Chapter 6. Leading Enterprise Wide

Leading enterprise wide means fostering and achieving alignment across all levels of the organization through the development of a centralized decision-making framework that clearly states who you are, what you’re after, and how you’re going to get there as an organization. It acts as your “Enterprise True North” by rallying the entire organization around your common purpose: the pursuit of perfection in all you do in the quest for value creation and delivery.

Have you defined your strategic mission (why your company exists), vision (the future state you’re trying to create), and value proposition (proposed value you’re after)? Do the people who follow you understand your vision and how you propose to get there through the execution of your mission?

Without a written, well-thought-out plan, it becomes nearly impossible to mobilize others toward your common goals, known as strategic objectives.

In this chapter, we’ll spend some time discussing how you can build a centralized strategic decision-making framework that ties your mission, vision, and value proposition to your strategic objectives. You can then use the strategic roadmap and release plan to mobilize the Lean enterprise toward the realization of its value proposition. First, though, we’ll discuss the need for aligning all areas of your enterprise, and why that’s at the heart of this element of Lean leadership.

Recognizing the Importance of Enterprise Alignment

A lack of alignment and collaboration has caused a lot of friction within 21st-century companies, as they struggle to redefine their operating models around digital products/services. Over the last ten years, as executives have worked to grasp the impact of how technology has changed the nature of business, how things get done, and how products/services are delivered to the market, shadow technology organizations that report directly to business leaders have arisen. This practice of circumventing in-house technology organizations has become more and more common, as business leaders feel the pressure of disruption and the need to directly control the product development process as a result. Many technology leaders continue to struggle to change and become more responsive to this new, more collaborative way of working. Gone are the days when the technology organization could independently build and deliver products/services with little to no active input from the business. To some, that might sound like radically odd behavior, but the relationship between the business and technology has never been so strained. When you think about how much is spent on digital transformation (over $1.3 trillion in 2018),1 the lack of alignment becomes a major problem. In my opinion, this is the main reason why so many digital transformations fail. An astonishing seven out of eight Forbes 2000 companies that have attempted to transform have failed, per a study recently conducted by the PulsePoint Group.2

No matter what seat you occupy within the business, technology, or operations, enterprise alignment must be a priority for you as a Lean leader. The rapid change that demands flexibility and responsiveness on your part is here to stay. To ensure enterprise alignment is happening, all parts of the Lean enterprise must be on the same page and under the watchful eye of its Lean leaders, who are capable of working together to foster and deliver value to both its customers and company alike. It all begins with having a frank discussion concerning your innovation strategy. What expectations do leaders have for each other when it comes to innovation?

Understanding the Importance of Alignment and Engagement

Lean leaders on both sides of the table—technology and the business—understand that collaborating to get alignment on expectations and strategic direction is one of the simplest ways to ensure both sides understand how bringing in new technologies and new ways of working to address disruption is going to be handled. One CIO I worked with in the past was faced with a dilemma. He had a $40 million budget to provide technology services and support to a $1 billion business division of a major US-based company that wanted to develop cutting-edge robotic capabilities for its customers. The problem: internally, his organization didn’t have the technical savvy to handle the development of both the hardware and software that would ultimately result in an end product delivered to its customer base. Like many internal tech shops over the last ten years, his department had fallen victim to the outsourcing trend of the early-to-mid 2000s, and he just didn’t have the people or the ability to attract the type of developers that could deliver such a complex solution.

Instead of throwing up his hands and giving in, he decided to work with the SVP of the business line to proactively build a vision and strategy that would manage expectations about the product/service expertise he could offer them, as well as how his department could help the business leaders execute on it. This CIO realized he could use his knowledge of the business to act as an internal technical consultant and ensure that a practical and cost-effective solution could be developed, on time and on budget, that delivered the competitive edge the business was looking for. After all, the business leaders had a business to run, and they weren’t technical in nature. By partnering together, these leaders created a win/win situation for both their customers and the company.

He assembled a small team to work with the business leaders to define their high-level product/service requirements. Then he and his staff consulted with and advised the product managers to identify a technical partner that had the expertise to work with them to develop the product. He found a small startup in Silicon Valley and gave them seed money to develop a prototype. Every month, he conducted a site visit to check on the project and the progress the startup was making through its build/measure/learn loop. He also invited the business leaders to accompany him to get a firsthand look at the progress. Together they were slowly building the next generation of this product line for the organization. By engaging the business leaders, the technology leader was able to maintain transparency and visibility as to where the money was going and what progress was being made, which had been a long-standing concern between the two departments, with the business leaders feeling, more times than not, like they were throwing money down a black technology hole.

Moral of the story: smart Lean leaders must insist on enterprise alignment to ensure the survival of their organizations. They must think outside the box as to how to achieve it, as the pace of change continues to intensify, causing global market disruption and fierce competition. The only response is to counter with alignment, agility, creativity, and innovative ways of getting the work done to meet the demands of today’s continuously evolving business climate.

But how do you go about creating alignment inside the Lean enterprise? The best way to start achieving this goal is to think about where you ultimately want to end up.

Starting with the Endgame in Mind

Whenever I engage with a new client, the first question I ask the senior leaders of the organization is, “What are the customer outcomes you expect to achieve by undertaking this effort?” This question is of paramount importance and must be answered in a mindful way to ensure my team and I are achieving the right results for our clients. Having a keen understanding of what you’re after when it comes to your customer is the fastest way to achieving real and meaningful business results, because it crystallizes what you’re after and acts as a guiding theme for you and your organization.

But what are customer outcomes, and how are they developed? A customer outcome is an achievable end state that has measurable results that can be observed and verified from the customer’s perspective. From the Lean enterprise’s perspective, customer outcomes must be described as top-level strategic objectives with actionable initiatives tied to them that can be traced down through the organization and then back up again, as they are achieved through an ongoing measurement process. Only one senior leader is held accountable for creating the desired end state within a given timeframe through the application of a holistic approach that engages the entire organization to achieve the desired outcome.

Take, for example, the New Horizons situation we’ve been discussing. The persona analysis rendered the customer outcome of:

High-quality vehicle service and repair work done accurately and on time, in a professional and respectful way

The team’s analysis unfortunately showed that this outcome was failing to happen more times than could be tolerated by the dealership’s customer base, thus causing customer satisfaction scores to drop through the floor. The problem wasn’t the quality of the product itself, since customers weren’t bringing these well-known, high-quality luxury vehicles in for out-of-the-ordinary service and repair work. The root cause of the issue was the dealership’s way of handling the vehicle servicing, warranty, and repair work. Jim Collins, the owner of the dealership, charged Nancy, the new service manager, with figuring out why both customer satisfaction and retention rates had dropped. He set two outcomes for Nancy, both to be achieved within the next six-month period, based on the persona findings and manufacturer’s reporting:

Decrease the service request error rate by 65%

Increase the NPS by 25 points

These outcomes are both specific and customer-focused, and Jim can easily measure whether Nancy achieves them or not within the given timeframe. I know this all might sound pretty basic, but you’d be surprised to find how many senior leadership teams I’ve worked with only vaguely define the outcomes they’re trying to achieve, in a manner that is neither specific nor measurable. Common outcomes, such as increasing productivity and/or revenue and cutting costs, are often mentioned without an understanding of exactly how to make those things happen or even why they’re important in the first place. I think if you went out and asked many leaders today to define the outcomes they’re seeking, you’d probably see those three in their top ten lists, with little or no direct link back to customer and business outcomes and without understanding the full picture as to how to produce the desired results. Throwing vague or unobtainable outcomes around does little to help or mobilize your workforce in the long run. So let me ask you this: as a Lean leader, have you defined a clear set of outcomes you’re driving toward to mobilize and lead those that follow you?

Building a Centralized Strategic Decision-Making Framework

Strategy is the process of forming common goals that unite people to ensure everyone within your organization is working together toward achieving both customer and business outcomes. It offers a systematic way to determine how your organization’s resources will be used to accomplish these goals, as well as how success will be measured. Without a well-composed strategic framework, there’s no way to determine whether you’re creating and delivering value. The famous saying by Helmuth von Moltke, a general in the Persian army in the 1800s, later paraphrased by Correlli Barnett in 1963—“No plan survives contact with the enemy”3—was about strategy. I’ve modified it some and have often said to my clients and teams that “No plan survives contact with the customer!” However, that doesn’t mean you just throw planning out the window altogether. On the contrary, it means you must be flexible and able to adjust as you interact with your customers within their environment, because you must meet them where they are and on their terms, not yours. Strategic planning is continuous improvement at its best. It’s a continuing process of adjustment and waste removal, and it must be constantly performed to ensure your goals adjust and change to accommodate contact with your customers. Strategy is not a static thing; it must change and evolve to propel the Lean enterprise forward.

Strategy empowers everyone in the organization and reduces the time it takes to make decisions. It pushes decision-making capabilities to the people performing the work at the gemba (place of work). With a framework in place, there’s no more waiting on top executives to make decisions so that work can proceed. On the contrary, informed decisions are made on the ground, in real time, at the point when they’re needed. Laying out and maintaining a well-formulated strategy builds a centralized strategic decision-making (CDSM) framework that can be used within the organization to make decisions in line with a company’s vision, mission, and value proposition. Take, for example, Amazon’s vision and mission statement, which was created over 18 years ago by its founder, Jeff Bezos:

Our vision is to be Earth’s most customer-centric company; to build a place where people can come to find and discover anything they might want to buy online.4

Given that Amazon’s product and service offerings are so vast, it has a suite of value propositions, based on those product and service offerings:

- Kindle

Easy to read on the go

- Prime

Anything you want, quickly delivered

- Marketplace

Sell better, sell more

Plus many other Amazon product/service value propositions, such as Amazon Music’s “Music and More.”5

Bezos’s mission was to build a place where people could find anything they might want to buy online, and his value propositions were convenience, speed, and choice.6 He has publicly stated he believes the company’s success has been greatly influenced by its unwavering commitment to its vision and mission and its relentless pursuit to fulfill its value propositions. He also believes they represent the guiding lights behind his leadership decisions and have greatly contributed to the company’s tremendous success, because everyone at Amazon knows why the company exists, what it wants to become, and the value it attempts to create for its customers. There’s no guessing or uncertainty because Bezos made it very clear from the start. Everyone works together toward achieving a common set of strategic goals, and any decision at any level is made with those goals in mind.

The success of companies like Amazon is a testament to the effectiveness of a proactive strategic planning process and the development and implementation of a strategic framework in general. Have you taken the time to develop these tools of empowerment and accountability for your workforce? Or are you stuck in 20th-century thinking that says managers much be omniscient, omnipotent, and omnipresent? Let me tell you, those days are gone. So let’s roll up our sleeves and get to work on creating your strategic framework.

