Chapter 3. Brand Story

Throughout this chapter, we will look at the six essential parts of a lean brand story: positioning, promise, personas, personality, product, and pricing.

I’ve never met someone who did not aspire to be something more. Even Homer Simpson, with his absolute lack of will and ultimate disregard for the future, at times aspired to be a better husband, a fitter couch potato, a less miserable son to his old man. I’ve heard 5-year-olds state with absolute certainty that they will be president. Someone is sweating his head off right now at some ridiculously expensive gym because he aspires to be fitter. As you read this, someone is pulling an all-nighter studying to earn class valedictorian status—or maybe even reading this book to up her brand game (in which case I highly appreciate it!). I’m pretty sure someone is daydreaming to the sound of Bruno Mars’s “Billionaire.” Someone (perhaps you) aspires to build a successful product that customers open their wallets and hearts for. If that is indeed you, please hold on to this thought: aspirations.

Behind every great brand is a promise that fulfills its customers’ aspirations. We are in the business of taking customers from A to B, where A is who they are today and B is who they want to be tomorrow. Consider the products you love—sports attire, note-taking apps, electronic devices, chocolate ice cream...this book—and how they’ve made you feel closer to whom you want to be.

When most people think about aspirations, they imagine long-term dreams or perpetual objectives. But in reality, aspirations come in all sizes, time lengths, and levels of difficulty. After all, an aspiration is nothing more than a pursuit—an urge that influences our daily decisions. Whether that aim is to become a more organized worker, a more inspired creative, or the president of the United States is irrelevant.

All human aspirations are opportunities for brands to build relationships.

Here are some sample aspirations to think about:

Be independent and perceived as such by others. Become an autonomous individual by purchasing products and services that empower you to do more and better on your own.

Be more relaxed. Live a less stressful lifestyle by purchasing products and services that help release different kinds of tension.

Be unique and perceived as such by others. Express yourself and your worldview by purchasing products and services that let others know who you are and reflect your identity to the world.

Enact a new role in life. Embody a “new persona” by purchasing products and services that help you attain a new professional or personal position.

Engage in better relationships. Improve the way you connect with other human beings by purchasing products and services that strengthen your social circle and increase your sense of belonging.

Be more stable. Avoid danger by purchasing products and services that increase your safety.

Be well-known. Become accomplished by purchasing products and services that help you become more recognized and reputable.

Be a genuinely better human being. Grow individually by purchasing products and services that boost your professional, spiritual, and emotional development.

Forget Everything You’ve Heard About Brand Stories

Our mission for this chapter is to understand whom we’re selling to and learn the best way to show them who we are, what we offer, how we’re different, and how we promise to help them. The good news is that there’s no need to reinvent the wheel. Human beings have been learning via stories forever, and there’s simply no better tool to send our brand message across.

For some reason, when they hear about “brand stories,” some people imagine their company’s CEO reading to a potential buyer sitting on his lap, in an altruist display of emotion and mutual love. Rewind. Yes, there might be some reading. And yes, we need the CEO on board. But, while emotion is a part of the whole thing, please remember this:

Your brand story’s “happily ever after” involves open wallets.

Seth Godin has an interesting thought on the matter:

Stories and irrational impulses are what change behavior. Not facts or bullet points.

Some other people hear me say “brand story,” and “storytelling” immediately comes to mind. I’d like to let you know that “telling” is not what we’re doing here. We’re aiming for “story-showing.” Telling isn’t enough. Brand communications are not about explain-time, justify-time, defend-time...blah-time. Please keep the idea of showtime close to heart. This is why Chapter 5 is all about “story-showing”—feel free to take a peek if you’re curious at this point.

But before we deal with ways to show our brand story, we need to create one.

I know social media, digital channels, videos, websites, and many other tools are appealing at the moment. I know that you think they might help your product scale instantaneously (miraculously); that they’re just what the doctor ordered. I also need you to understand that you better stay away from them unless you have a story to tell.

Otherwise, digital channels just have a way of...well...swallowing you.

Remember this:

Digital channels are just tools to show (what should be) a meaningful brand story.

Having a brand story is not optional. If you don’t start writing it, please worry because—mark my words—someone else will write it for you. In my experience, only extremely disgusted or extremely pleased customers will put any effort into contributing to your brand story, so imagine how that would turn out without your attention. Brand storytelling is your unique chance to be persuasive and make the case for your product.

To take full advantage of this opportunity, we will answer five simple questions for our customers—though, as you’ll see, there’s really one big, profitable, underlying question (Why should I buy from you?):

Customer asks | Customer really thinks | |

Positioning | “How are you useful to me?” | WHY should I buy from you? |

Promise | “What do you promise to do for me?” | Why SHOULD I buy from you? |

Personas | “What do I need/want from you?” | Why should I buy from you? |

Personality | “Who are you?” | Why should I buy from YOU? |

Product | “What will you offer, over time?” | Why should I BUY from you? |

Pricing | “How much is this going to cost me?” | Why should I BUY from you? |

First Things First: What’s Your Name Again?

Someone has to come up with a name for the “fear of naming a new product.” I am positive that this is an actual phobia. Side effects include headache, insomnia, anxiety, and utter bipolarity. I also blame this entire situation on superstitious nonsense.

