If you are in the market for an LED bulb (and, for argument’s sake, let’s keep the medium screw base bulb separate from LED lighting overall, such as lamps with built-in, non-replaceable LEDs) then there are a number of factors to consider. We’ve covered some of them, and many will be obvious to any consumer: price, appearance, brightness level, power consumption, whether they are dimmable or not, and so on. These are all points that any buyer would consider before purchasing a bulb, regardless of the underlying technology. However, because of the scrutiny applied to solid-state lighting, an examination of the product can be much more in depth than just a casual price/shape/brightness check.

Aside from the aesthetics of any one particular bulb, all buyers should consider something businesses are already acutely aware of: ROI. This is a simple consideration of the fact that while LED bulbs are initially expensive, they are generally cheaper in the long run. This might not have been the case with CFLs—take for example, running in short durations could negatively affect lifespan—but it’s generally the case with LEDs because of two factors. These, as you know by now, are their longevity and their efficiency. What buyers also need to consider, though, is replacement cost. If you have a light that is 25 feet high and you need to rent a scissor lift or hire a handyman with a extendable ladder to change the bulb, then the fact that a bulb should last 20 years means it’s an even better value compared to one that won’t.

One of the great things about lighting, at least if you are a buyer, is that safety-conscious governments and trade organizations take it very seriously. Here in the United States, agencies like the Department of Energy and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) make sure that a bulb’s packaging is covered with all the crucial, test-certified information that consumers need to make their decision. The manufacturers, being the good capitalists and business people we know them to be, will also strive to make sure consumers understand all the benefits and savings that go along with expensive new LED bulbs.

Let’s walk through a typical packaging to see what it can reveal.

In the case of the Philips 409904 Dimmable AmbientLED (Figure 6-1) 12.5-Watt A19 Light Bulb (medium base, A-shape) the first thing that pops out is the color of the bulb—it’s yellow! As previously explained, that’s just the remote phosphor, but the average consumer doesn’t know that so Philips makes it abundantly clear that the AmbientLED is white when active. Not only is “white light when lit” written directly above the yellow bits (Figure 6-2), but the back of the package displays a yellow lamp that is off and a white one that is on. The company fully understands how dismaying the color can be to buyers, and short of selling a bulb that is running off a battery, this is the best they can do.

After that, the premium space on the packaging is directed at clearing the bulb’s next major hurdle: its price. At $26.90 (and an MSRP of $49.99), the AmbientLED isn’t egregious, but it will cost you about 20 times more than a standard incandescent bulb ($26.90 vs. $1.32 for a GE A19 60W bulb). Customers understand that, and it’s Philips’ job to stop people from putting down their product as soon as they spot the price tag. Three pieces of information on the front alone convey this. The first screams, “Saves $130.62 in energy costs” over the 25,000-hour life of the bulb. The second notes that the bulb costs just $1.51 a year to operate, and the last is that it will work for 22.8 years (when used for 3 hours a day). These won’t prevent the bulbs from being expensive, but at least they make it clear that LEDs will be cheaper in the long run.

The packaging also advertises that this LED bulb is dimmable. Not all CFLs can claim that, nor can all LED products. The ability to dim a bulb using the existing controls—which are almost always made for dimming incandescents—is important to many buyers. What’s not explained is just how much the bulb can be dimmed. Will it simply turn off when it hits the 40% mark? Will it have increasing lumen levels from 0% straight through to full power? For an LED bulb to do this it requires a dimmable LED driver, which costs the manufacturer extra money—and they want you to know about it.

But guess what? This still doesn’t ensure the switch you have at home will work. Most dimmers were built to work with high wattage incandescents, so when you move over to a bulb using a fraction of the power, you’ll still be providing the LED bulb with more than enough for it to operate at 100% brightness. CFL/LED specific dimmer switches are available…but your home probably doesn’t have them unless its new or you’ve upgraded. Because it’s both difficult and expensive for manufacturers to design their bulbs to compensate for the cheap, poorly designed dimmers in most homes, they probably will never do this very well. A likely solution is that power companies will subsidize, or even give out, better dimmers for their clients, just as they did when they encountered the problems with CFLs.

In case you’re not familiar with the subsidies, they did, and still do, happen. Companies like Duke Energy regularly give out free bulbs and rebates on bulbs to customers in an effort to get them to consume less energy.