Understanding the Strategic Planning Process

A CSDM framework gives an organization the ability to define and then socialize all of its important decision-making elements to ensure everyone in the Lean enterprise understands where it’s headed, how it’s going to get there, and what value it intends to create for both its customer and the company. Its purpose is to empower everyone in the organization to not only do the right things but do them for the right reasons as well.

Building your framework requires all parts of the organization to participate in the strategic planning process. It’s not something that’s handed down from the executives (the proverbial “mountaintop”) and then precisely executed by the masses. It’s a plan that must work in the trenches, where it will be adjusted “on the fly” by an empowered workforce that’s in direct contact with your customers. These workers must understand the guardrails within which they can operate to satisfy customers and create a differentiated experience. Informed decision making is what your strategic framework and planning process is after, not precise execution. A well-developed framework grows and changes as everyone in the organization gains more and more knowledge about your customers.

This framework must also embrace nimbleness and agility in the sense that it must be adaptive and designed so that you can quickly respond to both internal and external opportunities and threats. It’s not a one-and-done activity or something that’s written in stone. It’s usually constructed to span at least a 12-month period. Going out any farther than that is a waste of your valuable time and energy because things are changing so rapidly. Also, keep in mind that you must revisit it every quarter to ensure its direction and destination remains relevant to the overall goals and objectives of the organization, as well as updating it for the next quarter’s work to ensure you have a 12-month rolling plan at all times.

If a change occurs and a course correction becomes necessary, you must have the courage to make the tough decisions to ensure the company is still creating value through the opportunities it chooses to develop. It doesn’t do anyone any good to continue down an outdated or obsolete road just because it was once thought to be the right direction. The world is changing so rapidly that building a strategic framework and then periodically examining and adjusting it must become part of a healthy strategic planning process to remain competitive.

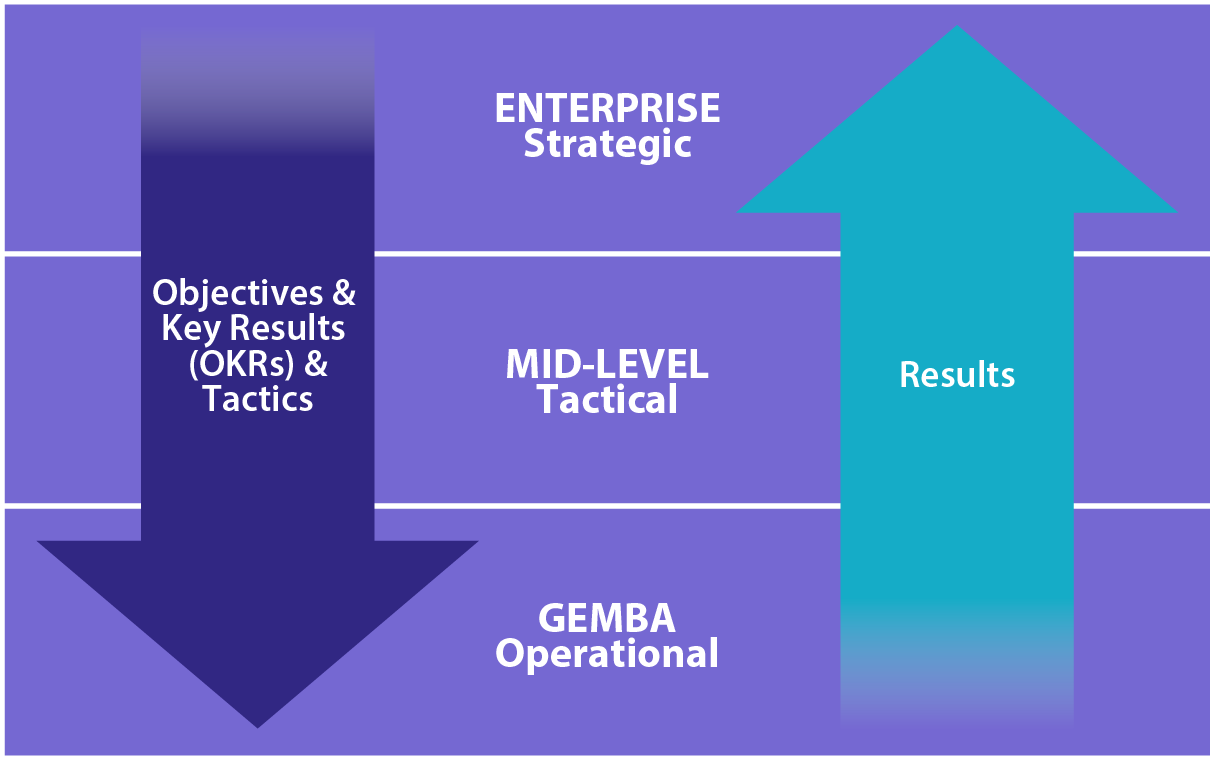

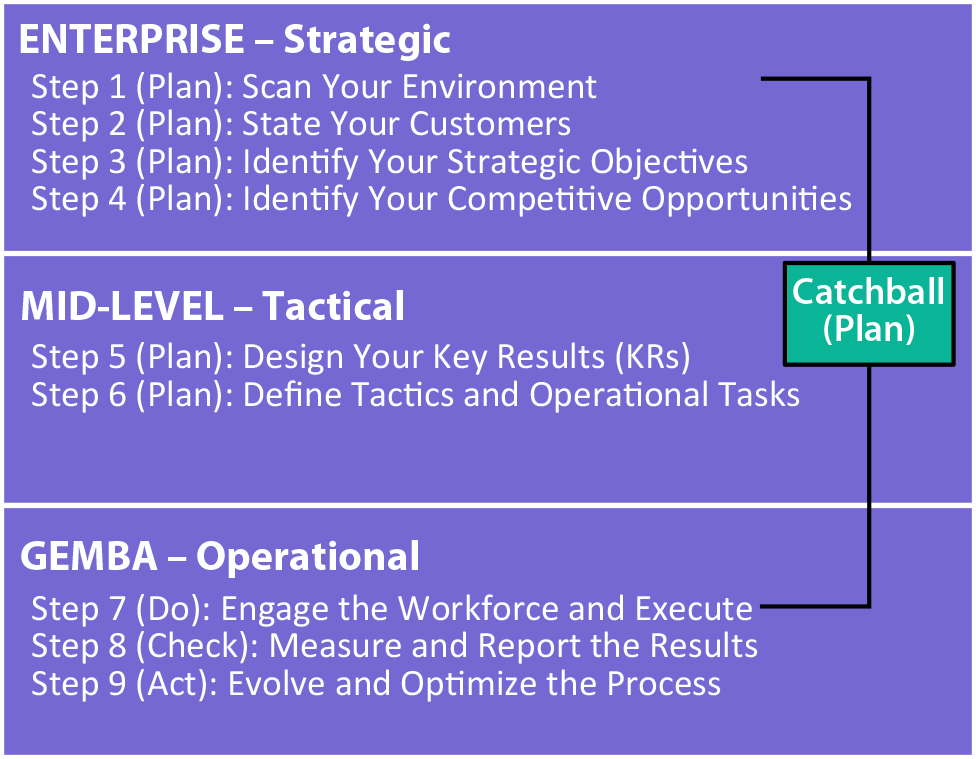

To build a viable framework, you must focus on all the layers of the Lean enterprise, as depicted in Figure 6-1.

Figure 6-1. The strategic planning cycle

Strategic direction must flow from the senior leadership team to tactical middle management and through to the operational level at the gemba. Then, as results are achieved, they must flow back up through the enterprise to report progress against plan and to make sure any course corrections or changes in strategy are also known to senior leaders, to keep them informed as they continue the planning cycle. This cycle repeats itself over and over again, allowing Lean leaders to learn and adjust from the feedback they receive, continuously honing and improving upon the strategic elements throughout the life of the organization. Overall, the CSDM framework consists of the following components:

Strategic planning canvas

Mission, vision, and value proposition

Strategic objectives

Competitive opportunities

Key results (KRs), tactical plans, and operational tasks

Investment strategy

Strategic roadmap

MVP release plan

Let’s look at the practical steps for creating your strategic planning canvas.

Nine Steps to Creating Your Strategic Planning Canvas

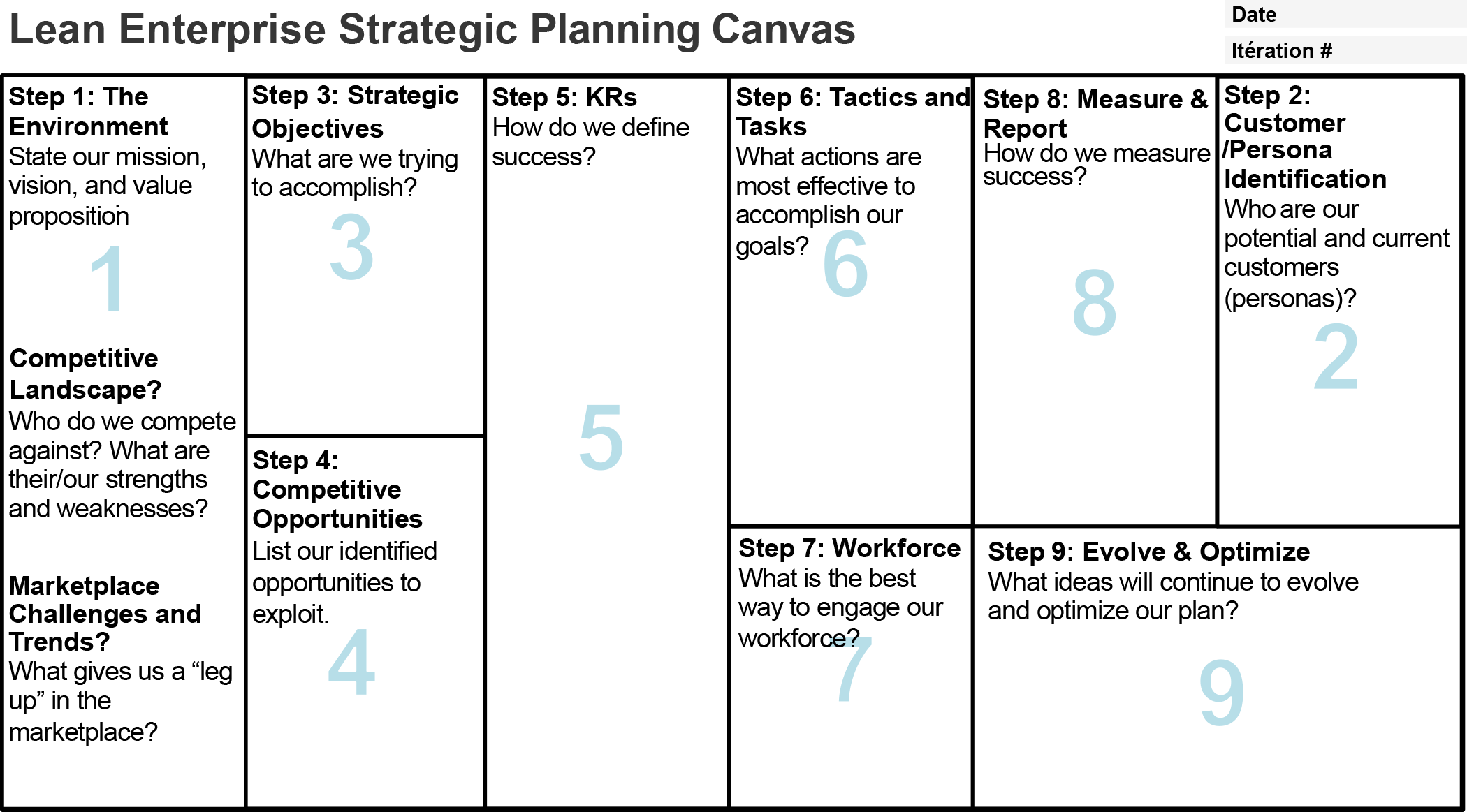

The strategic planning canvas is the first of four tools used to create your CSDM framework. Its purpose is to help you clearly define your:

