems for shoppers who are used to products in one shape or form in their country of origin, yet which have undergone a radical transformation in their new home. They may be familiar with soap and body gel in bar form, for instance, which is now viewed as outdated. Or they may be used to buying laundry powder, when in the U.S., it’s the liquid version that is the most popular, for example. They may even be used to seeing much larger packages, instead of more concentrated products in small packages, largely prompted by environmental concerns. So, there are obvious opportunities for retailers and producers to make sure that they’re communicating about form, use, and benefits adequately to this population.

There are also product genres that Hispanic shoppers are more likely to avoid, such as frozen food or packaged foods in a box that require microwaving. The culture is still such that it often demands homemade food as it’s still essential to mom’s pride to care for her family appropriately, and pressure comes from both family and peers. Cooking a meal for your kids shows your love for your family. Hispanic moms are willing to take shortcuts, but only if quality and flavor are not compromised—as with chopped tomatoes for salsa, for example. We know that these barriers start to diminish, however, based on the need of “new” Hispanic moms for convenience and kids’ “pester power” and with the length of time in the U.S.

How are companies winning with U.S. Hispanic consumers?

Morales: The companies that have maintained sustained efforts and investment in marketing to immigrant populations are now reaping the benefits. Companies such as Procter & Gamble, for instance, and brands such as Colgate—which is strong in Latin America—have done well. Kraft is another example, as is Heineken, which has seen great growth of late, and McDonald’s in the U.S.

The winners win because they have a strategy, stay the course, and invest in their communities. They focus on building awareness, which we have already identified as central to success with this group. Those who invest in building awareness also invest in their various communities through community events, sports sponsorship, music or arts events, and the like. Some have created cookbooks that are Hispanic-themed. Others, such as AT&T on the wireless side, have converted all their stores in Spanish-language areas so that they have a high Spanish-speaking quotient of employees, materials, and advertising. They recognize the importance of “localization” and invest in all areas that are necessary to generate success, applying established marketing principles to these groups, but they do it step by step.

How successful have manufacturers and retailers been in responding to the opportunity of the U.S. Hispanic market segment?

Morales: The Hispanic population has been growing apace, yet retailers woke up relatively late to the potential. It is only now, when the mainstream U.S. population is experiencing virtually as many deaths as births, that they are gearing up for change. In fact, it is manufacturers who are at the forefront—companies such as Procter & Gamble, J&J, Unilever, ConAgra, and so on—who have been very aware of the shifting demographics and are asking retailers what they intend to do to be more welcoming to these consumers. Now there is a dialogue between the two so that they can both benefit. They have in troduced new products that leverage the brand at lower price points. This represents both good business and cultural sensitivity for the early movers.

Different retailers and manufacturers are at different stages in the process, however. Some are more aware than others, and many are putting off investment in this area from one year to the next. In some U.S. cities, meanwhile, traditional grocery stores have been losing out due to Hispanics taking their wallets to dollar stores, and have, therefore, had to adapt. A store like 99, in southern California, which is a supermarket with aisles and aisles of everything from housewares to laundry to food and refrigerated produce—all for $0.99—is a definite incentive for change.

Such change requires investment, though, and not just in store design and signage, but also in providing well-trained individuals who can communicate with shoppers in their language of choice. In fact, hiring, training, and retaining bilingual employees who possess the needed levels of proficiency and customer skills is proving to be a real challenge for many retailers. Providing the right experience for a trust-based consumer is very reliant on this high-touch quotient, and you need to find and retain the right people to achieve success.

Can you give an example of how a retailer or manufacturer has used an understanding of multicultural marketing and U.S. Hispanic markets to build its business?

Morales: La Curacao, a Los Angeles-based department store, is often cited as an example of a retailer that’s been very successful in appealing to the Hispanic shopper. Credit is seen as the cornerstone of its success, with the chain catering its credit and other services specifically to the needs of Latino immigrants. It is said to approve 75 percent of credit card applications, whatever the status of applicants, by using unconventional and confidential credit-scoring methods and interviewing techniques.

These cardholders then account for the vast majority of the chain’s sales, many of which are consumer electronics, appliances, and furniture. And the card’s rate of interest, though higher than some general-market retailers, proved lower than others—a factor that stirred up the market somewhat. It sparked discussions as to what rates should be charged to people who have less knowledge and proficiency in the market than traditional consumers. Nevertheless, all of a sudden, other retailers came under pressure to develop plans focused on the Hispanic marketplace in the U.S.

Another reason for its success is that it has more salespeople per customer than its competitors, although this can impact pricing. High service standards are another factor. As for the store design, it is colorful with Mayan and Aztec architecture and décor, plus it features Spanish-language signs.

