CHAPTER 2

What Blend of Management and Leadership Mindsets Is Best?

Management is efficiency in climbing the ladder of success. Leadership determines whether the ladder is leaning against the right wall.

—STEPHEN COVEY

Leadership and management mindsets are two sides of the same organizational coin. When you are operating in the management mindset, your conversations focus on quantitative goals, deadlines, and measureable results. Within the leadership mindset, the conversations focus on the future and how people will grow. Combining both mindsets in appropriate ways and at appropriate times will produce top-notch results in your organization.

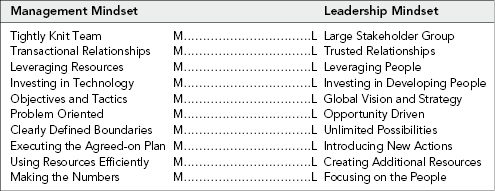

Figure 2.1 contrasts activities typical of executives operating in a management mindset with those typical of a leadership mindset. Most executives regularly toggle between the two mindsets during a business day to produce the results expected of their position. As you climb to positions of higher responsibility, you will find yourself spending an increasingly higher percentage of your time operating in the leadership mindset, yet some activities in the management mindset will still be necessary to achieve your objectives. This chapter will guide you to consciously make the shift more easily and to hold conversations that blend the two mindsets in a mix appropriate to your position and the situation at hand.

FIGURE 2.1. Management and Leadership Mindsets.

Where on each management-leadership continuum do you currently focus? Where should you be focusing?

All of the management and leadership activities listed in Figure 2.1 are essential for success, yet their focus is different. The management mindset focuses on getting things done through others, whereas the leadership mindset considers future possibilities for the organization and its stakeholders and how to build the organization to achieve them. Your leadership mindset defines the objectives; your management mindset ensures that those objectives are met.

We have left the era when management and leadership were separate and unequal positions, when managers could operate in silos and concentrate only on tasks within their responsibility, leaving leaders to ponder the future and look horizontally across the organization. As a high-potential executive in today’s world, you must instead consciously know when and how to shift from one mindset to the other to produce results that satisfy the responsibilities of your hierarchical position.

You need to make this shift whether you are in a business, government agency, nonprofit, educational institution, or the military. Only the specific weighting of each mindset varies depending on the type of organization, its mission, and its values. Regardless of your position, you are not either a leader or a manager—you are both a leader and a manager. You, and everyone around you, must blend the two mindsets appropriately in order to create a high-achieving organization and find the optimum balance between meeting current targets and pursuing future opportunities. The unique blend of the two mindsets that is suitable for your position will strongly influence the conversations you have with your people.

Conversations Make the Difference

Executives use conversations to engage, connect, align, direct, and motivate people—but their results vary widely. For example, consider the conversations, strategies, rallying cries, and results of two well-known leaders who gave voice to inspiring visions: John F. Kennedy, president of the United States from 1960 to 1963, and Dr. Andrew von Eschenbach, director of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) from 2001 to 2006.

After extensive conversations with cabinet members and technical experts, Kennedy felt confident in challenging Congress and the American people: “I believe this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth. No single project in these times will be more impressive to mankind; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

In the months prior to this call to action, Kennedy held conversations with his top advisers and the brightest scientists in the country, who cautioned him that the United States lacked the fuels, the materials, the engineering skills, and the budget for such a gargantuan project. His answer was, “Now we have a list of things to do. Let’s get started! I’ll get the money.” In giving this famous speech, Kennedy met his commitment to obtain funding for the man-on-the-moon project and ignited the imagination of both young and old about future possibilities.

He also appointed Wernher von Braun, who designed German rockets during World War II, to organize what became the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). The organization was deluged with applicants for virtually every position; its pivotal interview question was, “Do you believe we can land a man on the moon and return him safely in this decade?” Any applicant who hesitated in answering yes was dismissed. The conversations focused on how—not if—the goal would be achieved. Based on the clear vision broadcast by Kennedy, the interviews were an effective early use of the management mindset. The NASA team became opportunity driven rather than problem focused.