Vision, mission, and value proposition to ensure you have a clear picture of what you want to become in the future, how you’re going to get there, and the value you want to create as a result of this process

Strategic objectives that are the overarching goals and objectives you want to achieve that fulfill your vision

Competitive opportunities that give you a leg up on your competition if achieved, and that are tied to your strategic objectives

Objectives and key results (OKRs) so that you can quantifiably measure progress and make adjustments if necessary

Tactical plans and operational tasks that must be performed to complete the work on your opportunities

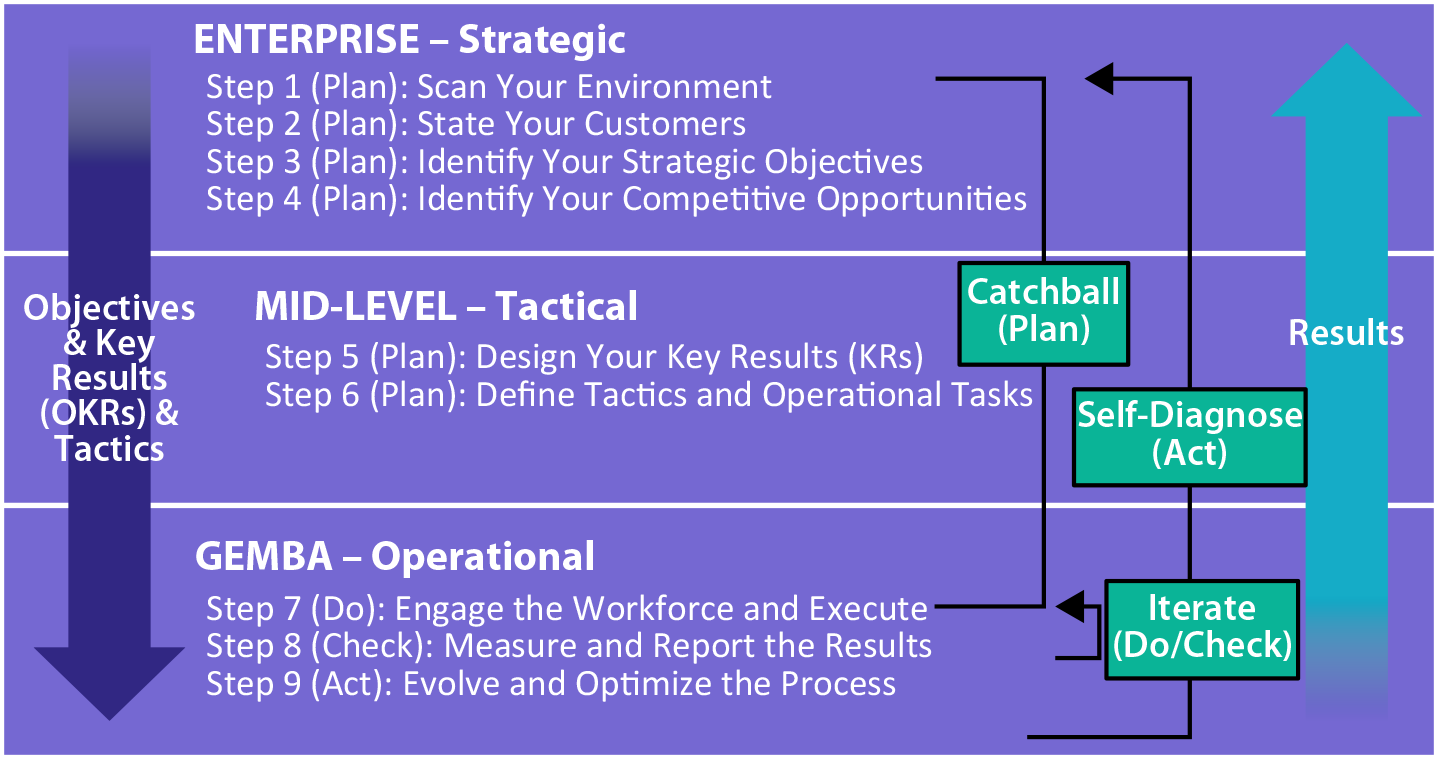

Building your strategic planning canvas is a nine-step process, as depicted in Figure 6-2. It’s based on the Lean Plan/Do/Check/Act (PDCA) cycle to ensure it continuously evolves, allowing the Lean enterprise to remain relevant and competitive.

Figure 6-2. The strategic planning canvas process

The first four steps are performed by senior leaders at the enterprise level, which encompasses the first part of the Plan phase. Understanding your environment and customers and then identifying your strategic objectives and competitive opportunities both happen at this level. Once complete, this information is passed down to the mid-level tactical managers to complete the Plan phase, by identifying your key results (KRs) and building the tactical plans and operational tasks necessary to achieve them. All of this information is then passed down to the gemba level, where the work is performed for execution, measurement, and reporting. Optimization of the whole process occurs as feedback is pushed back up to the enterprise level, which triggers the whole process to begin again, allowing the organization to constantly evolve in a natural, well-organized way. It’s an infinite loop within the Lean enterprise. The strategic planning canvas depicted in Figure 6-3 is the tool used to document this planning process. It acts as a visual aid to assist in documenting your findings as you move through the nine steps.

Figure 6-3. Lean enterprise strategic planning canvas

Step 1 (Plan): Scan your environment

The first and most important step is to thoroughly understand the environment that you exist and operate within. Building the picture of who you are, what you do and provide, who you compete against, and how your environment operates within the context of your mission, vision, and value proposition provides a clear picture of the environmental factors you’re facing and must address.

Creating/revisiting your mission, vision, and value proposition generates alignment across the entire Lean enterprise, acting as a communication tool to help everyone understand what it’s about, where it wants to go, and what value it will deliver to its customers and for the company.

Analyzing the competitive landscape by researching and identifying how your competitors are working to satisfy your customers’ wants, needs, and/or desires builds an understanding of how you could serve them better through differentiation.

Evaluating marketplace challenges and trends helps you to identify distinct advantages your company possesses that give you a competitive “leg up” in your marketplace.

Crafting your vision and mission statements for your organization is not an easy endeavor. What you’re after is a one- or two-sentence paragraph that provides a concrete way for stakeholders and employees to easily understand why your company exists and what aspirations and guiding principles you have for your business. For example, New Horizons has a very simple vision of “Dedicated to customers and driven by excellence.” Its mission statement is just as simple: “To become the world’s most renowned center for customer service in the automotive sector.” Simple, directional, aspirational, and inspiring are the qualities you’re looking for in well-crafted vision and mission statements.

As for the dealership’s value proposition, it’s just as simple and consists of “Easy to buy and obtain service.” When you look at the value it’s trying to create, the issue becomes clear with the problem in the service department. Overall, the dealership’s behavior is way off base and inconsistent with all three, which has created a sense of urgency to fix these problems. The dealership is not living up to its vision and mission statements, and it sure isn’t creating value for its service department customers.

As far as competition, the dealership doesn’t have any, since it’s the only one within a 150-mile radius. However, another luxury vehicle brand is building a new dealership in the next town over, but that’s at least 25 miles away from New Horizons. Jim and his team don’t think this turn of events poses an immediate threat, since there is a significant difference as far as distance goes, not to mention his location is much more convenient, being right in the center of town.

Step 2: State your customers

The strategic planning process is all about satisfying your customers’ unmet wants, needs, and/or desires in a better way than your competition to ensure you create and maintain a competitive advantage that keeps you at least one step ahead of them. This is the point at which you bring your customer personas into the process by clearly stating who they are, based on your previous persona identification work. If you haven’t identified who your potential and current customers are, now is the time to go back and perform this work. Personas are a crucial element in the process, since everything you do must be grounded in creating and generating value for your customers and stakeholders.

During the CXJM activity performed by the New Horizons TBP team, the following seven personas were identified:

Luxury sedan owner

Sports coupe owner

SUV owner

Truck owner

Van owner

Employee

Community

The next step is to apply these personas when developing your strategic objectives.

Step 3: Identify your strategic objectives

Everything that happens in the Lean enterprise should tie back to what you’re trying to accomplish—everything else is waste. To build a plan that delivers value, you must start with your ultimate goals in mind. By first identifying the customer, business, and stakeholder outcomes you’re trying to achieve, you can work backward to mobilize your organization to produce tangible results for all those involved. Then, by translating those outcomes into strategic objectives that can be broken down into opportunities and executed at both a tactical and operational level, the Lean leader puts a system in place that allows the organization to achieve its goal of creating and delivering value. That’s what the Lean enterprise is all about!

But what exactly are strategic objectives? They’re the main high-level business objectives that form the basis of the organization’s business strategy.7 When developing objectives, it’s important to remember they represent the strategic results an organization is seeking to achieve, based on its value proposition. If a purposed product/service idea doesn’t tie back to at least one strategic objective, then inherently it’s not a strategic fit and should not be considered for funding. Investing in nonstrategic ideas creates waste, and very little value, if any, drops to the bottom line. The strategic objectives must be deeply rooted in and supported by both the company’s vision and and its mission so that everyone understands the journey and can help with charting the course, as well as contributing to their achievement.

Strategic objectives exist at the enterprise level. They represent three to five enterprise-wide “big bets” that a Lean enterprise is trying to accomplish to fulfill its mission and turn its vision into reality. Their purpose is to help organize or group related business initiatives into categories that measure that organizational effectiveness of delivering on your business results. To create them, you must:

Evaluate your product/service quality and value creation and delivery, identifying your strengths and areas that need improvement

Conduct brainstorming sessions to identify desired customer and business outcomes from your strengths and development areas

Roll the results up into categories to form three to five strategic objectives you will work on over the next year

Remember, your vision, mission, and value proposition frame the discussion around the development of strategic objectives as you determine the top three to five enterprise-wide ones that will be used to make decisions between competing priorities and to determine strategic fit for investment allocation purposes. They act as a yardstick to measure progress toward creating and delivering value. They can also be thought of as guardrails to ensure leaders stay on course and don’t veer off into uncharted, non-value-adding side trips.

