7

Influencing Peers

We turn our focus now to influencing peers, that is, co‐workers important to achieving your goals but who aren't necessarily on a formal team you lead, and over whom you have no authority. Today's leader from the middle has more peers than ever to influence given the rise of matrixed organizations, which is tricky, as influencing peers is a nuanced practice. Not to fear, though, because in this chapter you'll get refined plays to help you be more effective in this aspect of leading across the organization.

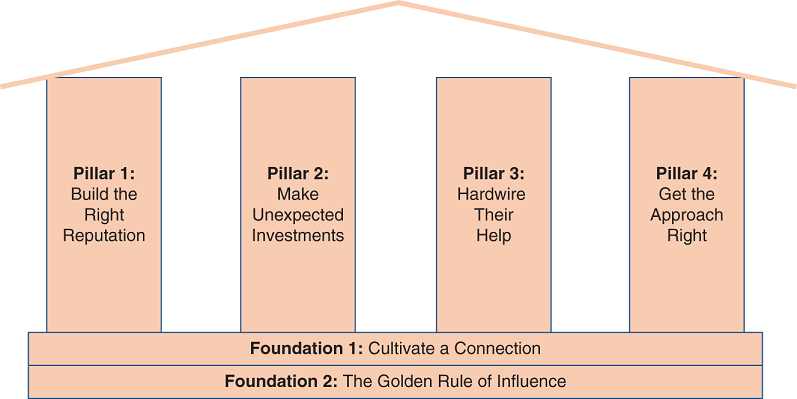

Influencing peers effectively means starting with the right foundation and then building upon it by concentrating your efforts in four areas, or four pillars (Figure 7.1).

Let's first dig into the foundation and then build upwards from there.

Figure 7.1 The Pillars of Peer Influence

Foundation 1: Cultivate a Connection

The truth is, more often than not peers are treated more like potential transactions than potential relationships. You can stand out among middle managers by simply making the effort to make a genuine connection with peers. Just like you would in any other relationship, take the time to get to know them and let them get to know you, and look for common beliefs, values, and experiences to build upon.

Building a connection with a peer also gives you the opportunity to play a unique role, different than in any other workplace relationship. You can be someone they can seek out to safely vent their frustrations, share their worries, commiserate, and in general, confide in. Your arm's‐length distance is an advantage here; they don't report to you directly or indirectly as a team member (or vice versa), so they can be more open and see you as a much‐needed outlet. Not only can this lead to a rewarding relationship, it puts the building blocks in place so that your peers know when you collaborate on something, your intent is pure.

Now, it can be difficult to put this connective foundation in place when dealing with a difficult peer. But I offer one powerful sentence that can change that. Before engaging with the problematic peer, remember this:

We all fear something, love something, have lost something.

Fear explains so much of undesirable human behavior. It engages our brain in the wrong conversation and distorts reality. It causes us to act in ways we don't intend or are unaware of. And the truth is, we all fear something. Even you. So, there's a decent chance that it's fear in some form that's making your difficult‐to‐work‐with peer so difficult to work with. Perhaps they really fear failure, criticism, change, or rejection (yes, even rejection from you). Keep that in mind when trying to connect with this person. Ponder what the peer might fear, how it's affecting their behavior, and how you can better interact accordingly.

On the more positive side, we all love something, are loved by someone, and have the capacity to love. So even that miserable co‐worker is loved by somebody, even if it's not you. And guess what? To be loved requires qualities worth loving. So, expand your own capacity to love and try to see those qualities in that difficult peer. See them for what they are that's wonderful to someone else rather than for what they aren't according to your narrower point of view.

Lastly, we most certainly have all lost something, including that difficult peer. It might literally be a loved one lost, even recently. Or perhaps your peer has lost their dignity, support, sense of confidence, or career momentum—all things that would have an understandable impact on one's behavior. Consider that and know that it's worth your compassion and patience when interacting with him or her.