Listen: I’d be a terrible marketer if I told you that your name doesn’t matter. It does, deeply. What I have an issue with is the amount of time some people waste naming something that isn’t really anything yet. Somehow, we’ve come to believe that even before the product has some sort of clear function (i.e., adds value), we will reach nirvana and come up with a million-dollar name. Said “million-dollar name” will then take a mediocre product from zero to millions within a day.

Wake-up call: there is no million-dollar name. There are, if you work hard enough, great products that make millions in the marketplace aided by an equally great name. Bottom line:

A great product deserves an equally great name that does it justice.

That being said, there are some ways in which a fitting name can make the difference for your product. If you already have a name, feel free to jump to Part III, where you’ll learn how to measure its impact. If you are just getting started, you’ll find the process much easier if you answer these questions (and please do):

Look around. What names are your competitors using to brand their products? (Write at least 20.)

What word or words encompass the most important thing your product is here to change? (Jot down a list of at least 20.)

Go literal: write down words commonly used in the industry that you’re in, the type of product you’re trying to sell, and the people who will buy it.

Sometimes we only think of nouns (i.e., things), but there’s actually a vast list of verbs (actions) and adjectives (descriptors) that are great sources for names:

Dropbox (verb + noun)

Pinkberry (adjective + noun)

Goodreads (adjective + noun)

Instagram (adjective + noun)

MySpace (adjective + noun)

Go figurative: use metaphors; find ideas that are related to the experience that you are creating.

Which of these words (or combination of words) could best convey what your product does? (Narrow it down to 10.)

Which of these options is most original and therefore recognizable in the marketplace?

Which of these options can be trademarked and does not interfere with another company’s legal rights?

Gather Your Brand Ingredients

Remember the recipe we just learned about a few pages ago? That Lean Branding recipe included the 25 ingredients that we will be building throughout Part II, and the time has come to find our brand story ingredients: positioning, promise, personas, personality, product, and pricing.

Positioning: How Are You Useful to Me?

We’ve already discussed aspirations: those possible selves that consumers are constantly striving for. We saw how brands can provide shortcuts to satisfy these aspirations and build relationships that go beyond a simple feature set. Our brand adds value when it helps a customer go from A to B, where B is whom they want to be. But just how do we go about making them understand and remember what we’re here to do?

That’s where positioning comes around. I know it sounds like a complex term, but it really isn’t. If we are going to enter the marketplace to help customers go from A to B in their lives, we need to position our brand as an aspiration enabler. As a problem solver. As a propeller. Positioning is simply finding and taking a space within the marketplace that projects your brand as the “aspiration enabler” for a certain customer segment.

In a nutshell:

Positioning is finding the right parking space inside the consumer’s mind and going for it before someone else takes it.

These questions are key to building your brand’s initial positioning:[24]

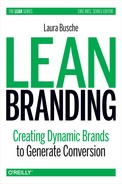

As a first step, consider mapping out who your main competitors are and how your brand’s offer compares to theirs. There is a very handy, visual tool to simplify this comparison. It is called a positioning map, and it will help you understand which brands you are competing with and what makes your offer stand out.

To build this map, select two criteria that your main competing brands and your own can be ranked on. For example, a fashion brand could select price and apparel formality as its criteria. Then, assign one of the criteria to the horizontal axis and the other one to the vertical axis. Finally, map out the brands in your competitive space according to how they rank on both axes.

It is important to understand that this initial positioning is an ideal space that will not match consumer perception perfectly. This positioning map will change over time, and it is your job to make sure that continuous measurement guides any direction changes. Chapter 7 presents strategies to measure whether your positioning is resonating well in the marketplace.

The positioning statement

A positioning statement answers three main questions:

Which space are you trying to occupy?

What is the main aspiration that you are trying to satisfy?

Who else is there (competing with you)?

No need to make our lives any more complicated (this is Lean Branding, remember?). Geoffrey Moore Consulting created a very effective template to create your positioning statement that has been used by companies everywhere:

For (target customer)

Who (statement of the need or opportunity)

The (product name) is a (product category)

That (key benefit, compelling reason to buy)

Unlike (primary competitive alternative)

Our product (statement of primary differentiation)

Fill it out. Done. Use it, use it, and abuse it. You can’t go wrong.

Promise: What Do You Promise to Do for Me?

Keep it short and sweet. This is basically a fun-sized version of your positioning statement, emphasizing on your core value offer. It’s the one thing you promise that will keep customers coming back, crafted into a memorable, short phrase that they can remember easily. It’s your “Save money, live better” (Walmart), your “Remember everything” (Evernote), your “Eat fresh” (Subway)...you get the point.

Bob Dorf[25] has labeled this promise “Bumper Sticker” and has some great advice about how to make it shine. Take a look at the following “Get on It” sidebar. If you still need more ideas for your brand promise, check out the “Inspiration Hack” sidebar on the next page.

Personas: What Do I Need or Want from You?

Every brand story needs characters, and that’s exactly what buyer personas are. We are going to create fake people with very real needs and aspirations to inspire everything our brand is, does, and communicates. This entire book is hanging on the idea that you are aware of who these characters are and are willing to constantly monitor how they act. So stay with me on these simple ways to find out who your buyer personas are and what they want. It’s our only shot at making sure that what they want is you.

Most entrepreneurs will tell you that they “absolutely know the buyer.” There are a few harsh truths that must be told at this point:

Even if you think you know what buyers want or need, this is constantly changing.