According to a 2016 Price Waterhouse Cooper CEO innovation survey, innovation leaders that follow an intentional process forecast two to three times higher growth outlooks than those who don’t, predicting a growth curve of over 62% (versus the global average of 35%) within the next five years.8 So unless you put some thought behind what moves the needle, there’s no way you’ll ever be able to measure whether you’re truly succeeding at value creation and delivery.

Returning to New Horizons again, Jim and his leadership team worked to identify the following four strategic objectives for the dealership:

Increase quarter-over-quarter sales

Increase our quality of service to our customers

Increase the use of technology to effectively run our business

Modernize our facilities

Keep in mind these are overall objectives that apply across the entire dealership and not just the service department, since they are set at the enterprise level.

Step 4 (Plan): Identify competitive opportunities

Competitive opportunities are the things you want to become better at in order to generate increased competitive advantage and accomplish your strategic objectives. A great place to look for these is in the Improvement Ideas section of your customer experience journey (CXJ) maps that you developed, after identifying your personas. Understanding how to appeal to your different segments allows you to differentiate yourself in their eyes, as well as strengthen the areas in which the market considers you to be weak. In the case of New Horizons, when the TBP team documented the sports coupe owner persona, they identified the following opportunities (a few of which can be combined to come up with a final list):

Develop a service and repair mobile app

Schedule an appointment capability

Provide arranging for a loaner car capability

Send repair progress notifications

Provide viewable bill capability

Push out a feedback survey

Offer coupons/discounts on next visit

Provide push notifications when next service is due

Provide training to the service staff

Upgrade the loaner car program system

Do random service customer follow-up calls

Perform lapsed service customer follow-up inquiries

After identifying your opportunities, you must tie them back to your strategic objectives to ensure there’s a strategic fit and to prioritize them so that you don’t waste resources on efforts that don’t add customer or company value. For the service journey, the tie back to the dealership’s strategic initiatives are prioritized in the following way:

Increase quarter-over-quarter sales

Perform telephone customer inquiries on lapsed service

Increase the quality of our service to our customers

Provide training to the service staff

Develop a service and repair mobile app

Do random service follow-up customer calls

Increase the use of technology to run our business

Upgrade the rental car system

Now that you’ve identified your strategic objectives and competitive opportunities, it’s time to identify your key results (KRs).

Step 5 (Plan): Design your key results

KRs provide a way of tracking progress made toward accomplishing your objectives and creating additional competitive advantage through completing your opportunities, represented by critical customer, business, and stakeholder outcomes that drive both activities and behavior within the Lean enterprise. Lean leaders use KRs at multiple levels to evaluate their success at reaching their targets. High-level KRs focus on the overall performance of the business through the progress made toward your strategic objectives, while mid- and lower-level KRs focus on progress made on accomplishing your competitive opportunities through acheiving your tactical plans and operational tasks.

KRs also have a considerable ability to drive behavior, so choose them very carefully. It’s essential to think through whether the KRs you select and focus on will drive the desired behavior and outcomes that you expect, without any unintended side effects. For example, focusing on productivity to keep the line running but ending up with large stockpiles of inventory is counterproductive. Keep in mind the rule of cause and effect relationship when setting your KRs. You must be vigilant and guard against creating any undesired consequences.

When writing KRs, keep in mind they must be concise, clear, and relevant, as well as measurable, from both a quantifiable and a qualifiable perspective. That is, each KR must meet the SMART criteria:

- Specific

Is it objective?

- Measurable

Are you capable of measuring progress?

- Attainable

Is it realistic?

- Relevant

Is it relevant enough to the organization?

- Time-bound

What is the timeframe for achieving it?

Taking the strategic objectives developed in step 3, Jim and his leadership team developed the following set of KRs, at the tactical level, for the New Horizons service department:

Increase quarter-over-quarter sales by 5%, for a cumulative total of 20% within the next 12 months

Increase service department sales by 2% per quarter by implementing a service follow-up program

Increase service department sales by 3% per quarter by implementing a lapsed service inquiry program

Increase the quality of our service to our customers within the next 6 months by:

Decreasing the service request error rate by 65%

Increasing the net promoter score by 25%

Increase the use of technology to effectively run the business by:

Launching the first release of the service and repair mobile app by the end of Q1 and the second by Q2

Performing an upgrade to the loaner car program system by the end of Q4

Modernize our facilities

Step 6 (Plan): Define tactics and operational tasks

Tactics are management plans developed to determine how the levels will accomplish the identified opportunities. They can be thought of as tactical plans, such as project plans or to-do lists that identify the discrete steps or operational tasks required to achieve the completion of the opportunity, which is usually time-boxed within a 12-month period. While it’s the responsibility of enterprise leaders to lead strategic planning efforts, it’s the managers and employees who will ultimately be responsible for executing on it. So involving them in the process is crucial, to ensure they’re able to provide input as a means of becoming more invested in achieving the end result. At a departmental level, tactical managers evaluate the opportunities identified by enterprise leaders and then develop tactical plans and operational tasks that will best achieve the desired results.

An important aspect of this process is known as “catchball” (see Figure 6-4), which is an exchange of ideas when developing tactics. The exchange occurs between the organizational levels as they toss ideas back and forth among the leaders within a given level or up and down between levels, returning the “ball” with their input and ideas to the originating level. This process repeats itself as many times as necessary to reach consensus between and within leadership levels. In the Lean enterprise, it’s a way of working collaboratively to identify tactical plans or implement/modify operational tasks that achieve the enterprise’s strategic objectives through the completion of identified opportunities. It’s a participative process that uses iterative planning sessions to field questions, clarify priorities, build consensus, achieve alignment, and ensure that the strategic objectives, competitive opportunities, and KRs are well understood, realistic, and sufficient to achieve the organization’s objectives.

Figure 6-4. Active levels in catchball

In a typical catchball series, the identified opportunity is tossed around by enterprise leadership first. Then it’s tossed down to the mid-level tactical management layer, where they repeat the process amongst themselves or toss it back up to senior leaders or down to their team leaders and so on, until the tactical plans and operational tasks have been cascaded, vetted, and adjusted (both across and up and down throughout the organization). In the end, everyone has contributed at all levels, and clear tactics and operational tasks have been identified and created with everyone’s involvement. This is a much more collaborative and inclusive approach, instead of having enterprise-level leaders throw objectives down from the top layer, expecting the organization to execute things they have little to no input or understanding about.

Finally, keep in mind that tactics and operational tasks are subject to change throughout this process, which means flexibility and adaptability are important characteristics to allow the process to effectively render the desired results. Holding regular progress reviews at least once a month, depending on the volume of changes occurring to the plan, is a helpful activity to manage the change aspects. During each review, results are evaluated, and the tactical plans and operational tasks could need recalibration, followed by another round of catchball.

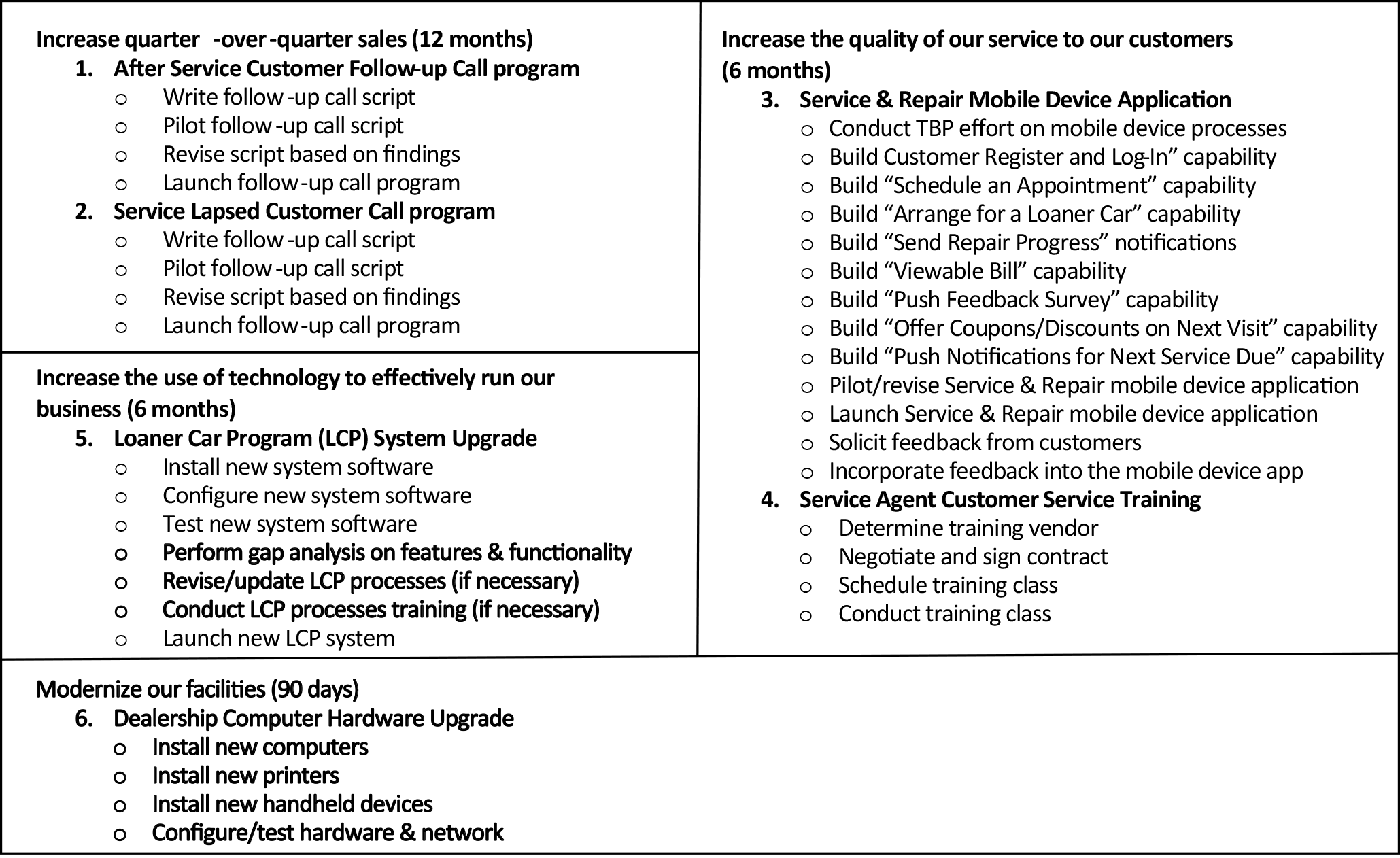

In Chapter 4, “Leading Others,” the kaizen team at New Horizons enabled a rather lengthy game of catchball, as it used the Toyota Business Practices (TBP) method to work through the issues with the Service Request Intake process. TBP is just one of the methods that can be used to put together the tactical plan and operational tasks required to achieve the completion of the opportunity. Others include both traditional and Agile project management methods. The types of plans are identified and listed below for each opportunity.