Although the chain reflects an astute understanding of the market, it was not founded by Hispanic immigrants. The founders were two brothers who immigrated from Israel in 1997, Jerry and Ron Azarkman. They understood the immigrant experience and built a store to meet the needs of a very different group of immigrants.

You’ve focused on Hispanic markets in the U.S. How do these insights apply to other markets?

Morales: The learnings are relevant to other countries, and wherever immigration and acculturation is a significant market reality. I recently spoke at a conference in Toronto on “The Changing Face of Shoppers.” After the conference, a Middle Eastern banker who now lives in Toronto approached me. He first thanked me for speaking openly about the opportunity multicultural markets represent, which is not widely discussed. He then went on to tell me how Maple Lodge Farms, the largest chicken-processing company in Canada, had focused on the unmet needs of the Muslim community for Halal-certified foods, which are prepared according to strict Muslim religious requirements. These foods were met with great success by the Muslim community in Canada and elsewhere. On their website, you’ll find a separate link with great information on the company, process, and its branded Zabiha Halal foods. This is proof positive that if marketers invest the time to understand multicultural consumers’ needs, they can profit handsomely by owning the category and establishing a reason to believe from which to introduce new products.

Sometimes the shifts are within the country. China’s economic growth, for example, has gone hand in hand with the rapid emergence of a new breed of consumers there: an urban middle class, increasingly sophisticated, with retailers at the sharp end of demands for higher-quality goods and services, variety, and innovation. Yet this retail revolution would not be enough to guarantee inclusion in this chapter. What makes the difference is that there has been an unprecedented migration from rural areas to the cities, which has grown the size of the second- and third-tier urban retail markets. In addition to higher disposable incomes, there has been a trend toward greater ownership of refrigerators (meaning a daily shop is no longer required) and changing lifestyles (working mothers). As for the retailer, local protectionism may well decrease the efficiency of distribution and supply chains, leading to fewer choices or higher prices for consumers.

Still, since China’s accession to the World Trade Organization, there has been massive deregulation of the retail and distribution sectors and growth. More than 35 of the top global retailers are now in China. With domestic companies, they are catering to this new rush of consumers to the city. This is a multicultural shift within a single country.2

In closing, what would be your top tips for retailers and manufacturers who seek to address multicultural shoppers?

Morales: There are many approaches and subtleties to addressing this market, as we’ve discussed, but some of the core principles to focus on are the following:

• Create a comfortable and welcoming shopping environment: Hispanic shoppers spend more time in stores, often shopping with family, and see the shopping process as entertainment. Comfort is a priority and can be valued over convenience. This can be seen in the ease of shopping (wide aisles, translated signage), kids’ play areas, in-store dining options, or even customer service (where warmth and friendliness are key).

• Understand where these consumers come from: Learn what experiences they were used to in their countries of origin and what their current values are today to understand the familiarity they seek and how to reach them in a culturally relevant way.

• Recognize that Hispanic moms want to be smart shoppers: Give them the opportunity to make smart decisions by providing good value and high-quality products.

• Cater to the entire family: Shopping can be a family activity, with children sometimes doing the translating for parents who are less fluent. Provide an environment where all members of the family can shop and enjoy themselves.

• Go the whole way: Ensure that multicultural efforts resonate by committing to them entirely. Make sure the customer has cultural/in-language support throughout the shopping process and reinforce the commitment with equally relevant marketing and PR efforts.

• Make education a priority: These consumers often are unfamiliar with brands or even entire product categories. Make sure to give the explanation of how products work and ideas on ways to use them. In terms of in-store policies (returns, exchanges, loyalty cards, and so on), explain how they work to create a greater sense of trust and comfort. Remember that multicultural shoppers might be uncomfortable about embarrassing themselves by asking.

• Develop a holistic multicultural marketing strategy: If you already have a strategy, check to be sure it’s still relevant and delivering on its promise. If it’s off target, spend the time to find out why and how to get it back on track.

• Don’t fear in-language communications: Research shows that the vast majority of consumers don’t care if your communications and packaging are in two languages. It is becoming a “taken for granted.” Also bear in mind that if it works for today’s market leaders, it should also work for you.

• Get out there: Don’t simply rely on reports or the occasional focus groups (although they are both useful). Go out and meet with a few of the more than 46 million U.S. Hispanic shoppers (or African-American or Asian shoppers). It will absolutely change your thinking about the potential of these markets for your business.

Endnotes

1. Korzenny, Felipe and Korzenny, Betty Ann. Hispanic Marketing: A Cultural Perspective. Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, UK. 2005.

2. ChinaRetailNews.com. “Investing in China’s Retail Industry,” April 2006, PriceWaterhouseCoopers.