Even if buyers think they know what they want or need, sometimes they won’t say it.

Sometimes buyers have no idea what they want or need, but you can find out by observing.

Go out and learn cautiously from what your buyers say, and rigorously based on what they do. This “going out there” is something anthropologists, designers, and professionals from many other disciplines know as ethnography.

Note

Marketers have been using focus groups and surveys for years, but besides not being time- or cost-efficient, they are often performed out of context. Meaning: is there a point in asking someone what she thinks by removing her from the place where she usually does her thinking and pretending she’ll do exactly as she says? I won’t bore you with method wars here, but bear in mind that we are looking for the most efficient way to learn about our buyers in order to make decisions that are not only informed, but also timely.

There are probably a million ways to conduct ethnographic research (i.e., going out there and observing people). For the purpose of remaining lean, let me introduce you to four that are very time/cost efficient.

Secondary research

Look out for data on your buyers from magazines, databases (if you have access to any), newspapers, industry white papers, and reputable sources that you can trust. This will give you a broad sense of how the market is doing and general trends to keep in mind as you observe your buyers.

In-depth interviews

Sit down with as many potential buyers as you can and ask them as many questions as you need to start discovering patterns among them. There are some very specific items we are looking for, and you will find a list of sample questions later in the chapter. Some people suggest you should also interview existing customers who both love and hate your product. In case you are just getting started, and you have no customers to conduct these with, arrange for interviews with potential customers. In Chapter 6, we will come back to this and apply it with existing customers.

Interviews were a vital part of the Apps.co entrepreneurship program in Colombia. Since teams were expected to go from idea to minimum viable product in eight weeks, the program demanded that a number of interviews be conducted during the first few weeks. These interviews would guide the development of the product and the brand that would project it into the world.

In an outstanding case of customer discovery, a mobile app called Bites pivoted from a food delivery intermediary into a tool to improve the on-site restaurant experience. After dozens of interviews with potential customers, the team realized that their market felt fascinated and moved by authentic food photography. They were eager to see pictures taken by other “foodies” and were more comfortable trusting their peers for restaurant recommendations. Perhaps repeating this exercise somewhere else on Earth would reveal different insights. And that, ladies and gentlemen, is the whole point behind conducting interviews while you are building your brand: going beyond your own assumptions.

Fly on the wall

I absolutely love this method. Picture a fly on the wall. That’s pretty much what you’ll be. This type of observation consists of becoming a part of any given environment for a few hours. You are trying to understand your buyers’ context: what threats and opportunities can you spot? If you’re interested in teachers, for example, visit a school for a given number of hours and record as many details as you can about the school day.

In 2012, my agency was hired to build a local politician’s online brand presence. She had already been elected but was having trouble empathizing with the citizens who hadn’t voted for her. During a brainstorming session, we decided to use expressions from citizens themselves to communicate her brand message. We would address naysayers and continue appealing to sympathizers by using their own terms and language.

To do so, we followed the politician in every single public event for four months. We did not intervene or ask any questions during this time. Our team was just present, taking notes and analyzing what came out of citizens’ mouths. Later, we would synthesize these insights and come up with messages that reflected the citizens’ own concerns and satisfactions. Our social media engagement skyrocketed, and the conversation (which had remained stagnant for months) activated around the topics that citizens were actually interested in hearing.

Shadowing

Here’s a classy term for some serious stalking activity—except you will formally approach someone to ask his permission to stick with him for a couple of hours. The idea here is to get a sense of what his particular routine is like, what are some needs and aspirations he might not be willing or able to declare verbally but are visible to you, and what channels would work best to reach him, among others. You must remain unnoticed and avoid disturbing his routine. This is academic stalking.

Take a few minutes to imagine the aspiration that your brand is here to facilitate. Are you trying to make it easier for customers with a fast-paced lifestyle to share their files? Are you trying to provide a healthy or environmentally friendly option in the midst of a toxic marketplace? Are you building an app to optimize the way I spend my time? Are you a political brand offering to bring prosperity and education? This answer is a vital starting point for the observations that you will take note of while shadowing a subject.

For Procter & Gamble, this answer was once “we are trying to offer a better way to clean a floor.”[26] In 1994, the company hired an innovation and design consultancy called Continuum to figure out a way to reinvent the act of cleaning floors. To do so, researchers followed individual people as they cleaned their own kitchen floors. They found out, among others, that “mops worked mostly by the adhesion of dirt to the mop and people seemed to spend almost as much time rinsing their mop as they did cleaning the floor.” To solve it, they designed a new product that would bring their newfound idea of “Fast Clean” to life. The rest is Swiffer history.