After service customer follow-up call program: traditional (waterfall) project management plan, combined with TBP/process improvement methods

Service lapsed customer call program: traditional (waterfall) project management plan, combined with TBP/process improvement methods

Service and repair mobile app plan: Agile/Scrum project management plan, combined with TBP/process improvement methods

Service staff training plan: traditional (waterfall) project management plan

Loaner car program system upgrade: Agile/Scrum project management plan

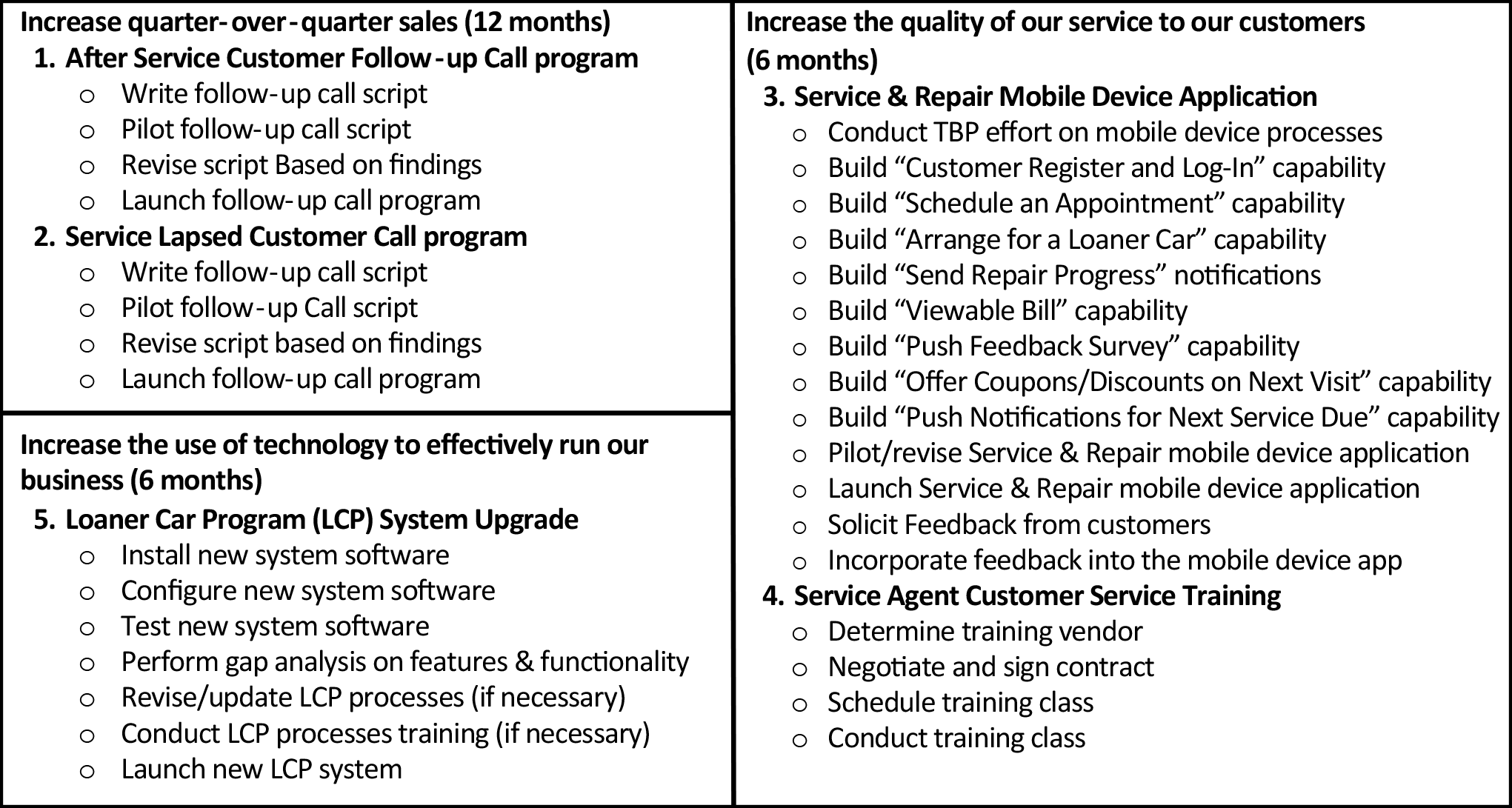

As you can see, one method will not fit every type of opportunity. At the beginning of step 6, the team should discuss which method is best suited for achieving the desired results. The service department tactical plans developed by New Horizons are depicted in Figure 6-5.

Figure 6-5. New Horizons service department tactical plans

Step 7 (Do): Engage the workforce to execute the strategy

Team leaders and members work out the operational details or tasks needed to implement the tactical plans laid out by the mid-level tactical managers. This is the phase in which objectives and plans are transformed into results. That means tactical managers must stay closely connected to the activity happening at this level. They must regularly practice genchi genbutsu, or “management by walking around,” to stay close to the work.

Going back to our New Horizons canvas, the team identified which department will be accountable for the tactical plans and operational tasks for the following opportunities:

#1: Service department and technology

#2: Service department and outside customer service firm

#3: Loaner car program and technology

#4: Service department

#5: Service department

By specifically naming the departments within the organization, the leaders and teams become responsible and accountable for the results they achieve as they work to complete the opportunities that accomplish the strategic objectives determined at the enterprise layer.

Step 8 (Check): Measure and report the results

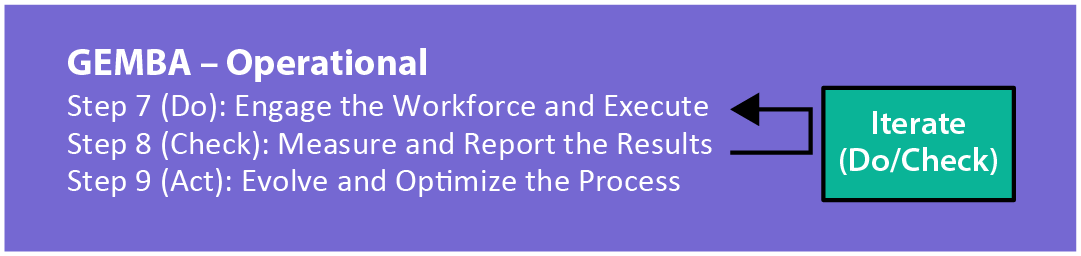

Measuring results is a must in the Lean enterprise. Establishing measurements and then employing the rigor to measure, analyze, learn, and finally adjust is at the heart of the iterative cycle that exists at the gemba (Figure 6-6). The measurements established and collected at this level feed up to the KRs established in step 5 and which contribute to the success or failure of the strategic objectives.

Figure 6-6. The gemba Do/Check iterative process

As you analyze the results at the end of each measurement period, course corrections and adjustments are inevitable. The ability to change your mind and alter your course is built into Lean methods through the continuous learning cycle that is inherently present. And remember, you perform strategic planning to empower your workforce so that they can make effective decisions at the gemba without having to go find a mid-level or senior leader to help them solve the problem, because they know where the company is headed and why it picked that direction in the first place. So as you iterate through your tactical plan, expect it to change and grow as more and more data becomes available. Plan your work, and then work your plan!

The measurement and reporting frequency will depend on the KRs being tracked, which can happen on a daily, weekly, monthly, or quarterly basis. These progress checkpoints provide an opportunity for adjustment of your tactics and their associated operational details. KRs aren’t static. They always need to evolve and be updated or changed as needed. If you’re setting and forgetting your KRs, you risk chasing objectives that are no longer relevant to your business. Make a habit of regularly checking in, not just to see how you’re performing against your KRs but to see which KRs need to be changed or scrapped completely.

Going back to New Horizons, the team determined that KR measurements will be compiled by the data analytics group and posted in the TBP team war room on the fifth day of each month, by strategic objective and based on a frequency that adheres to the following schedule:

#1: Sales-quarterly

#2: Biweekly

#3: Monthly

#4: Monthly

Stating how and when results will be measured sets realistic expectations and determines the planning and adjustment cycles necessary to take corrective action, if needed. Posting the results in a public place makes them visible and lends itself to transparency, ensuring everyone understands the progress being made and the adjustments being taken in the pursuit of the Lean enterprise’s strategic objectives.

Step 9 (Act): Evolve and optimize the process

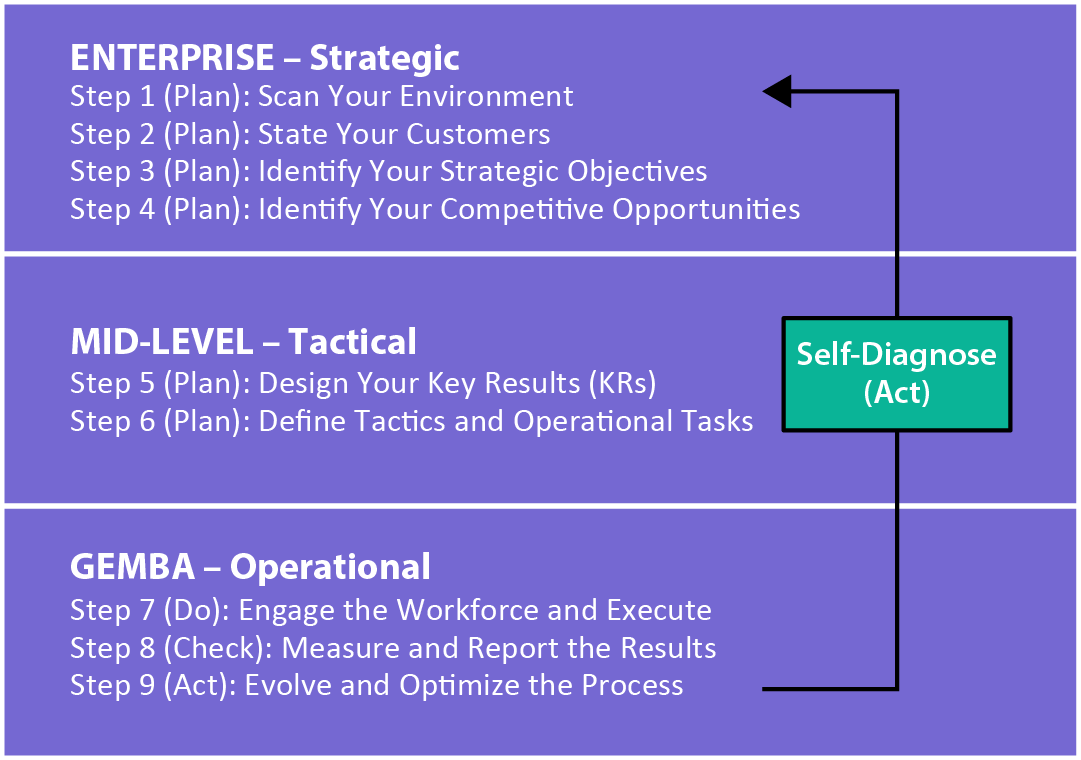

You must understand both the progress and the results being made at each level and account for adjustments and changes in direction being made at the lower levels. The Act phase of the PDCA cycle (Figure 6-7) allows the Lean enterprise to become both self-diagnosing and self-correcting, relying on both the downward and upward flow of information to create a closed-loop system that enables the learning, control, and adjustment (or in other words, continuous improvement) of the entire strategic planning process.