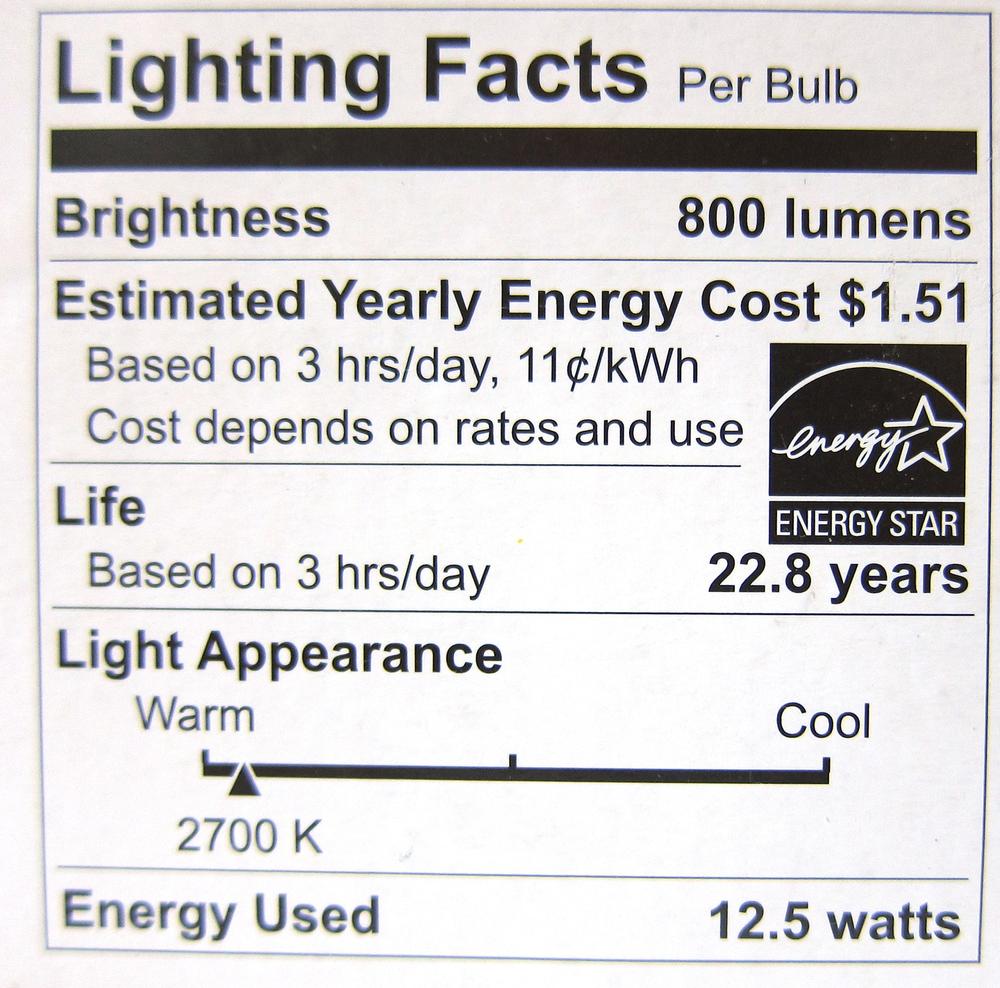

Finally, the front of the packaging also displays the number of lumens the bulb produces (800 in the case of the AmbientLED, Figure 6-3). This is an important part of the move away from wattage as an indicator for brightness and to inform consumers about what kind of performance they should expect.

There is a lot of information on the back of the packaging, including the features, footnotes explaining the claims on the front, warranty, and so forth, but the most important part is the Lighting Facts section. Note its similarity to the Nutrition Facts label that is on any packaged food product you buy in a supermarket. The design clearly states that this is something that is tested, certified, and as free (as possible) of marketing and advertising. This is the part that the Department of Energy cares about and this is the information you can count on when attempting to make an informed decision. In fact, even the size requirements for the Lighting Facts label match those of the FDA’s Nutrition Facts.