As you follow your potential or existing customers, take note of the activities, environment, interactions, objects, and users involved in their routine. These five types of observations belong to a framework called AEIOU (after their initials) that was developed by a group of researchers at the Doblin Group in 1991 to make ethnography easier to record.[27]

Here is what some sample, raw shadowing observations might look like, as coded with the AEIOU framework. You can also use this framework to record your fly-on-the-wall observations:

Subject: John, potential user for our to-do list app | |

Started: 03/05/2013 8AM Ended: 03/05/2013 11AM | |

Type of observation | Notes |

Activities | Getting ready for work Driving to work Picking up coffee before work Accomplishing daily tasks |

Environment | Home: 2BR apartment, NW side of town. Office space in living room. Pinboard next to desk. Monthly calendar pad on top of desk. Coffee shop: dim lighting, slow jazz music. Office: personal cubicle, white light, notebooks scattered on desk. Monthly calendar on cubicle wall. |

Interactions | Drinking coffee, talking to barista, printing a last-minute document, checking email on smartphone, driving compact car to metro station, parking car, taking metro to work. Checking email on desktop computer again. Adds some dates to wall calendar. Added sticky note to computer screen. Completing yesterday’s pending tasks first. Tossing sticky note once task completed. |

Objects | Monthly calendar pad on home desk, cappuccino with low-fat milk, Metro card, printer, 21.5” iMac computer, colored sticky notes, iOS smartphone, monthly calendar on cubicle wall. |

Users | Wife, boss, barista |

After following John for a couple of hours, you already have an interesting set of brand-related questions to continue validating:

Should our brand message include a reference to “keeping all your to-dos in the same place” or “making your to-do list accessible”?

Considering John’s reliance on email, would placing ads on email platforms be an effective communication strategy for our brand?

Would coffee and a desk generate associations with planning and to-do list creation, and therefore be effective images to build our brand’s visual identity around?

Given John’s desire to visualize important deadlines in walls, should our brand message focus on screen-paper (online/offline) integration?

The importance of carrying a field guide

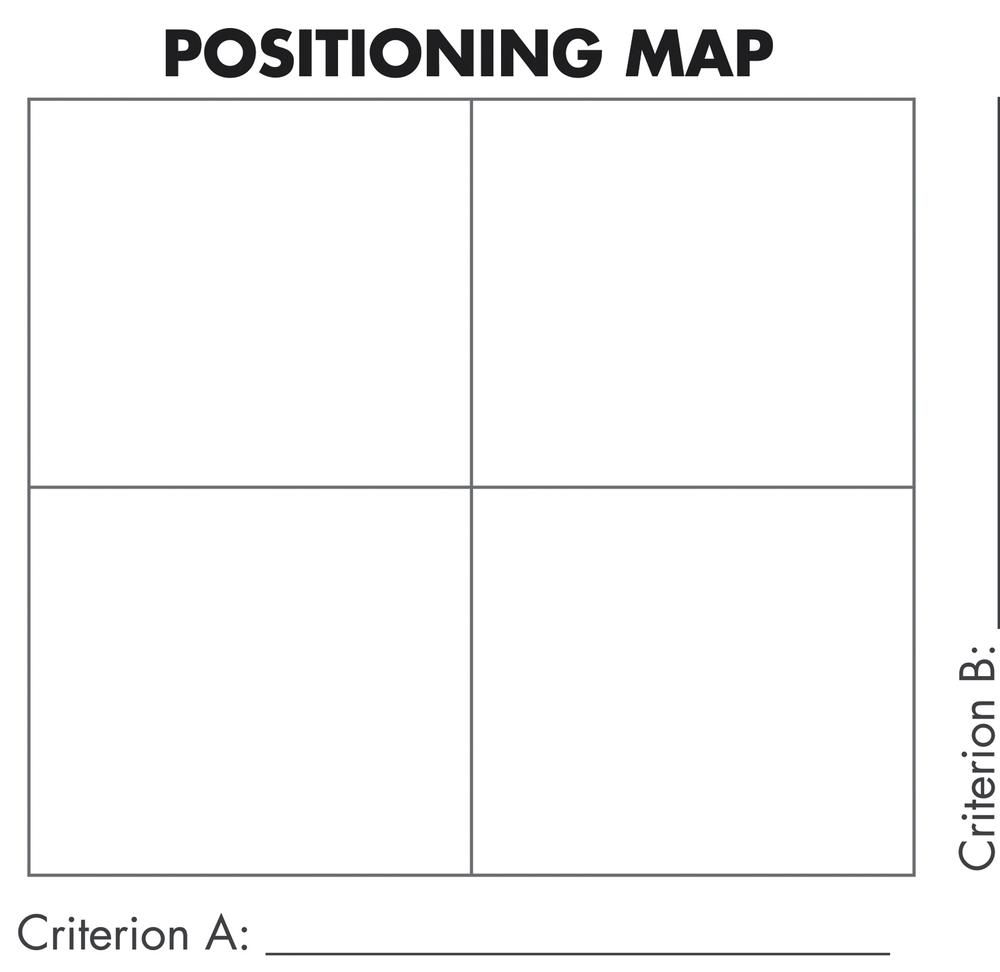

Some general guidelines are to make sure that you select the right people, prepare your interview questions beforehand (but be sensitive to open up to others), fill out a reasonably organized field guide, and keep your eye open for behaviors that deviate from the standard. Also, even if you’re researching buyer personas for a very specific product, make sure that you look at the whole experience. You never know what new ideas may come up.

As promised, next is a sample field guide. Miscellaneous questions like “favorite social media platform,” “car make,” and “hair color” might make sense in specific cases (with car or shampoo brands, for example). Take this guide with you, be efficiently creative, and feel free to edit or add questions as needed.

Now that you’ve interviewed and observed a considerable amount of potential buyers, summarize the patterns you have uncovered in—you guessed it—your first buyer personas. The main characters in your story. Also known as the people we’re going after.