Figure 6-7. The self-diagnosis loop

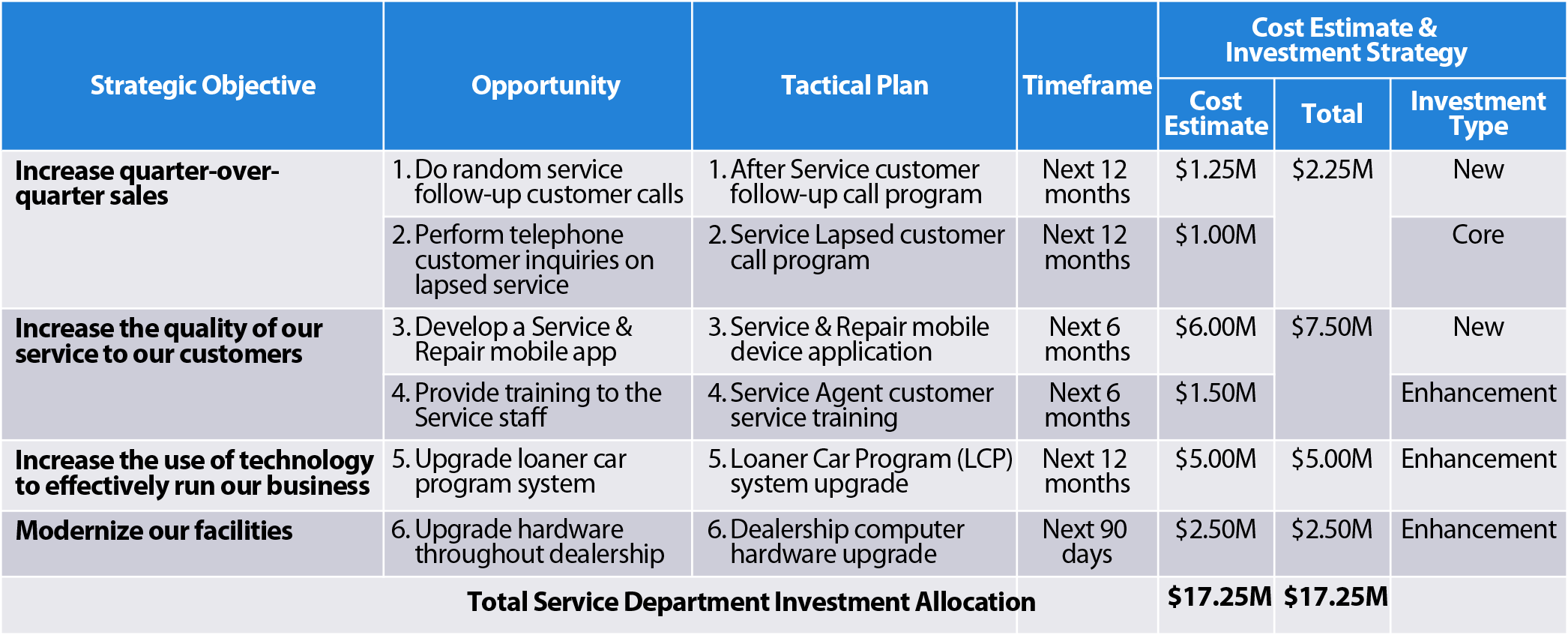

Progress made toward your competitive opportunities and tactical plans, as well as overall direction set by your strategic objectives, must be continuously tracked and formally reviewed on a regular cadence at all levels. Take, for example, the work being done at New Horizons. As the loaner car program team started work on the upgrade of the system, they realized the established processes for the flow of work also needed an overhaul. The new system’s features and functionality had changed significantly since the last release, which is now driving the need to update both the processes and the training as well.

This work represents additional effort that must be added to the strategic planning canvas and traced back to the strategic objective that’s driving the work being done—that is, opportunity #3, “Upgrade loaner car program system,” under the strategic objective of “Increase the use of technology to effectively run our business.” Because the hardware is outdated throughout the dealership, not just in the service department, it will need upgrading as well, which ties back to the same objective (#3) and opportunity (#3). Finally, a new tactical plan, #6, “Dealership computer hardware upgrade” (denoted in bold in Figure 6-8), was developed and added to the canvas. As you can see, a change that originates at the team level must be tracked back up through the levels to ensure the strategic fit is maintained.

Figure 6-8. New Horizons service department tactical plans (revised)

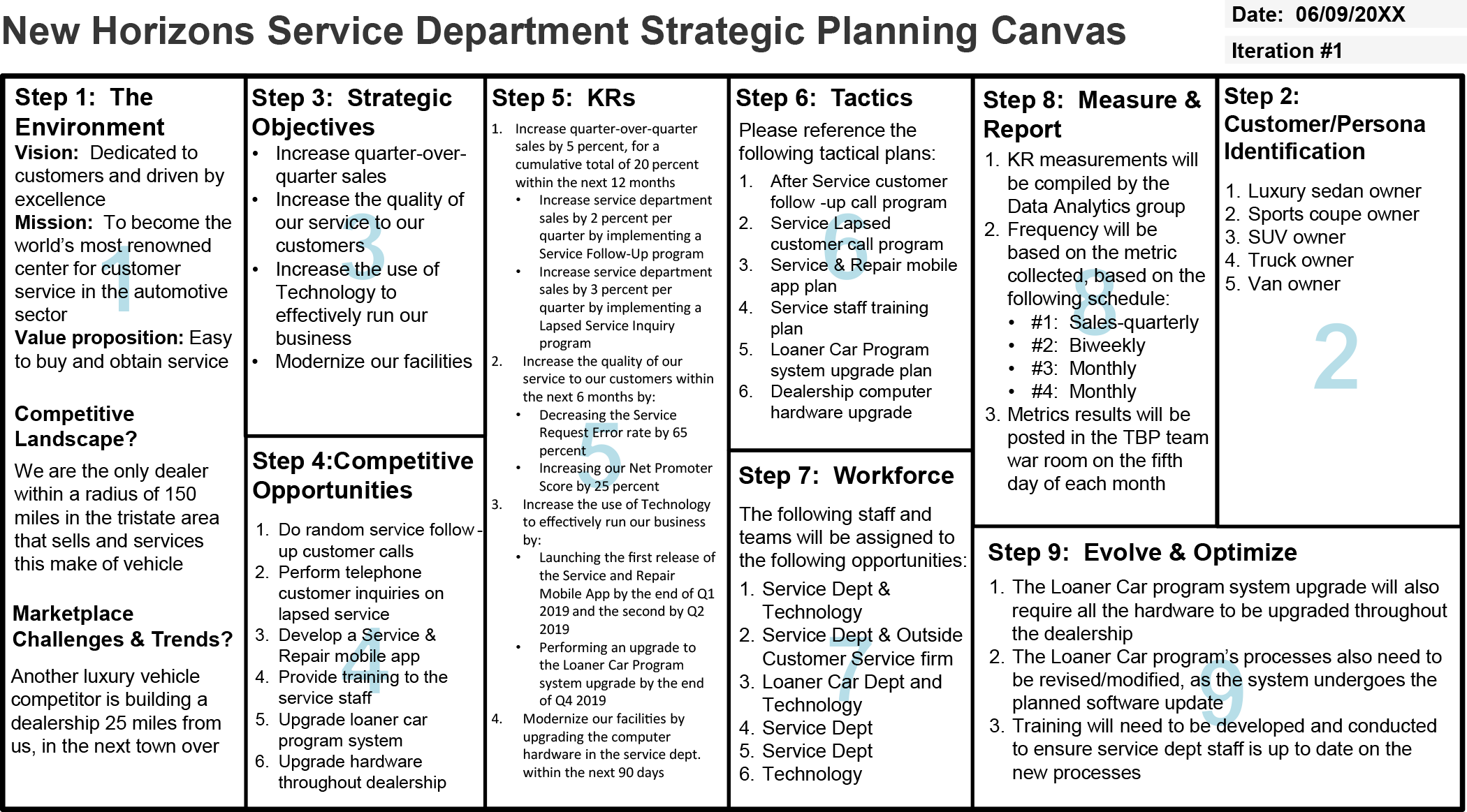

The New Horizons Strategic Planning Canvas

Figure 6-9 shows the completed New Horizons Service Department strategic planning canvas. Keep in mind that it represents the strategic canvas for a single department within the dealership. Completing it is a major achievement for the organization because it represents “the plan” that is now in place for the next 12 months. Of course, it will need to be periodically refreshed and updated as the tactical plans and operational tasks are executed.

Figure 6-9. New Horizons service department strategic planning canvas (large format version)

Now that the team has completed their canvas, they must turn their attention to developing their investment strategy and building and finalizing the dealership’s service department strategic roadmap and release plan.

Creating Your Investment Strategy

Lean leaders must prudently decide, on an ongoing basis, just how much money they need to run, grow, and innovate on their business strategy and then set investment targets based on their strategic objectives and competitive opportunities, developed during the strategic planning process. These targets then drive the investment in intentional (core and enhancements to products/services) and emergent (new or transformational) innovation, based on their strategic objectives, which measures the effectiveness of an organization’s investment strategy. Overall, the purpose of developing your investment strategy is to define how you will allocate your scarce resources (time, money, and people) toward developing new product/service ideas, as well as maintaining and enhancing existing ones. It’s tied to the Lean enterprise’s business strategy and heavily focused on its value proposition through the identification of unmet customer wants, needs, and/or desires, as well as how well the organization delivers customer, company, and stakeholder value.

A well-developed investment strategy is used to:

Determine how much of an organization’s resources are spent on identifying and researching unmet customer wants, needs, desires, target markets, and new product/service ideas

Make investment and trade-off decisions between core, enhancements, and new product/service priorities at the enterprise level

Drive the amount of development effort dedicated to bringing new and enhanced products/services to market at the mid and gemba levels

Determine the size and number of teams and what they work on at the gemba level

However, building the capacity to innovate is not easy, and it’s no longer a choice—it’s a necessity. Maintaining competitive advantage, once an innovative product/service is released, must also be considered. Success breeds imitation, and lots of it.