Foundation 2: The Golden Rule of Influence

There has been plenty written on how to influence when you don't have any authority. Much that's shared in this book can be used to influence those whom you have no formal power over. But I believe the essence of doing so boils down to one basic directive, well‐articulated by author Dan Schwartz. If you want to influence without leaning on your position power, think about people in your life who had no authority over you, yet were tremendously influential. Odds are, they had such an impact because they did it by doing four things: caring, listening, giving, and teaching (which we'll talk more about shortly).1 That's it.

I think of this as the Golden Rule of Influence; influence others the same basic ways you were influenced. It's especially powerful for influencing peers you have no authority over because your willingness to care, listen, give, and teach isn't the norm and will be seen as true gifts. The absence of authority isn't a barrier to influencing because you're drawing on the basics of human emotion and empathy.

Pillar 1: Build the Right Reputation

You influence peers when you draw them to you, creating a desire for them to work more closely with you. That requires building a very specific reputation, one based on the fact that peers want to know two things about you.

First, can you be trusted? They don't work with you as often as they do others and they're already surrounded all day, every day, by people with hidden agendas.

Second, peers want to know if you're worth collaborating with to achieve a goal, that you're highly competent and credible and worth taking time away from those they work with more directly.

You build this very specific reputation when you become known for the following things.

1. Showing a willingness to help

Peers know you're not obligated to help but want to know you're genuinely willing to do so. This doesn't mean you have to be forever volunteering your services to every peer. Just being responsive to requests for help is an influential thing to be known for. In fact, one study showed that leaders who engaged in reactive helping (requests for help) drew more gratitude from the recipients than when they acted as a proactive helper.2 Peers don't always fully appreciate you inserting yourself into their problem, however well‐intended your offer of help is. Not that you can't be proactive in helping, it just requires more subtlety, like asking peers questions that will help them find the answers versus jumping in and outright solving their issue.

2. Exuding expertise in your area

Peers want to know that they can defer to you with confidence and that you've got your part of the mutual task well covered. You exude your expertise by always being well prepared for any meeting where you have to show leadership in your area of responsibility.

3. Being objective, logical, and data based

Your peers won't want to interact with overly emotional, uninformed decision‐makers. If they're going to work with someone outside their chain of command, they'll want to know that their input and efforts will ultimately be a part of smart decisions made.

4. Representing your peers fairly, consistently keeping their point of view in mind, even when they're not present

Why would a peer want to help you or work more closely with you if you didn't?

5. Taking ownership of issues and never passing the buck, blaming, or backstabbing a peer

This goes straight to the core of trustworthiness. If peers are going to spend discretionary effort working with you, there's no room for you to do anything but consistently act in a trustworthy manner.

6. Shining in times of adversity

This is about being a beacon in dark times. Moments of adversity allow you to create impressionable moments, especially for those who might not see you in action every day.

7. Being sure to credit peers and give them honest praise and appreciation, never grabbing the glory

Your peers will also want to know their choice to engage more deeply with you will be a rewarding experience.

8. Exuding enthusiasm and a great attitude

It's hard not to be drawn to people who seem to love what they do. Especially since your peers likely already have to deal with plenty of negative nellies within their own reporting lines and teams.

9. Being vulnerable, admitting mistakes, and asking for advice

Peers have enough competition within their own silo of hierarchy and enough reason to feel as insecure as any other human being. So, they won't want to feel like they're interacting with a prima donna know‐it‐all when they don't have to.

To heighten your success and reputation in leading from the middle, make the effort to build a reputation for all the above. To build it, be it (consistently).

Pillar 2: Make Unexpected Investments

This goes beyond the Golden Rule of Influence (influencing others the same basic ways you're influenced). This is about going above and beyond to help your peers win and grow. If your peers indicate a willingness to receive this kind of investment from you, it's incredibly powerful because my experience shows that others outside their hierarchy will rarely make such an investment.