Use the following template to summarize your information:

Personality: Who Are You?

Ever been stuck talking (more like yelling) to a machine when you needed support from an actual human being? That’s how customers feel when your brand personality isn’t there or isn’t coming through. Try this with me: imagine Apple and Microsoft as people. Now think about them going out on a date. If you can sustain their dialogue and picture them for over a minute, both of these brands have done their homework. When they tell you stories, you get “human” rather than “machine”—even though (sorry to break your heart) they are essentially machines.

People relate to people, and if your brand feels like “people,” they’ll relate to you, too.

The American Psychological Association has defined personality as the “unique psychological qualities of an individual that influence a variety of characteristic behavior patterns (both overt and covert) across different situations and over time.”[28] Our personality influences the way we think, behave, and feel with regard to everything that surrounds us. Similarly, brands must react in a marketplace where conditions are uncertain and ever-changing. Creating a flexible, yet strong, brand personality will help us adapt quickly to this environment. Lean brands sail out into the world to discover their customers and can rarely predict the outcome; however, they can always decide how to react to what they find. A brand personality guides us in this agile decision-making process.

For the purposes of this book, we will understand “brand personality” as the humane psychological qualities associated with our brand that dictate its interactions in the marketplace during different situations and over time. By linking your brand with several traits that are traditionally used to describe human personalities, you can build a more relatable story that consumers will engage with.

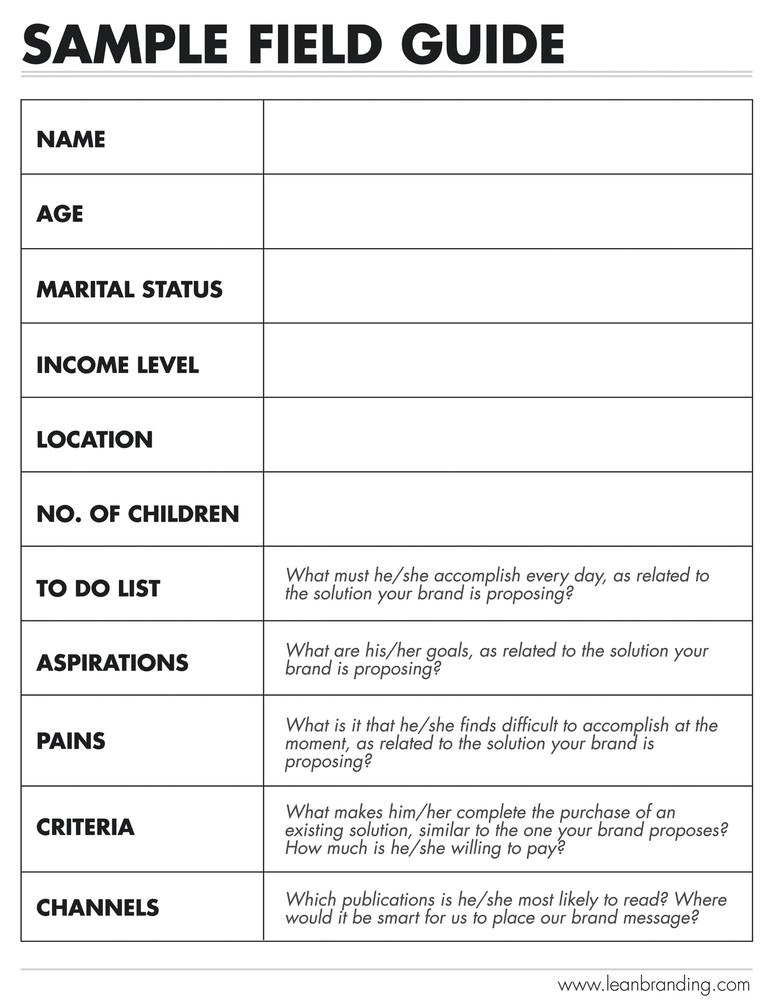

Having followed dozens of startups as they developed sound brand personalities, I have compiled a list of descriptors that can help you create yours. In Chapter 7, you will find out how to measure whether this personality is resonating well with customers and adapt it accordingly. Feel free to include and use other words that apply to your brand. Based on the positioning, promise, personas, and product you’ve described before, which of these qualities fit your brand best?

Good, so what are we supposed to do with this personality now? How does it shine through? How does it help us make more money? Why are we doing this? These are all great questions. Having a clear brand personality will make so many decisions easier that you will regret you hadn’t defined one before. For example:

Wouldn’t it be easier to know whom to partner with once you know how your brand feels about life in general?

Wouldn’t it be that much simpler to choose a social media message once you know how your brand is supposed to sound?

Defining our brand personality gives us a better idea of how we should face the customer. It elucidates what is the voice telling the story. Keep this idea of brand voice close to heart; based on the personality we just described:

What would my brand say and how? Along the same lines, how would my brand speak to customers during the different stages of their experience? More on this in the upcoming Product section.

What does it hate?

What does it absolutely love?

What is its favorite drink or meal? Why?

(We could go on forever, now that we have a personality.)

Consider the following example of a brand personality and how it translates into the brand’s voice.

Coming up next, you will see how this personality comes into play in different stages of interaction with your customer. Time to speak up!

Product: What Will You Offer over Time?