Developing a Successful Investment Strategy: Apple Disrupts Sony

The Sony Walkman, released in 1979, was a portable cassette player that ushered in the age of mobility and created the mobile personal devices market. An example of disruption at its best, it allowed people on the go the option to listen either to their favorite radio station or to music recorded on cassette tape while running, walking, commuting, etc. The only option up until that point had been the portable transistor radio, which received only AM/FM radio station signals. As the mobile personal devices market grew, more competitors entered the space. Sony continued to maintain its market leader position by evolving its product line, as the types of storage media changed from cassette tape to compact disc (CD) in the late 1990s, by introducing a CD version with anti-skip technology that allowed the company to maintain its competitive edge.

However, the drawbacks to the device, such as short battery life, heaviness, and size, all contributed to its downfall when Apple introduced the iPod in 2001.9 The iPod was lightweight, had a rechargeable built-in battery, and was connected to the Macintosh iTunes platform, where users could download music directly into the device’s memory in the new MP3 format. Sony, once a disruptor, had become disrupted in a market it had created. Apple had listened to the unmet wants, needs, and/or desires of customers and created something that represented even more value that they were willing to pay for. Sony did release its version of a portable MP3 player to compete with Apple; however, Sony never attained the level of success with this product that it did with the Walkman back in the 1980s.

Apple closely tied its strategic framework to its investment strategy. Even back in 2001, Apple understood the power of connecting its products and services together to create and maintain competitive advantage. The iPod leveraged iTunes, an online music-downloading platform, initially accessible only through a Macintosh computer. By doing so, Apple also disrupted the music industry (which Sony also had a stake in due to its 1987 acquisition of Columbia Broadcasting System [CBS] Records, later renamed Sony Music10), killing the vinyl record business in the process. If you aren’t innovating, you can bet someone else is and will eventually come along and disrupt you.

A well-thought-out investment strategy helps companies determine how much they want to spend upfront on their current product/service lines, as well as what they’re willing to spend on innovating new ones. For example, at Google, 70% of investment funding is allocated to core products/services, 20% to enhancements, and 10% to emerging or new product/service innovation.11 By clearly stating the target allocations for each category, Google effectively allocates its scarce resources and eliminates competing priorities by setting targets for both intentional (core and enhancements) and emergent (new) innovation. When an organization goes about setting allocation targets, the goal is to minimize risk while achieving the highest possible return on investment (ROI).

Factors to Consider When Setting Your Targets

Three factors exist when setting your targets:

Industry

Competitive advantage

Maturity level

Depending on the industry, investment strategies will vary. Take, for example, the airline industry. Its allocation targets represent a 60/30/10 split,12 while technology companies represent a 45/40/15 split, and consumer packaged goods represent a 80/18/2 ratio.13 Each industry is unique due to the nature of its business and operating model. It might cost a little less to develop software compared to the cost of developing airline products/services. Technology companies that are labor versus product (airplanes) intensive must set their investment targets accordingly, because it costs about the same to maintain their core products/services as it does to enhance them.

Competitive advantage is the second factor. Whether a company is considered a leader or a lagger affects its investment strategy. Companies that have allowed their competitive advantage to erode find themselves at a disadvantage and often need to play catch-up to market leaders. For example, to increase its competitive advantage and gain a greater share of its market, a consumer packaged goods company temporarily adjusted its investment strategy from a 75/20/5 target allocation to a 50/25/25 split to develop a new product line that increased its market share and gained back its competitive advantage. The trick here is not to sacrifice one for the other in the long run. Changing your strategy must be grounded in facts and not be done merely for the sake of accommodating someone’s pet project. Vetting a new product/service idea takes place at the enterprise level, with senior leaders making the crucial investment allocation decisions.

Maturity, the last factor, is important from the perspective that older, more established organizations have core and adjacent products/services that they must maintain and expand to stay in business. Making big bets on breakout or disruptive new product/service ideas directly competes with maintaining older, more established ones that pay the bills and keep the lights on. However, in contrast, Lean Startup organizations usually invert this model, with 10% going to core, 20% to maintaining, and 70% to new product/service ideas,14 since there’s nothing to maintain and much more to grow when you’re first starting out. As organizations mature, the scales tip toward supporting and maintaining core product/service lines, as well as enhancing them, which causes the allocations to shift and be more heavily weighted to the left.

Developing Your Investment Allocation Targets

Setting investment allocation targets correctly may take several budgeting cycles to accomplish. A team comprised of senior and mid-level leaders must work together to establish and then periodically review the organization’s targets. The gauge for success is reflected in an organization’s price to earnings (P/E) ratio.15 Comparing industry P/E benchmarks, NPSs, or consumer analytics may help to determine whether the targets need to be adjusted up or down. For example, a drop in NPS may signal too much time and effort being spent on innovation, at the expense of enhancing your core product/service lines.

Also, any changes in the factors mentioned above may be cause for adjusting the allocations as well. A company whose business model was in the Lean Startup phase may move toward becoming more mainstream, resulting in adjustments to the allocations to maintain its market share. Or inversely, an established company that continually loses ground year over year due to market disruption by a competitor may need to adjust its allocations and spend more on new product/service idea generation and development than it has in the past to regain its market share and stay competitive. Therefore, how much is enough in each category fluctuates and will be based on your company’s overall business strategy, competitive position in your industry, and maturity level.

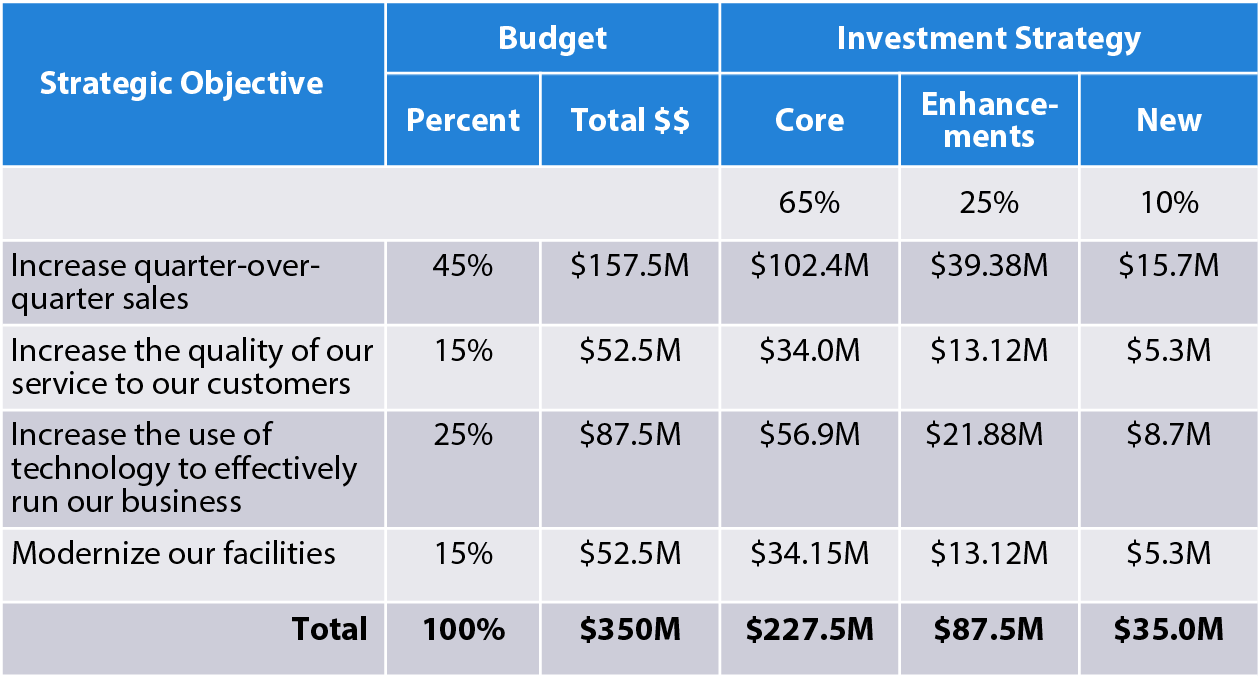

Setting investment targets for New Horizons

Returning to New Horizons, once the objectives were identified, the leadership team revisited their investment strategy to determine what percentage of the available investment capital could be spent on core, enhancements, and new product/service ideas over the next year. Under the dealership’s current strategy, its allocation targets had been set at a 70/20/10 split for the last several years. Given the organization’s current challenges, Jim and his leadership team believe the targets require adjustment to 65/25/10 to address the pressing issues facing the organization. As you can see in Figure 6-10, the objectives act as levers that can be manipulated by adjusting the spending amounts either up or down, depending on the decisions made during the strategic planning process.

Figure 6-10. New Horizons yearly investment strategy by theme

Overall, because the dealership sells a physical product that must be bought and enhanced with additional parts at the dealership, it can’t bring down the core and enhancement costs much on objective #1 of increasing sales quarter over quarter. The 5% shift from core to enhancements, while holding new spending steady, should be enough to accomplish the upgrades to the dealership’s systems and facility. By proactively setting the direction of its innovation and investment spending, Jim and his leaders are intentionally becoming masters of their destiny: defining their mission and vision, setting their strategic direction, and then putting the capital behind these activities to drive value creation and delivery for their customers, stakeholders, and the dealership. Lean leaders must develop the rigor and discipline to proactively plan where their company’s money is going to be spent, because innovation, and the value creation that comes from it, doesn’t happen by chance. It must be intentional, deliberate, and consistent activity that happens quarter over quarter, year after year.

Developing Your Strategic Roadmap

I once worked with a customer who told me he had just sat through a two-hour meeting in which the leaders of the company hotly debated the spending of another $2 million to finish a project that was a year overdue and $3 million over budget. By the time it was complete at the end of the current year, the opportunity they had been working on had passed them by, and the product that was going to be rolled out at the end of all of this effort was obsolete. However, many of the leaders felt they were obligated to complete it out of a sense of loyalty to the CEO, since it was his pet project. Unfortunately, there are countless initiatives in corporate America that should have been killed, stopped, or cut, but no one had the courage or recognized the need to do so when the strategic direction of the organization changed, or the competitive advantage they were trying to capture ceased to exist. Because of this lack of corporate courage or good stewardship, billions of dollars are wasted every year on initiatives that add very little or nothing to the bottom line. In the situation I just described, the company’s leaders will have spent $10 million on something that now creates very little value for the company and its customers. So, to turn the corner and become a value-generating organization, the ability to respond to change must become a part of your corporate DNA.