So, what do unexpected investments look like? The most powerful kinds come in two forms.

1. Peer‐to‐peer feedback

First, take the time to not just enlist and work with peers to achieve a goal, but to teach and mentor them along the way. Doing so includes helping them learn from thoughtful feedback, which can be highly effective as peer‐to‐peer feedback is the most objective kind.

But giving feedback to peers has one unique requirement. Harvard research indicates that peer‐to‐peer feedback doesn't work unless the recipient of the feedback feels truly valued by the giver of the feedback. In absence of feeling valued, the receiving peer will simply avoid giver peers and their feedback, instead seeking out more self‐affirming co‐workers. The researchers call this process “shopping for confirmation.”3 In other words, your peers may not want you shining a negative light on them (they get enough of that in their hierarchy); they'd much rather have you making them feel good about themselves. That is, unless they know you truly value them. Then your feedback is seen as you trying to give them a gift in the form of feedback.

To show you truly value peers, do the unexpected and compliment them on who they are, what they do, or how they do it. Be specific. Precision implies you care enough to notice and to take the time and brainpower to thoughtfully articulate your appreciation. As mentioned before, you can also seek out their feedback and advice (making it a two‐way street), being sure to listen and act on it if appropriate.

2. Outright advocacy

The second major source of unexpected investment you can make in peers takes the form of outright advocacy. This is where you evangelize for what your peers are evaluated on, a potent way to show you're invested in their success. You do so by taking three specific steps.

Step 1: Find out what your colleagues get evaluated on. If they do a job similar to yours, you probably already know, but if they work in a different function, it's likely quite different. For example, your peer in R&D might get rewarded for being innovative, the co‐worker who works in the plant gets measured on safety and efficiency of production, the person in finance on encouraging a balance of smart spending and cost cutting. If you don't know, ask people who work in that function what's important to demonstrate in that function.

Step 2: Find opportunities to share positive feedback on what matters to who matters. That is, share the praise with the co‐worker's boss—praise on what matters and is measured as success in that peer's world.

Step 3: Let the peer know you're bragging on them to the boss. Do this from time to time. At other times, don't tell anyone—it tends to get back to the people anyway that you've been spreading positive gossip about them to their boss. This positive “blindside” is even more powerful than bcc'ing people on a praise email you wrote to their boss.

Making unexpected investments can lead to unexpectedly influential relationships with your peers. So, consider these two contributions of your time and effort.

Pillar 3: Hardwire Their Help

You seek to influence peers because you ultimately want their help on something in some form. The first two pillars involved indirect triggers; building the right reputation and making unexpected investments, both of which lead to eventual influence over time. But there are also mechanical methods to more immediately influence peers, ways to hardwire your influence by creating direct triggers. Here are the most effective ways.

1. Reciprocity

This is the cardinal rule of influencing peers. Do something for them and you ingratiate them—they'll feel compelled to do something for you. This doesn't mean be disingenuous and manipulative, giving something only so you'll get something. But it is human nature to reciprocate, and there's nothing wrong with using that to your influencing advantage.

And after doing something for them, you don't need to point out, even subtly, that now they owe you; they'll naturally feel a sense of obligation. It will be unspoken when you come to them for help; they'll remember your assistance and want to return the favor. After all, if you're doing it right, what you gave them helped them achieve a goal or avoid a negative, both things worthy of reciprocity.

2. Give them 10 percent more

This is a close cousin to reciprocity, but deserving of its own mention. If you always add value in your interactions with peers and visibly give that extra effort, they'll feel the need to bring their best, helping selves to the table as well when engaging with you. That's a form of direct influence.

3. Link your agenda to their agenda

Nothing gets people on the same page quicker than striving for common goals. So, don't think of your peers as a list of people you're trying to round up and corral to get your work done. Find out what their agenda is and make the connection to yours. Leveraging a common purpose, vision, mission, or goals are all great ways to do this.