Strong brands know that there’s much more to it than “the sell.” The term product experience does a better job at capturing what it is that our brand is really standing for. We’re used to thinking that products (and services) are just a sum of features, but taking a closer look at the customer’s experience reveals the truth: products are an augmented set of opportunities to add value that includes (of course) tangible features, but also service, visual identity, support, warranties, delivery, installation...the stuff people pay a premium for. The stuff strong brands are made of.

Products shouldn’t just work well, they must unfold well.

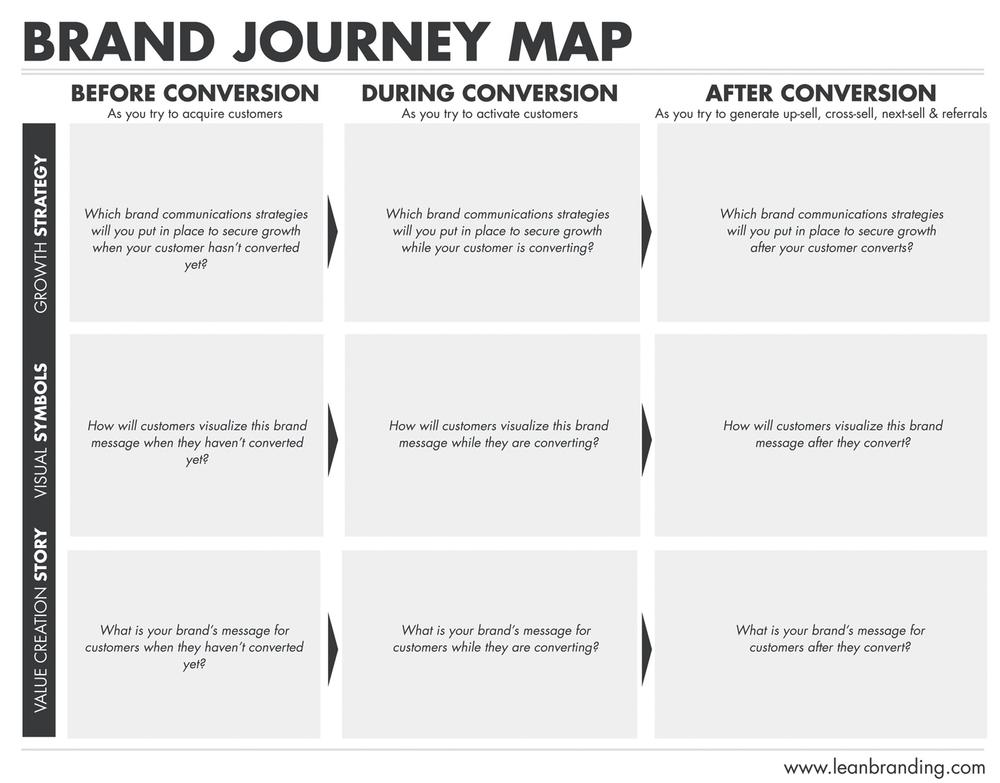

Using Journey Maps to design your product experience

A useful way to visualize your product experience is to use a Customer Journey Map. These maps display the complete adventure that customers jump on the minute they consume your product. It is important to remember that consumption involves pre-purchase, purchase, and post-purchase stages, and consumers will be looking for you all along. A complete Journey Map includes these three stages. The main idea here is that customers are not just looking for value on the spot. These stages are all brand touchpoints in which you can add value, and it is essential to recognize what and where they are and how you’ll respond to consumers during each of them. Think about a few stages that your own customer would go through as he consumes your product:

- Before purchase

Maybe he has to check out a few other options before deciding whether to purchase your brand. What will you do during this stage to make sure that he learns about you? If this is a corporate purchase, does the buyer need someone else’s approval? If it isn’t, will he need his wife’s approval?[29] Once he learns about you, how will you communicate what makes you different (and worthy of his decision)? (Chapter 5 will discuss communication strategies in depth.)

- During purchase

The customer actually pays for your product. Is there something you can say or do to make this process easier or more rewarding? Is there a stimulus that you can provide to make the decision-making process simpler?

- After purchase

How does your product interact with the customer after he has purchased it? How does it resolve his initial aspirations? Perhaps your product involves an installation process. Even if it doesn’t, consumers want to be able to communicate with you after their purchase and reaffirm that their choice was correct (read the upcoming “Dig Deeper” box to learn more). How will you make the customer feel that his purchase decision was right? If this is a corporate purchase, will other departments resent your customer’s decision? May coworkers dislike the fact that your customer’s purchase changed their workflow? What can you say or do to make sure that your product’s integration with the customer’s routine is seamless?

Back in Chapter 1 we discussed the importance of understanding that brand and product don’t compete. Brand is product, and everything else conforming to the unique story that consumers create when they think of you. Therefore, we can now think of your product experience in terms of all the brand elements that must come together when someone consumes your offer. To make this easier for you, the following Brand Journey Map template includes a series of stages and boxes to fill out as you design the experience that you are trying to offer.

Mapping the brand journey makes visualizing this process easier. I urge you to take a few minutes to draw your own path to identify where and how your brand story will be told.

In each step, try to picture what aspect of your brand experience is interacting with your customer. I understand this might be a little abstract, but check out the next “Inspiration Hack” sidebar to find a few examples of journey steps that would work for a web-based solution.