When developing your strategic roadmap, two constraints must be taken into consideration: your investment strategy and the amount of investment funding available per budget period. Both constraints limit the type and amount of work that can be accomplished in any given budget period. Therefore, an organization’s limited investment funding must be appropriately allocated, based on the company’s investment strategy and sense of urgency that exists from changing market conditions. The following four key ingredients are necessary to build an initial first-year, rolling wave strategic roadmap:

Strategic objectives and competitive opportunities

Tactical plans with delivery timeframes and cost estimates

Investment strategy and funding allocations

Let’s look at how these ingredients come together to assist New Horizons in their efforts to develop their roadmap.

Building the New Horizons Strategic Roadmap

Overall, the strategic direction for the New Horizons service department in the next 12 months focuses on the objectives listed in Figure 6-11, which represents the anticipated investment spending this year across the four strategic objectives and three investment strategy categories. The anticipated spend within the service department is $17.5 million, which, based on total budget estimates (Figure 6-10), makes up about 20% of its anticipated investment spending this year across the three investment strategy categories.

Matching the investment strategy to the yearly strategic objectives, investment allocations, and tactical plans gives New Horizons’ Lean leaders a concrete picture of how they will create service department value over the next 12 months. New Horizons’ mid-level tactical managers used the cost estimates obtained from the tactical plans to work together to balance these factors and assign funding to the plans, based on the investment allocations and budget targets, to ensure the dealership’s investment spending matches its investment strategy. They achieved a balanced budget by remaining within the total yearly budget targets and will be able to add all of the work described in their canvas to their strategic roadmap.

Figure 6-11. New Horizons service department investment allocations by theme

This type of clarity is achieved only through strategic planning at the strategic (enterprise) and tactical (mid-level) levels, allowing New Horizons to lay out a roadmap based on facts and logic instead of hunch and intuition. It’s an integral part of ensuring that strategic objectives are well-planned and that they intentionally guide how value is created and delivered. Now the managers are ready to construct the first part of the roadmap, by placing the tactical plans on it, based on their end delivery timeframes. Table 6-1 depicts the New Horizons Service Department Strategic Roadmap at the tactical plan level.

For example, the technology team has three major efforts underway this year: the dealership computer hardware upgrade, the service and repair mobile device app, and the loaner car program system upgrade. Because the first one is due in the next 90 days, it’s scheduled to be completed by the end of Q1. The second one is due to be completed within the next 6 months, so this work is placed on the roadmap to be completed by the end of Q2. The last one is set to be delivered in Q4, since its target date was set to be within the next 12 months. Remember, the tactical plans are placed on the roadmap based on their completion date, not their start date. Going forward, the roadmap will be used to communicate out to stakeholders the progress against both the plan and KRs, as well as being used in prioritization efforts to ensure the teams don’t get overloaded and require additional assistance (such as contract help) to complete the work.

Year 1: Q1

|

Year 1: Q2

|

|

Year 1: Q3

|

Year 1: Q4

|

$4.375m/quarter Run Rate | |

The last step in constructing the roadmap is to place the operational tasks on it, to determine the minimum viable product (MVP) release plan.

Releasing Value in Increments: MVP Release Planning

All the preceding activities were performed to be able to identify how to chunk the work and release it in stages to create incremental value through the creation of an actionable plan, known as the minimum viable product (MVP) release plan. It’s the responsibility of the mid-level tactical managers who work with the teams to clarify the MVP operational tasksets that deliver value within each release. Each task is assigned a priority based on business and customer value and then laid out on a timeline or release plan for execution and delivery. Each time segment in the plan represents a release of bundled tasks, or in other words, the MVP feature set developed to deliver incremental value. The capacity of the teams and the length of the execution window determine how much can be included in each release.

The MVP release plan is prepared by the tactical managers and gemba teams so that it’s clear when work needs to occur for each task. It also aids in communicating with other parts of the organization, such as the marketing and operations teams, as to when tasks will be ready to release out to the market. Using this process, a product/service is delivered incrementally, instead of all at once, based on what makes sense to the market and what customers find valuable. Releasing it in chunks also allows the organization to learn about what is valued in the marketplace through customer feedback, along with being able to start to recoup its investment by generating a revenue stream and payback period, sooner rather than later.

Completing the MVP Release Plan

To complete the release plan, the tactical managers work with the gemba teams to determine which operational tasks, located underneath each tactical plan, add the most value. The knowledge gained during the previous phases forms the basis of prioritization in terms of high, medium, and low value compared to each other. The priority of a task also determines the execution windows in terms of near-, medium-, and long-term timeframes. The highest priority, near-term tasks are grouped together at the top of the list, then the medium ones, and finally the lower priority, longer-term ones. In this manner, a prioritized list based on strategic fit, business value, and delivery date is created.

Keep in mind that both the roadmap and the release plan represent a rough estimate of the anticipated work for the next 12 months. As the tactical managers continue to learn more about what’s required to deliver each tactical plan through the decomposition and continuous refinement of the tasks underneath, some movement and adjustments may occur. Also, the organization’s priorities might shift, or a hot new product/service idea may create a new plan that requires immediate development to seize market opportunity. So changes to both the roadmap and the release plan are inevitable. Remember, nothing is written in stone; responding to change and having the flexibility to quickly shift priorities are why all this planning happens in the first place.

However, the current period investment and budget targets must be maintained. As a Lean leader, you will always be constrained by your investment funding targets because you can’t spend what you don’t have. If more funding is necessary to seize a market opportunity, then these targets will need to be revisited or some scheduled work from one of the current tactical plans will have to be deprioritized and pushed out. But the timing and feasibility of making a change must be considered. Changing things up in the middle of a release window is not a good idea. If adjustments are necessary, they usually occur at the beginning of a new release cycle. This gives the organization time to complete the scheduled work in progress (WIP) for the current release and then shift its focus and funding before work begins on the next one.

Building the New Horizons Service Department MVP Release Plan

Having developed their strategic objectives, competitive opportunities, and tactical plans, as well as determining their investment strategy, the New Horizons service department budget sits at approximately $17.5 million. With the New Horizons Service Department Strategic Roadmap in hand, the tactical managers meet with their teams to construct their current year, quarterly MVP release plan. Working off the 12-month strategic roadmap, the tactical managers first prioritize the tasks based on business and customer value and then assign a priority based on when they require development effort. They work through all of the tasks on their list in this manner until the top-priority items in the current (Q1 in Table 6-2), near-term (Q2 in Table 6-2), medium-term (Q3 in Table 6-2), and long-term (Q4 in Table 6-2) timeframes are assigned to a release.

Once complete, the gemba teams can begin work on planning the next release, knowing they are working on things that will definitely create and deliver value for New Horizons’ customers, stakeholders, and company, which in the end creates the win/win situation that Jim and his team wanted to achieve.

Year 1: Q1 MVP Release #1

|

Year 1: Q2 MVP Release #2

|

Year 1: Q3 MVP Release #3

|

Year 1: Q4 MVP Release #4

|

Conclusion

Leading enterprise wide means spending time to develop your CSDM framework so that you can empower everyone within your Lean enterprise to work toward achieving its strategic objectives. By systematically identifying your competitive opportunities that are completed through the development of tactical plans and operational tasks, you build an organization that allows everyone to participate in the process of setting the course and then fulfilling its vision. All of the activities that a Lean enterprise undertakes must be tied back to its strategic objectives; otherwise, there’s no reason to undertake them. In this way, waste is removed, and only value-adding activities are undertaken to fulfill its mission and bring its vision into reality.

When companies don’t spend the time to develop their frameworks, it causes organizational drift: the organization drifts aimlessly without direction, hoping the activities it undertakes somehow result in value delivery. Product/service releases become a haphazard cluster of unrelated activities that may or may not deliver value. Hope is not a strategy, and when leaders at all levels within the Lean enterprise forgo making the tough decisions that are necessary to develop a concerted plan, they are not doing themselves or their staff any favors. More often than not, their inability to make the tough calls doesn’t mean those decisions aren’t made. In this situation, the responsibility falls to tactical managers, operational team leaders, or even the gemba teams themselves to make these decisions and the company continues to exist. If what an organization truly seeks is to create and deliver value, then leadership at all levels must be held accountable. After all, you would never board a ship or get on a plane if you knew that the captain at the helm or the pilots in the cockpit had no intention of doing their job that day—or worse yet, that they weren’t fully committed to having a safe and success cruise or flight…right? Those that follow leaders count on them to lead. Period!

So if you think about it, when a company’s leadership doesn’t develop its “Enterprise True North” and chart its course beforehand, they are in a sense saying, “Sorry crew…you’re going to have to figure this one out on your own. We’re sitting it out. Best of luck!” It sounds laughable, but when you’re out in the middle of the ocean or 35,000 feet in the air, it’s cause for panic. As a Lean leader, you must hold yourself and other leaders accountable to give the crew a plan to operate inside of and be able to make sound tactical and operational decisions. That way, if we come upon a storm or hit some rough turbulence requiring the crew to slightly alter course or turn on the seat belt sign, the decisions they make in these situations will be grounded in fact and are well-informed ones.

Don’t underestimate the power of developing your CSDM framework because, in the end, it also feeds decentralized decision making through empowerment and transparency, leading to the ultimate goal of creating and delivering both customer and company value.

One of the best ways to create this kind of value is to innovate, which is the focus of the next chapter: leading innovation.

1 Michael Shirer, “IDC Forecasts Worldwide Spending on Digital Transformation Technologies to Reach $1.3 Trillion in 2018”, ICD, December 15, 2017.

2 Bruce Rogers, “Why 84% of Companies Fail at Digital Transformation”, Forbes.com, January 7, 2016.

3 Wikipedia, s.v. “Helmuth von Moltke the Elder”, last modified October 10, 2019, 08:42.

4 Barbara Farfan, “Amazon.com’s Mission Statement”, The Balance Small Business, March 20, 2017.

5 Guerric de Ternay, “Amazon Value Proposition in a Nutshell”, FourWeekMBA.com, accessed June 8, 2019.

6 Patrick Heer, reply to “What is Amazon’s unique value proposition?”, Quora, June 14, 2017.

7 Gail S. Perry, “Strategic Themes—How Are They Used and WHY?”, Balanced Scorecard Institute, 2011.

8 “Whitepaper: Is Keeping Pace the New Standstill?”, PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2016, 1.

9 Wikipedia, s.v. “iPod”, last modified October 18, 2019, 21:07.

10 Wikipedia, s.v. “Sony Music”, last modified November 11, 2019, 09:20.

11 John Battelle, “The 70 Percent Solution: Google CEO Eric Schmidt gives us his golden rules for managing innovation”, CNN Money, November 28, 2005.

12 Nawal K. Taneja, Airline Industry: Poised for Disruptive Innovation? (New York, NY: Routledge, 2017), 7.

13 Bansi Nagji and Geoff Tuff, “Managing Your Innovation Portfolio”, Harvard Business Review, May 2012.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.