4. Solve a problem together

It's one thing to help a peer or enroll their help. It's another to identify or get involved in a thorny mutual problem and tackle it with your peer in partnership. The ups and downs of problem‐solving will pull you closer together, another direct form of influence.

Pillar 4: Get the Approach Right

Influencing peers requires knowing how to approach them in a way that doesn't raise defenses, suspicions, or hackles. After all, you don't have any hierarchical working relationship with them, so just what is it you want from them anyway? Here's how to get the approach right so you'll stick the landing.

1. Be clear on your context

Peers will know less than others about where you're coming from as you approach them. So be transparent in your asks and offers.

2. Know what you're asking

Related to the above, be clear and direct in your asks and what will be required from them. Don't downplay the size and scope of the ask. Understand and acknowledge if what you need from them could present problems in any way and offer ideas on how that “pain” can be mitigated.

3. Know that they don't care about your deadlines

Also related to the above, all too often I've seen well‐meaning middle managers approach peers for help on something, impressing upon them the urgency of the situation. Not ideal. Your emergency is not their emergency. Instead, plan out when you might need to enroll a peer on something and give them plenty of time and options for getting involved in the way you need them to.

4. Know your peers' job and motivations

I don't mean know everything about their role and all their heart's desires. Know enough about what their job entails, how your request intersects with that, and at least the basics of how they're rewarded. This allows you to have a more informed ask with more tangible, meaningful benefits to your peer that you can articulate upon your request. This is about encouraging the expenditure of their discretionary energy to aid your cause, so understanding where your peer is coming from is essential.

5. Let them have the ideas

As I alluded to in Chapter 5, what are you more motivated to work on, an idea that you came up with or one that was dictated to you by someone else? It's not even close. So, as you approach, engage, and ideate with peers, make them feel as if they came up with the ideas you want executed. Again, not in a disingenuous, manipulative way, but in a more deferring manner.

For example, ask questions that will elicit ideas, and when your peer shows excitement and desired ownership of one of those ideas, step back and defer to your peer, letting them run with the idea and continuing to shape it. Subtly refer to it as their idea and talk about the support you want to give to make their idea happen. (By the way, this tactic is not only effective across the organization with peers, but in leading up and down the organization too.)

6. Exert the opposite of peer pressure

I always thought peer pressure in the traditional sense was the wrong approach for any peer to use in an attempt to influence me. Getting me to do something because all my friends were doing it worked as a kid, and only works as an adult in more subtle, social influencer ways. As in, read this book because 657 people have given it five stars on amazon.com, and so forth. But peer pressure as a direct play in the workplace? Not so much. Your workplace peers won't succumb willingly and with good feelings about it just because you use old‐school peer pressure. You already know this and likely wouldn't even consider it. But I find that leveraging the exact opposite approach to peer pressure is useful.

Here's what I mean. When enrolling peers for help, make a point that they won't need to adjust to you/your team's exact style and way of doing things. Instead, encourage the exact opposite. Invite them to bring their unique, individual self, skills, and style to the table. Make the opportunity to work with you feel like an opportunity for them to express their full selves in a safe environment, something they might not be feeling they can do in their current hierarchical structure.

So, by applying the specific tools in this chapter, you'll have peer power on your side. Let's continue turbocharging your ability to lead across the organization (and up and down as well) by focusing on a wildly important specialty skill, leading change, in the next chapter.

Notes:

- 1. D. Schwartz, “Be a Ground Floor Leader: Influence Your Peers,” td.org (July 30, 2015).

- 2. H.W. Lee, J. Bradburn, R.E. Johnson, S. Lin, and C. Chang, “The Benefits of Receiving Gratitude for Helpers: A Daily Investigation of Proactive and Reactive Helping at Work,” Journal of Applied Psychology 104, no. 2 (2019): 197–213.

- 3. S. Berinato, “Negative Feedback Rarely Leads to Improvement,” Harvard Business Review, hbr.org (January 2018).