Pricing: How Much Is Your Solution Worth?

At this point, you’ve created a brand promise and positioning, defined buyer personas, and mapped an engaging product journey infused with an equally appealing brand personality. Good job! Now it’s time to reap the rewards.

But just how will you go about figuring out what this reward should be? How will you fix a price that appeals to your buyers and keeps your company’s finances healthy? When is it too much and when are you underestimating what your solution is worth to the buyer?

We could spend days discussing pricing strategies from multiple standpoints. There are at least a dozen different pricing models that you can consider putting in place, but we will look at three of the most widely used:

- Cost-based pricing

You set a price based on production cost considerations and profit objectives. Every company gauges these production costs differently, but an essential question remains: How much should we charge for this product or service if it costs us X to produce and we want to earn Y on top of that?

- Value-based pricing

You set a price based on the customer’s perception. During this pricing process, you basically figure out how much value your customer places on the product or service that your brand offers. How much is she willing to pay for this product?

- Competition-based pricing

You set a price for your product or service based on your closest competitors’ strategies. When you have little or no competition (in a disruptive category), you can look at substitute products. How much is my closest competitor charging for a similar product or service? Do I want my price to be at, above, or below theirs?

More often than not, a brand’s pricing strategy is a combination of two or more of the models just presented. For example, a company like Samsung may concurrently consider production costs, its target customers’ willingness to pay, and other manufacturers’ strategies when deciding on a price for its products. Other widely used pricing strategies include:

- Penetration pricing

Setting a low price to grab a large share of the market when you are launching.

- Skimming or “creaming” price strategy

Setting up a high price initially to recover what you have invested in developing the product.

- Freemium

Offering one version of your product or service for free and a more advanced version for a fee.

- Premium pricing

Setting up a deliberately high price because it allows your brand to appeal to a specific market segment with a certain purchasing power.

- Psychological pricing

Setting a price having considered how the actual numbers play a role in a consumer’s decision-making process. For example, you may validate that charging $4.99 instead of $5.00 helps boost sales. This tactic relies on the idea that customers will (involuntarily) round down and perceive a lower price, which in turn triggers a purchase.

If you decide to use value-based pricing, keep in mind your potential buyer’s answer to these questions from our Personas section (earlier in this chapter):

Purchase criteria and motivations: What makes him complete the purchase of an existing solution, similar to the one your brand proposes? How much is he willing to pay?

In Chapter 7, when we measure our brand story ingredients, you will learn about a pricing concept called willingness to pay. This indicator will allow us to approximate our buyers’ ideal price point(s) and approach our brand’s pricing from a value-based perspective.

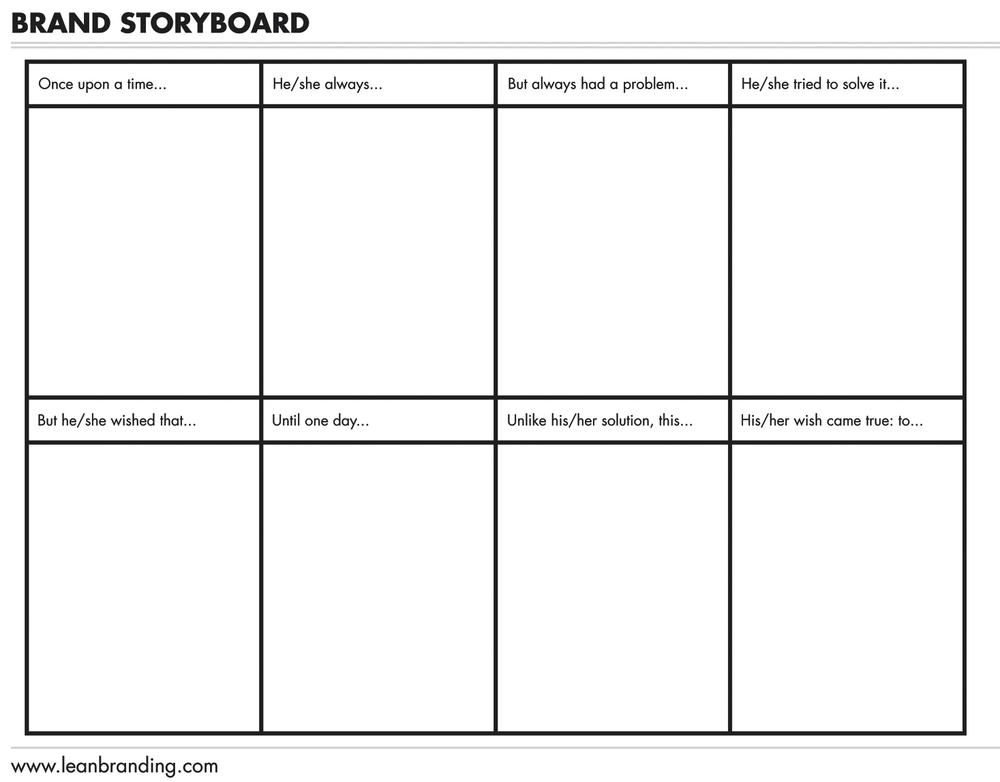

Bringing It All Together: Your Brand Storyboard

At this point, you have built a positioning, promise, personas, personality, product experience, and pricing for your brand. As we approach the next steps in this process, it helps to continuously visualize your entire brand story.