Dr. von Eschenbach approached his grand vision differently. He had a distinguished career in oncology as president of the American Cancer Society, prior to being appointed in 2001 as NIH-NCI’s director. In 2003, in the “Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2000,” coauthored by the NCI and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, von Eschenbach surprised most NIH-NCI scientists by challenging them to erase the suffering and death caused by cancer—and to do so by the year 2015. He said, “One of every two men and one of every three women during their lifetime will hear the words: ‘You have cancer.’ One American every minute is dying from this disease. It is an old and enormous problem. But I want to talk less about the old problem and more about fresh thinking.”

His vision was vigorously supported by Congress and the American Association for Cancer Research. At the time, NIH-NCI was a thirty-year-old organization with a proud history of success. After receiving the challenge, NCI physicians and scientists, in private conversations among themselves, focused almost exclusively on the difficulty of achieving the goal and on their concern about the false hope it might engender in the public. They wondered why such a proclamation was needed and were alarmed that it might divert resources from ongoing programs. They felt neither a connection with von Eschenbach nor an alignment with his vision.

Effective Conversations Create Alignment

Both leaders promoted a clear vision of the future and set arguably clear long-term goals. Let us consider from several leadership and management perspectives the events that followed and the results that were achieved.

First, the goal Kennedy set, though difficult and challenging, had well-defined success criteria that stimulated creativity and passion. The ensuing conversations focused on building a team to achieve the goal based on the clear vision of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to earth. Further, once that goal was achieved, the technologies and strategies could be applied to exciting future projects. In contrast, the goal von Eschenbach set was open to interpretation. Did he mean no one would ever die of cancer? Did he include all types of cancer? Should people focus their research on cure or prevention? Therefore, conversations among NCI oncologists and scientists questioned whether the goal was achievable, as there were so many strains of cancer, and were concerned that an approach that worked for one cancer might not work with others.

A second pivotal difference was in how the leaders built relationships. Kennedy had the stronger power base on which to build relationships, yet von Eschenbach arguably had a more noble cause. Kennedy’s conversations stimulated focus and enthusiasm in his followers, and he cemented their commitment by delivering on his promise to get money from Congress for NASA. In contrast, von Eschenbach’s conversations were ineffective in dealing with his followers’ doubts and dissention. He left uncomfortable questions unanswered—even basic strategic questions—which caused experienced researchers to fear failure rather than to focus on success.

A third difference had to do with the early decisions made on each project. For example, Kennedy appointed von Braun to lead the mission because of his proven rocketry expertise; von Eschenbach made no analogous appointment. The criteria von Braun used to select NASA employees produced a staff that saw challenge as an exciting adventure rather than as a mountain to climb. Conversely, von Eschenbach did not provide a strategy that was in synch with NCI’s culture and ongoing projects and that would mobilize its extensive expertise and resources toward achieving the new goal.

In the end, of course, the actions these leaders initiated produced very different results. NASA landed men on the moon and returned them safely in 1969, six years after Kennedy’s death in 1963; cancer remains a major health threat to this day. Kennedy blended the leadership and management mindsets effectively to produce an extraordinary result, whereas von Eschenbach and his key people operated primarily in a management mindset. He focused on the goal rather than on motivating people to achieve it. Von Eschenbach’s results are typical of well-meaning high-potential executives who are not effective at blending conversations in the management and leadership mindsets to achieve the desired results.

Your Generation Influences Your Mindset

One challenge facing most organizations in the United States and many abroad is generational mindset biases. The top executives we speak with—most of them from the baby-boom generation—often complain about the work ethics of Generations X, Y, and Z. They are concerned about the inability of older executives to work effectively with high-potential younger employees. (As an indicator of which generational group you are in, ask yourself whether you take a new electronic product out of the box and start using it, or whether you read the instruction manual first. Older generations expect the instructions to be extensive and clear; younger generations feel that if a product needs directions, then it is not well designed.)