The Lighting Facts starts off with the brightness in lumens and then moves on to the estimated yearly energy costs. In this case, the Philips bulb comes in at $1.51, assuming 3 hours a day at 11 cents per kWh. This number will vary based on where the bulb is operated, what time you are running it, and who provides your power. Next up is the lifespan of the bulb (22.8 years), again based on 3 hours of usage a day. After that comes the “Light Appearance,” which plots the bulb’s color temperature on a spectrum that runs from warm to cool. At 2700K, the indicator on this gauge is about 5% from the leftmost point, meaning the bulb is just about as warm as it can be. The final piece of information in the Facts box is the bulb’s power consumption, which in this case is 12.5W.

The Lighting Facts label is required on the side or rear of every lighting product, thanks to the FTC’s 2010 Appliance Labeling Rule. The black and white box on the front that indicates the brightness and estimated yearly energy cost is actually part of the government-mandated label. The label was officially required for use on all lamps sold after January 1, 2012.

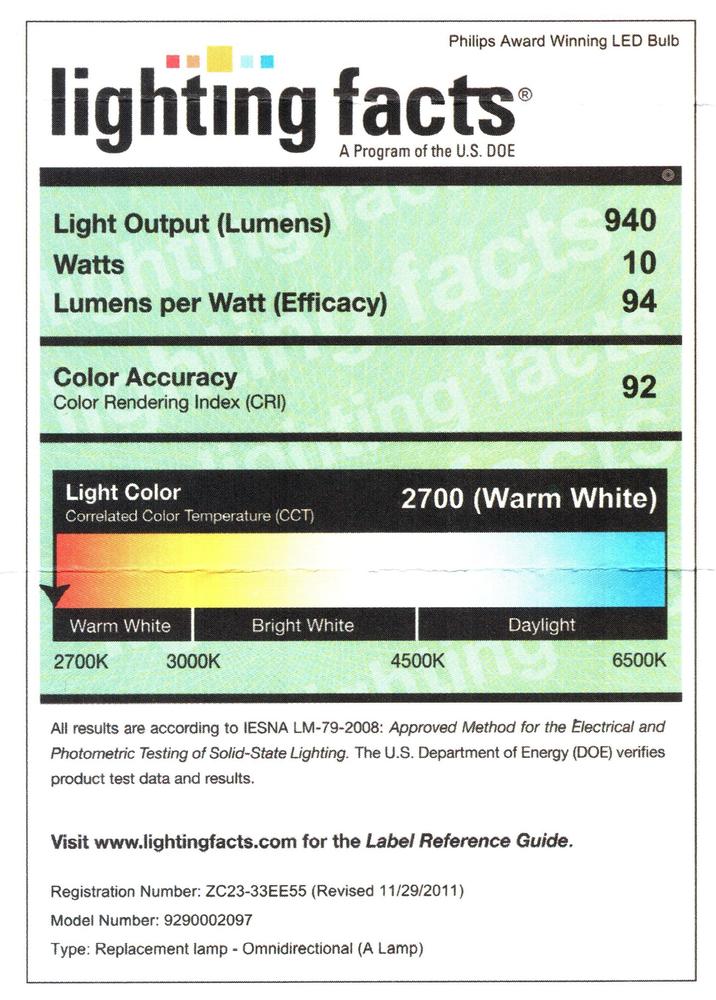

This is actually a simplified version. On the Department of Energy’s LightingFacts.com, they have an example of an LED Lighting Facts label that has all the above information, plus CRI, CCT, efficacy (lumens per watt), registration/model number, and a more detailed color temperature gauge (that’s no longer in black and white). The simplified version has been the official one, in keeping with the look and feel of the FDA’s label that we all know so well, but it’s really just a start. Right now, the DOE mandates that all Lighting Fact labels must include brightness, energy cost, the bulb’s life expectancy, light appearance (for example, warm or cool), energy usage, and whether the bulb contains mercury, on the back of the box. The front must include brightness in lumens and estimated annual energy cost. The rules also state that the lumen output and presence of mercury must be printed directly on the bulb. After March 2012, manufacturers will have the option to also put lumen maintenance (the projected loss of light over time) (Figure 6-4) and warranty information on the label.

One thing that’s not mentioned in the Lighting Facts, but would be helpful to appear on the box (or at least on the manufacturer’s website), is if the bulb is designed to work in an enclosure. Not all LED bulbs are, so you should know what you are getting into before you make your purchase.