While I worked with tech startup teams from every background imaginable, I noticed that storytelling doesn’t come easy for many of us. That’s why I designed this simple tool:

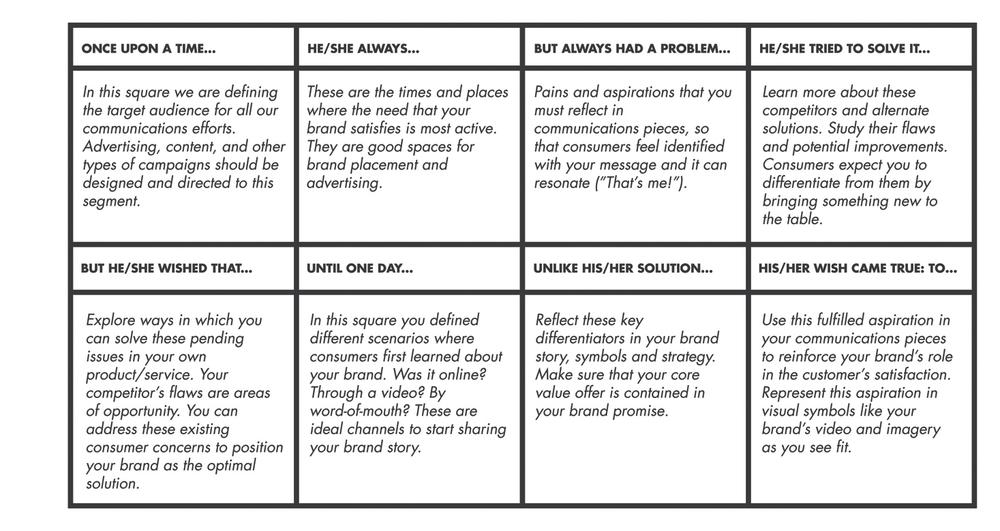

By completing each of these scenes, you will be answering some of the key questions behind powerful brand storytelling. Let’s go over some considerations as you fill out the storyboard:

- Once upon a time

In this scene, you will describe the buyer personas introduced earlier in this chapter using images or text. Who is the main character in your brand story?

- He/she always

Define some of the main tasks that your customer is regularly involved with. What does she do every day? What are her main responsibilities in life and work, as related to the product or service that you offer?

- But always had a problem

State the main issue that your customer faces when trying to complete her tasks. What is the unsatisfied need or aspiration in this story?

- He/she tried to solve it

If the previous problem is real, your customer is probably already solving it. What are some alternate solutions to the issue at hand? How is your customer managing to partially satisfy this aspiration?

- But he/she wished that

Outline the flaws in the solutions your customer is currently using. Despite purchasing these other products or services, your customer is still unsatisfied. What are existing solutions lacking?

- Until one day

Describe how your customer will most probably learn about your brand. What happened on the day she first heard about you?

- Unlike his/her solution, this

List some of the aspects related to your product experience that set you apart from competitors. How does your offer differ from your customer’s current solution?

- His/her wish came true, to

Clearly define the aspiration that your brand fulfills. What is your customer’s “wish come true”?

Now that you have filled out each of these scenes, consider some of the implications of each of your answers. Why do they matter? How can we use them? Why are they important for brand building and conversion? The following storyboard provides some thoughts:

Recap

As you’ll remember from Chapter 1, we are in the business of taking customers from A to B, where A is their position today and B is the place they want to be tomorrow. Building a dynamic brand story helps drive this message home for the consumer. While digital communication channels are important, they are just tools to show (what should be) a meaningful brand story.

Many different ingredients are involved in creating your brand story. In this chapter, we introduced six of them: your positioning, promise, personas, personality, product experience, and pricing. A brand’s positioning conveys which space you are trying to occupy, the main aspiration that you are trying to satisfy, and an idea of who else is competing for that space. Your brand promise is basically a fun-sized version of your positioning statement, emphasizing on your core value offer. It should answer the question, “What’s in it for me?”

Personas are “fake” people with very real needs or aspirations that inspire everything our brand is, does, and communicates. By crafting our brand messages around these personas, our story will become more humane. This is important because people relate to people, and if your brand feels like “people,” they’ll relate to you, too.

Strong brand stories satisfy consumer aspirations with a well-designed, holistic product experience. Products shouldn’t just work well, they must unfold well. Finally, defining our brand personality gives us a better idea of how we should face the customer. It elucidates the voice telling the story.

[24] It is important to make this distinction because, as you’ve learned before, customers cocreate this positioning with you once your brand is out in the marketplace.

[25] Bob coauthored The Startup Owner’s Manual (K & S Ranch) with Steve Blank. A serial entrepreneur, he has founded seven startups for two home runs, two basehits, and three tax losses. He has invested in or advised more than a score of startups and teaches customer development at Columbia Business School.

[27] Bruce Hanington and Bella Martin, Universal Methods of Design: 100 Ways to Research Complex Problems, Develop Innovative Ideas, and Design Effective Solutions (Beverly, MA: Rockport Publishers, 2012).

[28] Richard J. Gerrig and Philip G. Zimbardo, Psychology and Life, 16th edition (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2002).

[29] These people standing between you and the buyer, affecting the buyer’s decision, are known as gatekeepers.