The top executives ask the same question of both groups: “What are you thinking—why can’t you connect and align with each other?” Baby boomers describe the younger generations as spending too much time socializing and being creative (the leadership mindset) and not being willing to work hard to get today’s job done (the management mindset). One baby boomer executive bemoaned, “How can they expect to get ahead without paying their dues and learning the fine points of their jobs? They won’t be ready for a promotion until they work the way we always have. They just don’t understand how the system works.” For example, in some high-powered accounting, engineering, and law firms, the younger generations are reluctant to work long hours the way the older executives did to get ahead, and that endangers the business model of using high billing hours from junior associates to support the salaries of seasoned partners.

At the same time, younger workers complain about their bosses’ unwavering focus on getting the job done, about how long it takes to move up the leadership ladder, and about their lack of participation in strategic conversations and decisions. They say heatedly, “At companies like Facebook and Google, my contemporaries are included in strategic conversations, and promotions happen faster than here. I shouldn’t have to wait three years to get promoted just because that’s how long it took my boss and his boss. The world moves faster today—my organization is lagging.”

The two generational groups rarely have productive conversations with each other because they are approaching the discussions from conflicting mindsets. As a high-potential executive, you must bridge these points of view—get each group to look at the issue from the other’s mindset as well as from its own. Previous generations faced this problem too, but it is more intense today because communications across global markets are significantly faster and easier for everyone.

Harnessing Generational Mindset Differences

Unlike baby boomers, today’s high potentials grew up in a connected world saturated with information. Arguably, the younger generations spend more time making connections than completing work. Because the focus on people comes more naturally to them, they tend to be more comfortable operating in the leadership mindset than in a get-it-done management mindset. Conversely, baby boomer executives often have a laserlike focus on producing results and making the numbers. Of course, both mindsets are essential for success, so each group must leave room for the other to express itself. The most ineffective thing either group can do is to demotivate the other by ignoring or minimizing its leadership or management tendencies.

Marcelo, who became a division president in a public company after thirty-plus years with the firm, told us about his experience: “During a meeting, one of my young high potentials—who had been invited to observe the discussion—blurted out an idea during especially tense negotiations with a strategic supplier. At first I was angry because his participation was unexpected and, frankly, unwanted. I felt like firing him. Yet the supplier loved the idea, and it broke the logjam. Later, I realized that his idea was both creative and apropos. It enabled us to complete the negotiations and nail down a win-win long-term contract. I promoted him instead.”

The world Marcelo had grown up in was quite different—concealing information was a way to demonstrate power. Beginning as an apprentice, he copied the methods senior workers used to get ahead, and managed just as his bosses had managed. Creativity was somebody else’s job—someone high up in the company hierarchy. Even though that approach had produced success for Marcelo, the meeting with the strategic supplier changed his thinking: “Now, before every critical meeting with stakeholders, I hold a brainstorming conversation with key executives and high potentials from several areas of the organization. I challenge everyone to leverage one another’s experience and knowledge to come up with the next great idea. This bridges generational gaps and breaks down silos.”

Another complaint we occasionally hear about the younger generations has to do with their strong sense of entitlement. They grew up in a system that awarded trophies for playing a sport rather than for winning a championship. They earned a degree, so the world now owes them a living. This issue, though common, seems to play out more at the individual level than as a true generational trait.

For example, Joyce is an executive who has two adult sons, each of whom is on a different end of the entitlement spectrum. She told us about them: “My husband and I were downsizing, so we asked our sons to take away as much of their childhood things as they could from our old house. One took only two trophies; they were from tournaments where his team was the league champion and he made significant contributions to their victories. He threw away scores of awards that he called ‘showing-up trophies.’ Our other son insisted on keeping every award he had ever received and asked us to continue storing them for him.”

She considers those behaviors when she hires new employees and has conversations with her high potentials. Like Joyce, you must be aware of your generational bias toward either the management or leadership mindset, and harness that bias in your hiring and promotion decisions and in your leadership conversations.